Back to Journals » Patient Related Outcome Measures » Volume 10

Hemophilia and sexual health: results from the HERO and B-HERO-S studies

Authors Blamey G, Buranahirun C, Buzzi A, Cooper DL , Cutter S, Geraghty S , Saad H, Yang R

Received 6 April 2019

Accepted for publication 9 July 2019

Published 14 August 2019 Volume 2019:10 Pages 243—255

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PROM.S211339

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Robert Howland

Greig Blamey,1 Cathy Buranahirun,2 Andrea Buzzi,3 David L Cooper,4 Susan Cutter,5 Sue Geraghty,6 Hossam Saad,4 Renchi Yang7

1Physiotherapy Department, Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada; 2Children’s Center for Cancer and Blood Diseases, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California/Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA; 3Fondazione Paracelso, Milan, Italy; 4Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, NJ, USA; 5Penn Comprehensive Hemophilia and Thrombosis Program, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 6University of Colorado Hemophilia and Thrombosis Center-Retired, Denver, CO, USA; 7Tianjin Hemophilia Center, Tianjin, People’s Republic of China

Background: Sexual health plays a primary role in quality of life (QoL) for many people, including those with hemophilia; however, there is little information available about sexual relationships and satisfaction in patients with hemophilia.

Methods: To address this issue, the Hemophilia Experiences, Results and Opportunities (HERO) and the Bridging Hemophilia B Experiences, Results and Opportunities into Solutions (B-HERO-S) studies included questions from the Male Sexual Health Questionnaire (MSHQ).

Results: Although these data were not statistically analyzed for comparisons between the 3 populations (HERO, HERO US only, and B-HERO-S), in general, participants in the HERO survey appeared to be more satisfied with their sexual relationship than participants in the B-HERO-S survey. In addition, many patients, especially those outside the United States, reported that they had not discussed sexual health with their doctor or other members of the hemophilia treatment center team. While the topic of sexual health has been infrequently explored in men with hemophilia, this is the first time it has been investigated in women with hemophilia.

Conclusion: The results of these studies demonstrate that the impact of hemophilia extends to intimacy and suggest the need for large-scale studies in additional countries to explore further the factors associated with sexual health issues in people with hemophilia.

Keywords: Male Sexual Health Questionnaire, quality of life, sexual relationships

Introduction

Hemophilia is a congenital disorder caused by a deficiency in the blood coagulation factors VIII (hemophilia A) or IX (hemophilia B).1 People with hemophilia may bleed into joints, which can lead to swelling and pain.1 Treatment includes physical therapy, surgery, psychosocial care, and factor replacement therapy, which can be administered on-demand to stop bleeding after trauma and/or at regular intervals to prevent bleeding episodes (prophylaxis). Hemophilia clearly affects patients physically, but social and psychological issues surrounding this disorder, including sexual health, are less obvious.

The Hemophilia Experiences, Results and Opportunities (HERO) study was designed to better understand the psychosocial issues of patients with hemophilia and their caregivers.2 Conducted in 10 countries, this study evaluated male patients, most of whom had moderate to severe hemophilia A, using surveys regarding quality of life (QoL), relationships, and treatment, in an effort to identify their challenges and unmet needs.2 The Bridging Hemophilia B Experiences, Results and Opportunities into Solutions (B-HERO-S) study, which was conducted in the United States, included adult male and female patients with hemophilia B. It evaluated the impact of hemophilia B on education, employment, relationships, and physical activity.3 Notably, both the HERO and B-HERO-S studies included questions from the Male Sexual Health Questionnaire (MSHQ), a survey developed to assess sexual function and satisfaction in men with urogenital health concerns.4

A large study of adults in the United States, including those with chronic health conditions, indicated that sexual health and sexual satisfaction are highly important to QoL.5 Although sexual health also plays a primary role in QoL for people with hemophilia, information about sexual relationships and satisfaction in this patient population is lacking. The quality of their sexual relationships may be hindered by several issues. Joint disease may negatively affect comfortable sexual positioning, and chronic pain may inhibit sexual desire and/or physical ability to participate in sexual intercourse. Patients and/or their partners may not be receptive to alternative sexual pleasuring not involving penetration. History of iliopsoas bleeds and other bleeding events caused by sexual activity may also hinder their sexual relationships. Some females with hemophilia and their partners may be reluctant to engage in sexual activity during heavy and/or prolonged menstrual bleeding. Self-esteem can also negatively affect an individual’s sexual QoL; people with hemophilia may be at increased risk for negative body image because of their physical limitations. The aim of this analysis was to evaluate sexual health in patients with hemophilia through the MSHQ and to identify unmet needs in this patient population.

Materials and methods

Detailed methodologies of the HERO and B-HERO-S studies have been described elsewhere2,3 and will be briefly summarized here.

The HERO study was a global survey with participants in 10 countries: Algeria, Argentina, Canada, China, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The survey was approved by institutional review boards (IRBs) in Canada and the United States and by IECs in the other 8 countries. The committees waived informed consent due to limited risk; limited consent elements were provided in the assent that participants viewed. The survey, which was composed of 100+ multiple-choice and rating scale questions, was completed between June 2011 and February 2012 by adult (aged ≥18 years) male patients with hemophilia A or B with or without inhibitors who were recruited through national hemophilia organizations. Inclusion criteria were consistent across countries; participants must have had at least one spontaneous bleed into one or more joints within the previous 12 months or received regular replacement therapy for hemophilia.2

The B-HERO-S study employed an online questionnaire of approximately 100 multiple-choice and rating scale items. This survey was approved by an IRB (Quorum Review IRB, Seattle, WA, USA); informed consent was waived for the study due to minimal risk criteria based upon IRB review and approval. Participants were from the United States only and were recruited using an approved letter sent via social media and email from patient advocacy groups. Surveys were completed between September 24 and November 3, 2015, by adult (aged ≥18 years) male and female patients with hemophilia B. Exclusion criteria included an inability to understand and comply with English instructions and previous completion of the B-HERO-S survey with compensation. Information collected included demographics, medical history, and health-related QoL.3

All respondents to both the HERO and B-HERO-S surveys who reported being “married” or “in a relationship” were given the option to answer additional questions concerning their sexual health and intimacy as part of a subscale of the MSHQ. Additional questions concerning the impact of hemophilia on their sexual health were also included. All MSHQ questions were gender neutral, and male-specific response options were removed from the B-HERO-S survey.

Analysis

No statistical comparisons between the groups were performed because they were convenience samples, and statistical tests would have been underpowered. Data are presented as percentages of respondents of the HERO survey from all countries (HERO all respondents), HERO respondents from the United States only (HERO US only), and respondents of the B-HERO-S survey (B-HERO-S).

Results

A total of 675 adult males with hemophilia A or B (median age, 36 years; range, 18–86 years) participated in the HERO study, and 299 adults with hemophilia B (213 males and 86 females; median age, 29 years; range, 18–70 years) participated in B-HERO-S (Table 1). Most B-HERO-S respondents had moderate hemophilia B (63%), 25% had mild hemophilia B, 11% had severe hemophilia B, and 1% had inhibitors. Hemophilia severity data were not collected during the HERO study, however, the inclusion criteria for the survey were characteristic of moderate-severe hemophilia.

|

Table 1 Demographics and rate of response to the subscale of the MSHQ among participants in the HERO and B-HERO-S studies |

Eighty-five percent of HERO participants, 81% of HERO US only participants, and 43% of B-HERO-S participants who qualified to respond to the MSHQ questions chose to do so (Table 1). HERO respondents reported being married/in a relationship for a median (Q1, Q3) of 132 (60, 240) months (Table 2). HERO respondents from the United States reported they had been married/in a relationship for a median (Q1, Q3) of 120 (72, 204) months, and B-HERO-S respondents reported that they had been married/in a relationship for a median (Q1, Q3) of 4 (2.25, 5.75) years, which is equivalent to a median of 48 (27, 69) months.

|

Table 2 Response breakdown to “How long have you been married/in a relationship with your partner?” |

The initial set of questions from the subscale of the MSHQ focused on respondents’ satisfaction with elements of their relationship with their main partner over the past month. Forty-one percent of all HERO, 30% of HERO US only, and 17% of B-HERO-S respondents (18% males, 15% females; Table S1) reported being “extremely satisfied,” and 37% of all HERO, 38% of HERO US only, and 37% of B-HERO-S respondents (40% males, 30% females; Table S1) reported being “moderately satisfied” with their overall sexual relationship (Figure 1). Thirty-nine percent of all HERO, 29% of HERO US only, and 15% of B-HERO-S respondents (14% males, 20% females; Table S1) were “extremely satisfied” with the quality of their sex life. When asked about satisfaction with the number of times they have had sex over the past month, 27% of all HERO, 21% of HERO US only, and 11% of B-HERO-S respondents (14% males, 5% females; Table S1) were “extremely satisfied.” Forty-three percent of all HERO, 33% of HERO US only, and 16% of B-HERO-S respondents were “extremely satisfied” with the way they/their partner show affection during sex, and 43% of all HERO, 30% of HERO US only, and 13% of B-HERO-S respondents were “extremely satisfied” with the way they communicate about sex. When asked about satisfaction with all other aspects of their relationship aside from sex, 57% of all HERO, 44% of HERO US only, and 21% of B-HERO-S respondents (24% males, 15% females; Table S1) were “extremely satisfied.”

|

Figure 1 Impact of hemophilia on intimacy. Respondents rated their satisfaction with elements of their relationship with their main partner. |

Fifty-three percent of all HERO respondents reported that hemophilia has affected the quality of their sex life, and 68% of HERO US only respondents and 74% of B-HERO-S respondents (74% males, 75% females; Table S1) agreed (Figure 2). When given options to describe how hemophilia has affected the quality of their sex life, the most frequently selected answer by HERO respondents (all and US only) was “limitations in my movements” (all, 60%; US only, 43%; Figure 3). However, the most frequently selected answer by B-HERO-S respondents was “have previously bled as a result of having sex” (40%; 41% males, 40% females; Table S1). Fifty-three percent of all HERO respondents selected “affected by HIV/HCV,” compared with 27% of HERO US only and 8% of B-HERO-S respondents. Notably, the HERO study included participants from both developed and emerging countries. People with hemophilia in emerging countries are less likely to have access to effective HIV treatment and hepatitis C virus (HCV) eradication therapies, and thus, are more likely to have symptomatology from their viral infections that can hinder their sexual QoL. In addition, 32% of HERO, 32% of HERO US only, and 29% of B-HERO-S respondents reported that the “impact of hemophilia in other areas has also affected my sex life.” Sex differences were evident in a few of the responses. For example, 47% of B-HERO-S females, compared with 11% of B-HERO-S males, reported a “fear of causing a bleed as a result of having sex” (Table S1). In addition, 27% of male but no female B-HERO-S respondents reported “side effects of medications” as a reason that hemophilia affects their sex life (Table S1).

|

Figure 2 Belief about whether hemophilia has had an impact on respondents’ sex lives. |

|

Figure 3 Ways in which hemophilia has had an impact on respondents’ sex lives. |

Twenty-six percent of B-HERO-S respondents (28% males, 20% females; Table S1) reported having sexual intercourse 7 to 10 times in the past month (Figure 4). Only 11% of all HERO and 13% of HERO US only respondents reported having intercourse 7 to 10 times in the past month.

|

Figure 4 Number of times respondents had sexual intercourse during the previous month. |

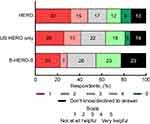

Fifty-six percent of B-HERO-S respondents (58% males, 50% females; Table S1) reported that they had discussed their sex life with their hemophilia doctor or a member of his/her team; however, only 28% of all HERO respondents reported having such a conversation (Figure 5). This response also varied widely across countries (Table 3). When asked to rate this discussion on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all helpful) to 5 (very helpful), 67% of all HERO respondents selected “helpful” or “very helpful” (Figure 6). Similar numbers of HERO US only and B-HERO-S respondents selected “helpful” or “very helpful” (HERO US only, 73%; B-HERO-S, 82%; 83% males, 80% females; Table S1). Among respondents who had not discussed their sex life with their hemophilia doctor or a member of his/her team, none from the B-HERO-S study said that such a conversation would be “very helpful;” however, 9% of all HERO and 5% of HERO US only respondents believed that it would be “very helpful” (Figure 7). Thirty-two percent of all HERO, 26% of HERO US only, and 23% of B-HERO-S respondents (19% males, 30% females; Table S1) expressed the belief that it would be “not helpful at all” to discuss their sex life with their hemophilia doctor. For the HERO study, responses varied by country, but most respondents did not believe that speaking with their doctor or a member of his/her team would be helpful (Figure 8).

|

Table 3 Response breakdown to “Have you discussed your sex life with your hemophilia doctor or his/her team?” |

|

Figure 5 Percentage of respondents who have discussed their sex life with their hemophilia doctor or a member of his/her team. |

|

Figure 6 For respondents who discussed their sex life with their hemophilia doctor or a member of his/her team, belief that the discussion was helpful. |

|

Figure 7 For respondents who did not discuss their sex life with their hemophilia doctor or a member of his/her team, belief that such a discussion would be helpful. |

|

Figure 8 For HERO respondents who did not discuss their sex life with their hemophilia doctor or a member of his/her team, belief that such a discussion would be helpful. |

Discussion

The MSHQ results from the HERO and B-HERO-S surveys provide insight into the impact of hemophilia on sexual health in adults across 10 countries, including the United States. While this topic has been infrequently explored in men with hemophilia, this is the first time it has been explored in women with hemophilia. Although these data were not statistically analyzed for comparisons between the 3 populations (HERO, HERO US only, and B-HERO-S), in general, respondents with moderate to severe hemophilia from the HERO survey across 10 countries appear to be more satisfied with their sexual relationship than respondents with predominantly mild to moderate hemophilia from the US-only B-HERO-S survey. When asked about their satisfaction with elements of their relationship with their main partner in the past month, US respondents (HERO and B-HERO-S) appeared to be less satisfied than global HERO respondents. This may reflect cultural influences or differences in disease severity, joint status, or respondent age between US and global respondents. In addition, B-HERO-S respondents were on average younger than those in HERO. Participant age may affect a number of factors, including the duration of a relationship and overall joint health, and may, therefore, have influenced subsequent MSHQ responses.

When asked to identify how hemophilia affects their sex life, the most popular response for B-HERO-S participants was “having previously bled as a result of sex.” This response, coupled with a “lack of desire,” seems to be more prevalent and impactful in US respondents and even more prevalent in the mild to moderate hemophilia US population represented in B-HERO-S. The prevalence of these responses could be due to target joints, a lack of adherence to treatment regimens, or sexual positions as some may be more likely than others to cause bleeds. The musculoskeletal demands and the matching of those demands to the individual joint health and bleeding history of each patient have an impact on whether a particular sexual position might be likely to cause a bleed. Generally, participants’ responses may reflect a need for greater education regarding the potential musculoskeletal impact of sexual activity and better hemostatic coverage during sexual activity, particularly for patients with mild to moderate disease. Moreover, these responses may highlight a need for physical therapy, to maximize musculoskeletal health and enable better resilience and protection against bleeding. A greater percentage of global HERO respondents compared with HERO US only and B-HERO-S respondents reported that HIV/HCV influences their sex life. This may be related to the previously mentioned lack of access to HIV/HCV treatments and/or issues related to disclosure in emerging countries. Responses also differed between males and females, suggesting that hemophilia presents different barriers to sexual activity for each sex. For example, in women, heavy, frequent, and/or prolonged menses may cause abdominal pain and/or may be perceived as embarrassing during sexual activity. It is, however, unclear how additional confounding factors may have been differently represented between men and women.

Most B-HERO-S respondents, both male and female, have discussed their sex life with their hemophilia doctor or a member of his/her team. Most respondents who had this discussion found it to be helpful. Male and female respondents agreed that the conversation was helpful, although males were somewhat more likely than females to view it as helpful. HERO US only respondents were more likely than global HERO respondents to discuss their sex life with their hemophilia doctor. It is possible that in developing countries, the focus of discussions is more on general health and less on sexual health. Cultural influences may play a role in the decision about whether to have this discussion with a doctor; sex may not be discussed in many cultures, especially with a physician. Importantly, respondents from both surveys who had not spoken to their hemophilia doctor about their sex life believed that such a conversation would not be helpful at all. Patients may perceive that their physician does not understand the impact of hemophilia on their sex life and/or they may not consider sexual health to be in the realm of their hemophilia care. In addition, global HERO responses on the potential helpfulness of this discussion varied by country, which may reflect differences in patient backgrounds and previous sexual experiences that influence awareness, willingness, openness, and outcomes of interactions with health care providers (HCPs) around sexual health. These differences could also reflect the overall variability in the management of hemophilia across countries. Many hemophilia treatment center (HTC) team members do not ask about sexual health due to time constraints, their own discomfort with the topic, or their perceptions/assumptions surrounding sex, thereby denying the opportunity for a patient or their partner to discuss their concerns. In addition, patients and HCPs may be more comfortable discussing sexual health with members of their same sex.

During the HIV/AIDS era, the primary focus on sexual health in hemophilia was on protection from sexually transmitted diseases, not sexual satisfaction; however, sexual health strongly influences QoL6,7 and is important to the overall management of people with hemophilia. Despite the implications for QoL, discussions of sexual health between patients with hemophilia and physicians do not appear to be standard.8,9 This problem has also been identified in other patient populations experiencing chronic illness, such as cancer,10 cystic fibrosis,11 lower back pain,12 type 2 diabetes,13 and rheumatoid arthritis.14 In these patients, sexual satisfaction is significantly correlated with QoL but is not routinely evaluated during QoL surveys or at routine doctor visits.15 Therefore, it has been widely suggested that sexual health be evaluated in patients with chronic illness on a regular basis.10,11,13–15

These studies did not assess to what extent patients discuss issues related to sexual health and well-being with other members of the hemophilia care team, including nurses, social workers, and physical therapists. This is worth further exploration. Evaluating and discussing sexual health should be normalized as part of routine care for patients with hemophilia. It is important for HCPs to offer a multipronged approach that includes communicating openly about sexual activity and QoL in a consistent, comprehensive manner. All members of the care team should be proficient in how to initiate and engage their patients in this conversation, because patients may be reluctant to initiate this conversation for a variety of reasons. It may be helpful to survey HTCs on their current practices in the management of patients’ sexual health (eg, determine whether they currently speak to patients about sexual health, explore how they engage in the conversation, ascertain whether they believe that it is their responsibility to discuss sexual health with patients, and identify the educational tools they use or need to facilitate this aspect of care). It is important for HTCs to view sex as a physical activity and an integral component of QoL. HTCs should reinforce a proactive approach to patient education in order to prevent bleeding (rather than wait for the patient to experience bleeding) and advise patients how best to engage in sex while recovering from a bleed.

One approach to introducing this topic during routine HTC visits could be to include standardized, self-rating patient preference tools, such as the MSHQ or the International Index of Erectile Dysfunction, in the battery of tests already administered. Members of the HTC team may benefit from using the outcomes of the tools as a conversation-starter. This method has also been suggested in previous studies of sexual satisfaction in patients with chronic illness.13 In addition, teaching tools have been developed to help HCPs address sexual health in patients with chronic illnesses.15–17 Specifically, the Canadian HERO National Advisory Board developed a pilot training program led by an expert from the Calgary Sexual Health Center to increase HCPs’ knowledge, skills, and comfort level surrounding sexual satisfaction in patients with hemophilia.16 Bitzer et al (2007) developed a tool to assist HCPs in evaluating sexual problems. This model takes three elements, descriptive sexological diagnosis, biopsychosocial model, and disease-specific factors, into consideration.17 Another group introduced the PLISSIT model of sexual counseling, which guides HCPs into a discussion and possible intervention of sexual health for patients dealing with chronic illness. This model walks HCPs through four levels, including permission, limited information, specific suggestions, and intensive therapy. The HCP is responsible for choosing the level of interaction with which they are most comfortable.15 The recently published Activity-Intensity-Risk Consensus Survey engaged HTC-based physical therapists to identify the range and drivers of risk of bleeding in 102 athletic activities. The results of the survey informed discussion guides that can be used by HTC team members to help patients with hemophilia identify activities that are safe and will enable them to maintain an active lifestyle.18 The results of the current study suggest that a similar evaluation of intimate activities would greatly benefit the hemophilia community.

This study had a few limitations. For example, the small sample size limited generalizability to the greater hemophilia population. In addition, not matching reported issues and behaviors of people with hemophilia with issues of the general population made it difficult to assess the significance of these results. Disease severity and arthropathy information was not collected from HERO respondents, who were presumed to have moderate to severe hemophilia based on inclusion criteria. In addition, potential differences in responses between bleeders and non-bleeders were not addressed. Recruitment bias was also a possible limitation, given that participants in the B-HERO-S study, for example, were recruited through advocacy organizations via social media and email, which may have led to enrollment of patients with more severe disease who were more likely to seek support from and be involved in the hemophilia B community. When compared with data from the Community Counts HTC Populations Profile, the B-HERO-S study enrolled approximately 9% of eligible adults and children (449 respondents of 5099 patients with hemophilia B in the United States).19 In addition, the HERO study used a convenience sample, which was not designed to be entirely representative or comparative, and importantly, this study did not include females. Respondents consisted of only those who disclosed that they were “married” or “in a relationship;” it excluded those who did not consider themselves to be in either of those categories. Finally, although only a subscale of the MSHQ was employed here, the instrument was developed and validated for males,4 possibly affecting the ability of this instrument to accurately assess the sexual health of female respondents in this study.

Conclusion

The impact of hemophilia extends to intimacy, and spans the range of disease severity, gender, and country of residence. These results suggest the need for large-scale studies in additional countries to further explore the factors associated with sexual health issues in people with hemophilia.

Abbreviations

B-HERO-S, Bridging Hemophilia B Experiences, Results and Opportunities into Solutions; HCP, health care provider; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HERO, Hemophilia Experiences, Results and Opportunities; HTC, hemophilia treatment center; IRB, institutional review board; MSHQ, Male Sexual Health Questionnaire; QoL, quality of life.

Acknowledgments

Writing assistance was provided by Amy Ross, PhD, of ETHOS Health Communications in Yardley, Pennsylvania, and was supported financially by Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, New Jersey, in compliance with international Good Publication Practice guidelines.

Disclosure

CB has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk Inc., although all have been unrelated to the subject matter discussed in this manuscript. DLC and HS are employees of Novo Nordisk Inc. AB reports grants from Bayer, CSL Behring, Kedrion, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Shire and Sobi, outside the submitted work. SC reports honoraria from Pfizer and from Novo Nordisk Inc., outside the submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Srivastava A, Brewer AK, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, et al. Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia. 2013;19(1):e1–47.

2. Forsyth AL, Gregory M, Nugent D, et al. Haemophilia Experiences, Results and Opportunities (HERO) study: survey methodology and population demographics. Haemophilia. 2014;20(1):44–51. doi:10.1111/hae.12239

3. Buckner TW, Witkop M, Guelcher C, et al. Management of US men, women, and children with hemophilia and methods and demographics of the Bridging Hemophilia B Experiences, Results and Opportunities into Solutions (B-HERO-S) study. Eur J Haematol. 2017;98(Suppl 86):5–17. doi:10.1111/ejh.12854

4. Rosen RC, Catania J, Pollack L, Althof S, O’Leary M, Seftel AD. Male Sexual Health Questionnaire (MSHQ): scale development and psychometric validation. Urology. 2004;64(4):777–782. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2004.04.056

5. Flynn KE, Lin L, Weinfurt KP, Dalby AR. Sexual function and satisfaction among heterosexual and sexual minority U.S. adults: A cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0174981. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174981

6. Wilmoth MC. Sexuality: a critical component of quality of life in chronic disease. Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42(4):507–514. doi:10.1016/j.cnur.2007.08.008

7. Dorner TE, Stronegger WJ, Rebhandl E, Rieder A, Freidl W. The relationship between various psychosocial factors and physical symptoms reported during primary-care health examinations. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2010;122(3–4):103–109. doi:10.1007/s00508-010-1312-6

8. Butler RB, Cheadle A, Aschman DJ, et al. National needs assessment of patients treated at the United States federally-funded hemophilia treatment centers. Haemophilia. 2016;22(1):e11–e17. doi:10.1111/hae.12810

9. Arnold E, Lane S, Webert KE, et al. What should men living with haemophilia need to know? The perspectives of Canadian men with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2014;20(2):219–225. doi:10.1111/hae.12297

10. Gilbert E, Perz J, Ussher JM. Talking about sex with health professionals: the experience of people with cancer and their partners. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016;25(2):280–293. doi:10.1111/ecc.12352

11. Aguiar KCA, Marson FAL, Gomez CCS, et al. Physical performance, quality of life and sexual satisfaction evaluation in adults with cystic fibrosis: an unexplored correlation. Rev Port Pneumol. 2017;23(4):179–192.

12. Pieber K, Stein KV, Herceg M, Rieder A, Fialka-Moser V, Dorner TE. Determinants of satisfaction with individual health in male and female patients with chronic low back pain. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44(8):658–663. doi:10.2340/16501977-0915

13. Bijlsma-Rutte A, Braamse AMJ, van Oppen P, et al. Screening for sexual dissatisfaction among people with type 2 diabetes in primary care. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31(11):1614–1619. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.07.020

14. Dorner TE, Berner C, Haider S, et al. Sexual health in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and the association between physical fitness and sexual function: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38(6):1103–1114. doi:10.1007/s00296-018-4023-3

15. McInnes RA. Chronic illness and sexuality. Med J Aust. 2003;179(5):263–266.

16. Bitzer J, Platano G, Tschudin S, Alder J. Sexual counseling for women in the context of physical diseases: a teaching model for physicians. J Sex Med. 2007;4(1):29–37. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00395.x

17. Sagermann L, Blamey G, Lane S, et al. A Pilot Program to Improve Sexual Health Communication for Healthcare Professionals Treating People with Hemophilia (PWH). Glasgow, Scotland: World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH); 2018 May 20–24.

18. Hernandez G, Baumann K, Knight S, et al. Ranges and drivers of risk associated with sports and recreational activities in people with haemophilia: results of the Activity-Intensity-Risk Consensus Survey of US physical therapists. Haemophilia. 2018;24(Suppl 7):5–26. doi:10.1111/hae.13623

19. Kline P. Computing Test-reliability. A Handbook of Test Construction: Introduction to Psychometric Design. New York, NY: Methuen & Co.; 1986:118–132.

Supplementary material

|

Table S1 Response breakdown between male and female respondents of the B-HERO-S study |

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.