Back to Journals » Cancer Management and Research » Volume 11

Impact of EGFR genotype on the efficacy of osimertinib in EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor-resistant patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a prospective observational study

Authors Igawa S, Ono T, Kasajima M, Ishihara M, Hiyoshi Y, Kusuhara S, Nishinarita N, Fukui T, Kubota M , Sasaki J, Hisashi M, Yokoba M, Katagiri M , Naoki K

Received 28 February 2019

Accepted for publication 29 April 2019

Published 28 May 2019 Volume 2019:11 Pages 4883—4892

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S207170

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Ahmet Emre Eşkazan

Satoshi Igawa,1 Taihei Ono,1 Masashi Kasajima,1 Mikiko Ishihara,1 Yasuhiro Hiyoshi,1 Seiichiro Kusuhara,1 Noriko Nishinarita,1 Tomoya Fukui,1 Masaru Kubota,1 Jiichiro Sasaki,2 Mitsufuji Hisashi,3 Masanori Yokoba,4 Masato Katagiri,4 Katsuhiko Naoki1

1Department of Respiratory Medicine, Kitasato University School of Medicine, Sagamihara-city, Kanagawa, Japan; 2Research and Development Center for New Medical Frontiers, Kitasato University School of Medicine, Sagamihara-city, Kanagawa, Japan; 3Kitasato University School of Nursing, Sagamihara-city, Kanagawa, Japan; 4School of Allied Health Sciences, Kitasato University, Sagamihara-city, Kanagawa 252-0373, Japan

Purpose: A T790M of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is the most frequently encountered mutation conferring acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The aim of this study was to assess the differential clinical outcomes of osimertinib therapy in NSCLC patients with T790M according to the type of activating EGFR mutation, ie, exon 19 deletion or L858R point mutation.

Patients and methods: A prospective observational cohort study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of osimertinib in patients with a major EGFR mutation and T790M-positive advanced NSCLC who had disease progression after first-line EGFR-TKI therapy. The efficacy of osimertinib was evaluated according to the type of EGFR mutation.

Results: A total of 51 patients were included in this study. An objective response was obtained in 29 patients, indicating an objective response rate of 58.8%. The response rate was 69.7% in patients with exon 19 deletion and 38.9% in patients with L858R point mutation, indicating a statistically significant difference (P=0.033). The median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of the entire patient population were 7.8 and 15.5 months, respectively. The median PFS in the exon 19 deletion and L858R point mutation groups was 8.0 months and 5.2 months, respectively, indicating a statistically significant difference (P=0.045). Median OS in the exon 19 deletion and L858R point mutation groups was significantly different at 19.8 months and 12.9 months, respectively (P=0.0015). Multivariate analysis identified the exon 19 deletion as a favorable independent predictor of PFS and OS.

Conclusion: Investigators should consider the proportions of sensitive EGFR mutation types as a stratification factor in designing or reviewing clinical studies involving osimertinib.

Keywords: EGFR genotype, non-small cell lung carcinoma, osimertinib, efficacy

Introduction

Lung cancer is a major cause of cancer-related death. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 85% of all lung cancers.1 Advanced NSCLC with activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene is a distinct subtype of disease that is characterized by a high tumor response rate when treated with small molecule EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Meta-analyses have clearly shown improvements in progression-free survival (PFS) and response rates in patients with EGFR mutations who receive EGFR-TKI therapy, including gefitinib, erlotinib, and afatinib, as compared to those in patients who receive chemotherapy with cytotoxic drugs.2–5 Based on these results, EGFR-TKI has become a standard regimen for patients with advanced NSCLC harboring EGFR mutation. Regarding the efficacy of EGFR-TKI, we previously reported the association between smoking status and efficacy of EGFR-TKI including gefitinib and erlotinib.6,7 Moreover, we reported the association between body size (BSA and BMI) of patients and efficacy of EGFR-TKIs.8 However, despite initial responses to EGFR-TKI therapy, the majority of patients will exhibit disease progression within 1–2 years due to acquired resistance.9–17 In approximately 60% of patients, the mechanism of acquired resistance is the occurrence of an additional EGFR mutation, T790M.16

Osimertinib is a mono-anilino-pyrimidine compound that irreversibly and selectively targets EGFR-TKI-sensitizing and T790M resistance-mutant forms of EGFR, while sparing wild-type EGFR.18–20 A phase I/II AURA trial was conducted to reveal the safety and efficacy of osimertinib in patients with advanced NSCLC who experienced disease progression after previous treatment with EGFR-TKIs.21 Among the patients with a T790M mutation, osimertinib showed high efficacy, with an objective response rate (ORR) of 61% and a median PFS of 9.6 months. To further confirm the results of this, a randomized, phase III AURA (AURA III) trial was conducted that demonstrated the superiority of osimertinib treatment over standard chemotherapy with platinum plus pemetrexed in patients with EGFR-mutated and centrally confirmed T790M-positive advanced NSCLC with disease progression after first-line EGFR-TKI therapy.22 The results of the AURA III trial indicated a significantly longer PFS for patients receiving osimertinib than for those treated with platinum chemotherapy, establishing the role of osimertinib as a standard of care for patients who show disease progression after first-line EGFR-TKI and who harbor the T790M resistance mutation. However, the difference in efficacy of osimertinib among NSCLC patients according to their EGFR genotypes, such as whether they harbor the exon 19 deletion or L858R point mutation, remained unclear. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine whether the EGFR genotype affects the efficacy of osimertinib in patients with advanced NSCLC harboring the T790M mutation.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

We conducted a prospective observational cohort study at Kitasato University Hospital between January 2017 and December 2018 and evaluated the efficacy and safety of osimertinib in patients with T790M-positive advanced NSCLC who showed disease progression after first-line EGFR-TKI therapy, including gefitinib, erlotinib, and afatinib. The eligibility criteria of this study were as follows: histologically or cytologically confirmed NSCLC harboring both an EGFR major mutation and T790M, and stage IV disease or recurrence according to the new Union for International Cancer Control criteria, version 8. We excluded patients who did not have at least one measurable lesion according to the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) 1.1 criteria.1 Patient characteristics, including age at diagnosis, gender, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) at the start of osimertinib treatment, smoking status, clinical stage, tumor histology, brain metastasis status, number of metastatic lesions, and number of previous chemotherapy regimens, were identified by a chart review. The institutional ethics review board of the Kitasato University Hospital approved this study. This prospective observational study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment into this study. After obtaining written consent, the patients were treated with 80 mg of osimertinib daily until disease progression or unacceptable adverse events.

Analysis of EGFR mutations

A sample of the primary tumor, a metastatic lesion, or pleural effusion fluid was used as a specimen to test for EGFR mutations using the PNA-LNA PCR clamp method in the first evaluation of EGFR mutation status. Tumor re-biopsy specimens, along with plasma specimens recovered by liquid biopsy, were tested for EGFR T790M status using the Cobas EGFR Mutation Test (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

Response assessment

After initiation of osimertinib treatment, diagnostic imaging, ie, computed tomography (CT), of the chest and abdomen was carried out every 2–3 months or at more frequent intervals. PET or bone scintigraphy and CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cranium were carried out when patients had significant symptoms associated with tumor lesions or at 6-month intervals. Response to treatment was re-evaluated for this study by two investigators (S.I. and T.O.) according to the RECIST 1.1 criteria.1

Statistical analysis

PFS was measured from the start of osimertinib therapy to treatment failure (death, documentation of disease progression or appearance of unacceptable toxicity) or date of censoring at the last follow-up examination. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the interval between the start of osimertinib therapy and death from any cause or date of censoring. The survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences according to the type of EGFR mutation were analyzed by the log-rank test. Variables including age, gender, smoking status, PS, stage, brain metastasis status, EGFR genotype, and number of prior regimens were used for fitting Cox’s proportional hazard models to predict the hazard ratio for PFS and OS. Differences in the response rates according to the EGFR genotype were compared by Fisher's exact test. A P-value <0.05 was used as the criterion for determining statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software program, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 51 NSCLC patients treated with osimertinib between May 2016 and October 2018 were included in the final analysis. The basic characteristics of the patients were as follows (Table 1): 65% were female, the median age was 71 years, and 67% had a good PS (PS 0 or 1). All patients had adenocarcinoma (51 patients, 100%). The exon 19 deletion was found in 33 (65%) patients, and the L858R point mutation in 18 (35%). The results for the categorical variables showed that there were significantly higher percentages of females and non-elderly patients (<75 years) in the exon 19 deletion group than in the L858R point mutation group (Table 2).

| Table 1 Patient characteristics |

| Table 2 Patient characteristics according to EGFR genotype |

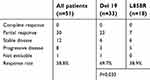

Response to osimertinib according to EGFR genotype

Table 3 shows objective tumor responses. An objective response was obtained in 29 of the 51 patients, indicating an objective response rate (ORR) of 58.8% (95% confidence interval [CI]=42.3–75.3%). The response rate was 69.7% (95% CI=50.0–89.4%) in patients with exon 19 deletion and 38.9% (95% CI=18.0–59.7%) in patients with L858R mutation, indicating a statistically significant difference (P=0.033). Among patients showing a partial response, there was no significant difference in the median time to response between the two genotypes, with values of 1.8 months for the exon 19 deletion group and 1.4 months for the L858R point mutation group (P=0.61, Figure 1).

| Table 3 Response rates according to EGFR genotype |

| Figure 1 Time to response to osimertinib therapy according to EGFR genotype. |

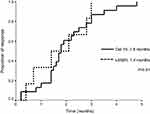

Survival analysis

The cut-off date for the survival data update was February 2019. The median follow-up period at the time of survival analysis was 11.3 months. The median PFS and OS of the entire patient population were 7.8 months (95% CI=6.7–8.9 months, Figure 2A) and 15.5 months (95% CI=10.0–21.0 months, Figure 2B), respectively. Median PFS in the exon 19 deletion group and L858R group was 8.0 months (95% CI=6.4–9.6 months) and 5.2 months (95% CI=3.5–6.9 months), respectively, indicating a statistically significant difference (P=0.045, Figure 3A). Median OS in the exon 19 deletion group and L858R group was 19.8 months (95% CI=13.0–26.6 months) and 12.9 months (95% CI=1.9–23.9 months), respectively, indicating a statistically significant difference (P<0.0015, Figure 3B). The multivariate analysis identified EGFR genotype and number of prior regimens as independent predictors of PFS (Table 4). Additionally, the multivariate analysis identified PS, EGFR genotype, brain metastasis, and stage as independent prognostic factors of OS (Table 5).

| Table 4 Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for progression-free survival |

| Table 5 Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for overall survival |

| Figure 2 Kaplan-Meier plots of (A) PFS; and (B) OS for all patients. |

| Figure 3 Kaplan-Meier plots of (A) PFSand (B) OS according to EGFR genotype. |

Discussion

The advent of targeted therapy has revolutionized treatment for a subset of patients with NSCLC, and testing patients with newly-diagnosed NSCLC for the presence of an EGFR mutation is now considered the standard of care. However, in approximately 60% of patients, the mechanism of acquired resistance to first- or second-generation EGFR-TKIs is the occurrence of an additional EGFR mutation, T790M,23 and osimertinib is a key drug for the treatment of patients with acquired resistance by T790M mutation. The results of the present study showed that the response rate, PFS, and OS differed significantly according to EGFR genotype among patients with T790M-positive advanced NSCLC who had disease progression after first-line EGFR-TKI therapy. To our knowledge, this is the first report prospectively evaluating the relationship between the efficacy of osimertinib treatment and the EGFR genotype in NSCLC patients limited to the Asian population, and showing that the exon 19 deletion group had significantly better clinical outcomes including response rate, PFS, and OS compared with the L858R group.

OPTIMAL and ENSURE, phase III studies that evaluated erlotinib compared with platinum doublets, showed a trend toward improved PFS in patients with exon 19 deletions compared with that in patients with L858R point mutations.24,25 Another prospective study of 36 patients treated with either gefitinib or erlotinib observed improved OS among patients with exon 19 deletions as compared with that among patients with L858R point mutation, as well as trends toward higher response rates and improved PFS.26 Moreover, in a phase III trial comparing erlotinib with gefitinib in NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations,27 it was shown that patients with EGFR exon 19 deletions had a significantly higher response rate and longer median OS than those with L858R point mutations treated with erlotinib or gefitinib. A recent meta-analysis using randomized trial data from studies of patients receiving first-line treatment with first- and second-generation EGFR-TKIs revealed an impact of mutation subtype on PFS outcome.28 In the meta-analysis, a total of seven studies involving 1,649 patients treated with gefitinib, erlotinib, or afatinib were included, and the majority of patients harbored common EGFR mutations, including 872 patients with exon 19 deletion and 686 patients with L858R point mutations. Patients with exon 19 deletion showed a significantly greater PFS benefit when treated with an EGFR-TKI than did patients with L858R point mutation. Likewise, another meta-analysis reported that exon 19 deletion was associated with longer PFS compared to L858 mutation upon treatment with first- or second-generation EGFR-TKIs.29 Moreover, another study used kinetic analysis of these two mutations to show that tumors harboring exon 19 deletions appeared to be more sensitive to erlotinib inhibition than tumors harboring L858R.30 Importantly, Auriac et al31 reported a retrospective study, indicating that patients with exon 19 deletion showed a significantly longer PFS and OS when treated with osimertinib than did patients with L858R point mutation. Likewise, there was a trend toward an increased response rate in patients who had co-occurring EGFR T790M mutations and exon 19 deletions, vs that in patients with EGFR T790M mutations with L858R (70% vs 57%) in a pooled analysis of two previously reported phase 2 studies (AURA extension and AURA2).32 Table 6 summarizes the results of studies that compared the efficacy of osimertinib in terms of PFS and OS according to the EGFR mutation sub-type. Regarding the efficacy of osimertinib in patients with untreated EGFR-mutated NSCLC, FLAURA, a global phase III study33 showed that PFS of patients with exon 19 deletions and those with L858R were 21.4 months and 14.4 months, indicating a trend toward an increased PFS in the exon 19 deletion group compared with that in the L858R group. Therefore, the findings of our study support the results of these previous reports.

| Table 6 Summary of studies comparing the efficacy of osimertinib for advanced NSCLC according to subtype of EGFR mutation |

Additionally, there has been a report that the IC50 of osimertinib seems to be lower in PC-9 cells harboring an exon 19 deletion than in tumor H3255 cells harboring L858R according to an in vitro analysis.18

A previous study demonstrated that the tumor mutation burden (TMB) was lower in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC than in those with wild-type EGFR; however, the TMB in patients with a L858R point mutation was significantly higher than that in patients with an exon 19 deletion.34 In addition, the study showed that the clinical benefit of first- or second-generation EGFR-TKI therapy was significantly less in the high-TMB group than in the low-TMB group.34 Based on these findings, it is reasonable to hypothesize that EGFR-TKIs are more effective in NSCLC patients with exon 19 deletion than in those with L858R point mutation due to differences in TMB between the EGFR genotypes.

A previous phase III (AURA III) trial reported an ORR to osimertinib of 71% (95% CI=65–76) and a PFS of 10.1 months in patients with T790M-positive advanced NSCLC who had disease progression after failure of first-line EGFR-TKI therapy.22 The response rate and PFS in the AURA III study appear to be higher than those in our study. In the AURA III study, not only did all of the patients have good PS, but also 96% of the patients had received only one prior regimen. In contrast, in our study, the number of patients with poor PS was 17 (33%) and the median number of chemotherapy regimens prior to osimertinib therapy per patient was two, likely explaining the differences in ORR and PFS between the AURA III trial and our study.

Further investigation is needed to clarify the differences in the efficacy of osimertinib according to the EGFR genotype of NSCLC patients based on in vitro or in vivo pre-clinical data. There were several limitations to our study. First, the sample size and median follow-up time may not have been sufficient, and this study was performed at a single institution. Second, there was an imbalance in patient characteristics between patients harboring the exon 19 deletion and those harboring the L858R point mutation. Third, whereas evidence showing that osimertinib is mostly recommended for treatment of advanced NSCLC patients with EGFR mutation as a first-line chemotherapy was recently established,33 we did not evaluate the issue of osimertinib therapy in the first-line setting.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we revealed that patients with an EGFR genotype of exon 19 deletion had better clinical outcomes among advanced NSCLC patients treated with osimertinib as second-line therapy after the failure of first-line EGFR-TKI therapy. The result of the present study provides important information, suggesting that investigators should consider the proportions of various types of sensitive EGFR mutations as a stratification factor in designing or reviewing clinical studies involving osimertinib.

Key points

Osimertinib response rates, PFS and OS were affected by the type of EGFR mutation. Multivariate analysis indicated that the number of prior regimens, stage, and EGFR mutation were independent predictors of PFS and OS.

Ethics approval and informed consent

The institutional ethics review board of the Kitasato University Hospital approved this study. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment into this prospective observational study.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff members of the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Kitasato University School of Medicine for their suggestions and assistance.

Disclosure

Dr Tomoya Fukui reports personal fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim Japan Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., MSD K.K., Novartis Pharma K.K., Pfizer Japan Inc., Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., AstraZeneca K.K., outside the submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):220–241. doi:10.3322/caac.21149

2. Bria E, Milella M, Cuppone F, et al. Outcome of advanced NSCLC patients harboring sensitizing EGFR mutations randomized to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors or chemotherapy as first-line treatment: a meta analysis. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(10):2277–2285. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq731

3. Petrelli F, Borgonovo K, Cabiddu M, et al. Efficacy of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with EGFR-mutated non–small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of 13 randomized trials. Clin Lung Cancer. 2012;13(2):107–114. doi:10.1016/j.cllc.2011.08.005

4. Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304(5676):1497–1500. doi:10.1126/science.1099314

5. Miyawaki M, Naoki K, Yoda S, et al. Erlotinib as second- or third-line treatment in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Keio Lung Oncology Group Study 001 (KLOG001). Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6(3):409–414. doi:10.3892/mco.2017.1154

6. Igawa S, Sasaki J, Otani S, et al. Impact of smoking history on the efficacy of gefitinib in patients with non-small cell lung cancer harboring activating epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. Oncology. 2015;89(5):275–280. doi:10.1159/000438703

7. Nishinarita N, Igawa S, Kasajima M, et al. Smoking history as a predictor of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR mutations. Oncology. 2018;95(2):109–115. doi:10.1159/000488594

8. Igawa S, Kasajima M, Ishihara M, et al. Evaluation of gefitinib efficacy according to body surface area in patients with non-small cell lung cancer harboring an EGFR mutation. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74(5):939–946. doi:10.1007/s00280-014-2570-1

9. Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):121–128. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X

10. Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;1(3):239–246. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X

11. Han JY, Park K, Kim SW, et al. First-SIGNAL: first-line single-agent iressa versus gemcitabine and cisplatin trial in never-smokers with adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(10):1122–1128. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8456

12. Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Maemondo M, et al. Updated overall survival results from a randomized phase III trial comparing gefitinib with carboplatin-paclitaxel for chemo-naïve non-small cell lung cancer with sensitive EGFR gene mutations (NEJ002). Ann Oncol. 2013;24(1):54–59. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds214

13. Fukuoka M, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Biomarker analyses and final overall survival results from a phase III, randomized, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel in clinically selected patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in Asia (IPASS). J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(21):2866–2874. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4235

14. Terai H, Soejima K, Yasuda H, et al. Activation of the FGF2-FGFR1 autocrine pathway: a novel mechanism of acquired resistance to gefitinib in NSCLC. Mol Cancer Res. 2013;11(7):759–767. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0652

15. Terai H, Soejima K, Yasuda H, et al. Long-term exposure to gefitinib induces acquired resistance through DNA methylation changes in the EGFR-mutant PC9 lung cancer cell line. Int J Oncol. 2015;46(1):430–436. doi:10.3892/ijo.2014.2733

16. Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(27):3327–3334. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.49.0219

17. Park K, Tan EH, O’Byrne K, et al. Afatinib versus gefitinib as first-line treatment of patients with EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (LUX-Lung 7): a phase 2B, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(5):577–589. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30033-X

18. Cross DA, Ashton SE, Ghiorghiu S, et al. AZD9291, an irreversible EGFR TKI, overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(9):1046–1061. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0646

19. Hirano T, Yasuda H, Tani T, et al. In vitro modeling to determine mutation specificity of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors against clinically relevant EGFR mutants in non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6(36):38789–38803. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.5887

20. Masuzawa K, Yasuda H, Hamamoto J, et al. Characterization of the efficacies of osimertinib and nazartinib against cells expressing clinically relevant epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. Oncotarget. 2017;8(62):105479–105491. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.22297

21. Jänne PA, Yang JC, Kim DW, et al. AZD9291 in EGFR inhibitor-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(18):1689–1699. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1411817

22. Mok TS, Wu Y-L, Ahn M-J, et al. Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):629–640. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1612674

23. Cortot AB, Jänne PA. Molecular mechanisms of resistance in epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant lung adenocarcinomas. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;23(133):356–366. doi:10.1183/09059180.00004614

24. Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, openlabel, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:735–742. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70150-4

25. Wu YL, Zhou C, Liam CK, et al. First-line erlotinib versus gemcitabine/cisplatin in patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: analyses from the phase III, randomized, open-label, ENSURE study. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1883–1889. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdv383

26. Jackman DM, Yeap BY, Sequist LV, et al. Exon 19 deletion mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor are associated with prolonged survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib or erlotinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(13):3908–3914. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0462

27. Yang JJ, Zhou Q, Yan HH, et al. A phase III randomised controlled trial of erlotinib vs gefitinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer with EGFR mutations. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(5):568–574. doi:10.1038/bjc.2016.456

28. Lee CK, Wu YL, Ding PN, et al. Impact of specific epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations and clinical characteristics on outcomes after treatment with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors versus chemotherapy in EGFR-mutant lung cancer: A meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1958–1965. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.58.1736

29. Zhang Y, Sheng J, Kang S. Patients with exon 19 deletion were associated with longer progression-free survival compared to those with L858R mutation after first-line EGFR-TKIs for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107161. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107161

30. Carey KD, Garton AJ, Romero MS, et al. Kinetic analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor somatic mutant proteins shows increased sensitivity to the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, erlotinib. Cancer Res. 2006;66(16):8163–8171. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0453

31. Auliac JB, Pérol M, Planchard D, et al. Real-life efficacy of osimertinib in pretreated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR T790M mutation. Lung Cancer. 2019;127:96–102. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.11.037

32. Ahn MJ, Tsai CM, Shepherd FA, et al. Osimertinib in patients with T790M mutation-positive, advanced non-small cell lung cancer: long-term follow-up from a pooled analysis of 2 phase 2 studies. Cancer. 2019;125:892–901. doi:10.1002/cncr.31891

33. Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):113–125. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1711583

34. Offin M, Rizvi H, Tenet M, et al. Tumor mutation burden and efficacy of EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(3):1063–1069. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1102

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.