Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 13

How Inclusive Leadership Enhances Follower Taking Charge: The Mediating Role of Affective Commitment and the Moderating Role of Traditionality

Authors Wang Q, Wang J, Zhou X, Li F, Wang M

Received 8 September 2020

Accepted for publication 3 November 2020

Published 1 December 2020 Volume 2020:13 Pages 1103—1114

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S280911

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Einar Thorsteinsson

Qiao Wang,1 Jianmin Wang,2 Xiaohu Zhou,1 Fangyuan Li,1 Mengze Wang1

1School of Economics and Management, Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing, People’s Republic of China; 2College of Public Management, Guizhou University of Finance and Economics, Guiyang, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Jianmin Wang; Xiaohu Zhou Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Purpose: Leaders try to stimulate follower taking charge to promote organizational change and effectiveness in current increasingly complex and changing environment. Based on social identity theory, we developed a mediated moderation model in which affective commitment was theorized as a mediating mechanism underlining why followers feel motivated to taking charge with the supervision of inclusive leadership. Furthermore, traditionality should be a relevant boundary condition to moderate such a relationship in China.

Methods: There was three times lagged research conducted at the city of Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Nanjing. A series of valid questionnaires were accomplished by 246 participants, including the inclusive leadership, affective commitment, traditionality, and follower taking charge. Our model adopted hierarchical regression analysis to explore hypothesis.

Results: Inclusive leadership is positively related to affective commitment (β= 0.589, p < 0.001). Affective commitment was positively related to follower taking charge (β= 0.165, p < 0.01). Affective commitment mediates the relationship between inclusive leadership and taking charge with 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals [0.068, 0.233]. Interactive effect of affective commitment and traditionality on follower taking charge was also significant (β=– 0.189, p < 0.001), and the effect of affective commitment on follower taking charge was more pronounced and positive with low (b = 0.361, p < 0.001) rather than high (b =0.172, ns.) level of affective commitment. Moreover, the indirect effect of inclusive leadership on taking charge through affective commitment was significant when traditionality was low (b = 0.270, 95% CI = [0.179, 0.371]), the indirect effect became insignificant with high traditionality (b = 0.046, 95% CI = [– 0.034, 0.123]).

Conclusion: Our study shows that affective commitment mediates the relationship between inclusive leadership and follower taking charge. Moreover, the influence of affective commitment on follower taking charge was moderated by traditionality. Affective commitment was positively associated with taking charge only for followers with low traditionality. Additionally, the mediated moderation relationship between inclusive leadership and follower taking charge via affective commitment was stronger under low traditionality.

Keywords: inclusive leadership, affective commitment, traditionality, follower taking charge, social identity theory

Introduction

Recently, a new competitive environment featuring economic globalization, mobile Internet, and big data has made organizational change as a normal. Whereas proactive behavior is an important factor in the organization’s rapid development.1,2 Therefore, how to effectively stimulate employees’ proactive behaviors have become an important issue in organizational management. As an important form of proactive behavior, the positive effect of taking charge of organizational change and development has been more verified.3–5 Taking charge has been defined as voluntary and constructive efforts, by individual subordinates, to effect organizationally functional change concerning how work is executed within the contexts of their jobs, work units, or organizations6 which is risky for followers to implement taking charge. Therefore, the inclusiveness and support of leaders for followers’ trial and error is the basic condition for followers to actively engage in taking charge.

Inclusive leadership shows accessibility, interactive, fair, and error-tolerant in the process of interaction with followers.7–9 Inclusive leadership is different from other leadership styles,7 which encourages employees to put forward their own views and ideas boldly, and is tolerant of employees’ trial and error behavior, which helps to promote a positive impact on employee’s working attitude and working behavior under diverse conditions,8−10−13 such as innovative behavior,14,15 employee involvement16 and organizational citizenship behavior.17 Previous studies have shown that leadership behavior is an important predictor of taking charge.5,18–22 Although Zeng et al23 examined the relationship between inclusive leadership and taking charge, which was based on the perspective of self-determination and social information processing to explain the influence of inclusive leadership on taking charge, but ignored the emotional factors of employees. Because it is not a simple contractual exchange relationship between employees and organizations, and their interaction process is often mixed with complex emotional factors,24,25 which is difficult to systematically explain the effect of inclusive leadership on taking charge from a cognitive perspective. Therefore, it still contains key gaps that explain how inclusive leadership affects followers’ taking charge from an emotional perspective.

Our study uses social identity theory26 to illuminate the gap how inclusive leadership relates to follower taking charge from affective commitment perspective. According to social identity theory,26,27 under the influence of leader’ behavior of inclusive leadership, followers’ sense of identity and belonging to the organization will be increased,28 and followers’ degree of psychological recognition and acceptance of organizational prospects and values also will be improved,29 which would promote followers to produce affective commitment to the organization. Affective commitment is closely related to followers’ willingness to maintain the organization’s honor and take corresponding actions for organizational development,30,31 such as taking charge. Therefore, in order to explore the emotional mediating mechanism of inclusive leadership influencing followers’ taking charge, this research examines how inclusive leadership influences followers’ taking charge through the potential mechanism of affective commitment.

In the context of Chinese culture, the influence of culture cannot be ignored when exploring followers’ psychology and behavior,32,33 such as, China has an old saying “one who sticks his neck out gets hit first”, which emphasizes low-key compliance. The difference between individual’s personality and values has an impact on the final influence of inclusive leadership.34 Li et al35 and Yao et al36 believe that the difference of followers traditionality may affect the effect of leadership behavior on employee outcomes. Traditionality is not only one of the most concerned cultural values in the transitional period of Chinese society,32 but also the most closely related to the study of affective commitment.37,38 Therefore, our research explores the moderating effect of follower traditionality between inclusive leadership, affective commitment, and taking charge in the context of organizational management in China.

Our research makes three contributions to the extant literature. First, it extends the existing influence of inclusive leadership to follower affective commitment, thereby enriching the literature on inclusive leadership. Second, drawing on social identity theory, our study explores affective commitment as an important mediating mechanism through which inclusive leadership influence follower taking charge, which is from the perspective of emotion and makes up for the monotony of exploring only from the cognitive perspective.23 At the same time, it also responds to Randel et al39 call to explore the relationship between inclusiveness and employee behavior outcomes with social identity theory. Third, we propose traditionality as a boundary condition which moderates the impacts of inclusive leadership on nurturing affective commitment and consequent follower taking charge in China. The interplay between affective commitment and traditionality in boosting the processes of follower taking charge provides theoretical and practical values. Figure 1 shows the complete research model.

|

Figure 1 Hypothesized research model. |

Theory and Hypothesis

Inclusive Leadership and Affective Commitment

“Inclusiveness” is a relatively new concept in the field of organizational research. In the early stage, inclusive was mainly used in the field of education. Scholars put forward the concept of “inclusive education” because of the phenomenon of educational diversity and differentiation in Western schools, calling on educators to treat students with differences in race, social status and religion equally.40 It was not until 2006 that Nembhard and Edmondson7 introduced the concept of inclusive leadership into the study of leadership. Inclusive leadership is a leadership style in which managers are adept at listening to subordinates’ views and recognizing their contributions.41 Inclusive leadership, as an effective way of leadership in the new type of leadership, emphasizes the establishment of good relationship in the process of interaction with subordinates and encourages employees to actively participate in the organization through the accessibility, interactive, fair, and fault-tolerant of leadership, to realize the support of the organization for employees.16 Moreover, inclusive leadership emphasizes the individual’s sense of belonging and unique values, through the inclusion of all members in the working group and the promotion of their different contributions and abilities,7,39 which is different from other leadership styles.39 For example, transformational leadership influences subordinates by expanding and upgrading their followers’ goals, so that they have confidence to surpass the expectations stipulated in implicit or explicit exchange agreements;42 empowering leadership is to share power with subordinates and improve their internal incentive level;43 servant leadership does not emphasize the individual’s self-interest but focuses on the individual’s moral responsibility to create success for the organization, members and other stakeholders.44

Affective commitment is the core dimension of organizational commitment.45,46 As a positive emotion, it reflects “the degree of employees’ identification, involved and affective attachment to the organization”45 Previous studies have shown that leadership trust47,48 and organizational support47,49 can effectively promote followers’ affective commitment. According to social identity theory,26 inclusive leadership can promote followers to feel that they are part of the team, and increase the sense of belonging of followers.39,50 Specifically, the impact of inclusive leadership on followers’ affective commitment is mainly reflected in the following three aspects. Firstly, Inclusive leadership can treat followers with different backgrounds equally and pay special attention to the benefit distribution of disadvantaged groups in the organization,51 so that followers can feel the care and care from leaders,52 which makes followers feel respected, and then enhances their organizational identification. Secondly, inclusive leadership tolerates the personalized characteristics of subordinates and encourages individuals with different backgrounds and different values to fully express themselves.16 Inviting followers to attend the decision-making process, encouraging and accepting the expression of different opinions of employees, and recognizing employees’ contributions, so that followers can fully feel the significance of their work and their influence on the work, and further promote followers involved in the organization.16 Thirdly, inclusive leadership encourages all followers to seek help at any time when new problems arise. Especially when followers make mistakes in their work, inclusive leadership can forgive their mistakes with a tolerant attitude and provide professional guidance to followers in a timely manner,39,53 which make followers feel valued and supported by leaders, and improve followers’ affective commitment. This leads to:

Hypothesis 1: Inclusive leadership is positively related to affective commitment.

Affective Commitment and Taking Charge

Taking charge is a follower’s discretionary behavior, which conducts constructive change and could produce positive affects in job performance and organizational effectiveness.6,54 Different from other proactive behaviors, such as innovative behavior, voice, and so on,1,2,55–57 taking charge has the characteristics of proactive, change-oriented, and risky.3,22 Therefore, whether followers to engage in taking charge depends on the style of leadership in organizations.5,18,21,22,54

According to social identity theory,26,58 when followers identify with the good reputation of an organization, followers will strive to strive for and maintain positive organizational identity,59,60 thus generating a sense of responsibility for organizational rewards.28 Previous studies have shown that affective commitment can effectively predict followers’ proactive behavior,16,17,61 while taking charge is defined as a challenging and improving organizational efficiency behavior.4,6 Therefore, affective commitment may be an important antecedent variable of taking charge, which is divided into three aspects: Firstly, when the employees’ affective commitment level is high, they have a higher degree of identification and affective attachment to the organization, are more willing to contribute to the development of the organization, and focus on making organizational change better so as to make taking change behavior. Secondly, employees feel that leaders have invested a lot in them when they have a high-level affective commitment, which is also conducive to reducing or even eliminating employees’ worries about the risk of taking charge, and would promote employees’ taking change. Thirdly, followers with high affective commitment will be more enthusiastic about investing in the organization and maintaining the interests and image of the organization spontaneously. They have deep feelings for the organization that transcend benefits. Therefore, even if they may bear the risks brought about by the failure of taking charge, the emotional attachment to the organization can prompt them to take the initiative to take responsibility for their work and make suggestions for improvement regardless of their personal interests. As a result, employees with high levels of affective commitment are often able to overcome the risks and difficulties faced by transformative behaviors and exhibit more taking charge. Hence, the second hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Affective commitment is positively related to follower taking charge.

The Mediator Role of Affective Commitment

Building upon social identity theory, inclusive leadership can promote organizational employees to feel that they are part of the team, and increase the sense of belonging of employees, which will produce a sense of responsibility to repay the organization.50 And combined with the above argument with Hypotheses 1 and 2, we also can forecast inclusive leadership impacts follower taking charge indirectly through affective commitment. Namely, the leadership behavior of inclusive leadership enables follower to acquire high-level affective commitment. Studies have shown that high-level affective commitment is closely related to followers’ high sense of identity and loyalty, which makes employees think that they have responsibility and obligation to contribute to organizational development.62 Then, followers with a high-level affective commitment would have greater levels of identification, involved and affective attachment to the organization, and feel obligated to make beneficial work-related behaviors,25,62 such as taking charge. In this process, followers’ affective commitment as a mechanism that mediates the impact of inclusive leadership on follower taking charge. Therefore, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 3: Affective commitment mediates the relationship between inclusive leadership and follower taking charge.

The Moderating Role of Traditionality

Traditionality is considered to be the best reflect of the traditional Chinese character and value orientation,63 which describes the individual’s recognition of traditional Confucian ideas such as “following authority, being safe and upright, self-preservation of destiny, filial piety and ancestor worship, and male superiority”.64,65 There are many differences in attitudes and behavior patterns between the group of high traditionality and low traditionality. Followers with high traditionality comply with traditional social role obligations, while followers with low traditionality follow the principle of incentive contribution balance.32 Traditionality is an important value influencing factor that constrains the behavior of contemporary Chinese. Therefore, in the field of organizational management research, scholars regard it as an important moderating variable between organizational context variables and employee-related results.36,66–68 For example, Zhao37 explored the moderating role of traditionality in the impact of affective commitment on employee voice, and Juma and Lee38 also supported the moderating role of traditionality in the influence of internal labor market relationship on affective commitment and turnover intention.

In general, followers with different traditionalities will behave differently even if they are in the same organizational situation. Therefore, in the context of affective commitment, followers with different traditionalities may have different responses. From the perspective of social identity theory, affective commitment represents the degree of employees’ identification with the organization. Followers with highly traditionality have the characteristics of being safe and stable depend, and the work-related attitudes and behaviors of followers with highly traditionality depend more on the responsibilities and obligations related to their work roles (ie, role constraints),66 and will not be different because of their recognition of the good reputation of the organization. On the other hand, followers with low traditionality, are independent, confident, open, willing to pursue personal values, like challenging goals and continuous improvement, and actively implement novel ideas.35 Therefore, facing the inclusive leadership lead to affective commitment, for followers with highly traditionality, they tend to choose “cautious” and “risk off” behavior, and will take into account the interpersonal harmony within the organization and avoid the interpersonal conflict, they will still adhere to their own work role settings, think that they are “inferior” in the organization,69 dare not violate the rules and regulations of the organization,70 and cannot to implement taking charge with risk. Followers with low traditionality dare to break unreasonable organizational rules and regulations, and are carefree to interpersonal relationship and harmonious atmosphere of the organization, and will implement taking charge to help the organizational improvement. Besides, even in the case of low affective commitment, followers with low traditionality are willing to pursue personal value, and they may also make taking charge to improve organizational management efficiency. Therefore, the following hypothesize are proposed:

Hypothesis 4: The relationship between affective commitment and taking charge will be stronger when followers have a lower rather than higher level of traditionality.

According to the above discussion, in addition to the moderating effects of traditionality on the relationship between affective commitment and taking charge, we further anticipate that traditionality will conditionally influence the strength of the indirect relationship between inclusive leadership and taking charge. Specifically, affective commitment plays a mediating role in the influence of inclusive leadership on follower taking charge, and the mediating effect is affected by follower s’ traditionality. When employees’ traditionality is low, inclusive leadership transmits or mediates the indirect effect of inclusive leadership on follower taking charge through affective commitment. Correspondingly, when employees’ traditionality is high, the indirect impact of inclusive leadership on follower taking charge through affective commitment is relatively small. Therefore, our final hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 5: traditionality will moderate the mediated effect of inclusive leadership on follower taking charge via affective commitment such that the indirect relationship will be stronger when there is a lower rather than higher level of traditionality.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

We sent a survey request to the students of an Executive Master of Business Administration (EMBA) class in a university in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province. We got 15 responses and agreed to investigate in their company. These students are the CEO of the company or the head of relevant departments. Our data have collected all variables with three time lagged to avoid the influence of common method bias.71,72 The procedure of survey is as follows. Firstly, we requested the HR manager to select about 30 participants randomly to deliver the surveys. Secondly, before the formal fill in the questionnaire, our team would explain the purpose of our study, and introduce the confidentiality and anonymity of our survey. Also, we put 20 RMB into the envelope with the questionnaires by each round of data collection. The HR manager helped us to collect the questionnaires and return in sealed envelopes. At time 1 (T1), we sent out questionnaires to participants to measure their demographic variables and inclusive leadership. At time 2 (T2, 1 month later), we sent out questionnaires to participants, including affective commitment and traditionality. At time 3 (T3, 2 months later), we asked our participants to evaluate their taking charge.

We collected a total of 325 valid questionnaires at T1 (sent out 390 questionnaires), and the returned rate of valid questionnaires was 83.33%. Two hundred and eighty-nine valid questionnaires were returned at T2, and the returned rate of valid questionnaire was 88.92%. At T3, 246 valid questionnaires were retrieved, the returned rate of questionnaire was 85.12%. Most respondents were male (52.85%), below 30 years of age (65.85%), and had a Master's degree or above degree (28.46%). The team tenure below 3 years was 32.11%, and the income above 10,000 RMB was 58.54%. Lastly, most participants were ordinary employees (77.64%).

Ethical Statement

Our research was conducted based on the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Economics and Management of Nanjing University of Science and Technology. We provided the written informed consent form together with the questionnaire to all participants and introduced the purpose of our research to participants. Moreover, we told participators that our research adopts the principle of voluntary participation, would keep the participants’ answers strictly confidential, and no individual or organization can access the data except the investigators. All participants understand the purpose of our research and agree to participate voluntarily.

Measures

Our study translated all survey instruments into Chinese following the back-translation procedure of Brislin.73 All responses were measured on the 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6=strongly agree).

Inclusive Leadership

Participants accessed their supervisor’s inclusive leadership using the 9-item measure by Carmeli et al.16 A sample item is “My direct leadership is open to hearing new ideas”. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.884.

Affective Commitment

Participants indicated the level of affective commitment they experienced in the workplace using a 6-item measure, which was originally developed by Meyer et al74 and later applied in China by Zhao.75 Two sample items are “I really feel as if this organization’s problems are my own” and “This organization has a great deal of personal meaning for me”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.814.

Traditionality

Participants rated the their traditionality using the 5-item scale by Farh et al64 Two sample items are “The best way to avoid mistakes is to follow the instructions of senior person” and “When people are in dispute, they should ask the most senior person to decide who is right”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.791.

Taking Charge

Participants evaluated their taking charge using a 10-item measure by Morrison and Phelps.6 A sample item is “I often try to correct a faulty procedure or practice”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.854.

Control Variables

On account of the potential influence of individual demographics, our research controlled for gender, age, education, job tenure, which have been found to impact on taking charge.6 Meanwhile, we asked team members to report their incomes and duty, because those maybe an antecedent of taking charge.18,22

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Due to examining data, we adopt CFA to evaluate variables’ validity. Results of the tests of competing CFA models are shown in Table 1. The results of the hypothesized four-factor measurement model show a good model fit (χ2 = 594.618, df = 399, IFI = 0.934, TLI = 0.927, TLI = 0.933, RMSEA = 0.045), which is better than alternative measurement models. Those outcomes offer support for the discriminant and convergent validity of our measures.

|

Table 1 Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

Common Method Variance (CMV)

Although data were collected from three time points to mitigate the influence of CMV,71 all variables were derived from the self-report of participants, there may cause problems of CMV. Our research adopt the single-factor test method of Hair et al76 to test CMV, the outcomes show that the first factor could explain 24.187% of variances, which is far below 40%. It shows that the CMV of the data is not serious and would not impact the reliability of the research conclusion.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and the correlations among the study variables. As expected, the core study variables were significantly related with each other. Specifically, inclusive leadership was positively associated with affective commitment (r = 0.587, p < 0.01) and taking charge (r = 0.167, p < 0.01). Affective commitment was positively related to taking charge (r = 0.285, p < 0.01). In addition, traditionality was negatively related to affective commitment (r =−0.367, p < 0.01), while it was positively related to taking charge (r = 0.404, p < 0.01).

|

Table 2 Results of Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations |

Hypothesis Testing

Our study adept a hierarchical multiple regression techniques to analyze Hypotheses 1, 2, and 4 by adding the dependent variable (follower taking charge), the control variable, independent variable (inclusive leadership), mediator variable (affective commitment), moderator variable (traditionality), and interaction variable (affective commitment multiplied by traditionality) on separate steps.

Hypothesis 1 proposes a positive relationship between inclusive leadership and affective commitment. Table 3 shows the outcomes of Model 2, inclusive leadership was positively related to affective commitment (β= 0.589, p < 0.001). Hence, hypothesis 1 is supported.

|

Table 3 Results of Hierarchical Regression Analysis |

Hypothesis 2 predicts a positive relationship between affective commitment and follower taking charge. Table 3 indicates the results of Model, affective commitment was positively related to follower taking charge (β= 0.165, p < 0.01). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

Hypothesis 3 proposes that affective commitment mediated the relationship between inclusive leadership and follower taking charge, our research adopt bias-corrected bootstrapping techniques by Hayes77 PROCESS macro to test the mediation effect. The outcomes showed that there was a significant indirect effect via affective commitment with 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals [0.068, 0.233] based on 5000 bootstrapped samples in Table 4. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

|

Table 4 Results of Mediation and Mediated Moderation Analysis |

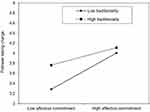

Hypothesis 4 predicts the interactive effect of affective commitment and traditionality on follower taking charge was also significant (β=–0.189, p <0.001, Model 6). We drew an interaction plot following the procedures recommended by Dawson.78 Simple slope test results in Figure 2 show that the effect of affective commitment on follower taking charge was more pronounced and positive with low (b = 0.361, p <0.001) rather than high (b =0.172, ns.) level of affective commitment. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is supported.

|

Figure 2 Interactive effect of affective commitment and traditionality on follower taking charge. |

Hypothesis 5 proposes that traditionality moderates the indirect effects of inclusive leadership on taking charge through affective commitment. Our study adept the model 14 of PROCESS macro of Hayes77 which offers an overall index of the mediated moderation to test the differences of indirect effects at high (1 SD above the mean) and low (1 SD below the mean) levels of the moderator.As shown in Table 4, the indirect effect of inclusive leadership on taking charge through affective commitment was significant when traditionality was low (b = 0.270, 95% CI = [0.179, 0.371]). However, the indirect effect became insignificant with high traditionality (b = 0.046, 95% CI = [–0.034, 0.123]). Therefore, Hypothesis 5 is supported.

Discussion

We explored how and when inclusive leadership facilitates follower taking charge. Our research theorized and empirically tested inclusive leadership enhanced follower’s taking charge. Drawing on social identity theory, our study examined that affective commitment mediates the relationship between inclusive leadership and follower taking charge. Moreover, the influence of affective commitment on follower taking charge was moderated by traditionality. Affective commitment was positively associated with taking charge only for followers with low traditionality. Finally, results indicated that the mediated moderation relationship between inclusive leadership and follower taking charge via affective commitment was stronger under low traditionality.

Theoretical Implications

Our study has three theoretical contributions to the existing literature on inclusive leadership and taking charge. First, our study promotes the understanding that inclusive leadership is a positive effect on taking charge. Previous studies about inclusive leadership have explored the impact on proactive behaviors, such as voice,12,34 and organizational citizenship behavior.17 Previous research is associated with taking charge as a prosocial and a discretionary behavior of boosting organizational effectiveness.6 However, the influence of inclusive leadership on taking charge has not thoroughly explored,23 which is from a cognitive perspective. We provide empirical evidence with the relationship of inclusive leadership and follower taking charge from an emotional perspective.

Second, our study showed that affective commitment was an important mediating mechanism in the relationship of inclusive leadership and follower taking charge. Drawing on social identity theory,26 inclusive leadership could boost followers’ affective commitment, which could enhance followers taking charge in turn. In addition, our research also responds to Randel et al39 call to explore and empirically explore the impact of inclusive leadership on employee behavior outcomes from the perspective of social identity theory.

Third, our research indicated the indirect relationship between inclusive leadership and follower taking charge via affective commitment was conditional on traditionality. Affective commitment has a greater impact on follower taking charge when the follower has a low traditionality. Meanwhile, we have explored the contextual boundary conditions between the relationship of the inclusive leadership and follower taking charge. Therefore, our study not only theoretically explored the interaction effect of affective commitment and traditionality on follower taking charge but also empirically explored the moderating role of traditionality in the relationship between affective commitment and follower taking charge, which response to calls for “the combined influence of individual factors and the organizational context”.6,23

Practical Implications

We also offer some practical suggestions. Firstly, our findings show that managers need to create an open and inclusive working environment and team climate through the implementation of inclusive leadership, care about employee needs, provide readily available support and help, and give employees opportunities and ways to express their opinions and suggestions, so as to reduce employees’ anxiety and concerns and improve follower’s taking charge.

Secondly, the most important reason why followers engage in taking charge is that they agree with and attach to the organizational values. Therefore, managers should attach great importance to the improvement and improvement of followers’ affective commitment. For example, we should improve the salary and welfare of followers, formulate a scientific, and personalized development path for followers, establish a shared, inclusive and progressive corporate values, and so on. So as to enhance the employee’s attachment to the organization from the spiritual aspects.

Finally, managers need to pay attention to the differences in followers’ values. In the Chinese context, the relationship of “keep one’s nose clean” and hierarchy is rooted in traditional Chinese thinking. Employees may have a certain ideological burden on making taking charge. Managers need equal two-way communication with employees to weaken the relationship between leaders and followers, reduce the traditionality with employees, and create a climate of inclusive for failure to encourage employees to dare to take risks and innovate, so as to reduce employees’ concerns about taking charge by reducing followers’ traditionality.

Limitations and Future Research

As with any study, our research also has several limitations. First, in the interaction with employees, the accessibility, interactive, fair, and fault-tolerant of inclusive leadership may have different effects, but this study only discusses the comprehensive impact of inclusive leadership behavior. In the future, inclusive leadership can be deeply explored the three internal dimensions affect the affective commitment and taking charge to further understand the mechanism of inclusive leadership.

Second, it takes a certain amount of time for employees to generate affective commitment to the organization. Therefore, the influence of inclusive leadership on affective commitment and the mediating role of affective commitment has a certain time span, although the three time points collections in this study used paired collection and multiple source methods to reduce CMV, it is still not a longitudinal study. Further research can try to track the relationship between causal variables and add case studies, situational experimental research, or multi-source mutual evaluation based on empirical research.

Third, although our research explored the influence of leadership style on taking charge from the perspective of emotion, in the real work scene, cognition, and emotion work together, sometimes even both. It is difficult to systematically explain the influence of situational factors on follower taking charge only from the perspective of cognition or emotion. Therefore, future research can combine cognitive and emotional dimensions to explore the effect of situational factors on follower taking charge.

Finally, based on Chinese Confucian ethical values, our study analyzes the variable “traditionality” reflecting the characteristics of Chinese native culture as a moderating variable. However, considering the differences between Chinese and Western cultures, employees in the Western cultural background mainly show strong modernity values, future research can collect sample data in the context of Western culture for comparative analysis to further test the scope of adaptation of the research conclusions of this article.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71672084, 71673135, 71974096), the Social Science Foundation of Jiangsu province of China (No. 20GLC012), the Policy Guidance Program of Science and Technology Department of Jiangsu Province of China (No. BR2020082).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Crant JM. Proactive behavior in organizations. J Manage. 2000;26(3):435–462. doi:10.1177/014920630002600304

2. Fuller J

3. Mcallister DJ, Dishan K, Elizabeth Wolfe M, Turban DB. Disentangling role perceptions: how perceived role breadth, discretion, instrumentality, and efficacy relate to helping and taking charge. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(5):1200–1211.

4. Burnett MF, Chiaburu DS, Shapiro DL, Li N. Revisiting how and when perceived organizational support enhances taking charge: an inverted U-shaped perspective. J Manage. 2015;41(7):1805–1826.

5. Li R, Zhang ZY, Tian XM. Can self‐sacrificial leadership promote subordinate taking charge? The mediating role of organizational identification and the moderating role of risk aversion. J Organ Behav. 2016;37(5):758–781.

6. Morrison EW, Phelps CC. Taking charge at work: extrarole efforts to initiate workplace change. Acad Manage J. 1999;42(4):403–419.

7. Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J Organ Behav. 2006;27(7):941–966.

8. Abraham Carmelia* RR-P, Zivc E. Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: the mediating role of psychological safety. Creat Res J. 2010;22(3):250–260.

9. Chen ZX, Tsui AS, Farh J-L. Loyalty to supervisor vs. organizational commitment: relationships to employee performance in China. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2002.

10. Choi SB, Tran TBH, Kang SW. Inclusive leadership and employee well-being: the mediating role of person-job fit. J Happiness Stud. 2017;18(6):1–25.

11. Ye Q, Wang D, Li X. Inclusive leadership and employees’ learning from errors: a moderated mediation model. Austr J Manage. 2018.

12. Ye Q, Wang D, Guo W. Inclusive leadership and team innovation: the role of team voice and performance pressure. Eur Manage j. 2019;37(4):468–480.

13. Zhu J, Xu S, Zhang B. The paradoxical effect of inclusive leadership on subordinates’ creativity. Front Psychol. 2020;10:2960.

14. Basharat J, Iqra A, Adeel Z, et al. Inclusive leadership and innovative work behavior: the role of psychological empowerment. J Manage Organ. 2018;1–18.

15. Qi L, Liu B, Wei X, Hu Y, Griep Y. Impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behavior: perceived organizational support as a mediator. PLoS One. 2019;14:2.

16. Carmeli A, Reiter-Palmon R, Ziv E. Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: the mediating role of psychological safety. Creat Res J. 2010;22(3):250–260.

17. Hanh Tran TB, Choi SB. Effects of inclusive leadership on organizational citizenship behavior: the mediating roles of organizational justice and learning culture. J Pac Rim Psychol. 2019;13:e17.

18. Ning L, Dan SC, Kirkman BL, Xie Z. Spotlight on the followers: an examination of moderators of relationships between transformational leadership and subordinates’ citizenship and taking charge. Pers Psychol. 2013;66(1):225–260.

19. Li SL, He W, Kai CY, Long LR. When and why empowering leadership increases followers’ taking charge: a multilevel examination in China. Asia Pac J Manage. 2015;32(3):645–670.

20. Li J, Furst-Holloway S, Gales L, Masterson SS, Blume BD. Not all transformational leadership behaviors are equal: the impact of followers’ identification with leader and modernity on taking charge. J Leadership Organ Stud. 2017;24(3):318–334.

21. Zhang W, Liu W. Leader humility and taking charge: the role of OBSE and leader prototypicality. Front Psychol. 2019;10.

22. Wang Q, Zhou X, Bao J, Zhang X, Ju W. How is ethical leadership linked to subordinate taking charge? A moderated mediation model of social exchange and power distance. Front Psychol. 2020;11.

23. Zeng H, Zhao L, Zhao Y. Inclusive leadership and taking-charge behavior: roles of psychological safety and thriving at work. Front Psychol. 2020;11:62.

24. Ribeiro P, Manuel N, Coelho M, Fernandes A, Semedo D, Suzete A. Effects of authentic leadership, affective commitment and job resourcefulness on employees’ creativity and individual performance. Leadership Organ Develop j. 2016.

25. Ribeiro N, Duarte AP, Filipe R, Oliveira RT. How authentic leadership promotes individual creativity: the mediating role of affective commitment. J Leadership Organ Stud. 2020;27(2):189–202.

26. Tajfel H, Turner J. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Soc Psychol Intergroup Rel. 1979;33:94–109.

27. van Daan K, Michael H, A social identity model of leadership effectiveness in organizations. Res Organ . 2003.

28. Farooq O, Payaud M, Merunka D, Valette-Florence P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. J Business Ethics. 2014;125(4):563–580.

29. Kobulnicky PJ. Commitment in the workplace: theory, research and application. J Acad Librarianship. 1997;24(2):175.

30. Kazemipour F, Mohd Amin S. The impact of workplace spirituality dimensions on organisational citizenship behaviour among nurses with the mediating effect of affective organisational commitment. J Nurs Manag. 2012;20(8):1039–1048.

31. Diedericks E, Rothmann S. Flourishing of information technology professionals: effects on individual and organisational outcomes. South Afr J Bus Manage. 2014;45(1):27–41.

32. Farh J-L, Hackett RD, Liang J. Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support–employee outcome relationships in China: comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Acad Manage J. 2007;50(3):715–729.

33. Lin W, Ma J, Zhang Q, Li JC, Jiang F. How is benevolent leadership linked to employee creativity? The mediating role of leader–member exchange and the moderating role of power distance orientation. J Business Ethics. 2018;152(4):1099–1115.

34. Guo Y, Zhu Y, Zhang L. Inclusive leadership, leader identification and employee voice behavior: the moderating role of power distance. Curr Psychol. 2020.

35. Li S-L, Huo Y, Long L-R. Chinese traditionality matters: effects of differentiated empowering leadership on followers’ trust in leaders and work outcomes. J Business Ethics. 2017;145(1):81–93.

36. Yao Z, Zhang X, Liu Z, Zhang L, Luo J. Narcissistic leadership and voice behavior: the role of job stress, traditionality, and trust in leaders. Chin Manage Stud. 2019.

37. Zhao H. Relative leader-member exchange and employee voice: mediating role of affective commitment and moderating role of Chinese traditionality. Chin Manage Stud. 2014;8(1):27–40.

38. Juma N, Lee J-Y. The moderating effects of traditionality–modernity on the effects of internal labor market beliefs on employee affective commitment and their turnover intention. Int J Human Res Manage. 2012;23(11):2315–2332.

39. Randel AE, Galvin BM, Shore LM, et al. Inclusive leadership: realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Human Res Manage Rev. 2018;28(2):190–203.

40. Temple JB, Ylitalo J. Promoting inclusive (and Dialogic) leadership in higher education institutions. Tertiary Educ Manage. 2009;15(3):277–289.

41. Ingrid MN, Amy CE. Making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J Organ Behav. 2006;27(7):941.

42. Dvir T, Eden D, Avolio BJ, Shamir B. Impact of transformational leadership on follower development and performance: a field experiment. Acad Manage J. 2002;45(4):735–744.

43. Srivastava A, Bartol KM, Locke EA. Empowering leadership in management teams: effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance. Acad Manage J. 2006;49(6):1239–1251.

44. Ehrhart MG. Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit-level organizational citizenship behavior. 2004;57(1):61–94.

45. Allen N, Meyer J, Measurement T. Antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J Occupational Psychol. 1990;63.

46. Meyer JP, Allen NJ. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Res Manage Rev. 1991;1(1):61–89.

47. Li Z, Duverger P, Yu L. Employee creativity trumps supervisor-subordinate guanxi: predicting prequitting behaviors in China’s hotel industry. Tourism Manage. 2018;69:23–37.

48. Asif M, Miao Q, Jameel A, Manzoor F, Hussain A. How ethical leadership influence employee creativity: a parallel multiple mediation model. Curr Psychol. 2020.

49. Yogalakshmi JA, Suganthi L. Impact of perceived organizational support and psychological empowerment on affective commitment: mediation role of individual career self-management. Curr Psychol. 2020;39(3):885.

50. Hirak R, Peng AC, Carmeli A, Schaubroeck JM. Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: the importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. Leadership Quar. 2012;23(1):107–117.

51. Hantula A, Inclusive Leadership: D. The essential leader-follower relationship. Psychol Record. 2009;59(4):701–704.

52. Shore LM, Randel AE, Chung BG, Dean MA, Ehrhart KH, Singh G. Inclusion and diversity in work groups: a review and model for future research. J Manage. 2011;37(4):1262–1289.

53. Fang Y-C, Chen J-Y, Wang M-J, Chen C-Y. The impact of inclusive leadership on employees’ innovative behaviors: the mediation of psychological capital. Front Psychol. 2019;10.

54. Kim TY, Liu Z, Diefendorff JM. Leader–member exchange and job performance: the effects of taking charge and organizational tenure. J Organ Behav. 2015;36(2):216–231.

55. Grant AM, Ashford SJ. The dynamics of proactivity at work. Res Organ Behav. 2008;28(28):3–34.

56. Parker SK, Collins CG. Taking stock: integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. J Manage. 2010;36(3):633–662.

57. Dan SC, Lorinkova NM, Dyne LV. Employees’ social context and change-oriented citizenship a meta-analysis of leader, coworker, and organizational influences. Group Organ Manage. 2013;38(3):291–333.

58. Tajfel H. Social psychology of intergroup relations. Ann Rev Psychol. 1982.

59. Hogg MA, Terry DJ. Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Acad Manage Rev. 2000.

60. Mael F, Ashforth BE. Alumni and their alma mater: a partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J Organ Behav. 1992;13(2):103–123.

61. Javed B, Karim A, Samina K. Quratulain, inclusive leadership and innovative work behavior: examination of LMX perspective in small capitalized textile firms. J Psychol. 2018.

62. Wang Q, Weng Q, Mcelroy JC, Ashkanasy NM, Lievens F. Organizational career growth and subsequent voice behavior: the role of affective commitment and gender. J Vocat Behav. 2014;84(3):431–441.

63. Hui C, Lee C, Rousseau DM. Psychological contract and organizational citizenship behavior in china: investigating generalizability and instrumentality. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89(2):311–321.

64. Farh J-L, Earley PC, Lin S-C. Impetus for action: a cultural analysis of justice and organizational citizenship behavior in chinese society. Adm Sci Q. 1997;42.

65. Zhen XC, Aryee S. Delegation and employee work outcomes: an examination of the cultural context of mediating processes In China. Acad Manage J. 2007;50:1.

66. Li H, Ngo HY. Chinese traditionality and career success: mediating roles of procedural justice and job insecurit. Acad Manage Ann Meeting Proc. 2014;2014(1):15170.

67. Zhang AY, Song LJ, Tsui AS, Fu PP. Employee responses to employment-relationship practices: the role of psychological empowerment and traditionality. J Organ Behav. 2014;35(6):809–830.

68. Hu C, Baranik LE, Cheng Y-N, Huang J-C, Yang -C-C. Mentoring support and protégé creativity: examining the moderating roles of job dissatisfaction and Chinese traditionality. Asia Pac J Human Res. 2020;58(3):335–355.

69. Guan P, Capezio A, Restubog SLD, Read S, Lajom JAL, Li M. The role of traditionality in the relationships among parental support, career decision-making self-efficacy and career adaptability. J Vocat Behav. 2016;94:114–123.

70. Wang HJ, Lu CQ, Lu L. Do people with traditional values suffer more from job insecurity? The moderating effects of traditionality. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2012;23(1):1–11.

71. Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Podsakoff NP. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Ann Rev Psychol. 2012;63(1):539.

72. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903.

73. Brislin RW. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. Methodology. 1980;389–444.

74. Meyer JP, Allen NJ, Smith CA. Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Human Res Manage Rev. 1993;78(1):61–89.

75. Zhen XC, Francesco AM. The relationship between the three components of commitment and employee performance in China. J Vocat Behav. 2003;62(3):490–510.

76. Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL. Multivariate Data Analysis. Prentice hall Upper Saddle River, NJ; 1998:5.

77. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. J Educ Measurement. 2013;51(3):335–337.

78. Dawson JF. Moderation in management research: what, why, when, and how. J Bus Psychol. 2014;29(1):1–19.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.