Back to Journals » Drug Design, Development and Therapy » Volume 14

Does an Earlier or Late Intravenous Injection of Ondansetron Affect the Dose of Phenylephrine Needed to Prevent Spinal-Anesthesia Induced Hypotension in Cesarean Sections?

Authors Qian J, Liu L, Zheng X, Xiao F

Received 12 April 2020

Accepted for publication 23 June 2020

Published 16 July 2020 Volume 2020:14 Pages 2789—2795

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S257880

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Manfred Ogris

Jing Qian,1 Lin Liu,1 Xiufeng Zheng,2 Fei Xiao1

1Department of Anesthesia, Jiaxing University Affiliated Women and Children Hospital, Jiaxing, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Obstetrics, Jiaxing University Affiliated Women and Children Hospital, Jiaxing, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Xiufeng Zheng

Department of Obstetrics, Jiaxing University Affiliated Women and Children Hospital, Jiaxing, People’s Republic of China

Tel +86573-83963131

Email [email protected]

Fei Xiao

Department of Anesthesia, Jiaxing University Affiliated Women and Children Hospital, Jiaxing, People’s Republic of China

Tel +86573-83963131

Email [email protected]

Background: There was controversy about ondansetron can reduce the incidence of spinal-induced hypotension and decrease the consumption of vasopressor in cesarean delivery with spinal anesthesia. We hypothesized that different timing of ondansetron administration may contribute to the controversy. Therefore, we aimed to determine the effect of different timing of ondansetron administration on the dose requirement of preventing phenylephrine via comparing the ED50 of prophylactic phenylephrine.

Methods: Seventy-five parturients were finally enrolled in this prospective, randomized, double-blinded dose finding study. Ondansetron or placebo was administered 5 min or 15 min before intrathecal injection. Up-down allocation method was used to determine the dose of prophylactic phenylephrine for each parturient in the three groups. The initial infusion rate of first patient was 0.5 μg/kg/min. Then, the rate for next patient was varied with increasing or decreasing of 0.05 μg/kg/min according to the response of the previous patient. An effective dose was defined as no hypotension occurred during the study period. An ineffective dose was defined as hypotension occurred during the study period. Study period in this study is from intrathecal injection to neonatal delivery. ED50 of phenylephrine infusion was calculated by probit regression.

Results: The ED50 of intravenous phenylephrine calculated by probit analysis was 0.33 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.38) μg/kg/min and 0.36 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.38) μg/kg/min in group A and B, and 0.41 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.44) μg/kg/min in group C for patients undergoing cesarean delivery with combined spinal-epidural anesthesia.

Conclusion: An earlier administration of 4 mg prophylactic ondansetron contributed no benefits for lowing the dose of prophylactic phenylephrine compared to a late administration, but can decrease the dose of preventing phenylephrine in patients undergoing cesarean delivery with combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. This finding may be useful for clinical practice and further studies.

Keywords: ondansetron, phenylephrine, cesarean delivery, spinal anesthesia, hypotension

Introduction

Ondansetron has been shown to reduce the incidence of spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension and the dose requirement of vasopressor needed to treat or prevent hypotension.1–5 However, there is some controversy surrounding this function of ondansetron.6–8 Different research conditions used in different studies may contribute to this controversy, such as the dose of ondansetron that was used and the timing of administration. Studies have already suggested that 4 mg of ondansetron is more effective in this context compared to other doses.3,4 To be effective in reducing the incidence of spinal-induced hypotension, ondansetron may require sufficient time to reach its peak pharmacodynamic effect. Therefore, we hypothesized that an earlier administration of ondansetron might be superior to a late administration before spinal injection in the prevention of spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension. The aim of this study was to determine the effects of different times of ondansetron administration on the dose required of prophylactic phenylephrine. The primary goal of this study was to compare the ED50 values of prophylactic phenylephrine at the different times used to administer ondansetron.

Methods

Trial Design

This is a prospective, randomized, double blinded dose finding study using up-down allocation method.

Enrollment

After obtaining approval from the Ethics Committee of Jiaxing University Affiliated Women and Children Hospital (no.20200007) and written informed consent from all study subjects, seventy-five patients were enrolled in this study. The inclusion criteria were as follows. Parturients were recruited for participation in this study who were classified as physical status I or II based on the criteria established by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). The parturients all were singleton pregnancies at term (≥37 weeks’ gestation) and scheduled for elective cesarean delivery. Exclusion criteria included contraindications to regional anesthesia, preeclampsia, diabetes, any other coexisting maternal disease, active or early labor, ruptured membranes, and placenta previa. This trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Randomization

All enrolled parturients were randomized to receive a 4 mg prophylactic dose of ondansetron 5 min or 15 min before spinal injection in group A and group B, respectively, or the same volume of saline in group C 15 min before spinal injection. Computer-generated random-number software (Microsoft Excel, Redmond, Washington, USA) was used to randomize the parturients. Ondansetron was delivered by a single anesthesiologist (F. Xiao) who knew the parturients’ grouping but was not involved in the patients’ blood pressure management. The parturients and the two study anesthesiologists (J. Qian and L. Liu) were blinded to the parturients’ grouping. The parturients’ demographic characteristics in each of the three groups were recorded.

Study Protocol

All parturients received no pre-medications. After arriving in the operating theater, standard monitoring assessments were applied, including non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP), heart rate (HR), peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), and electrocardiogram (ECG) and the data were recorded. The study drug or placebo was delivered to each parturient 5 min or 15 min before spinal induction via an 18G needle with peripheral venous access, which was created at the time of admission to the operating theater. The combined spinal-epidural technique was accomplished via the “needle-through-needle” technique at the L3-4 interspace with the parturient in a left lateral position. 10 mg of hyperbaric bupivacaine combined with 5µg sufentanil was administered over the course of 10 seconds after ascertaining the free flow of clear cerebrospinal fluid. Then, the parturient was placed in a supine position with approximately 15 degrees of left uterine displacement by means of a wedge, after an epidural catheter was placed 3–4 cm into the epidural space. A volume of 5 mL/kg 37°C lactated Ringer’s solution was infused over 20 min at the same time as the intrathecal injection.

While the intrathecal local anesthetic mixture was being injected, the prophylactic phenylephrine infusion was started. For each parturient in the three groups, the infusion dose was determined by an up-down allocation method. Therefore, as described in prior studies,9,10 an initial dose of phenylephrine at either 0.5µg/kg/min (5 mg of diluted into 50 mL) or varying doses of 0.05µg/kg/min was used. For instance, if the current dose was “n” µg/kg/min of phenylephrine, the dose of phenylephrine administered to the next parturient was decided by the response of the current dose. Therefore, if the response was effective, the dose for the next parturient would be “(n - 0.05)” µg/kg/min. If the response was ineffective, the dose for the next parturient would be “(n + 0.05)” µg/kg/min. An effective dose was defined as no hypotension occurred during the study period. Conversely, an ineffective dose was defined as the presence of hypotension during the study period. The study period in this study was defined as beginning at the time of intrathecal injection and ending at neonatal delivery.

Measurements

According to our prior study,11 the baseline systolic blood pressure (SBP) was defined as the mean value of three continuous measurements at 3-min intervals after the parturients had calmed down in the operating room. The SBP and HR were recorded at 1-min intervals during the period from spinal injection to neonatal delivery and then at 5-min intervals until the surgery was completed. Hypotension was defined as the SBP value that was less than 20% of the baseline SBP and was treated with 50µg of phenylephrine. Hypertension was defined as the SBP value that was greater than 20% of the baseline SBP and was treated by stopping the phenylephrine infusion. The phenylephrine infusion was restarted when the SBP fell to less than the baseline SBP again. Bradycardia was defined as an HR less than 50 bpm and was treated with 0.5 mg of atropine if it was accompanied by hypotension. The infusion was stopped if the bradycardia was not accompanied by hypotension.

The level of the sensory block was gently checked using the loss of pinprick sensation method at 2-min intervals along the medioventral line starting 10 min after the intrathecal injection, then performed at 5-min intervals. The maximum sensory block level was recorded. Surgery did not proceed if the sensory block level was less than T6. The surgical times including the time from uterine incision to delivery, time from spinal induction to delivery, and time from administration of ondansetron to spinal induction were recorded. Side effects, including hypotension, episodes of hypotension, hypertension, bradycardia, nausea, vomiting, and shivering, were noted. The outcomes of the newborn, such as 1 and 5 min Apgar scores and the pH value of umbilical artery blood, also were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to determine whether the data distribution was or was not normal. Normally distributed data such as the parturients’ demographic characteristics were presented as means ± SD and were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance. Non-normally distributed data such as the sensory block level and surgical times were presented as medians and ranges and were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical data such as kinds of incidence were presented as numbers (percentages) and were analyzed using chi-square tests. The ED50 for the phenylephrine infusion was calculated using probit regression. A comparison of the differences among groups used the methodology of overlapping confidence intervals, which used a P-value < 0.05 if the 83% CIs were non-overlapping.12 GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) and IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 17.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) were used to carry out the data analysis. A P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant (two-sided).

Sample Size Calculations

The sample size was determined for each group of 25 parturients according to a previously published method, which indicated that 20–40 individuals were required to provide a stabilized estimation of the median effective dose using the up-down allocation method.13 Moreover, according to prior studies, the sample size was regarded as sufficient when six pairs of reversals of sequence were obtained when the up-down allocation method was applied to evaluate the ED50.9,10,14 After the allocation of 25 parturients, we also obtained six pairs of reversals of sequence. Thus, the sample size was sufficient to calculate the ED50 in the current study.

Results

Eighty-two parturients, who underwent cesarean delivery, were enrolled and assessed for eligibility in this clinical trial. Seven individuals declined to participate. Seventy-five parturients completed the study and were included in the statistical analysis. The consort trial flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. No significant differences existed among the groups with respect to the parturients’ demographic characteristics and surgical times during the study period (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Characteristics of Patients and Sensory Block Level and Surgical Time |

|

Figure 1 CONSORT diagram. |

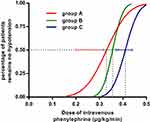

The results of the up-down allocations of intravenous phenylephrine infusion to prevent spinal-induced hypotension for the three groups are shown in Figure 2. The ED50 for prophylactic phenylephrine was 0.33 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.38) µg/kg/min and 0.36 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.38) µg/kg/min in groups A and B, respectively, and 0.41 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.44) µg/kg/min in group C for parturients undergoing cesarean delivery with combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. The ED50 was significantly lower in groups A and B compared to group C (P< 0.05), but similar between the two groups. The dose–response curves for the intravenous phenylephrine infusion and the probability of avoiding spinal-induced hypotension, which was determined based on probit analysis, are shown in Figure 3.

|

Figure 2 Individual response to intravenous dose of prophylactic phenylephrine. “●” represents effective and “○” represents ineffective. |

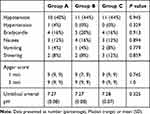

The maximum sensory block level was similar among all three groups, A, B, and C [T3 (T2~T4) vs T3 (T2~T4) vs T3 (T2~T4), respectively, P = 1.0]. Hypotensive episodes were less frequent in parturients in groups A and B compared to group C [2 (1~3) vs 2 (1~3) vs 4 (2~6), respectively, P < 0.05]. The incidence of side effects and data from the newborn outcomes (1 and 5 min Apgar scores and the pH value of umbilical artery blood) were similar among the three groups (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Incidence of Side Effects and Neonatal Outcomes |

Discussion

In this study, we found that the ED50 values of prophylactic phenylephrine were 0.33 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.38) µg/kg/min and 0.36 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.38) µg/kg/min with the administration of 4 mg of intravenous ondansetron 5 min or 15 min before intrathecal injection, respectively. The ED50 value of prophylactic phenylephrine was 0.41 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.44) µg/kg/min in the control group, which included parturients undergoing cesarean delivery with combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. Our results indicate there was no benefit to earlier administration of ondansetron in reducing the dose requirement of prophylactic phenylephrine in cesarean delivery. However, prophylactic administration of 4 mg of ondansetron could result in a lower dose of phenylephrine infusion needed to prevent spinal-induced hypotension. This finding may be useful for clinical practice because lowering the infusion dose of phenylephrine could overcome the adverse effects of phenylephrine infusion (decreasing in heart rate and cardiac output), especially when a large dose is administered.15,16

Results reported by some prior studies were similar to the observations reported in this study. El Khouly et al1 and Sahoo et al2 administered 4 mg of ondansetron as a preventive strategy to overcome spinal-induced hypotension in cesarean delivery. These two studies reported that the ondansetron administration could significantly improve the stability of the hemodynamics in the parturient and reduce the need for an intravenous vasopressor. Wang et al3 reported a dose-dependent study that used prophylactic ondansetron in this setting, and found that 4 mg of ondansetron was an effective and optimal dose for preventing maternal hypotension and decreased the amount of vasopressor that was needed during cesarean delivery. Moreover, two recently published meta-analyses conducted by Gao et al4 and Heesen et al5 reached a similar conclusion in that ondansetron as a 5-HT3 antagonist was an effective agent in reducing the incidence of spinal-induced hypotension and requirements for intravenous vasopressor in cesarean delivery. Our results further proved that prophylactic ondansetron could result in a reduced need for a prophylactic vasopressor.

The mechanism by which ondansetron prevents spinal-induced hypotension remains unknown. However, it is possible to inhibit the Bezold–Jarisch reflex (BJR) by blocking serotonin binding to 5-HT3 receptors in the left ventricle, and this could be the mechanism in this context.1–5,17,18

Not all studies showed that ondansetron could reduce spinal-induced hypotension and administration of vasopressor. Terkawi6 and his colleagues found that the administration of ondansetron neither stabilized the variations observed in hemodynamics nor reduced the needed levels of vasopressor that were administered. Similarly, Ortiz et al7 compared 2, 4, and 8 mg of ondansetron with a placebo and found that ondansetron had no pharmacological effect on reducing the incidence of spinal-induced hypotension or the amounts of vasopressor used in cesarean delivery. Oofuvong et al8 tried to find the minimal effective dose of ondansetron that would prevent spinal-induced hypotension, but failed to observe this effect. It is difficult to explain the inconsistencies observed in these previously published reports. However, in this study, we concluded that different times for the administration of ondansetron did not contribute to the observed inconsistency. Our observation provides necessary information for future studies.

It should be noted that the ED50 for prophylactic phenylephrine in this study was nearly 0.1µg/kg/min higher than in our prior study, in which we found that the ED50s for prophylactic phenylephrine were 0.32 and 0.24 µg/kg/min for preventing spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension in the control group and experimental group, respectively.19 The inconsistency of the ED50s between the two studies may be due to several protocol details, such as different intrathecal injection rates (10s vs over 15s) that subsequently resulted in different degrees of sympathetic blocks and a different incidence of hypotension and its severity. However, the significant differences between the experimental and control groups were similar in our two studies.

Limitations existed in this study. First, although the study had the power to calculate the ED50 for prophylactic phenylephrine, this still was a small sample size. Therefore, multicenter studies with larger sample sizes are needed in the future. Second, although we demonstrated that ondansetron could reduce the ED50 of prophylactic phenylephrine, the full dose-response of prophylactic phenylephrine (especially the ED95, which is more meaningful than ED50 in clinical practice) is still unclear. It is possible that the up-down allocation method could be used to deduce the ED95 for prophylactic phenylephrine, but it also could lack the ability to calculate the ED95 values accurately. Therefore, we did not report the ED95 for prophylactic phenylephrine in the current study.

In conclusion, an earlier administration of 4 mg prophylactic ondansetron contributed no effect on lowering the dose of prophylactic phenylephrine compared to a later administration. However, prophylactic ondansetron was able to decrease the dose of prophylactic phenylephrine in parturients undergoing cesarean delivery with combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. This finding may be useful for clinical practice and further studies.

Data Sharing Statement

The authors will share individual deidentified participant data such as blood pressure, side effects and characteristic of CSEA. No other study-related documents will be available. The data will be accessible 6 months after publication from http://www.chictr.org.cn.

Acknowledgments

The authors would thank all staff in the Department of Anesthesia and Operating Room of Jiaxing University Affiliated Women and Children Hospital, Jiaxing, China, for their help in this study. This study was supported by the Jiaxing Science and Technology Bureau Fund (2020AD30032).

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, revising the manuscript critically, read and approve the final draft of the manuscript for submission, gave final approval of the manuscript version to be published and agreed to be accountable for every step of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. El Khouly NI, Meligy AM. Randomized controlled trial comparing ondansetron and placebo for the reduction of spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension during elective cesarean delivery in Egypt. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;135:205–209. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.06.012

2. Sahoo T, SenDasgupta C, Goswami A, Hazra A. Reduction in spinal-induced hypotension with ondansetron in parturients undergoing caesarean section: a double-blind randomised, placebo-controlled study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2012;21:24–28. doi:10.1016/j.ijoa.2011.08.0023

3. Wang M, Zhuo L, Wang Q, et al. Efficacy of prophylactic intravenous ondansetron on the prevention of hypotension during cesarean delivery: a dose-dependent study. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:5210–5216.eCollection2014.

4. Gao L, Zheng G, Han J, Wang Y, Zheng J. Effects of prophylactic ondansetron on spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension: a meta-analysis. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2015;24:335–343. doi:10.1016/j.ijoa.2015.08.012

5. Heesen M, Klimek M, Hoeks SE, Rossaint R. Prevention of spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension during cesarean delivery by 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonists: a systematic review and meta-analysis and meta-regression. Anesth Analg. 2016;123:977–988. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001511

6. Terkawi AS, Tiouririne M, Mehta SH, Hackworth JM, Tsang S, Durieux ME. Ondansetron does not attenuate hemodynamic changes in patients undergoing elective cesarean delivery using subarachnoid anesthesia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40:344–348. doi:10.1097/AAP.0000000000000274

7. Ortiz-Gomez JR, Palacio-Abizanda FJ, Morillas-Ramirez F, et al. The effect of intravenous ondansetron on maternal haemodynamics during elective caesarean delivery under spinal anaesthesia: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2014;23:138–143. doi:10.1016/j.ijoa.2014.01.005

8. Oofuvong M, Kunapaisal T, Karnjanawanichkul O, Dilokrattanaphijit N, Leeratiwong J. Minimal effective weight-based dosing of ondansetron to reduce hypotension in cesarean section under spinal anesthesia: a randomized controlled superiority trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18:105. doi:10.1186/s12871-018-0568-7

9. Zhang YF, Xiao F, Xu WP, Liu L. Prophylactic infusion of phenylephrine increases the median effective dose of intrathecal hyperbaric bupivacaine in cesarean section: a prospective randomized study. Medicine. 2018;97:e11833. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011833

10. Xiao F, Xu W, Feng Y, et al. Intrathecal magnesium sulfate does not reduce the ED50 of intrathecal hyperbaric bupivacaine for cesarean delivery in healthy parturients: a prospective, double blinded, randomized dose-response trial using the sequential allocation method. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17:8. doi:10.1186/s12871-017-0300-z

11. Xiao F, Drzymalski D, Liu L, et al. Comparison of the ED50 and ED95 of intrathecal bupivacaine in parturients undergoing cesarean delivery with or without prophylactic phenylephrine infusion: a prospective, double-blind study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43:885–889. doi:10.1097/AAP.0000000000000850

12. Choi SC. Interval estimation of the LD50 based on an up-and-down experiment. Biometrics. 1990;46:485–492. doi:10.2307/2531453

13. Pace NL, Stylianou MP. Advances in and limitations of up-and-down methodology. Anesthesiol. 2007;107:9. doi:10.1097/01.anes.0000267514.42592.2a

14. Dixon WJ. Staircase bioassay: the up-and-down method. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1991;15:47–50. doi:10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80090-9

15. Kee WD. The use of vasopressors during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017;30:319–325. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000000453

16. Kinsella SM, Carvalho B, Dyer RA, et al. International consensus statement on the management of hypotension with vasopressors during caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2018;73:71–92. doi:10.1111/anae.14080

17. Terkawi AS, Mavridis D, Flood P, et al. Does ondansetron modify sympathectomy due to subarachnoid anesthesia? Meta-analysis, meta-regression, and trial sequential analysis. Anesthesiology. 2016;124:846–869. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000001039

18. Karacaer F, Biricik E, Ünal İ, Büyükkurt S, Ünlügenç H. Does prophylactic ondansetron reduce norepinephrine consumption in patients undergoing cesarean section with spinal anesthesia? J Anesth. 2018;32:90–97. doi:10.1007/s00540-017-2436-x

19. Xiao F, Wei C, Chang X, et al. A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blinded Study of the Effect of Intravenous Ondansetron on the Effective Dose in 50% of Subjects of Prophylactic Phenylephrine Infusions for Preventing Spinal Anesthesia-Induced Hypotension During Cesarean Delivery. Anesth Analg. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004534. Online ahead of print.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.