Back to Journals » Drug Design, Development and Therapy » Volume 13

Escin: a review of its anti-edematous, anti-inflammatory, and venotonic properties

Authors Gallelli L

Received 5 March 2019

Accepted for publication 9 July 2019

Published 27 September 2019 Volume 2019:13 Pages 3425—3437

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S207720

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Qiongyu Guo

Luca Gallelli1,2

1Department of Health Science, School of Medicine, University of Catanzaro, Catanzaro, Italy; 2Operative Unit of Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacovigilance, Azienda Ospedaliera Mater Domini, Catanzaro, Italy

Correspondence: Luca Gallelli

Operative Unit of Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacovigilance, Azienda Ospedaliera Mater Domini, Viale Tommaso Campanella 115, Catanzaro 88100, Italy

Tel +39 96 171 2322

Fax +39 96 177 4424

Email [email protected]

Abstract: This review discusses historical and recent pharmacological and clinical data on the anti-edematous, anti-inflammatory, and venotonic properties of escin (Reparil®). Escin, the active component of Aesculus hippocastanum, or horse chestnut, is available as orally absorbable dragées and as a transdermal gel. The anti-inflammatory and anti-edematous effects of escin have been studied over many years in pre-clinical models. More recent data confirm the anti-inflammatory properties of escin in reducing vascular permeability in inflamed tissues, thereby inhibiting edema formation. The venotonic effects of escin have been demonstrated primarily by in vitro studies of isolated human saphenous veins. The ability of escin to prevent hypoxia-induced disruption to the normal expression and distribution of platelet endothelial cell-adhesion molecule-1 may help explain its protective effect on blood vessel permeability. Escin oral dragées and transdermal gel have both demonstrated efficacy in blunt trauma injuries and in chronic venous insufficiency. Both oral escin and the transdermal gel are well tolerated.

Keywords: blunt trauma, chronic venous insufficiency, edema, escin, pain, Reparil®

Introduction

Local soft tissue edema is one of the main common symptoms of acute conditions, such as post-traumatic or post-surgical events, or chronic conditions like chronic venous insufficiency (CVI).1 CVI itself is a result of macrovascular and microvascular changes in the lower extremities, including basement membrane thickening, capillary bed malformation (enabling increased fluid permeability), and endothelial damage.1

The role of the endothelium in transvascular exchange has long been studied.2 In cases of local inflammation, hypoxic damage to endothelial cells augments the local inflammatory process, and ultimately leads to impairment of endothelial functions.3,4 Immunohistochemical studies have shown that hypoxic conditions reduce the expression of cytoskeletal proteins and platelet endothelial cell-adhesion molecule (PECAM), which are important for maintenance of the intercellular junction proteins, and promote the release of pro-inflammatory molecules such as vascular cell-adhesion molecule (VCAM-1).4

CVI and post-traumatic soft tissue damage are therefore both characterized by hypoxic vulnerability of capillary vessels, and any treatment for CVI or edema should aim to restore normal oxygen levels (normoxia). The mainstay of treatment for CVI is compressive stockings,1,5 with surgical and/or pharmacologic therapies also prescribed depending on severity.1 However, a concomitant medication aimed at protecting endothelial cells from hypoxic damage would be also beneficial, to reduce the loss of capillary function.

Escin is the active component of Aesculus hippocastanum, the horse chestnut, which was itself used as a traditional medicine for centuries,6 and is still used to treat certain conditions, including hemorrhoids,7 varicose veins, hematoma, and venous congestion.8 Escin was first isolated in 1953,6 and has demonstrated anti-edematous, anti-inflammatory, and venotonic properties in various preparations.9 It has also shown effectiveness as an adjunct10 or alternative11 to compression therapy, and is known to act directly on endothelial hypoxia.9

This review describes the chemical properties and pharmacology of escin, as well as the pharmacokinetics and clinical uses of escin oral dragée and gel formulations (Reparil®, Meda Pharma SpA, Milan, Italy – a Mylan Company).

Methods

The review was based on articles identified via an initial search of PubMed using the terms escin AND ((chronic venous insufficiency) OR (injury)), not restricted by date or language. The resulting articles were assessed by the author for suitability for this review. For data on pharmacokinetics and clinical use, only studies involving Reparil® formulations are included in this report. Articles on escin preparations not based on Aesculus hippocastanum semen were excluded.

Chemistry

In the 1960s, Lorenz et al found that horse chestnut seeds contain a fraction consisting of a mixture of the triterpenic sapogenins, which could be chemically isolated without denaturation.12 These pentacyclic triterpenic sapogenins were identified as protoescigenin and barringtogenol, and the fraction was named escin (and later β-escin).13

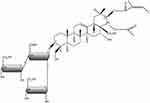

Escin includes a trisaccharide linked to the 3-OH residue (glucose, xylose, and galactose), and the C21 and C22 domains are esterified with an organic acid (e.g., angelic, tiglinic, or acetic acid).8 The main escin isomers are β-escin (the basis of the pharmaceutical preparations of the formulations of escin in this review) and kryptoescin. β-escin is relatively water-insoluble while kryptoescin is readily water-soluble, but considerably less active than β-escin.8 The molecular formula of escin is C55H86O24, and its molecular weight is 1131.27 Da (Figure 1).8 The mode of action of escin is shown in Figure 2,9 and is further described in the “Pharmacology” section.

|

Figure 1 The chemical structure of the key saponin in escin. |

|

Figure 2 The mode of action of escin. |

Preparations

Raw escin 2.5% is extracted with methanol and water from a purified, concentrated, homogenized preparation of horse chestnut seeds. It is subsequently further purified and crystallized as pure escin.8

Dragées with orally absorbable escin

The low water solubility of crystallized escin (<0.01%) means its bioavailability after oral administration is low.14 However, the development of a specific production technology has enabled the modification of crystalline escin, rendering it more water-soluble and, therefore, suitable for oral administration.15

Comparative technical and biological analyses showed that this modification of the crystalline structure of escin into an amorphous state increased its water solubility by approximately 2%,16 meaning it could be used as the active principle ingredient of gastroresistant dragées, the first oral form of absorbable escin (at doses of 20 and 40 mg).

Escin gel for transdermal application

The escin-based gel formulation for transdermal application is a pharmaceutical preparation combining 1% or 2% escin and 5% diethylaminosalicylate (DEAS) in an isopropylalcohol gel formula. The clinical indications for the escin-based gel formulation are treatment of localized edema, blunt lesions, hematoma, superficial thrombophlebitis, and vertebral painful syndrome.

Pharmacology

At least three types of pharmacological action of escin have been identified: 1) anti-edematous and anti-inflammatory effects; 2) effect on venous tone; and 3) protection of hypoxic damage to the endothelium.

Anti-edematous and anti-inflammatory effects

The inflammatory process may be described as a cascade, beginning with a decrease in ATP content in endothelium cells, for example, as in blood stasis in CVI.3 In turn, this results in increased cellular calcium concentrations and the release of inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandins17 and platelet-activating factor.18 This leads to the recruitment, activation, and adhesion of polymorphonuclear neutrophils.3 In the course of an inflammatory reaction, histamine and serotonin, which increase capillary permeability, are also released. The net result of these changes is extravascular migration of leukocytes, exacerbation of inflammation, edema, and pathological venous changes.19

The effects of escin on inflammation and edema have been confirmed in various preclinical models over many years. In a study in 1961, intravenous (IV) administration of escin 0.2 and 2.5 mg/kg was found to significantly reduce acute edema induced in a rat paw model, and in the same study, escin was found to inhibit the increase in vascular permeability induced by egg white injection.20 Hampel et al investigated the anti-inflammatory effects of escin in an animal model, in which local inflammation was induced in the abdominal skin surface of rabbits using chloroform. Escin, at doses of 0.5–2 mg/kg for IV administration and 10–40 mg/kg for oral administration, dose-dependently reduced capillary permeability.21 In a further experiment in rabbits, IV escin 0.3 and 1.0 mg/kg was associated with dose-dependent antagonism of bradykinin-induced increases in capillary permeability, with a resultant decrease in lymph fluid exudation.22 In a rat model of pleurisy, IV escin 0.35, 0.5, and 0.7 mg/kg reduced exudate in a dose-dependent manner.23

The mechanism underlying the anti-edematous and anti-inflammatory effects of escin are not clear, but they may involve a number of actions. In vitro experiments demonstrated that incubation with escin strongly inhibited the activity of hyaluronidase, which degrades hyaluronic acid, the main component of the capillary extravascular matrix.24 Recovery of components such as hyaluronic acid may reduce leakage of plasma from endothelium and may help to explain the effect of escin on edema. A recent study showed that the anti-inflammatory effects of escin gel may be mediated by an effect on the glucocorticoid receptor (GR).25 In the skin from rat models of paw edema and capillary permeability, escin gel treatment at doses of 0.02 and 0.04 g/kg increased GR levels to a similar degree in both models. Further analysis in both models demonstrated increased expression of NF-κB, P38MAPK mRNA, and increased expression of protein NF-κB, P38MAPK, and AP-1. Treatment with escin (0.02 and 0.04 g/kg) significantly inhibited the expressions of NF-κB and AP-1 and the mRNA expression of NF-κB (p<0.05).25 Co-administration of suboptimal concentrations of IV escin and corticosteroids inhibited the secretion of nitric oxide, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-1β in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophage cells, and these changes were associated with a marked reduction in exudate in a model of pleuritis and reduced edema volume in a rat paw model.26 Treatment with suboptimal concentrations of escin or corticosteroids alone did not induce these changes, suggesting synergistic anti-inflammatory effects.26 In mice, escin 0.45, 0.9, or 1.8 mg/kg given intragastrically protected against indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers, and caused significant reductions in the malondialdehyde, TNF-α, P-selectin, and VCAM-1 content in gastric tissue.27 In the same experiment, intragastric escin also reduced myeloperoxidase activity, as well as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, indicating an antioxidant effect.27

These results indicate that, due to inhibition of the release of inflammatory inhibitors, escin has specific anti-inflammatory properties in reducing vascular permeability in inflamed tissues, thereby inhibiting edema formation, as well as potential anti-oxidative effects.

Effect on venous tone

The effects of horse chestnut extracts and escin on venous tone have been primarily demonstrated in isolated human saphenous veins, specifically by in vitro studies of normal venous segments obtained during surgical saphenectomy procedures.8

Escin stimulation of human saphenous vein segments pretreated with norepinephrine consistently induced an increase in venous tone, which was maintained for up to 1 hr after escin had been washed from the vein.28 The increase in venous tone obtained with escin 5–10 µg/mL was abolished following incubation with indomethacin (1 µg/mL) and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, indicating a prostaglandin (PG)F2α-dependent effect of escin on venous tissue.29 In a separate experiment, escin 1–100 mg/mL led to effective contraction of venous tissue from ankle and groin areas, but did not improve tone in venous segments from the more severely tortuous saphenous vein,30 suggesting that the effects of escin may be maximal when used early in the course of CVI.

Prevention of hypoxic damage to the endothelium

The hypothesis that escin inhibits the deleterious cellular cascade induced by hypoxia, and the mechanisms by which this occurs, has been tested in various in vitro and ex vivo models.

In an in vitro experimental model of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) incubated under hypoxic conditions, ATP was reduced by 40% and the activity of phospholipase A2 (PLA2), an enzyme responsible for the release of precursors of inflammatory mediators, was increased 1.9-fold (Figure 3A).3 Escin, at concentrations of 100–750 ng/mL, partially protected against the loss of ATP, and inhibited hypoxia-induced increases in PLA2 by 57–72%.3 The same study showed that hypoxia-activated endothelial cells also have increased adhesiveness for neutrophils, and that this process can be prevented dose-dependently by escin (Figure 3B).3 In another study, HUVECs were exposed to conditions mimicking hypoxia (induced by exposure to cobalt chloride [CoCl2] and inflammation induced by exposure to Escherichia coli LPS), to further detail the mechanism of action of escin on the vascular endothelium.4 PECAM-1, VCAM-1, and IL-6 were chosen as molecular targets, because they are markers of alteration of endothelial barrier function and leukocyte adhesion. In particular, PECAM-1 is critical to the maintenance of adherent junction integrity at inter-endothelial cell-adhesion sites, and appears to convert mechanical forces such as shear stress into chemical signals. PECAM-1 is a key regulator of neutrophil transmigration through the basement membrane in inflammation, ischemia-reperfusion, and oxidative injury.4 As shown in Figure 4A, hypoxia was associated with disruption of the normal expression and distribution of PECAM-1, whereas escin prevented the resulting damage.4 This may explain why escin prevents pathological increases in blood vessel permeability. Hypoxia also led to reorganization of the endothelial cytoskeleton, while escin showed prevention of this cytoskeletal disruption (Figure 4B and C).

|

Figure 3 Effect of escin on (A) phospholipase A2 and (B) neutrophil adherence in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Adapted with permission from Arnould T, Janssens D, Michiels C, Remacle J. Effect of aescine on hypoxia-induced activation of human endothelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;315(2):227–233.3 Copyright © 1996 Published by Elsevier B.V. |

When just-isolated umbilical veins have been studied under hypoxic conditions, hypoxia has been shown to elicit an increase in neutrophil adhesiveness.31 After these umbilical vein segments were incubated for 2–6 hrs with escin at concentrations of 100–750 μg/mL, hypoxia-induced damage was reduced compared with the control groups.31 In this study, the hypoxia-induced formation of superoxide anions and leukotriene B4 was almost completely prevented by escin.31

The role of the endothelium in venous insufficiency and a potential link with arterial endothelial dysfunction led to an experiment conducted in rat aortic rings, in which escin prevented pyrogallol-induced reduction in acetylcholine relaxation, thus demonstrating a potential to promote endothelial function.32

An in vitro study by Domanski et al found that β-escin was associated with the protection of the endothelial layer against TNF-α-induced permeability, significantly increased total cellular cholesterol content, and reduced TNF-α-induced NFκB activation, thus providing further possible explanations for the effects of escin on endothelial function.33

In HUVECs or ECV304 cells, β-escin sodium (10, 20, or 40 μg/mL) dose-dependently inhibited endothelial cell proliferation, and at 40 μg/mL also induced apoptosis of endothelial cells.34

Pharmacokinetics

Oral administration

In animal models, 13–16% of an oral dose administered by gastric probe is absorbed (non-volatile radioactivity), with a maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) achieved about 4 hrs after the administration, and about two-thirds is subsequently excreted via bile.35 In rats, the absorption of escin Ib and isoescin were evaluated after IV or oral administration. Low oral bioavailability (F) values of 2% were observed for both compounds, and the administration of sodium escinate, which contains the two isomers, resulted in higher terminal phase half-life (t1/2) and mean residence time values for both escin Ib and isoescin Ib compared to administration of either isomer alone.36

Topical application

In transcutaneous absorption studies, 3H-escin was applied on dorsal and ventral skin in mice, rats, guinea pigs, and pigs, and total radioactivity, non-volatile radioactivity, and thin-layer chromatography were assessed at different time points in several tissues and organs.37 In mice and rats, 25% and 50%, respectively, of the radiolabelled topical dose was absorbed by the skin. Overall, 1% of the dose of escin was excreted, with one-third each being unaltered escin, non-volatile metabolites, and volatile radioactivity.37 In mice, only one-third to one-quarter of non-volatile radioactivity measured in blood was related to native escin, and in rats only one-sixth to one-seventh of the absorbed dose was excreted as unmodified escin.37 Following topical administration in pigs, high escin concentrations were found under the site of application, even in deeper muscle structures, but in only low amounts in the internal organs, blood, and dorsal musculature, with total excretion in bile and urine estimated at 1–2.5%.38

Drug–drug interactions

Studies have indicated that herbal products containing coumarin derivatives, such as the Aesculus hippocastanum, may potentiate the anticoagulant activity of warfarin by increasing the international normalized ratio.39 However, these coumarin derivatives (aesculin and fraxetin) are present in the bark of Aesculus hippocastanum,40 but not in the seeds or the seed shell, which is the part of the plant from which the active component of escin is derived.8

Clinical use

Oral administration

Trauma

The clinical efficacy of oral escin in inhibiting edema formation has been demonstrated in a number of trials in orthopedic patients.41,42

gIn a double-blind, parallel-group, 3-arm, clinical study, 300 patients with postoperative or post-traumatic soft tissue swelling (contusion, sprain, or fracture traumas) were treated for 14 days with oral escin (20 mg three times a day), placebo, or a fibrinolytic control drug (serratiopeptidase 5 mg three times a day).42 There was a reduction in edema (slight improvement or better) in 82.3% of patients in the oral escin group compared with 75% in the fibrinolytic control group and 72.4% in the placebo group (p<0.05 for escin vs placebo by day 3). Escin also scored significantly better in subjective evaluation criteria at the end of the 14-day treatment.42 The number of adverse events in the three groups was 4 (4.1%), 7 (7.1%), and 8 (8.1%), respectively.

A placebo-controlled, parallel-group, 4-arm study was conducted in 100 orthopedic patients (50 with post-plastering edema and 50 with reactive post-traumatic edema).41 In each group, 40 patients received oral escin (2×20 mg three times a day) and 10 were treated with placebo. Limb circumference, plethysmography, and the presence or absence of spontaneous pain were evaluated. In this study, treatment with escin improved post-plastering edema in 92% of patients and post-traumatic edema in 95% of patients, with the majority of the improvement occurring in the first 3 weeks of treatment.41 The mean difference in water volume change after 4 weeks of treatment was –680 mL post-plaster and −1090 mL post-trauma with escin, and –230 mL post-plaster and –330 mL post-trauma with placebo (Figure 5A and B).41

|

Figure 5 Reduction of (A) post-plastering or (B) post-surgical edema after treatment with oral escin or placebo (statistical analyses not available). Adapted from unpublished data from MedaPharma SpA.41 |

Venous insufficiency

The efficacy of oral escin administration in patients with CVI was evaluated in a double-blind, randomized, clinical study in 80 patients with stage 2 and 3 saphenous vein varices.43 In this study, patients received oral escin 2×20 mg three times a day (n=40) or placebo (n=40) for 21 days, and improvement in circulation was measured using light reflection rheography (LRR) to record venous filling status and venous refilling time; pain, swelling and stretching sensation were also measured. On day 14, the refilling time in the escin-treated group had increased from 13 to 31 s (a 168% increase), while no significant difference was observed in the placebo group. At the end of the study, a significantly greater increase in refilling time was still observed in the escin group compared with the placebo group (p<0.0001 between groups). There was a substantial improvement in symptomatic criteria after 14 days of treatment with escin, whereas no significant change occurred in the placebo-treated group.43

The effect of oral escin 2×20 mg three times a day has also been compared with that of placebo in a study of 195 women with various venous disorders of the pelvis or legs, including varicose veins; both groups were treated for 25 consecutive days, followed by 5 days without treatment, for≥3 months.44 Efficacy was evaluated on the basis of an observer-blind assessment of symptom improvement, classified as “very good”, “good”, “moderate”, or “bad”. In the escin-treated group, there was an 85% increase in the scores for “very good” and “good”, in contrast with a 12% increase in the placebo-treated group.44

Topical administration

Trauma

Sports injuries constitute 10–19% of all acute injuries treated in the emergency room.45 Typical sports injuries are characterized by contusion, strain, stretching, and crushing, with or without consequent hematoma formation. Injury results in vasoconstriction, with release of serotonin and thromboxane A2, and release of prostacyclin by cell membranes, in order to prevent blood leakage. Platelets adhere to damaged blood vessels, initiating hemostasis. The inflammatory response prompts vasodilation, which is stimulated by nitric oxide, bradykinin, histamine, and prostaglandins. The increase in vascular permeability allows neutrophils to interact with the endothelium, while selectin mediates the capture and recruitment of leukocytes along the surface of endothelial cells, followed by the actions of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 molecules to allow leukocyte adhesion to the endothelium.46 Clinically this presents as swelling and pain, functional limitation, and reduced mobility.

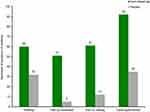

To investigate the effect of escin-based gel on limb contusion trauma and mobility, 100 patients with blunt sport lesions were randomized to receive topical 2% escin+5% DEAS gel (mean daily dose 5 applications; n=50) or matching placebo (mean daily dose 4 applications; n=50) in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study.47 In the escin group, the mobility of the injured limb increased from 50% to 89% compared with the uninjured limb within 9 days (p<0.02), versus a smaller increase in mobility from 50% to 67% in the placebo group. No changes were found in the circumference measurements on the lower limbs of patients in the placebo group, while the circumference of the injured leg in the escin group had almost returned to that of the uninjured leg within the mean treatment period of 9 days (p<0.02). In general, patients evaluated escin-based gel performance as “very good” or “good”; in contrast, the evaluation of the placebo treatment was mainly “moderate” or “ineffective”.47 In the same study, a significantly greater proportion of patients in the escin group than in the placebo group had remission of swelling, pain on movement, pain on loading, and local hyperthermia (Figure 6).47

|

Figure 6 Remission of symptoms following blunt trauma after treatment with escin-based gel or placebo (all p<0.05 for escin-based gel vs placebo). Data from Rothhaar and Thiel.47 |

Another randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical study compared the efficacy of 2% escin+5% DEAS gel with that of a gel containing 1.16% diclofenac diethylamine salt in 140 volunteers with experimentally induced sub-injection hematoma.48 The main efficacy outcome was the area under the curve (AUC) of pressure until pain was experienced. The AUC for pain threshold was higher in the escin combination group versus the diclofenac group (38.68 vs 30.71 h∙kp/cm2; p<0.0004). Furthermore, pain on pressure was restored to the normal threshold (value before induction of the hematoma) significantly more rapidly with the escin combination gel than with the diclofenac gel (p<0.001).48

In a double-blind study published in 2001, 126 patients with blunt injuries of the extremities were randomized to treatment with one of the following gels: 1% escin+5% DEAS (n=32), 1% escin+1% sulfated escin with heparinoid properties (PSNA)+5% DEAS (n=31); 2% escin+5% DEAS (n=32); or placebo (n=31).49 The primary efficacy variable was mean AUC for tenderness. Mean AUC for tenderness over 6 hrs after treatment was significantly lower with all escin-containing gels than with placebo (1099.06, 1170.74, 1177.93, and 734.02 kp∙min/cm2 in the 1% escin, 1% escin+1% PSNA, 2% escin, and placebo groups, respectively; p=0.0001 for all active-treatment groups vs placebo), with no statistically significant differences between the three active-treatment groups.49

More recently, the clinical efficacy of escin-containing gels in the topical treatment of blunt impact injuries was investigated in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study.50 A total of 158 participants in soccer, handball, or karate competitions were enrolled within 2 hrs of sustaining a strain, sprain, or contusion, and randomized to topical administration of one of the following, three times over 8 hrs: 1% escin-based gel; 2% escin-based gel (both gels contained 5% DEAS); or placebo. The primary efficacy variable was AUC for tenderness over a 6-hr period, where tenderness was measured by applying pressure to the center of the injury using a calibrated caliper, with a higher AUC indicating lower pain sensitivity, and a better clinical response. The two gel preparations containing 1% and 2% escin were significantly more effective than placebo, with both showing a higher mean AUC over 6 hrs versus placebo (22.9 and 23.1 vs 17.2 kp h/cm2; p=0.0001 and p=0.0002, respectively). The time to achieve a tenderness value at the injured site equivalent to that of the contralateral side at baseline (i.e., resolution of pain) was shorter in the active-treatment groups than in the placebo group (p<0.0001), and both escin-based gel preparations produced more rapid pain relief than the placebo gel, with no notable differences between the two active gels.50

Venous insufficiency

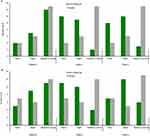

The efficacy of 1% escin+5% DEAS gel versus a placebo gel was compared in patients with stages 2 and 3 saphenous vein varices in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, clinical study.51 Patients were randomized to receive either topical escin-based gel (two times a day for 3 weeks) or placebo, and the principal outcome measure was the improvement in blood flow or perfusion, quantitatively assessed as refilling time on days 14 and 28, determined by LRR before treatment. Patients were also questioned regarding the main symptoms of vein disease (heaviness in the legs, swelling in the evening, pain, burning feet, and itching). After 2 weeks of treatment, refilling time had significantly increased from baseline in the escin-treated group (from 10.2 to 24.4 s; p<0.001), indicating restored venous tone, while refilling time decreased in the placebo-treated group from 14.9 to 11.7 s (Figure 7).47 Evaluation of subjective symptoms showed a very close correlation with the results of the LRR, with an improvement in overall symptom scores observed with escin-based gel after 14 days of treatment (Figure 8A and B).51

|

Figure 7 Refilling time after topical application of escin-based gel or placebo in patients with saphenous vein varices (p<0.001 at week 2). Copyright ©1988. Med Welt. Reproduced from Hoffmann J, Day U-H, Schneider B, Böhnert K-J. Percutaneous treatment of chronic venous insufficiency with an aescin-containing gel. A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind trial. Med Welt. 1988; 39:951–955.51 |

|

Figure 8 Changes in (A) heaviness in the legs (B) and swelling in the evening symptom scores after topical application of escin-based gel or placebo in patients with saphenous vein varices. Copyright ©1988. Med Welt. Reproduced from Hoffmann J, Day U-H, Schneider B, Böhnert K-J. Percutaneous treatment of chronic venous insufficiency with an aescin-containing gel. A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind trial. Med Welt. 1988; 39:951–955.51 |

Tolerability

A meta-analysis of studies using a range of oral escin preparations demonstrated that these products were well tolerated, with no severe adverse events reported.52 The pooled incidence of any adverse event was similar with escin (14.4%) and placebo (12.4%), and these events were mild and transient. The most common adverse events were mild gastrointestinal disorders (constipation, diarrhea, vomiting, and nausea), headache, dizziness, flushing, itching, and fatigue.52

In clinical studies, escin-based gel was rated as having excellent or good tolerability by >85% of patients who were assigned to topical administration of escin-based gel.49,50

Conclusion

Several decades of research have demonstrated the anti-inflammatory, anti-edematous, venotonic, and endothelial protective properties of escin, and shed light on the underlying mechanisms by which escin exerts these effects. Escin, as an oral formulation or a topical gel, reduces edema and increases venous tone, producing measurable improvements in venous hemodynamics, both in patients with blunt injury and those with CVI. Further clinical studies of escin are needed to demonstrate these properties in larger patient populations.

Abbreviations

AUC, the area under the curve; CVI, chronic venous insufficiency; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; CoCl2, cobalt chloride; F, bioavailability; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell; IV, intravenous; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; LRR, light reflection rheography; MRT, mean residence time; PECAM, platelet endothelial cell-adhesion molecule; PG, prostaglandin; PLA2, phospholipase A2; PSNA, sulfated escin with heparinoid properties; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; t1/2, terminal phase half-life; VCAM-1, vascular cell-adhesion molecule 1.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded with an educational grant by Meda Pharma SpA, a Mylan Company. I would like to thank Marion Barnett who provided medical writing assistance for the first draft of this manuscript on behalf of Springer Healthcare Communications. This medical writing assistance was funded by Meda Pharma SpA.

Author contributions

The author contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Luca Gallelli has received consultant fees or has served as speaker/board member for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Pfizer, Mylan, Meda, and Zambon. The author reports no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Eberhardt RT, Raffetto JD. Chronic venous insufficiency. Circulation. 2014;130(4):333–346. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006898

2. Renkin EM. Cellular aspects of transvascular exchange: a 40-year perspective. Microcirculation. 1994;1(3):157–167.

3. Arnould T, Janssens D, Michiels C, Remacle J. Effect of aescine on hypoxia-induced activation of human endothelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;315(2):227–233. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00645-0

4. Montopoli M, Froldi G, Comelli MC, Prosdocimi M, Caparrotta L. Aescin protection of human vascular endothelial cells exposed to cobalt chloride mimicked hypoxia and inflammatory stimuli. Planta Med. 2007;73(3):285–288. doi:10.1055/s-2007-967118

5. Arcelus A, Caprini JA. Non-operative treatment of chronic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Tech. 2002;26(3):231–238.

6. Bombardelli E, Morazzoni P, Griffini A. Aesculus hippocastanum L. Fitoterapia. 1996;67(6):483–511.

7. Chauhan R, Ruby K, Dwivedi J. Golden herbs used in piles treatment: a concise report. Int J Drug Dev Res. 2012;4(4):50–68.

8. European Medicines Agency. Assessment report on Aesculus Hipoocastanum L., semen; 2009. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/herbal-report/assessment-report-aesculus-hippocastanum-l-semen_en.pdf.

9. Sirtori CR. Aescin: pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic profile. Pharmacol Res. 2001;44(3):183–193. doi:10.1006/phrs.2001.0847

10. Diehm C, Vollbrecht D, Amendt K, Comberg HU. Medical edema protection–clinical benefit in patients with chronic deep vein incompetence. A placebo controlled double blind study. Vasa. 1992;21(2):188–192.

11. Diehm C, Trampisch HJ, Lange S, Schmidt C. Comparison of leg compression stocking and oral horse-chestnut seed extract therapy in patients with chronic venous insufficiency. Lancet. 1996;347(8997):292–294. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90467-5

12. Lorenz D, Marek ML. [The active therapeutic principle of horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum). Part 1. Classification of the active substance]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1960;10:263–272. [Article in German].

13. Pietta P, Mauri PJ. High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of β-escin. J Chromatogr. 1989;478:259–263. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(01)84394-6

14. Henschler D, Hempel K, Schultze B, Maurer W. [The pharmakokinetics of escin]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1971;21(11):1682–1692. [Article in German].

15. Meyer-Bertenrath J, Kaffarnik H. [Enteral resorption of aescin]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1970;20(1):147–148. [Article in German].

16. Madaus R, Erhring H, Winkler W. Reabsorbable aescin composition and method of making. US Patent Application: US3238104A. 1963. Available from: http://patents.google.com/patent/US3238104A/en.

17. Michiels C, Arnould T, Knott I, Dieu M, Remacle J. Stimulation of prostaglandin synthesis by human endothelial cells exposed to hypoxia. Am J Physiol. 1993;264(4 Pt 1):C866–c874. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.4.C866

18. Arnould T, Michiels C, Remacle J. Increased PMN adherence on endothelial cells after hypoxia: involvement of PAF, CD18/CD11b, and ICAM-1. Am J Physiol. 1993;264(5 Pt 1):C1102–C1110. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.5.C1102

19. Dudek-Makuch M, Studzinska-Sroka E. Horse chestnut – efficacy and safety in chronic venous insufficiency: an overview. Braz J Pharmacogn. 2015;25(5):533–541. doi:10.1016/j.bjp.2015.05.009

20. Girerd RJ, Di Pasquale G, Steinetz BG, Beach VL, Pearl W. The anti-edema properties of aescin. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1961;133:127–137.

21. Hampel H, Hofrichter G, Liehn HD, Schlemmer W. [Pharmacology of aescin-isomers with special reference to alpha-aescin]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1970;20(2):209–215. [Article in German].

22. Rothkopf M, Vogel G. [New findings on the efficacy and mode of action of the horse chestnut saponin escin]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1976;26(2):225–235. [Article in German].

23. Rothkopf M, Vogel G, Lang W, Leng E. Animal experiments on the question of the renal toleration of the horse chestnut saponin aescin. Arzneimittelforschung. 1977;27(3):598–605. [Article in German].

24. Facino RM, Carini M, Stefani R, Aldini G, Saibene L. Anti-elastase and anti-hyaluronidase activities of saponins and sapogenins from Hedera helix, Aesculus hippocastanum, and Ruscus aculeatus: factors contributing to their efficacy in the treatment of venous insufficiency. Arch Pharm (Weinheim). 1995;328(10):720–724.

25. Zhao SQ, Xu SQ, Cheng J, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of external use of escin on cutaneous inflammation: possible involvement of glucocorticoids receptor. Chin J Nat Med. 2018;16(2):105–112. doi:10.1016/S1875-5364(18)30036-0

26. Xin W, Zhang L, Sun F, et al. Escin exerts synergistic anti-inflammatory effects with low doses of glucocorticoids in vivo and in vitro. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(4):272–277. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2010.08.013

27. Wang T, Zhao S, Wang Y, et al. Protective effects of escin against indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer in mice. Toxicol. 2014;24(8):560–566.

28. Annoni F, Mauri A, Marincola F, Resele LF. [Venotonic activity of escin on the human saphenous vein]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1979;29(4):672–675. [Article in German].

29. Longiave D, Omini C, Nicosia S, Berti F. The mode of action of aescin on isolated veins: relationship with PGF2 alpha. Pharmacol Res Commun. 1978;10(2):145–152.

30. Brunner F, Hoffmann C, Schuller-Petrovic S. Responsiveness of human varicose saphenous veins to vasoactive agents. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;51(3):219–224. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2001.00334.x

31. Bougelet C, Roland IH, Ninane N, Arnould T, Remacle J, Michiels C. Effect of aescine on hypoxia-induced neutrophil adherence to umbilical vein endothelium. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;345(1):89–95. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01616-6

32. Carrasco OF, Vidrio H. Endothelium protectant and contractile effects of the antivaricose principle escin in rat aorta. Vascul Pharmacol. 2007;47(1):68–73. doi:10.1016/j.vph.2007.04.003

33. Domanski D, Zegrocka-Stendel O, Perzanowska A, et al. Molecular mechanism for cellular response to beta-escin and its therapeutic implications. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164365. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164365

34. Wang X-H, Xu B, Liu J-T, Cui J-R. Effect of beta-escin sodium on endothelial cells proliferation, migration and apoptosis. Vascul Pharmacol. 2008;49(4–6):158–165. doi:10.1016/j.vph.2008.07.005

35. Lang W, Mennicke WH. [Pharmacokinetic studies on triatiated aescin in the mouse and rat]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1972;22(11):1928–1932.

36. Wu X-J, Zhang M-L, Cui X-Y, et al. Comparative pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of escin Ia and isoescin Ia after administration of escin and of pure escin Ia and isoescin Ia in rat. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139(1):201–206. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.11.003

37. Lang W. [Percutaneous absorption of 3H-aescin in mice and rats]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1974;24(1):71–76. [Article in German].

38. Lang W. Studies on the percutaneous absorption of 3H-aescin in pigs. Res Exp Med (Berl). 1977;169(3):175–187.

39. Stenton SB, Bungard TJ, Ackman ML. Interactions between warfarin and herbal products, minerals, and vitamins: a pharmacist’s guide. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2001;54:186–192.

40. Anonymous. Aesculus hippocastanum (horse chestnut). Alt Med Rev. 2009;14(3):278–283.

41. Hernandez Carbajal B, Bravo Bernabe PA, Cruz Cruz M, Fernandez Garcia A, Zarraga Cobrales J. Clinical trials of treatment with amorphous aescin (reparil sugar coated tablets) in 100 patients with post-plaster and post-traumatic edema, 20 of such patients being given placebo. Madaus report; 1971.

42. Tsuyama N. Clinical evaluation of the anti-swelling drug A-4700 (reparil tablet) in the orthopaedic field. Clin Eval. 1977;5(3):535–575.

43. Hoffmann J, Day U-H, Schneider B, Böhnert K-J. Clinical trial of reparil coated tablets on patients with chronic venous insufficiency. Med Welt. 1988;39:945–950.

44. Vasquez Camacho L. A double-blind investigation of certain disorders of the veins of the pelvis and legs. MMW Munch Med Wochenschr. 1975;117(2):108–111.

45. Bahr R, Krosshaug T. Understanding injury mechanisms: a key component of preventing injuries in sport. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(6):324–329. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2005.018341

46. Serra MB, Barroso WA, da Silva NN, et al. From inflammation to current and alternative therapies involved in wound healing. Int J Inflam. 2017;2017:3406215. doi:10.1155/2017/3406215

47. Rothhaar J, Thiel W. [Percutaneous gel therapy of blunt athletic injuries]. Med Welt. 1982;33(27):1006–1010. [Article in German].

48. Bonnekoh A, Rost R, Völker K, Giannetti BM, Bulitta M, Ley F. Double-blind controlled clinical trial comparing an aescin combination gel with diclofenac diethylamine salt gel for efficacy and tolerability in volunteers with injection-induced haematoma. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 1992;43(3):1–10.

49. Pabst H, Segesser B, Bulitta M, Wetzel D, Bertram S. Efficacy and tolerability of escin/diethylamine salicylate combination gels in patients with blunt injuries of the extremities. Int J Sports Med. 2001;22(6):430–436. doi:10.1055/s-2001-16251

50. Wetzel D, Menke W, Dieter R, Smasal V, Giannetti B, Bulitta M. Escin/diethylammonium salicylate/heparin combination gels for the topical treatment of acute impact injuries: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, multicentre study. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(3):183–188. doi:10.1136/bjsm.36.3.183

51. Hoffmann J, Day U-H, Schneider B, Böhnert K-J. [Percutaneous treatment of chronic venous insufficiency with an aescin-containing gel. A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind trial]. Med Welt. 1988;39:951–955. [Article in German].

52. Siebert U, Brach M, Sroczynski G, Berla K. Efficacy, routine effectiveness, and safety of horsechestnut seed extract in the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and large observational studies. Int Angiol. 2002;21(4):305–315.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.