Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 10

Consumer views about aging-in-place

Authors Grimmer K, Kay D, Foot J, Pastakia K, Kennedy K

Received 17 June 2015

Accepted for publication 19 August 2015

Published 4 November 2015 Volume 2015:10 Pages 1803—1811

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S90672

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Walker

Karen Grimmer, Debra Kay, Jan Foot, Khushnum Pastakia

International Center for Allied Health Evidence, Sansom Institute, City East Campus, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA, Australia

Background: Supporting older people’s choices to live safely and independently in the community (age-in-place) can maximize their quality of life and minimize unnecessary hospitalizations and residential care placement. Little is known of the views of older people about the aging-in-place process, and how they approach and prioritize the support they require to live in the community accommodation of their choice.

Purpose: To explore and synthesize the experiences and perspectives of older people planning for and experiencing aging-in-place.

Methods: Two purposively sampled groups of community-dwelling people aged 65+ years were recruited for individual interviews or focus groups. The interviews were semistructured, audio-recorded, and transcribed. Themes were identified by three researchers working independently, then in consort, using a qualitative thematic analysis approach.

Results: Forty-two participants provided a range of insights about, and strategies for, aging-in-place. Thematic saturation was reached before the final interviews. We identified personal characteristics (resilience, adaptability, and independence) and key elements of successful aging-in-place, summarized in the acronym HIPFACTS: health, information, practical assistance, finance, activity (physical and mental), company (family, friends, neighbors, pets), transport, and safety.

Discussion: This paper presents rich, and rarely heard, older people’s views about how they and their peers perceive, characterize, and address changes in their capacity to live independently and safely in the community. Participants identified relatively simple, low-cost, and effective supports to enable them to adapt to change, while retaining independence and resilience. The findings highlighted how successful aging-in-place requires integrated, responsive, and accessible primary health and community services.

Keywords: functional decline, independence, aging-in-place, qualitative research

Background

Functional decline (FD) is characterized by the loss of physical, social, and/or thinking capacity.1–4 It is a correlate of aging, and generally impacts on older people’s capacity to live safely, independently, and with dignity in the community home of their choice. FD is sequelae of aging body systems, but is not inevitable.5,6 It can be prevented or delayed if detected early, and managed with careful, effective planning and targeted supports.4,7,8 To date, there is more emphasis in the literature on detecting and addressing established FD than on its earlier manifestations, prevention, and management. Many older people are well onto the trajectory of FD before they are first identified within the health system, and typically this occurs in unfamiliar environments such as hospital wards or emergency departments, after a health crisis.9,10 In this situation, plans put in place to address perceived loss of function may be irrelevant and ineffective, and the person’s FD too complex to be reversed at this point.8,11

The notion of early FD (insidious loss of function) has been discussed internationally as occurring in older people seemingly living without problems in their community home.4 Early FD may not have been detected at all by primary healthcare providers, but its manifestations (ie, depression, loneliness, anxiety, compromised nutrition and sleep patterns, confusion, reducing physical activity and muscle strength, or loss of interest in recreational activities) may be causing concern among older individuals and their families.1,3 A recent review of diagnostic literature for early FD12 found 107 psychometrically sound constructs of early FD. These constructs reflected medical status, performance capacity, participation, demographics, anthropometry, and relationships with health providers. However, few assessment tools were based on older people’s perspectives, rather, they reflected perspectives of health care providers and researchers on the nature and measures of FD. Consequently, most instruments were unidimensional12 and measured functional deficit rather than a consumer-informed, strengths-based approach to making accommodations and enabling achievement of the person’s functional goals.

Since the 1980s, the concept of “aging-in-place” has received increasing attention from service providers, policy makers, and researchers internationally.13–19 Surveys in many countries report that the desire of most older people is to continue to live independently in their community and to retain control, personal autonomy, flexibility, and lifestyle choices.20,21 Aging-in-place encapsulates endeavors to support older people in their preferred accommodation and communities for as long as possible.

As with many developed countries, the Australian lifespan is predicted to increase over the next decade as is the number of older Australians predicted to want to live independently in the community.22 Without evidence-based policies to provide the supports that older people need to live independently, the burden of managing unrecognized FD will fall onto scarce health and housing resources, when it will be too late to alleviate health and housing crises.23

The comprehensive review of aging-in-place literature conducted by Vasunilashorn et al13 highlighted the increasing volume of publications in this area. The majority of available policy and research literature addresses the environment and services provision for aging-in-place and reflects the perspectives of policy makers, service providers, and researchers. Within this literature, there is a notable gap in evidence informed directly by the consumers of aging-in-place efforts, and none found for Australian populations.13,24 There is a lack of knowledge about older people’s views of declining function, and how to effectively identify and manage this early, before significant FD has occurred, and within the context of successful aging-in-place.

The researchers for this study were from health, education, and social science backgrounds and had experience and training in consumer engagement, disability advocacy, epidemiology, and health services research. All had an interest in learning from older Australians about their perspectives on early FD, and how they perceived that this could be identified and addressed.

The aim of our overall study is to develop a consumer-informed framework for consumers and health and community services to identify early or anticipated signs of FD. This framework will be designed to assist consumers and service providers to plan and act on identified signs and thus enable people to successfully age-in-place. The first stage, detailed in this paper, aims at exploring and synthesizing the experiences and perspectives of older people to create a consumer-informed framework. The second stage uses Delphi method research to further develop and validate the framework.

Methods

Ethics

University of South Australia Human Research Ethics Committee approval was provided in January 2014 (number 0000031475).

Partnerships

The Research Center had an already well-established partnership with the Health Consumers Alliance of South Australia (HCA) and had worked previously with Council on the Aging, South Australia (COTA SA), both of whom agreed to advertize the opportunity for consumers to be study participants. A formal study partnership was also established with Adelaide Unicare, a university-linked corporate group that manages six general medical practices in South Australia.

Participants and participant recruitment

People aged 65+ years living independently in the South Australian community were selected as subjects. The first sample consisted of participants recruited purposively through Unicare Practice Managers and HCA staff who invited people aged 65+, known to their organizations, to join the study. Potential participants were provided with an information sheet and consent form. Researchers telephoned people who had agreed to be contacted, answered any questions, arranged an interview time, and finalized consent. Participants in this first sample were invited to undertake a second interview with a different interviewer, who was also a health practitioner, to explore the topic in further depth. A second purposive sample was recruited via invitations extended to members of COTA.

Interviews

Semistructured questions addressed older people’s perspectives of their own, and others’, aging-in-place and declining function. The interview questions were pilot tested with five people and no changes were required prior to data collection (Supplementary material). Participants were given the option of individual face-to-face or telephone interviews or a small focus group. Interviews or focus groups for all participants were conducted, according to participants’ choice, either in their homes, in GP surgeries, or another agreed location, such as a local coffee shop. Interviews were conducted by a researcher experienced in interviewing, and a second volunteer aged 65+ attended the first round of in-home interviews for safety/risk management. The interviews commenced with an explanation of the purposes of the study and questions allowed participants to describe and expand on issues that they considered important. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

All interview transcripts were carefully studied to inductively identify patterns of meaning. Members of the research team met to discuss meanings and categories within the data and thematic development, using hard copies of the transcripts. Themes regarding aspects of aging-in-place were identified that were important to older people, along with illustrative quotations. The themes were then reconsidered, within the context of the interview transcripts, to identify what they represented in terms of the characteristics of aging well in-place, and the areas of support considered by participants to be important for successful aging-in-place. Data saturation was considered to have occurred if no new themes arose from at least the final three interviews analyzed.25

Themes derived from the data were summarized and structured into a form that could be used in our next planned stage of Delphi research. As a form of member checking and to validate our qualitative analysis, participants were sent a follow-up letter with the summarized findings and invited to make further comment.

Results

Sample

All 23 people recruited via Unicare (six) and HCA (17) agreed to participate face to face: six individually, nine in a couple/with a family member, and the remaining eight via a focus group. Of the ten interviewees who agreed to a second interview, two were interviewed individually, four as couples, and four in a focus group. All 19 people who had responded to the invitation extended by COTA on our behalf were then interviewed individually: 17 via telephone and two face to face. Interview length ranged from 25 to 45 minutes, and the focus group ran for 80 minutes.

Participant characteristics

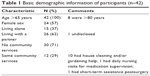

Table 1 summarizes demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Table 1 Basic demographic information of participants (n=42) |

Saturation

From the first sample of 23 participants, saturation occurred at the 15th interview, as little new information was subsequently provided. The interviews with COTA participants confirmed our initial findings and highlighted no new information. Moreover, when we “back checked” the derived themes and characteristics of successful aging-in-place across the initial transcripts,26 these were all evident within the first seven interviews.

Themes

The interviews afforded rich information that, when analyzed, provided three themes related to personal characteristics and eight key elements for successful aging-in-place.

Personal characteristics related to successful aging-in-place: independence, adaptability, and resilience

Independence: All of participants wanted to stay in the community home of their choice as long as they could, whether this was a larger family home or a smaller independent living option.

Going into a home? That’d be the end of me. And I mean it. [DKC]

And all were prepared to “put up” with some lifestyle limitations to retain independence.

I could get more help if I needed it, but I said no that’ll do for the moment. [DKD]

Adaptation: All could identify proactive steps they had taken to adapt their actions and environments to achieve their goals.

I mean I could do things and my strength’s gone a lot, but I try to work my way around things and figure out how to do them differently. [DKJ]

Resilience: All shared to a greater or lesser degree a sense of “getting on with it” in some way, and provided examples of resilience in the face of adversity.

It seems as if I just went to bed one night and I woke up the next day with problems. It all compounded fairly quickly, although I have a positive mental attitude and I don’t want it to beat me and I think that’s half the fight. [DKC]

Key elements related to successful aging-in-place (not in order of importance)

- Health: support for self-management, health professionals as needed.

There was a commonly expressed view that doctors are too busy and probably not the appropriate people to have the sort of conversations that would identify problems people were beginning to experience. Some participants proposed the idea of appropriate health professionals coming into the homes of lonely/isolated older people to check on them; support them to socialize; and to assist them to access support.After all our health-if you haven’t got your health, you can’t do anything. [FDM1]

- Information services: timely, accessible, online, face to face, one stop.

Participants indicated that timely information was critical to successful aging-in-place. They suspected that there was a lot of information available; however, it was rarely available when and how people needed it. Local libraries, pharmacies, and general practices were mentioned as potential, but not reliable nor always desirable, places for information dissemination. Participants wanted all relevant information available when they needed it, from a readily identifiable and accessible source, and in a variety of formats to suit individual needs (eg, face to face or online).

One person reported that he was waiting for his wife to go in for her next scheduled surgery because this was the only time he might have free to try to find out how to plan if he could not care for her sometime in the future.I’ve been fortunate enough to have a glimpse of some of the things that are available by chance and that might be because in the process of you being sick we’ve stumbled upon something. Usually it’s been a stumble it hasn’t been a direction from someone in the know and that’s led to something, which has led to something so that’s been great. [FDF]

I want to go around and try to find out what fall-back situations are available so that if I fall or something and got to go to hospital I can ring up and say “Right, now activate the plan that we’ve put in place. [FDA]

- Practical support: targeted, timely, self-directed, affordable.

Accessing practical support was considered essential. Some had neighborhood mutual support arrangements. All participants gave examples of when they or their peers needed support, and how success varied according to the person’s knowledge of what was available, eligibility, cost, and cultural fit, ie, whether they liked the manner in which the service was provided.

There was comment about how it can be easier to get regular support (eg, fortnightly cleaning) than odd job support (eg, getting a sliding door put back on its tracks) and that the need to get the little jobs done could be the most distressing. There was common mention of the difficulty of having work done promptly (eg, globes changed) except where residents were in accommodation where this was part of a maintenance contract; for some this was done as a fee for service, which could be expensive. Availability of care packages for personal support or carer respite were noted, as was the difficulty in fitting their priorities into the packages offered. They recommended flexibility in support arrangements as a priority.The people that they had didn’t want to work the hours that I wanted them to come. I didn’t want them to come at eight o’clock in the morning. You know, with having this condition in my spine, it takes me a little while to unwind in the morning. [KPA]

Couples provided clear information about how they could provide mutual assistance, with resultant challenges for both. Participants also spoke about the domino effect when a support mechanism that had been in place, and well used, was subsequently removed (ie, community bus/transport). Those affected felt let down and were often left to make their own arrangements, with nowhere to turn for advice. - Finance: subsidies for those in need.

The majority of participants talked about “making ends meet”, and disparities perceived between benefits afforded, for example, between self- and government-funded retirees.There’s people out there paying rent out of pension and that is their income. That must be impossible and it frightens me to think we might be one day. [DKT3]

There was a shared perception of many “schemes” that gave benefits to some groups but determining what was available and for whom was not easy. Some referred to the need to review current subsidy arrangements with current lifestyles in mind.It’s getting to the stage where if you haven’t got a computer you can’t communicate. How many of the aged can afford a computer and a mobile phone and a telephone and this and that? [DKT2]

Participants talked about contractors who were supposed to be providing services, for example, via the local council, overcharging older people because of perceived vulnerability, or because they were thought unlikely to complain. Many however had and were proud of their capacity to “fight back”, refusing (and therefore not accessing) the service.That’s another point isn’t it, being ripped off. [DKT1]

Internet banking and arranging Centrelink bill payments were suggested as potentially useful. People acknowledged that local libraries and councils sometimes offered technology training and noted that many people are not interested in these opportunities. Noninternet bankers had to leave the house to pay bills, or get money from the bank during business hours, and for some this was a physical challenge. - Keeping active: physically and mentally.

Most of our participants mentioned the importance of keeping physically and mentally active and how they achieved this.You want to stay active and stay at home, you’ve got to have some activity […] I make a rule that I stop work at four o’clock […] I find that I’m fully occupied around the house; whether I’m working in the shed or in the garden, or I go to gym down the Club; there’s always something to do. [DKM1]

Physical activity included walking to local shops, playing golf, and bike riding.I find that with tap dancing […] we’re none of us all that good anymore, but we enjoy it. Actually the best thing is the laughs we get, because we’re all so dreadful. [KPK]

Physical activity linked with shopping was seen as difficult because shopping needed to be transported, and this was often not possible when walking. Some capitalized on free delivery services. Internet shopping was mentioned as a solution; however, participants also noted that this meant that they did not need to go out, which could be considered counterproductive.

Keeping mentally active was noted often by our participants as being essential for maintaining healthy, safe, and independent living. Mental activities included having creative hobbies that required planning, working with their hands and organizing materials, undertaking activities that require problem solving, and being members of social groups.I find if you can keep an interest, have something that really interests you and as I said I’m very fond of all sports. I played netball myself up until I was 40 and I try and do crossword puzzles. [KPE]

- Company: community, family, and pets.

Socialization was considered to be important by most for healthy community aging, although some talked about the right to choose and not be forced into group activities.You don’t want to sit home locked in your house all day. That’s the main thing. [DKF]

One variant view was provided:(I’m) quite happy by myself. It’s about what you feel like doing […] I’m not interested in bowls and not interested in men’s sheds for two hours a week or something. [DKJ]

Socialization occurred in families and social groups (such as golfing, walking, and quilting), and people talked about valuing the reliability and frequency of these occasions. People talked about not canceling social engagements, even if they did not feel well, or the weather was not conducive to going out, because they valued the routine, and because it “helped others”.

Participation in day-time activities was not always seen as the cure for loneliness.A lot of them like myself find the weekends are very hard to take. [DKG]

- Transport: affordable, reliable, accessible.

People valued access to reduced fee taxis when they did need to go shopping to bring home larger quantities of goods, and living nearby to public transport was seen as a bonus. Some had made car pool arrangements, which were particularly useful for older people who did not drive, and could contribute financially to the trip.It’s a lot of money to just go to [the shops] and back so the ones that drive like myself we usually, if I decided to go somewhere I’ll go and say to a couple of the neighbors […] do you want to go there […] we try and run a car pool if we can. [DKG]

Several people talked about the value to them or others of community buses that collected people at regular times and locations, completing a loop to main shopping and business centers. The reliability of the community buses was queried by some who reported being stranded at shopping centers for several hours when the bus timetable was disrupted. - Safety: personal, house, and environmental safety and security.

Personal and physical safety was identified as a priority. Early recognition of the need for home assistance and aids, such as grab rails, steps/ramps, and nonslip surfaces was noted. Some recommended a regular safety audit of homes, for example, undertaken by local councils or service clubs, to identify opportunities to improve personal safety without the need for a “health” intervention (like to need to visit the GP to initiate such an intervention, possibly flagging unwanted conversations with family about the need to move into more supported care).

The need for personal security was mentioned. Some participants had developed informal security systems with their neighbors, such as leaving keys with each other, having signals such as raising or lowering blinds to indicate they were home and safe, etc.We need to be safe in our houses. See, I got my grandson to put rail locks up. [DKF]

Participants also noted that when they were concerned about others outside the family (such as neighbors), they felt powerless to do much to be effective. This reflected concerns about people stopping doing things they used to do, or being confused regarding time or situations (such as day and night, or days of the week). They did not want to be seen as “interfering” and if they did speak to visiting family, their concerns were often dismissed. When there was no action regarding their concerns, they often felt morally responsible for the person and were sometimes left trying to look after them. While they were generally pleased to do this, it was a cause of stress, and sometimes presented a financial outlay that they could do without.The lady next door who is 88 has […], I think the daughter thinks she’s okay […] I really think she needs help. Whether they’ll do anything about I don’t know. You can only go so far [….] And then we don’t want to be told we’re interfering. I don’t want to think that she’s losing the plot and we’re trying to push her out. How do you deal with these things? [DKG]

Summarizing and synthesizing the findings

We undertook an additional stage of analysis, both to validate our qualitative analysis through triangulation, and to produce a summary in readiness for our planned next stage of Delphi research. From the characteristics identified by participants for successful aging, and the key elements identified of how best to support effective aging-in-place, we distilled a set of consumer-driven priorities that consumers believed could support planning for effective and successful aging-in-place. These priorities were synthesized as an algorithm (HIPFACTS).

- Health: support for self-management, health professionals as needed

- Information services: timely, accessible, online, face to face, one stop

- Practical support: targeted, timely, self-directed, affordable

- Finance: subsidies for those in need

- Activity: physical and mental

- Company: community, family, and pets

- Transport: affordable, reliable, accessible

- Safety: personal, house, and environmental safety and security.

We next mapped the three personal characteristic themes to the eight key elements identified from the interviews (Table 2). This information was reported back to, and checked with, all participants, as a form of participant checking and particularly to recognize our participants as coresearchers.25,26 A letter was sent to participants inviting them to provide feedback and to suggest changes if they did not feel the HIPFACTS algorithm captured an accurate summary of their views. No participants responded to this opt-in invitation. There was general anticipation by the researchers that this set of priorities might assist older people, and their families, to identify emerging support needs and begin to plan for and navigate support services to minimize the negative impact of early FD and continue to successfully age-in-place.

| Table 2 Characteristics of aging well, mapped against key elements of support for successful aging-in-place |

Discussion

This is the first qualitative study, which we know of, to report on consumer perspectives of successful aging-in-place in Australia. Our participant sample was large, and the rigor and generalizability of our findings is enhanced by early data saturation. We believe, from the consistency of information within our first sample, validation of that information from our second independent sample, and subsequent consumer approval of the themes and priorities we generated from the data, that the themes identified are trustworthy and ready for a second phase of development and validation.

Our research provided strong support for the importance of health care providers and policy makers to recognize aging-in-place as the preference of older people who are currently living in the community.21 The responses from our sample reflect the notion expressed by Dollard27 in her PhD thesis, of “comparative optimism”, where the majority of our sample of community-dwelling older people was comparatively optimistic about their chances of aging successfully in their own homes, as long as they had supports that addressed their needs – when and how they needed them- and not generic supports that someone else thought they required. Dollard27 talked about providing positive rather than negative messages to older people about risks associated with adverse events (such as falls), as negative messages may be ignored by older people. She noted in her abstract that “alternative messages should promote [contexts] that are relevant to older people, such as being independent, mobile and active […]”27 The consumers demonstrated a desire to engage with services in this positive manner.

The insights provided by our sample generally support the complex and multisystem changes that were highlighted in the review of diagnostic literature for early FD.12

When participants were asked about successful aging-in-place, they readily described what they and their peers needed to remain living independently in their chosen accommodation. They focused on areas of support that would prevent or minimize the impact of what health literature refers to as FD and talked about adaptation, resilience, and independence. The importance of resilience to people facing a vulnerable phase of their lives, such as older age, is well supported in the social science and psychology literature.28–30 Resilience, as the ability to bounce back following adversity, is a dynamic, complex, and multifaceted process,31 yet our participants reported that this vital prerequisite to successful aging could often be fostered with minimal supports.

Participants were clear that their doctor could only participate in part of their successful journey of aging. They generally went to the doctor with a health problem or issue; they believed that their well-being, safety, and independence was compromised by issues related to anything except health (the H in HIPFACTS); and they would rarely mention this to a primary health provider, as they saw these matters as outside the mandate, interest, or control of their doctor/general practice.

Participants consistently identified the importance of ready access to a central source of service information (the I in HIPFACTS), provided in various forms to suit the end-user needs (ie, internet, in-person, or in printed form) – a starting point for all inquiries and one that did not require money or eligibility criteria. Participants understood and had observed that community support services changed quickly in terms of contact details, type of services provided, costs, eligibility, access, and availability. They were generally realistic about resource limitations but expected, at a minimum, access to accurate and current information so they could make informed decisions – ideally in a proactive way. This sits well with current roles undertaken to various degrees by local councils: making this more consistent and accessible as a first point of call for older citizens would be a practical step in assisting people to take a strengths-based approach to FD, and maintaining resilience, adaptability, and independence with minimum aging-in-place costs to individuals and the broader community.

Reliable provision of timely information and flexible community services – on a fee-for-service basis in some cases – will give taxpayers and the government what they both want: an affordable, community-focused model that values people, their goals, and productivity rather than an expensive, medically focused model that takes over decision-making for people and assumes inevitable decline.

Conclusion

Our qualitative study presents rich, and rarely heard, older people’s views about how they and their peers perceive, characterize, and address changes in their capacity to live independently and safely in the community. Participants identified relatively simple, low-cost, and effective supports to enable them to adapt to change, while retaining independence and resilience. Our analysis resulted in a consumer-informed summary of the characteristics of successful aging and the key elements needed to proactively and efficiently identify, plan for, and support effective aging-in-place.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this paper is a project of the Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute, which is supported by a grant from the Australian Government Department of Health under the Primary Health Care Research, Evaluation and Development Strategy (2013–2015). The information and opinions contained in it do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Australian Government Department of Health.

The research team thanks our research partners, the staff of the Unicare General Practices and at COTA SA, and most importantly, the consumer participants.

The research team also expresses appreciation for the expert advice provided by Professor Jonathan Newbury, Adelaide University; Michael Cousins, chief executive, Health Consumers Alliance SA; and Michael Chalk, CEO, Unicare.

Julie Luker and Kate Kennedy assisted the research team in the preparation and submission of the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):M255–M263. | ||

Grimmer K, Beaton K, Hendry K. Identifying functional decline: a methodological challenge. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2013;4:37–48. | ||

Rockwood K, Howlett SE, MacKnight C, et al. Prevalence, attributes, and outcomes of fitness and frailty in community-dwelling older adults: report from the Canadian study of health and aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(12):1310–1317. | ||

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489–495. | ||

Lipsitz LA. Physiological complexity, aging, and the path to frailty. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2004;2004(16):pe16. | ||

Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, MacKnight C, Rockwood K. The accumulation of deficits with age and possible invariants of aging. Sci World J. 2002;2:1816–1822. | ||

van Haastregt JC, Diederiks JP, van Rossum E, de Witte LP, Crebolder HF. Effects of preventive home visits to elderly people living in the community: systematic review. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):754–758. | ||

Timmer AJ, Unsworth CA, Taylor NF. Rehabilitation interventions with deconditioned older adults following an acute hospital admission: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(11):1078–1086. | ||

Baztán JJ, Gálvez CP, Socorro A. Recovery of functional impairment after acute illness and mortality: one-year follow-up study. Gerontology. 2009;55(3):269–274. | ||

Bynon S, Wilding C, Eyres L. An innovative occupation-focussed service to minimise deconditioning in hospital: challenges and solutions. Aust Occup Ther J. 2007;54(3):225–227. | ||

Ariza-Vega P, Jiménez-Moleón JJ, Kristensen MT. Change of residence and functional status within three months and one year following hip fracture surgery. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(8):685–690. | ||

Beaton K, McEvoy C, Grimmer K. Identifying indicators of early functional decline in community-dwelling older people: a review. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15(2):133–140. | ||

Vasunilashorn S, Steinman B, Liebig P, Pynoos J. Aging in place: evolution of a research topic whose time has come. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:120952. | ||

Chiu E. Ageing in place in Hong Kong – challenges and opportunities in a capitalist Chinese city. Ageing Int. 2008;32:167–182. | ||

Gray M, Heinsch M. Ageing in Australia and the increased need for care. Ageing Int. 2009;34(3):102–118. | ||

Johansson K, Josephsson S, Lilja M. Creating possibilities for action in the presence of environmental barriers in the process of ageing in place. Ageing Soc. 2009;29(1):49–70. | ||

Lai O. The enigma of Japanese ageing-in-place practice in the information age: does digital gadget help the (good) practice for inter-generation care? Ageing Int. 2008;32:236–255. | ||

Sixsmith A, Sixsmith J. Ageing in place in the United Kingdom. Ageing Int. 2008;32:219–235. | ||

Gibson D, Rowland F, Braun P, Angus P. Ageing in place: before and after the 1997 aged care reforms. 2002; AIHW Bulletin number 1. Cat. number AUS 26. Canberra, Australia: AIHW. Available from: http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442467355. Accessed August 4, 2015. | ||

American Association of Retired Persons (AARP). Understanding Senior Housing: Into the Next Century. Washinton, DC: AARP; 2003. | ||

Olsberg D, Winters M, Housing A. Ageing in Place: Intergenerational and Intrafamilial Housing Transfers and Shifts in Later Life. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, UNSW-UWS Research Centre; 2005. | ||

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population Projections, Australia (No 3222.0). Canberra, ACT2012. | ||

Nourhashémi F, Andrieu S, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Vellas B, Albarede JL, Grandjean H. Instrumental activities of daily living as a potential marker of frailty a study of 7364 community-dwelling elderly women (the EPIDOS study). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(7):M448–M453. | ||

Hwang E. Exploring aging-in-place among Chinese and Korean seniors in British Columbia, Canada. Ageing Int. 2008;32:205–218. | ||

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Meth. 2006;18(1):59–82. | ||

Berg BL, Lune H. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. 8th ed. Essex, UK: Pearson Education Ltd; 2011. | ||

Dollard J. Comparative optimism about falling amongst community-dwelling older South Australians: a mixed methods approach. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. School of Population Health and Clinical Practice, University of Adelaide; 2009. | ||

Bowling A, Iliffe S. Psychological approach to successful ageing predicts future quality of life in older adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9(1):13–23. | ||

van Kessel G. The ability of older people to overcome adversity: a review of the resilience concept. Geriatr Nurs. 2013;34(2):122–127. | ||

Wiles JL, Wild K, Kerse N, Allen RE. Resilience from the point of view of older people: “There’s still life beyond a funny knee.” Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(3):416–424. | ||

Windle G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2011;21(2):152–169. |

Supplementary material

Interview guide

- What would you say are the most important areas for action to enable older people to retain the right to live in the community home of their choice?

- Can you think of a group of older people in the community who are now older and whom you have known over many years – it could be family, a work or social group.

- Have you observed if any of them are not able to do what they used to do previously?

- If yes, what sorts of things do they no longer do that they might want to do?

- Why?

- What might help them to still do what they want to do?

- Why isn’t this happening?

- Is it the same for all members of the group?

- Why? What makes the difference?

- Do you have any personal perspectives on this?

- What should the community (local councils and government) do to make it easier for older people to continue to live where they want to live in the community?

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.