Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 10

Household flood preparedness and associated factors in the flood-prone community of Dembia district, Amhara National Regional State, northwest Ethiopia

Authors Ashenefe B, Wubshet M, Shimeka A

Received 12 November 2016

Accepted for publication 23 March 2017

Published 31 May 2017 Volume 2017:10 Pages 95—106

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S127511

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Carole Baskin

Baye Ashenefe,1 Mamo Wubshet,2 Alemayehu Shimeka3

1North Gondar Zonal Health Department, 2Department of Public Health, St Paul Millineum Medical College, Addis Ababa, 3Department of Epidemiology and Bio-Statistics, Institute of Public Health, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

Background: Flood preparedness empowers the community to respond effectively to related hazards. However, there was no research done in the country concerning household flood preparedness. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess household flood preparedness and associated factors in the flood-prone community of Dembia district, northwest Ethiopia.

Methods: A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from March to April 2014 in the Dembia district. A two-stage sampling technique was used. The study was conducted using 806 flood-prone participants. An interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. The collected data were entered using Epi info version 3.5.1 and transported into SPSS version 16 for further analysis. Descriptive and analytic statistics were computed. Variables having association with the outcome variable were reported using odds ratio with 95% confidence interval (CI). Model fitness was checked by Hosmer and Lemeshew chi-square test.

Results: Household flood preparedness was found to be 24.4%. The age group of ≥ 46 years (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=2.62; 95% CI: 1.12, 6.00) above, monthly household income >893 Ethiopian Birr, (AOR=6.72; 95% CI: 2.2 7, 19.88) attending primary level education (AOR=22.08; 95% CI: 8.16, 59.74), warning system in household (AOR=5.41; 95% CI: 2.38, 12.32), knowledge of flood prevention, (AOR=2.52; 95% CI: 1.43, 5.57) were positively associated with household flood preparedness.

Conclusion and recommendation: This study has demonstrated that household flood preparedness was found to be low in the study area. Household flood preparedness was significantly associated with the older age group, attending primary level education, having a higher monthly income, receive household level warning messages, having knowledge on preparedness, prior exposure to a flood, and length of flood >6 days. Strengthening household flood preparedness in advance is important in order to prevent flood and its related consequences.

Keywords: household, flood preparedness, flood, Ethiopia

Introduction

Ethiopia is one of the flood-prone countries in Africa. The worst flood incidence occurred in the summer of 2006 as a result of prolonged and intensive rainfall, which resulted in flash floods and overflow of rivers and dams affecting 199,900 people in eight regions of the country. This resulted in loss of lives, damage of properties, and destruction of livelihoods of tens of thousands of people. All measures and policies taken before an event for the prevention, mitigation, and readiness constitute household preflood preparedness. Preparedness is a continuous cycle. The measures taken by the households to strengthen this preparedness cycle were planning, organizing, training, equipping, exercising, evaluation and improvement activities to ensure effective coordination, and enhancing capabilities to prevent, protect against, respond to, recover from, and mitigate the effects of flood disasters. Preparedness includes designing warning systems, planning for evacuation and reallocation, storing food and water, building temporary shelters, devising management strategies, and holding disaster drills. Contingency planning is also included in the preparedness and planning for post-risk response and recovery. A recent policy regarding the households preparedness has suggested that improving preparedness of the communities is the key to the success to reduce flooding disaster risk, and this is closely linked to economic status and knowledge because top–down programs in which communities are not involved tend to reach those worst affected by disaster, and may even make them more vulnerable.1,2

The most important challenge is to change from concentrating solely on postdisaster relief and focus on predisaster preparedness because of various factors, such as strengthening awareness of the community and supplying resources. Evidences showed that for every dollar spent on prevention and preparedness, ~100 dollars or more is needed for relief efforts after the disaster has taken place. Flood preparedness empowers households and communities to respond effectively to hazards associated with flood.1,3,4 However, there was no research done in the country concerning household flood preparedness. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess flood preparedness of the households and associated factors in a flood-prone community in Dembia district, northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design

Community-based cross-sectional study was conducted to assess flood preparedness of the households and associated factors in a flood-prone community of Dembia district.

Study setting

Ethiopia is one of the countries that follow federal system of administration, and within this federal country, there are nine ethnic states. Thus, Amhara is one of the states mainly inhabited by the people of Amhara. These people are found in the northern and central parts of the country, mainly in the highland segment of the country. Each region has zones, lower units of administration. This particular study was conducted in Dembia district, North Gondar zone, one of the zones of Amhara region, from March to June 2014. The district is bordered by the largest lake of the country, Lake Tana. Dembia district is located in northwest of Ethiopia, 775 km from the capital city Addis Ababa. The district lies in an elevation between 1400 and 2700 m above sea level. Administratively the district is divided into 45 kebeles, which are the lowest governmental administrative units of the government of Ethiopia, of which 5 kebeles are urban and 40 kebeles are rural. Twelve kebeles of the district were flood prone. The flood-prone community is uniformly resided and found at the periphery of Lake Tana. The estimated number of household heads in the flood-prone community is about 26,465, which consisted of an estimated 70,930 adult populations aged ≥18 years (Figure 1).5

| Figure 1 Map of study area. |

Source and study population

The source populations were household heads aged ≥18 years living in the flood-prone community of the district. In this study, fathers or, in some households, mothers were the leaders or managers of their households, and thus, they were considered as heads of households and selected to be the study subjects, considering them as more experienced, responsible, and involved in the households flood preparedness than the other members of the households. The study populations were those household heads with similar age group living in the six selected flood-prone kebeles of the district.

Inclusion and exclusion

All selected household heads who lived at least for 1 year in the study area were included in the study. Heads of households who were unable to give the required information because of different reasons such as unable to hear were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination

Sample size was calculated using single population proportion formula, n=z2a/2(p×[1−p])/d2, and assuming the proportion of household’s flood preparedness as 50% because there is no similar study done so far, the precision as 5%, and 95% confidence level. Finally, the sample size was found to be 384. Considering the design effect of two and possible nonresponse rate of 5%, the minimum sample size required was calculated to be 806.

Sampling procedure

A two-stage sampling technique was used. Initially, from the 12 rural flood-prone kebeles, six were selected randomly using lottery method. Then, individual households in the selected kebeles were drawn using a simple random sampling technique. List of households in the selected kebeles were obtained from each kebele office. The number of households that were included among the selected kebeles was determined to be proportional to the household size. When eligible participants were not available at home during data collection, the interviewers had revisited twice again, and finally if unable to get the household head, the next immediate household was taken.

Variables

The dependent variable of this study was household flood preparedness, whereas independent variables included age, educational level, household monthly income, employment status, housing condition, awareness, and knowledge of flood preparedness.

Operational definitions

Household flood preparedness

In this study, households who were found to have included 11 items in the flood preparedness emergency kit during the data collection period were considered as prepared households. Those 11 items in the emergency kit during the data collection period were emergency warmth and shelter, food, tools, water, receiving training, batteries, developed a reconnection plan for evacuation where to go and whom to call, personal sanitation, battery-powered radio and/or cell phone, first-aid kit, and necessary documents.

Awareness

Household heads were considered as having awareness if they responded “Yes” for the question “Have you ever received any information about the awareness of household flood preparedness through warning, training and experience?”

Warning system in the households

When participants currently used at least one warning system in the households such as cell phone, microphone, and warning using local materials.

Knowledge

When respondents responded “Yes” for the question “Do you know about household’s preparation for flooding?”

Flood experience

When subjects were exposed to flood disaster at least once in their life time.

Prior exposure

When subjects were exposed to flood disaster in the last rainy season.

Data collection tools

To assess household flood preparedness and associated factors, structured and interviewer-administered questionnaire was used. The questionnaire was pretested in other flood-prone areas that were not included in the main study (Figure S1).

Data collection procedure

Data were collected using a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire having two main parts. The first part contained information on sociodemographic characteristics, whereas the second part contained information on awareness, knowledge, and household flood preparedness. The questionnaire6 was translated into Amharic and back-translated to English for its consistency. A total of six diploma-level data collectors and two BSc-holding supervisors were employed after training on the main aim of the study, the techniques of data collection, and the confidentiality of the data. Respondents were asked whether they know and made any flood preparation by themselves in order to make their households and homes safer from flood disaster. If the respondents had replied that they were aware and prepared for flood, the data collector selected items from their emergency kit checking the 11th item in the kit.

Data quality control

The quality of data was assured by giving emphasis in designing data collection tools, and pretesting and training the data collectors and supervisors. Daily supervision was conducted and corrections were made accordingly.

Data processing and analysis

Data were checked, coded, and entered to Epi info version 3.5.1 and exported to SPSS statistical software version 16 for analysis. Both descriptive and analytic statistics were computed. The fitness of the model was checked using Hosmer and Lemeshew chi-square test. Bivariable analysis was used to screen eligibility of the independent variables. All variables with a p-value of <0.2 in the bivariable analysis were entered into the multiple logistic regression model to identify the net effect of factors associated with household flood preparedness. Multicollinearity within independent variables was checked using variance inflation factor.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of the University of Gondar. A permission letter was obtained from Dembia district administrative office and communicated to each selected kebele. Study participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the importance of their participation, and the right to withdraw from the study at any time they want. Verbal consent was obtained prior to data collection. Confidentiality of information was kept through securing the data in a locked room and using passwords in computers. Consent to publish is secured from study participants.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

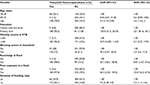

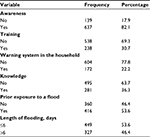

Among 806 eligible participants, 776 were interviewed, making the response rate 96.3%. The majority of respondents were men, 663 (85.45%). Respondents’ age ranged from 21 to 90 years with a mean age of 45 years. Six hundred forty-one (82.6%) of the participants were married. More than two-third (66.2%) of the participants were unable to write and read (Table 1, Figure S2).

| Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants in the Dembia district, northwest Ethiopia, 2014 Abbreviation: ETB, Ethiopian birr. |

Awareness and knowledge of the respondents toward flood preparedness

Of the total participants, 82.1% had awareness on flood prevention and preparedness during this study, 238 (30.7%) had taken training, and 176 (22.2) had warning system in their household. Mobile was a means of information sharing for household warning system for 176 (22.2) respondents. Two hundred eighty-one (36.1%) respondents reported that they had knowledge on household flood preparedness and 100% of the respondents had flood experiences (Table 2).

| Table 2 Knowledge and awareness of participants on household flood preparedness in the flood-prone community, Dembia district, northwest Ethiopia, 2014 |

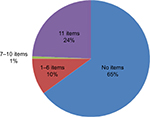

Household flood preparedness in Dembia district

Respondents were asked 11-item questions to assess household flood prevention and preparedness. Accordingly, respondents were classified as having no score or items, have some items, and have all the 11 items in their flood preparedness emergency kit according to their demographic characteristics, economic status, and knowledge, based on their capacities. It was triangulated with observation of the items in the emergency kit. Thus, 189 (24.4%) of the respondents had household flood preparedness, whereas the remaining 587 (75.6%) respondents did not have preparedness (Figure 2).

| Figure 2 Distribution of scores for cutoff point selection of the 11-item questions among heads of household respondents in the flood-prone Dembia district, northwest Ethiopia. |

Factors associated with household flood preparedness

Variables such as gender, age, educational status, religion, household income, occupation, marital status, family size, house ownership, warning system in household, knowledge, prior exposure, previous flood experience, awareness, any training for flood prevention and preparedness, and duration of flooding were found to be eligible for multivariable logistic regression. In the multivariable analysis, age, household monthly income, educational status, warning system in household, knowledge, prior exposure, and duration of flooding were significantly associated with household flood prevention and preparedness.

Individuals who were aged ≥46 years were nearly three times more likely to have household preparedness compared with those aged 18–28 years (AOR=2.62; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.12, 6.00). The odds of having preparedness among individuals who had primary level of education were found to be higher compared with individuals who were unable to read and write (AOR=22.08; 95% CI: 8.165, 59.74). Income was also found to be statistically significant with household flood preparedness. Households having monthly income >893 Ethiopian birr were nearly 6.7 times prepared compared with those who had ≤893 birr (AOR=6.72; 95% CI: 2.27, 19.88). The odds of being prepared for flood among those having warning system in the household were higher than those who did not have (AOR=5.41; 95% CI: 2.38, 12.32). Respondents having knowledge on household preparedness were more likely to be prepared compared with less knowledgeable individuals (AOR=8.91; 95% CI: 1.67, 47.57). The odds of being prepared among those who had prior exposure were higher compared to those with no such exposure (AOR=32.67; 95% CI: 6.15–67.46). The odds of household preparedness were three times higher among those experiencing >6 days of flood compared with those experiencing ≤6 days duration of flood (AOR=2.52; 95% CI: 1.43, 5.57; Table 3).

Discussion

This study has tried to assess household flood preparedness and the associated factors among the flood-prone communities of Dembia district. The findings indicated that household flood preparedness was lesser (24.4%). Factors such as age, household monthly income, educational status, warning information in household, knowledge of flood, prior exposure of flood, and duration of flooding were significantly associated with household flood prevention and preparedness.

Age was positively correlated with household flood preparedness. Households led by older individuals were 2.62 times more likely to have household preparedness compared with those aged households headed by younger ones (AOR=2.62; 95% CI: 1.12, 6.00). Previous studies suggested that older household heads were more likely prepared based on their flood experience.7 This might be due to the fact that older respondents had more basic supplies to survive before and after a disaster as a result of previous knowledge about vulnerable area.

This study also showed that household heads with primary level of education were highly prepared compared with those unable to read and write. Previous studies indicated that primary level of education was positively correlated with household flood.8 The possible explanation of this relationship could be explained by knowledge, skills, and access to more information in order to decrease vulnerability and insecurity that contributes to household preparedness to flood.

Households with better monthly income were found to be better prepared than those with lower monthly income. This was supported by another study that showed that households with lower income had low level of preparedness than those with higher income.9 This might be due to the fact that those with better income may have adequate resources, which could enhance their preparedness efforts.

Household warning system was positively correlated with flood preparedness. In this study, mainly battery-powered radio and/or cell phone were used as warning systems. Thus, respondents having either battery-powered radio or cell phone as a warning system in the household were more likely prepared than those who had neither of them. Previous studies suggested that a targeted flood warning service in the household raised their awareness regarding preparedness activities. Those who believe that household protection is a personal responsibility have showed higher levels of preparedness than those who did not believe.3

Knowledge was positively correlated with household flood preparedness. Respondents having knowledge of household flood preparedness were more likely to be prepared than those who did not have knowledge. This could be explained by that those who had knowledge on what should be included in an emergency kit were more likely prepared than those who lack the knowledge. This finding was supported by previous studies, which indicated that lack of knowledge was a barrier to accomplishing preparedness activities.10

There was a strong association between prior exposure and household flood preparedness. This finding was found consistent with another study, which showed that prior exposure to major flooding events increases individual preparedness among high-flood risk populations.11 This could be due to recalling of the prior serious physical and economical damage as well as fear similar flooding events in the future.

Duration of flooding was positively associated with household flood preparedness. Households experiencing >6 days length of flooding were better prepared than those experienced ≤6 days of flooding. The possible reason could be increased length of flooding, causing serious damage, which could enhance individual’s knowledge of future hazards and preventive measures.

Gender was not significantly associated with household flood preparedness. This finding was not in line with previous studies that indicated that gender was related to household flood preparedness.12 The reason for this difference could be that gender alone might not be a sufficient predictor of household preparedness, rather household flood preparedness related to obtaining knowledge, skills, and resource.13

Home ownership was not associated with household flood preparedness. This was also not consistent with previous studies that indicated that home ownership was significantly associated with household flood preparedness.14 The possible explanation for this finding could be that household’s flood preparedness was not due to having home or not but a result of the presence of property, better knowledge of options for action, and financial resources.

Previous flood experience was not associated with household’s flood preparedness. This finding was not in line with the findings of other studies that indicated that prior flood disaster experience has a significant association with household flood preparedness for future flood disaster.7,15 This could be due to the fact that as time laps, the impact of disaster experience on future preparedness behaviors may fade up.

Conclusion

Household flood preparedness in the flood-prone community of Dembia district was found to be low. Age of household heads, education, monthly income, household warning system, knowledge on flood preparedness, prior exposure of flood, and duration of flooding were significantly associated with household flood preparedness.

Recommendation

In light of the findings of the study, the authors recommended that, in addition to community flood preparedness strategies, concerned bodies should strengthen household flood preparedness considering the knowledge of the community, age of household heads, income level, and duration of flood they have experienced.

Acknowledgments

Our special thanks and sincere appreciation go to the University of Gondar for the financial support of this study. We are highly indebted to Dembia district, all study participants, data collectors, and supervisors. University of Gondar funded this study.

Author contributions

BA designed the study, involved in proposal development, supervised data collection, and participated in data analysis and interpretation of the data. MW and AS assisted in the design of the study, proposal writing, data analysis, and interpretation of the study. All authors were responsible for data collection, initial analysis, and drafting of manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

S. Lelisa W/M.K. Lecture note For Health Science Students, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education, Jimma University; 2006. | ||

Shaw R, Goda K. From disaster to sustainable civil society: the Kobe experience. Disaster. 2004;28(1):16–40. | ||

Mercy Corps. Establishing Community Based Early Warning System: Practitioner’s Handbook. Mercy Corps and Practical Action, 2010. | ||

R. S. Community based disaster management: challenges of sustainability. In proceedings, Third Disaster Management Practitioners’ workshop for Southeast Asia, Bangkok, Thailand, 2004; 113–117. | ||

Dembia district information communication office annual report 2012. | ||

World Health organization. Health Aspects of Emergency Preparedness and Response; 2005 Report of the Regional Meeting; Regional Office for South-East Asia New Delhi; November 21–23, 2005; Bangkok. | ||

Kirschenbaum A. Disaster preparedness: a conceptual and empirical reevaluation. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters. 2004;20(1). | ||

Menard L, Slater RO, Flatz J. Disaster preparedness and educational attainment. J Emerg Manag. 2011;9(4):45–52. | ||

Phillips BD, Metz WC, Nieves LA. Disaster threat: preparedness and potential response of the lowest income quartile. Environmental Hazards. 2005;6:123–133. | ||

Tierney KJ, Lindell MK, Perry RW. Facing the Unexpected: Disaster Preparedness and Response in the United States. Washington DC: John Henry Press; 2001. | ||

Takao K, Motoyoshi T, Sato T, Fukuzono T, Seo K, Ikeda S. Factors determining residents’ preparedness for floods in modern megalopolises: the case of the Tokai flood disaster in Japan. J Risk Res. 2006;7(7–8):775–787. | ||

Siegel JM, Shoaf KI, Afifi A, Bourque LB. Surviving two disasters: does reaction to the first predict response to the second? Environment Behavior. 2003;35(5). | ||

Kirschenbaum A. Disaster preparedness: a conceptual and empirical reevaluation. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters. 2002;20(1):5–28. | ||

Kirschenbaum A. Families and disaster behavior: a reassessment of family preparedness. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters. 2006;24(1):111–143. | ||

Harvatt J, Petts, J,Chilvers, J. Understanding householder responses to natural hazards: flooding and sea-level rise comparisons. J Risk Res. 2011;14(1):63–83. |

Supplementary materials

| Figure S1 Information sheet and consent form. |

| Figure S2 English Version Questionnaire. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.