Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 13

Factors associated with the doctor–patient relationship: doctor and patient perspectives in hospital outpatient clinics of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China

Authors Qiao T, Fan Y, Geater AF , Chongsuvivatwong V , McNeil EB

Received 2 October 2018

Accepted for publication 14 May 2019

Published 16 July 2019 Volume 2019:13 Pages 1125—1143

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S189345

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Naifeng Liu

Tingting Qiao,1 Yancun Fan,1 Alan F Geater,2 Virasakdi Chongsuvivatwong,2 Edward B McNeil2

1School of Health Management, Inner Mongolia Medical University, Hohhot 010010, Inner Mongolia, People’s Republic of China; 2Epidemiology Unit, Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai 90110, Songkhla, Thailand

Purpose: The doctor–patient relationship (DPR) in People’s Republic of China is very tense. This study aimed to provide some explanation by exploring factors influencing the DPR from doctors’ and patients’ perspectives.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted in one provincial and one city-level general public hospital in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of People’s Republic of China. The Difficult Doctor–Patient Relationship Questionnaire (DDPRQ-10) and the Patient–Doctor Relationship Questionnaire (PDRQ-9) were used to assess the quality of the DPR from 226 doctors, and 713 patients’ perspectives, respectively. Multivariate linear regression was used to identify factors significantly associated with the doctors’ and patients’ perceptions of the DPR by assessing coefficients of total effect and their 95% confidence interval.

Results: The result revealed that provincial-level doctors had a higher DDPRQ-10 score than city-level doctors. Worse DDPRQ-10 scores were seen for doctors who worked in the Internal Medicine departments were aged between 31 and 40 years, held a master’s degree, were dissatisfied with their income, worked more than 40 hrs per week, felt pressure at work, considered the hospital environment to be bad, often felt affected by negative media reports and had defensive behaviors. Patients visiting the provincial hospital had a lower PDRQ-9 score than those from the city-level hospital. Lower PDRQ-9 scores were also seen for patients who were of Mongolian ethnicity, were dissatisfied with their income, waited longer to see the doctor, had a shorter doctor consultation time, had lower expectations of their treatment result, had a low level of trust in the doctor, regarded the hospital environment as bad and those who were frequently influenced by negative media reports.

Conclusion: This study may provide a useful model to raise the quality of the DPR and to supply evidence for health policy makers and administrators to formulate strategies for reducing the problem of tense DPR in Chinese hospitals.

Keywords: outpatient, doctor-patient relationship, medical dispute, patient satisfaction, People’s Republic of China, health policy

Introduction

The doctor–patient relationship (DPR) is a complex concept which begins when a patient consults a doctor and subsequently tends to follow the doctor’s guidance.1,2 A relationship which is harmonious can promote social harmony and a trusting relationship can promote a patient’s ability to cope with their illness.3–5 whereas a poor DPR may lead to inferior quality of health care, patient anxiety, difficulty in coping, poor compliance, and “doctor-shopping” or non-scientific forms of treatment.3,5 Doctors’ wariness of medical disputes by dissatisfied patients may induce them to order unnecessary investigations and overprescribe medications.6

The DPR is currently in crisis in People’s Republic of China.7 Its quality has continuously worsened and, in recent years, Chinese doctors have been facing increased threats to their personal safety at work in the form of verbal and physical abuse, injury, and even murder, by dissatisfied patients or their relatives throughout the country.8 Such attacks have become an almost daily routine.8–10 The Chinese Hospital Association reported that violence against medical workers increased steadily from 57 events in 2010 to 150 events in 2014. Medical practice is now regarded as a high-risk occupation in People’s Republic of China and this view is having an impact on young doctors and many students are now not willing to study medicine.11 Moreover, the general level of patients’ trust in doctors is low.12

A number of previous studies have attempted to explain the reasons for a poor DPR from both doctors’ and patients’ perspectives. For example, some researchers have described how doctors and patients, even if coming from the same social and cultural background, tend to view ill-health in very different ways.3 Furthermore, because of the technological superiority and skilled nature of their occupation, doctors generally assume an authoritative role which, if not accepted by the patient, may lead to conflicts.1 There tends to be a significant lack of concordance between doctors’ objectives and patients’ expectations, creating a gap in the DPR13 and undermining the trust and relationship between doctor and patient.3 Lack of communication skills on the part of doctors such as a tendency to use medical terms and not listening thoroughly to the patients’ complaints can further obstruct the development of a good DPR.14 However, Le and some other researchers argued that a higher proportion of doctors than of patients consider the DPR to be very tense and that the current situation of poor DPR has more influence on doctors.15 Factors influencing the DPR from the doctors’ side have been reported to include communication barriers, pressure of work, consciousness of occupational risk, doctors’ social status, and hospital environment.15

Based on the literature, it is apparent that the growing tensions in the DPR and the high incidence of medical disputes have a great influence on Chinese society. Factors affecting the quality of the DPR are varied. Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region is one of the five ethnic autonomous regions of People’s Republic of China. These are areas with a larger number of ethnic minorities than other areas in People’s Republic of China. The unique socioeconomic, historical background, traditional culture, lifestyle habits, and geographic environment in ethnic minority autonomous regions suggest that the DPR may differ from other parts of People’s Republic of China. Furthermore, the unique setting of this autonomous region and the high degree of mistrust and tension between doctors and patients presents some difficulties in applying conventional models of the DPR. The closest approach is to consider the relationship one of mutual participation, in which the relationship is held to be mutually beneficial. This study, therefore, was conducted to understand the perception of DPR from the doctor and patient side, to compare the perception of DPR in provincial and city hospitals and to explore the factors associated with the perception of DPR in Inner Mongolia.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a cross-sectional study undertaken in one provincial level and one city-level general public hospital in Hohhot city, the capital of the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China.

Study protocol

The study protocol was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University (REC Number: 58-266-18-5). Furthermore, this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Permission and support were obtained from the two survey hospitals. Before the survey, objectives and benefits of this study were explained verbally and in written form attached to the questionnaire for the doctors and patients. Written informed consent was obtained from all those who agreed to participate in the study prior to conducting the interviews. For the participants under the age of 18 years, their parental informed consent was obtained before being enrolled in the study.

Study population

All doctors who were working in the selected hospital clinic for at least 6 months were eligible for the study. The doctors who were re-hired after retirement were excluded in this study because their workload was significantly lower than that of the formal doctors. In each hospital, the personnel office was requested to make a list of all doctors before selection. Doctors were chosen based on a systematic sampling of eligible doctors from each department. In practice, if a selected doctor in the list was not available to answer the questionnaire then another doctor in the same clinic was randomly chosen as a replacement.

Patients were approached after they had exited from the doctors’ consultation rooms. All patients aged 16 years of more were eligible for the study. Patients who were unable to communicate, read, or write in the local language were excluded. Systematic sampling of every fifth patient who exited from the doctor’s consultation rooms was employed. Patients that met the inclusion criteria were approached, greeted, and invited to participate in the survey after receiving explanation information about the study. If a patient did not meet the inclusion criteria or declined to participate, the immediate next patient was invited to participate instead. Patients who consented to participate were asked to complete a structured questionnaire at that time. Patients were told that their responses would be anonymous.

Survey instruments

Doctor’s questionnaire

A self-administered questionnaire covering three aspects was used for the doctors. The first part included items on sociodemographic factors, such as gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, household income, income satisfaction, insurance status, and the clinic or department where the doctor worked. These included Internal Medicine department (Cardiology, Respiratory, Digestive, Endocrinology, Nephrology, Neurology, Gerontology, Haematology, and Oncology), Surgery department (General surgery, Hepatobiliary surgery, Urology, Thoracic surgery, Emergency surgery, Spine surgery, Neurosurgery, Gastrointestinal surgery, Tumour surgery), Gynaecology, Obstetrics, Paediatrics, Ear-nose-throat, Traditional Chinese Medicine, Rehabilitation, Laboratory Medicine, Reproductive Medicine department, Emergency Department, and Medical Services. The second part included the Difficult Doctor–Patient Relationship Questionnaire (DDPRQ-10),16 which has been used in emergency and primary care17,18 and in previous research.14,19 “Difficult” in this context refers to the doctor’s perception of a subjective difficulty when caring for their patients. There are five items in the DDPRQ-10 assessing the doctor’s subjective experience (for example, “Do you find yourself secretly hoping that this patient will not return?”). Four questions are quasi-objective items in regard to the patient’s behavior, such as “How time-consuming is caring for this patient?” One item that refers to symptoms combines elements of the patient’s behavior and of the physician’s subjective response (“To what extent are you frustrated by your patients’ vague complaints?”). Each item is scored from 1 (not at all) to 6 (a great deal). A total score is produced by summing ratings across all 10 items to give an overall score ranging from 10 to 60, with higher scores indicating a more difficult DPR. The third part included questions referring to factors of DPR reported in previous studies. A question designed to measure the negative influence of media was: “How often have you been affected by negative media coverage of DPR?” for which the options for response were “never”, “sometimes”, and “often”. A question that aimed to measure trust between doctors and patients from the doctor side was: “What is the degree of trust you feel from your patients?” with the response options of “low”, “fair”, and “high”, but collapsed into two levels in the analysis: high level (high) and low level (low or fair). Another question aimed to estimate a defensive practice of medicine:

In consideration of the tensions between doctors and patients, do you prescribe procedures or diagnostic tests or drugs that are clinically unnecessary to avoid possible troubles (such as lawsuits and disputes)?

This question was included because some doctors had reported that they had to have some defensive behaviors (such as prescribing diagnostic tests or drugs or medical procedures) as evidence in addressing patients’ possible queries.20 Doctors were also asked to report the number of medical disputes they had encountered with patients over the previous 12 months. Those who had experienced medical disputes were then asked to state the three most common types.

Patient self-report measures

From the patients’ perspective, the quality of the DPR was assessed using the Patient–Doctor Relationship Questionnaire (PDRQ-9). The PDRQ-9 was derived from the Helping Alliance Questionnaire by Lubursky and has been used for scientific purposes and in practice to monitor the patient–doctor relationship in primary care settings.21 Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very low quality) to 5 (very high quality). Items scores are summed to give an overall score ranging from 9 to 45.

In the patient questionnaire, an additional question which aimed to measure the negative influence of media was “How often have you been affected by negative media coverage concerning the doctor–patient relationship?” with options for response being “Never”, “Sometimes”, and “Often”. The question that aimed to measure trust between doctors and patients from the patient’s perspective was: “What is the degree of trust you feel in your doctor?” with options for response being “Low”, “Fair”, and “High”.

Data collection

A 2-day training course which included a workshop on data collection was provided for all research assistants before the data collection. This training aimed to ensure that all assistants fully understood their respective roles and responsibilities. To evaluate the interpretability and understanding of items by the participants, a pilot study was conducted in a non-study hospital to test the questionnaire and finalize the tools for quality assurance.

For the main study, patients’ and doctors’ data were collected during May 8–June 24, 2016. Both interviewer-administered and self-administered questionnaires were used in this part. The interviewer-administered questionnaire was used for some elderly patients who could communicate well but had literacy difficulties. The participating patients were asked to complete measurements immediately after a consultation. However, to avoid affecting doctors’ work, the participating doctors were required to answer the questionnaires after they finished a day’s work.

The sample size calculation was based on the previous literature and the objectives of the study. To identify factors related to the DPR among doctors, we assumed the prevalence of any factor to range from 10% to 90% and a power of 80% to detect a difference in DDPRQ-10 score of at least 0.9 standard deviations as statistically significant at a type I error probability of 0.05, requiring a sample size from each hospital of 109 doctors. Considering a response rate of 95%, the number of doctors that needed to be approached was calculated to be 115 doctors from each of the provincial-level and city-level hospitals.

For patients, to identify factors related to the DPR, we assumed the prevalence of any factor to range from 10% to 90% and a power of 80% to detect a difference of at least 0.6 standard deviations as statistically significant at a type I error probability of 0.05, a sample size of 290 patients would be required from each of the provincial and city-level hospitals. Considering a response rate of 90%, the actual number of patients that needed to be approached was increased to at least 323 in each hospital.

Data analysis

Data from the doctors’ and patients’ questionnaires were double-entered into a database using EpiData version 3.1. R and Stata statistical software were used to analyze the data (R version 3.3.2, R Core Team, Vienna, and Stata version 14.1, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Directed acyclic graphs (DAG) were created to represent the potential causal relationships between all relevant variables and the outcomes, DDPRQ-10, and PDRQ-9 (DAGitty Version 1.1, Johannes Textor, Utrecht University, NL, USA). Chi-square tests, independent sample t-tests, and analysis of variance were used to compare categorical and normally distributed continuous variables, respectively, between groups, while the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare non-normally distributed variables. Multivariate linear regression was used to identify the magnitude of associations conditioning by assessing coefficients of total effect and their 95% confidence interval on appropriate sets of adjustment variables as indicated by the DAG.

For each independent variable, covariates were selected for inclusion in the models based on a DAG. The following variables were considered in the context of doctors’ DAG: hospital level, department, sex, age, education, technical title, weekly work time, income, income satisfaction, coordination, hospital environment, media influence, frequency of medical dispute, ethnicity, number of patient per day, defensive behavior, pressure, degree of trust. Potential relationships between the outcome DDPRQ-10 and other variables were assigned based on knowledge of the literature and an understanding of their possible relationships (Figure S1). The factors considered in the context of the patients’ DAG were: hospital level, ethnicity, income satisfaction, waiting time, consultation time with the doctor, the expectation of treatment result, trust in the doctor, hospital environment, and media influence. Relationships between the outcome PDRQ-9 and other variables were assigned based on knowledge of the literature and an understanding of their possible relationships (Figure S2).

Potential confounder variables for the total effect of each independent variable or confounder and intermediate variables for the direct effect were identified from the DAG to minimize bias in the estimated coefficients.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of doctors

A total of 240 questionnaires were sent out for doctors. A total of 229 were returned and 226 were valid. The response rate was 95.4%. The majority (52.7%) were male, aged 30–40, married, had a master’s degree, and belonged to the Han ethnic group. The majority (92.5%) worked more than 40 hrs per week, met no <30 patients per day (58.1%), and felt pressure from work (75.2%). Most doctors had a good coordination with their colleagues, but the feeling of trust from their patients was not high. Most doctors were influenced by the negative media. Most had defensive behaviors, thought the hospital environment was not good, and had a history of medical disputes.

DDPRQ-10

The DDPRQ-10 scores ranged from 14 to 48 (mean=32.85; SD=6.07). As shown in Table 1, doctors from the provincial hospital had a higher mean DDPRQ-10 score than those from the city hospital (P=0.039). Doctors who worked in Internal Medicine clinics also had a higher DDPRQ-10 score on average compared to doctors who worked in other clinics (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of doctors and univariate analysis of DDPRQ-10 scores |

There were no significant differences in DDPRQ-10 scores according to sex, ethnicity, or marital status, but the doctors aged 31–40 reported higher scores on average than doctors aged 30 or less. Doctors who had a master’s degree had higher scores on average than doctors who had a lower level degree.

For work-related variables, there were no significant differences in DDPRQ-10 scores by technical title, income, weekly work time, level of coordination with colleagues, or the number of patients seen per day. However, doctors who were satisfied with their income, considered the hospital environment to be good, did not feel pressure, or felt trust from their patients had lower DDPRQ-10 scores. Doctors who were often affected by the negative media coverage, having a previous experience of medical disputes, or often prescribed unnecessary diagnostic tests, drugs, or medical procedures, reported higher DDPRQ-10 scores.

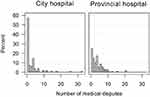

This study showed that more than half of the doctors (59.3%) had been involved in at least one medical dispute at their work during the past year. Doctors from the provincial hospital were more prone to medical disputes, with 42.2% having experienced 1–3 incidents, 19.0% 4–6 disputes, and 13.8% seven or more medical disputes in the previous year. Verbal conflicts with patients were the most frequently reported (n=434), followed by patients complaining to the health administration or hospital (n=138). Thirty doctors (13.3%) had experienced a physical assault over the past 12 months. However, medical malpractice litigation was less common – only 14 cases were reported. Figure 1 shows the percentage of doctors having medical disputes in the previous year by hospital level. The percentage of doctors in the provincial level hospital (75.0%) was higher compared to that of doctors in the city-level hospital (42.7%).

|

Figure 1 Percentage of doctors having medical disputes in the previous year by hospital level. |

Sociodemographic characteristics of patients

A total of 713 patients participated in the study and returned the questionnaires. The response rate was 90.2%. The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 2. The majority were female, aged <30 years, married, belonged to the Han ethnic group, and had medical insurance. Waiting times were <1 hr for half of the patients and doctor consultation times ranged from 1 to 60 mins. The level of medical knowledge was average and most had a high expectation of treatment results. Most had a high level of trust in their doctor and thought the hospital environment was good.

|

Table 2 Demographic characteristics of patients and univariate analysis of PDR-9 scores |

PDRQ-9

PDRQ-9 scores ranged from 9 to 45 (mean=31.36; SD=7.56). The mean PDRQ-9 score of patients at the province hospital was lower than that for the city hospital (p=0.025) (Table 2). Patients of Han ethnicity had a higher PDRQ-9 score than those of Mongolian ethnicity. Patients who were satisfied with their household income reported higher PDRQ-9 scores than those who were not. Longer waiting times correlated with lower PDRQ-9 scores, while patients who spent <5 mins consulting the doctor reported lower PDPRQ-9 scores on average than patients who spent longer than 5 mins. Patients who considered the hospital environment to be good, or had a high degree of trust in doctors reported higher PDRQ-9 scores. Patients who were often influenced by negative media coverage reported a lower PDRQ-9 score compared to those who reported being less frequently influenced.

Factors associated with DPR from the doctors’ perspective

Results of the regression modeling are shown in Table 3. Based on multiple linear regression analyses, 12 predictors of DDPRQ-10 were identified. Provincial level doctors had on average a 1.66 (95% CI=0.08–3.24) higher score compared to city-level doctors (p=0.039). Significantly higher scores were also found for doctors aged 31–40 years, working in the Internal Medicine department, having a master’s degree, being dissatisfied with their income, considering the hospital environment to be bad, being often affected by the negative media, working more than 40 hrs per week, suffering pressure, and having defensive behaviors.

|

Table 3 Adjusted coefficients for DDPRQ-10 scores from linear regression |

Results showed the total effect of long working hours (coefficient 3.49; 95% CI=0.01, 6.97) was greater than the direct effect (coefficient=1.28; 95% CI=−2.27, 4.83), indicating that much of the total effect of longer working hours may be mediated through its association with the intermediate of pressure of work. Similarly, the total effect of increased difficulty reported by doctors in the provincial hospital (coefficient=1.66; 95% CI=0.08, 3.24 compared with the direct effect −0.62; 95% CI=−3.01, 1.77) is likely to be mediated via the associations with poorer perception of hospital environment and larger number of patients per day; and that of increased frequency of negative media influence (4.21; 95% CI, 1.21, 7.21 compared with the direct effect 0.86; 95% CI=−2.98, 4.69) to be mediated via its associations with the greater tendency to make unnecessary prescriptions, the feeling of pressure and the perception of a low level of trust between doctors and patients. The apparent differences between the total and direct effect of a masters’ degree could not be explained by any of the intermediates indicated in the causal graph.

Factors associated with DPR from the patients’ perspective

Based on the multivariate analysis, nine variables were found to be significantly associated with PDRQ-9 (Table 4). Patients from the provincial level hospital had on average a −1.28 coefficient (95% CI, −2.39, −0.17) lower PDRQ-9 score compared to city-level patients (p=0.024). Significantly lower PDRQ-9 scores were also seen for Mongolian patients, patients who were dissatisfied with their income, longer waiting time, shorter consultation time with doctors, lower expectation of treatment result, low level of trust in the doctor, poor hospital environment, and more frequent negative media influence. When the effect of hospital level on patient satisfaction via the pathways of waiting time and consultation time was examined, the coefficient decreased from −1.28 to −2.16 indicating a major contribution of waiting and consultation times to the poorer satisfaction of outpatients in the provincial hospital.

|

Table 4 Adjusted coefficients for PDRQ-9 scores from linear regression |

Discussion

This cross-sectional study conducted in one provincial and one city-level hospital of Hohhot explored the quality of the DPR and its associated factors from the doctors’ and outpatients’ perspective in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of People’s Republic of China. In this study, the provincial hospital sample was located in urban area of the city, which has 52 clinical medical departments, 1,891 open beds, and 2,973 employees, and sees 2.4 million outpatients per year, whereas the city hospital sample was adjacent to the suburb and rural area of the city, which has 48 clinical medical departments, 1,000 open beds, and 1,800 employees, and sees 700 thousand outpatients per year. These are two very representative samples in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Most of the provinces in People’s Republic of China have these two level hospitals and the classification of hospital grades is based on uniform national standards. Nevertheless, while the findings are considered well representative of the unique setting of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region including both urban and rural areas, the applicability to other areas of People’s Republic of China may need to be confirmed in further studies.

The frequency of medical disputes in these two hospitals was high, particularly among doctors in the provincial level hospital. More than half of the doctors had experienced at least one medical dispute with their patients over the past 12 months. The practical form of disputes varied from official complaints to physical violence. Medical malpractice litigation was rare. These results are similar to those from Shenzhen city’s investigation in Guangdong province of People’s Republic of China, which showed that 44.8% of the physicians had experienced some form of medical conflict in the previous year.6

Another finding was that, after adjusting for other factors, the DPR was significantly associated with hospital level, negative media influence, income satisfaction, and hospital environment from the perspectives of both doctors and patients. From the doctors’ perspective, those working in the provincial hospital reported a significantly more difficult DPR than doctors in the city hospital. Similarly, patients attending the provincial hospital reported a significantly lower quality DPR than patients attending the city hospital. Moreover, the percentage of frequency of medical disputes reported from provincial doctors (75.0%) was significantly higher than the number from city hospital (42.7%). Similar results22 showed that the level of harmony in the DPR was low in People’s Republic of China, and the medical staff from a high-level hospital had a worse DPR compared with those from a low-level hospital. In this study, comparing the total and direct effects of level of hospital on patient satisfaction suggests that long waiting time and short consultation time in the provincial hospital are important intermediates in the pathway whereby hospital level affects outpatient satisfaction. The average daily number of outpatients per doctor at the provincial hospital in our study is approximately 95, while that in city hospital is about 40. This means that the doctors in the provincial hospital can offer an average of 3–5 mins consultation time for each patient. Morrell23 indicated that the patients were less satisfied with the consultation if the doctors spent less time with the patients. Hence, it is reasonable that the DPR in the provincial hospital was worse than that in the city hospital. The results of this study also demonstrate that long waiting times and the shorter consultation times with the doctor were predictors of worse DPR from the patients’ perspective. Cape24 and Mohd25 also found that waiting time is an important factor related to patient satisfaction and short contact time spent with the doctor is a common source of patient dissatisfaction with the consultation process.

Negative media influence was found to be a significant factor contributing to the tense DPR from both doctors’ and patients’ perspectives. This result is consistent with two previous studies which reported that both doctors and patients considered that mass media, in addition to the health care system, was the main factor affecting the DPR.15,26 Nowadays, the Chinese media play an important role in the coverage of the DPR, possibly stimulating tension between them.27 Media reports excessively highlight the “tension, opposition and conflict” in the DPR, which can damage the trust between doctors and patients, and intensify people’s hostility toward medical staff.28 Similar to findings from other studies,29,30 our study shows that dissatisfaction with income, among both doctors and patients, was associated with worse perceptions of the DPR. Moreover, the perception of a better hospital environment was associated with better DPR. Cai and other researchers found that uncaring attitudes, poor facilities, inflated medical bills, and cumbersome procedures were among the major complaints of hospital inpatients.31

No differences across clinic type were found in the quality of DPR from the perspective of the patients, but doctors working in the Internal Medicine department had worse perceptions compared to other departments. By contrast, He6 reported that surgery departments were more prone to medical disputes from doctors’ perspectives in Shenzhen, a city in the south of People’s Republic of China. However, many socioeconomic characteristics differ between regions of People’s Republic of China including aspects of payment of medical fees, availability of medical equipment, and human resources for health. In particular, some ethnic minority areas located in the northwest of People’s Republic of China have a relatively backward economic development and differences in factors influencing the DPR are not unexpected.

Doctors aged between 31 and 40 and holding a master’s degree perceived that their patients were more difficult than doctors with a bachelor’s degree, a result that contrasts with a study by another researcher,32 who reported that while doctors’ and patients’ education level had an influence on the DPR, age had no effect. Our study also showed that doctors who worked more than 40 hrs per week and felt pressure perceived that the relationship with their patients was more difficult. Similarly, some researchers found that higher workloads resulted in doctors behaving more defensively, which is consistent with parts of our findings.6 In our study, 76.1% of doctors reported that they sometimes prescribed unnecessary procedures or diagnostic tests or drugs to avoid possible troubles later. Furthermore, those doctors who had defensive behaviors reported more difficult patients compared with the doctors who never had defensive behaviors. However, a tense DPR could, in turn, give rise to defensive behaviors, as has been reported by other researchers,6 thus forming a vicious cycle.

In this study, from the patient’s perspective, Mongolian ethnicity was associated with a lower DPR. One possible reason is that most of the doctors in the study hospitals were of Han ethnicity and could not speak the Mongolian language. Therefore, compared to the Han patients, Mongolian patients may have experienced a poorer communication and therefore perceived a poorer DPR. Similar results were found in a study by Ferguson, where race, ethnicity, and language had a substantial influence on the quality of the DPR.33 In contrast with a previous study,20 which reported that patients’ higher expectation was the major reason for a worse DPR in the opinion of doctors, our study showed that high patient expectation was associated with better DPR indicating that there are obvious differences between doctors and patients in the perception of the DPR. Furthermore, the results of this study uncovered that a low degree of trust is one factor that causes tension between doctors and patients. According to Hsiao, over-prescription accounts for more than one-third of all pharmaceutical expenditure.34 It is also common for medical staff in People’s Republic of China to be given “red envelopes” (cash bribes) from patients.35 Such a monetary relationship is somewhat incompatible with the development of a trusting relationship between doctors and patients. Building an environment of trust between the doctors and patients should be a priority of the health services in People’s Republic of China.

Compared with other previous studies, the main strength of this study is the use of standard questionnaires, which included multiple aspects of the DPR to evaluate the DPR as the outcome, for the doctors and patients. The use of a standard questionnaire increased the reliability and validity of the assessment of the DPR. Secondly, multivariate modeling was used to detect factors influencing DPR in which confounding was controlled for appropriately. The third strength of this study is the use of DAG to specify causal pathways and estimate associations with minimum bias.36

This study, however, has some limitations. Firstly, there were some sensitive questions in the doctors’ questionnaire such as the items on doctors’ income and defensive practices. In particular, the question on defensive practice is likely to be under- rather than over-reported by doctors. Their aberrant behavior could be a motivation for misreporting. Thus, respondents’ unwillingness to uncover their actual behaviors has the potential to introduce bias. In order to reduce such bias, we phrased this question, as done in a previous study,6 in such a way as to minimize its sensitivity and to be acceptable to the doctors in our study. At least our study can obtain a minimum estimation of the prevalence of doctors’ defensive practices. Furthermore, we maintained anonymity and used volunteer interviewers rather than administrative staff members at the hospital to distribute and collect the questionnaires in the expectation that this would encourage the doctors to answer the questionnaire truthfully. A second limitation is that only quantitative data were collected in this study. In order to better understand the viewpoint of the DPR from the doctors’ and patients’ perspectives, qualitative studies including in-depth interviews, which can explore the culture-specific issues in greater depth, should be undertaken. Thirdly, this study only explored factors influencing the DPR from doctors’ and patients’ perspectives. There was no attempt at exploring the implications of the various levels of satisfaction reported by either patients or doctors. Further study should consider more questions, such as effect on drug compliance and on symptom relief, that may be making a more meaningful and valuable study. Lastly, in this study, there were some replacements for doctor non-responders. It is possible that the replacements may have differed somewhat from the non-responders. However, the number was very low and unlikely to substantially affect the overall findings.

Conclusion

Using a cross-sectional study in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of People’s Republic of China, provincial hospital type, income dissatisfaction, perception of poor hospital environment, and negative media influence were strongly associated with perceived poor quality of the DPR by both doctors and patients. Additional factors from the doctors’ side were Internal Medicine clinics, mid-age of doctors, mid-level education, long weekly hours, a feeling of pressure, and the practice of defensive behaviors. From the patients’ side, additional factors were Mongolian ethnicity, long waiting time, short consultation time with doctors, low expectation of the treatment result, and lower degree of trust in the doctor. Therefore, enhancing the income satisfaction through rational salary reward system, improving hospital environment, and reducing negative media reports are potential ways to improve the DPR from both doctors and patients perspectives. Reducing doctors’ workload, relieving their pressure of work, controlling their defensive behaviors, finding ways to solve the problems of long waiting time and short consultation time for patients, and fostering a higher degree of patients’ trust in the doctor, should also contribute to an improvement in the DPR. The study may provide a useful basis on which health policy makers and administrators could formulate policy changes and develop strategies to reduce the problem of the tense DPR in Chinese hospitals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Key Research Base of Humanities and Social Science of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the administrators and doctors of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region People’s Hospital and the First Hohhot Hospital for coordination of the survey. Our thanks are also expressed to all patients who participated in this study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Park K. Park’s Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine. 18th Edition, Banarsidas Bhanot Publishers, Jabalpur. 2007.

2. Lejoyeux M. The doctor-patient relationship: new psychological models. Bull Acad Natl Med. 2011;195(7):

3. Banerjee A, Sanyal D. Dynamics of doctor-patient relationship: a cross-sectional study on concordance, trust, and patient enablement. J Family Community Med. 2012;19(1):12–19. doi:10.4103/2230-8229.94006

4. Werther J. Focus on doctor-patient relationship the secret to practice success. Tenn Med. 2010;103(10):9.

5. Mendoza MD, Smith S, Eder M, Hickner J. The seventh element of quality: the doctor-patient relationship. Family Med Kansas City. 2011;43(2):83.

6. He AJ. The doctor–patient relationship, defensive medicine and overprescription in Chinese public hospitals: evidence from a cross-sectional survey in Shenzhen city. Soc Sci Med. 2014;123:64–71. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.055

7. Zhang X, Sleeboom-Faulkner M. Tensions between medical professionals and patients in mainland China. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2011;20(03):458–465. doi:10.1017/S0963180111000144

8. Lancet T. Violence against doctors: why China? Why now? What next? Lancet. 2014;383(9922):1013. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60501-8

9. Hou X, Xiao L. An analysis of the changing doctor-patient relationship in China. J Int Bioethique Ethique. 2012;23(2):83–94.

10. Lancet T. Ending Violence against Doctors in China. The Lancet. 2012;373(9828):1764. doi:10.1016/S0140_6736(12)60729_6

11. Jie L. New generations of Chinese doctors face crisis. Lancet. 2012;379(9829):1878. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60774-0

12. Li J, Qi F, Guo S, Peng P, Zhang M. Absence of humanities in China’s medical education system. Lancet. 2012;380(9842):648. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61368-3

13. Jagosh J, Boudreau JD, Steinert Y, MacDonald ME, Ingram L. The importance of physician listening from the patients’ perspective: enhancing diagnosis, healing, and the doctor–patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(3):369–374. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.028

14. Wu H, Zhao X, Fritzsche K, et al. Quality of doctor–patient relationship in patients with high somatic symptom severity in China. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23(1):23–31. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2014.12.006

15. Le H, Wei J, Xiang X. Study on cognitive differences between doctors and patients of doctor-patient relationship. Chin Hosp Manage. 2011;31(1):15–17.

16. Hahn SR, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, et al. The difficult patient. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11(1):1–8. doi:10.1007/bf02603477

17. Maunder RG, Panzer A, Viljoen M, Owen J, Human S, Hunter JJ. Physicians’ difficulty with emergency department patients is related to patients’ attachment style. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(2):552–562. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.001

18. Walker EA, Katon WJ, Keegan D, Gardner G, Sullivan M. Predictors of physician frustration in the care of patients with rheumatological complaints. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19(5):315–323.

19. Jackson JL, O’Malley PG, Kroenke K. A psychometric comparison of military and civilian medical practices. Mil Med. 1999;164(2):112.

20. Pan C, Wang J. Investigation on recognition diversity between doctors and patients on doctor-patient relationship. Med Philos. 2005;26:63–64.

21. Lubursky L, Barber J, Siqueland L, Johnson S. The revised helping alliance questionnaire (HAQ-II). J Psychother Pract Res. 1996;5:260–271.

22. Liu L, Xie Z, Qiu Z. Doctor-patient relationship in different level hospitals and influencing factors from doctor side. Med Philos. 2009;8:014.

23. Morrell D, Evans M, Morris R, Roland M. The “five minute” consultation: effect of time constraint on clinical content and patient satisfaction. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292(6524):870–873. doi:10.1136/bmj.292.6524.870

24. Cape J. Consultation length, patient-estimated consultation length, and satisfaction with the consultation. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(485):1004–1006.

25. Mohd A, Chakravarty A. Patient satisfaction with services of the outpatient department. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014;70(3):237–242. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2013.06.010

26. Shu Y, Peng Z, Xue M, Li Y. Surveying the cognition on doctor-patient relationship in different views from patients and medical staffs and its countermeasures. Chin Health Serv Manage. 2013;3:178–180.

27. Gao J, Li E, Wang X, Liang L, Wu L. Media factors affecting current physician-patient relationship and countermeasure research. Chin Med Ethics. 2009;4:007.

28. Xie J, Zhang Y. Effect of media public opinion on building a harmonious doctor-patient relationship. China Health Ind. 2015;33(1):1–3.

29. Cheng Z, Wang J, Liu X. The key influencing factor of doctor-patient relationship: interest demand of patients. ACTA Univ Med Nanjing(Social Sciences). 2014;61(2):121–124.

30. Ma L, Su W. Analysis of the countermeasures and awareness of the doctor-patient relationship. Mod Prev Med. 2011;10:029.

31. Cai M, Zhang Y. Inpatients’ evaluation of the health institution and factors associate with patients’ dissatisfaction. J Chin Hosp Manage. 2010;30(5):7–9.

32. Deng F. Factor influencing the doctor-patient relationship: a case study of a public hospital in Changsha. Pract Prev Med. 2010;17(1):182–183.

33. Ferguson WJ, Candib LM. Culture, Language, and the Doctor-Patient Relationship. Fam Med. 2002;34(5):353–361.

34. Hsiao WC. When incentives and professionalism collide. Health Aff. 2008;27(4):949–951. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.949

35. Lancet T. Chinese doctors are under threat. Lancet. 2010;376(9742):657. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61315-3

36. Shrier I, Platt RW. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):70. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-8-70

Supplementary materials

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.