Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 14

Feeling Trusted or Feeling Used? The Relationship Between Perceived Leader Trust, Reciprocation Wariness, and Proactive Behavior

Authors Ye S, Xiao Y, Wu S, Wu L

Received 8 July 2021

Accepted for publication 9 September 2021

Published 22 September 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 1461—1472

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S328458

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Suyang Ye, Yunchun Xiao, Shuang Wu, Lixia Wu

School of Business Administration, Zhejiang Gongshang University, Hangzhou, 310018, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Yunchun Xiao Email [email protected]

Purpose: The prevailing literature on perceived leader trust has focused on its benefits on employees’ work behavior. However, recent researches suggest that the feeling of leader trust also brings strains and work overload. Thus, existing researches have not yielded consistent conclusions about how the “trusted” employees tend to behave after being trusted by their leaders. Integrating the trait activation theory and self-evaluation psychological states, this study develops and tests the double-edged effects of perceived leader trust on proactive behavior through the different mediating roles of employee’s psychological variables. Specifically, we argued that the perceived leader trust effect is dependent on the employee’s reciprocation wariness, which to a large extent determines employees’ response to the perceived leader trust (ie, sense of self-worth and role overload).

Methods: The study uses a systematic literature review to identify the arguments supporting the relationship between the constructs and propose model. Additionally, this study adopts the multi-source design approach and collects data in a large Housing Construction & Development Company, which comprised 372 valid samples. Besides, hierarchical regression and bootstrapping methods are also employed to test the hypotheses.

Results: This study reveals that employee’s reciprocation wariness is negatively moderated the relationship between perceived trust and sense of self-worth while positively moderated the relationship between perceived trust and sense of role overload. Moreover, the higher the employee’s reciprocation wariness, the more negative the influence of perceived trust will be on the employee’s proactive behavior via the sense of role overload; on the contrary, the lower the employee’s reciprocation wariness, the more positive the influence of perceived trust will be on the employee’s proactive behavior via the sense of self-worth.

Conclusion: This study examines the double-edged sword influence of perceived leader trust on employee behavior. It found that perceived leader trust will affect proactive behavior through employees’ subjective evaluation of the leader’s trust. Moreover, employee’s reciprocation wariness plays a moderating role in this relationship. In a word, this paper deeply analyzes the mechanism and boundary conditions of perceived leader trust influencing employees’ psychological state and behavior, contributing to organizational trust and workplace proactive behavior research.

Keywords: perceived leader trust, sense of self-worth, sense of role overload, proactive behavior, reciprocation wariness

Introduction

Proactive behavior refers to the work behavior that individuals actively change rather than passively adapt from a long-term perspective.1 It is evident that proactive behavior is an important contributor to positive outcomes such as firm performance and firm competitiveness.2 Thus, how to increase proactive behavior has gradually become the focus of business and academic circles.3 Previous studies have pointed out that feeling trust will facilitate employee’s proactive behavior via positive cognitive-motivational states.4,5 For example, employees perceiving trust are considered to be able to increase their commitment to the organization, gain confidence in their own abilities, enhance their control strength, and feel more likely to “take the risk”.4,6–8 Therefore, scholars call on organizations to create a working atmosphere full of trust to enhance employees’ proactive behavior.9,10

However, recently, some scholars have suggested that there may be possible “dark sides” of perceived leader trust.11,12 Perceived trust is different from trust. The reference object of trust is the principal, and the reference object of perceived trust is the trustee.13 Perceived trust means that the trustee perceives that the others trust himself. Even if the others do not trust himself/herself in their heart, the trustee can still feel the others’ trust in himself/herself from their behavior.14 Skinner et al15 showed that perceived trusted by leader means taking on more additional responsibilities to the original role of employees. Specifically, interpersonal trust draws the trusted recipient into an uncomfortable exchange dilemma. Chen et al11 found that perceived trust may bring bad effects such as emotional exhaustion and strains, thus induce employees’ subsequent counterproductive work behavior. How employees view being trusted by their leaders depends on their interpretation of leader’s trust.12,16 In this paper, we extend Baer et al12 findings and suggest that perceived leader trust may have both positive and negative influences on employee’s proactive behavior.

Integrating the trait activation theory, we explore how and when perceived leader trust may lead to positive and negative effects in employee’s proactive behavior. The trait activation theory framework notes that individual traits will interact organically with organizational situations in work surroundings, thus prompting individuals to show different behavioral responses.17 Building on this theory, we posit that perceived leader trust could lead to a different level of employee’s proactive behaviors, which depends on how individual trait affect their interpretation of leader’s trust. On the one hand, employees perceiving leader trust will think that their leader recognizes them, and their self-esteem will be satisfied. In return for the trust of their leader, they will complete their own tasks more actively;6 On the other hand, employees perceiving leader trust may have certain psychological pressure, because the trust and reliance of the leader means giving employees more tasks and consuming their self-energy.14 In fact, both the positive and the negative psychological impact brought by perceived leader trust jointly show the psychological panorama of employees perceiving trust.12 Therefore, it is necessary to integrate two different employee reactions in the research, to further clarify the mechanism of employees’ perceived leader trust on proactive behavior.

We further propose that sense of self-worth and sense of role overload as mediation mechanism, both of which belong to individual psychological variables and are subjective perceptions produced after individual cognitive evaluation. Sense of self-worth is an individual’s subjective feeling after evaluating himself, that is, “human” subjective evaluation,18 and sense of role overload is an individual’s subjective feeling after evaluating his work, that is, “work situation” subjective evaluation.19 In other words, perceived trust may stimulate employees’ positive self-evaluation, and also can cause employees’ negative evaluation of sense of role overload. Therefore, this paper starts from employees’ evaluation perception of trust and discusses how employees’ perception of trust affects proactive behavior through sense of self-worth and job sense of role overload, and clarifies the whole picture of employees’ behavior with perceived trust.

In addition, if the two perceptions of being trusted are regarded as employees’ psychological states of being trusted, when are employees more inclined to stimulate their sense of self-worth and when are they more inclined to trigger their sense of role overload? At present, it is not clear under what circumstances employees who perceive to be trusted will participate in what kind of trusted evaluation process. This paper introduces reciprocation wariness, an important evaluation predictive factor,20 to investigate how employees choose evaluation mechanism and produce different psychological perception when they feel trusted by the leader. Furthermore, for employees with high reciprocation wariness, perceived trust reduces proactive behavior by producing a sense of role overload; For employees with low reciprocation wariness, perceived trust increases proactive behavior by improving their sense of self-worth.

This study makes several theoretical contributions to this field. First, we extend research on the dark side of perceived leader trust and provide initial evidence for the negative consequences of perceived leader trust on employee’s proactive behavior. Our paper provides empirical evidence for the double-edged effects of perceived leader trust on employees’ follow-up proactive behavior. Second, using two psychological evaluation processes, specifically, sense of self-worth and sense of role overload, as a manifestation of the trait activation theory, we contribute to the trait activation theory by operationalizing the mechanism of when the trustee falls into what psychological evaluation processes. Finally, we identify employee’s reciprocation wariness as key contingencies affecting the proposed double-edged effects of perceived leader trust through psychological evaluation processes. Our results will make it easier to predict which employees are more likely to generate proactive behavior when perceived leader trust.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Influence of Perceived Trust and Reciprocation Wariness on Sense of Self-Worth

Reciprocation wariness refers to the individual tendency to worry about being used by others in social exchange relations.20 In the context of the workplace, reciprocation wariness often indicates the employee’s tendency to worry about being used by the leader during interaction with them. The core of social exchange is often closely correlated with the principle of reciprocity, which means that people who are favored by others have the obligation to repay others in a certain way.21 Previous studies show that individuals have different levels of reciprocation wariness in social exchanges: employees with high reciprocation wariness tend to think that others are treating them well with some potential purpose, rather than sincerely doing so.22 Therefore, when they perceive the leader’s trust, employees with high reciprocation wariness are more likely to interpret it as a purposeful attempt. For fear of being used by the leader, these employees will respond negatively or reduce their reward behaviors. On the contrary, employees with low reciprocation wariness are not worried about being used.20 They tend to understand leader’s trust on them as a form of recognition and affirmation, and are therefore more willing to actively repay the trust of the leader owing to the reciprocal psychology.

The sense of self-worth refers to an individual’s comprehensive evaluation of himself. The evaluation and acceptance of others is an important source of the sense of self-worth.18 Previous studies have shown that the perceived trust is an important way for employees to perceive the sense of self-worth in organizations. For example, Parker et al4 believed that perceived trust of the leader can increase employees’ positive evaluation of themselves. According to the Trait Activation Theory, perceived leader trust is an organizational context and reciprocation wariness is a personality trait of employees, and the latter often affects employees’ evaluation and reward of the former. Specifically, for fear of being used in interpersonal relationships, employees with high reciprocation wariness will reduce their gratitude to their leader while reducing their work engagement.22 Employees with high reciprocation wariness are more likely to evaluate perceived trust as purposeful behavior of their leader. These employees tend to consider the leader trust as the foreshadowing of more responsibilities and obligations to be imposed on them, and will therefore not experience an increase of self-worth. However, employees with low reciprocation wariness tend to evaluate perceived trust as their leader’s genuine kindness. They believe it is the affirmation and recognition of themselves, which will enhance their own positive evaluation and generate a higher sense of self-worth. Based on the above analysis, this paper argues that for employees with low reciprocation wariness, perceived leader trust will lead to an increase of their sense of self-worth; However, for employees with high reciprocation wariness, perceived leader trust will not lead to an increase of their sense of self-worth. As such, we propose:

Hypothesis 1: Reciprocation wariness moderates the relationship between perceived trust and sense of self-worth, such that the relationship is positive and stronger when employee’s reciprocation wariness is low (rather than high).

Influences of Perceived Trust and Reciprocation Wariness on Sense of Role Overload

There are three definitions of the sense of role overload based on three different perspectives, namely, the time perspectives, the resources perspective, and the integration of both. From the time perspective, the sense of role overload refers to too many demands and too much work pressure within too limited period of time;23 From the perspective of resources, the sense of role overload happens on employees who lack sufficient personal resources but undertake too complex and difficult tasks.24 From the perspective of the integration of time and resources, the sense of role overload indicates the role pressure perceived by employees who take on too many tasks and responsibilities under the condition of limited available time and resources.25 This paper chooses the third definition which combines the perspectives of time and resources to define employees’ sense of role overload. This is because perceived trust always accompany with the feeling of more role expectation from the leader, which will potentially lead employees to take on more challenging roles with limited time and resources while generating more stressful feeling in employees. Therefore, the sense of role overload is a subjective feeling when the role expectation (job requirement) exceeds the employee’s available time and self-ability (resources).

The perceived leader trust is usually conveyed by the leader through the assignment of more tasks and the implication of higher expectations to the employees. This kind of leader trust will increase employees’ pressure12 and lead to employees’ emotional exhaustion.13 On the one hand, perceived trust and dependence from the leader will increase employees’ role expectations and tasks. When employees feel weakness and burnout due to the increase of workload and work difficulty,26 their sense of role overload will occur. On the other hand, the leader’s trust means that the leader will share more information with employees.27 Although the information sharing by the leader will not lead to a direct increase in tasks and responsibilities, it often means a multi-faceted expectation for employees, which may lead to the increase of employees’ sense of responsibility and the expansion of their role scope.6 In a word, the leader’s trust will increase extra-role expectations for employees, and when this expectation exceeds the time and ability range of employees, it will cause role overload of employees. Based on the Trait Activation Theory, employees with high reciprocation wariness tend to think that the leader’s trust indicates the leader’s attempt of utilizing them to solve his own problems. Therefore, when perceiving the leader’s trust, they may doubt the leader’s motivation and worry that the leader will use themselves for his own interests, for which reason they may evaluate the leader’s trust as a purposeful act.20 At this time, employees who are unable to take on additional workload and yet are afraid to refuse their leaders’ expectations will experience a higher sense of role overload. However, employees with low reciprocation wariness are more likely to evaluate the leader’s trust as a positive event, and to recognize the affirmation and recognition of the leader as a beneficial organizational resource for themselves, thus leading to the reduction of their sense of role overload.28 Therefore, Therefore, in the confrontation of the leader’s trust, employees with high reciprocation wariness may perceive more sense of role overload, while employees with low reciprocation wariness may perceive less sense of role overload. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 2: Reciprocation wariness moderates the relationship between perceived trust and sense of role overload, such the relationship between them is positive and stronger when reciprocation wariness is high (rather than low).

A Moderated-Mediated Model

Proactive behavior refers to the behavior in which employees actively overcome difficulties and obstacles to complete tasks and achieve established goals. Proactive behavior is featured by three characteristics, namely, spontaneity, forward-looking, and the strength to overcome difficulties.29 Spontaneity means that employees will spontaneously and proactively complete tasks inside and outside the scope of employees’ job responsibilities even if no tasks have been assigned by the leader; Forward-looking refers to the tendency to consider problems from a long-term perspective and make preparations in advance so that when the problems do occur, they will be dealt with quickly and smoothly; The strength to overcome difficulties means that when encountering difficulties, the employees can be self-driven and courageous enough to accept challenges overcome the obstacles. The resources owned by employees will affect their proactive behaviors. The resources owned by employees will affect their proactive behaviors.30 As an important individual resource, the sense of self-worth is an essential factor that may affect employees’ initiative and proactive behavior. Previous studies have also shown that employees with a high sense of self-worth will engage in more proactive behavior.31 On the contrary, when employees perceive a higher sense of role overload, their available time and resources will decrease, which will reduce employees’ ability to control their work and lead to their reduced proactive behavior.32

Accordingly, this paper has put forward the moderating effect of reciprocation wariness on perceived leader trust and the sense of self-worth (Hypothesis 1), the moderating effect of reciprocation wariness on perceived leader trust and the sense of role overload (Hypothesis 2), and the influence of sense of the self-worth and the sense of role overload on proactive behavior, respectively. Based on the above hypotheses, this paper further proposes a moderated mediation model. To be specific, the influence of perceived leader trust on proactive behavior is dependent on how employees evaluate the leader’s trust. Employees with high reciprocation wariness are more likely to regard the leader’s trust as a tool of the leader to press more workload on employees, thus having fewer willingness to reciprocate the trust of their leaders, showing less sense of self-worth and more sense of role overload; On the contrary, employees with low reciprocation wariness are more likely to regard leader’s trust as a kind of recognition and dependence of the leader on themselves, as well as an important organizational resource, thus feeling more willingly to work hard to repay the trust of the leader, more sense of self-worth and less sense of role overload. Therefore, we continue to propose the following hypotheses (Figure 1 summarizes our overall theoretical model):

Hypothesis 3a: perceived leader trust is more positively related to employee’s proactive behavior via the sense of self-worth when an employee’s reciprocation wariness is lower. Hypothesis 3b: perceived leader trust is more negatively related to employee’s proactive behavior via the sense of role overload when an employee’s reciprocation wariness is higher.

|

Figure 1 The hypothesized model. |

Method

Sample and Procedure

We collected data from a large housing Construction & Development company located in the southern of China. The major businesses of this company are housing, transportation, roads and bridges construction. It is one of the top 50 private enterprises in China. According to our preliminary interviews, this sample is particularly suitable for testing our research model for several reasons. First, this working surrounding requires a lot of interpersonal interactions. Factory workers always work closely with their supervisors, providing an excellent context for studying perceived leader trust and employee’s proactive behavior. Second, factory workers had personal agendas, such as behavior outstanding in teams and achieving individual awards and promotions. Thus, those workers might choose how to repay the trust of the leader, depending on their reciprocation wariness.

In order to reduce the concerns about common method bias, we adopt a multi-source design to collect data.33 Specifically, we collect data from both employees and their direct leaders. The survey was supported by the company’s chief executive, and the HR manager provided the roster of the surveyed employees’ names and their direct leaders’ names for this study. In this study, two waves of data were collected, with an interval of 2 months. We used the employee’s work IDs and names to match the two-wave responses. Each employee and his/her leader were investigated via a sealed paper questionnaire to guarantee confidentiality. Eighty-six team leaders with a total of 534 subordinates completed all surveys. The average number of subordinates rated by the leader is 6.1.

At time point 1, employees were asked to self-evaluation on perceived trust and reciprocation wariness, where 497 questionnaires were collected, and 456 questionnaires were valid (the effective rate was 91.75%). Two months later, the employees evaluated their sense of self-worth and sense of role overload, while the leaders were asked to evaluate the proactive behavior of their subordinates. At Time 2, 406 questionnaires were collected and 372 questionnaires were valid (the effective rate was 91.62%). Among the valid response, the proportion of males is 61.29% and that of females is 38.70%. The age is mainly between 25 and 35 years old, with an average age of 28 years old. In terms of educational background, 25.54% of the participants have education of high school or below, 26.61% have junior college, 37.90% receive undergraduate education and 9.94% have graduate education or above. The result is shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Demographics |

Measures

All the scales used in this study are the previous maturity scales, which all adopt the 7-Point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”) to each of the items. The specific measurement are as follows:

(1) Perceived trust (time 1): it is measured with the scale of Gillespie (2011),27 with a total of 6 items evaluated by employees. The representative item is “My leader is willing to let me handle key tasks”. The Cronbach’s alpha value is 0.88 in this study.

(2) Sense of self-worth (time 2): it is measured with the scale of Rosenberg (1965),34 which is to measure the overall evaluation of employees on themselves, with a total of 7 items. The representative item is “I feel like a valuable person, at least on the same level as others”. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha value is 0.93.

(3) Sense of role overload (time 2): it is measured with the scale of Li Chaoping & Zhang Yi, (2009),35 with a total of 4 items for employees to score their role stress. The representative item is “I need to reduce part of my workload”. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha value is 0.91.

(4) Proactive behavior (time 2): it is measured with the scale of Frese & Fay (2001),29 with a total of 9 items, which is scored by the leaders to evaluate the employee’s proactive behavior. The representative item is “The employee is good at putting ideas into practice”. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha value of proactive behavior is 0.90.

(5) Reciprocation wariness (time 1): it is measured with the scale developed by Eisenberger, Cotterell, and Marvel (1987).36 There are 9 items in total which ask employees to score their actual cognition of themselves. The representative item is “I often feel like being used when others ask me for help.” The Cronbach’s alpha value of reciprocation wariness is 0.86 in this study.

(6) Control variables (time 1): The control variables in this paper include the gender (1= male, 2= female), age (years old), educational background (1= high school and below, 2= junior college, 3= undergraduate, 4= graduate student and above), and working years (1= less than five years, 2= six to ten years, 3=eleven to fifteen years, 4=more than sixteen years). Previous studies have pointed out that demographic characteristics will affect employees’ cognitive style and behavior style, so this paper controlled these control variables.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

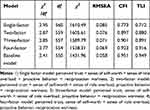

We conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) using Mplus 7.4 to test the factor structure of five variables measured (perceived trust, sense of self-worth, sense of role overload, proactive behavior and reciprocation wariness). According to Table 2, results shown that the hypothesized five-factor measurement model fit the data well (χ2/df = 2.41, df = 550, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.95). Specifically, we used the five-factor measurement model to compare with the fit of other models. The detailed factor model information in noted is Table 2. The results presented also showed that the alternative four-factor, three-factor, two-factor and single-factor models all achieved obviously poor fits. Thus, these analyses indicated the discriminant validity of these measures. In addition, the validity analysis was further tested. According to Table 3, the square root of AVE of each variable is larger than the correlations between the variable and other variables, also indicating that the discriminant validity is adequate.

|

Table 2 Comparison of Measurement Model |

|

Table 3 Model Discriminant Results |

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 4 describes the mean, standard deviation and correlation coefficient of all variable in our study. According to Table 4, perceived trust is positively correlated with sense of self-worth (r = 0.45, p < 0.01), sense of role overload (r = 0.12, p < 0.05) and proactive behavior (r = 0.37, p < 0.01). In addition, there was a positive correlation between sense of self-worth and proactive behavior (r = 0.27, p < 0.01); and there was a negative correlation between sense of role overload and proactive behavior (r = −0.12, p < 0.05). The inclusion or exclusion of control variables in this analysis did not change the study results.

|

Table 4 Descriptive Statistics: Mean, SD, and Inter-Item Correlation Co-Efficient |

Results of Hypotheses

The moderation effect is tested by hierarchical regression, and the results of regression analysis are shown in Table 5. Hypothesis 1 predicted that the relationship between perceived trust and sense of self-worth is moderated by reciprocation wariness, just as M2 of Table 5 shows that reciprocation wariness has a significant interaction effect on perceived trust. Specifically, the moderating effect of reciprocation wariness weakens the positive relationship between perceived trust and sense of self-worth (β = −0.19, p < 0.001). In this paper, a simple slope analysis is carried out according to the relevant recommendations of Aiken & West (1991)37 (see Figure 2). It can be seen from Figure 2 that the employees have low reciprocation wariness, the relationship between perceived leader trust and sense of role overload has a significant positive effect (1 SD, β = 0.90, p < 0.001). But when employees have high reciprocation wariness, the relationship between perceived leader trust and sense of self-worth is weakened (1 SD, β = 0.28, p < 0.01). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

|

Table 5 Regression Results |

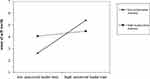

Hypothesis 2 predicted that the relationship between perceived leader trust and sense of role overload is moderated by reciprocation wariness. As M4 of Table 5 shows, the coefficient for the interaction of the perceived trust and employee’s reciprocation wariness is positive and significant (β = 0.11, p < 0.05). Using Aiken and West (1991)37 to plot the interaction effect (see Figure 3), we find that when employees have high reciprocation wariness, perceived leader trust has a significant positive effect on sense of role overload (1 SD, β = 0.31, p < 0.001), but when employees have low reciprocation wariness, the relationship between perceived leader trust and sense of role overload is not significant (−1 SD, β = −0.04, p = 0.77). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

|

Figure 2 The interactive effects of perceived leader trust and reciprocation on sense of self-worth. |

|

Figure 3 The interactive effects of perceived leader trust and reciprocation on sense of role overload. |

Hypothesis 3 further proposes a moderated mediated model: H3a predicts that the indirect effect of perceived leader trust on proactive behavior via sense of self-worth is moderated by employee’s reciprocation wariness. H3b predicts that the indirect effect of perceived leader trust on proactive behavior via sense of role overload is moderated by employee’s reciprocation wariness. In order to further verify hypothesis 3a and hypothesis 3b, this paper adopts the method recommended by Hayes38 and uses bootstrap to analyze the indirect effect at high or low values of the moderator. The results of the study are shown in Table 6. Specifically, the positive indirect effect between perceived trust and proactive behavior is mediated by sense of self-worth, which is more significant when reciprocation wariness is low (indirect effect = 0.06; 95% CI [0.007, 0.126]), but not significant when reciprocation wariness is high (indirect effect = 0.03; 95% CI [−.004, 0.67]). The difference between these indirect effects was statistically significant (difference = −0.03, 95% CI [−.011, −0.002]). Thus, Hypothesis 3a was supported. At the same time, the results showed the negative indirect effect between perceived trust and proactive behavior is mediated by sense of role overload, which is more significant when reciprocation wariness is high (indirect effect = −0.03; 95% CI [−.047, −0.010]), but not significant when reciprocation wariness is low (indirect effect = 0.01; 95% CI [−.022, 0.022]). The difference between these indirect effects was statistically significant (difference = −0.03, 95% CI [−.056, −0.006]). Therefore, Hypothesis 3b was supported.

|

Table 6 Conditional Indirect Effect |

Discussion

From the perspective of the perceived leader trust of employees, this paper examines the double-edged sword influence of perceived leader trust on employee behavior. We found that perceived leader trust will affect proactive behavior through employees’ subjective evaluation of the leader’s trust. Employee’s reciprocation wariness plays a moderating role in this relationship: when reciprocation wariness is high, perceived leader’s trust has a more significant negative indirect impact on proactive behavior through sense of role overload; When reciprocation wariness is low, perceived leader’s trust has a more significant positive and indirect influence on proactive behavior through sense of self-worth. In a word, by testing the moderated mediation model, this paper deeply analyzes the mechanism and boundary conditions of perceived leader trust influencing on employees’ psychological state and behavior, which contributes to the organizational trust and workplace proactive behavior research.

Theoretical Contributions

First and foremost, we contribute to the trait activation theory by building the linkages of two important organizational variables: perceived leader trust and employee’s proactive behavior. Nearly all previous studies considered being trust as beneficial to all concerned.15 At the same time, this perspective ignoring the individuals may differ in their willingness to exchange and reciprocity when being trusted. In practice, not all employees uniformly want being trust by their leaders.12 Based on the trait activation theory of perceived leader trust, our paper provides a new way of thinking to study of perceived leader trust. We also propose employees’ psychological state as an underlying mechanism linking perceived leader trust and its positive and negative employees’ follow-up work behavior and performance. By doing so, we contribute to a better understanding of the trait activation theory when applied in the organization workplace.

Secondly, this study further reveals the double-edged sword influences of perceived leader trust, specifically, the evaluation of sense of self-worth and the evaluation of sense of role overload, thereby promotes the cognition of the mechanism of perceived trust. Previous studies on the mechanism of trust mainly focus on positive aspects such as intrinsic motivation39 and team reflection.40 As a matter of fact, the role of perceived leader trust depends on the subjective evaluation of the trusted person.14 Therefore, this paper explores the mechanism of perceived trust from a new perspective. It is found that on the one hand perceived leader trust may have a positive impact on proactive behavior through increasing employees’ sense of self-worth, and on the other hand it may also have a negative impact on proactive behavior via increasing sense of role overload. Previous studies on perceived leader trust almost all examined the organizational impact of perceived trust from a single perspective, but did not integrate holistic perspectives. Therefore, this paper comprehensively expounds the overall mechanism of perceived leader trust on employees.

Thirdly, this paper introduces the important contingency condition of whether employees take proactive behavior when perceived their leader’s trust, that is, employee’s reciprocation wariness. Reciprocation wariness moderates the relationship between perceived trust, sense of self-worth and sense of role overload. This paper further investigates how reciprocation wariness moderates proactive behavior induced by perceived leader trust. The results show that when employee has high reciprocation wariness, perceived leader trust will increase the sense of role overload and then reduce the proactive behavior of employees; When employee’s reciprocation wariness is low, perceived leader trust will increase proactive behavior by improving their sense of self-worth. This shows that reciprocation wariness can effectively adjust the behavior pattern of employees coping with the leader’s trust, and provides a beneficial perspective for the research field of proactive behavior.

Practical Implications

Our findings shed light on important practical implications for organization managers who aim to promote employees’ proactive behavior, thereby generating a competitive advantage for their organization. First, our results imply that managers should choose appropriate management styles for employees with different reciprocation wariness level, so as to reduce employees’ negative feelings, such as sense of role overload. For employees with lower reciprocation wariness, simply expressing trust to them can motivate employees to make more feedback behaviors to their organization; For employees with high reciprocation wariness, managers need to adjust their encouragement strategies and express their trust through some practical behaviors, so as to adopt different management strategies according to the different personality traits of employees, to making the best use of their talents.

Second, managers also should consider the traits of employees when they are selecting the employees for the job.41 Based on our study result, individual differences, such as reciprocation wariness, are highly connected with the workplace behavior of how employees face their leader’s trust. These practices can enhance more proactive behavior when employees feel trust by their leaders, thus facilitating the organization’s thriving.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There are also some limitations in this study. First of all, although we adopt multi-source data collection method, the data of mediating variables (sense of self-worth and sense of role overload) and dependent variable (proactive behavior) are collected at the same time due to the limited conditions. However, the dependent variables proactive behavior, is evaluated by the direct leader, which can reduce the possible common method bias to a certain extent. Thus, we suggested that diary data collected across multiple time points or experimental method should be adopted in future research to better verify the causal relationship between these relationships. Secondly, although this study examines the moderating effect of reciprocation wariness, holding that reciprocation wariness affects employees’ view of their leader’s trust, additional moderators are recommended to be studied in further research. For instance, the relationship between employees and the leader may also determine how employees view their leader’s trust.42 Therefore, we encourage the future research to explore new contingency conditions from interpersonal relationship perspectives such as the dyadic relationship between employees and their leader.

Conclusion

This study extends the understanding of perceived leader trust, and explores the double-edged effects of perceived leader trust on employee’s proactive behavior. In particular, drawing on the social exchange theory and denoting the sense of self-evaluation as the vital transferring mechanism, we link perceived leader trust to both positive and negative influences on employees’ proactive behavior. We found that when reciprocation wariness is high, perceived leader’s trust has a more significant negative indirect impact on proactive behavior through the sense of role overload; When reciprocation wariness is low, perceived leader’s trust has a more significant positive and indirect influence on proactive behavior through the sense of self-worth. We hope that our study will encourage scholars to explore the consequences of perceived leader trust more comprehensively and identify possible moderators that can amplify the positive effects of perceived leader trust.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Zhejiang Gongshang University.

Data Sharing Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.72074195) and Project of Philosophy and Social Science Research, Ministry of Education, China (No. 19YJA630092).

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Ellis AM, Nifadkar SS, Bauer TN, et al. Newcomer adjustment: examining the role of managers’ perception of newcomer proactive behavior during organizational socialization. J Appl Psychol. 2017;102(6):993. doi:10.1037/apl0000201

2. Parker SK, Wang Y, Liao J. When is proactivity wise? A review of factors that influence the individual outcomes of proactive behavior. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2019;6(1):221–248. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015302

3. Wu C-H, Parker SK, Wu L-Z, et al. When and why people engage in different forms of proactive behavior: interactive effects of self-construals and work characteristics. Acad Manag J. 2018;61(1):293–323. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.1064

4. Parker SK, Williams HM, Turner N. Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91(3):636. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.636

5. Mayer RC, Davis JH, Schoorman FD. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad Manag Rev. 1995;20(3):709–734. doi:10.5465/amr.1995.9508080335

6. Lau DC, Lam LW, Wen SS. Examining the effects of feeling trusted by supervisors in the workplace: a self‐evaluative perspective. J Organ Behav. 2014;35(1):112–127. doi:10.1002/job.1861

7. Colquitt JA, Scott BA, LePine JA. Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: a meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(4):909. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.909

8. Fan J, Wei X, Ko I. How do hotel employees’ feeling trusted and its differentiation shape service performance: the role of relational energy. Int J Hosp Manag. 2021;92:102700. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102700

9. Colquitt JA, LePine JA, Piccolo RF, et al. Explaining the justice–performance relationship: trust as exchange deepener or trust as uncertainty reducer? J Appl Psychol. 2012;97(1):1. doi:10.1037/a0025208

10. Lau DC, Liu J, Fu PP. Feeling trusted by business leaders in China: antecedents and the mediating role of value congruence. Asia Pac J Manag. 2007;24(3):321–340. doi:10.1007/s10490-006-9026-z

11. Chen C, Zhang X, Sun L, et al. Trust is valued in proportion to its rarity? Investigating how and when feeling trusted leads to counterproductive work behavior. Acta Psychol Sin. 2020;52(3):329–344.

12. Baer MD, Frank EL, Matta FK, et al. Under trusted, over trusted, or just right? The fairness of (in)congruence between trust wanted and trust received. Acad Manag J. 2021;64(1):180–206. doi:10.5465/amj.2018.0334

13. Chen X, Zhu Z, Liu J. Does a trusted leader always behave better? The relationship between leader feeling trusted by employees and benevolent and laissez-faire leadership behaviors. J Business Ethics. 2021;170(3):615–634. doi:10.1007/s10551-019-04390-7

14. Baer MD, Dhensa-Kahlon RK, Colquitt JA, et al. Uneasy lies the head that bears the trust: the effects of feeling trusted on emotional exhaustion. Acad Manag J. 2015;58(6):1637–1657. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0246

15. Skinner D, Dietz G, Weibel A. The dark side of trust: when trust becomes a ‘poisoned chalice’. Organization. 2013;21(2):206–224. doi:10.1177/1350508412473866

16. Colquitt JA, Rodell JB. Justice, trust, and trustworthiness: a longitudinal analysis integrating three theoretical perspectives. Acad Manag J. 2011;54(6):1183–1206. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.0572

17. Tett RP, Simonet DV, Walser B, et al. Trait activation theory. In: Christiansen N, Tett R, editors.H andbook of Personality at Work. 2013:71–100.

18. Pelham BW, Swann WB. From self-conceptions to self-worth: on the sources and structure of global self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(4):672. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.4.672

19. She Z, Li B, Li Q, et al. The double‐edged sword of coaching: relationships between managers’ coaching and their feelings of personal accomplishment and role overload. Hum Resour Dev Q. 2019;30(2):245–266. doi:10.1002/hrdq.21342

20. Eisenberger R, Shoss MK, Karagonlar G, et al. The supervisor POS–LMX–subordinate POS chain: moderation by reciprocation wariness and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. J Organ Behav. 2014;35(5):635–656. doi:10.1002/job.1877

21. Wayne SJ, Shore LM, Bommer WH, et al. The role of fair treatment and rewards in perceptions of organizational support and leader-member exchange. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(3):590. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.590

22. Zhang Z-X, Han Y-L. The effects of reciprocation wariness on negotiation behavior and outcomes. Group Decis Negot. 2007;16(6):507–525. doi:10.1007/s10726-006-9070-6

23. Duxbury L, Higgins C, Halinski M. Identifying the antecedents of work-role overload in police organizations. Crim Justice Behav. 2015;42(4):361–381. doi:10.1177/0093854814551017

24. Yousef DA. Job satisfaction as a mediator of the relationship between role stressors and organizational commitment: a study from an Arabic cultural perspective. J Manag Psychol. 2002;17(4):250–266. doi:10.1108/02683940210428074

25. Örtqvist D, Wincent J. Prominent consequences of role stress: a meta-analytic review. Int J Stress Manag. 2006;13(4):399. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.13.4.399

26. Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, et al. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(3):499. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

27. Gillespie N. 17 Measuring trust in organizational contexts: an overview of survey-based measures. In: Lyon F, Möllering G, Saunders MNK, editors. Handbook of Research Methods on Trust. 2011:175.

28. Karagonlar G, Eisenberger R, Aselage J. Reciprocation wary employees discount psychological contract fulfillment. J Organ Behav. 2016;37(1):23–40. doi:10.1002/job.2016

29. Frese M, Fay D. 4. Personal initiative: an active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Res Organ Behav. 2001;23:133–187. doi:10.1016/S0191-3085(01)23005-6

30. Froidevaux A, Koopmann J, Wang M, et al. Is student loan debt good or bad for full-time employment upon graduation from college? J Appl Psychol. 2020;105(11):1246.

31. Sun S, Wang N, Zhu J, et al. Crafting job demands and employee creativity: a diary study. Hum Resour Manage. 2020;59(6):569–583. doi:10.1002/hrm.22013

32. Dollard MF, Winefield HR, Winefield AH, et al. Psychosocial job strain and productivity in human service workers: a test of the demand‐control‐support model. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2000;73(4):501–510. doi:10.1348/096317900167182

33. Hellgren J, Sverke M, Isaksson K. A two-dimensional approach to job insecurity: consequences for employee attitudes and well-being. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 1999;8(2):179–195. doi:10.1080/135943299398311

34. Rosenberg M. Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). ACT. 1965;61(52):18.

35. Chaoping L, Yi Z. The effect of role stressors on teachers’ physical and mental health. Psychol Dev Educ. 2009;25(1):114–119.

36. Eisenberger R, Cotterell N, Marvel J. Reciprocation ideology. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53(4):743. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.4.743

37. Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park: Sage; 1991:212.

38. Hayes AF. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behav Res. 2015;50(1):1–22. doi:10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

39. Baldé M, Ferreira AI, Maynard T. SECI driven creativity: the role of team trust and intrinsic motivation. J Knowl Manag. 2018;22(8):1688–1711. doi:10.1108/JKM-06-2017-0241

40. Rong P, Li C, Xie J. Learning, trust, and creativity in top management teams: team reflexivity as a moderator. Soc Behav Pers. 2019;47(5):1–14. doi:10.2224/sbp.8572

41. Islam MN, Furuoka F, Idris A. Mapping the relationship between transformational leadership, trust in leadership and employee championing behavior during organizational change. Asia Pac Manag Rev. 2021;26(2):95–102. doi:10.1016/j.apmrv.2020.09.002

42. Martin R, Thomas G, Legood A, et al. Leader–member exchange (LMX) differentiation and work outcomes: conceptual clarification and critical review. J Organ Behav. 2018;39(2):151–168. doi:10.1002/job.2202

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.