Back to Journals » International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease » Volume 12

Improving adherence to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency screening guidelines using the pulmonary function laboratory

Authors Luna Diaz LV, Iupe I , Zavala B, Balestrini KC , Guerrero A, Holt G, Calderon-Candelario R , Mirsaeidi M , Campos M

Received 7 June 2017

Accepted for publication 5 July 2017

Published 31 July 2017 Volume 2017:12 Pages 2257—2259

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S143424

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Russell

Landy V Luna Diaz,1 Isabella Iupe,1 Bruno Zavala,1 Kira C Balestrini,1 Andrea Guerrero,1 Gregory Holt,1,2 Rafael Calderon-Candelario,1,2 Mehdi Mirsaeidi,1,2 Michael Campos1,2

1Miami Veterans Administration Medical Center, Miami, FL, 2Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, University of Miami School of Medicine, Miami, FL, USA

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) is the only well-recognized genetic disorder associated with an increased risk of emphysema and COPD.1 Identifying AATD allows genetic counseling and the chance to offer specific augmentation therapy to slow emphysema progression. Despite specific recommendations from the World Health Organization, American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society to screen all patients with COPD and other at-risk conditions,2–4 testing rates are low (<15%).5

We conducted a project to improve AATD screening at the Miami VA Medical Center using the pulmonary function test (PFT) laboratory. We instructed the PFT personnel to perform reflex testing on all patients with pre-bronchodilator airflow obstruction (forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity <70%) and then evaluated if the screening was appropriate according to guidelines. Trained PFT personnel explained AATD disease to patients and provided them with an informational brochure. After obtaining verbal consent, AATD screening was performed using dried blood spot kits provided by the Alpha-1 Foundation as part of the Florida Screening Program (noncommercial).6 The PFT lab director was the responsible physician of record, in charge of discussing positive results to patients and documenting results in the electronic medical record. The Miami Veterans Affairs Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved the protocol as a quality improvement project.

Dear editor

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) is the only well-recognized genetic disorder associated with an increased risk of emphysema and COPD.1 Identifying AATD allows genetic counseling and the chance to offer specific augmentation therapy to slow emphysema progression. Despite specific recommendations from the World Health Organization, American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society to screen all patients with COPD and other at-risk conditions,2–4 testing rates are low (<15%).5

We conducted a project to improve AATD screening at the Miami VA Medical Center using the pulmonary function test (PFT) laboratory. We instructed the PFT personnel to perform reflex testing on all patients with pre-bronchodilator airflow obstruction (forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity <70%) and then evaluated if the screening was appropriate according to guidelines. Trained PFT personnel explained AATD disease to patients and provided them with an informational brochure. After obtaining verbal consent, AATD screening was performed using dried blood spot kits provided by the Alpha-1 Foundation as part of the Florida Screening Program (noncommercial).6 The PFT lab director was the responsible physician of record, in charge of discussing positive results to patients and documenting results in the electronic medical record. The Miami Veterans Affairs Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved the protocol as a quality improvement project.

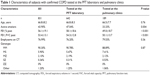

Since launching the program, testing rates in our center had a 15-fold increase from baseline. In 4 years, the PFT laboratory performed 78% of the 1,021 tests ordered in our institution, leading to a decrease in the number of tests done by the pulmonary clinic (Figure 1). Review of the 799 cases tested by the PFT laboratory found that 671 (83%) had an appropriate clinical indication for screening according to guidelines.3,4 The remaining subjects tested had mostly asthma (9.6%), other reasons for airflow obstruction such as sarcoidosis (2.2%) or did not have airflow obstruction (5%). Importantly, the COPD patients tested by the PFT laboratory were more likely to be active smokers with significantly better lung function compared with those tested at the pulmonary clinic (Table 1).

Our experience highlights the importance of partnering with PFT laboratory personnel to improve AATD testing rates. Respiratory therapists are exposed to a higher number of pulmonary patients at risk for AATD than pulmonologists and can improve detection of affected individuals in the course of their routine practices.7 Continued education efforts and focusing on testing subjects with persistent airflow obstruction after bronchodilator testing could further reduce unnecessary testing rates. We conclude that reflex AATD testing by PFT personnel is an effective way to comprehensively and appropriately test subjects at risk. Furthermore, this strategy appears to identify a population that is more amenable to benefit from detection at an earlier disease stage.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Stoller JK, Aboussouan LS. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Lancet. 2005;365(9478):2225–2236. | ||

[No authors listed] Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency: memorandum from a WHO meeting. Bull World Health Organ. 1997;75(5):397–415. | ||

American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: standards for the diagnosis and management of individuals with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(7):818–900. | ||

Sandhaus RA, Turino G, Brantly ML, et al. The diagnosis and management of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency in the adult. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis (Miami). 2016;3(3):668–682. | ||

Stoller JK, Brantly M. The challenge of detecting alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. COPD. 2013;10 (Suppl 1):26–34. | ||

Gorrini M, Ferrarotti I, Lupi A, et al. Validation of a rapid, simple method to measure alpha1-antitrypsin in human dried blood spots. Clin Chem. 2006;52(5):899–901. | ||

Stoller JK, Strange C, Schwarz L, Kallstrom TJ, Chatburn RL. Detection of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency by respiratory therapists: experience with an educational program. Respir Care. 2014;59(5):667–672. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.