Back to Journals » Drug Design, Development and Therapy » Volume 10

Voiding dysfunction in patients with nasal congestion treated with pseudoephedrine: a prospective study

Authors Shao I , Wu C , Tseng H, Lee T, Lin Y , Tam Y

Received 19 March 2016

Accepted for publication 4 May 2016

Published 19 July 2016 Volume 2016:10 Pages 2333—2339

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S108819

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Wei Duan

I-Hung Shao,1,* Chia-Chen Wu,2,* Hsiao-Jung Tseng,3 Ta-Jen Lee,2 Yu-Hsiang Lin,4 Yuan-Yun Tam5

1Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Lotung Poh-Ai Hospital, Yilan County, 2Department of Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung University, 3Biostatistical Center for Clinical Research, Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan City, 4Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan City, 5Department of Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Lotung Poh-Ai Hospital, Yilan County, Taiwan

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Background: Pseudoephedrine is a sympathomimetic drug widely used as a nasal decongestant. However, it can cause adverse effects, such as voiding dysfunction. The risk of voiding dysfunction remains uncertain in patients without subjective voiding problems.

Methodology: We prospectively enrolled patients with nasal congestion who required treatment with pseudoephedrine from May to August 2015. All patients denied concomitant subjective voiding problem. The International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) questionnaire was used to evaluate voiding function before and 1 week after the pseudoephedrine treatment. The results of the IPSS questionnaire were analyzed as the total (IPSS-T), voiding (IPSS-V), storage (IPSS-S), and quality of life due to urinary symptom scores.

Results: We enrolled 131 males with a mean age of 42.0±14.3 years. The IPSS-T, IPSS-V, and IPSS-S scores slightly increased after the medication (IPSS-T increased from 6.49 to 6.77, IPSS-V from 3.33 to 3.53, and IPSS-S from 3.17 to 3.24). The quality of life due to urinary symptom score nonsignificantly decreased from 2.02 to 1.87. We observed that older age and a higher premedication IPSS-V score yielded significant differences (P<0.05) for subclinical voiding dysfunction and unchanged voiding function. In patients aged ≥50 years, the IPSS-T, IPSS-V, and IPSS-S scores significantly increased after the pseudoephedrine treatment (IPSS-T increased from 9.95 to 11.45, IPSS-V from 5.38 to 6.07, and IPSS-S 4.57 to 5.38), whereas the quality of life due to urinary symptom score nonsignificantly decreased from 2.71 to 2.48 (P=0.057). In patients aged <50 years, all scores did not significantly differ.

Conclusion: Pseudoephedrine treatment for nasal congestion requires extra precautions in males >50 years, even without subjective voiding symptoms.

Keywords: pseudoephedrine, nasal congestion, voiding dysfunction, IPSS

Introduction

Pseudoephedrine is a sympathomimetic drug belonging to phenethylamine and amphetamine chemical classes and is widely used as a nasal decongestant. It exerts a decongestant effect on the swollen nasal mucosa of patients with chronic or acute rhinitis; however, it causes adverse effects, such as urinary retention in males, because of its systemic action on α-adrenergic receptors.1 Although pseudoephedrine generally has little effect on voiding in young patients, its actual effect on voiding function remains unclear.

Urology clinics and emergency departments are sometimes required to deal with males who experience dysuria, incomplete voiding, or acute urinary retention after taking pseudoephedrine. Most of these patients are aged over 50 years, and some may have coexisting benign prostate hyperplasia, which they may not report to their doctor. Other patients may be relatively younger or may not report any history of voiding dysfunction.

Although pseudoephedrine is labeled as requiring extra caution while administration in males with benign prostate hyperplasia,2,3 no other specific precautions regarding patient characteristics, such as age, are mentioned.

Some studies have reported about the adverse effects of pseudoephedrine, such as urinary retention in children and adult patients.1–5 However, these studies have not provided any information regarding the age dependency of such adverse effects. To the best of our knowledge, no study has yet investigated the effect of pseudoephedrine on voiding function in asymptomatic males.

In this study, we used the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) questionnaire to evaluate the effects of pseudoephedrine on voiding function in asymptomatic males who received pseudoephedrine for nasal congestion treatment.

Patients and methods

Participants

The Institutional Review Board of Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital approved this prospective study (registration number 104-4791B). Between May and August 2015, we recruited males with acute or chronic rhinitis who visited our outpatient department for evaluation. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment in this study. Because all patients complained of nasal obstruction, we considered prescribing pseudoephedrine for symptom relief. We excluded women, males who self-reported voiding problems, males who were already receiving medications for voiding dysfunction, and males who were currently receiving any medication that could affect voiding function (eg, antihistamines that can inhibit the bladder contractility).

Measurement of lower urinary tract symptoms

We used the IPSS questionnaire to evaluate voiding dysfunction in the patients. The IPSS is a basic questionnaire widely used by urologists. It contains the seven-item American Urological Association (AUA) Symptom Index and one question on quality of life (QoL), which is used to evaluate lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in males, such as the benign prostate hyperplasia-related voiding problem. The seven-item AUA Symptom Index, developed and psychometrically validated by an AUA Measurement Committee in 1992, reliably assesses the severity of LUTS and is responsive to changes in the treatment.6 In 1993, the World Health Organization adopted the eight-item IPSS, which uses the same seven questions assessing the LUTS severity as the AUA Symptom Index, along with an eighth disease-specific QoL question that assesses severity associated with LUTS.7 A study reported the reliability of this questionnaire for the evaluation of women with lower urinary tract dysfunction.8 The seven questions are divided into the following two parts: IPSS voiding (IPSS-V) scores and IPSS storage (IPSS-S) scores.9 The IPSS-V scores consist of weak stream, intermittency, straining, and feeling of incomplete bladder emptying, whereas the IPSS-S scores consist of frequency, urgency, and nocturia. Each scoring ranges from 1 to 5 for a total of maximum 35 points. The eighth question on QoL is assigned a score of 1 to 6. The detailed information is listed in Table 1.

Study protocol

Pseudoephedrine was prescribed to all the patients enrolled to treat their nasal congestion. We prescribed oral pseudoephedrine sulfate 120 mg bid for 1 week to every patient. The patients were asked to complete the IPSS questionnaire before and 1 week after taking oral pseudoephedrine. The results of the questionnaire were analyzed as the IPSS total (IPSS-T), IPSS-V, IPSS-S, and QoL due to urinary symptoms (QoL-US). We defined an increased IPSS-T score after receiving the medication as subclinical worsening of voiding function.

Statistical analysis

All premedication parameters were analyzed using the independent t-test to ascertain significant predictors. We used the paired samples t-test to analyze premedication and postmedication parameters in the overall patients and in age-stratified groups (<50 and ≥50 years). The general additive model was used to examine the relationship between age and deteriorated voiding after medication. Most statistical analyses were performed on a personal computer by using the statistical package SPSS for Windows (Version 17.0) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and the R software (Version R 2.14.0; R & R, Auckland, New Zealand) for general additive models.

Results

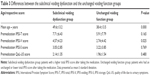

In total, 131 patients completed the questionnaire before and 1 week after receiving pseudoephedrine. The average age of the patients was 42.0±14.3 years. The scores obtained in the IPSS questionnaire before and after the medication are listed in Table 2. The IPSS-T, IPSS-V, and IPSS-S scores slightly increased after the medication; however, the increase was not significant (IPSS-T increased from 6.49 to 6.77, IPSS-V from 3.33 to 3.53, and IPSS-S from 3.17 to 3.24). The QoL-US score nonsignificantly decreased from 2.02 to 1.87. Among the 131 patients, 52 (39.7%) had lower IPSS-T scores after the medication, whereas 37 (28.2%) and 42 (32.1%) had unchanged or higher scores. The numbers and percentages of the patients with changes (increased, unchanged, or decreased) in the IPSS-V, IPSS-S, and QoL-US scores after the treatment with pseudoephedrine are listed in Table 2.

We divided all the patients into two subgroups by defining an increased IPSS-T score after pseudoephedrine treatment as the subclinical worsening of voiding function and an unchanged or decreased IPSS-T score as unchanged voiding function. The independent t-test was used to analyze differences in age and premedication IPSS-T, IPSS-V, IPSS-S, and QoL-US scores between these two subgroups. The results are listed in Table 3. We observed that age and premedication IPSS-V score significantly differed between the subclinical voiding dysfunction and unchanged voiding function subgroups (P<0.05). The mean age and premedication IPSS-V score in the subclinical voiding dysfunction subgroup were 49.6 years and 4.57, respectively, and those in the unchanged voiding function subgroup were 38.4 years and 2.74, respectively.

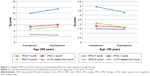

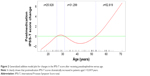

The results of the paired samples t-test are listed in Table 4. The IPSS-T, IPSS-V, IPSS-S, and QoL-US scores did not significantly differ before and after the medication in the overall patients. However, the scores differed after stratifying the patients according to their age, those ≥50 and <50 years. In the ≥50-year group, the IPSS-T, IPSS-V, and IPSS-S scores significantly increased after the medication (IPSS-T increased from 9.95 to 11.45, IPSS-V from 5.38 to 6.07, and IPSS-S from 4.57 to 5.38), whereas the QoL-US score nonsignificantly decreased from 2.71 to 2.48 (P=0.057). In the <50-year group, all the scores decreased but not significantly. The difference in the symptom score change between the two age-stratified groups is presented in Figure 1. Of the 131 patients, the IPSS-T score after the medication increased in 42 patients (32.1%). After the treatment, 51.8% of the 56 patients in the ≥50-year group and only 17.3% of the 75 patients in the <50-year group experienced subclinical voiding dysfunction. The general additive model plots revealed the changes associated with deteriorated voiding function in different age groups (Figure 2). Most patients younger than 52.8 years exhibited no change or slight improvement in voiding function after the medication. By contrast, most patients older than 52.8 years exhibited deterioration in voiding function after the medication, and the difference increased with age.

Throughout the study period, three of the 131 patients, aged 29, 51, and 62 years, respectively, experienced symptomatic dysuria and visited urological clinics. No patients experienced acute urinary retention during the survey. All dysuria symptoms improved after pseudoephedrine discontinuation.

Discussion

Pseudoephedrine is widely used for treating congestion associated with allergies. Its principal mechanism of action relies on its direct effect on the adrenergic receptor system.10,11 The vasoconstriction produced by pseudoephedrine is believed to be principally an α-adrenergic-receptor response.12 The α-adrenergic receptors are located on muscles lining the walls of blood vessels, and when these receptors are activated, the muscles contract, causing the constriction of blood vessels. In addition, pseudoephedrine acts on β2-adrenergic receptors to induce relaxation of smooth muscles in the bronchi.10,11 Along with its therapeutic effect on nasal congestion, pseudoephedrine produces adverse effects, such as restlessness, nervousness, dizziness, stomach pain, vomiting, weakness, hallucination, palpitation, difficulty in breathing, and urinary retention.

The main cause of urinary retention or dysuria after the pseudoephedrine treatment is the effect of pseudoephedrine on α1A- and β-adrenoceptors. The α1A-subtype is highly expressed and promotes contraction of the bladder neck, urethra, and prostate to enhance the bladder outlet resistance, particularly in older males with enlarged prostates. The β-subtype mediates the relaxation of smooth muscles in the bladder.13 The main effect of pseudoephedrine on the lower urinary tract tends to maintain a continent bladder. Pseudoephedrine is effective in the treatment of certain forms of incontinence.14 In addition, an animal study reported clinical improvement in female incontinent dogs after pseudoephedrine treatment, despite the lack of statistically significant changes in urodynamic variables.15 By contrast, pseudoephedrine failed to treat the incontinent bladder in primary nocturnal enuresis in children.16

In 1928, an adult patient was first reported to suffer from voiding difficulty during pseudoephedrine treatment in Boston,4 which was followed with reports on the first pediatric cases of urinary retention after pseudoephedrine treatment in 1977.1,17 Since the first case, pseudoephedrine-related dysuria or urinary retention has occasionally been reported in urological or emergency departments. Most patients can be managed properly with urethral catheterization and pseudoephedrine discontinuation. No long-term sequelae have been reported. Urinary retention can be detected at lower doses of pseudoephedrine; however, few cases have been reported.18 Therefore, although pseudoephedrine is contraindicated for patients with urinary retention and should be administered with caution in patients with bladder outlet obstruction,2,17 it is still prescribed as a safe decongestant for patients without voiding problems.

In this study, we investigated changes in voiding function after pseudoephedrine treatment in males without coexisting voiding dysfunction. In our study, only 2.3% of the patients experienced symptomatic dysuria and required further management after receiving pseudoephedrine. However, among the patients who did not self-report voiding dysfunction, ~30% had increased IPSS-T scores, defined here as subclinical voiding dysfunction. Voiding dysfunction is significantly correlated with age in males, and the prostate enlargement has a crucial role.18 Thus, we divided our patients into age-stratified groups. The percentage of voiding dysfunction increased with age and increased to more than 50% (51.8%) in patients aged >50 years; it was only 17.3% in patients aged <50 years. This result suggested that older age is a potential risk factor for pseudoephedrine-related dysuria or urinary retention.

By dividing the patients into subclinical voiding dysfunction and unchanged voiding dysfunction subgroups, we observed that older patients and those with higher premedication IPSS-V scores (poor baseline voiding function) were more likely to have subclinical voiding deterioration. Such results imply that apart from older age, patients with undiagnosed lower urinary tract disease may develop subclinical voiding dysfunction and even clinical dysuria during pseudoephedrine treatment. The IPSS-T score consists of IPSS-V and IPSS-S scores; the former represents the voiding function and the latter represents the storage function. Pseudoephedrine causes contraction of the bladder neck, urethra, and prostate to enhance the bladder outlet resistance, which might impair patients’ voiding ability. This is consistent with our result that compared with a higher IPSS-S score, a higher IPSS-V score is a more favorable risk predictor of subclinical voiding dysfunction in patients receiving pseudoephedrine.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations, which are as follows: 1) we analyzed only males in this study; thus, whether pseudoephedrine exerts a similar effect in women requires further evaluation; 2) subclinical voiding dysfunction does not indicate a need for further medical assistance; therefore, examination of the number of patients requiring assistance and relevant associations will require a large sample size; 3) we recruited patients who received oral pseudoephedrine at a standard dosage for 1 week; thus, whether the outcomes differ at varying doses or durations remains unclear; and 4) the IPSS questionnaire only represents the subjective feeling of voiding problem; therefore, objective examinations, such as uroflowmetry and urodynamic study, are required to investigate the actual effect of pseudoephedrine on patients’ voiding function.

Conclusion

Although pseudoephedrine is often relatively safe in younger males and seldom requires further medical assistance, it might result in subclinical voiding dysfunction in older males. Treatment with pseudoephedrine requires extra precautions in males aged >50 years and in those with coexisting voiding symptoms.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the Biostatistical Center for Clinical Research of Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CLRPG3D0042).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Glidden RS, DiBona FJ. Urinary retention associated with ephedrine. J Pediatr. 1977;90:1013–1014. | ||

Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006. | ||

Boston LN. Dysuria following ephedrine therapy. Med Times. 1928;56:94–95. | ||

Gatti JM, Perez-Brayfield M, Kirsch AJ, Smith EA, Massad HC, Broecker BH. Acute urinary retention in children. J Urol. 2001;165(3):918–921. | ||

American Medical Association, AMA Department of Drugs. AMA Drug Evaluations. Littleton, MA: PSG Publishing Co., Inc; 1977:627. | ||

Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549–1557. | ||

Cockett ATK, Khoury S, Aso Y, et al. editors. The 2nd International Consultation on BPH. Jersey, Channel Islands: Scientific Communication International, Ltd; 1993. | ||

Hsiao SM, Lin HH, Kuo HC. International prostate symptom score for assessing lower urinary tract dysfunction in women. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(2):263–267. | ||

Cockett A, Aso Y, Denis L, et al. Recommendation of the International Consensus Committee concerning: 1. prostate symptom score and quality of life assessment. In: Cockett ATK, Khoury S, editors. Presented at: The 2nd International Consultation on Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH), Paris; June 27–30; 1993. Jersey: Channel Island, Scientific Communication International Ltd; 1994:553–555. | ||

Thomson/Micromedex. Drug Information for the Health Care Professional. Volume 1, Greenwood Village, CO: Thomson Micromedex; 2007:2452. | ||

Drew CD, Knight GT, Hughes DT, Bush M. Comparison of the effects of D-(−)-ephedrine and L-(+)-pseudoephedrine on the cardiovascular and respiratory systems in man”. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1978;6(3):221–225. | ||

Michel MC, Vrydag W. α1-, α2- and β-adrenoceptors in the urinary bladder, urethra and prostate. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147(Suppl 2):S88–S119. | ||

Hanes A, Lee Demler T, Lee C, Campos A. Pseudoephedrine for the treatment of clozapine-induced incontinence. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(4):33–35. | ||

Byron JK, March PA, Chew DJ, DiBartola SP. Effect of phenylpropanolamine and pseudoephedrine on the urethral pressure profile and continence scores of incontinent female dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21(1):47–53. | ||

Gelotte CK, Prior MJ, Gu J. A randomized, placebo-controlled, exploratory trial of Ibuprofen and pseudoephedrine in the treatment of primary nocturnal enuresis in children. Clin Pediatr. 2009;48:410–419. | ||

Shah R, McGrath KG. Chapter 6: Nonallergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33(Suppl 1):S19–S21. | ||

Soyer T, Göl IH, Eroğlu F, Çetin A. Acute urinary retention due to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride in a 3-year-old child. Turk J Pediatr. 2008;50(1):98–100. | ||

Boyle P, Robertson C, Mazzetta C, et al; the UrEpik Study Group. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in men and women in four centres. The UrEpik study. BJU Int. 2003;92(4):409–414. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.