Back to Journals » Nursing: Research and Reviews » Volume 12

Family Members’ Experiences with the Healthcare Professionals in Nursing Homes – A Survey Study

Authors Momeni P , Ewertzon M , Årestedt K, Winnberg E

Received 26 October 2021

Accepted for publication 9 February 2022

Published 20 March 2022 Volume 2022:12 Pages 57—66

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NRR.S345452

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Natasha Hodgkinson

Pardis Momeni,1 Mats Ewertzon,1,2 Kristofer Årestedt,3 Elisabeth Winnberg1

1Department of Health Care Sciences, Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, Stockholm, Sweden; 2Swedish Family Care Competence Centre, Kalmar, Sweden; 3Department of Research, Linnaeus University, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, Regiona Kalmar County, Kalmar, Sweden

Correspondence: Pardis Momeni, Department of Health Care Sciences, Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, Stockholm, Sweden, Tel +46 707555158, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The purpose was to investigate family members’ experiences of the healthcare professionals’ approach and feeling of alienation in nursing homes.

Methods: This study had a cross-sectional design collecting data from seven nursing homes in Sweden using the Family Involvement and Alienation Questionnaire – Revised (FIAQ-R). The final sample consisted 133 family members (response rate 42.6%). Data were analyzed with a variety of rank-based, non-parametric statistical methods.

Results: Family members in general experienced a positive approach from the healthcare professionals and considered that as being of the very highest importance. This could be explained by the skewed sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. The concept of continuity generated the most comments of a negative character indicating the importance of organizational factors in nursing homes.

Conclusion: The results indicate the need to improve continuity in the care of older persons in nursing homes by limiting the amount of different health care professionals surrounding the older person. Also, it highlights the importance of having a specific contact person assigned to each older person living in nursing homes.

Keywords: family member, health care professional, FIAQ, nursing home, approach, alienation

Introduction

The amount of time spent in nursing homes today is decreasing, because older persons live in their own homes as long as possible. When arriving to the nursing home, they are often frail and ill and have a short-expected lifetime.1,2 The transition from one’s own home to a nursing home leads to reduced burden of care, feelings of safety and some relief for the family members, but it can also evoke feelings of guilt and remorse.3,4 Family members’ participation and involvement in nursing home care have been well explored in a wide range of qualitative studies.3,5–9 One study5 showed that the potential contribution of family members can promote well‐being for both the older person and the healthcare professionals. Family members were more willing to help in the care than the healthcare professionals were aware of. When family members felt that they had no control and were not being heard, small issues had the potential to become magnified and develop into problems. Another study9 showed that family members over 65 years of age reported a higher degree of communication and trust than did younger family members in their relationship with the healthcare professionals. In addition, if the older person had a personal contact person among the staff, family members experienced a higher degree of participation in the care. A similar study showed a complex side to the concept of participation,6 concluding that the healthcare professionals should enable family members to participate according to their own preferences. They emphasized that one should not take for granted that family members always want to participate.

A concept that is relevant to participation, although contrary to it, is alienation, which means to feel socially isolated or rejected, ie not participating or being involved. This concept has been studied among family members in the context of psychiatric care.10–12 These studies showed that being approached positively by the health care professionals was associated with a lower level of feeling of alienation. To our knowledge, there has been no research concerning alienation among family members in the context of the care of older people.

Family members’ experiences of approach have been explored in similar terms, such as encounter. Family members to people with long-term illness have shown that they want to be acknowledged and have a familiar and trusting relationship with the healthcare professionals.13 It was also important to be greeted, in a welcoming atmosphere, with respect. Another study showed that a collaboration between the nurse and the family members was highly important.14 Furthermore, family members felt ignored and not being involved in the care.15 However, a deeper understanding of the feeling of being ignored or alienated in the care of the older person has not yet been established. To summarize, previous studies on family member’s experiences of nursing homes have mostly had qualitative designs and have provided valuable insights to their experiences of encounter and participation. Studies with quantitative designs could further enlighten this body of knowledge.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate family members’ experiences of the healthcare professionals’ approach, and feeling of alienation, in nursing homes.

Materials and Methods

Design

This survey had a cross-sectional design.

Sample and Procedure

Inclusion criteria were to be an adult (≥18 years of age) family member to a person living in a nursing home. In this study, a family member refers to a relative, partner or friend who actively contributes with practical and/or psycho-social support. The term healthcare professionals refers to nurses’ aides, nursing assistants, registered nurses, occupational therapists, physical therapists and physicians working in the nursing home. A total of 19 nursing homes in a metropolitan area were approached for participation in the study, including nursing homes located in different socio-economic areas, and both public and privately owned establishments. Seven nursing homes agreed to participate.

The primary family member who had the main continuous on-going contact with the healthcare professionals was already well documented and known by the nursing home in the residents’ files. These were then provided to the researcher by the head of each nursing home. Written information about the study, the voluntariness of participation, and a questionnaire were delivered by mail. Family members accepted participation by completing the questionnaire, which was returned to the researchers by a prepaid reply envelope. One reminder was sent out a few weeks after the first invitation. In total, 312 questionnaires were delivered, of which 137 were returned. Four questionnaires were excluded due to missing data above 25%. Thus, the final sample included 133 family members, which corresponds to a response rate of 42.6%.

The Questionnaire

The questionnaire included two parts; the first part included questions regarding participants’ socioeconomic background, including gender, age, civil status, relationship to the patient, educational level, residency, and place of upbringing, and the second part included the Family Involvement and Alienation Questionnaire – Revised (FIAQ-R), the questionnaire measures family members´ experiences of the healthcare professionals approach, as well as feelings of alienation from provision of care16. FIAQ-R has recently been validated for the care of the older person, among other care contexts.16

The FIAQ-R consists of two scales, Experience of approach and Feeling of alienation. Experience of approach includes 21 items covering four concepts: openness, confirmation, co-operation and continuity. Openness described as the family members’ experience of important information about the patient’s state of health. Confirmation described as the family members experiencing that the healthcare professionals are able to both see and listen to them as important persons. Cooperation, meaning that the healthcare professionals’ value them and their opinions as important. Lastly, continuity is characterized by the family members experiencing continuity in their contact with the healthcare professionals, having the opportunity to meet the same person(s), regular contact and a clear purpose for the contact.

Each of the 21 items are rated on two different response scales; one about the actual experience of approach (that is, the actual experience of the professionals’ approach) and one about the subjective importance of approach (that is, the importance they ascribed to the professional’s approach). Each item is answered on a four-point Likert scale, ranging between “completely disagree” (1) and “completely agree” (4) for actual experience and between “of no importance” (1) and “of the very highest importance” (4) for subjective importance.

The second scale of the FIAQ-R, Feeling of alienation (that is, whether family members experience themselves as being alienated from the professional care) includes eight items, which cover two concepts: powerlessness and social isolation.10 Powerlessness, described as the family member having a sense of low expectancy, meaning that others decide regarding the care of the patient and that the family member is powerless in that sense. The family member experiences a lack of influence over the received care. Social isolation is characterized by the family member having feelings of being excluded or rejected from the care of the patient. The response format is a four-point Likert scale, ranging between “Completely disagree” (1) and “Completely agree” (4).

For both scales (experience of approach and feeling of alienation), the median value of the responses is used for the scale scores. Higher median scores for the actual experience of approach and for the subjective importance indicate a positive response, meaning that the approach is experienced as positive and is valued as important. Similarly, regarding feeling of alienation, higher median scores indicate that the family members feel alienated. Finally, the FIAQ-R includes an open-ended question to allow comments about the experience of approach and feeling of alienation;

Is there anything else that you think is important about the approach of the healthcare professionals which has not been addressed in the above questions? If so, it would be most valuable if you could describe this below.

Data Analysis

Statistical Analyses

The assessments in the FIAQ-R are subjective and the data consists of ordered categories. As in previous studies using the FIAQ or the FIAQ-R10–12,17–19 data were analyzed using rank-based, non-parametric statistical methods.20 The median level (Md) and quartiles (Q1;Q3) were used to describe the response profiles. A global score for each scale and its concepts was calculated by the median scoring technique for multi-items.21 Within-group analyses were conducted using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (two related groups) or Friedman’s test (three or more related groups). Associations between the scales were evaluated by the Spearman rank order correlation coefficient (rs). The significance level was set at p<0.05. Data was analyzed using SPSS 22.1 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Qualitative Analysis of the Open-Ended Question

The answers to the open-ended question in the FIAQ-R were analyzed by direct content analysis according to Hsieh and Shannon.22 This method describes a deductive approach to content analysis, using a theory or a theoretical framework to categorize the written text. Thus, the analysis of the open-ended question was guided by the six concepts in the FIAQ-R. First, the transcripts were thoroughly and repeatedly read by two of the members of the research group (PM and EW), independently, to gain a holistic depiction. Secondly, sentences were marked in the text with specific codes for the six different concepts. To ensure the credibility and dependability of the analyses, the preliminary coding for the sentences was then discussed by the two members together in a third step. For a few citations, a discrepancy was identified, and after discussion it was agreed that these should be assigned to one concept. In the fourth step of the analysis, all the citations were discussed with a third member of the research group (ME) and again a few citations were revised until agreement was achieved. Finally, the citations were divided into positive and negative comments.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

The final sample included 133 family members, almost three quarters of whom were female (n=93, 70%). The mean age was 63 years (SD=11). The most common relationships to the older person were children (n=98, 74%), partners (n=20, 15%), siblings (n=3, 2%), and other (n=12, 9%), such as friends and nephews. A majority were brought up in Sweden (n=125, 94%), lived in a metropolitan area (n=122, 92%), were in a partnership (n=104, 78%), and had a university degree (n=99, 74%).

Experiences of Approach and Feeling of Alienation

The median level of the responses to the statements of the actual experience of approach was “Partly agree” (3) (Q1=3; Q3=4), which indicates that the family members on average experienced a positive approach from the healthcare professionals. The median level of subjective importance was “Of the very highest importance” (4) (Q1=3; Q3=4), which indicates that the family members on average considered the healthcare professionals’ approach as being of the very highest importance. The median level for Feeling of alienation was “Completely disagree” (1) (Q1=1; Q3=2), which indicates that the family members on average felt that they were not being alienated from the professional care.

The Response Profiles Regarding the Concepts in the FIAQ-R

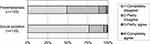

Figure 1 shows the response profiles regarding the degree of agreement in the concepts in the actual experience of approach. The median levels of all the concepts were “Partly agree” (3), which indicates that the family members to a large extent experience the healthcare professionals’ approach toward them as being continuous, showing openness, being confirmatory, and being co-operative. No significant differences between the concepts were detected.

Figure 2 shows the response profiles regarding the degree of agreement in concept in subjective importance of approach. The median levels of the concepts of continuity and openness were “Of the very highest importance (4)”, which indicates that the family members considered continuity and openness in the healthcare professionals’ approach toward them as being of the highest importance. Confirmation and co-operation were rated lower, “Of great importance” (3), which indicates that the family members considered confirmatory and cooperative aspects in the healthcare professionals’ approach toward them as also being very important aspects. Friedman´s test showed significant differences between the four concepts (χ2=15.87, p=0.001). The Wilcoxon signed-rank post-hoc test showed that continuity was scored significantly higher than confirmation (Z= −2.35; p=0.02) and co-operation (Z=−2.67; p=0.02). In addition, openness was scored significantly higher than confirmation (Z=−2.92; p=0.004) and co-operation (Z=−3.14; p=0.002).

Figure 3 shows the response profiles regarding the degree of agreement in concepts in the Feeling of alienation scale. The median level of the concept of social isolation was “Completely disagree” (1), which indicates that the family members to a large extent did not experience themselves as being socially isolated from the professional care. The concept of powerlessness was scored higher, “Partly disagree” (2), which indicates that the family members experienced themselves as being only partially powerless. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed a significant difference between the two concepts (Z=5.75; p=0.001).

Associations Between the Scales in the FIAQ-R

Significantly positive association were found between actual experiences of approach and the subjective importance of approach (rs=0.46, p<0.001), the positive correlation indicates that a higher level of being approached positively is associated with a higher level of considering the approach as being important, and vice versa. Significantly negative association were found between actual experiences of approach and feeling of alienation (rs=−0.58, p<0.001), the negative correlation indicates that a higher level of being positively approached is associated with a lower level of feeling alienated, and vice versa. Significantly negative association were also found between subjective importance of approach and feeling of alienation (rs=−0.25, p=0.004), the negative correlation indicates that a higher level of approach as important is associated with a lower level of feeling alienated, and vice versa.

Qualitative Aspects Consistent with Concepts in the FIAQ-R

The answers to the open question generated a total of 13 pages of transcripts from 59 family members. A total of five pages with 69 citations stated by 33 family members (of 133 = 24.8%) were relevant to the concepts in the FIAQ-R. All categories but one (the concept of powerlessness) were represented in the answers. Overall, there were an equal number of positive and negative comments (34 positive and 35 negative). The largest group of comments (28/69 = 40.6%) were applicable to the concept of continuity (Figure 4). This concept received mainly negative comments from the family members (17/28 = 60.7%). The remaining eight pages of transcripts were not analyzed in this study due to irrelevance to the concepts of the FIAQ-R.

|

Figure 4 Categorization of the open question with regards to the concepts of FIAQ-R, with number of positive and negative comments by the family members respectively. |

An example of a negative comment associated with the concept of continuity was:

I would like the staff to have a clearer, continuous follow-up with me. Sometimes, it has been difficult to maintain good routines due to staff turnover and an excessive workload for the staff. When there has not been a continuity regarding the contact person, I have been responsible for things being done, such as dental visits, foot care, showers, etc.

Most of the negative comments regarding continuity were related to the feeling of there being a high turnover of healthcare professionals and many extra staff working in the units.

The concepts of openness, confirmation and cooperation received more positive comments than they did negative comments (Figure 4). An example of a positive comment associated with the concept of openness was: “Impressed by the nurses’ efforts to convey in such a gentle way that the end was near and to assist and guide me in this situation.”

A positive comment associated with the concept of confirmation was:

Genuine staff well-being that is reflected in meetings – in the corridors or in scheduled meetings - never feeling like a troublesome family member. About [nursing home name] I can only say that I wish I can go there myself when I can no longer take care of myself - the care provided by the care staff is fantastic (and I have experience from two parents at other places) - sometimes I get more support and encouragement from them than from my own healthcare center.

A positive comment associated with the concept of co-operation was: “The staff wanted to receive information from family members, in order to provide person-centered care.”

The concept of social isolation received two comments, both were negative (Figure 4): “As a family member, having a voice and making an impact takes a lot of work, and a lot of effort.”

Discussion

This study aimed to explore family members’ experiences of the healthcare professionals’ approach and feeling of alienation. Overall, most family members expressed mainly positive experiences of approach from the healthcare professionals in the nursing homes. One can only speculate about the factors contributing to this. For example, one factor that further needs attention is the environment in which the healthcare professionals are working, which can influence how family members experience the care provided to the older persons. Nurses’ work is influenced by the environment in which they practice. In good work environments, there are adequate staff and resources, supportive managers, strong nursing foundations for care, productive relationships with colleagues, input into organizational affairs, and opportunities for advancement.23 It could be the case that the nursing homes participating in this study are biased in terms of being well-functioning organizations. We are aware that all but one of the nursing homes were in high socio-economic areas, and that several nursing homes in lower socio-economic areas declined participation. It is possible that the finances of the nursing homes could be a factor that contributes to creating a good working environment, resulting in a friendlier communication by the healthcare professionals to the family members. However, multiple barriers to good communication between nursing homes and family caregivers were identified in an American study, such as understaffing, high turnover, poor intra-staff communication and the nursing staffs’ perception that family members complain readily but rarely offer praise.24 Today, over ten years later, the situation in nursing homes has hopefully improved significantly, which our results may be an example of. However, to continue improvement in the care of older persons in nursing homes, further research studies and implementation projects are needed that address communication between the healthcare professionals in nursing homes and the family members.

The results also showed that most family members did not feel alienated from the care of the older person. This is contrary to studies performed in the context of psychiatric care, which show higher levels of alienation.10–12 This could be due to the compulsory nature of the care,10 and also the patient not always wanting the family to be involved.25 Such a situation can lead to dilemmas in the healthcare professionals’ meetings with the family members.26 For example, when healthcare professionals receive sensitive information from the family members regarding the patient, and then not being able to share this with the patient due to possible negative consequences.

One concept in the FIAQ-R is continuity, which was shown to be an important factor for the family members. Statistically, the results indicated a significantly more positive response for the importance of continuity than for the importance of confirmation and co-operation. Continuity was also shown to receive mostly positive responses on experience of approach. However, the analysis of the open-ended question indicated a more nuanced picture, with a majority of the comments being of a negative character. In our study, continuity of care was defined as the possibility to meet the same person at the care unit, being able to have regular contact with the healthcare professionals and being able to see a clear purpose of the contact. The family members commented on many different healthcare professionals around the older person. This is a well-known situation in many nursing homes, which has generated a substantial amount of criticism, as it does not promote continuity of care.27 Discussions concerning care have led to many studies aiming to examine what quality of care means for residents in nursing homes,28 and also what it means for family members.29 There are probably many factors involved that contribute to this problem, for example, organizational and economic factors. How to improve the continuity of care needs to be actively investigated. Such an improvement is particularly important for the older person, but also for the family members. Further research may help shed light on this issue.

Continuity has been studied in other care contexts for example patients with heart failure who described having access to healthcare professionals as important for continuity of care.30 When this worked well, the family member felt secure and a mutual, trustworthy relationship was created between the patient, the family member and the healthcare professional. The study concluded that healthcare professionals should plan and carry out healthcare in collaboration with patients and next of kin. In a health policy report, continuity in care was stated just as important for family members as it is for the patient and the healthcare professionals.31 Fragmented care, conflicting advice and inadequate coordination of care and treatment contribute to lack of continuity of care. This suggests the need for new collaboration models that include the healthcare professionals, the patients and their families, in order to enhance the continuity of care.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that need to be considered. The seven nursing homes that decided to participate were all except one from geographical areas with high socio-economic status. This can explain the high educational level among the participants. A related weakness is the low response rate; less than half of the invited family members returned the questionnaire. As the design of the study did not allowed any drop out analyses, it is difficult to draw any conclusions about how representative the study sample was. For these reasons, the quantitative findings should be generalized with care until further studies confirm our results. However, the quantitative findings in combination with the qualitative findings contribute important knowledge about family members’ experiences of approach in encounters with healthcare professionals and feeling of alienation in the professional care in nursing homes. No a priori sample size calculation was conducted, since this study was part of a larger project that includes different care contexts. The sample size can be judged as sufficient according to the analyses that have been conducted. However, as the sample size was somewhat small, no corrections were made to manage the multiple post-hoc tests. Even if such corrections are recommended to prevent type I errors in post hoc analyses, they can result in type II errors in studies with small samples.

Other methodological issues that were considered included our decision to add an open-ended question where the participants could freely elaborate on any issue. An interview design with a smaller number of family members could have generated more depth regarding the family members’ descriptions of their experiences of approach and feeling of alienation, which could be of interest for future studies. However, the transcripts from the open question clearly showed that the family members were engaged and had many thoughts to express and provided further insight into the experiences of the family members.

Conclusion

The relationship between family members to older persons living in nursing homes and the healthcare professionals has been studied using the FIAQ-R questionnaire with a focus on approach and feeling of alienation. Most family members in this study expressed mainly positive experiences of approach in their encounters with the healthcare professionals. In addition, most family members did not feel alienated from the care of the older person. The concept of continuity generated the most comments of a negative character when answering the open-ended question, indicating the need to improve continuity in the care of older persons in nursing homes.

Implications for Practice

Health care professionals in nursing homes should be aware of family members’ wish to be involved and acknowledged to nourish a good relationship. There is a need to improve continuity in the care of older persons which can impact the older persons’ quality of care, but also the family members’ experience of care. Family members experienced a high turnover of the healthcare professionals. Limiting the number of personnel in the care of the older person is needed to improve the continuity of care. Health care managers should consider the negative consequences organizational factors have on both the older person and consequently the family members.

Ethical Considerations

The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm has approved the study (No. 2014/583-31). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants, and the participants’ responses were kept confidential and coded for the research analyses. The participants informed consent included publication of anonymized responses.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the care units and the family members who participated in the study. We also thank Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College for financial support and Katarina Almqvist for data collection, data management and the transcription of the qualitative data.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, have agreed on the journal to which the article was submitted, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research project received funding from Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. Onder G, Carpenter I, Finne-Soveri H, et al. Assessment of nursing home residents in Europe: the Services and Health for Elderly in Long TERm care (SHELTER) study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:5. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-5

2. Wiles JL, Leibing A, Guberman N, Reeve J, Allen RE. The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. Gerontologist. 2012;52(3):357–366. doi:10.1093/geront/gnr098

3. Rustad EC, Seiger Cronfalk B, Furnes B, Dysvik E. Next of kin’s experiences of information and responsibility during their older relatives’ care transitions from hospital to municipal health care. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(7–8):964–974. doi:10.1111/jocn.13511

4. Eika M, Espnes GA, Soderhamn O, Hvalvik S. Experiences faced by next of kin during their older family members’ transition into long-term care in a Norwegian nursing home. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(15–16):2186–2195. doi:10.1111/jocn.12491

5. Davies S, Nolan M. ‘Making it better’: self-perceived roles of family caregivers of older people living in care homes: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(3):281–291. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.04.009

6. Ekström K, Spelmans S, Ahlström G, et al. Next of kin’s perceptions of the meaning of participation in the care of older persons in nursing homes: a phenomenographic study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2019;33(2):400–408. doi:10.1111/scs.12636

7. Janlöv AC, Hallberg IR, Petersson K. Family members’ experience of participation in the needs of assessment when their older next of kin becomes in need of public home help: a qualitative interview study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(8):1033–1046. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.11.010

8. Lao SS, Low LPL, Wong KKY. Older residents’ perceptions of family involvement in residential care. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2019;14(1):1611298. doi:10.1080/17482631.2019.1611298

9. Westergren A, Behm L, Lindhardt T, Persson M, Ahlström G. Measuring next of kin’s experience of participation in the care of older people in nursing homes. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0228379. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0228379

10. Ewertzon M, Lützén K, Svensson E, Andershed B. Family members’ involvement in psychiatric care: experiences of the healthcare professionals’ approach and feeling of alienation. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010;17(5):422–432. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01539.x

11. Weimand BM, Israel P, Ewertzon M. Families in Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams in Norway: a cross-sectional study on relatives’ experiences of involvement and alienation. Community Ment Health J. 2018;54(5):686–697. doi:10.1007/s10597-017-0207-7

12. Johansson A, Anderzén-Carlsson A, Ewertzon M. Parents of adult children with long-term mental disorder: their experiences of the mental health professionals’ approach and feelings of alienation - a cross sectional study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2019;33(6):129–137. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2019.10.002

13. Zotterman AN, Skär L, Söderberg S. Meanings of encounters for close relatives of people with a long-term illness within a primary healthcare setting. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018;19(4):392–397. doi:10.1017/S1463423618000178

14. Kiljunen O, Kankkunen P, Partanen P, Välimäki T. Family members’ expectations regarding nurses’ competence in care homes: a qualitative interview study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2018;32(3):1018–1026. doi:10.1111/scs.12544

15. Westin L, Öhrn I, Danielson E. Visiting a nursing home: relatives’ experiences of encounters with nurses. Nurs Inq. 2009;16(4):318–325. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1800.2009.00466.x

16. Ewertzon M, Alvariza A, Winnberg E, et al. Adaptation and evaluation of the Family Involvement and Alienation Questionnaire for use in the care of older people, psychiatric care, palliative care and diabetes care. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(8):1839–1850. doi:10.1111/jan.13579

17. Ewertzon M, Andershed B, Svensson E, Lützén K. Family members’ expectation of the psychiatric healthcare professionals’ approach towards them. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(2):146–157. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01647.x

18. Johansson A, Ewertzon M, Andershed B, Anderzén-Carlsson A, Nasic S, Ahlin A. Health-related quality of life–from the perspective of mothers and fathers of adult children suffering from long-term mental disorders. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29(3):180–185. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2015.02.002

19. Sjöström N, Waern M, Johansson A, Weimand B, Johansson O, Ewertzon M. Relatives´ experiences of mental health care, family burden and family stigma: does participation in patient-appointed resource group assertive community treatment (RACT) make a difference? Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2021;1:1–10. doi:10.1080/01612840.2021.1924322

20. Altman D. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. London: Chapman & Hall; 1991.

21. Svensson E. Construction of a single global scale for multi-item assessments of the same variable. Stat Med. 2001;20(24):3831–3846. doi:10.1002/sim.1148

22. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

23. Song Y, Hoben M, Norton P, Estabrooks CA. Association of work environment with missed and rushed care tasks among care aides in nursing homes. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1920092. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20092

24. Majerovitz SB, Mollott RJ, Rudder C. We’re on the same side: improving communication between nursing home and family. Health Commun. 2009;24:12–20. doi:10.1080/10410230802606950

25. Lakeman R. Family and carer participation in mental health care: perspectives of consumers and carers in hospital and home care settings. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15(3):203–211. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01213.x

26. Sjöblom L-M, Wiberg L, Pejlert A, Asplund K. How family members of a person suffering from mental illness experience psychiatric care. Int J Psychiatr Nurs Res. 2008;13(3):1–13.

27. Habjanič A, Saarnio R, Elo S, Turk DM, Isola A. Challenges for institutional elder care in Slovenian nursing homes. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(17–18):2579–2589. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.04044.x

28. Gilbert AS, Garratt SM, Kosowicz L, Ostaszkiewicz J, Dow B. Aged care residents’ perspectives on quality of care in care homes: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Res Aging. 2021;43(7–8):294–310. doi:10.1177/0164027521989074

29. Shippee TP, Henning-Smith C, Gaugler J, Held R, Kane RL. Family satisfaction with nursing home care. Res Aging. 2017;39(3):418–442. doi:10.1177/0164027515615182

30. Östman M, Bäck-Pettersson S, Sandvik A-H, Sundler AJ. “Being in good hands”: next of kin’s perceptions of continuity of care in patients with heart failure. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:375. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1390-x

31. Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care, a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1064–1071. doi:10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.