Back to Journals » International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease » Volume 10 » Issue 1

Important, misunderstood, and challenging: a qualitative study of nurses’ and allied health professionals’ perceptions of implementing self-management for patients with COPD

Authors Young H , Apps L, Harrison S, Johnson-Warrington V, Hudson N, Singh S

Received 3 December 2014

Accepted for publication 23 February 2015

Published 3 June 2015 Volume 2015:10(1) Pages 1043—1052

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S78670

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Russell

Hannah ML Young,1 Lindsay D Apps,1 Samantha L Harrison,1 Vicki L Johnson-Warrington,1 Nicky Hudson,2 Sally J Singh1,3

1National Institute of Health Research CLAHRC-LNR Pulmonary Rehabilitation Research Group, University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, 2School of Applied Social Sciences, De Montfort University, Leicester, 3Applied Research Centre in Health and Lifestyle Interventions, Coventry University, Coventry, UK

Background: In light of the growing burden of COPD, there is increasing focus on the role of self-management for this population. Currently, self-management varies widely. Little is known either about nurses’ and allied health professionals’ (AHPs’) understanding and provision of self-management in clinical practice. This study explores nurses’ and AHPs’ understanding and implementation of supported COPD self-management within routine clinical practice.

Materials and methods: Nurses and AHPs participated in face-to-face semistructured interviews to explore their understanding and provision of COPD self-management, as well as their perceptions of the challenges to providing such care. Purposive sampling was used to select participants from a range of professions working within primary, community, and secondary care settings. Three researchers independently analyzed each transcript using a thematic approach.

Results: A total of 14 participants were interviewed. Nurses and AHPs viewed self-management as an important aspect of COPD care, but often misunderstood what it involved, leading to variation in practice. A number of challenges to supporting self-management were identified, which related to lack of time, lack of insight regarding training needs, and assumptions regarding patients’ perceived self-management abilities.

Conclusion: Nurses and AHPs delivering self-management require clear guidance, training in the use of effective self-management skills, and education that challenges their preconceptions regarding patients. The design of health care services also needs to consider the practical barriers to COPD self-management support for the implementation of such interventions to be successful.

Keywords: self-management, COPD, qualitative, interviews, nurses, allied health professionals

Introduction

Background

COPD is a global health issue and the fourth-leading cause of death worldwide, with morbidity and mortality predicted to rise in coming years.1–4 COPD exacerbations can result in increased health care utilization and significant burden to the individual.4–6 Self-management has been defined as the systematic provision of supportive interventions designed to increase patients’ skills in decision making, problem solving, utilizing resources, and taking action.1,7–10 Self-management is an integral part of good practice models in chronic disease management, as it seeks to enhance patient confidence, health, and well-being while reducing health care utilization.11–18 In light of the growing burden of COPD, there is increasing focus on the role of self-management within this population, enhanced by a growing body of evidence advocating its benefits; however, the precise format and structure of self-management is inconsistent.4,6,19–23

Heterogeneity exists between COPD self-management interventions, and there is a lack of guidance on what components form essential prerequisites. This may create confusion for patients, nurses, and allied health professionals (AHPs), and consequently some self-management studies report little impact or negative outcomes.1,5,24–26,27 The delivery of self-management requires a skilled and knowledgeable practitioner to best enable collaborative working and the acquisition of skills by the patient.28,29 Confidence in this practitioner has been shown to be important in COPD care, but there has been little focus on the role of the nurses and AHPs in the implementation of self-management for COPD.28

Challenges to self-management

The chronic care model highlights that self-management implementation requires investment in professional development, yet there is a lack of specialist training and education available specifically for COPD.9,11,30 This absence leaves self-management support very dependent upon nurses’ and AHPs’ existing perceptions and knowledge.31 Although these perceptions have been described across other chronic disease groups, to our knowledge only one small survey study has been conducted with nurses working with COPD patients.7–9,14,16,28–30,32–36 This study highlights a wide variety of definitions of self-management, as well as a number of limitations to self-management delivery.36 No in-depth qualitative studies have specifically explored nurses’ and AHPs’ understanding of self-management for COPD or their perceptions of the challenges to providing such care. Given that COPD follows an uncertain disease trajectory, and that patients can feel guilty about the often self-inflicted nature of the disease and embarrassed about symptoms, such a study is particularly timely.28,29,37–39

The purpose of this study was to explore nurses’ and AHPs’ understanding of self-management for COPD, as well as their perceptions of the challenges to providing such care. Understanding these views is an important step toward enhancing COPD self-management implementation and training.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval and consent

The study was approved by the Local Research Ethics Committee, University Hospitals of Leicester Research and Development Department, Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland Primary Care Research Alliance, and the West Midlands South Comprehensive Local Research Network (07/H0408/114). All participants gave written informed consent.

A qualitative methodology utilizing a phenomenological approach was employed, as the aim of this study was to explore the lived experience of nurses’ and AHPs’ supporting COPD self-management and their perceptions of the challenges to providing such care.

Design and setting

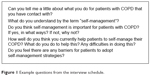

Face-to-face semistructured interviews lasting 35–90 minutes were used to explore participants’ views in depth. The interview schedule included open-ended questions and probes, the development of which was informed by a thorough literature review and the research team’s experience of supporting self-management. Example interview questions are included in Figure 1. Initial interviews acted as pilots. Interviews were conducted in a private setting within the participants’ workplace by a research physiotherapist (VLJW) who was unknown to the participants, to allow them to speak freely.

| Figure 1 Example questions from the interview schedule. |

Sample

A convenience sample of nurses and AHPs (physiotherapists and an occupational therapist) from primary, community, and secondary care settings were recruited via National Health Service (NHS) primary care trust websites, poster advertisements, and mail-outs to practice managers. These participants were all currently or recently (within the last year) working with COPD patients, and might reasonably have been supporting them with self-management as part of their role. Neither primary nor secondary care physicians were included in the study sample, because they are unlikely to deliver structured self-management interventions in a UK health care setting.

From a pool of interested nurses and AHPs, purposeful nonprobability sampling was utilized to select participants with a wide diversity of views, using a variety of different criteria (Table 1). Sampling occurred until data saturation was achieved, ie, no new insights or information were gathered.40

| Table 1 Participant characteristics (n=14) |

Data analysis

All data were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. Field notes were also subject to analysis. NVivo software (version 9; QSR International, Doncaster, VIC, Australia) was used to manage all data.

Thematic analysis was selected as the means of data analysis, because it allows for the systematic organization of data and enables explicit and implicit constructs within the participants’ accounts to be linked into comprehensive a account that encapsulates participants’ experiences. This is of particular relevance to qualitative work that may help to inform policy and practice development.41

Three researchers who were AHPs with extensive experience in self-management, COPD, and qualitative research (HMLY, SLH, and LDA) independently familiarized themselves with the data and generated initial codes inductively from the data and identified themes.41 These themes were reviewed and defined collectively by the whole research team, who moved back and forth between stages as new themes emerged and relationships were recognized.41 Reliability was ensured through continuous discussion about the data with the wider multidisciplinary research team. Consensus meetings were utilized to ensure agreement over emergent themes.

Results

A total of 35 nurses and AHPs received information regarding the study. Fourteen agreed to participate, from a group of 18 who initially expressed interest. Of the four who did not take part, two were unable to attend and two were not eligible for the study. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. None of the participants had undertaken specific self-management training with respect to COPD.

Emergent themes

Analysis of the data resulted in two larger themes representing nurses’ and AHPs’ understanding and delivery of self-management and perceived challenges to supporting self-management. These are described further with relevant subthemes: 1) understanding and delivery of self-management (education, behavior change, collaboration, other skills), and 2) challenges and barriers to self-management (time, experience, patients).

Nurses and allied health professionals’ understanding and delivery of supported self-management: misunderstood and variable

All nurses and AHPs recognized the importance of self-management in the care of their patients, as it primarily allowed them to utilize their limited time effectively. Despite this, it was clear that there were misunderstandings regarding self-management, and participants gave a wide spectrum of different definitions.

Many participants spoke of referral to pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) when asked about the self-management support that they provided to COPD patients. Participants described how supporting self-management was not always integral to their daily practice, and thus referral to PR became an alternative. See Table 2 for example quotations. Two practice nurses expressed deep frustration at not being able to directly address patients’ self-management needs, while others had actively taken steps to allow them to assist with supporting self-management within the constraints of their role.

Education

Perceptions of the delivery of self-management in practice also varied. All nurses and AHPs considered education to be a key element, and felt that their patient’s knowledge was directly related to accurate symptom interpretation and speedier engagement with health care services. Education was delivered to patients verbally, and aimed primarily to encourage compliance, particularly in relation to medications and exacerbation management. See Table 3 for example quotations.

| Table 3 Exemplar quotations from interviews regarding how nurses and AHPs currently support self-management within their daily practice |

Behavior change

Nurses and AHPs described feeling powerless to address the behavior change they viewed as another key part of self-management. Some participants assumed that increased knowledge via the provision of facts and information would automatically encourage health-behavior change. Participants felt that it was difficult to assess a patient’s readiness to change. Most were hesitant about approaching patients they viewed as resistant or ambivalent. They struggled to identify management strategies for these patients and to assess whether these were effective. Only one professional was using motivational interviewing, a patient-centered counseling approach to enhance motivation to change and explore ambivalence.42,43 See Table 3 for example quotations.

Collaboration

Three participants described working collaboratively with their patients, which was primarily achieved by developing a rapport. They believed this rapport encouraged honesty and helped the professional to tailor their support. Despite this, the majority of the nurses and AHPs still set the agenda for their consultations, provided patients with solutions to their problems (as perceived by the professional), and “gave” them self-management skills. See Table 3 for example quotations.

Other self-management skills

To a much lesser extent, participants described using other self-management techniques in practice. Goal setting was considered valuable in helping motivate and encourage patients, yet nurses in particular were unfamiliar with structured goal setting. Only three participants felt it important to help patients access and utilize other health care resources. Action planning for acute exacerbation was similarly underutilized, although participants were aware of the potential benefits of these plans. See Table 3 for example quotations.

Challenges and barriers to supported self-management

Time

The greatest perceived challenge to the provision of self-management support to COPD patients in practice was lack of time, exacerbated by the need to prioritize other tasks. Other activities, particularly achieving the Quality and Outcomes Framework indicators, were often prioritized. See Table 4 for example quotations.

Experience

Eleven participants felt that their professional knowledge alone ensured the skills and competence to support COPD patients to self-manage. Consequently, the majority of nurses and AHPs, when this was explored further, were often not consciously aware of any personal learning needs regarding self-management, although the learning needs of more junior staff were identified.

Despite this, three participants identified that greater experience and levels of specialism may create difficulties communicating with patients, and sharing “control” with patients. Another participant outlined some of the self-management advice that she had picked up through her practice, which highlights a lack of standardization in the self-management support and education provided to patients. This has the potential to lead to inconsistent messages provided to patients across health care settings. See Table 4 for example quotations.

Patients

The provision of self-management support in practice was further influenced by participants’ assumptions about a patient’s ability to self-manage. Older patients were seen as less confident, unmotivated, and having greater potential for cognitive deficits that could impede self-management. Five participants also felt that older patients preferred to defer responsibility for managing their condition to the professional, as well as enjoying the social interaction offered by regular visits to health care services. Older COPD patients were viewed as less likely to regard their symptoms as deviant from the normal aging process, and thus less likely to engage in activities aimed at addressing them.

Self-management was also believed to be culturally less acceptable to patients from ethnic minority backgrounds, and yet participants did not specify what these barriers might entail. Practical issues, such as language barriers, also made collaboration and education more difficult. These assumptions appeared to influence the amount and type of support that these groups of patients were given. See Table 4 for example quotations.

Discussion

Main findings

This study is the first to examine nurses’ and AHPs’ perceptions of self-management specifically in relation to COPD, and our findings have important implications for both the implementation of self-management within clinical practice and professional education. Although very mixed views about self-management existed, in general it was seen as an important way to utilize limited resources efficiently while empowering patients. There was explicit lack of coherence about how to support self-management, which created variation in practice. There are also a number of practical barriers and professional assumptions that appear to influence self-management implementation negatively.

Self-management is shrouded in confusion for professionals working in clinical practice, and the term is often rather curiously used synonymously with PR. This variation is perhaps unsurprising, given that research designed to evaluate self-management has shown large variation in content, follow-up, and outcome measures used. PR includes patient education, psychological support, and behavior modification designed to enhance self-management, but is distinct in that it also provides opportunities for social interaction and supervised exercise.24 PR is often only offered at the latter stages of COPD, can be resource- and time-intensive, and may not be appropriate or readily available for many patients.14,24

Limitations

Although the interviews provided a great deal of rich data, the study was not without its limitations. The sample of nurses and AHPs recruited for the study were all female, predominantly of white British background. While the sex and ethnicity bias reflects the general trends within the UK health service workforce, we cannot be certain whether the viewpoints of participants in this study would be shared by male participants and those from other ethnic backgrounds. We did not confirm whether participants had in fact received formal training for self-management in any other long-term condition. Interestingly, this was not identified by any participants, suggesting that no relevant training that may have influenced their knowledge and skills in relation to COPD self-management had been received.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previous work

This study demonstrates that increasing patient knowledge was viewed by participants as a key element of self-management, sufficient to ensure behavior change, while other elements were marginalized, due to lack of time, awareness, and professional confidence. Nurses and AHPs have difficulty detaching themselves from traditional health education models that encourage them to provide information based on their interpretation of the impact of the disease for the patient.30,32,35,44–47

Delivered alone, such education has little impact upon patient behavior across a spectrum of chronic diseases, including COPD, as it fails to consider patients’ self-efficacy and the importance they place upon behavior change.1,3,18,20,28,29,36,46–48 Self-management support requires nurses and AHPs to regard their expertise as complementary to that of the patients in managing their disease within the context of their life.4,7,8,10,14,16,24,28,42,43,49–52 Despite this, our study and others highlight that nurses and AHPs often facilitate collaboration solely through the development of a good rapport with the patient.18 The resultant partnership work is often superficial, as many of the professionals still sought to lead consultations and viewed patients’ failure to comply with their advice as evidence of the individuals’ inability to self-manage. These assumptions may block patients’ attempts to become more autonomous, perpetuating passivity.13–17,32,33,44,50

This study highlights the fact that the nurses and AHPs base their current self-management practices upon knowledge and skills developed through practice and experience rather than formal training, and that most are not aware of any education needs. This is supported by a study evaluating a self-management training program that concluded that many professionals felt they already possessed the necessary skills and knowledge to deliver self-management support.35 This represents a significant barrier to the delivery of training to nurses and AHPs, as professional experience alone has been found to be insufficient preparation to deliver self-management in other chronic diseases and leads to the selective use of strategies that may be ineffective or inappropriate.16,18,31,33,52 Structured training forms a standard part of the delivery of some self-management interventions in other long-term conditions (eg, the DESMOND [Diabetes Education and Self Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed] program for diabetes), and a similar approach appears warranted in COPD care.

Previous qualitative literature has demonstrated how nurses and AHPs use judgments about patients to predict their likely behavior and thus guide patient interactions and care.53–55 More recent studies have also shown that judgments are also made in relation to patient’s ability to self-manage, although this has not previously been demonstrated in COPD.47 Our work indicates that these extend to the belief that older and ethnic minority patients are less able to undertake self-management.31,35,45 The assumptions made by nurses and AHPs about what care is appropriate for them may prevent this patient group from receiving appropriate and tailored support.4,10,47 Self-management training must additionally address these issues.

A recent Cochrane review indicates clear benefit of self-management interventions, and thus should be internationally endorsed. The trials are heterogeneous, and range from a complex supervised intervention over several months to far-briefer interventions.1 The training of the staff supporting these interventions is rarely described. A rigorous international effort to define the competence of staff to deliver effective self-management may be required. A recent self-management trial was terminated prematurely, because of concerns over a detrimental effect of the intervention; the reasons behind the excess mortality in the intervention group are unclear, the data suggested the intervention had not altered the behaviors of the group, and one might argue that more staff training might be required firstly to identify those participants that might be successful self-managers, as intimated by the study by Bucknall et al.26

Time limitations and the prioritization of other duties are also barriers that frustrate nurses and AHPs trying to support self-management. Similar challenges have been highlighted in other self-management studies, and include practical constraints, such as inflexible health care infrastructures, excessive workload, and lack of privacy and continuity of care.2,13,30,35,36,44,45,51,56 These barriers appear to encourage nurses and AHPs to enforce compliance, make decisions for patients, and offer solutions to their problems, reducing the effectiveness of self-management support. These barriers need to be carefully considered in the design of services and interventions if self-management implementation is to be effective.17

Implications for future research, policy, and practice

As the burden of chronic disease grows, the importance of supported self-management is consistently acknowledged, yet the workforce seems ill-prepared to support patients with COPD. There is a need to develop guidance that clarifies how it should be delivered, together with the professional competence and quality-assurance standards that have driven up the quality of self-management support in other chronic diseases, such as diabetes.18,52 The requirements to support individuals with COPD to self-manage their disease effectively is irrespective of the mode of delivery. A number of different approaches and technologies have been tested to support self-management in COPD, with disappointing results.26,57,58 We may speculate that more training is required for the health care practitioner and the individual with COPD to manage the burden of the disease effectively and achieve important lifestyle changes.

Our work also suggests that as well as guidance and training in self-management skills, nurses and AHPs may also benefit from education that challenges the assumptions they may make about patients’ abilities to self-manage, and future research should focus upon developing and testing such educational programs.

Conclusion

Self-management is valued by nurses and AHPs and believed to be important, yet there is misunderstanding about what it entails. There were also practical challenges and professional assumptions made about the ability of COPD patients to self-manage, all of which led to further variation in support.

Nurses and AHPs were ill-equipped to support self-management, and there was wide variation described in the self-management support for COPD patients in daily practice. These problems may be addressed by clearer guidance for the implementation of self-management in COPD and professional training that addresses both nurses’ and AHPs’ skills and challenges their attitudes. Careful thought also needs to be given to the design of existing services so that more time is allowed to accommodate self-management for COPD within primary care where multiple conflicting priorities may exist.

Acknowledgments

This research was jointly supported by a research grant from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), through its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme and the Collaboration for Leadership in Health Research and Care East Midlands (CLAHRC EM). This paper presents independent research funded by the NIHR and supported by the CLAHRC EM. The views expressed are those of the author(s), and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Author contributions

HMLY carried out the data analysis and data interpretation. SLH and LDA carried out the data analysis and assisted with data interpretation. VLJW conducted the data collection. NH and SJS designed the study and assisted with data interpretation. SJS conceived of the study. All authors assisted in drafting, revising and approving the final manuscript. All authors accept accountability for all aspects of the final manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Effing T, Monninkhof EE, Van der Valk P, et al. Self-management education for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD002990. | ||

Selecky CE. Disease management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from a disease management organization perspective. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2008;16(5):319–325. | ||

Wortz K, Cade A, Menard JR, et al. A qualitative study of patients’ goals and expectations for self-management of COPD. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;21(4):384–391. | ||

Department of Health. An Outcomes Strategy for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Asthma in England. London: Department of Health; 2011. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216139/dh_128428.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2015. | ||

Fan VS, Gaziano JM, Lew R, et al. A comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(10):673–683. | ||

Rice KL, Dewan N, Bloomfield HE, et al. Disease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(7):890–896. | ||

Lorig KR, Homan H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1–7. | ||

Lorig KR. Self-management education: more than a nice extra. Med Care. 2003;41(6):699–701. | ||

Kielmann T, Huby Powell A, et al. From support to boundary: a qualitative study of the border between self-care and professional care. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(1):55–61. | ||

Bourbeau J, Nault D, Dang-Tan T. Self-management and behaviour modification in COPD. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52(3):271–277. | ||

Lewis R, Dixon J. Rethinking management of chronic diseases. BMJ. 2004;328(7433):220–222. | ||

Department of Health. The Expert Patients Programme. 2007. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Aboutus/MinistersandDepartmentLeaders/ChiefMedicalOfficer/ProgressOnPolicy/ProgressBrowsableDocument/DH_4102757. Accessed April 21, 2015. | ||

Blakeman T, Macdonald W, Bower P, Gately G, Chew-Graham C. A qualitative study of GPs’ attitudes to self-management of chronic disease. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(527):407–414. | ||

Redman BK. The ethics of self-management preparation for chronic illness. Nurs Ethics. 2005;12(4):360–369. | ||

Catalano T, Kendall E, Vandenburg A, Hunter B. The experiences of leaders of self-management courses in Queensland: exploring health professional and peer leaders’ perceptions of working together. Health Soc Care Community. 2009;17(2):105–115. | ||

Astin F, Closs SJ. Chronic disease management and self-care support for people living with long-term conditions: is the nursing workforce prepared? J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(7B):105–106. | ||

Kennedy A, Rogers A, Bowler P. Support for self care for patients with chronic disease. BMJ. 2007;335(7627):968–970. | ||

Partridge MR, Hill SR. Enhancing care for people with asthma: the role of communication, education, training and self-management. Eur Respir J. 2000;16(2):333–348. | ||

Adams R, Chavannes N, Jones K, Ostergaard MS, Price D. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a patients’ perspective. Prim Care Respir J. 2010;15(2):102–109. | ||

Bourbeau J, Julien M, Maltais F, et al. Reduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a disease-specific self-management intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(5):585–591. | ||

Effing T, Zielhuis G, Kerstjens H, van der Valk P, van der Palen J. Community based physiotherapeutic exercise in COPD self-management: a randomised controlled trial. Respir Med. 2011;105(3):418–426. | ||

Chavannes NH, Grijsen M, van der Akker M, et al. Integrated disease management improves one-year quality of life in primary care COPD patients: a controlled clinical trial. Prim Care Respir J. 2009;18(3):171–176. | ||

Khdour MR, Kidney JC, Smyth BM, McElnay JC. Clinical pharmacy-led disease and medicine management programme for patients with COPD. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68(4):588–598. | ||

Wagg K. Unravelling self-management for COPD: what next? Chron Respir Dis. 2012;9(1):5–7. | ||

Monninkhof E, van der Valk P, van der Palen J, van Herwaarden C, Zielhuis G. Effects of a comprehensive self-management programme in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(5):815–820. | ||

Bucknall CE, Miller G, Lloyd SM, et al. Glasgow supported self-management trial (GSuST) for patients with moderate to severe COPD: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e1060. | ||

Harrison SL, Janaudis-Ferreira T, Brooks D, Desveaux L, Goldstein RS. Self-management following an acute exacerbation of COPD: a systematic review. Chest. 2015;147(3):646–661. | ||

George J, Kong DC, Santamaria NM, Ioannides-Demos LL, Stewart K. Adherence to disease management interventions for COPD patients: patients’ perspectives. J Pharm Pract Res. 2006;36(4):278–285. | ||

Cornforth A. COPD self-management supportive care: chaos and complexity theory. Br J Nurs. 2013;22(19):1101–1104. | ||

Robertson S, Witty K, Braybrook D, Lowcock D, South J, White A. ‘It’s coming at things from a very different standpoint’: evaluating the ‘Supporting Self-Care in General Practice Programme’ in NHS East of England. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2013;14(2):113–125. | ||

Lake AJ, Staiger PK. Seeking the views of health professionals on translating chronic disease self-management models into practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(1):62–68. | ||

Costantini L. Compliance, adherence, and self-management: is a paradigm shift possible for chronic kidney disease patients? CANNT J. 2006;16(4):22–26. | ||

Jillings C. Nursing the system in chronic disease self-management. Can J Nurs Res. 2008;40(3):141–143. | ||

Redman BK. When is patient self-management of chronic disease futile? Chronic Illn. 2011;7(3):181–184. | ||

Rogers A, Kennedy A, Nelson E, Robinson A. Uncovering the limits of patient-centeredness: implementing a self-management trial for chronic illness. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(2):224–239. | ||

Walters JA, Courtney-Pratt H, Cameron-Tucker H, et al. Engaging general practice nurses in chronic disease self-management support in Australia: insights from a controlled trial in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Aust J Prim Health. 2012;18(1):74–79. | ||

Lindqvist G, Hallberg LR. ‘Feelings of guilt due to self-inflicted disease’: a grounded theory of suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). J Health Psychol. 2010;15(3):456–466. | ||

Robinson T. Living with severe hypoxic COPD: the patients’ experience. Nurs Times. 2005;101(7):38–42. | ||

Odencrants S, Ehnfors M, Grobe SJ. Living with COPD: part II. RNs’ experiences of nursing care for patients with COPD and impaired nutritional status. Scand J Caring Sci. 2007;21(1):56–63. | ||

Mason M. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2010;11(3):8. | ||

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. | ||

Knight KM, McGowan L, Dickens C, Bundy C. A systematic review of motivational interviewing in physical health care settings. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11(Pt 2):319–332. | ||

Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91–111. | ||

Yen L, Gillespie J, Rn YH, et al. Health professionals, patients and chronic illness policy: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2010;14(1):10–20. | ||

Wilson PM, Kendall S, Brooks F. Nurses’ responses to expert patients: the rhetoric and reality of self-management in long-term conditions: a grounded theory study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(7):803–818. | ||

Osterlund Efraimsson E, Klang B, Larsson K, Ehrenberg A, Fossum B. Communication and self-management at nurse-led COPD clinics in primary health care. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(2):209–217. | ||

Verbrugge R, de Boer F, Georges JJ. Strategies used by respiratory nurses to stimulate self-management in patients with COPD. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(19–20):2787–2799. | ||

Lundh L, Rosenhall L, Törnkvist L. Care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary health care. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(3):237–246. | ||

Bennet P, Conner M, Godin G. Changing behaviour to improve health. In: Michie S, Abraham C, editors. Health Psychology in Practice. Oxford: Blackwell; 2004:267–281. | ||

Thorne SE, Paterson BL. Health care professional support for self-care management in chronic illness: insights from diabetes research. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;42(1):81–90. | ||

Clark NM, Gong M. Management of chronic disease by practitioners and patients: are we teaching the wrong things? BMJ. 2000;320(7234):572–575. | ||

Funnell MM, Brown TL, Childs BP, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care. 2009;32 Suppl 1:87–94. | ||

Jeffery R. Normal rubbish: deviant patients in casualty departments. Sociol Health Illn. 1979;1(1):90–107. | ||

Bowler I. ‘They’re not the same as us’: midwives’ stereotypes of South Asian descent maternity patients. Sociol Health Illn. 1993;15(2):157–178. | ||

Mir G, Sheikh A. ‘Fasting and prayer don’t concern the doctors … they don’t even know what it is’: communication, decision-making and perceived social relations of Pakistani Muslim patients with long-term illnesses. Ethn Health. 2010;15(4):327–342. | ||

Kendall E, Ehrlich C, Sunderland N, Muenchberger H, Rushton C. Self-managing versus self-management: reinvigorating the socio-political dimensions of self-management. Chronic Illn. 2011;7(1):87–98. | ||

Pinnock H, Hanley J, McCloughan L, et al. Effectiveness of telemonitoring integrated into existing clinical services on hospital admission for exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: researcher blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6070. | ||

Steventon A, Bardsley M, Billings J, et al. Effect of telehealth on use of secondary care and mortality: findings from the Whole System Demonstrator cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e3874. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.