Back to Journals » Open Access Journal of Contraception » Volume 6

Five-year review of copper T intrauterine device use at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar

Authors Iklaki C, Agbakwuru A, Udo AE, Abeshi SE

Received 4 February 2015

Accepted for publication 13 May 2015

Published 5 October 2015 Volume 2015:6 Pages 143—147

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJC.S82176

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Igal Wolman

Christopher U Iklaki, Anthony U Agbakwuru, Atim E Udo, Sylvester E Abeshi

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria

Background: The intrauterine devices (IUDs) are widely used contraceptive methods all over the world today. They are effective and recommended for use up to 10 years. They are not without side effects, which often prompt the users to request for removal.

Objective: To determine the utilization rate of copper T intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD), side effects, and request for removal at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar.

Methods: The data on usage of the various forms of temporary contraception provided by the Family Planning Clinic of this center from January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2010 were collated. The records of usage of IUCD during same period were carefully studied.

Results: During this period, a total of 10,880 users were provided with various forms of contraceptives. Copper T IUD was the commonest form of contraception used at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital Family Planning Unit over the period under review (2006–2010) with a rate of 4,069 (37.40%). There was a yearly higher request for IUCD over other forms of contraceptives over the period. Of a total of 4,069 users of the copper T IUD method over the period, 1,410 (34.65%) belonged to the age group of 25–29 years. Eleven (4.61%) of the users requested for its removal due to abnormal vaginal bleeding, while five (2.08%) removed theirs due to abnormal vaginal discharge. The major reason for removal was the desire for pregnancy that accounted for 165 (70.26%), while one (0.51%) was removed due to dysmenorrhea.

Conclusion: The copper T380A was very effective, safe with fewer side effects, and easily available in this study. The request for removal is also low in our environment.

Keywords: copper T380A, contraception, request for removal

Introduction

One of the most sensitive and intimate decisions made by an individual or by a couple is that of fertility control.1,2 This decision is often based on deeply held religious or philosophical convictions. Thus, the clinician must approach the patient’s fertility needs with particular sensitivity, empathy, maturity, and nonjudgmental attitude.1 Many couple use contraception to space their children or to limit the size of their family. Others desire to avoid childbearing because of the effects of pre-existing illness on the pregnancy, such as severe diabetes, or heart disease.1–4 As a matter of public policy, some countries, especially those that are less developed, promote contraception in an effort to curb undesired population growth.5,6

This cross-sectional study was carried out at the Family Planning Unit of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital (UCTH), Calabar, Nigeria. UCTH is a tertiary health facility located in Calabar, south–south geopolitical area of Nigeria and provides tertiary health care services for about three million people. The Family Planning Unit is run by doctors, nurses, and other health care workers in the department. Several methods of contraception such as implants, injectables, pills, and intrauterine devices (IUDs) are offered here. IUDs are cheap and affordable and usually preferred by our client.

Health care providers usually provide all persons requesting contraception with detailed information about the use of the method or methods, benefits, risks, and side effects so that an informed choice can be made relative to a particular method.7 Different methods of contraception are therefore in use today,2,7–13 and each has over time been undergoing developments toward achieving the above goals.

The IUDs are among the most widely used contraceptive methods. The copper IUDs are very effective and licensed to last 3–10 years. These devices, although effective, are not without side effects, which often prompt the users to request for removal.14–16 It has undergone a lot of development, from the first generation of nonmedicated devices dominant in the 1960s. The first-generation devices include the Lippes loop and Saf-T coil made of plastic, the M-device and the Y-device made of stainless steel, the Dalkon shield made of polyvinyl acetate, the copper 7 (Gravigard) and copper-T 200. The second-generation medicated IUDs of the 1970s and 1980s had primarily copper added to them. The second-generation IUDs include the Nova-T (Noncard) and multiload 250. The basic difference in the copper devices is in the shape and the amount of copper.1–10 The third-generation IUDs commonly in use now include copper T380A, 380S, 380Ag, multiload 375, copper-safe 300 (Cu-safe 300), copper Fix 330 or Flexigard 330 and levonorgestrel releasing IUD (Levonal).6,13

The third-generation IUDs are improvement on the second-generation devices, and some are impregnated with progestogen.9–11 Recently, an intrauterine system containing levonorgestrel (released at 20 μg/day; Mirena) has been approved for use. It provides contraception for up to 5 years. The third-generation IUDs have been developed to reduce some of the common side effects related to IUD use as well as combine the benefits of IUD and hormonal contraception in other cases. Some of these devices have design modifications to reduce the incidence of pain, spontaneous expulsion, and bleeding.13

Copper T380A is by far the most popular IUD in the world, and it is the device used commonly in UCTH among other methods. It is introduced into the endometrial cavity through the cervical canal. A large variety of shapes and sizes have been tried with varying degrees of contraceptive effectiveness.6,7,18–22 The paragard (copper T380A) is wound with copper wire that creates a surface area of copper 300 mm2 on the vertical arms and 40 mm2 on each of the transverse arms; the lifespan of this device is at least 10 years.23

The exact mechanism of action is unknown. Current theories include spermicidal activity, interference with either normal development of ova or the fertilization of ova, and activity of the endometrium that may promote phagocytosis of sperm and also may impede sperm migration or capacitance. The most widely observed phenomenon is mobilization of leukocytes in response to the presence of the foreign body. The leukocytes aggregate around the IUD in the endometrial fluids and mucosa and, to a lesser extent, in the stroma and underlying myometrium. It is hypothesized that the leukocytes produce an environment hostile to the fertilized ovum.20,23 Efficacy with the copper T380A device is high, with a failure rate of less than 1% per year with prolonged use.19,23

The side effects of bleeding, pelvic infection, and pain are common reasons for removal of the method of contraception. Medical reasons for removal are partial expulsion, usually occurring in the first few months of use, persistent cramping, bleeding or anemia, accounting for about 20% of removals during the first 3 months, acute salpingitis, or Actinomyces on Pap smear, pregnancy, intra-abdominal placement or perforation; and significant post-insertion pain, which may indicate improper placement or partial perforation.14 As is the case with expulsion, the incidence of pain or bleeding is more or less proportional to the degree of endometrial compression and myometrial distention brought about by the IUD.22 The highest risk of pelvic infection associated with the use of IUD (three- or four-fold increase) occurs around the time of insertion, suggesting that endometrial cavity contamination is a major mechanism.5

There are absolute contraindications to IUD use, these include current pregnancy, undiagnosed abnormal vaginal bleeding, acute pelvic inflammatory diseases, and suspected gynecologic malignancy.15,17,23

It is therefore necessary to determine the complications and reasons for removal and side effects of copper T intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD) and to find ways to improve on the utilization. This study is aimed to determine the utilization rate of copper T IUCD, side effects, and request for removal at UCTH, Calabar.

Study area and setting

This retrospective study was carried out in Calabar, the capital city of Cross River State, Nigeria. It is made up of two local government areas and 22 geopolitical wards. The total population for this area is 418,652 with majority of the workforce being in government employment or involved in small-scale business ventures. The area hosts a Teaching Hospital, one General Hospital, several maternal and child health centers, and several private hospitals. The Family Planning Clinic of the UCTH, Calabar, keeps meticulous records of women who are reviewed regularly. At the first visit, women are counseled, and a detailed gynecological/medical history is taken. Pregnancy and contraindications to safe contraceptive use are excluded. Relevant investigations requested for by the attending doctor/nurse are as indicated. Following counseling sessions, clients who accept copper T are fitted with the device. Clients are followed up after 1 and 3 months, then yearly according to the clinic protocol. A woman was considered lost to follow-up if after 12 months she had not reported for her next appointment. Cumulative cost of service over a 5-year period is cheapest for copper-T $5 (at current exchange rate of $1 to  200) compared with vasectomy ($10), implants ($11), injectables ($12), oral contraceptives ($15), condoms ($19), and tubal sterilization ($28).

200) compared with vasectomy ($10), implants ($11), injectables ($12), oral contraceptives ($15), condoms ($19), and tubal sterilization ($28).

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective study. Approval was obtained from the Ethics committee and guidelines for retrospective studies followed. The data of users of copper T IUCD provided by the Family Planning Clinic of this center from January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2010 were collated from the patient record folders. The records of users of other various forms of contraceptives during same period were also obtained. Other parameters of the IUCD users’ reviewed were their age distributions, parity, level of education, and reasons for removal. All clients lost to follow-up were excluded from the study. The results obtained were analyzed using simple percentages and ratios. Statistical software (Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Georgia, USA) was used for data analysis.

Results

During this period, a total of 10,880 users were provided with various forms of contraceptives.

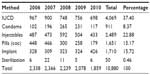

Table 1 shows the yearly distribution of various forms of contraceptives over the study period.

Copper T IUCD was the commonest form of contraception used at the UCTH Family Planning Unit over the period under review (2006–2010) with a rate of 4,069 (37.40%). There was a yearly higher request for IUD over other forms of contraceptives over the period. However, the yearly demand for IUCD usage declined from 43.25% in 2006 to 40.07% in 2010. This may be attributed to the increase usage of implants over the period of study.

Table 2 shows the age distribution of copper T contraceptives over the study period.

| Table 2 The age distribution of copper T IUCD users over the period reviewed |

Of a total of 4,069 users of the IUD method over the period, highest users accounting for 1,410 (34.65%) belonged to the age group of 25–29 years. There was a corresponding decrease in request for the method with age, accounting for six (0.14%) at age 50 and above.

Out of a total of 4,069 users of the IUD method over the period, para 4–5 were the highest users accounting for 2,561 (62.9%), while para 0–1 were least 73 (1.8%). No nulliparous women used the method over the study period, and 4,031 (99.1%) of the women were married. The mean parity was 4.2±2.6.

A total of 240 (5.9%) had no formal education, 367 (9.0%) had primary education, 2,198 (54.0%) of the patients had secondary education, and 1,264 (31.1%) had tertiary education. Users of copper T IUD were highest among women with secondary education. Lack of formal education was associated with lowest rate of utilization of the contraceptive method.

Table 3 shows the indications for removal of IUD by users during the period under review.

| Table 3 The indications for removal of IUCD by users during the period under review |

IUCD seemed a highly preferred method of contraception as only eleven (4.61%) and five (2.08%) of the users requested for reversal due to abnormal vaginal bleeding and abnormal vaginal discharge, respectively. The major reason for removal was the desire for pregnancy that accounted for 165 (70.26%), while one (0.51%) was removed due to dysmenorrhea. The method was an effective mode of contraception as only one (0.51%) method failure was recorded.

There were 4,069 users of the IUD over the study period; 235 (5.8%) requested for removal of the device for several reasons.

Discussion

Contraceptive prevalence in Nigeria, representing the percentage of couples in the reproductive age group using modern contraception, is about 6% compared with over 50% worldwide.6,7 A total of 10,880 users were provided with various forms of contraceptives during the period under review (2006–2010) in this center. Copper T IUD was the commonest form of contraception used at the UCTH Family Planning Unit with a rate of 4,069 (37.40%). There was a yearly higher request for IUD over other forms of contraceptives. This is similar to a finding in Jos by Mutihir et al8 and in Enugu by Oguanuo et al.9 However, a study in Zaria10 revealed that injectable (Depo-Provera and Noristerat) contraceptives was mostly utilized.

There was an increased demand for various forms of contraception, especially during the peak of reproductive ages of 25–39 years with the highest demand of 2,824 (25.96%) noticed among the group of 30–34 years similar to the finding in Sokoto.11 The finding may be because this is the age at which most individuals aspire to attain the peak in their career, hence the request for contraception so as not be hindered by unwanted pregnancies.

Parity distribution of copper T contraceptives users in this study shows that para 4–5 were the highest users accounting for 2,561 (62.9%) with mean parity of 4.2±2.6 similar to a study in Jos.8 The finding may be due to the practice of restricting copper T intrauterine contraceptives use for multiparous women and couples in mutually monogamous relationship to reduce the risk of pelvic inflammatory diseases.23,24 In our center, nulliparous women and those who are not in a monogamous relationship are advised against the use of IUD.

Users of copper T IUD were highest among women with secondary education. Lack of formal education was associated with lowest rate of utilization of the contraceptive method. The findings are similar to a study in Zaria10 and findings from the 2003 National Health and Demographic Survey.12,24

The commonest request for removal, however, is the desire to get pregnant. This accounted for 70.26% of the total request for removal in this study. This is similar to a study in Jos where desire to get pregnant was commonest accounting for 31.9%.8

This was followed by removal and re-insertion following expiration of the period of usage, accounting for 11.23%. Only 235 (5.80%) of those using the copper T requested for removal over the period of study. This may be because many of them are lost to follow-up considering the long period of usage. Majority of the women would have relocated to other areas or even removed them in other facilities. Other cases necessitating removal of the copper T device were abnormal vaginal bleeding (4.61%), abnormal vaginal discharge (2.08%), lower abdominal pains (2.08%), and new spouse (1.13%). However, the reduction in other problems related to the use of currently available IUDs, namely expulsion, bleeding, and pain, has been less impressive.13 Advances in IUD technology have led to the development of highly effective, safer, and long-lasting devices.13 The original IUDs are obsolete as they were associated with menorrhagia and severe dysmenorrhea, for example, Lippes loop and Saf-T coil, or increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease, for example, Dalkon shield.13,14 Attention currently is on Flexigard 330 (CuFix 330), which has significantly less removal for pain and bleeding. It has a polylactide biodegradable anchor, which imbeds in the uterine muscle making it suitable for postpartum insertion.13,14 Other IUDs that have been designed to reduce expulsion and minimize necessity of removal due to pain and bleeding are Cu-safe 300, Ombrelle 250 (organon), copper T188, and Shanghai V-200.6

Contraceptives occasionally fail. Failure rates are described by the Pearl Index, which refers to the number of failures per 100 women using the contraceptive method for a year (100 women years). The copper T380A has a first-year failure rate of 0.4 per 100 women; a 5-year failure rate of 1.3 per 100 women.18 The copper T380A has an average annual pregnancy rate of approximately 0.3 per 100 women years over a 10-year period.6,14 A failure rate of one (0.51%) was noted over a 5-year period in this study. The low failure rate may also be due to lost to follow-up. The patients also agreed that there was a reduction in side effects such as bleeding and pain.15,19

Conclusion

The awareness and willingness to use modern contraceptive to control family size and prevent unwanted pregnancies are on the increase.

The copper T380A is very effective, safe, long-acting, easily available, and the most immensely used method of birth control in this study. Abnormal vaginal bleeding associated with copper T380A was a major side effect responsible for its removal. Effort should therefore be made to make available in all centers other forms of IUCDs with minimal side effect to improve utilization.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Mishell DR. Contraception, sterilisation and pregnancy termination. In: Stenchever MA, Droegemueller W, Herbst AL, Mishell Jr DR, editors. Comprehensive Gynaecology. Vol 4. St Louis: Mosby Inc.; 2001:295–353. | |

Nnatu S. Female sterilization techniques. Update. J Obstet Gynaecol East Cent Africa. 1984;4:187–191. | |

Arkutu A. Family planning in sub-Saharan Africa: present status and future strategies. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1995;50(Suppl 2):27–34. | |

Guillebank JD, Souza R. Contraception past, present and future. In: O’Brien PMS, editor. The Year Book of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. London: RCOG Press; 2000:255–269. | |

Akinkugbe A. Fertility regulation; contraception, family planning. A Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1st ed. Akinkugbe A. editor. Evans Brothers (Nigeria) Ltd; 1996:435–462. | |

Clerk NT, Ladipo OA. Contraception. In: Agboola A, editor. Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology for Medical Students. Vol 2. Ibadan: Heinemann Educational Books; 2006:145–154. | |

Sheaman RP. Contraception and sterilization. In: Whitfield CR, Dewhurst J, editors. Dewhurst’s Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology for Postgraduates. Vol 36. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1995:539–549. | |

Mutihir JT, Iranloye T, Uduagbgbamen PFK. How long do women use the intrauterine device in Jos Nigeria? J Med Trop. 2005;7(2):13–19. | |

Oguanuo TC, Anolue FC, Ezegwui HU. Norplant contraception in the University Of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Enugu: a six year review. J Coll Med. 2001;6(2):94–97. | |

Ameh N, Sule ST. Contraceptive choices among women in Zaria, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2007;10(3):205–207. | |

Ibrahim MT, Sadiq AU. Knowledge, attitude, practices and beliefs about family planning among women attending primary health care clinics in Sokoto, Nigeria. Niger J Med. 1999;8:154–158. | |

Family Planning in Nigeria. Demographic and Health Survey. Cleveland (MD): National Population Commission and Orc Macro; 2004:61–81. Available from: https://www.google.co.nz/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0CB0QFjAAahUKEwirxZ6t88DHAhVFF5QKHXlkCck&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.dhsprogram.com%2Fpubs%2Fpdf%2FFR148%2FFR148.pdf&ei=HaDaVevCFMWu0AT5yKXIDA&usg=AFQjCNH6QmV0uqbyD0Fz4lg3PinpaDYJKg&sig2=zkMgm47MXyGI8tnMdukopQ. | |

Reinprayoon D. Advances in intrauterine device technology. In: Hedon B, Bringer J, Mares P, editors. Fertility and Sterility. A Current Overview. London: Parthenon Publishing Group; 1995:31–33. | |

Burkman RT. The relationship of genital tract Actinomycetes and the development of pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;143:585.s | |

Burkman RT. Association between intrauterine device and pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;57(3):269–276. | |

Sivin I, Tatum, HJ. Four year’s experiences with the Tcu 380Ag intrauterine contraception device. Fertil Steril. 1981;36:159. | |

Tatum HJ, Connell EB. A decade of intrauterine contraception: 1976 to 1986. Fertil Steril. 1986;46:173. | |

Zinger M, Thomas, MA. Using the levonorgestrel intra-uterine system. Contemp Ob Gyn. 2001;46(5):35–48. | |

Sivin I, Stern J. Health during prolonged use of levonorgestrel 20 micrograms/d and the copper TCu 380Ag intrauterine contraceptive devices: a multicenter study. International Committee for Contraception Research (ICCR). Fertil Steril. 1994;61(1):70–77. | |

Van Os WAA. Intra-uterine devices. In: Studd J, editor. Progress in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Vol 3. 3rd ed. London: Churchill-Livingstone; 1983:294–296. | |

Farr G. New development in intrauterine devices. Netw Res Triangle Park N C. 1991;12(2):9. | |

Coutinho EM, Hanson de Moura L. New leads in contraceptive research. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;11(1):36–40. | |

Ronald T, Burkman RT. Contraception and family planning. In: DeCherney A, Nathan L, Goodwin TM, Laufer N, editors. Current Diagnosis and Treatment Obstetrics and Gynecology. 10th ed. London: Lange Medical Book/McGraw-Hill; 2007:579–596. | |

Iklaki CU, Ekabua JE, Abasiattai A, Bassey EA, Itam HI. Spousal communication in contraceptive decisions among antenatal patients in Calabar, South Eastern Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2005;14(4):405–407. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.