Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 12

Health care transformation in a resource-limited environment: exploring the determinants of a good climate for change

Authors van Boekholt TA, Duits AJ , Busari JO

Received 11 November 2018

Accepted for publication 24 January 2019

Published 28 February 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 173—182

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S194180

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Tessa A van Boekholt,1 Ashley J Duits,2–4 Jamiu O Busari5,6

1Department of Public Health, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Uganda Operation, Arua, Uganda; 2Department of Medical Education, St. Elisabeth Hospital, Willemstad, Curaçao; 3Institute for Medical Education, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands; 4Red Cross Blood Bank Foundation, Willemstad, Curaçao; 5Department of Educational Development and Research, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, University of Maastricht, Maastricht, The Netherlands; 6Department of Pediatrics, Zuyderland Medical Center, Heerlen, The Netherlands

Purpose: In a continued effort to improve the health care services, a project was set up to develop and implement a care pathway for the effective management of pressure ulcers in the St Elisabeth Hospital in Curaçao, the Dutch Caribbean. To ensure the effective implementation of our intervention, we decided to investigate what factors define the implementation climate of a health care institution within a resource-limited environment.

Methods: We used a participatory tool approach in this study, where a mixed team of health professionals worked on two parts of a health improvement project, namely: 1) workforce leadership development through a clinical leadership training program; and 2) health care quality improvement through the pressure ulcer care pathway development. In-depth interviews were held with ten participants to gain insight into their experiences of the implementation climate in the hospitals and inductive analysis was used to identify the (sub)themes.

Results: Identified themes that described the implementation climate included: 1) the attitude of staff toward policy changes; 2) vision of the organization; 3) collaboration; 4) transparency and communication; 5) personal development; and 6) resources. These factors were interrelated and associated with several potential consequences such as loss of motivation among staff, loss of creativity to solve issues, the emergence of the feeling “us” vs “them”, short-term solutions to problems, and a sense of suspicion/frustration among staff members.

Conclusion: From this study, positive subconstructs for a favorable implementation climate in a hospital organization were lacking and those that were identified were suboptimal. The inability to satisfy all the subconstructs seemed to be the consequence of insufficient resources and infrastructure within the current health system. A favorable implementation climate in a resource-limited environment is closely tied to the availability of health care resources and infrastructure.

Keywords: care pathway, implementation, health care, leadership, Caribbean, pressure ulcer, interprofessional collaboration

Introduction

A care pathway is “a complex intervention made up of mutual decision-making and organization of care processes for a well-defined group of patients during a well-defined period”.1 The aim of a care pathway, which often involves a series of stages, is to enhance the quality of care, through risk-adjusted patient outcomes, patient safety, and satisfaction with the optimal use of health care resources.1 Proponents of care pathways argue that they can facilitate the translation of established guidelines into local management protocols and if adjusted to local health care needs, can potentially aid the implementation of guidelines in resource-limited environments.2

In many countries, care pathways are increasingly seen as valuable tools for health care improvement, though most of the evidence supporting this has emerged from experiences within Europe and North America. While the reports from what we know demonstrate that local sociopolitical, cultural, and economic factors need to be considered when implementing care pathways, research investigating the effects of care pathways in resource-limited environments is sparse. Especially, on how to effectively implement care pathways within different contexts of health care systems and the conditions needed to engage professionals in the process.

Curaçao is a Dutch Caribbean island with a small population of 150,563 inhabitants.3 The St. Elisabeth Hospital (SEHOS) is the sole general hospital of Curaçao, and it provides services in all major clinical specialties. However, local politics, socioeconomic uncertainties, and rising costs of health care have resulted in a health care system that has over the years shifted its priority to focus more on containing costs and less in investing on process improvement and innovation.4 With the knowledge of this in mind, there was a perceived sense of urgency to turn things around and change the current health system to a value-based health care system.5 As a result, the health care improvement strategy that we chose focused on: 1) investing in workforce leadership development; and 2) defining, designing, and implementing innovative, health improvement interventions that will best serve the local situation. An implementation climate is an “absorptive capacity for change, shared receptivity of involved individuals to an intervention, and the extent to which use of that intervention will be rewarded, supported, and expected within their organization”.6 Current models of implementation climate describe the process as a system of interacting factors that reliably determine the organizational readiness for change.

In light of the perceived sense of urgency for change in the health care system, a number of measures were initiated at both the national ie, construction of a new hospital, as well as at the local levels to transform the health system in Curaçao ie, strategies to improve the organizational process and structure. Therefore, the focus of this study was to investigate those factors that defined the implementation climate within SEHOS in Curaçao. We chose a care pathway as our preferred strategic approach because we believed it would benefit the health improvement initiative within our context.

Methods

We designed a health care improvement project that was made up of two parts: 1) workforce leadership development through the implementation of a clinical leadership training program; and 2) health care quality improvement through the development of a decubitus ulcer care pathway. We selected a mixed team of health professionals to participate in this project all of whom were actively involved in the process of the chosen care pathway. The findings from previous research we conducted determined our choice for an interprofessional team.7 In that study, we identified that interprofessional teams that focused on the development of individual and collective leadership skills of its members helped foster capabilities needed to achieve sustainable health care systems and support the practical introduction of care pathways.

A participatory tool was used to assess the local factors and barriers that influenced the implementation climate for clinical care pathways as well as the effect of the intervention on quality improvement (Figure 1). The study focussed on the implementation climate in general and not specific for the ulcer care pathway, this way it could also serve as a basis for future projects. The interviews were conducted after the first leadership training but before the development of the care pathway by the interprofessional team.

The general focus of the evaluation in this project was diverse and included identifying the participants’ perceived level of leadership competency, their perceived appreciation of the training/workshop, a baseline measurement of the current implementation climate in hospital organization, as well as investigating the impact of the health improvement project over time. We chose to use a qualitative research approach for our investigation, because it would help us obtain the in-depth information we needed to understand what defined the hospital’s implementation climate prior to the development of the care pathway, as well as the circumstances under which the improvement initiative could be implemented.8 Therefore, the focus of the evaluation in this paper is the understanding of the implementation climate prior to the development and implementation of the care pathway.

Settings and participants

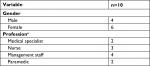

The fieldwork was conducted in May 2017 at SEHOS, Curaçao. To attain the study objectives, participants with different backgrounds/professions were included, with the aim of obtaining various perspectives on the current implementation climate in the hospital. A purposive sampling method was used to assure a variety in profession. We selected the respondents from the test group (n=25), who were trained to become health care leaders within the hospital. Table 1 contains the demographic characteristics of the participants. A total of ten participants participated in the study and the group consisted of nurses, doctors, management, and paramedics as shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Respondents’ demographics (n=10) Note: aOne participant had two functions within the organization. |

In-depth semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with the use of a preconstructed topic guide that explored the respondents’ personal views of the current implementation climate as well as of the organizational structure itself. The topic guide was based on existing literature and included questions on the following topics: 1) respondents’ role within change processes in the hospital; 2) the organizational climate and culture (which included the vision of the organization); and 3) leadership in the hospital.6 Due to the semi-structured nature of the topic guide, participants were encouraged to elaborate on their answers and additional questions were asked to clarify on certain topics. The interviews were held separately and lasted an average of 25 minutes (ranging from 7 to 35 minutes), nine interviews lasted between 20 and 35 minutes, and only one interview was shorter than expected due to the need to attend to an emergency by the participant (see Table 2). A separate group meeting was organized for the participants to reflect and discuss the preliminary findings, which served as a member check of the results and if they recognized and agreed with the preliminary data outcome. During this meeting no new themes were identified, and the participants agreed with the presented analysis.

| Table 2 Overview of the duration of interviews with the participants Note: aThis participant had an unexpected emergency to attend to and left prematurely for the operating theater. |

Analysis

All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. These transcripts served as a basis for the thematic content analysis, which aimed to report the critical elements in the responses and allowed a comparison and categorization of the various perspectives.8 We used the Atlas.ti computer software to construct coding schemes that were used to identify the (sub)themes.9 An inductive analysis process, with open codes, was used since currently little is known about the implementation climate at the Caribbean.10 The participants were able to review the preliminary findings of the analysis and had the opportunity to provide feedback on the data. They were able to verify whether the findings that they were shown truly emerged from the data. By going through this process, we expected that their feedback would contribute to the credibility of our research.10 All quotes were translated from Dutch into English and were used to support the identified themes from the analysis.11 The themes, explaining the current implementation climate included: 1) the attitude of staff toward policy changes; 2) vision of the organization; 3) collaboration; 4) transparency and communication; 5) personal development; and 6) resources.

Ethical considerations

All participants participated voluntarily and were informed about the objectives of the study by JB and AJD. Before the interviews were conducted, the participants were asked to read and sign a consent form. To ensure their confidentiality, the transcription of the interviews and data analysis were performed anonymously. Ethical approval was given by the SEHOS medical ethical board on March 1, 2017.

Results

In general, the analysis of the current factors influencing the implementation climate showed that participants felt the need toward introducing procedures and guidelines that meet the current state of the art of evidence-based medicine. They felt that current procedures did not align with the latest developments in their specific fields. We asked the participants what they expected from this project, in which health care workers would be trained in health leadership competencies and participate in designing a care pathway. Different expectations were described, all of them addressing the factors that influence the current implementation climate. Some of their expectations included that the project should contribute to defining a clear vision and serve as a blueprint for future policies. They expected that the project would serve as a foundation for good collaboration across all levels, and a good way to involve all stakeholders. Another expectation that was perceived positively was that the project would benefit the personal development of the participants. As an outcome, participants expressed the hope that the project would result in a specific protocol that would standardize care and overall health care improvement, as one of the respondents mentioned.

I think that once the care pathway is completed and implemented, with the necessary policies and guidelines in place, and together with the multidisciplinary approach, it will undoubtedly contribute to the quality of health care delivery in the hospital. [P5]

When it came to the implementation of procedures, the respondents showed a high sense of urgency, expressing that this had to be in place before completion of the construction of the new hospital. Participants mentioned they often sought for guidelines outside their hospital to use and even recruited the help of colleagues from abroad to keep their knowledge up to date. The participants highlighted many factors that influenced the implementation climate. These included the attitude of staff toward policy changes, the vision of the organization, collaboration, transparency and communication, personal development, and resources as factors that influenced the implementation climate. These factors also had several potential consequences and effects.

Attitude of staff to policy changes

Participants mentioned they sometimes noticed reluctance toward policy changes among staff on the working floor. Several reasons were found to be underlying of this reluctance. First of all, participants mentioned that negative experiences from the past shaped the current opinions of staff members toward policy changes. Second, experiences showed fear toward policy changes. Staff members feared that the new policy or regulation would give them more work in their daily routine or that the change would be negative on a personal level. Finally, participants mentioned that staff members often were stuck in their current daily routine and therefore simply not interested in new policy changes.

They are done with the changes. Nobody wants to. Not whether they want to. They are simply tired, they don’t believe it anymore, because several projects have been launched, but no progress has been made. Uh yeah, they simply don’t see why they should do it. [P5]

So, I think there are people who are afraid of changes. Maybe for their own sake or so, probably they think it will harm them or result in them having to change their work on the department for example, resulting in too much work, or too much administration or the feeling that somebody is watching them perform their duties. This of course it is not a bad thing. [P2]

Sometimes you see a disenchanted attitude among the professionals. You try to implement something, and you get a response like: yeah it has been like this for years and this is just the way we do it and we are in Curacao, so we are not going to change that. So, the mentality of the staff is often an issue. That is coherent with the fact that they are understaffed though. [P9]

The participants highlighted that hospital staff needs to feel involved in the policy forming process to create a positive attitude toward policy changes, which of course requires a supportive working environment.

Vision of the organization

Concerning the current vision of the organization, the participants expressed the following three opinions. First, they were unaware of the current vision of the hospital. Participants had no idea of what the long-term plans were as well as what the hospital expected of them. They experienced that a lack of transparency was responsible for the unawareness. Second, they mentioned that the current investments and policy changes revealed a lack of a long-term vision to support these investments. Last, participants mentioned that the vision of the board did not always align with their vision.

We do not have a long-term vision of the board of directors. It is just band-aid solutions. [P9]

The organization is open-minded towards changes; however, they do not know what they would like to change. For example, one could be open-minded, but if one does not know what it is that needs to change and how to achieve this, then in such a case, it is not a change, but just spinning around in circles. [P6]

Analysis showed that several underlying factors caused this negative view on the current long-term vision. A lack of communication and transparency from the hospital administrators was one of the reasons, which will be elaborated later. Next to that, a lack of medical knowledge and know-how among the management staff were viewed upon as a cause of the negative perception of the current vision. Participants mentioned that hospital administrators and senior management staff were often positioned too far from the routine of clinical practice, resulting in them not understanding the current issues in the frontline of care. Furthermore, they observed that some “team leads” in the department lacked the professional capacities to formulate a well-structured policy because they did not have the proper management training. Nevertheless, the participants emphasized that it was important to involve staff in the creation of a long-term vision and to communicate this transparently to all staff members.

Collaboration

The presence of effective collaboration was a significant factor influencing the current implementation climate. The participants perceived it as suboptimal on several levels: both horizontal, between the different wards, as vertical level, between the managers and the staff on the ground floor. They also viewed the collaboration between the different disciplines as suboptimal. Participants described difficulties in collaborating with other disciplines and mentioned that procedures and guidelines were often not synchronized among the different departments in the hospital, which resulted in a fragmented system.

Currently a protocol is made that needs the input of the relevant medical specialists. It’s like, I have addressed a few specialists a couple of times. And there is none to zero response. Yes, that’s, that is quite difficult. You just want someone, even just for a brief moment, but to actively get involved, but if people don’t do that. Yeah in that case, that makes it very difficult. [P4]

Well people, yeah, people around here are quite emotional. And well one person doesn’t, that one person doesn’t want to join if another is present. So you see this in all layers. Even among the doctors and nurses, the head nurse. There are conflicts. And everybody seems to forget that they work in the name of a foundation. You know what I mean? […]. So it is not your sole responsibility. You have to collaborate. And if you are not capable to collaborate you just have to find something else. And that is not always easy around here […]. Well if there is an issue. In other words, most people don’t look beyond the “person” to address issue, and at a particular point in time it becomes a personal conflict. [P3]

No, they [policies] don’t match and this also impedes your policy at the ward. So, we must work together to make sure they are coherent, like a flowchart. [P1]

The participants also mentioned examples of good collaboration, where they perceived support from other departments and disciplines. These networks were used to find ways to implement evidence-based medicine and to adjust and synchronize activities among the different disciplines and departments. They perceived great collaborations that involved all stakeholders as essential to achieve the implementation of successful changes or to find solutions for current issues. Participants expressed a desire to have more multidisciplinary meetings to gain new perspectives from different disciplines and feel involved in all aspects of patient care.

A better collaboration during multidisciplinary meetings is needed, with different disciplines. One needs to get one’s discipline involved in the meetings. Because often, yeah, often they forget us. Moreover, I think it is essential, that I am present (at the meetings), remember, I want to participate. [P8]

Transparency and communication

One of the central themes that came across from the analysis was a need for more transparency and communication. Participants were unsatisfied with the current transparency, and the current way innovations and policies were implemented. They felt they were not involved in the current decision-making process or did not get sufficient response to their initiatives to improve health care.

I do notice, that there is a select group of people higher up in the organization, who are behind closed doors, preparing some things, and then they tell us: changes are coming up, and the things will be thoroughly thought through and analyzed. However, I have not witnessed this yet, despite hearing about it for years. [P6]

Lack of transparency also caused a feeling that some procedures were unnecessarily bureaucratic. For instance, the health care professionals had written their guidelines to improve the health care on a specific topic. However, those protocols had first to be officially approved, which did not happen or resulted in delays for the implementation.

We are supposed to have protocols and guidelines. Meanwhile, some are stuck in the regulatory department, with the people who are supposed to approve the protocols before they are implemented […]. The protocols are just stuck there for no known the reasons. So, yeah, we are still waiting. In the meantime, one has to continue treating the patients. [P2]

The lack of transparency and communication led to unclarity about the current policies as well as losing credibility. Heads of departments even mentioned they did not inform their staff about new changes, because they were afraid that if the new policies were changing over and over, they would lose their credibility among their staff members.

There is no clarity, which leads to uncertainty among the staff (over time). As a supervisor, one wants to know what to communicate to one’s department, which can sometimes turn out to be frustrating. At one point, because of regular postponement, I decided to stop communicating with my staff about the date of supply of some needed materials and equipment, until they were finally delivered simply because of the risk of losing my credibility. [P10]

Personal development

Analysis of the experiences of the participants showed that another factor influencing the implementation climate in SEHOS was the (opportunity for) personal development. Participants mentioned that there was insufficient appreciation by their managers and a limitation in career possibilities as something that influenced their motivation. Another factor that became apparent was the lack of education and training possibilities. Participants expressed the desire to develop themselves but felt that they did not get the opportunities to attend courses or training sessions to gain more insight.

The career possibilities in this hospital are quite limited. Especially in the care department. So, at one point, one gets the feeling to have reached the ceiling for further professional growth. [P6]

Participants expressed the need for the hospital to pay more attention to their personal development. They perceived that training opportunities to acquire essential skills and knowledge needed to help them to stay up to date with current developments in the profession were insufficient. They argued that these limitations contributed to the perceived sense of high workload in their duties, not being able to meet set targets, and not having the capacity to implement health care improvement projects. Consequently, working on new policies was not considered to be a priority given these current circumstances.

We need the right people doing the right job. If you do not have those people, then you cannot meet the set targets. [P1]

While the participants highlighted the need for more investment in material resources and setting realistic targets, our analysis revealed that there was also a lot of improvisation and the use of creative ways to deal with the lack of resources.

Resources

Health care workers expressed resources as one of the barriers that prevented working on new policies and implementing innovations that could potentially improve the health care delivery in the hospital. The comments of the participants showed that human resources (staffing, both in numbers and competencies and skills), physical structures (infrastructure), and education were the significant determinants of resource shortage. Participants mentioned that often they were understaffed, as well as not always fully equipped or trained for the given tasks.

I need another internist with a specialty in infectious diseases. Unfortunately, there is a fixed quota to the number of internal medicine specialists that are allowed to work on the island. We have already exceeded that number which is another limitation so to say. In essence, we need an additional person, but because of all of the different rules hiring another specialist is quite tricky. [P4]

It is no longer doable. Patients have become more complicated. We have many surgeries a day, except on Friday and lately, we have had many temporary workers. Because they are primarily involved in the basic care, they cannot give the support (specialized care) we need in the surgery department, and that is not responsible care. [P1]

The respondents mentioned physical means, ie, material as another challenge in the current health care system on the island. The lack of funding expressed itself in a shortage of medicines, tools, and a lack of digital equipment. However, experiences of the participants showed that it was not always the lack of physical means, but also the improper allocation of the means that could result in a shortage.

Yes, patients should receive reliable care, but if you don’t have the means to provide the services sufficiently […] and if the staff needs to take courses and there is limited funding to attend these courses, then the process runs into jeopardy. Despite the fact that funds are limited, we still do a lot by being creative. For example, recycling materials and redesigning it for other purposes. [P3]

There are not enough decubitus matrasses. Meanwhile it is just a cheap investment. I heard that they just cost a hundred and fifty gulden (equivalent to 84 USD). That is apparently ten times cheaper than the treatment for a chronic decubitus wound. [P9]

Potential consequences/effects

All the previously mentioned factors had several consequences. Participants mentioned they had the idea that current policies were shortsighted. They felt that a lack of a long-term vision and a shortage in current resources were responsible for this, resulting in ad hoc solutions for current issues rather than finding a long-term solution. Experiences also showed that there was much unclarity due to the lack of transparency, which also led to the hospital administrators losing credibility among the staff members. Next to that, the participants also experienced some consequences themselves. Account of their experiences showed that they sometimes lost motivation and felt hopeless when it came to working on new policies that could aid in the health quality improvement. Other personal consequences included the feeling of suspicion toward all new policy implementations and not feeling connected to other departments: having an “us vs them” feeling. However, the reflected challenges also cause creativity among health care workers to find new ways in which they could still improve the current health care delivery. An overview of our findings is summarized in Table 3.

| Table 3 Matrix of the major themes and subthemes identified by participants |

Discussion

The aim of this study was to map out those factors that influenced the implementation climate in SEHOS. The in-depth interviews with health care workers and hospital administrative staff provided us with an insight into the influence of factors like the attitude of staff toward policy changes, vision of the organization, collaboration, transparency and communication, personal development, and resources on the implementation climate as shown in Figure 2. These factors appeared to be interrelated and were associated with several potential effects and consequences that included the potential loss of motivation among the staff, loss of creativity to solve issues, emergence of the feeling of “us” vs “them”, short-term solutions to problems, and a sense of suspicion/frustration among the staff members.

| Figure 2 Overview of the underlying factors, influencing the implementation climate and the perceived consequences of these factors. |

Comparison to existing literature

Our results reveal several factors underlying the implementation climate for health care interventions in SEHOS. Current diagnostic models comprise of six subconstructs that contribute to a favorable implementation climate: 1) tension for change; 2) compatibility; 3) relative priority; 4) organizational incentives and rewards; 5) goals and feedback; and 6) learning climate.6 When analyzing this, the current implementation climate in Curaçao is mainly affected by the subconstructs of compatibility, relative priority, organizational incentives and rewards, goals and feedback, and learning climate. Compatibility could be seen as the degree of tangible fit between meaning and values and how they align with own norms, values and perceived risks, and needs.6 Our results showed suboptimal compatibility, in the factor (vision of the organization), since the vision of the organization was, according to the participants, not always seen as a solid fit. This observation had some overlap with the subconstruct of relative priority, where the vision of the organization was also not always shared among the health care professionals, leading to different priorities and a different perception of the importance of the implementation and contributing to an unfavorable implementation climate. The lack of the subconstruct, organizational incentives, and rewards (associated with extrinsic incentives such as promotions, and performance) was reflected mainly in the underlying factors of personal development and resources. The participants expressed the feeling that they were not compensated or rewarded sufficiently for their inputs, and also, not offered learning opportunities. This could contribute to the sense of a less favorable implementation climate.6 Besides, the subconstruct of goals and feedback, which is described as “the level to which goals are communicated, acted upon, and fed back to the staff...”,6 the implementation climate was reflected through the factors communication and transparency. This factor described how the existing communication and transparency could potentially lead to an unfavorable implementation climate. These two factors could also be linked to the previously researched high-power distance and masculinity of organizational cultures in Curaçao, where the “less powerful” in society reflected a tendency to accept (and expect) the unequal distribution of power and the preference for achievement, heroism, and assertiveness as opposed to the need for cooperation, modesty, caring for the weak, and quality of life.12–14 The first subconstruct for a favorable implementation climate; tension for change ie, the degree to which stakeholders perceive the current implementation climate, was not per se reflected in the results of this study.6 Yet, the fact that all participants voluntarily signed up for the workshops and training, without receiving any financial or time compensation, could be a sign that the stakeholders perceived the current situation as intolerable and are in need for change. As a result, it does not inform us adequately, about its effects on the implementation climate for change.

The participants of this project were health professionals who underwent clinical leadership training and worked together as an interdisciplinary team to develop a care pathway. The expectations were that this process would contribute to the development of a new strategic vision that would serve as a blueprint for a favorable change in the subconstruct of compatibility and relative priority. The expected change would also enhance collaboration, which could lead to more transparency and therefore a more positive subconstruct of goals and feedback. Its contribution to personal development would also facilitate better organizational incentives and rewards, which although considered extrinsic as personal development, were also partially intrinsic.

In our model, we chose for the creation of a care pathway as these have been proven to be beneficial in improving the quality and safety of health care practices.15 As this study focused on how to identify and overcome barriers hindering a healthy implementation climate, it probably also explains the reason for the respondent’s strong emphasis on the limiting factors we identified in the themes of our result. We anticipated that the process would involve health care professionals from different sectors which could trigger or enable reflections in the participants and help (re-)define professional roles within a local context. Our choice of an interprofessional health improvement project was aimed at developing the clinical leadership capabilities of a mixed team of health care professionals while engaged in the development of a care pathway of their choice. This approach was also expected to foster participation and accountability in the implementation process as shown by our group, and has also been shown as a successful quality improvement initiative in previous research in developed countries.16 Although most of the focus in the literature is on clinician-related barriers, several barriers reported in our study align with some of these barriers such as lack of staff involvement, available resources, and insufficient staff.17 Our findings demonstrate that in the transformation of health care systems, a sound understanding of the organizational culture (implementation climate) and the quality of the workforce (clinical leadership abilities) are essential determinants for success.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings from this study show that some of the positive subconstructs for a favorable implementation climate in the hospital organization we studied were lacking, while some of those that were identified were suboptimal. The lack of compatibility, relative prioritization, and lack of organizational incentives and rewards all demonstrate this. In addition, the lack of clearly defined goals and feedback pose potential threats to future projects and innovations. The inability to satisfy all the subconstructs seemed to be the consequences of the lack of sufficient resources and infrastructure in the current health system and an estranged organizational culture where the flow of communication is not optimal, and the organization’s vision is not transparent and clear to its employees. All these factors should be considered and if possible mitigated or improved to get favorable outcomes in new projects and improve the health care overall. The participants’ experience of the health care leadership training and interdisciplinary care pathway development showed that our project could mitigate some of these unfavorable factors. Finally, it is important to mention that on completion of this study, the hospital embraced some of the recommendations for change and solicited the support of a professional human resource development company to guide the implementation of the pressure ulcer care pathway as well as provide administrative support to the health care professionals. The participants of this clinical leadership project are now a group of “process changers” who are championing health care improvement within the organization. As the project progresses, we shall be monitoring the implementation process and searching to understand the consequences and effects on health care delivery as they emerge.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Vanhaecht K, De Witte K, Depreitere R, et al. Development and validation of a care process self-evaluation tool. Health Serv Manage Res. 2007;20(3):189–202. | ||

Campbell H, Hotchkiss R, Bradshaw N, Porteous M. Integrated care pathways. BMJ. 1998;316(7125):133–137. | ||

Central Bureau of Statistics C. First results Census 2011 – Curacao. Demography of Curacao: Publications series Census 2011. Available from: https://www.cbs.cw/website/2011-census_3226/item/demography-of-curacao-publication-series-census-2011_757.html. Published 2014. Accessed November 10, 2018. | ||

Busari JO, Duits AJ. The strategic role of competency based medical education in health care reform: a case report from a small scale, resource limited, Caribbean setting. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):13. | ||

Busari JO. Quality Requirements of Competency-Based Medical Care in the New Integration Process of Medical Specialists in Curaçao. Willemstad, CW: NASKHO; 2012. | ||

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. | ||

Busari JO, Moll FM, Duits AJ. Understanding the impact of interprofessional collaboration on the quality of care: a case report from a small-scale resource limited health care environment. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10(227):227–234. | ||

Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nicholls CM, Ormston R. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide For Social Science Students and Researchers. London: SAGE; 2013. | ||

Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. London: SAGE; 2004. | ||

Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. | ||

Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ Inform. 2004;22(2):63–75. | ||

Busari JO, Verhagen EA, Muskiet FD. The influence of the cultural climate of the training environment on physicians’ self-perception of competence and preparedness for practice. BMC Med Educ. 2008;8(1):51. | ||

Hofstede G, Peterson MF. National values and organizational practices. In Ashkanasy NM, Wilderom CPM, Peterson MF, editors. Handbook of organizational culture and climate. London: Sage; 2000:401–405 | ||

Hofstede G. Dimensions of National Cultures in Fifty Countries and Three Regions. Lisse: Swets and Zeitlinger; 1983. | ||

Schrijvers G, van Hoorn A, Huiskes N. The care pathway: concepts and theories: an introduction. Int J Integr Care. 2012;12(Spec Ed Integrated Care Pathways):e192. | ||

Kaplan HC, Brady PW, Dritz MC, et al. The influence of context on quality improvement success in health care: a systematic review of the literature. Milbank Q. 2010;88(4):500–559. | ||

Evans-Lacko S, Jarrett M, Mccrone P, Thornicroft G. Facilitators and barriers to implementing clinical care pathways. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):182. |

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.