Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 10

Elderly care recipients’ perceptions of treatment helpfulness for depression and the relationship with help-seeking

Authors Atkins J, Naismith S, Luscombe G, Hickie I

Received 26 June 2014

Accepted for publication 14 August 2014

Published 20 January 2015 Volume 2015:10 Pages 287—295

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S70086

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Walker

Joanna Atkins,1 Sharon L Naismith,1 Georgina M Luscombe,2 Ian B Hickie1

1Brain and Mind Research Institute, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; 2School of Rural Health, Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney, Orange, NSW, Australia

Objective: This study aims to examine perceptions of the helpfulness of treatments/interventions for depression held by elderly care recipients, to examine whether these beliefs are related to help-seeking and whether the experience of depression affects beliefs about treatment seeking, and to identify the characteristics of help-seekers.

Method: One hundred eighteen aged care recipients were surveyed on their beliefs about the helpfulness of a variety of treatments/interventions for depression, on their actual help-seeking behaviors, and on their experience of depression (current and past).

Results: From the sample, 32.4% of the participants screened positive for depression on the Geriatric Depression Scale, and of these, 24.2% reported receiving treatment. Respondents believed the most helpful treatments for depression were increasing physical activity, counseling, and antidepressant medication. Help-seeking from both professional and informal sources appeared to be related to belief in the helpfulness of counseling and antidepressants; in addition, help-seeking from informal sources was also related to belief in the helpfulness of sleeping tablets and reading self-help books. In univariate analyses, lower levels of cognitive impairment and being in the two lower age tertiles predicted a greater likelihood of help-seeking from professional sources, and female sex and being in the lower two age tertiles predicted greater likelihood of help-seeking from informal sources. In multivariate analyses, only lower levels of cognitive impairment remained a significant predictor of help-seeking from professional sources, whereas both lower age and female sex continued to predict a greater likelihood of help-seeking from informal sources.

Conclusion: Beliefs in the helpfulness of certain treatments were related to the use of both professional and informal sources of help, indicating the possibility that campaigns or educational programs aimed at changing beliefs about treatments may be useful in older adults.

Keywords: older adults, help-seeking, depression, prevalence, perceptions of treatments

Introduction

The perceptions older people have about the potential helpfulness of interventions for depression are important, as they are likely to influence how individuals respond to their own depression and whether they seek treatment.1–3 Early help-seeking for depression is important and improves the long-term outcome of depression,4 and there is good evidence for effective psychological and pharmacological treatments for older people with depression.5,6 Untreated depression in older people has a number of consequences, including increased mortality,7,8 poorer functional outcomes,9–11 and reduced quality of life12,13 and is an independent risk factor for developing dementia.14

A number of studies have shown that older people use mental health services at a lower rate than the general population despite having high need for such services.15–18 This low rate of service use may, in part, be a result of poor detection and treatment rates within aged care settings.19,20 However, more recent studies indicate the situation is improving. For example, Levin et al21 found depression diagnosis rates of 48% in nursing home residents, and of these residents, 74% were receiving antidepressants. A study examining the characteristics of first-time admissions to nursing homes22 found that numbers identified with depression increased from 11% in 1999 to 16% in 2005, and that antidepressant use increased from 78% to 82%. A study of long-stay residents in nursing homes23 found that depression diagnosis increased from 34% in 1999 to 52% in 2007, and antidepressant use increased from 71% to 83% during the same period. These increases are attributed to improved depression detection, rather than increases in prevalence.

Several studies have examined the characteristics associated with help-seeking in older people. Elderly help-seekers have been found to have poorer psychological well-being, to have experienced more stressful life events and physical health problems, perceived themselves to have lower levels of social support, to be better educated, to live in capital cities, and to be more likely to be widowed, divorced, or separated and women.16,24–28

In terms of treatment preferences, a number of studies have shown that older respondents are less likely to rate professional sources of help, help from family or friends, or herbal medicines and vitamins as helpful and to rate pain killers, tranquilizers, cutting out alcohol, and help from the clergy or prayer more positively.3,18,29–35 In contrast, studies of the general public have found high levels of support for professional sources of help such as antidepressants and psychotherapy,31,36 as well as for increasing physical activity.

Previous research has focused on the attitudes toward help-seeking of community-dwelling elderly3,29,30,37 and home health care patients,34,38 and not the views of elderly care recipients in institutional settings. As depression is much more prevalent in residential settings,39,40 it is important to assess the views of these care recipients, particularly as preferred sources of treatment may not be available in institutional settings. The current study attempts to address this gap in the literature and aims to examine demographic characteristics of the sample, rates of depression and treatment for depression in the current sample, preferred sources of help, the perceptions of elderly care recipients about the helpfulness of a variety of treatments/interventions for depression, whether experience of depression and receiving treatment for depression affect beliefs in the helpfulness of treatments, whether beliefs about treatment are related to help-seeking from professional and informal sources, and the characteristics of elderly care recipients that predict help-seeking.

Methods

Sample

The sample consisted of 118 aged care recipients, aged 60 years and older, from four different types of aged care services: residential settings, including high care (one nursing home) and low care (two hostels), and community settings, including self-care (one retirement village) and community care (home care services), from the Sydney Metropolitan area. In Australia, nursing home accommodation is provided for care recipients with complex, ongoing needs, and hostel accommodation is provided for those with low support needs but who require some assistance with activities of daily living. Residents of self-care facilities are required to be in good health and to be able to manage their own care needs, whereas recipients of community care services often have high support needs and require assistance with activities of daily living in their own home. Participants were required to be fluent in English, without a severe cognitive impairment (defined as a Clinical Dementia Rating Scale score >2),41 not to be subject to guardianship orders, and free from significant sensory limitations (ie, able to read the study information and hear and respond to the survey questions).

Survey

A survey was compiled from a selection of questions from the International Depression Literacy Survey42 and the beyondblue depression monitor survey43 and was administered to participants in person by the first author.

The survey measured:

- Demographic variables: sex, age, years of schooling, type of care

- Depression status: lifetime experience of depression (self-reported), current experience of depression (aged care recipients were screened for depression using the Geriatric Depression Scale 15-item version [GDS-15]44 and were considered depressed if they scored five or more on this scale; this cutoff point has been used in a number of studies45,46 and is considered preferable to lower cutoff points for research studies46), and current treatment for depression (self-reported)

- Perceptions of the helpfulness of a variety of treatments/interventions for depression: for example, brief counseling, antidepressant medication, reading about people with similar problems, natural remedies, becoming more physically active, having an occasional alcoholic drink, reading self-help books, long-term counseling; response categories were helpful, harmful, neither, never heard of it, and do not know

- Help-seeking from professional sources: respondents were asked to identify, from a list provided, those from whom they had sought help, including counselor, family doctor, pharmacist, psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, welfare officer, another health professional, or none of the above, as well as informal sources such as acupuncturist; clergy, priest, or other religious person; personal trainer or exercise manager; family; friends; naturopath or herbalist; relaxation instructor; traditional healer; another health professional; or none of the above

- Cognitive impairment: measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale,41 which is based on clinically validated diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease.47

Ethics

Ethics approval to conduct the project was granted by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee. Participants were given a written information statement about the research and had the opportunity to discuss the study with the researcher before giving their informed consent to participate.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19. For analysis of the questions on beliefs about the helpfulness of treatments/interventions for depression, variables have been recoded into the dichotomous variables “helpful” and “all other responses.” Chi-squared analyses (or likelihood ratios where cell counts were low) were used for categorical variables, and Mann–Whitney U-tests were used for skewed continuous variables. For analysis of those who reported receiving treatment for depression by GDS categories, GDS-15 scores were recoded into the categories of no depression (0–4), mild depression (5–9), and moderate to severe depression (10–15).48 Age was recoded into tertiles for demographic comparisons. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of ever having sought professional or informal help for depression. These analyses were restricted to those care recipients who acknowledged ever having experienced symptoms of depression. For these analyses, type of care was recoded into the dummy variables: high care versus all other types of care, low care versus all other types of care, self-care versus all other types of care, and community care versus all other types of care. Age tertiles were recoded into the dummy variables: first tertile versus the other two tertiles, second tertile versus the other two tertiles, and third tertile versus the other two tertiles. All analyses used two-tailed tests and a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Demographics

As shown in Table 1, the majority of care recipients were women (72.0%), and their mean age was 81.3 years (standard deviation, 7.0). The mean number of years of schooling was 10.3 years (standard deviation, 2.3).

| Table 1 Demographic characteristics of sample and depression status |

Experience of depression

Of the total sample (n=118), 105 patients had complete GDS-15 scores. Of these patients, 32.4% (n=34) screened positive for current depression. Of the 117 who answered the question relating to lifetime experience of depression, 48.7% (n=57) reported having experienced symptoms of depression at some point in their lives. Of those who answered the questions about treatment (n=101), 13.9% (n=14) reported currently receiving treatment for depression: 8.8% (6/68) of those without depression (GDS, 0–4), 22.2% (6/27) of those with mild depression (GDS, 5–9), and 33.3% (2/6) of those with moderate to severe depression (GDS, 10–15). In summary, only approximately a quarter (24.2%; 8/33) of those with depression reported receiving treatment. All reported treatments were pharmaceutical: antidepressants (84.6%, 11/13), anxiolytic medication (7.7%, 1/13), and anti-psychotic medication (7.7%, 1/13). Those from high care were significantly more likely to be depressed (41.2% compared with 32.4% of community care respondents, 23.5% of low care, and 2.9% of self-care; χ2=20.5; df=3; P<0.01). There were no sex differences in likelihood of being depressed, although this is probably because of the small sample size and lack of statistical power, as women were more than twice as likely as men to have a GDS-15 score of five or more (67.6% compared with 32.4%).

Preferred sources of help

Of those who said they had experienced depression at some point in their lives, 9.4% (5/53) said they sought help only from professional sources, 17.0% (9/53) only from informal sources, and 54.7% (29/53) from both professional and informal sources, and 18.9% (10/53) did not seek help from any source. As shown in Table 2, the most common sources of professional help were the family doctor (46.3%; 25/54), psychiatrist (24.1%; 13/54), and counselor (9.3%; 5/54). More than one third (35.2%; 19/54) of care recipients had not sought any form of professional help. Care recipients were most likely to seek informal help from their family (45.3%; 24/53), friends (37.7%; 20/53), or clergy (13.2%; 7/53). More than a quarter of care recipients had not spoken to any informal source about their depression (30.2%; 16/53). There were no differences in terms of help-seeking from professional sources by type of care or sex, but women were more likely than men to say they had sought help from informal sources (77.8% compared with 22.2%; likelihood ratio =3.9; df=1; P=0.05). In terms of age, those in the highest age tertile were least likely to have sought help either from professional (likelihood ratio =6.5; df=2; P=0.04) or informal (likelihood ratio =8.9; df=2; P=0.01) sources.

| Table 2 Help-seeking sources |

Perceptions of the helpfulness of certain treatments/interventions for depression

As shown in Table 3, the most helpful treatments/interventions were seen to be becoming more physically active (78.6%; 88/112), brief counseling (73.9%; 85/115), long-term counseling (62.5%; 70/112), and antidepressants (60.2%; 68/113), and the least helpful treatments/interventions were having an occasional alcoholic drink (36.6%; 41/112) and sleeping tablets/sedatives (40.4%; 46/114).

The only demographic differences in beliefs about treatment were for age, with those in the highest age tertile least likely to believe that sleeping tablets/sedatives (χ2=6.9; df=2; P=0.03) or reading about people with similar problems and how they dealt with them (χ2=9.05; df=2; P=0.01) would be helpful.

Experience of depression and belief in treatments/interventions

Current experience of depression and belief in treatments/interventions

There were no significant differences in beliefs in the helpfulness of any of the types of treatments/interventions for depression between those who were and those who were not currently experiencing depression according to the GDS-15 (n=103).

Lifetime experience of depression and belief in treatments/interventions

Those care recipients who reported that they had experienced symptoms of depression at some point in their lives were significantly more likely to believe in the helpfulness of becoming more physically active than those who said they had never been depressed (87.3% compared with 70.2%; χ2=4.9; df=1; P=0.03; n=112).

Currently receiving treatment for depression and belief in treatments/interventions

There were no significant differences in beliefs about treatments for those who were and those who were not receiving treatment for depression.

Beliefs about the helpfulness of treatments and actual help-seeking from professional and informal sources

Those who thought that brief counseling (likelihood ratio =9.5; df=1; P<0.01) and antidepressants (χ2=5.1; df=1; P=0.02) were helpful were significantly more likely to have sought help from professional sources for depression than those who did not believe these treatments to be helpful.

Those who thought that long-term counseling (χ2=4.0; df=1; P=0.05), reading self-help books (χ2=4.3; df=1; P=0.04), sleeping tablets/sedatives (χ2=7.0; df=1; P<0.01), and antidepressants (likelihood ratio =4.5; df=1; P=0.03) were helpful were significantly more likely to have sought help for depression from informal sources than those who did not believe these treatments to be helpful.

Characteristics of treatment seekers

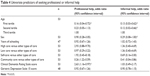

To ascertain the characteristics associated with help-seeking from professional sources, the following factors were used in univariate binary logistic regression analyses: age dummy variables (first tertile versus the other two tertiles; second tertile versus the other two tertiles, and third tertile versus the other two tertiles), sex, years of schooling, type of care dummy variables (high care versus all other types of care, low care versus all other types of care, self-care versus all other types of care, and community care versus all other types of care), Clinical Dementia Rating Scale score, and GDS-15 score. As shown in Table 4, only lower levels of cognitive impairment (odds ratio [OR], 2.6; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2–6.0; P=0.02) and being in the bottom two age tertiles (OR, 5.46; 95% CI 1.37–21.79; P=0.02) predicted greater likelihood of treatment seeking. In multiple regression analyses, only Clinical Dementia Rating Scale score remained significant (OR, 2.24; 95% CI 1.01–4.95; P=0.05).

| Table 4 Univariate predictors of seeking professional or informal help |

The above factors were used in univariate binary regression analyses to determine the characteristics associated with help-seeking from informal sources. Female sex (OR, 0.29; 95% CI 0.08–1.00; P=0.05) and being in the two lower age tertiles (OR, 8.00; 95% CI 1.92–33.38, P=0.004) predicted greater likelihood of help-seeking from informal sources. In multiple regression analyses, both sex (OR, 0.23; 95% CI 0.05–0.95; P=0.04) and being in the lower two age tertiles remained significant (OR, 9.61; 95% CI 2.05–45.10; P=0.01).

Discussion

The study examined the prevalence, experience, and perceptions of treatment helpfulness of elderly care recipients in relation to depression. In addition, the link between receiving treatment for depression and depression severity was explored. The study also examined whether the experiences of depression and receiving treatment for depression were associated with perceptions about the helpfulness of treatments/interventions for depression.

Aged care recipients expressed relatively positive perceptions regarding professional treatments for depression including antidepressant medication and counseling (both brief counseling and long-term counseling), but in a smaller proportion than those held by the general public in the Pfizer36 and Highet et al31 studies. In the current study, respondents showed a marked preference for the informal approach of increasing physical activity, which is similar but again not as prevalent as the general public in the Pfizer36 and Highet et al31studies.

As with previous studies,30,31 older people in the present study showed a marked preference for receiving treatment from their general practitioner (GP), rather than specialist mental health services. This is probably because of the stigma associated with mental illness by older persons,49 rather than problems with access to mental health services. This places a high burden on primary health care and means older people may miss out on specialist services and providers that are more knowledgeable about appropriate treatments for this age group.16 This is important, as a number of studies have shown that when older people do receive treatment for depression, it is often not of an appropriate type or duration to be effective.50,51

Belief in the helpfulness of professional treatments for depression was related to actual help-seeking from both professional and informal sources. Lifetime experience of depression did not appear to be related to perceptions of the helpfulness of treatments/interventions for depression, with the exception of becoming more physically active, which was seen as helpful by a larger proportion of respondents compared with those who did not report experiencing depression. Other studies have found that experience with using mental health services did increase positive attitudes toward treatment and increased the likelihood of using them again.52–55 It should be noted that although a high proportion of participants expressed positive views on the helpfulness of counseling (both long and short term), rating it more highly than antidepressants, no participant actually reporting receiving counseling for depression, with the majority (around 85%) reporting receiving antidepressant medication. It is possible that counseling would be a more acceptable form of treatment for older persons living in residential settings and, therefore, should be an available option. In addition, evidence-based treatments such as problem-solving therapy, cognitive behavior therapy, and behavior modification programs could be introduced either on an individual or a group basis.

Lack of help-seeking may not be a result of a lack of willingness to seek help but, instead, a result of a lack of knowledge about mental health services and the types of treatment available.30 Education programs for elderly care recipients may be one way to overcome these barriers to mental health care.56,57 Other barriers include the stigma attached to mental disorders,49,58–60 lack of perceived need for mental health care,25,61 cost of treatment,30 belief that depression is a normal part of aging,62,63 attitudes of GPs and mental health professionals,64,65 and a self-reliant belief system.61,66

There are a number of ways these barriers may be overcome. For example, GPs need to be alert to the possibility of depression in aged care recipients and educated in the recognition of depression in this group, in which diagnosis can be difficult because of the overlap of symptoms with other conditions and because of patients presenting with somatic complaints rather than psychological symptoms.67 It is also important to educate care facility staff and family members of care recipients in depression awareness, as evidence suggests that professional help for depression is most likely to occur when a significant other person recommends help be sought.68,69 Programs that help to destigmatize mental disorders may help increase the likelihood of specialist mental health services being used by older persons.

In the current study, nearly a third of respondents were depressed, according to the GDS-15, with only around a quarter of those needing treatment reporting they were receiving it. Although this rate is low, it should be noted that that those with more severe depression were more likely to be receiving treatment, with a third of those experiencing moderate to severe depression receiving help compared with only 22% of those in the mild depression category. A small proportion (nearly 9%) of those in the no-depression category also reported receiving treatment suggesting the treatment was effective in reducing their depression to below case level or, alternatively, possible misdiagnoses of false-positives.

There are a number of limitations to this study. In practice, care recipients probably do not have access to a wide range of treatments for depression, not because of their own treatment preferences but because of the practices of their particular care facility or their GP. Care recipients’ use of treatments and lifetime experience of symptoms of depression were assessed through self-report, which may not accurately reflect actual use of those treatments or experience of symptoms. It would be useful to access objective measures about diagnosis and treatment of depression. This was a cross-sectional study, so it is not possible to ascertain the direction of the relationship between perceptions of helpfulness of interventions for depression and treatment seeking: whether having more positive beliefs about treatment means recipients are more likely to seek help or whether having sought help leads to more positive beliefs about treatment. In addition, the survey did not use a validated instrument for beliefs in the helpfulness of treatments, such as the Help-Seeking Attitudes Scale.56 It should also be noted that the sample size in the study was small, which may limit the applicability of the results obtained and mean that statistically significant findings may not necessarily be clinically significant.

More research is needed into ways to overcome barriers to help-seeking and treatment in elderly care recipients and in educating aged care facility staff and GPs to make a wider choice of treatments (not just antidepressants) available, particularly in relation to counseling, psychological interventions, and exercise programs, which have been shown to be effective ways of reducing depression for this age group.70–75 These forms of treatment may be considered more acceptable than medication by elderly care recipients and would reduce the effects of polypharmacy, which is particularly relevant in this age group, whose members are likely to be taking a number of different medications.76 As the majority of care recipients with depression are not receiving professional treatment, it might be useful to see what self-help strategies they are using to manage their depression and to examine the effectiveness of these strategies.77

The association between perceptions of the helpfulness of professional treatments and actual help-seeking behaviors is important, as it may mean that education programs for elderly care recipients aimed at encouraging positive beliefs about professional treatments for depression will have positive outcomes in terms of increased use of these treatments by this group.

Conclusion

There was a relationship between beliefs in the helpfulness of professional treatments and the use of help-seeking from both professional and informal sources, suggesting that campaigns or educational programs aimed at changing beliefs about treatments may be useful in older persons in residential care.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the staff and management of Wesley Care Services for their support and participation in the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Edlund MJ, Fortney JC, Reaves CM, Pyne JM, Mittal D. Beliefs about depression and depression treatment among depressed veterans. Med Care. 2008;46(6):581–589. | ||

Fischer W, Goerg D, Zbinden E. Determining factors and the effects of attitudes towards psychotropic medication. In: Guimon J, Fischer W, Sartorius N, eds. The Image of Madness: The Public Facing Mental Illness and Psychiatric Treatment. Basel: Karger; 1999. | ||

Fisher LJ, Goldney RD. Differences in community mental health literacy in older and younger Australians. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(1):33–40. | ||

Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF III, Bruce ML, et al; PROSPECT Group. Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(8):882–890. | ||

Bartels SJ, Dums AR, Oxman TE, et al. Evidence-based practices in geriatric mental health care: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26(4):971–990. | ||

Gatz M. Commentary on evidence-based psychological treatments for older adults. Psychol Aging. 2007;22(1):52–55. | ||

Penninx BW, Geerlings SW, Deeg DJ, van Eijk JT, van Tilburg W, Beekman AT. Minor and major depression and the risk of death in older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(10):889–895. | ||

Saz P, Dewey ME. Depression, depressive symptoms and mortality in persons aged 65 and over living in the community: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(6):622–630. | ||

Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Braam AW, Smit JH, Van Tilburg W. Consequences of major and minor depression in later life: a study of disability, well-being and service utilization. Psychol Med. 1997;27(6):1397–1409. | ||

Ormel J, Kempen GI, Deeg DJ, Brilman EI, van Sonderen E, Relyveld J. Functioning, well-being, and health perception in late middle-aged and older people: comparing the effects of depressive symptoms and chronic medical conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(1):39–48. | ||

Eisses AM, Kluiter H, Jongenelis K, Pot AM, Beekman AT, Ormel J. Risk indicators of depression in residential homes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(7):634–640. | ||

Unützer J, Patrick DL, Diehr P, Simon G, Grembowski D, Katon W. Quality adjusted life years in older adults with depressive symptoms and chronic medical disorders. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12(1):15–33. | ||

Borowiak E, Kostka T. Predictors of quality of life in older people living at home and in institutions. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2004;16(3):212–220. | ||

Naismith SL, Glozier N, Burke D, Carter P, Scott E, Hickie IB. Early intervention for cognitive decline and dementia: the potential benefits of targeting multiple interventions. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009;3:19–27. | ||

Byers AL, Arean PA, Yaffe K. Low use of mental health services among older Americans with mood and anxiety disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(1):66–72. | ||

Crabb R, Hunsley J. Utilization of mental health care services among older adults with depression. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62(3):299–312. | ||

Karlin BE, Norris MP. Public mental health care utilization by older adults. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33(6):730–736. | ||

Parslow RA, Jorm AF. Who uses mental health services in Australia? An analysis of data from the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(6):997–1008. | ||

Rovner BW, German PS, Brant LJ, Clark R, Burton L, Folstein MF. Depression and mortality in nursing homes. JAMA. 1991;265(8):993–996. | ||

Forsell Y, Jorm A, Winblad B. The outcome of depression and dysthymia in a very elderly population: Results from a three-year follow-up study. Aging Ment Health. 1998;2(2):100–104. | ||

Levin CA, Wei W, Akincigil A, Lucas JA, Bilder S, Crystal S. Prevalence and treatment of diagnosed depression among elderly nursing home residents in Ohio. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8(9):585–594. | ||

Fullerton CA, McGuire TG, Feng Z, Mor V, Grabowski DC. Trends in mental health admissions to nursing homes, 1999–2005. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(7):965–971. | ||

Gaboda D, Lucas J, Siegel M, Kalay E, Crystal S. No longer undertreated? Depression diagnosis and antidepressant therapy in elderly long-stay nursing home residents, 1999 to 2007. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):673–680. | ||

Jorm A. Characteristics of Australians who reported consulting a psychologist for a health problem: An analysis of data from the 1989–1990 National Health Survey. Aust Psychol. 1994;29(3):212–215. | ||

Klap R, Unroe KT, Unützer J. Caring for mental illness in the United States: a focus on older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(5):517–524. | ||

Olfson M, Pincus HA. Outpatient mental health care in nonhospital settings: distribution of patients across provider groups. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(10):1353–1356. | ||

Swartz MS, Wagner HR, Swanson JW, Burns BJ, George LK, Padgett DK. Administrative update: utilization of services. I. Comparing use of public and private mental health services: the enduring barriers of race and age. Community Ment Health J. 1998;34(2):133–144. | ||

Cuijpers P. Psychological outreach programmes for the depressed elderly: a meta-analysis of effects and dropout. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13(1):41–48. | ||

Farrer L, Leach L, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF. Age differences in mental health literacy. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):125. | ||

Robb C, Haley WE, Becker MA, Polivka LA, Chwa HJ. Attitudes towards mental health care in younger and older adults: similarities and differences. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7(2):142–152. | ||

Highet NJ, Hickie IB, Davenport TA. Monitoring awareness of and attitudes to depression in Australia. Med J Aust. 2002;176(suppl):S63–S68. | ||

Lauber C, Nordt C, Falcato L, Rössler W. Lay recommendations on how to treat mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36(11):553–556. | ||

Unützer J, Simon G, Belin TR, Datt M, Katon W, Patrick D. Care for depression in HMO patients aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(8):871–878. | ||

Fyffe DC, Brown EL, Sirey JA, Hill EG, Bruce ML. Older home-care patients’ preferred approaches to depression care: a pilot study. J Gerontol Nurs. 2008;34(8):17–22. | ||

Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Rodgers B, Pollitt P. Beliefs about the helpfulness of interventions for mental disorders: a comparison of general practitioners, psychiatrists and clinical psychologists. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31(6):844–851. | ||

Pfizer. Depressed Australia. West Ryde NSW: Pfizer Australia and Mental Health Council; 2004. | ||

Jorm AF, Korten AE, Rodgers B, et al. Belief systems of the general public concerning the appropriate treatments for mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32(8):468–473. | ||

Raue PJ, Weinberger MI, Sirey JA, Meyers BS, Bruce ML. Preferences for depression treatment among elderly home health care patients. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(5):532–537. | ||

Snowdon J, Fleming R. Recognising depression in residential facilities: an Australian challenge. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(3):295–300. | ||

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Depression in Residential Aged Care 2008–2012. Canberra: Australian Government; 2013. | ||

Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140(6):566–572. | ||

Hickie A M IB, Davenport TA, Luscombe GM, Rong Y, Hickie ML, Bell MI. The assessment of depression awareness and help-seeking behaviour: experiences with the International Depression Literacy Survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7(1):48. | ||

Highet NJ, Luscombe GM, Davenport TA, Burns JM, Hickie IB. Positive relationships between public awareness activity and recognition of the impacts of depression in Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(1):55–58. | ||

Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5(1–2):165–173. | ||

Moxon S, Lyne K, Sinclair I, Young P, Kirk C. Mental health in residential homes: A role for care staff. Ageing Soc. 2001;21(1):71–93. | ||

de Craen AJ, Heeren TJ, Gussekloo J. Accuracy of the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) in a community sample of the oldest old. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(1):63–66. | ||

Morris JC, McKeel DW Jr, Fulling K, Torack RM, Berg L. Validation of clinical diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1988;24(1):17–22. | ||

McDowell I, Newell C. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. | ||

Conner KO, Copeland VC, Grote NK, et al. Mental health treatment seeking among older adults with depression: the impact of stigma and race. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(6):531–543. | ||

Coyne J, Katz IR. Improving the primary care treatment of late life depression: progress and opportunities. Med Care. 2001;39(8):756–759. Editorial. | ||

Flint AJ. Pharmacologic treatment of depression in late life. CMAJ. 1997;157(8):1061–1067. | ||

Aupperle PM, Lifchus R, Coyne AC. Past utilization of geriatric psychiatry outpatient services by a cohort of patients with major depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;6(4):335–339. | ||

Gum AM, Areán PA, Hunkeler E, et al. Depression treatment preferences in older primary care patients. Gerontologist. 2006;46(1):14–22. | ||

Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(8):527–534. | ||

Lin P, Campbell DG, Chaney EF, et al. The influence of patient preference on depression treatment in primary care. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30(2):164–173. | ||

Mackenzie CS, Gekoski WL, Knox VJ. Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: the influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(6):574–582. | ||

Llewellyn-Jones RH, Baikie KA, Smithers H, Cohen J, Snowdon J, Tennant CC. Multifaceted shared care intervention for late life depression in residential care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1999;319(7211):676–682. | ||

Segal DL, Coolidge FL, Mincic MS, O’Riley A. Beliefs about mental illness and willingness to seek help: a cross-sectional study. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(4):363–367. | ||

Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al. Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(3):479–481. | ||

Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Friedman SJ, Meyers BS. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(12):1615–1620. | ||

Mackenzie CS, Pagura J, Sareen J. Correlates of perceived need for and use of mental health services by older adults in the collaborative psychiatric epidemiology surveys. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(12):1103–1115. | ||

Rojas-Fernandez CH, Miller LJ, Sadowski CA. Considerations in the treatment of geriatric depression: Overview of pharmacotherapeutic and psychotherapeutic treatment interventions. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2010;3(3):176–186. | ||

Law J, Laidlaw K, Peck D. Is depression viewed as an inevitable consequence of age? The “understandability phenomenon” in older people. Clin Gerontol. 2010;33(3):194–209. | ||

Hansson L, Jormfeldt H, Svedberg P, Svensson B. Mental health professionals’ attitudes towards people with mental illness: do they differ from attitudes held by people with mental illness? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;59(1):48–54. | ||

Reavley NJ, Mackinnon AJ, Morgan AJ, Jorm AF. Stigmatising attitudes towards people with mental disorders: a comparison of Australian health professionals with the general community. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(5):433–441. | ||

Nygren B, Aléx L, Jonsén E, Gustafson Y, Norberg A, Lundman B. Resilience, sense of coherence, purpose in life and self-transcendence in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(4):354–362. | ||

Gallo JJ, Rabins PV, Lyketsos CG, Tien AY, Anthony JC. Depression without sadness: functional outcomes of nondysphoric depression in later life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(5):570–578. | ||

Chadda RK, Agarwal V, Singh MC, Raheja D. Help seeking behaviour of psychiatric patients before seeking care at a mental hospital. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2001;47(4):71–78. | ||

Dew MA, Dunn LO, Bromet EJ, Schulberg HC. Factors affecting help-seeking during depression in a community sample. J Affect Disord. 1988;14(3):223–234. | ||

Gatz M, Fiske A. Aging women and depression. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2003;34(1):3–9. | ||

Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Treatments for later-life depressive conditions: a meta-analytic comparison of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1493–1501. | ||

Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Moore KA, et al. Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(19):2349–2356. | ||

Chen KM, Chen MH, Chao HC, Hung HM, Lin HS, Li CH. Sleep quality, depression state, and health status of older adults after silver yoga exercises: cluster randomized trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(2):154–163. | ||

Singh N, Clements K, Singh M. The efficacy of exercise as a long-term anti-depressant in elderly subjects: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol. 2001;56A(8):M497–M504. | ||

Sjösten N, Kivelä SL. The effects of physical exercise on depressive symptoms among the aged: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(5):410–418. | ||

Royal College of Physicians and Royal College of Psychiatrists. The Psychological Care of Medical Patients: A Practical Guide; 2003. Available from: http://.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/cr108.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2014. | ||

Jorm AF, Medway J, Christensen H, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Rodgers B. Public beliefs about the helpfulness of interventions for depression: effects on actions taken when experiencing anxiety and depression symptoms. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(4):619–626. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.