Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 10

Hyponatremia after initiation and rechallenge with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole in an older adult

Authors Huntsberry A, Linnebur S , Vejar M

Received 13 February 2015

Accepted for publication 23 April 2015

Published 1 July 2015 Volume 2015:10 Pages 1091—1096

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S82823

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Walker

Ashley M Huntsberry,1 Sunny A Linnebur,1 Maria Vejar2

1University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Aurora, CO, USA; 2Division of Geriatrics, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to describe a case report of a patient experiencing hyponatremia from trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (TMP–SMX) upon initial use and subsequent rechallenge.

Summary: An 82-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with altered mental status thought to be due to complicated cystitis and was treated with TMP–SMX 160 mg/800 mg orally twice daily for 7 days. Her basic metabolic panel prior to initiation of TMP–SMX was within normal limits, with the exception of her serum sodium of 132 mmol/L (range 133–145 mmol/L). The day after completing her 7-day course of TMP–SMX therapy the patient was evaluated by her primary care provider and another basic metabolic panel revealed a reduction in the serum sodium to 121 mmol/L. The patient’s serum sodium concentrations increased to baseline 7 days after completion of the TMP–SMX therapy, and remained normal until she was treated in the emergency department several months later for another presumed urinary tract infection. She was again started on TMP–SMX therapy empirically, and within several days her serum sodium concentrations decreased from 138 mmol/L to a low of 129 mmol/L. The TMP–SMX therapy was discontinued upon negative urine culture results and her serum sodium increased to 134 mmol/L upon discharge. Based upon the Naranjo probability scale score of 9, TMP–SMX was the probable cause of the patient’s hyponatremia.

Conclusion: Our patient developed hyponatremia from TMP–SMX therapy upon initial use and rechallenge. Although hyponatremia appears to be rare with TMP–SMX therapy, providers should be aware of this potentially life-threatening adverse event.

Keywords: hyponatremia, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole combination, aged, drug-related side effects and adverse reactions

Introduction

Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (TMP–SMX) is a synthetic sulfonamide antibacterial combination product containing a ratio of 5:1 of sulfamethoxazole to trimethoprim. Sulfamethoxazole inhibits bacterial synthesis of dihydrofolic acid, while trimethoprim blocks the production of tetrahydrofolic acid through inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase.1–3 The synergism produces a bactericidal effect, which ultimately blocks the biosynthesis of proteins and nucleic acids required for bacterial survival. Common adverse reactions include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and diarrhea, as well as urticarial and allergic skin reactions.1 More serious side effects such as Stevens–Johnson Syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, aplastic anemia, agranulocytosis, and fulminant hepatic necrosis are rare but have been reported.1 There have been several reports of electrolyte abnormalities such as severe and symptomatic hyponatremia in patients receiving TMP–SMX, however, it is usually accompanied by hyperkalemia.4

Hyponatremia is a common electrolyte imbalance in which serum sodium concentrations fall below the normal range.5,6 Hyponatremia is particularly common among the elderly and hospitalized patients.7 Among the various risk factors for the occurrence of hyponatremia are medications such as selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors, thiazide diuretics, mirtazapine, and carbamazepine.6 The presence of hyponatremia upon admission or during hospitalization has been associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality.8 Severe hyponatremia can result in cerebral edema, seizures, coma, and eventually death. Too rapid of a correction of hyponatremia can lead to osmotic demyelination syndrome leading to irreversible neurological injury with significant morbidity and mortality.8 Although many cases of hyponatremia present asymptomatically, the implications if left untreated can be life-threatening.

Case report

An 82-year-old woman with a past medical history significant for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, rheumatoid arthritis, back pain, thyroid nodule, previous skin cancer, pancreatic insufficiency, and atrial fibrillation was prescribed TMP–SMX 160 mg/800 mg in the emergency department (ED) to treat a urinary tract infection.

Her drug allergies included clarithromycin (unknown reaction), cefuroxime (unknown reaction), ciprofloxacin (unknown reaction), gentamicin (unknown reaction), penicillin (unknown reaction), ceftriaxone (unknown reaction), vancomycin (unknown reaction), tramadol (caused a depressed and sedated state), morphine (unknown reaction), and IV contrast (unknown reaction). Her other medications prior to the ED visit included: acetaminophen 500 mg orally twice daily, allopurinol 100 mg orally daily, cholecalciferol 1,000 mg orally daily, digoxin 125 μg orally daily ×4 days and 62.5 μg daily ×3 days, docusate 100 mg orally twice daily, famotidine 20 mg orally twice daily, hydrocodone/acetaminophen 10–325 mg tablet orally every 6 hours as needed for pain, insulin glargine 12 units subcutaneously at bedtime, lipase–protease–amylase 15,000 units–51,000 units–82,000 units one capsule orally three times daily, lisinopril 5 mg orally twice daily, methotrexate 10 mg orally once weekly, metoprolol tartrate 50 mg orally twice daily, multivitamin orally once daily, nifedipine extended release 60 mg orally twice daily, prednisone 2 mg orally twice daily, sotalol 120 mg orally twice daily, warfarin 4 mg orally daily, folic acid 1.2 mg orally daily, hydralazine 25 mg orally three times a day, and Preservision Lutein capsule orally twice daily. The patient’s medications and dosages had been unchanged throughout the month prior except for a slight increase in her hydrocodone/acetaminophen, and she had not been taking any new supplements or over-the-counter medications. Her diet was poor due to lack of appetite, but this was unchanged. She weighed 46.6 kg, with a height of 61 inches, and her blood pressure and heart rate were 180/81 mmHg and 64 beats per minute, respectively.

The patient initially presented to the ED with altered mental status attributed to the presence of complicated cystitis and recent increase in her hydrocodone dose from 5/325 mg to 10/325 mg. She was admitted overnight, treated empirically with one dose of fosfomycin 3 g orally, and was then discharged on TMP–SMX for an additional 7-day course of therapy. Her initial urine culture was positive for beta hemolytic Group B Streptococcus, but sensitivities were not completed due to laboratory protocol. None of her other medications were changed during the brief hospitalization, other than patient education to stop her hydrocodone/acetaminophen 10/325 mg. During the hospitalization, the patient’s electrolytes, complete blood count, thyroid stimulating hormone, hepatic function panel, and lactate were evaluated and found to be normal, with the exception of a slightly low serum sodium of 132 mmol/L (reference range 133–145 mmol/L). Her sodium concentration 1 month prior was 134 mmol/L, indicating that her serum sodium concentrations were slightly low-normal at baseline.

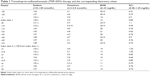

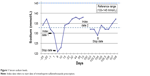

The patient presented to her primary care physician 1 day after completing her course of TMP–SMX. The patient was evaluated for depression and inability to sleep at night. She described some nausea, but denied any signs or symptoms of vomiting. A basic metabolic panel was ordered and the patient was given a prescription for mirtazapine 7.5 mg once daily at bedtime for sleep and depression. The same day, laboratory results from the office visit (Table 1) indicated a low sodium (121 mmol/L) and chloride concentration (92 mmol/L), an increased but normal potassium concentration (4.7 mmol/L), an increased but normal serum creatinine (1.1 mg/dL), and an increased blood urea nitrogen (24 mg/dL). A call was made to the patient to inform her that her sodium concentration was low and to not take the mirtazapine as it can further lower serum sodium. In addition, her lisinopril was held as her potassium had increased from 3.9 to 4.7 mmol/L since the hospitalization. At this point in time the patient had already taken one 7.5 mg tablet of mirtazapine and seemed to have tolerated it well, but she was instructed to hold further doses. The patient did not want to be admitted to the hospital despite the potential seriousness of her low sodium concentrations and was informed of the risks involved. She was instructed to increase her salt intake, but also increase her fluid intake due to her slightly dehydrated state. The patient came back to clinic 2 days later to make sure her sodium concentrations were increasing appropriately. Laboratory work revealed a sodium concentration slightly higher at 123 mmol/L. The patient was monitored closely, and her sodium concentrations increased to, and were maintained, in the normal range as of 8 days after stopping TMP–SMX (Table 1, Figure 1). At the visit where her sodium concentration normalized, the patient restarted mirtazapine and lisinopril, with no further anomalies in her sodium or potassium concentrations for the next 3 months. Her last serum sodium concentration during this time period was 138 mmol/L.

| Figure 1 Serum sodium levels. |

Several months later, with no further medication changes, the patient again presented to the ED for a possible urinary tract infection. She was empirically treated with TMP–SMX 160 mg/800 mg, but at an even higher dose of two tablets orally twice daily for 7 days. Three days after starting TMP–SMX, the patient was admitted to the hospital for a potential transient ischemic attack. Upon admission, her laboratory work revealed yet again a lower sodium concentration of 132 mmol/L. The next day her sodium concentration decreased even further to 129 mmol/L (Table 1, Figure 1), despite receiving intravenous fluids. Her urine culture results came back negative, so her TMP–SMX was discontinued. Starting with her admission day 1, the patient was given boluses and continuous intravenous infusions of sodium chloride 0.9% of 1,000–1,500 mL per day, and while not taking the TMP–SMX, her sodium concentrations increased to 134 mmol/L upon discharge.

All concurrent drugs in this patient were evaluated for the potential to cause hyponatremia and for drug–drug interactions with TMP–SMX. TMP–SMX was found to potentially interact with multiple drugs from the patient’s regimen (digoxin, methotrexate, insulin, sotalol, warfarin, and lisinopril), but none of the potential interactions were reported to contribute to hyponatremia. On its own, lisinopril has the ability to cause low serum sodium concentrations; however, the patient had been taking lisinopril for years with normal sodium concentrations. Mirtazapine can also cause significant sodium reduction; however, the patient first presented with low sodium prior to its initiation and she maintained normal serum sodium while taking mirtazapine in-between admissions. The patient’s diet and water intake had not fluctuated during the times of hyponatremia and were ruled out as causes. The TMP–SMX is the most likely cause for the patient’s hyponatremia, and based upon the Naranjo probability score of 9, it is highly probable.9

Discussion

The exact mechanism of TMP–SMX-induced hyponatremia is relatively unknown. It has been hypothesized that TMP–SMX blocks aldosterone-mediated sodium reabsorption in the collecting duct causing serum sodium concentrations to decline.10 Trimethoprim is also structurally related to potassium-sparing diuretics, which block sodium reabsorption at the distal nephron leading to potential hyponatremia and/or hyperkalemia.4,11 The most common electrolyte abnormality associated with TMP–SMX use is hyperkalemia, especially in those with kidney impairment or those taking concomitant drugs that can increase serum potassium concentrations (eg, lisinopril).1–4 A retrospective study of 53 patients was performed to identify whether similar electrolyte abnormalities occurred at low doses (TMP <80 mg) of TMP–SMX compared with standard doses (TMP 80–120 mg).4 Serum sodium, potassium, and creatinine concentrations were measured before and after taking TMP–SMX, and abnormalities were found in 14 of the 53 patients (either low sodium or high potassium). The doses were significantly higher in the patients with electrolyte disturbances (doses of 267.7±84.2 mg trimethoprim compared with 101.9±9.38 mg trimethoprim, P=0.0024). Electrolyte abnormalities were observed in 9.1% and 22.2% of patients taking a lower dose vs a higher dose, respectively. In total, 86% of patients with a serum creatinine of >1.2 mg/dL experienced electrolyte disorders, compared with only 17.5% with normal renal function. Overall, even though electrolyte disturbances were seen more frequently with high-dose TMP–SMX, low doses were found to cause both hyperkalemia and hyponatremia, particularly in those with underlying kidney dysfunction. No analysis was done based upon age.

Several reports have indicated that there is a pronounced correlation between the use of TMP–SMX and hyponatremia in patients with Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia.2,11,12 In one case, a 28-year-old man with HIV and P. jiroveci was treated with TMP–SMX and his serum sodium concentrations decreased from a baseline of 135 mmol/L to 117 mmol/L after 7 days of TMP–SMX therapy.11 Upon both discontinuation of TMP–SMX and supplementation with sodium chloride, his serum sodium concentrations stabilized in the 126–129 mmol/L range, and eventually were maintained at his baseline concentration. In another case report, a 42-year-old man with HIV was treated with high-dose TMP–SMX (20 mg/kg) for Pneumocystis carinii.12 After 4 days of TMP–SMX therapy, his serum sodium concentrations decreased from 137 mmol/L at baseline to 121 mmol/L. Upon discontinuation of TMP–SMX, treatment with pentamidine and demeclocycline, as well as water restriction, his serum sodium increased to 139 mmol/L within several days.12 Despite the familiarity of hyponatremia associated with the use of TMP–SMX in immunocompromised patients, the effect in the immunocompetent patient is less clear. Events of hyponatremia are mentioned briefly in the 2013 update to TMP–SMX product labeling regarding the increased incidence of hyponatremia particularly in those being treated for P. jiroveci pneumonia, but the update failed to give more detailed information regarding the risk in other populations.2

In another reported case, trimethoprim monotherapy with a concurrent diuretic was found to be associated with the development of hyponatremia.13 A 75-year-old woman with recurrent urinary tract infections and a baseline serum sodium concentration of 136 mmol/L was placed on trimethoprim 200 mg orally twice daily. At the time, the patient was also taking amiloride 10 mg/hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) 100 mg two tablets orally daily. Four days after starting trimethoprim treatment, she became symptomatically hyponatremic with a serum sodium of 107 mmol/L. The patient was abruptly taken off both trimethoprim and amiloride/HCTZ therapy and her serum sodium concentrations gradually rose to 135 mmol/L over the next 11 days. She was placed back on amiloride/HCTZ and maintained normal serum sodium concentrations over the next 4 months. Upon rechallenge with trimethoprim 200 mg orally twice daily, without concurrent amiloride/HCTZ, her serum sodium concentrations did not fall. However, once the amiloride/HCTZ was reintroduced with the trimethoprim, her serum sodium fell to the 120–125 mmol/L range within several days. Five weeks after discontinuation of trimethoprim, her serum sodium was 141 mmol/L.13 Trimethoprim therapy, without sulfamethoxazole, seemed to be the cause of the patient’s hyponatremia, however, only in combination with another drug such as amiloride/HCTZ. The combination of the two drugs were hypothesized to have a dual effect on renal tubular secretion and sodium handling, particularly in the older adult patient who was already at risk for kidney impairment and hyponatremia.13

TMP–SMX may also have another synergistic effect with citalopram as evidenced by the case report of a 79-year-old woman with a baseline serum sodium of 140 mmol/L admitted with a serum sodium of 119 mmol/L.14 Citalopram had recently been initiated 7 days prior to her hospital stay, along with TMP–SMX 3 days prior. Upon admission, both of these medications were discontinued and she received a slow infusion of 3% NaCl, which increased her serum sodium to 129 mmol/L. Over the course of the next 4 days she was placed on fluid restriction and her serum sodium increased to 136 mmol/L.14 It was hypothesized that a synergistic mechanism between citalopram and TMP–SMX caused a rapid and severe hyponatremic event in this patient. Given the patent’s rapid improvement upon day 4, the reversal of her hyponatremia was attributed to the discontinuation of TMP–SMX given the rather long half-life of citalopram. The authors suggested that providers use caution when adding TMP–SMX therapy to other hyponatremic-inducing drugs such as selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors, particularly in the elderly population or those with renal dysfunction.14

We found only one case report with a similar presentation to that of our patient. An 86-year-old man developed hyponatremia, independent of hyperkalemia, while taking TMP–SMX 80 mg/400 mg one tablet orally twice daily for a possible urinary tract infection.15 Four days after starting the TMP–SMX therapy, he presented to the ED with altered mental status, weakness, and fatigue. Upon further investigation, his serum sodium concentration at the time of admission was 127 mmol/L (baseline serum sodium of 138 mmol/L). After discontinuing TMP–SMX and HCTZ, his sodium concentrations returned to 133 mmol/L on day 8 of his hospital stay. He was discharged from the hospital on day 9 and HCTZ was not reinitiated. It was later discovered that approximately 6 months prior he also took TMP–SMX 160 mg/800 mg for a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus soft-tissue infection and was admitted to the hospital for altered mental status and a serum sodium concentration of 128 mmol/L. TMP–SMX was discontinued and his serum sodium concentration increased with fluid restriction.

In this case and in our patient, hyponatremia occurred within days of initiating TMP–SMX and was independent of hyperkalemia. The time course over which the hyponatremic events took place in both patients was similar, and the resulting increase in serum sodium concentrations was observed within days of discontinuation of TMP–SMX. Both patients were elderly, and possibly predisposed to an increased risk of hyponatremic events based upon age alone. Although our patient had 1 day with an elevated potassium concentration, it did not reoccur on later days.

Conclusion

Our patient case, along with the above studies and other cases, supports the theory that TMP–SMX may cause hyponatremia in addition to hyperkalemia. Based upon the Naranjo adverse drug reaction probability scale (9 out of 13), TMP–SMX is the probable cause of our patient’s hyponatremic events.9 The patient’s hyponatremia occurred after TMP–SMX initiation and dissipated upon discontinuation. The patient was then rechallenged several months after the initial event and hyponatremia reoccurred. Dietary concerns were ruled out and other possible drug causes from the patient’s regimen were also ruled out as causes.

Our patient case emphasizes the need for careful consideration of antimicrobial agents in older adults. For a patient with acute cystitis with a predisposition to hyponatremia, antimicrobial option may include TMP–SMX, nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin, pivmecillinam, fluoroquinolones, and some beta-lactams. Depending on the patient’s culture and sensitivity results, these agents may be appropriate and most of them will not likely contribute to hyponatremia. Similar to TMP–SMX, ciprofloxacin has been reported to cause serious hyponatremia. In contrast, levofloxacin has not and fosfomycin has been associated with hypernatremia following parenteral administration.

If TMP–SMX is deemed to be the most appropriate antimicrobial agent for the patient, then monitoring of electrolyte disturbances, particularly serum sodium, in the elderly and those with underlying kidney dysfunction, prior to initiation and throughout therapy with TMP–SMX, may help prevent potentially life-threatening hyponatremia. Further research in this area would be helpful.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim [package insert]. Philadelphia: Mutual Pharmaceutical Company, Inc; 2005. | ||

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim [product information]. Philadelphia, PA: AR Scientific, Inc.; 2013. | ||

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. In: Micromedex Drugdex [online database]. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics. Accessed September 14, 2014. | ||

Mori H, Kuroda Y, Imamura S, et al. Hyponatremia and/or hyperkalemia in patients treated with the standard dose of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Intern Med. 2003;42:665–669. | ||

Reynolds RM, Padfield PL, Seckl JR. Disorders of sodium balance. BMJ.2006;332:702–705. | ||

Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hyponatremia: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med.2013;126(10 Suppl 1):S1–S42. | ||

Rosenblatt DE, Opdycke RA, Kustryzk BM, et al. Incidence of hyponatremia in elderly patients on hospital admission. J Geriatr Drug Ther. 1996;11:71–84. | ||

Wald R, Jaber BL, Price LL, et al. Impact of hospital-associated hyponatremia on selected outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170: 294–302. | ||

Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30: 239–245. | ||

Kaufman AM, Hellman G, Abramson RG. Renal salt wasting and metabolic acidosis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy. Mt SinaiJ Med. 1983;50:238–239. | ||

Ahn YH, Goldman JM. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and hyponatremia. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:161–162. | ||

Babayev R, Terner S, Chandra S, et al. Trimethoprim-associated hyponatremia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:1188–1192. | ||

Eastel R, Edmonds CJ. Hyponatremia associated with trimethoprim and a diuretic. BMJ. 1984;289:1658–1659. | ||

Redding JM, Nichols S, Hallen S. Rapid onset hyponatremia after initiating TMP/SMX and citalopram. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(Suppl 4):S189–S190. | ||

Dunn RL, Smith WJ, Stratton MA. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-induced hyponatremia. Consult Pharm. 2011;26:342–349. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.