Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 13

Factors affecting hypertensive patients’ compliance with healthy lifestyle

Authors Alefan Q , Huwari D, Alshogran OY , Jarrah MI

Received 16 December 2018

Accepted for publication 12 March 2019

Published 23 April 2019 Volume 2019:13 Pages 577—585

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S198446

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Qais Alefan,1 Dima Huwari,1 Osama Y Alshogran,1 Mohamad I Jarrah2

1Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan; 2Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan

Purpose: This study aimed to identify factors correlating with hypertensive patients’ compliance with lifestyle recommendations in north of Jordan.

Patients and methods: A cross-sectional survey and face-to-face interview methods were used to collect the data from 1000 adult Jordanian hypertensive patients (>18 years old). A questionnaire was developed based on previous literature and professional consultation.

Results: Only 23% of the patients were fully compliant with healthy lifestyle behaviors. About 95% were knowledgeable on hypertension and 86% had positive beliefs about the management protocols of their disease. Gender, physician counseling on a healthy lifestyle, patients’ beliefs about hypertension management, and their knowledge on hypertension and its management have an independent effect on compliance with lifestyle recommendations.

Conclusion: Patients’ compliance with lifestyle recommendations was low. Receiving counseling from physicians about healthy lifestyle and self-care; being informed about hypertension and its management; and having positive beliefs about managing this disease are significant predictors of patients’ compliance with lifestyle recommendations.

Keywords: blood pressure, adherence, diet, exercise

Introduction

Hypertension, also called high blood pressure (BP), is a chronic disease that is defined as persistently elevated arterial BP.1–3 Hypertension is divided into primary hypertension, also called essential hypertension (90%) which results from unknown pathophysiologic etiology and has no cure; and secondary hypertension (10%) which results from specific causes such as chronic kidney disease, Cushing syndrome, hyperparathyroidism, primary aldosteronism, hyperthyroidism, and some medications (eg, corticosteroids, estrogens, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, amphetamines, cyclosporine, erythropoietin, venlafaxine). Secondary hypertension can be mitigated or potentially cured.3,4 Elevated BP is a major risk factor for cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, kidney, and eye diseases.1

Around the world, the overall prevalence of raised BP in adults 18 years or older was nearly 22% in 2014. Within the World Health Organization (WHO) regions, the prevalence of elevated BP was the lowest in the USA (18%). The highest prevalence of elevated BP was in Africa (30%). In the Eastern Mediterranean countries, it was around 27% for both sexes. In all WHO regions, men have a slightly higher prevalence of elevated BP than women. Based on income levels, the prevalence was lower in middle-income and high-income countries compared to low-income countries.5,6

According to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) guidelines for the management of hypertension, hypertensive patients aged 60 years or older should be treated to a BP goal of less than 150/90 mmHg and hypertensive patients 30 through 59 years of age to a BP goal of less than 140/90 mmHg. The same goals are recommended for hypertensive adults with diabetes or chronic kidney disease as for the general hypertensive population younger than 60 years.1

Lifestyle changes can be used as an initial treatment before the start of antihypertensive medications and as an adjunct to medications in persons already on drug therapy. Lifestyle changes include weight loss if overweight; adoption of the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension eating plan; dietary sodium restriction; moderate alcohol consumption; regular aerobic physical activity; smoking cessation; and stress reduction.3,7–9

Over the past decade, the prevalence of hypertension has significantly increased in Jordan. Between 1994 and 2009, the prevalence rate increased from 29% to 32%. The prevalence was higher among males, elderly, least educated, obese, and diabetic patients than their counterparts. A large number of hypertensive patients in Jordan have uncontrolled BP.3,10

The main aims of the study were to estimate the rate of compliance with lifestyle change recommendations; assess the extent of patients’ knowledge and beliefs about hypertension; and identify factors correlating with hypertensive patients’ compliance with lifestyle recommendations in the north of Jordan.

Materials and methods

This was a cross-sectional survey which was conducted in between October 2016 and December 2016. A total of 1000 adult Jordanian patients (>18 years old) with hypertension, defined as a systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg; diagnosed for at least 1 month; on antihypertensive drugs; and attending the hypertensive clinic in King Abdullah University Hospital (KAUH), were randomly selected and included in this study. Based on previous literature on the prevalence of hypertension in Jordan which indicated that about one-third of adult Jordanians are affected with hypertension, 0.05 margin of error, and confidence interval of 95%, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be 385. However, we recruited more participants to avoid missing information that may result from incomplete responses.

The study was conducted at KAUH. KAUH was built within the Jordan University of Science and Technology campus, which is located in the north of Jordan, on the highway linking Jordan to Syria. It is about 20 km east of Irbid and 80 km north of Amman. This carefully chosen location allows the hospital to provide primary, secondary, and tertiary health-care services to more than 1 million inhabitants of Irbid, Ajloun, Jarash, and Mafraq governorates, in particular, and to all of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan population in general. The hospital bed capacity is 683 beds, which can be increased to 800 beds in any emergent situation. In addition, it is a training hospital that provides training for junior medical doctors and pharmacists.11

The institutional review board of KAUH, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan, approved the study protocol before implementation.

The study was conducted according to the criteria set by the declaration of Helsinki, and each subject signed an informed consent before participating in the study. Patients were interviewed by a trained pharmacist using a standard questionnaire to obtain data related to their sociodemographic and medical characteristics, general behaviors, counseling on lifestyle behaviors and self-care, and knowledge and beliefs about hypertension. The interview was administered in 10–15 min. The questionnaire was developed based on previous literature12–22 and with the help of experts in the field of hypertension. The developed questionnaire was piloted with 20 patients. Their comments on the questionnaire were taken into consideration and were discussed by the research team.

Study measures

The outcome variable of the study was health behaviors. Independent variables in this study were distributed into four parts:

- Socio-demographics and medical characteristics: age, gender, family status, education, country of origin, place of residence, presence of maids, education level, monthly income, height, weight, BMI, level of blood pressure, time since hypertension diagnosis, and medication use.

- Counseling on lifestyle behaviors and self-care: appropriate diet, physical activity, smoking cessation, body weight, self-measurement of blood pressure, risks and complications of hypertension, and signs of deterioration in the patient’s health status.

- Knowledge about hypertension.

- Beliefs about hypertension management.

Every patient was given a score12,14,17,18 based on his/her answers to the following parts:

- Lifestyle and self-management counseling (seven questions): Patients who answered (yes) to 0–4 items were scored as (low) in this measure, whereas who answered (yes) to more than four items were scored as (high).

- Knowledge on hypertension (five questions): Patients with 3–5 correct answers (“True” for the first four questions and “False” for the last question) were scored as (high) in this measure, whereas those with 0–2 correct answers were scored as (low).

- Beliefs about hypertension management (four questions): Patients with 3–4 correct answers (“Agree”) were scored as (high) in this measure, whereas those with 0–2 correct answers were scored as (low).

- General behavior (physical activity, diet, and smoking status): Patients who reported a full adherence to healthy behaviors (exercise regularly, have never smoked or used to smoke, and follow a diet for hypertension) were defined as (compliant).

Then, based on their answers on the general behaviors questions and based on their scores, in all parts, patients were divided into compliant and non-compliant groups.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS® Version 23. Descriptive statistics were calculated, and chi-square tests were conducted to find bivariate correlations with the outcome variables. All variables significant at the p<0.05 level were entered into the binary logistic regression model as potential predictors of adherence to lifestyle recommendations.

Results

A total of 1000 patients were interviewed, and all provided complete responses. Table 1 shows that 48% (n=480) of the sample were over 60 years and more than half (n=570, 57%) were female. About two-thirds (n=630, 63%) were city residents, and the majority (n=900, 90%) were married. Only one-third (n=340, 34%) of respondents completed tertiary education, and a majority (n=920, 92%) reported that they do not have maids in their homes. A majority of respondents (n=800, 80%) were either overweight (n=350, 35%) or obese (n=450, 45%). Slightly more than half of the patients (n=530, 53%) reported that their BP was less than 140/90 mmHg at the last measurement, and half (n=490, 49%) reported that their BP was controlled (Table 1).

| Table 1 Sociodemographic and medical characteristics of patients |

A majority of respondents received counselling on physical exercise (n=690, 69%), on desirable weight (n=700, 70%), and on diet (n=770, 77%). However, less than half (n=430, 43%) received counseling on smoking cessation. Also, about two-thirds received education on complications of high BP and signs of deterioration (n=580, 58%) and (n=630, 63%), respectively, while less than half received education on how to measure BP (n=470, 47%) (Table 2).

| Table 2 Patients’ reports on lifestyle and self-management counseling |

Less than half (n=470, 47%) of the patients exercise regularly and more than half never smoked (n=590, 59%) and adhere to a special diet (n=580, 58%) (Table 3).

| Table 3 Patients’ reports on general behaviors |

The majority of the patients responded with “True” to the following statements “unbalanced BP can damage blood vessels and lead to heart attacks and strokes” (n=920, 92%); “being overweight does affect BP” (n=940, 94%); and “salt consumption raises BP” (n=970, 97%); “physical exercise helps reduce blood pressure” (n=890, 89%); and that “medication is not the only modality needed to treat hypertension” (n=830, 83%) (Table 4).

| Table 4 Patients’ knowledge about hypertension |

Most of the patients agreed that antihypertensive medications help them to feel better (n=920, 92%), a diet to reduce hypertension will help them feel better (n=810, 81%), they should be treated constantly (n=880, 88%), and that it is possible to control their blood pressure (n=730, 73%). Also, more than half (n=540, 54%) of the patients reported that ensuring a balanced BP is their responsibility (Table 5).

| Table 5 Patients’ beliefs about hypertension |

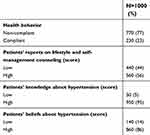

It was found that only 23% of the patients were adherent to health behaviors, whereas (77%) were not, and most of the patients (n=560, 56%, n=950, 95%, n=860, 86%) got high scores in counseling, knowledge, and beliefs about hypertension parts, respectively (Table 6).

| Table 6 Overall patients’ scores |

From the results of chi-square tests, significant associations were found between compliance and gender (χ2= 10.499, p=0.001), work status (χ2= 10.856, p=0.028), lifestyle and self-management counselling (χ2= 9.143, p=0.002), knowledge (χ2= 8.129, p=0.004), and beliefs (χ2= 18.228, p=0.000). Female patients were more likely to be compliant with health behaviors than their male counterparts. Patients who were housewives were found to be more compliant than those who were working, non-employed, or retired. Participants with high scores on the lifestyle and self-management counseling, on the patients’ knowledge about hypertension, and on the patients’ beliefs about hypertension were found to be more compliant than those with low scores (Table 7).

| Table 7 Association between compliance and various factors |

According to binary logistic regression results, gender, lifestyle and self-management counseling, high knowledge, and beliefs scores were found to be independent predictors of compliance. Being female increased the odds of compliance with lifestyle recommendations about 2 times (OR 1.9 [1.2–3.1]). Patients who got high scores in lifestyle and self-management counseling, knowledge, and beliefs about hypertension were OR 1.5 [1.1–2.1], OR 2.9[1–8.4], and OR 2.7[1.4–4.9] times, more compliant than those who got low scores, respectively (Table 8).

| Table 8 Independent predictors for compliance |

Discussion

This study has shown that 23% of the patients were fully compliant with healthy lifestyle behaviors, about 95% were knowledgeable about hypertension, and 86% had positive beliefs about the management protocols of their disease. Gender, physician counseling on a healthy lifestyle, patients’ beliefs about hypertension management, and their knowledge on hypertension and its management have an independent effect on compliance with lifestyle recommendations.

Several studies have defined compliance as the willingness of the patients to change their lifestyle according to physician recommendations and take responsibility for their health.23–25 Factors that affect the compliance rate can be divided into external and internal factors. External factors include the impact of health education, the support from the family and friends, and the relationship between the patient and physician. Internal factors include sociodemographic characteristics, attitude, and emotions caused by the disease.24,25 In this study, only 23% of the patients were fully adherent to healthy lifestyle behaviors. This low rate could be due to the poor relationship between the patient and the physician and/or lack of support from family and friends.26,27 In another study, it was found that somewhat hypertensive patients did not follow healthy lifestyle behaviors.23

The effect of knowledge and beliefs about hypertension and its management is concordant with the known theoretical model relating attitudes to changes in lifestyle behaviors, as well as results of former studies reporting that patient education about hypertension and lifestyle changes and physician counseling improved blood pressure control.2,28–30 Based on the previous studies, patients who are more knowledgeable can play an active role in the management of hypertension and therefore are more effective in controlling their BP. In this study, the overall knowledge and beliefs scores were high (95% and 86%, respectively). This finding was similar to another study’s finding that showed that the scores of hypertensive patients’ knowledge and beliefs were also high.17 However, another study found the low rate of knowledge about hypertension.31 Despite the high score of patients’ knowledge and their positive beliefs, the compliance rate was low. The low compliance rate may be due to the weak relationship between patients and physicians and lack of support by the family and friends or maybe the patients not following the recommendations in the correct way.32

The role of gender in compliance with disease management among hypertensive patients is still unclear. The majority of the studies found that female gender was associated with better compliance.33 The nature of being female, her life, and her fears about the disease may play a role. This study reported that there was a significant association between patients’ compliance with lifestyle recommendations and gender. Female patients were more compliant than male patients (p=0.005). In Japan, similar findings were found.8 However, a study conducted in Turkey did not find gender to be an independent predictor of compliance with hypertension management.15

Lifestyle counseling by the physician about diet, weight loss, physical activity, and smoking can play an important role in promoting a healthy lifestyle.34 In this study, lifestyle and self-management counseling was found to be an independent predictor of patients’ compliance with lifestyle recommendations (p=0.008). Patients who got high scores (56%) in the counseling section of the survey were more adherent than those who got low scores (44%). This finding was similar to another study which found that 88% of the patients who were received counseling reported adherence to healthy lifestyle recommendations.35

Knowledge about hypertension disease is an integral part of the chronic care model which requires patients with chronic diseases to be knowledgeable and active partners in the management of their conditions.36 Also, patients’ beliefs about the effectiveness of hypertension treatment were related to different hypertension self-management behaviors.37,38 In this study, knowledge about hypertension was found to be an independent predictor patients’ compliance with lifestyle recommendations (p=0.043). Patients who got high scores in the knowledge section of the survey (95%) were more compliant than those who got low scores (5%). Also, patients’ positive beliefs about hypertension management were found to be another independent predictor (p=0.001). Patients who got high scores (86%) in the beliefs section were found to be more compliant with healthy lifestyle recommendations than those who got low scores (14%). These findings were similar to another study conducted in Israel which found that beliefs and knowledge about hypertension and its management were independent predictors of compliance with lifestyle recommendations.17

In this study, age was not found to have a significant association with hypertensive patients’ compliance with lifestyle recommendations. This finding contrasts with the finding of a previous study which was carried out in Saudi Arabia and found that patients who were <65 years old were more adherent to a healthy diet than older patients.14

There was no statistically significant association between compliance with lifestyle recommendations and the level of monthly income in this study (p>0.05). A contrary finding was reported in other studies8,14,15 where the level of monthly income affected the adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors. Education level was not found to have any association with hypertensive patients’ compliance with lifestyle recommendations in this study (p>0.05). This finding contrasts with the findings of similar studies which found that education level was associated with better adherence.14,39

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, all information in this study was obtained through a self-report method. The information may be inaccurate because of “social desirability” responses or recall difficulties. However, there is no alternative source of information regarding patients’ behaviors and physicians’ lifestyle counseling as this is not recorded in the medical files. Also, patients are considered a reliable source for this type of information. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the design prohibits conclusions about cause and effect, and therefore, we refer only to an association between compliance to lifestyle behaviors and the independent variables in the binary regression model. Third, this study was conducted in one hospital in the north of Jordan. The study participants may not be an accurate representative of all hypertensive patients in the community, and henceforth, the study findings are not generalizable to the general population. However, it should be noted that the hospital serves as a referral hospital and provides primary, secondary, and tertiary health-care services to more than one million inhabitants.

Conclusion

This study showed that despite the high level of patients’ knowledge about their hypertension disease and their positive beliefs about their disease management, the rate of compliance with recommended lifestyle behaviors was low. Compliance with lifestyle recommendations was significantly associated with female gender, being a housewife, lifestyle and self-management counseling, and patients’ knowledge and positive beliefs about hypertension.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Karen Rascati, PhD (University of Texas at Austin) for proofreading the manuscript. This study was supported by Jordan University of Science and Technology, Grant: 405-2016.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–520. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427

2. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JJL. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–2571. doi:10.1001/jama.289.19.2560

3. Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, Mann S, Lindholm LH, Kenerson JG. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community. J Clin Hypertens. 2014;16(1):14–26. doi:10.1111/jch.12237

4. Cryer MJ, Horani T, DiPette DJ. Diabetes and hypertension: a comparative review of current guidelines. J Clin Hypertens. 2016;18(2):95–100. doi:10.1111/jch.12638

5.

6.

7. Siervo M, Lara J, Chowdhury S, Ashor A, Oggioni C, Mathers JC. Effects of the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet on cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(01):1–15. doi:10.1017/S0007114514003341

8. Kim Y, Kong KA. Do hypertensive individuals who are aware of their disease follow lifestyle recommendations better than those who are not aware? PLoS One. 2015;10(8):1368–1378.

9. Mungal-Singh V. Lifestyle changes for hypertension. South Afr Family Pract. 2012;54(2):S12–S16. doi:10.1080/20786204.2012.10874203

10. Jaddou H, Batieha A, Khader YS, Kanaan A, El-Khateeb M, Ajlouni K. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control, and associated factors: results from a national survey, Jordan. Int J Hypertens. 2011;2011:8287–8297. doi:10.4061/2011/828797

11.

12. Serour M, Alqhenaei H, Al-Saqabi S, Mustafa A-R, Ben-Nakhi A. Cultural factors and patients’ adherence to lifestyle measures. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(537):291–295.

13. Gee ME, Bienek A, Campbell NR, Bancej CM, Robitaille C, Kaczorowski J. Prevalence of, and barriers to, preventive lifestyle behaviors in hypertension (from a national survey of Canadians with hypertension). Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(4):570–575. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.09.051

14. Elbur AI. Level of adherence to lifestyle changes and medications among male hypertensive patients in two hospitals in Taif; Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(4):168–172.

15. Uzun S, Kara B, Yokuşoğlu M, Arslan F, Yılmaz MB, Karaeren H. The assessment of adherence of hypertensive individuals to treatment and lifestyle change recommendations. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2009;9(2):102–109.

16. Alhalaiqa F, Deane K, Nawafleh A, Clark A, Gray R. Adherence therapy for medication non-compliant patients with hypertension: a randomised controlled trial. J Hum Hypertens. 2012;26(2):117–126. doi:10.1038/jhh.2010.133

17. Heymann AD, Gross R, Tabenkin H, Porter B, Porath A. Factors associated with hypertensive patients’ compliance with recommended lifestyle behaviors. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13(9):553.

18. Leon N, Charles S, Magloire D, Clemence M, Azandjeme C, Paraiso NM. Determinants of adherence to recommendations of the dietary approach to stop hypertension in adults with hypertension treated in a hospital in benin. Univers J Public Health. 2015;3(5):213–219. doi:10.13189/ujph.2015.030506

19. Xu K, Ragain R. Effects of weight status on the recommendations of and adherence to lifestyle modifications among hypertensive adults. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19(5):365–371. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1001828

20. Neutel CI, Campbell NR. Changes in lifestyle after hypertension diagnosis in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24(3):199–204.

21.

22.

23. Alhalaiqa F, Al-Nawafleh A, Batiha AM, Masa'deh R, Abd Al-Razek A. A Descriptive Study of Adherence to Lifestyle Modification Factors among Hypertensive Patients. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47(1):273–281. doi:10.3906/sag-1508-18

24. Kyngäs H, Lahdenperä T. Compliance of patients with hypertension and associated factors. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29(4):832–839.

25. Peck DF. Compliance with therapeutic regimens. J Med Ethics. 1977;3(3):148. doi:10.1136/jme.3.3.148

26. Seeman TE. Health promoting effects of friends and family on health outcomes in older adults. Am J Health Promotion. 2000;14(6):362–370. doi:10.4278/0890-1171-14.6.362

27. Gallant MP. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: a review and directions for research. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(2):170–195. doi:10.1177/1090198102251030

28. Abid A, Galuska D, Khan L, Gillespie C, Ford E, Serdula M. Are healthcare professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? A trend analysis. Med Gen Med. 2004;7(4):10.

29. Roumie CL, Elasy TA, Greevy R, Griffin MR, Liu X, Stone WJ. Improving blood pressure control through provider education, provider alerts, and patient education: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(3):165–175.

30. Hroscikoski MC, Solberg LI, Sperl-Hillen JM, Harper PG, McGrail MP, Crabtree BF. Challenges of change: a qualitative study of chronic care model implementation. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(4):317–326. doi:10.1370/afm.570

31. Iyalomhe GB, Iyalomhe SI. Hypertension-related knowledge, attitudes and life-style practices among hypertensive patients in a sub-urban Nigerian community. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2010;2(4):71–77.

32. Schaefer C, Coyne JC, Lazarus RS. The health-related functions of social support. J Behav Med. 1981;4(4):381–406.

33. Jin J, Sklar GE, Oh VMS, Li SC. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient’s perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(1):269. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S1458

34. Milder IE, Blokstra A, de Groot J, van Dulmen S, Bemelmans WJ. Lifestyle counseling in hypertension-related visits–analysis of video-taped general practice visits. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9(1):1. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-9-58

35. Lopez L, Cook EF, Horng MS, Hicks LS. Lifestyle modification counseling for hypertensive patients: results from the national health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2004. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22(3):325–331. doi:10.1038/ajh.2008.348

36. Schapira MM, Fletcher KE, Hayes A, Eastwood D, Patterson L, Ertl K. The development and validation of the hypertension evaluation of lifestyle and management knowledge scale. J Clin Hypertens. 2012;14(7):461–466. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7176.2012.00619.x"

37. Bokhour BG, Cohn ES, Cortés DE, Solomon JL, Fix GM, Elwy AR. The role of patients’ explanatory models and daily-lived experience in hypertension self-management. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(12):1626–1634. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2141-2

38. Ross S, Walker A, MacLeod M. Patient compliance in hypertension: role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18(9):607–613. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1001721

39. Mahmoud MIH. Compliance with treatment of patients with hypertension in Almadinah Almunawwarah: A community-based study. J T U Med Sc. 2012;7(2):92–98. doi:10.1016/j.jtumed.2012.11.004

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.