Back to Journals » Drug Design, Development and Therapy » Volume 11

Protective role of quercetin against manganese-induced injury in the liver, kidney, and lung; and hematological parameters in acute and subchronic rat models

Authors Bahar E , Lee GH, Bhattarai KR, Lee HY, Kim HK, Handigund M, Choi MK, Han SY, Chae HJ, Yoon H

Received 13 June 2017

Accepted for publication 25 July 2017

Published 5 September 2017 Volume 2017:11 Pages 2605—2619

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S143875

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr James Janetka

This paper has been retracted

Entaz Bahar,1 Geum-Hwa Lee,2 Kashi Raj Bhattarai,2 Hwa-Young Lee2 Hyun-Kyoung Kim,2 Mallikarjun Handigund,3 Min-Kyung Choi,2 Sun-Young Han,1 Han-Jung Chae,2 Hyonok Yoon1

1College of Pharmacy, Research Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, 2Department of Pharmacology, Medical School, Chonbuk National University, 3Department of Laboratory Medicine, Chonbuk National University Hospital, Jeonju, Republic of Korea

Abstract: Manganese (Mn) is an important mineral element required in trace amounts for development of the human body, while over- or chronic-exposure can cause serious organ toxicity. The current study was designed to evaluate the protective role of quercetin (Qct) against Mn-induced toxicity in the liver, kidney, lung, and hematological parameters in acute and subchronic rat models. Male Sprague Dawley rats were divided into control, Mn (100 mg/kg for acute model and 15 mg/kg for subchronic model), and Mn + Qct (25 and 50 mg/kg) groups in both acute and subchronic models. Our result revealed that Mn + Qct groups effectively reduced Mn-induced ALT, AST, and creatinine levels. However, Mn + Qct groups had effectively reversed Mn-induced alteration of complete blood count, including red blood cells, hemoglobin, hematocrit, mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, platelets, and white blood cells. Meanwhile, the Mn + Qct groups had significantly decreased neutrophil and eosinophil and increased lymphocyte levels relative to the Mn group. Additionally, Mn + Qct groups showed a beneficial effect against Mn-induced macrophages and neutrophils. Our result demonstrated that Mn + Qct groups exhibited protective effects on Mn-induced alteration of GRP78, CHOP, and caspase-3 activities. Furthermore, histopathological observation showed that Mn + Qct groups effectively counteracted Mn-induced morphological change in the liver, kidney, and lung. Moreover, immunohistochemically Mn + Qct groups had significantly attenuated Mn-induced 8-oxo-2´-deoxyguanosine immunoreactivity. Our study suggests that Qct could be a substantially promising organ-protective agent against toxic Mn effects and perhaps against other toxic metal chemicals or drugs.

Keywords: manganese, quercetin, liver, kidney, lung, hematological parameters

Introduction

Manganese (Mn) is a mineral element that is both nutritionally essential and potentially toxic.1 In a number of physiologic processes, Mn plays an important role as an element of various enzymes and an activator of other enzymes, like Mn superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD), the principal antioxidant enzyme in mitochondria.2 Mn is potentially toxic and especially neurotoxic, which leads to a Parkinson’s disease-like syndrome called manganism.3,4 Mn causes toxic effects mainly in the brain, and also produces toxicity in liver, lungs, and heart, as well as reproductive organs.5–8 Mn is metabolized in the liver; therefore, excessive amounts may cause liver toxicity.9,10 Mn can cause an inflammatory response in the lungs, with clinical symptoms including cough, acute bronchitis, and decreased lung functions.11,12 Our previous study showed that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and stress-mediated apoptosis involved in Mn neurotoxicity, while 3-, 4-, or 5-aminosalicylic acids and polyphenolic extract of Euphorbia supina attenuate this effect.13–16

Flavonoids are phytophenolic compounds with strong antioxidant effects that function against oxidative stress.17 The flavonoid quercetin (Qct; 3,3′,4′,5,7-pentahydroxyflavone) is a typical polyphenolic compound found ubiquitously in fruit, vegetables, nuts, and plant-origin beverages like tea and wine.17 A number of studies have shown that Qct exhibits potential benefits for human health, due to its antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antiviral, antiulcerogenic, cytotoxic, antineoplastic, mutagenic, antioxidant, antihepatotoxic, antihypertensive, hypolipidemic, and antiplatelet properties.18–21 Qct blocks both the cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase pathways at relatively high concentrations, while at lower concentrations the lipoxygenase pathway is the primary target of inhibitory anti-inflammatory activity.22 Qct has been reported to reduce both oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity.23,24 Qct also plays a protective role in lead-induced inflammatory responses in rat kidney through the reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated MAPK and NFκB pathways.25 Qct has a protective effect against acrylamide-induced oxidative stress in rats.26 Recently, the protective role of Qct against hemotoxic and immunotoxic effects of furan in rats was reported.27 Qct has protective effects against hepatic injury by increasing plasma antioxidant capacity.28,29 Qct has been reported as radioprotective in mice lung via suppression of NFκB and MAPK pathways.30 Therefore, we investigated the protective effects of Qct against Mn-induced toxicity in the liver, kidney, and lung and hematological parameters in acute and subchronic rat models.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Seven-week-old Sprague Dawley male rats weighing 220–250 g each were purchased from Damool Science (Daejeon, South Korea). They were kept in clean and dry polypropylene cages on a 12-hour light–dark cycle at 25°C±2°C and 45%–55% relative humidity in the animal house of the Pharmacology Department, Chonbuk National University. The rats were fed a standard laboratory diet and water ad libitum. After a week of adaptation, the rats were randomly divided into four groups. The protocol used for this study in the rat as an animal model was carried out with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee (IACUC), and approval was gained from the ethical committee of Chonbuk National University (CBNU 2016-45).

Acute treatment

The rats were divided into four groups of six rats each. Rats in group 1 (control group) were injected intraperitoneally (IP) with 0.3 mL of normal saline solution (the solvent for Mn). Rats in group 2 (the Mn group) were injected IP with 0.3 mL of MnCl2 (100 mg/kg body weight) in normal saline for 4.5-hour exposure in a single dose. Rats in group 3 (the Mn + Qct25 group) were administered MnCl2 (100 mg/kg in normal saline) by injection IP after administration of Qct orally (per os [PO]; 25 mg/kg in normal saline) for 2.5 hours. Rats in group 4 (the Mn + Qct50 group) were administered MnCl2 (100 mg/kg in normal saline) by injection IP after administration of Qct PO (50 mg/kg in normal saline) for 2.5 hours. The rats were decapitated after 4.5 hours of injection IP, and blood samples were obtained for biochemical and hematological analyses. Liver, kidney, and lung specimens were fixed in 4% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin.

Subchronic treatment

A subchronic in vivo assay was performed according to the following protocol. Rats were divided into four groups of six rats each. Group 1 (control group) was treated with normal saline solution (every 24 hours for 8 days). Group 2 (Mn group) was administered eight doses of MnCl2 (15 mg/kg in normal saline) by injection IP every 24 hours for 8 days. Group 3 (Mn + Qct25 group) was administered eight doses of MnCl2 (15 mg/kg in normal saline) by injection IP after administration of Qct PO (25 mg/kg in normal saline) every 24 hours for 8 days. Group 4 (Mn + Qct50 group) was administered eight doses of MnCl2 (15 mg/kg in normal saline) by injection IP after administration of Qct PO (50 mg/kg in normal saline) every 24 hours for 8 days. The rats were killed at the end of the tests. Blood samples were obtained for biochemical and hematological analyses. Liver, kidney, and lung specimens were fixed in 4% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin.

Biochemical assays

ALT, AST, and creatinine levels were assessed using detection kits (Jiancheng Institute of Biotechnology, Nanjing, China), based on the manufacturer’s instructions.

Hematological studies

Measurement of hematological parameters

An animal blood counter (ABX; Horiba, Kyoto, Japan) was used to analyze the hematological parameters red blood cells (RBCs), hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (Hct), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), MCH concentration (MCHC), platelets, and white blood cells (WBCs). Analyses were carried out based on standard methods.54

Differential counts of white blood cells

Blood samples were analyzed for differential WBC counts, including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, according to standard methods using the ABX.

Preparation of peripheral blood smears for visualization of neutrophils and macrophages

Blood neutrophils and macrophages were visualized by peripheral blood smears.58 A blood film or peripheral blood smear is a thin layer of blood smeared on a glass microscope slide and then stained in such a way as to allow the various blood cells (BCs) to be examined microscopically. Briefly, blood films were made by placing a drop of blood on one end of a slide and using a spreader slide to disperse the blood over the slide’s length. The slides were left to air-dry, after which the blood was fixed to the slide by immersing it slightly in methanol. After fixation, the slide was stained to distinguish the cells from one another. Diff-Quik, a commercial Romanowsky stain variant, was used to stain rapidly and differentiate a variety of smears, commonly blood and nongynecological smears, including those of fine-needle aspirates.59–61 Briefly, dipped peripheral blood smears were slid into fixative reagent (triarylmethane dye and methanol), then slides dipped into stain solution 1 (eosin G in phosphate buffer), followed by stain solution 2 (thiazine dye in phosphate buffer), and excess was allowed to drain after each dip. Slides were rinsed in distilled water (pH 7.2) and allowed to dry in air, then visualized under microscopy (Eclipse E600; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Western blot analysis

Proteins extracted from tissues (80 μg) were analyzed by Western blot. Briefly, total proteins were extracted and protein concentrations determined using a bicinchoninic acid kit (Intron Biotechnology, Seongnam, South Korea). Protein samples were separated on 10% and 12% polyacrylamide gels and electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) in a semidried environment. Blots were blocked by 5% defatted milk in Tris buffer containing 0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated with primary antibodies: anti-GRP78 (1:1,000, SC-13539; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), anti-CHOP (1:1,000, L63F7, 2895s; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1:1,000, Asp175, 9661s; Cell Signaling Technology), and β-actin (A5441; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, the blots were incubated with antimouse (#115-035-003; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA), antigoat (SC-2020; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and/or antirabbit (SC-2004; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 hour. Then, blots were developed with EZ-WestLumi Plus solution (Atto, Tokyo, Japan) and analyzed with Ez-Capture ST (Atto).

Collection of tissue slices

The rats were deeply anesthetized with ketamine and perfused transcardially with 100 mL normal saline (0.9%). Liver, kidney, and lung specimens were fixed in 4% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections (14 μm) from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were cut using a microtome (RM2125 rotary; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and collected on silane-coated slides (Muto Pure Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) for histology and immunohistochemistry and stored at −70°C.

Histological assays

Liver, kidney, and lung samples were fixed in formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned. Liver, kidney, and lung sections were stained with H&E for routine histological examination. Pathological changes were viewed under light microscopy after staining, and images taken by differential interference contrast inverted microscopy (Nikon) equipped with micromanipulators (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemical staining of 8-OHdG

Paraffin-fixed liver, kidney, and lung slices were sectioned, deparaffinized, and rehydrated, and antigen retrieval was performed with Dako retrieval solution (pH 6) in a microwave oven for 30 minutes. Dako peroxidase-blocking solution was used to block endogenous peroxidase activity for 10 minutes. Dako protein-blocking solution was used to block aspecific protein binding, and tissues were treated with mouse polyclonal anti-8-OHdG (1:500, N45.1, ab48508; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Subsequently, these were incubated with biotinylated goat antimouse (1:30, D 0314; Dako) immunoglobulins and later visualized with substrate chromogen (K3464; Dako), followed by hematoxylin and mounted with aqueous mount medium. The sections were dehydrated and placed under coverslips, viewed under microscopy, and images taken with differential interference contrast inverted microscopy equipped with micromanipulators.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means ± SD, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test was used for statistical analysis using SPSS software (version 16). P<0.01 and P<0.001 were considered significant.

Results

Effect of Qct on blood biochemical parameters in Mn-treated rats

Mn treatment resulted in significant (P<0.001) increases in ALT, AST, and creatinine levels when compared with controls in acute (Figure 1) and subchronic (Figure 2) rats. Interestingly, Qct pretreatment significantly (P<0.01 or 0.001) reduced ALT (Figures 1A and 2A), AST (Figures 1B and 2B), and creatinine (Figures 1C and 2C) levels relative to the Mn group.

Effect of Qct on hematological parameters

Effect of Qct on complete blood count in Mn-treated rats

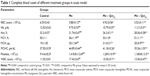

A complete blood count (CBC) is a blood test used to evaluate our overall health and detect a wide range of disorders. Abnormal increases or decreases in cell counts revealed in a CBC may indicate medical conditions that call for further evaluation. The effect of Qct on CBC – RBCs, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, platelets, and WBCs – in acute and subchronic Mn-treated rats are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Treatment with Mn significantly (P<0.001) altered CBC, while Mn + Qct groups significantly (P<0.01 or 0.001) reversed Mn-induced alterations in RBCs, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, platelets, and WBCs.

Effect of Qct on blood lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils in Mn-treated rats

Hematological properties of rats exposed to Mn in acute and subchronic groups are shown in Figures 3 and 4. Treatment with Mn significantly (P<0.01) increased neutrophil (Figures 3A and 4A) and eosinophil (Figures 3C and 4C) and decreased lymphocyte (Figures 3B and 4B) levels relative to the normal control group. However, the Mn + Qct groups showed significantly (P<0.01 or 0.001) decreased neutrophil (Figures 3A and 4A) and eosinophil (Figures 3C and 4C) and increased lymphocyte (Figures 3B and 4B) levels when compared to the Mn group.

Countereffect of Qct on blood macrophages and neutrophils in Mn-treated rats

Macrophages and neutrophils are involved in the activation of innate immunity, and represent hallmarks of toxicity. Our results showed that macrophages and neutrophils were more abundant in Mn-treated rats, while Qct treatment countered the effect in both the acute (Figure 5) and subchronic (Figure 6) models.

| Figure 5 Microscopic observations of the beneficial effect of Qct on blood macrophages and neutrophils in acute Mn-treated rat model. |

| Figure 6 Microscopic observation of the beneficial effect of Qct on blood macrophages and neutrophils in subchronic Mn-treated rat model. |

Beneficial effect of Qct against Mn-induced ER stress and ER stress-mediated apoptosis in acute and subchronic models

Western blot analyses were performed to investigate the effects of Mn and Qct on the expression of the ER-resident protein GRP78, transcription factor CHOP, and apoptotic hallmark protein caspase-3 in acute (Figure7) and subchronic (Figure 8) models. Our results revealed that Mn treatment significantly (P<0.001) increased expression of GRP78, CHOP, and caspase-3 proteins. However, Qct treatment significantly (P<0.01 or 0.001) reversed GRP78, CHOP, and caspase-3 activities.

Histopathological observation of Qct treatment in acute and subchronic models

In both acute (Figure 9) and subchronic (Figure 10) models, histopathological observation showed that there were no abnormal morphological changes in the liver, kidney, or lung tissues of the control rats, but the Mn group showed necrosis and tissue degeneration. However, the Mn + Qct groups protected tissues from Mn toxicity and maintained normal tissue architecture (Figures 9 and 10). In liver histopathology, the control group exhibited normal hepatic histological architecture, but the Mn group displayed morphological alteration of hepatic features, including aggregation of necrotic hepatocytes, inflammation, and necrosis, which were most prominent in the centrilobular region of the hepatic acinus. However, the Mn + Qct groups showed an improvement in hepatic alterations. In kidney histopathology, the control rats exhibited normal renal histological architecture, but the Mn group displayed morphological alteration of renal features, including necrosis in proximal and distal tubules, fragmentation or even disappearance of the brush border, disruption of cytoplasmic organelles, and glomerular injury. Moreover, the Mn + Qct groups showed protection against renal damage with mild–moderate recovery. In lung histopathology, the control group exhibited normal pulmonary architecture, but the Mn group displayed morphological alteration of pulmonary features, including moderate perivascular and peribronchiolar inflammation with granulomatous aggregation and mild neutrophil infiltration in the alveoli. Interestingly, the Mn + Qct groups showed an improvement in pulmonary damage with mild–moderate morphological change.

Immunohistochemical staining of 8-OHdG on Qct treatment in acute and subchronic models

8-OHdG is a common oxidative stress marker produced by oxidation of DNA bases. 8-OHdG immunoreactivity was significantly increased in rats treated with Mn compared to the control group. Moreover, immunoreactivity was significantly inhibited in groups treated with Qct in the acute and subchronic models (Figures 11 and 12).

Discussion

Acute and subchronic treatments with Mn induced significant alterations in organ-appearance, biochemical, hematological, and histopathology parameters. Significant progress has been made over the past decade regarding the mechanism by which Mn induces toxicity. Necrosis due to oxidative events has been implicated in provoking Mn-induced toxicity, with differences in mechanisms depending on signaling processes and disposition of Mn in different tissues.31–33 Studies have suggested a potent antioxidant capable of suppressing oxidative-initiated events within tissue.34,35 The protective effect of natural antioxidants, of which Qct is one, is remarkable on Mn toxicity. Recently, it was found that Qct exhibited beneficial effects in preclinical research against Mn toxicity.34

Several serum enzymes are used as indicators or markers for hepatocellular injuries, such as ALT and AST.36 Injured on liver release those cytosolic enzymes (ie, ALT and AST) in the blood cause elevation of their concentration in blood.37,38 From liver-function tests, we found that serum ALT and AST were significantly increased in rats treated with Mn. Interestingly, Qct treatment significantly reduced elevated ALT and AST levels in the acute and subchronic models (Figures 1 and 2).

The kidney is one of the most commonly affected organs after exposure to toxic metals.39 Creatinine, an indicator of kidney function, is increased during kidney failure or nephrotoxicity.40 Our results showed increased creatinine levels in the group treated with Mn, which may have been due to its nephrotoxic effect. Furthermore, Qct treatment significantly reduced creatinine levels in the acute and chronic models (Figures 3 and 4).

A CBC test measures several components and features of blood, gives information about the production of all BCs, and identifies the patient’s oxygen-carrying capacity through the evaluation of RBCs, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, platelets and WBCs.41 Our result showed that Qct treatment significantly reversed Mn-induced alteration of RBCs, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, platelets, and WBCs (Tables 1 and 2).41

We found a significant increase in the number of neutrophils and eosinophils and fewer lymphocytes after treatment with Mn in the acute and subchronic model rats (Figures 3 and 4). Increased neutrophils and eosinophils and fewer lymphocytes act as a causative factor in organ toxicity.42,43 Moreover, Qct treatment significantly attenuated Mn-induced alteration of hematological parameters. Our peripheral blood smears also showed that Mn treatment elevated the number of neutrophils and macrophages, while Qct treatment effectively counteracted this effect (Figures 5 and 6).44,45

We examined the effect of Qct on Mn-induced ER stress and ER stress-mediated apoptosis markers, including GRP78, CHOP, and caspase-3. ER-resident protein GRP78 regulates ER stress-signaling pathways, while CHOP and caspase-3 expression is most sensitive to ER stress and led to apoptosis.16,46,47 Our results demonstrated that GRP78, CHOP, and caspase-3 activities were increased with Mn treatment. However, Qct treatment effectively reversed Mn-induced GRP78, CHOP, and caspase-3 activities in acute and subchronic rat models (Figures 7 and 8).

With regard to the protective effect of Qct against Mn toxicity in acute and subchronic models, we observed histopathological features of liver, kidney, and lung tissue (Figures 9 and 10). We found that there were no abnormal histological changes in liver, kidney, or lung tissue of the control group, while the Mn group showed remarkable architectural changes in tissue.48,49 The Mn + Qct groups showed a protective effect against Mn toxicity and maintained the normal architecture of the tissues. Recently, it was reported that Qct decreases liver damage in mice with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, due to its known anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.50 Livers in the Mn group showed morphological alteration of hepatic features, especially zonal necrosis around the central vein, compared to the control group, while the Mn + Qct groups displayed protection of hepatic cells with mild–moderate necrotic changes.50 Liu et al suggested that Qct could protect rat kidney against lead-induced injury by improving renal function, attenuating histopathologic changes, reducing ROS production, renewing activities of antioxidant enzymes, and decreasing DNA oxidative damage and apoptosis.51 Kidneys in the Mn group showed histological alteration of renal features, especially glomerular injury, while the Mn + Qct groups exhibited an improvement in renal damage with mild–moderate recovery. Lungs of the Mn group exhibited morphological alteration of pulmonary features, especially granulomatous aggregation around bronchioles, while the Mn + Qct groups displayed protection of pulmonary damage with mild–moderate morphological change.

Oxidative stress is an important factor in the pathogenesis of any diseases, and 8-OHdG is a specific oxidative stress marker for DNA oxidation.52 Our previous study showed significant elevation in 8-OHdG in an Mn-treated group when compared to the control group.15 This elevation of 8-OHdG levels can be described by the formation of excessive ROS due to oxidative alteration of macromolecules and consequent genomic unsteadiness.50,53 In the present study, we found that 8-OHdG expression in the liver, kidney, and lung was elevated in Mn-exposed rats compared to normal control rats in acute and subchronic models. Interestingly, 8-OHdG expression was effectively counteracted in Mn + Qct group rats (Figures 11 and 12).48,51,54 It has been reported that Qct is a direct antioxidant and potent scavenger of ROS that decrease oxidation of DNA bases by modulation of antioxidant pathways.52–57 The present study suggests Qct could be a substantially promising organ-protective agent against toxic Mn effects and perhaps against other toxic metals, chemicals, or drugs.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that Qct effectively attenuated Mn-induced organ (liver, kidney, and lung) injury through regulation of biochemical and hematological parameters (ALT, AST, creatinine, and CBC), followed by reduction in oxidative damage, ER stress, and ER stress-mediated apoptosis (Figure 13). The present study suggests that Qct could be a substantially promising organ-protective agent against Mn toxic effects and perhaps against other toxic metals, chemicals, or drugs. However, additional studies are needed to determine the exact protective mechanism and long-term benefits of Qct on health.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Mr Raghupatil Junjappa and Hafiz Maher Ali Zeeshan, Department of Pharmacology, Medical School, Chonbuk National University, South Korea for their excellent technical assistance. This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2016R1A2B4015514).

Author contributions

This research was designed by EB and HOY. HJC and SYH provided conceptual and technical guidance for all aspects of the research. EB, GHL, HYL, HKK, and MH planned and performed in vivo rat experiments. Histopathological examination was performed by KRB and MKC. The manuscript was written by EB and HOY, and commented on by all authors. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Keen CL, Ensunsa JL, Watson MH, et al. Nutritional aspects of manganese from experimental studies. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20(2–3):213–223. | ||

Stephenson AP, Schneider JA, Nelson BC, et al. Manganese-induced oxidative DNA damage in neuronal SH-SY5Y cells: attenuation of thymine base lesions by glutathione and N-acetylcysteine. Toxicol Lett. 2013;218(3):299–307. | ||

Guilarte TR. Manganese and Parkinson’s disease: a critical review and new findings. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(8):1071–1080. | ||

Aschner M, Aschner JL. Manganese neurotoxicity: cellular effects and blood-brain barrier transport. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1991;15(3):333–340. | ||

Hudnell HK. Effects from environmental Mn exposures: a review of the evidence from non-occupational exposure studies. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20(2–3):379–397. | ||

Brurok H, Schjøtt J, Berg K, Karlsson JO, Jynge P. Manganese and the heart: acute cardiodepression and myocardial accumulation of manganese. Acta Physiol Scand. 1997;159(1):33–40. | ||

Schenkel-Brunner H, Cartron JP, Doinel C. Localization of blood-group A and I antigenic sites on inside-out and rightside-out human erythrocyte membrane vesicles. Immunology. 1979;36(1):33–36. | ||

Brurok H, Berg K, Sneen L, Grant D, Karlsson JO, Jynge P. Cardiac metal contents after infusions of manganese: an experimental evaluation in the isolated rat heart. Invest Radiol. 1999;34(7):470–476. | ||

Davis JM. Methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl: health risk uncertainties and research directions. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106(Suppl 1):191–201. | ||

Crossgrove J, Zheng W. Manganese toxicity upon overexposure. NMR Biomed. 2004;17(8):544–553. | ||

Han J, Lee JS, Choi D, et al. Manganese(II) induces chemical hypoxia by inhibiting HIF-prolyl hydroxylase: implication in manganese-induced pulmonary inflammation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;235(3):261–267. | ||

Roels H, Lauwerys R, Buchet JP, et al. Epidemiological survey among workers exposed to manganese: effects on lung, central nervous system, and some biological indices. Am J Ind Med. 1987;11(3):307–327. | ||

Yoon H, Kim DS, Lee GH, Kim KW, Kim HR, Chae HJ. Apoptosis induced by manganese on neuronal SK-N-MC cell line: endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and mitochondria dysfunction. Environ Health Toxicol. 2011;26:e2011017. | ||

Yoon H, Lee GH, Kim DS, Kim KW, Kim HR, Chae HJ. The effects of 3, 4 or 5 amino salicylic acids on manganese-induced neuronal death: ER stress and mitochondrial complexes. Toxicol In Vitro. 2011;25(7):1259–1268. | ||

Bahar E, Lee GH, Bhattarai KR, et al. Polyphenolic extract of Euphorbia supina attenuates manganese-induced neurotoxicity by enhancing antioxidant activity through regulation of ER stress and ER stress-mediated apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(2):E300. | ||

Bahar E, Kim H, Yoon H. ER stress-mediated signaling: action potential and Ca2+ as key players. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(9):E1558. | ||

Bahar E, Akter KM, Lee GH, et al. β-Cell protection and antidiabetic activities of Crassocephalum crepidioides (Asteraceae) Benth. S. Moore extract against alloxan-induced oxidative stress via regulation of apoptosis and reactive oxygen species (ROS). BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):179. | ||

Kawabata K, Kawai Y, Terao J. Suppressive effect of quercetin on acute stress-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response in Wistar rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;21(5):374–380. | ||

Eldahshan OA, Abdel-Daim MM. Phytochemical study, cytotoxic, analgesic, antipyretic and anti-inflammatory activities of Strychnos nux-vomica. Cytotechnology. 2015;67(5):831–844. | ||

Harwood M, Danielewska-Nikiel B, Borzelleca JF, Flamm GW, Williams GM, Lines TC. A critical review of the data related to the safety of quercetin and lack of evidence of in vivo toxicity, including lack of genotoxic/carcinogenic properties. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45(11):2179–2205. | ||

Formica JV, Regelson W. Review of the biology of quercetin and related bioflavonoids. Food Chem Toxicol. 1995;33(12):1061–1080. | ||

Li Y, Yao J, Han C, et al. Quercetin, inflammation and immunity. Nutrients. 2016;8(3):167. | ||

Wünsch B, Diekmann H, Höfner G. Stereoselective syntheses and CNS activity of novel tricyclic amines. Pharmazie. 1997;52(2):87–91. | ||

Mahesh T, Menon VP. Quercetin allievates [sic] oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Phytother Res. 2004;18(2):123–127. | ||

Liu CM, Sun YZ, Sun JM, Ma JQ, Cheng C. Protective role of quercetin against lead-induced inflammatory response in rat kidney through the ROS-mediated MAPKs and NF-kB pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820(10):1693–1703. | ||

Ansar S, Siddiqi NJ, Zargar S, Ganaie MA, Abudawood M. Hepatoprotective effect of quercetin supplementation against acrylamide-induced DNA damage in Wistar rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):327. | ||

Alam RT, Zeid EH, Imam TS. Protective role of quercetin against hematotoxic and immunotoxic effects of furan in rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2017;24(4):3780–3789. | ||

Camargo CA, da Silva ME, da Silva RA, Justo GZ, Gomes-Marcondes MC, Aoyama H. Inhibition of tumor growth by quercetin with increase of survival and prevention of cachexia in Walker 256 tumor-bearing rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;406(4):638–642. | ||

Su JF, Guo CJ, Wei JY, Yang JJ, Jiang YG, Li YF. Protection against hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats by oral pretreatment with quercetin. Biomed Environ Sci. 2003;16(1):1–8. | ||

Wang J, Zhang YY, Cheng J, Zhang JL, Li BS. Preventive and therapeutic effects of quercetin on experimental radiation induced lung injury in mice. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(7):2909–2914. | ||

Kitazawa M, Anantharam V, Yang Y, Hirata Y, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Activation of protein kinase Cδ by proteolytic cleavage contributes to manganese-induced apoptosis in dopaminergic cells: protective role of Bcl-2. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69(1):133–146. | ||

Latchoumycandane C, Anantharam V, Kitazawa M, Yang Y, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Protein kinase Cδ is a key downstream mediator of manganese-induced apoptosis in dopaminergic neuronal cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313(1):46–55. | ||

Roth JA. Homeostatic and toxic mechanisms regulating manganese uptake, retention, and elimination. Biol Res. 2006;39(1):45–57. | ||

Gawlik M, Gawlik MB, Smaga I, Filip M. Manganese neurotoxicity and protective effects of resveratrol and quercetin in preclinical research. Pharmacol Rep. 2017;69(2):322–330. | ||

Adedara IA, Subair TI, Ego VC, Oyediran O, Farombi EO. Chemoprotective role of quercetin in manganese-induced toxicity along the brain-pituitary-testicular axis in rats. Chem Biol Interact. 2017;263:88–98. | ||

Khoo ZY, Teh CC, Rao NK, Chin JH. Evaluation of the toxic effect of star fruit on serum biochemical parameters in rats. Pharmacogn Mag. 2010;6(22):120–124. | ||

Ramaiah SK. A toxicologist guide to the diagnostic interpretation of hepatic biochemical parameters. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45(9):1551–1557. | ||

Wiwi CA, Gupte M, Waxman DJ. Sexually dimorphic P450 gene expression in liver-specific hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α-deficient mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18(8):1975–1987. | ||

Tchounwou PB, Yedjou CG, Patlolla AK, Sutton DJ. Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. EXS. 2012;101:133–164. | ||

Yoshizumi WM, Tsourounis C. Effects of creatine supplementation on renal function. J Herb Pharmacother. 2004;4(1):1–7. | ||

George-Gay B, Parker K. Understanding the complete blood count with differential. J Perianesth Nurs. 2003;18(2):96–117. | ||

Xu R, Huang H, Zhang Z, Wang FS. The role of neutrophils in the development of liver diseases. Cell Mol Immunol. 2014;11(3):224–231. | ||

Fukuda T, Akutsu I, Nakajima K, et al. [The role of eosinophils, neutrophils and lymphocytes for the development of bronchial hyperresponsiveness in a guinea pig model of asthma]. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1990;28(10):1288–1293. Japanese. | ||

Sen Z, Jie M, Jingzhi Y, Dongjie W, Dongming Z, Xiaoguang C. Total coumarins from Hydrangea paniculata protect against cisplatin-induced acute kidney damage in mice by suppressing renal inflammation and apoptosis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:5350161. | ||

Kang KP, Kim DH, Jung YJ, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid attenuates cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury in mice by suppressing renal inflammation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(10):3012–3020. | ||

Wang M, Wey S, Zhang Y, Ye R, Lee AS. Role of the unfolded protein response regulator GRP78/BiP in development, cancer, and neurological disorders. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(9):2307–2316. | ||

Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107(7):881–891. | ||

Singh DP, Mani D. Protective effect of triphala rasayana against paracetamol-induced hepato-renal toxicity in mice. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2015;6(3):181–186. | ||

Otuechere CA, Abarikwu SO, Olateju VI, Animashaun AL, Kale OE. Protective effect of curcumin against the liver toxicity caused by propanil in rats. Int Sch Res Notices. 2014;2014:853697. | ||

Marcolin E, Forgiarini LF, Rodrigues G, et al. Quercetin decreases liver damage in mice with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;112(6):385–391. | ||

Liu CM, Ma JQ, Sun YZ. Quercetin protects the rat kidney against oxidative stress-mediated DNA damage and apoptosis induced by lead. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2010;30(3):264–271. | ||

Subash P, Gurumurthy P, Sarasabharathi A, Cherian KM. Urinary 8-OHdG: a marker of oxidative stress to DNA and total antioxidant status in essential hypertension with south Indian population. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2010;25(2):127–132. | ||

Azad N, Rojanasakul Y, Vallyathan V. Inflammation and lung cancer: roles of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2008;11(1):1–15. | ||

Abdou RH, Saleh SY, Khalil WF. Toxicological and biochemical studies on Schinus terebinthifolius concerning its curative and hepatoprotective effects against carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury. Pharmacogn Mag. 2015;11(Suppl 1):S93–S101. | ||

Boots AW, Haenen GR, Bast A. Health effects of quercetin: from antioxidant to nutraceutical. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;585(2–3):325–337. | ||

Costa LG, Garrick JM, Roquè PJ, Pellacani C. Mechanisms of neuroprotection by quercetin: counteracting oxidative stress and more. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:2986796. | ||

Calabrese V, Cornelius C, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Calabrese EJ, Mattson MP. Cellular stress responses, the hormesis paradigm, and vitagenes: novel targets for therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13(11):1763–1811. | ||

Ramesh N, Dangott B, Salama ME, Tasdizen T. Isolation and two-step classification of normal white blood cells in peripheral blood smears. J Pathol Inform. 2012;3:13. | ||

Nakada K, Fujisawa K, Horiuchi H, Furusawa S. Studies on morphology and cytochemistry in blood cells of ayu Plecoglossus altivelis altivelis. J Vet Med Sci. 2014;76(5):693–704. | ||

Woronzoff-Dashkoff KK. The Wright-Giemsa stain: secrets revealed. Clin Lab Med. 2002;22(1):15–23. | ||

Horobin RW, Walter KJ. Understanding Romanowsky staining – I: the Romanowsky-Giemsa effect in blood smears. Histochemistry. 1987;86(3):331–336. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.