Back to Journals » Journal of Healthcare Leadership » Volume 13

How Can We Raise Awareness of Physician’s Needs in Order to Increase Adherence to Management and Leadership Training?

Authors Voirol C , Pelland MF, Lajeunesse J, Pelletier J, Duplain R, Dubois J, Lachance S, Lambert C , Sader J , Audetat MC

Received 13 November 2020

Accepted for publication 3 March 2021

Published 28 April 2021 Volume 2021:13 Pages 109—117

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S288199

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Russell Taichman

Christian Voirol, 1– 3 Marie-France Pelland, 2 Julie Lajeunesse, 2 Jean Pelletier, 2 Rejean Duplain, 4 Josee Dubois, 5 Silvy Lachance, 6 Carole Lambert, 5 Julia Sader, 7 Marie-Claude Audetat 2, 7, 8

1Haute Ecole Arc Santé, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Neuchâtel, Switzerland; 2Département de Médecine Familiale et de Médecine d’urgence, Faculté de Médecine, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada; 3Département de Psychologie, Faculté des Arts et des Sciences, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada; 4Academic Support, Campus de l’Université de Montréal en Mauricie, Trois-Rivières, Québec, Canada; 5Département de Radiologie, Radio-Oncologie et Médecine Nucléaire, Faculté de Médecine, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada; 6Département de Médecine, Faculté de Médecine, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada; 7Unité de Développement et de Recherche en Éducation Médicale (UDREM), Faculté de Médecine, Université de Genève, Genève, Switzerland; 8Institut Universitaire de Médecine de Famille et de l’Enfance (IuMFE), Faculté de Médecine, Université de Genève, Genève, Switzerland

Correspondence: Christian Voirol

HE-Arc Santé, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Espace de l’Europe 11, Neuchâtel, 2000, Suisse

Tel +41 32 930 2554

Fax +41 32 930 1213

Email [email protected]

Abstract: Due to the increasing complexity of medical education and practice, the training of healthcare professionals for leadership and management roles and responsibilities has become increasingly important. But gaps in physician leadership and management skills have been identified across a broad range of organizational and geographic settings. Many clinicians are inadequately prepared to meet their day-to-day clinical leadership responsibilities. Simultaneously, physicians’ leadership and management skills play a central role and yield superior outcomes for patients and health care delivery organizations. Currently, there is a tremendous variability in the amount of time, structure and resources dedicated to leadership/management training for physicians. Physicians who have completed such trainings seem to be pleased with the outcome. However, only a limited number of physicians enroll in these types of trainings. Several reasons can explain this fact, but it seems crucial to investigate what could increase the involvement of medical leaders and managers in these training programs. This paper offers a framework for addressing the barriers to training commitment and for designing initial training interventions for physicians. This framework is rooted in two well-known theoretical models used in social sciences. It aims to promote self-assessed knowledge and expertise amongst physicians about to embrace leader/manager careers. By developing the ability to explore and be curious about one’s own experience and actions, physicians may suddenly open up the possibilities of purposeful learning. The process we describe in this paper may be an essential step in fostering the involvement of physicians in leadership and management training processes. And this is essential to contribute to the advancement of medical discipline.

Keywords: insight, self-consciousness, career path, assessment, training commitment, management, physicians, leadership

High-quality care requires that clinicians work within and manage different teams, incorporate complex technologies and therapeutics, and simultaneously... manage the care of an abundance of patients.1–3 Due to the increasing complexity of medical education and practice, the training of healthcare professionals for leadership and management roles and responsibilities has become increasingly important.4–6 In this perspective, physician leadership and management development programs typically aim to develop physicians’ leadership competencies and improve organizational performance.7

Navigating the Spectrum of Leadership and Management

Leadership and management are closely interrelated processes, and both are essential for organizations to strategically accomplish key objectives. Leadership may be defined as the ability to present compelling visions and goals in order to motivate and bring about change, while management involves achieving specific results through planning, organizing, and solving problems.7,8 In practice, the distinctions between leadership and management is rarely clear-cut. Indeed, leaders often find themselves moving quickly between management and leadership roles. Whether it is leadership or managerial skills, most physicians have to deal with both. Thus, leading and managing fall on a broad spectrum of complementary, and mutually dependent behaviors.9

The CanMEDS Physician Competency Framework10 is the most widely accepted and widely applied physician competency framework around the world. It identifies and describes seven roles for physicians: medical expert, communicator, collaborator, manager, health advocate, scholar, and professional.10 The primary target audiences comprise trainees, front-line teachers, program directors of various curricula and clinician educators who design programs.

The CanMEDS Leader/Manager Role describes the commitment of all physicians:

“As a societal expectation, physicians demonstrate collaborative leadership and management within the health care system. At a system level, physicians contribute to the development and delivery of continuously improving health care and engage with others in working toward this focus to the patient. Physicians integrate their personal lives with their clinical, administrative, scholarly, and teaching responsibilities. They function as individual care providers, as members of teams, and as participants and leaders in the health care system locally, regionally, nationally, and globally ”.10,11

In addition, the growing importance of collaborative practices,12 interdisciplinarity13 and integration of the patient partner into care teams14 also requires leadership and management skills.

Challenge Ahead

Gaps in physician leadership and management skills have been identified across a broad range of organizational and geographic settings. Many clinicians are inadequately prepared to meet their day-to-day clinical leadership responsibilities. Simultaneously, evidence highlights that physicians’ leadership and management skills plays a central role and yield superior outcomes for patients and health care delivery organizations.15–22

Many Trainings to Choose from

Currently, there is a tremendous variability in the amount of time, structure and resources dedicated to leadership/management training for physicians.7 Two distinct ways of leadership/management development are depicted in the literature. The first is training leaders throughout initial medical education, while the second consists in ongoing training for physicians later in their career.23 The majority of these interventions include workshops, short courses, fellowships, and other longitudinal programs.24–26 Surprisingly, only a few of residency programs provide formally structured, evidence-based leadership and management training for all residents.27 In addition, although self-awareness seems to be fundamental to leadership/management capacity, relatively few programs addressed personal growth and self-awareness.9 Research results have highlighted the main benefits of faculty development interventions designed to improve leadership/management abilities.24 These are:

- High satisfaction: Consistently participants found programs to be valuable both personally and professionally.

- A change in attitudes toward leadership/management roles and organizational contexts: Participants report a favorable change in their own perception towards their leadership/management abilities and organizations skills.

- Improvements in knowledge and skills: Participants report improved knowledge of leadership/management principles, concepts and strategies.

- Shifts in leadership/management behavior: Self-perceived shifts in leadership/management behavior are steadily reported and consist mainly of a change in leadership/management styles and the implementation of newly acquired skills in the workplace.24

Major Challenge: Motivating Physicians to Attend Trainings

Physicians who have completed such trainings seem to be pleased with the outcome. However, only a limited number of physicians enroll in these types of trainings. Several reasons can explain this fact: external ones, such as lack of protected time, lack of senior manager support or lack of perceived value by the organization, may dissuade physicians from enrolling. Individual reasons, such as physicians’ skepticism about the need to develop their own leadership/management abilities also contributes to the lack of training. In addition, most physicians value autonomy and often perceive training interventions as a threat to their independence.28 Moreover, many clinicians perceive an inherent tension between managing care and providing it. This wariness of managerial work seems to be deeply rooted in medical culture.29

Clinicians also worry that leadership/management skills development will be overly time-consuming and will detract from opportunities to improve their clinical proficiency, rather than enabling them to improve their performance and achieve better outcomes. In addition, physicians may be unaware of the validity of leadership/management studies because of the use of different methodologies.30

Finally, health care organizations rarely identify or reward frontline leaders who can serve as role models for younger clinicians, missing critical opportunities to explicitly acknowledge their importance in medical training and making it difficult for formal leadership/management development program to take place.31

Even if we can imagine that physicians may be motivated to take on manager/leader positions, driven by idealism, frustration with existing problems, or belief that system improvement is at least as important as medical knowledge to help people, previous research have shown that most physicians do not engage in such responsibilities with a career plan.

They rather seize opportunities, or are approached by colleagues who encourage them to take on leadership/management positions.32 They usually have no training, prior to taking on such positions because they do not identify the difference between medical leadership and managerial one and the different skills involved. They seldom recognize the abilities and expertise they need to undertake leadership/management position.32–35

This situation led physicians potentially into difficult situations, in terms of time and conflict management,36 stress37 or burnout.38 This is not surprising, given that it has been shown that beginners in a field (or novices) have lower metacognitive awareness than experts. This unawareness leads them to be less sensitive to task demands (eg, time, effort, resources needed), less strategic and less flexible in planning and problem solving.39 Despite all this, physicians assessment of their needs is not often studied and their self-assessment is not promoted.5

It therefore seems crucial to investigate what physicians need to develop effective leadership and management competences. It will then be possible to provide early support by establishing competences required for their career path (including a training program). This seems to be one of the prerequisites in motivating the involvement of the next generation of medical leaders and managers.22,40

Aim of This Paper

This paper offers a framework for addressing the barriers to training commitment and for designing training interventions for physicians. This conceptual framework is rooted in the literature; demonstrating its relevance and ability to mitigate these barriers and is the core of a training program implemented over the past 8 years for leading teachers at the Faculty of Medicine of the Université de Montréal.

A Conceptual Framework to Increase Physicians’ Adherence to Management and Leadership

Two well-known theoretical models rooted in social sciences are at the base of our framework: Herbart’s four-step method of learning41 and Johari’s window of Luft & Ingham.42 The following paragraphs will describe these two models.

The Learning Steps Model

This framework has been an inspiration to many authors.41,43 The first description of this four steps model of learning is ascribed to Johann Friedrich Herbart (1776–1841)44,45 and consists of the following procedures: “(1) preparation; (2) presentation; (3) application; (4) follow-up”.

The (1) preparation step is about the “necessity to prepare the trainee to learn new facts or ideas and to establish a teaching base. This is done by first discovering what the trainee already knows about the course and then explaining logically its aims, content, and methodology. By doing so, the trainee will know exactly what to expect of the trainer and what the latter will expect of him. Finally, it is needful to arouse the interest, attention, and motivation of the trainee. By whatever means possible, the trainer must get the trainee to see “what’s in it for him.”46

Step (2) presentation consists in the transmission by the teacher of the contents necessary to the learner for the implementation which is carried out in step (3) application. In reality, the learning process follows an ascending curve and is usually carried out by alternating knowledge acquisition, practical application and reflexive analysis of this application. Finally, step (4) follow-up consists of a longitudinal follow-up of the learner’s learning.

This four steps model of learning and its developments are often cited in the literature in medical education or leadership/management as a learning process.47–49 In the scientific literature, the focus is usually on steps (2), (3) and (4), ie teaching and transmission of knowledge, implementation and possibly monitoring of the acquisition and integration process. However, before attempting to convey the content, it is necessary to ensure that the future learner is indeed aware of his or her shortcomings, is interested in developing skills and is mobilized to adopt a learner’s posture.

Howell deepened Herbart’s steps by introducing the concept of stages of competence which can be either conscious or unconscious.50 As shown in Figure 1, the first stage, characterized by an “Unconscious incompetence” is a stage “where you are not even aware that you do not have a particular competence”50 (pp29–33). In our context, the first stage aims to support the development of physician’s metacognitive skills and reflection, so they can become more conscious about their willingness and ability to engage in specific leadership or management task and responsibilities. Thus, while this first stage is of major importance, it is however very often overlooked, which is one of the reasons, in our opinion, for the lack of interest of physicians to train in this field.

|

Figure 1 The four-step model of learning associated with the Johari window model: importance of step “(1) Preparation”: making conscious what is still unconscious. |

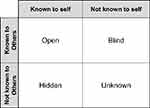

The Johari Window Model

The Johari window model was proposed by JOseph Luft & and HARRIngton Ingham precisely in order to clarify the issues related to self-knowledge.42 As shown in Figure 2, this model presents on one axis (horizontally) what the person knows or does not know about oneself. The vertical axis highlights what people know or do not know about what characterizes the other person. What the person knows about oneself and what others also know is called the Open area. What the person knows about oneself but what others do not know is the Hidden area. What others know about the person but that the person ignore is the Blind area. Finally, what no one knows is in the Unknown area. The unknown and blind areas may contain unconscious contents.

|

Figure 2 The Johari window model. |

In the context of leadership/management learning, the main objective is therefore to enable participants to maximize the transfer of content from the Unknown and Blind areas to the Hidden and Open areas through a reflective process. Reflection is an active process of witnessing one’s own experience in order to explore it in greater depth.51 This represents nevertheless a challenging task, requiring commitment and willingness to reveal oneself, which is only possible in a safe learning environment.

A Conceptual Framework

The combination of these two models presented above provides us an interesting framework, as described in Figure 1, to respond to the challenge of engaging physicians in a leadership training process.

First, emphasis is placed on the dynamic and progressive process the learner goes through, moving from Unconscious incompetence, via Conscious incompetence, than Conscious competence, to Unconscious competence.52 In the first step, learners are unaware of what they do not know; they must recognize their own incompetence, and the value of the new competences to acquire, before moving on to the next step. Information, insights, and reflective processes are keys to make them progress to the second step, conscious incompetence; in this step, learners become aware of their limited competences. Quality of training is crucial during this stage. In the third step, Conscious competence, learners have gained significant competences (skills, knowledge, and attitudes), but each step requires deliberate thought and action. Over time and with experience, learners move into the fourth step, Unconscious competence, in which they function more instinctively with less deliberate attention.

As said before, most of the leadership and management training offered are already in steps 2, 3 and 4 of the learning model. The teaching is part of step “(2) presentation” and its implementation is in part “(3) application”. But the first step “(1) preparation”, allowing to move from “Unconscious incompetence” to “Conscious incompetence”, is of major importance: it focuses on preparing the learner by identifying their prior competences about leadership/management, and the ones which might be lacking. This is especially crucial for leadership and management, which requires much more than the sole acquisition of knowledge or skills. Indeed, being a good leader or manager is about self-awareness and self-actualization in various demanding and often complex organizational contexts.53 Therefore, this first phase becomes not only an evaluation of what the participants know about leadership/management, but also and above all, an evaluation of what they know about themselves as a leader/manager in their work environment. Often, they simply do not see themselves as potential leader/managers. This is why, year after year, we solicit senior managers to identify and suggest the names of junior colleagues who, in their opinion, have a lot of potential (in order to encourage a certain mix while remaining clearly disciplinary, participants have always been chosen amongst specialists and family physicians. In addition, a minimum of 5 years of experience as a clinician and, if possible, experience as a leader/manager were also recommended). So, we discovered that it is rather prior to the training that the focus must be made in order to raise the interest of physicians to partake in a training in leadership and management. Indeed, we observed that the main problem with their engagement lies not only in physicians’ lack of knowledge of their leadership/management skills or inabilities, but also in their unawareness of what is really needed to be effective leaders/managers. In this perspective, the first step of our framework, as described in Figure 1, is therefore crucial: the aim is to support physicians to develop metacognitive skills and reflection, so they can become more conscious about their willingness and ability to engage in specific leadership or management task and responsibilities.

Our Five-Days Program

We have set up an initial training program called “Relève Leadership” that has been taking place since 2012 at a rate of two groups of 10 physicians per year. This training program is given over five days during a period of 12 months. The objectives of this training program are to enable participants to 1) develop a clear vision of the competences required to take on leadership/management responsibilities which might be of interest to them, 2) evaluate where they stand in regard to the main skills required and, where they can be applied to, 3) design a training/development plan that will enable them to acquire the skills required over the next few years.

This program is structured in four phases. During the first phase, the contents explored are those relating to the basic skills, knowledge and attitudes required for leadership and management. In the absence of training in the field, physicians are often unaware of basic contents such as conflict management, definition of roles and responsibilities, time management, implementation of change, etc. This can lead them to underestimate or overestimate these contents. This is the step I shown in Figure 3.

|

Figure 3 The training process of “Relève Leadership”. |

The second phase is designed to allow participants to scientifically evaluate their own management and leadership skills, competencies, and knowledge. They fill out questionnaires and receive a detailed analysis of their profile, specifying their strengths and areas for improvement and exploring their blind or unknown areas. Even more than those mentioned above, it is the available potential that needs to be investigated. In fact, it is a question of identifying which competencies are already available and which ones need to be developed. This is the step II shown in Figure 3.

Thirdly, the blind zone to be explored consists of identifying the gap between the skills available and those required. The participants are led to analyze leadership/management situations, make links with their personal profiles and get involved in role-playing. These activities aim to enable them to identify how their skills, scientifically assessed at the beginning of the program, may be applied in their day-to-day practice. Through leadership/management case discussions and individual and collective reflexive approaches, training needs are clarifying as well. It is also often about dismantling the belief that management and leadership skills are innate and cannot be developed. This is the step III indicated in the Figure 3.

Once the required competencies have been identified, the available skills have been assessed, and physicians are convinced that leadership/management skills can be developed, participants must develop an action plan (objectives, means, conditions, etc.) aimed at acquiring the competencies lacking or to be improved. This is the step IV indicated in Figure 3.

At the end of this process, physicians are much more aware about their motives for engaging in management and leadership trainings. They also are more able to make an informed decision about their career plan and the goals they set out during training.

Because the unveiling process requires a high level of trust in the group, a very specific setup is put in place. This setup (confidentiality, mandatory attendance every 5 days, verbalization of one’s experience, maximum of 10 participants per group, minimum 5 years of experience, mixed specialist, and family physicians, etc.) is inspired more by personal growth and self-awareness workshops than by training ones. The group dynamic creates a strong sense of belonging. And this sense of belonging contributes to the organization, year after year, of supervisory meetings and follow-up. These meetings, bringing together participants from different class years and applying a similar setup, promote the continuous training of participants.

Discussion

How may this conceptual framework be useful? According to the literature,7 our conceptual framework aims to promote self-assessed knowledge and expertise amongst physicians about to embrace leader/manager careers. By developing the ability to explore and be curious about one’s own experience and actions, physicians may suddenly open up the possibilities of purposeful learning. High-quality health care relies on teams, collaboration, and interdisciplinary work, and physician’s leadership is crucial for optimizing health system and organization’s performance.54–56 But even if we do believe that physicians have everything to gain by developing their skills within multidisciplinary teams, bridging professional boundaries, and strengthening networks,57 our previous training program is for physicians only, considering that it may facilitate open dialogue amongst peers and encourage the disclosure of potential weaknesses through examples specific to the medical profession.58

The different steps of this program and the interactive learning and feedback fosters the development of self-awareness on the importance of identifying one’s own strengths, weaknesses and knowledge required to become a leader, thus favoring more appropriate careers choices. We also want to give our participants the opportunity to reflect on personal goals and objectives, as well as to discover the benefits of exchanging information and ideas with peers.

Conclusion

Many different avenues for future leadership and management training development have already been identified: training development programs for pre- and post-graduated education should: ground their work in a theoretical framework; articulate their definition of leadership and management, and explore the value of extended programs and follow-up sessions to get their objectives in a structured planning.24

The process we have described is, in our opinion, an essential step in fostering the involvement of physicians in leadership and management training processes. And this is essential to contribute to the advancement of medical discipline. An upcoming article of our research team will present the evaluation results of our training program which has been in place for the past 8 years, the achievement of its objectives, (its short-, medium- and long-term impacts) and finally the potential success actors and remaining challenges. We believe that this conceptual framework can be useful to better prepare decision-makers in both health care institutions and medical schools.

Previous Presentations

This conceptual model has not yet been presented elsewhere.

Ethical Approval

This research is part of a research project approved by the Health Research Ethics Board (CERES) at the University of Montreal (certificate #12-045-CERES-D) issued on May 24, 2012.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prof. Raynald Gareau, University of Trois-Rivières, Québec, which is now retired for several years and was an important contributor to the genesis of this work. Also, the authors would like to thank all the participants of the various training workshops that took place at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Montreal; their involvement and comments provided valuable insights and contributed to the success of the project.

Funding

This research was supported in part by grants from the Chaire Sadok Besrour in family medicine of the Université de Montréal grant programs.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Armstrong PW. A time for transformative leadership in academic health sciences. Clin Investig Med. 2007;30(3):127–132. doi:10.25011/cim.v30i3.1081

2. Souba W, Mauger D, Day D. Does agreement on institutional values and leadership issues between deans and surgery chairs predict their institutions’ performance? Acad Med. 2007;82(3):272–280. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180307e14

3. Souba W. Perspective: a new model of leadership performance in health care. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1241–1252. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c0385

4. Zaher CA. Physician leadership. Learning to be a leader. Physician Exec. 1996;22(9):10–17.

5. Collins-Nakai R. Leadership in medicine. Mcgill J Med. 2006;9(1):68–73.

6. Stoller J. Developing Physician-Leaders: a Call to Action. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(7):876–878. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1007-8

7. Frich JC, Brewster AL, Cherlin EJ, Bradley EH. Leadership Development Programs for Physicians: a Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):656–674. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3141-1

8. Yukl GA. Leadership in Organizations.

9. Collins DB, Holton III EF. The Effectiveness of Managerial Leadership Development Programs: a Meta-Analysis of Studies from 1982 to 2001. Hum Resour Dev Q. 2004;15(2):217–248. doi:10.1002/hrdq.1099

10. Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J; Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. CanMEDS 2015 - Physician Competency Framework. Ottawa (Ontario), Canada: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015. http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/canmeds/resources/publications.

11. Danilewitz M, McLean L. A landscape analysis of leadership training in postgraduate medical education training programs at the University of Ottawa. Can Med Educ J. 2016;7(2):e32–e50. doi:10.36834/cmej.36645

12. Mertens F, de Groot E, Meijer L, et al. Workplace learning through collaboration in primary healthcare: a BEME realist review of what works, for whom and in what circumstances: BEME Guide No. 46. Med Teach. 2018;40(2):117–134. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2017.1390216

13. van Gessel E, Picchiottino P, Doureradjam R, Nendaz M, Mèche P. Interprofessional training: start with the youngest! A program for undergraduate healthcare students in Geneva, Switzerland. Med Teach. 2018;40(6):595–599. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1445207

14. Pomey M, Efanov JI, Arsenault J, et al. The Partnership Co-Design Lab: co-constructing a Patient Advisor Programme to increase adherence to rehabilitation after upper extremity replantation. J Health Design. 2018:94–101. doi:10.21853/JHD.2018.47

15. Squires M, Tourangeau A, Spence Laschinger HK, Doran D. The link between leadership and safety outcomes in hospitals. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18(8):914–925. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01181.x

16. Weberg D. Transformational Leadership and Staff Retention. Nurs Adm Q. 2010;34(3):246–258. doi:10.1097/naq.0b013e3181e70298

17. Wells R, Jinnett K, Alexander J, Lichtenstein R, Liu D, Zazzali JL. Team leadership and patient outcomes in US psychiatric treatment settings. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(8):1840–1852. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.060

18. Ham C. Improving the performance of health services: the role of clinical leadership. Lancet. 2003;361(9373):1978–1980. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13593-3

19. Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J Organ Behav. 2006;27(7):941–966. doi:10.1002/job.413

20. Majmudar A, Jain AK, Chaudry J, Schwartz RW. High-performance teams and the physician leader: an overview. J Surg Educ. 2010;67(4):205–209. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.06.002

21. Bohmer R. Designing Care: Aligning the Nature and Management of Health Care. Boston, USA: Harvard Business Press; 2009.

22. Health Association Nova Scotia. Leadership in Healthcare in Nova Scotia. Bedford, Nova Scotia: Health Association Nova Scotia; 2012. Available from: http://www.healthassociation.ns.ca/Generic.aspx?PAGE=Section+Our+Services/Research+and+Policy+Dev+Section/Decision+Support&portalName=base.

23. Comber S, Wilson L, Crawford KC. Developing Canadian physician: the quest for leadership effectiveness. Leadersh Heal Serv. 2016;29(3):282–299. doi:10.1108/LHS-10-2015-0032

24. Steinert Y, Naismith L, Mann K. Faculty development initiatives designed to promote leadership in medical education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 19. Med Teach. 2012;34(6):483–503. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.680937

25. Goldstein AO, Calleson D, Bearman R, Steiner BD, Frasier PY, Slatt L. Teaching Advanced Leadership Skills in Community Service (ALSCS) to Medical Students. Acad Med. 2009;84(6):754–764. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a40660

26. Fairchild DG, Benjamin EM, Gifford DR, Huot SJ. Physician Leadership: enhancing the Career Development of Academic Physician Administrators and Leaders. Acad Med. 2004;79(3):214–218. doi:10.1097/00001888-200403000-00004

27. Ackerly DC, Sangvai DG, Udayakumar K, et al. Training the next generation of physician-executives: an innovative residency pathway in management and leadership. Acad Med. 2011;86(5):575–579. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318212e51b

28. Blumenthal DM, Bernard K, Bohnen J, Bohmer R. Addressing the leadership gap in medicine: residents’ need for systematic leadership development training. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):513–522. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824a0c47

29. Davies HT, Harrison S. Education and debate Trends in doctor-manager relationships. Br Med J. 2003;646–649. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7390.646

30. Mountford J, Webb C. When clinicians lead. McKinsey Q. 2009;44–49.

31. Broadhurst S. Clinical leadership: bridging the divide. Int J Cult Ment Health. 2012;5(2):146–147. doi:10.1080/17542863.2010.512731

32. Voirol C, Audétat M-C, Pelland M-F, Lajeunesse J, Gareau R, Duplain R. Comment mieux aider les médecins de la relève à assumer des responsabilités de gestion? [How can better support be provided to the next generation of physicians taking on management responsibilities?]. Pédagogie Médicale. 2014;15(3):169–181. doi:10.1051/pmed/2014018

33. Chaudry J, Jain A, McKenzie S, Schwartz RW. Physician Leadership: the Competencies of Change. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(3):213–220. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2007.11.014

34. Clark J, Armit K. Leadership competency for doctors: a framework. Leadersh Heal Serv. 2010;23(2):115–129. doi:10.1108/17511871011040706

35. Fulop L, Day GE. From leader to leadership: clinician managers and where to next? Aust Heal Rev. 2010;34(3):344–351. doi:10.1071/AH09763

36. Romano M. Ready or not: talented, high-achieving physicians often come up short in the skills and other attributes needed to excel as CEO. Mod Healthc. 2004;34(17):26–34.

37. Agius RM, Blenkin H, Deary IJ, Zealley HE, Wood RA. Survey of perceived stress and work demands of consultant doctors. Occup Environ Med. 1996;53(4):217–224. doi:10.1136/oem.53.4.217

38. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–146. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004

39. Persky AM, Robinson JD. Moving from novice to expertise and its implications for instruction. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(9):72–80. doi:10.5688/ajpe6065

40. Sinclair DG, Carruthers C, Swettenham J. Healthcare and physician leadership. Healthc Q. 2011;14(1):6–8. doi:10.12927/hcq.2011.22148

41. De Phillips FA, Berliner WM, Cribbin JJ. Management of Training Programs. Homewood, Ill: R. D. Irwin; 1960.

42. Luft J, Ingham H. The Johari window, a graphic model of interpersonal awareness. Proc West Train Lab Gr Dev UCLA, Los Angeles. 1955;5(1):4.

43. Kolb D. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood-Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall; 1984.

44. Dunkel HB. Herbartianism Comes to America: part I. Hist Educ Q. 1969;9(2):202–233. doi:10.2307/367318

45. Saettler P. The Evolution of American Educational Technology. Greenwich, USA: Information Age Publishing; 2004.

46. De Phillips FA, Berliner WM, Cribbin JJ. The four-step method of instruction. In: Management of Training Programs. Homewood, Ill: R. D. Irwin; 1960:158–161.

47. Crandall SJ, George G, Marion GS, Davis S. Applying theory to the design of cultural competency training for medical students: a case study. Acad Med. 2003;78(6):588–594. doi:10.1097/00001888-200306000-00007

48. Cannon HM, Feinstein AH, Friesen DP. Managing complexity: applying the conscious-competence model to experiential learning. Dev Bus Simulations Exp Learn. 2010;37:172–182. doi:10.1590/S1413-85572004000200003

49. Howell W. Theoretical directions for intercultural communication. In: Asante M, Newmark E, Blake C, editors. Handbook of Intercultural Communication. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE; 1979:23–41.

50. Howell WS. The Empathic Communicator. Minnesota, USA: Wadsworth Publishing Company; 1982.

51. Amulya J. What is Reflective Practice? Center for Reflective Community Practice, ed; Boston, USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 2009. doi:10.4135/9781526402318.n1

52. Hansen A. Trainees and teachers as reflective learners. In: Hansen A, editor. Reflective Learning and Teaching in Primary Schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2012:32–48. doi:10.4135/9781526401977.n3

53. Souba WW, Day DV. Leadership values in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2006;81(1):20–26. doi:10.1097/00001888-200601000-00007

54. Reinertsen JL. Physicians as leaders in the improvement of health care systems. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(10):833–838. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-128-10-199805150-00007

55. McAlearney AS. Using leadership development programs to improve quality and efficiency in healthcare. J Healthc Manag. 2008;53(5):319–331. doi:10.1097/00115514-200809000-00008

56. Lee TH. Turning doctors into leaders. Harv Bus Rev. 2010;88(4):50–58.

57. Jakobsen RB, Gran SF, Grimsmo B, et al. Examining participant perceptions of an interprofessional simulation-based trauma team training for medical and nursing students. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(1):80–88. doi:10.1080/13561820.2017.1376625

58. McAlearney AS. Leadership development in healthcare: a qualitative study. J Organ Behav. 2006;27(7):967–982. doi:10.1002/job.417

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.