Back to Journals » Journal of Healthcare Leadership » Volume 7

Facilitating the implementation of evidence-based practice through contextual support and nursing leadership

Authors Kueny A, Shever L, Lehan Mackin M, Titler M

Received 1 December 2014

Accepted for publication 9 February 2015

Published 24 June 2015 Volume 2015:7 Pages 29—39

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S45077

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Russell Taichman

Angela Kueny,1 Leah L Shever,2 Melissa Lehan Mackin,3 Marita G Titler4

1Luther College, Decorah, IA, 2The University of Michigan Hospital and Health Center, Ann Arbor, MI, 3University of Iowa College of Nursing, Iowa City, IA, 4University of Michigan School of Nursing, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Background/purpose: Nurse managers (NMs) play an important role promoting evidence-based practice (EBP) on clinical units within hospitals. However, there is a dearth of research focused on NM perspectives about institutional contextual factors to support the goal of EBP on the clinical unit. The purpose of this article is to identify contextual factors described by NMs to drive change and facilitate EBP at the unit level, comparing and contrasting these perspectives across nursing units.

Methods: This study employed a qualitative descriptive design using interviews with nine NMs who were participating in a large effectiveness study. To stratify the sample, NMs were selected from nursing units designated as high or low performing based on implementation of EBP interventions, scores on the Meyer and Goes research use scale, and fall rates. Descriptive content analysis was used to identify themes that reflect the complex nature of infrastructure described by NMs and contextual influences that supported or hindered their promotion of EBP on the clinical unit.

Results: NMs perceived workplace culture, structure, and resources as facilitators or barriers to empowering nurses under their supervision to use EBP and drive change. A workplace culture that provides clear communication of EBP goals or regulatory changes, direct contact with CEOs, and clear expectations supported NMs in their promotion of EBP on their units. High-performing unit NMs described a structure that included nursing-specific committees, allowing nurses to drive change and EBP from within the unit. NMs from high-performing units were more likely to articulate internal resources, such as quality-monitoring departments, as critical to the implementation of EBP on their units. This study contributes to a deeper understanding of institutional contextual factors that can be used to support NMs in their efforts to drive EBP changes at the unit level.

Keywords: evidence-based practice, institutional context, driving forces, nurse managers

Introduction

A crucial factor in delivering high-quality patient care is nursing implementation of evidence-based practice (EBP); institutional leadership, such as nurse managers (NMs), plays an integral role in the implementation of EBP on nursing units.1 EBP allows nurses to make complex health care decisions based on findings from rigorous or high-quality research reports, clinical expertise, and patient perspectives.2,3 NMs have dynamic roles to help facilitate EBP at the unit level, and a more thorough description of their role related to EBP at the unit level is discussed by Shever et al (unpublished data, 2014). Original models of implementing EBP within the health care setting suggest that there is a systematic process that moves in cyclical patterns to support providers making these complex decisions. This process begins with an impetus for change, such as a recent research report, patient outcomes, or clinical audit. Subsequent steps include conducting a literature review and evaluation of the identified topic, implementing and evaluating trial changes within practice, and proposing recommendations for clinical practice guidelines.4,5 The process allows nurses to be an integral part of the health care team and can drive EBP change and contribute to the provision of high-quality care. NMs need institutional contextual support for themselves and their staff on the hospital unit to create an environment that drives change with EBP.

Models for EBP implementation provide stepwise guidance; however, particular contextual factors act as facilitators or barriers to the process. A concept analysis by McCormack et al6 defined context as a dynamic component impacting the implementation of EBP, working in conjunction with workplace culture and leadership. NMs are one of the hallmark components of the health care context impacting whether or not EBP is successfully adopted.1 Shever et al identified tactics and roles of the NM in the implementation of EBP (unpublished data, 2014). It is important to understand how an institutional context supports NMs in their roles to facilitate implementation of EBP on their supervising units. To address this gap, the purpose of this article is to identify contextual factors described by NMs, to compare and contrast these perspectives across nursing units, and to relate this to driving change within the institution. The aims of this qualitative study were to a) describe NMs’ perspectives of contextual factors related to implementation of EBP, b) identify driving forces recognized by NMs to facilitate EBP, and c) compare contextual factors and driving forces across high- and low-performing nursing units.

Background

Change in practice relies not only on the nature and strength of the evidence but also on the practice environment in which practice is to be placed and the method by which the process is facilitated.1,7 Ellis et al recognized that original models of EBP did not necessarily emphasize the influence of existing workplace environment or cultural factors.8

… it is recognised that getting the best evidence into practice relies on more than just the provision of best information. The translation from workshop to work practice is also influenced by a range of other factors such as work culture and environment, management structures, and resources.8

McCormack et al elaborate on the workplace environment and culture by delineating characteristics of context, including nuanced differences between context, culture, and leadership.6 Similarly, prior research highlights organizational factors supportive of implementing EBP and suggests a necessity for the combination of all three components, including the following: a) leadership of supportive and committed managers; b) a workplace culture that empowers nurses and reinforces EBP; and c) measurement of ways in which patient outcomes are improved through EBP.2,9–11 The integration of these factors facilitated within the institutional approach to EBP allows nurses to feel empowered to create change in practice that is supported by contemporary and relevant evidence. A supportive institutional culture, an impetus to drive change, and an established process by which change is initiated and managed (preferably, by health care team members) can be further complemented by contextual factors that include easily accessible information, ample resources to make change, and the presence of personnel skilled to drive change in practice.8 Prerequisite skill and strong leadership become a catalyst for the culture and contextual resources required to implement EBP. Nurses identify administrative support as necessary for research utilization and simultaneously recognize a lack of administrative support as a barrier to EBP implementation.11 Therefore, NMs play an integral role in advocating the creation of a culture supportive of EBP and may be required to transfer administrative support to staff nurses in order to make change happen.

In addition to contextual influences internal to the institution, external factors and bodies impact the implementation of EBP. As examples, Transforming Care at the Bedside (TCAB) and Magnet models recommend change initiatives involving nurses at every level of the organization.12,13 TCAB is an initiative from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement that supports health care settings to improve care, improve staff satisfaction, and implement change.12 The Magnet Recognition Program through the American Nurses Credentialing Center recognizes health care organizations focused on quality patient care and nursing excellence using a thorough review of facilities desiring designation.13 These models focus on the shared responsibilities of EBP implementation at every level of nursing practice including bedside nurses, highlighting the need for managers and nursing leaders to become facilitators in the empowerment process. Furthermore, TCAB and Magnet models encourage decentralized institutional governance structures that would allow more individuals to become change catalysts. Facilitating nurses to move into these positions will shift institutions toward development and evaluation of EBP-based guidelines that may likely result in higher quality patient care.

The 2011 strategic plan of the National Institute of Nursing Research recognizes the need to bring evidence to patients. The report calls forth, “As we move forward in this rapidly evolving landscape, the expertise, innovation, and leadership skills of nursing scientists and clinicians will be increasingly called upon to guide and shape practices and policies” (p 3).14 Given the need for an existing infrastructure to allow for EBP as a reality in nursing and hospital environments, we describe NMs’ perceptions of the support available for their role and needs in promoting EBP with their nursing staff on nursing units.

Methods

A descriptive qualitative design was utilized to collect and analyze data from NMs from high-performing units (HPUs) and low-performing units (LPUs).15 It provided a rich picture of the type of contextual factors that support NMs as they implement EBP on their hospital units. Following data collection, inductive descriptive content analysis was used to analyze the data. This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Iowa institutional review board.

Sampling and procedures

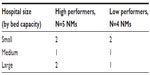

The sample of NMs was identified from 148 nursing units from 48 hospitals that participated in a larger nursing effectiveness study.16 Results of that study have been published elsewhere. Nursing units included in the original study provided care to a variety of patients that included medical, surgical, medical/surgical mixed, specialty (eg, orthopedics, oncology, cardiology/telemetry), pediatric, mother–baby, rehabilitation, and psychiatric. The primary investigator intended to compare NMs regarding promotion of EBPs across different types of units with varying sizes, patient outcomes, and EBP implementation. The original nursing units were stratified by size of the hospital in which they were housed: 1) small (≤100 licensed beds), 2) medium (101–400 licensed beds), and 3) large (>400 beds). Further stratification was done by identifying both HPUs and LPUs in EBP implementation based on factors identified in the larger study regarding the number of evidence-based interventions performed, scores on the Meyer and Goes research use scale,17 unit fall rate, and fall injury rate. The Meyer and Goes scale measured assimilation of innovations onto hospital units focusing on contextual attributes, innovation attributes, and the interaction between these.17 Unit fall injury rate was used because it was one of the two outcome variables of interest of the original study (falls and falls with injuries). The better the fall rates, the better the units were doing toward preventing falls. Project managers, interviewers, and data analysts were all kept blind to performance designations until comparison of findings across units was required. NMs were randomly selected from each level of stratification and invited via e-mail to participate in telephone interviews. Table 1 presents NM stratification. The study includes nine NM participants representing all six subgroups. Three groups had only one participant because saturation was reached before additional participants were interviewed.

| Table 1 NM-stratified categories |

All of the NMs who participated in this study were female. The average experience as an NM was 6.5 years (range from 9 months to 33 years). The degrees held by NM participants varied, including diploma (1), associate’s degree (2), bachelor’s degree (1), and master’s degree in nursing (5). Almost all of the NMs had at least one certification, including Medical-Surgical Nursing Certification, Oncology Nursing Certification, and Critical Care Registered Nurse Certification.

Interviews

The structured interview guide was developed for this study by the study investigators. Questions were developed based on a review of the literature as well as feedback from experts in EBP implementation. There were approximately 30 questions divided into five parts: personal understanding of EBP (eg, definition, examples), institutional infrastructure for EBP (eg, triggers for change, resources to facilitate change, education, training), personal strategies to promote implementation of evidence on the unit (eg, examples, ways to recognize staff, assets, barrier), administrative practices (eg, use of evidence for administrative decisions, accountability for using EBP), and demographics (eg, education, number of years as manager). Example questions include the following: a) Please describe any group, council, or committee within your hospital that is helpful in fostering the use of EBPs on your unit; b) What are your immediate supervisor’s expectations regarding EBP? Verbal consent was attained at the time of acceptance to interview, and NMs mailed written informed consent forms to the research team. Three trained research assistants conducted interviews over the phone at a time that was convenient for both the subject and the interviewer. Interview duration was between 40 minutes and 60 minutes. The interviewer was blinded to the unit’s status as either an HPU or LPU. The interviews were audio recorded and then later transcribed for analysis. Saturation was determined when we received multiple overlapping responses across participants, and we had NMs from each of the performance/hospital size categories in Table 1.

Analysis

Two researchers read each interview transcript using descriptive inductive content analysis to identify overarching patterns across participants. Identified patterns along with the specific aims of the research study created a set of descriptive constructs and codes and provided a framework to build a more in-depth analysis of themes and concepts across participants. The initial basic framework, or the basic descriptive constructs, included “role of NM”, “clinical content areas”, “administrative practices supported by EBP”, and “infrastructure/driving forces”. By consensus, the researchers defined each construct to facilitate consistent identification of themes across all interviews. Each interview transcript was analyzed by two researchers with a third “checker” to ensure consistency across coding as definitions for constructs, themes, and subthemes became more refined.15 Any discrepancies in theme identification were discussed and in all cases were resolved by consensus. At this phase of the analysis, performance designations were unblinded so that HPUs and LPUs could be identified and comparisons made across units. A software program was not used to aid analysis, but content-analytic summary tables were used to categorize codes and themes by HPUs and LPUs.18 HPUs and LPUs within each theme were then compared using both codes and quotes from interviews. For the purpose of this paper, the theme and constructs related to infrastructure and driving forces are the focus. The “role of the NM” is reported in other findings, and will be reserved for that forthcoming manuscript.

Results

Within the overarching theme of institutional infrastructure, three major subthemes evolved from the analysis that highlighted contextual factors perceived by NMs to influence implementation of EBP in the clinical environment. Some examples describe support provided directly to the NM in her role, while other examples describe support for staff nurses under the NM supervision; both of these support NM’s expectation and oversight of the use of EBP at the unit level. These examples are woven together because NMs recognized both these types of support as helpful to their goal to provide EBP at the unit level. Culture, structure, and resources were perceived by NMs to empower nurses and initiate change on their nursing units to improve patient care. Additionally, NMs of HPUs and LPUs recognized varying driving forces to implementation of EBP.

Culture

Although workplace culture is sometimes subsumed under context, or even structure, it is discussed as unique here because NMs identified specific factors attributed to culture that impacted EBP change on their unit. Culture is defined here as the values and beliefs that drive behaviors and decisions within an institution. Different aspects of institutional culture served as both facilitators and barriers of EBP.

Hospital culture

Overwhelmingly, NMs of both HPUs and LPUs described a hospital-level culture supportive of EBP. Four NMs from HPUs described an overarching hospital culture that held specific nursing units accountable to initiate EBP change and implement EBP practices, while NMs representing two LPUs also described a supportive hospital culture. Specific to support for NMs in their role, a common thread among NMs from HPUs was cultural support of NM-comprised management teams that provided mentorship and immediate feedback, and served as a collaborative body that empowered NMs to make effective changes on their units. One HPU manager says,

[…] we [NM Management Team] actually all sit down every quarter and have educational opportunities for [unit] leaders. Sometimes it’s management or evidence-based techniques or practices, sometimes it’s clinical processes. We all sit down together as a group and go over […] and determine a plan of action on how we’re going to institute those kinds of things. Before we give education to the staff, we’re usually sitting down together as a group because […] we have to figure out how we’re going to be able to incorporate being able to maintain [and] hardwire the processes.

This highlights that supportive culture not only values a high level of responsibility for NMs to implement EBP, but also they are provided a collaborative atmosphere in which to create strategies and operationalize the processes required to make change.

One HPU NM described her institutional administration as a barrier to making changes in policies despite the parallel expectation of EBP adoption and implementation. She described how she wanted to make changes across departments, but lacked support from administrative superiors to make these changes. This NM described situations where units had evidence to support improved practice; however, administrative support for sharing findings with other units was absent. Although the high performance of this nursing unit suggests that the NM was motivated to promote EBP change, she was frustrated by the inconsistency between administrative expectations and administrative support.

Although many of the NMs from LPUs described a supportive atmosphere, they were vague about strategies employed to assist NMs to motivate nurses at the unit level to take accountability for EBP. As an example, one LPU NM articulated the general support of hospital administration for EBP as a concept, “I think the vocabulary itself of evidence-based is the whole aura throughout the hospital.” LPU NMs described a lack of administrative guidance in methods or approaches by which to assist staff to implement EBP. One NM described the administrative approach of taking national initiatives to the unit nurses to have them decide how to implement necessary changes without providing a vision of how to support this change. While it may be beneficial for unit nurses to be involved in the change adoption process, many are likely to lack the necessary knowledge and skills required by the EBP implementation process to lead efforts at practice change. This approach may be indicative of the low performance in EBP earned by this nursing unit.

When Joint Commission or another regulating body demands a change in practice, the hospital is expected to make the required changes in order to be accredited and demonstrate a commitment to patient safety and quality issues. NMs in all groups recognized the impact that external regulatory forces had on administrative expectations for EBP. One NM reflects, “… overall, it comes from a national patient safety goal or a joint commission’s goal. So you know, it’s not something you say … we all need to do it.” Despite this shared understanding, the communication of necessary changes from administrative to staff nurse levels differed between HPUs and LPUs. HPU NMs tended to describe environments where communication about necessary change was openly discussed and advertised. For example, one HPU NM said that her CEO hosts “Town Hall Meetings” to directly inform the managers of change, in addition to flyers placed on nursing units to announce changes in practice. Additionally, HPU NMs had opportunities to attend conferences or in-services that provided education about practice changes required by regulatory bodies, which gave these NMs foundational information on how to communicate with the hospital administration about strategies and foreseen barriers of implementing the change on their respective units. LPU NMs provided examples of hospitals sending nurses to external programs such as TCAB conferences, the Chapman Scholar Program (identified by the NMs as an opportunity funded by their hospital to conduct research), or Magnet meetings, which furthered NMs knowledge and skills in supporting unit-level EBP change. The hospital culture is an important component that helps to bring some of the expectations of regulatory bodies and health care trends to nursing units. A hospital culture that transmits new messages from regulatory bodies using organized meetings and pertinent information helped NMs to feel supported in implementation of EBP on their nursing units with a greater understanding.

A supportive hospital culture supports interdisciplinary buy-in from across disciplines and up and down the power hierarchy within the organization to make change happen. An HPU NM describes this collaboration as,

So, from our board of trustees downward we get the buy-in and then, sometimes when we’re trying to change nursing process–sometimes it comes from the quality side, sometimes it comes from the nursing side. But we collaborate with everybody involved in the room, because there are representatives from all the clinical areas […]

The NM identified that the advantage of this process is that nurses’ voices are heard across the organization, and it results in faster implementation of changes in practice. Considering the relationship of multidisciplinary team members, is critical to understanding change, and those who will be invested in the change at the unit level.

Culture of expectations

The NM heavily influences the shaping of a unit environment, and these NMs described leadership strategies to empower their staff nurses to implement EBP. An NM from an HPU describes her staff,

I set really high expectations for my staff and they have really risen to the occasion. I’m just now starting to really reap the benefits of having very active committees, my staff experts […] they drive their own work environment […] I can’t be in the committees–if they want me to go and answer some questions I will. But I pretty much have said, I trust you […] . I know what your capabilities are, you don’t need a unit coordinator to be sitting in these committees because you all are the experts.

Nursing managers ensure opportunities for staff nurses to be active participants in implementing EBP on the unit.

I send people to programs and send them to evidence-based in-services, and we try to cover them so they can go while they’re at work. We take decisions back to the area coordinating team and let them do the work […]. I see my staff being more as a unit presentation, not me presenting everything […] I want them to be accountable for their unit and for the best patient care on this unit. I don’t know if everybody sees it that way, but I can see it and I hope eventually they see all of it.

These NMs are actively building units in which the staff nurses are involved with committees, hospital-wide initiatives, unit decisions, and education. One NM from an HPU had extra assistance with this process by creating a position, in addition to another manager or a charge nurse, that she called a “unit coordinator”. She reported her role as,

[…] we reinforce that the unit coordinators, […] they’re not charge nurses, they’re considered management. They’re reinforcing […] new information and new technology, new skills […] every shift they’re here having a rounding with my staff.

She recognized that she cannot be present for every shift and the importance of having someone designated as oversight for EBP implementation. These NMs who were motivated and set high expectations for their staff transferred their motivation to the nursing staff to drive change and current practice.

NMs expressed understanding their role as communicators of administrative expectations for necessary change and consistent implementation of EBP. NMs on HPUs described an atmosphere where administrative expectations of EBP were met with rewards and consequences and provided impetus for EBP implementation to be prioritized on these units. As one HPU NM discussed, she described a merit scale that was proportionate to their participation in driving change on their units and ultimately impacted their salaries. This tangible stimulus encouraged NMs to hold unit-level nurses responsible for carrying out EBP strategies that were administrative expectations.

Structure

The structure of an institution guides the processes of care. This includes the hierarchy of leadership, and the hierarchy of decision making within the institution. NMs reflected on these aspects of structure impacting their ability to implement EBP.

Engaging nurses in decision making through shared governance

Nursing managers from all units saw shared governance models as avenues for nurses’ involvement in hospital-wide EBP initiatives. More LPU NMs described working with shared governance models than HPU NMs. The shared governance model ensures activity from all levels of employees to participate, and gives the structure that some organizations need to work together toward EBP goals. One LPU NM defines it clearly by stating,

We have six shared governance committees–a nursing practice committee, a nursing research committee, a nursing education committee– the shared leadership committee members bring forth the issues of the unit, based on the quality committee. Then [they] bring it to the most appropriate shared governance […] you have representation from all of the divisions, there’s the medicine representative, the surgical representative, so it’s brought up to a higher level […] they in turn look at it on an organizations stand-point; practice, education, research, everything, and make decisions […] they focus and filter it up and down in order to change policies, protocols, and things like that.

On one LPU, the nursing assistants recognized the need for more equipment at the bedside, and had a place to bring those concerns to the shared governance committees to be heard hospital-wide. Their NM recognized, “And I think having more people involved on your shared governance committees and letting them bring back the updates is needed.” Shared governance is certainly an avenue for all staff to contribute ideas or strategies within the larger hospital structure, relieving some pressure from the NM to provide avenues toward change on her own.

NMs described nurses’ involvement in shared governance committees as positive, but their level of power for decision making was sometimes unclear. The committees would make the policies and procedures, and nurses helped to disseminate mass e-mails to communicate the changes coming to the hospital. Nurses brought policy change suggestions to the meetings, attended the meetings, and brought information back to the nursing units. To describe the process of nursing involvement in a policy/procedure committee, one NM explains,

[…] she [nurse] did research […] and found a study that was published […] so we’re changing our neutropenic diet and allowing flowers and kind of changed that because of the research that she found […] if it involves anything that is a policy or procedure, then it has to go in front of the practice council and then they basically review them at the council and any changes that were made […] get sent out.

Although nurses are actively involved in information presented at these councils, the final decision making for policy change does not necessarily rest in the hands of nursing alone, as described here, because the shared governance committee makes that final decision. This has the potential to remove some of the autonomy in decision making for EBP recommendations.

Despite some of the uncertainty of nurses’ final decision-making capabilities within the institution, HPU NMs articulated avenues that nurses were making decisions within the institutions on nursing-specific committees within units. Unit-based committees were an important aspect of institutional structure that allowed nurses to be involved in decisions to implement EBPs, supporting NM expectations to drive change.

Engaging nurses in decision making through committees

While more LPUs use shared governance models and multidisciplinary committees than HPUs, nurse-specific committees are mentioned more frequently by HPU than LPU NMs. NMs recognized the power of nurses in decision making reflective of their scope of practice. HPUs had a variety of specific practice-oriented committees, such as wound care, infection protection, and diabetic education. NMs of LPUs mentioned one specialty committee for pressure ulcers, and involvement in TCAB through committee work. The overlaps across HPUs and LPUs are the research/EBP committees, nursing practice, unit-based councils, nursing practice committees, and nursing education committees. None of the LPU NMs mentioned nurses’ involvement in quality improvement committees.

HPU NMs expressed nursing committee membership as a way to create change in nursing practice, and describe their nurses feeling empowered to create and implement these changes through their committee membership. One NM from an HPU told us,

We also have a nurse practice council that actually looks at policies and through evidence-based practice what is best and how to change these policies […] if you do it right and do a quality rounding instead of just to stand in the room to make sure that they’re okay […] and this is now policy […] we’ve tweaked the policy a couple times as to making sure that it identifies what we want- that the actual outcome is what we want.

The structural arrangement of hospitals that focused on nurses’ involvement in committees pulled forward nurses from all levels to be part of change recommendations and implementations for patient care. NMs need hospitals that encourage structures for nursing-specific committees and allow nurses to make EBP recommendations for practice.

Resources

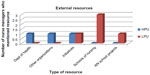

Accessibility and types of resources motivate and influence how hospitals and NMs can work with staff to change policy in support of the best practice. Despite positive aspirations and supportive hospital cultures of EBP, NMs articulated the continual need for resources to support these aspirations to make change and implement EBP at the unit level. HPUs and LPUs have resources that NMs reflect as internal and external. Figure 1 displays the internal resources, while Figure 2 displays the external resources described by these NMs. From these figures, it is clear that HPUs were able to describe a greater quantity of internal resources than the LPUs. LPU NMs concentrated on library resources, advanced practice nurses within their organization, and Internet or computer information to support their expectations of staff use of EBP. Internet and computer information included the Intranet services that allow employees to spread information from committee work, and minutes from meetings. Only HPUs had access to a quality department, and NMs from LPUs described a research board to help them make their decisions for any practice changes.

With recent budget constraints, NMs acknowledged the need for institutional financial resources to accomplish necessary education and projects they desired based on EBP. NMs considered conferences an important piece of implementing EBP, and they attended conferences themselves and sent staff nurses from their units to conferences for educational advancement. One NM mentioned that, with the downturn in the economy recently, she received less funding for attending conferences. One of the HPU’s hospital administrations paid for the staff involvement in committee work or non-patient care days to conduct research or education on a topic of staff choice. One of the HPU NMs received funds for high performers on her unit to use as an incentive to promote EBP, stating,

we have a zero to five percent [increase] merit […] I mean one they get highlighted, you know, they get a lot of personal praise and recognition, like we have a newsletter that goes out to our staff, so of course they get recognized in that […] in order to get a five percent [increase salary] you have to be an active participant in driving change.

LPU NMs mentioned conferences as their main reason for seeking funding from their organization’s administration.

Paid internships by the institution provided another source of education and research for staff nurses. Two LPU NMs described internships that assisted staff nurses in developing leadership skills and in conducting research to present new information to their units. These were both internally and externally funded internships.

One of the [internship staff] did one [project] on neutropenic diet for our cancer unit and one of the things […] they don’t get flowers, they don’t get peppers, raw vegetables, that kind of thing […] she was looking for a project for the leadership and so she did research on that and found a study, so we’re changing our neutropenic diet and allowing flowers and kind of changed that because of the research she found.

These resources are helping nurses to keep current with research to maintain EBP on their units, building a culture of EBP the NMs desired.

Nursing managers provided insights and suggestions of ways to help them to motivate and involve their staff in implementing EBP. NMs called for the need for more advanced practice nurses available to every unit to help educate and implement EBPs with their staff nurses. Multiple NMs mentioned education funding for themselves and their staff for attending conferences and education sessions.

Driving change to implement EBP

Forces that influence change and implementation of EBP on nursing units were divided into two categories, internal and external. Internal forces that drive change were considered those inside of the hospital/institution and the nursing unit. Both HPU and LPU NMs emphasized that staff nursing recommendations helped to drive change. One HPU NM stated, “Basically a lot of these changes are nurse-driven. They come to me with ideas and I basically research the idea and come up with a decision. And that’s how I go about initiating whatever needs to be initiated.” Internal change also comes from the committees described in the “Structure” section. With administrative support, NMs were able to create new committees and keep their staff nurses active in committees. As an example, one HPU NM described, “I’m just now starting to really reap the benefits of having very active committees; they’re starting to see how they drive their own work environment.” Because of internal communication styles, such as Town Hall Meetings, there was a difference in how NMs felt that administrative expectations were passed down. This impacted the way NMs felt they were part of the process of driving change within the institution. HPU NM units tended to see change as positive and noted a more comprehensive effort to put the change into effect. LPU NMs, on the other hand, noted that change was sometimes perceived as more of a “top down” mandate. One LPU NM expressed, “It gets filtered down from the executive level to the managers and the managers filter it down to staff – but it’s always the what and why. The why is the most important because that – that’s what drives more understanding by us.” One of the most significant drivers of change for one HPU NM was the patient. She stated, “The bottom line is best patient outcome.” Internal forces that drive change included institutional avenues to receive direct staff nurse input and empowerment to review and implement EBP, clear and open communication with administrative levels, and the recognition of working toward change for the benefit of the patient.

External forces originating from outside the institution acted to produce change within institutions. The process of obtaining Magnet status and its relationship to producing evidence-based change were most frequently mentioned by LPUs. One LPU NM reflected, “We just finished re-designation for Magnet yesterday […] and to hear every one of the staff in all of those meetings talk about evidence-based [practice] […] it’s not just a term anymore […] people really understand it.” Conversely, HPU NMs identified external forces related to national safety initiatives or reaction to payment for services. One HPU NM described,

Money is certainly a factor and monetary principles. So when you talk about things like, that CMS [US Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services] is no longer going to pay for, you know, catheter associated infections, then you have a monetary, um, force that’s driving you to change practice to eliminate those – to change your benchmarks. Um, you know, so I would say that that’s part of what drives change.

Reflected within the culture of expectations earlier in this paper, the way that these external forces are passed to NMs to pass to nursing staff differed between HPU and LPU NM descriptions. All NMs recognized that there were external bodies that played a role in emphasizing EBP, providing resources to implement EBP, and driving change. However, NMs from LPUs identified the primary drivers of change as external forces such as Magnet status, without as much articulated support from internal forces as HPU NMs.

This research revealed that institutional contextual factors weighed heavily on NMs as they were supporting staff in the implementation of EBP on their units. Components of the context described by NMs include culture, structure, and resources available to support the implementation of EBP. Supportive cultural aspects included setting expectations and evaluations for NM and staff focused on EBP, institutional appreciation for involving staff in decisions, and collaboration or teamwork among the managers of different units. When these cultural supports were not in place, especially from upper administration, NMs turned to outside agencies for reasons why they had to make changes. On a practical level, supportive structures included shared governance models, or flat hierarchical institution models, and specialty/nursing/unit-specific committees. It was also apparent that internal resources supported HPUs, while LPUs’ had lower access to internal resources or quality departments within the institution. Creative strategies by NMs for educating and empowering staff to implement EBP are needed. The NMs were incredibly insightful of the resources available and the resources needed to implement EBP.

Discussion and conclusion

Ample research supports the importance of reviewing an institution’s context to understand how to best support the implementation of EBP at all levels of nursing.1,7,8,10,11 Qualitative research provides an opportunity to explain and reflect on in-depth explanations from the perspective of NMs as they are working to implement EBP themselves and serving in a role encouraging and empowering staff nurses to implement EBP at the unit level.19 McCormack et al give us a summary of indicators related to structure, culture, context, leadership, and evaluation that are related to strong and weak enablers of effective practice.6 NMs described here that culture, structure, and resources within the institutional context either empowered them to independently drive change or created barriers to them resulting in feeling disempowered to make change on their units. HPU NMs were talking about nurses driving change within the institution, demonstrating a sense of empowerment and accountability for that change. The NMs from those units had an independent voice with regard to their expectations and desires for action and committee work. Meanwhile, LPU NMs spoke more about external forces, administration, and outside influences for making changes or gathering teams. The independence of HPU NMs resulted from both the culture and structure of the larger institution. Their independence also reflects support from management team meetings and mentorship more so than LPU NMs. In addition, they also described more resources, both financially and strategically to support their role in empowering staff to use EBP at the unit level. These trends demonstrate the need for institutions to build a context that empowers NMs. Cummings et al state, “By providing opportunities for staff development and nurse-to-nurse collaboration and sufficient nurse staffing and support services, administrations make investments that result ultimately in better quality care for patients” (p S32).20 NMs can provide a catalyst to bring administrative support to unit and staff nurse level. They can create much from little but need to feel empowerment and accountability to make those changes happen.

Stetler emphasized the need to have an organized structure supportive of implementing EBP, allowing a culture of support for EBP to be enacted.10 Educational support was both desired and accessible at different levels across NM institutions. Previous research supports educational support for implementing EBP. One suggestion is education outreach visits.21 Another suggestion is to use the interns from Clinical Scholars Program,22 who receive mentorship and are motivated to implement EBP. These research findings support these recommendations with examples and excitement about education opportunities for staff nurses. Staff nurses can then bring those models back to their unit and committees, keeping with the trends of current evidence.

The Crossing the Quality Chasm Report23 defines goals for 21st century for implementing research into practice through EBP. This report focuses on the complex relationship between quality measurement within institutions and the health care delivery structure. Stronger quality departments within hospitals would help to achieve Institute of Medicine goals. Only HPU NMs in this study mentioned quality departments being readily available as a resource for nurses within the institution, although LPU NMs did mention area coordinators or patient care and delivery teams. Resources in place can bridge quality and risk assessments or policy reviews with other responsibilities to support NMs to implement EBP on their units.

In a qualitative study about middle managers, Dopson and Fitzgerald24 found important components to implement EBP, including collaborative relationships, EBP changes focused on targeted outcomes, the need to train managers to facilitate change, encouragement of open debate about best practice and evidence, and offering meaningful levers for change (ie, monetary or study leave). The findings from this study are reflective of some of these recommendations.

The limitations of this study are inherent within the qualitative method. Although we could report summative results of committees and resources available within these institutions, the number of participants (with only nine NMs) limits the generalizability to other NM experiences. While this study contributes to a deeper understanding of some of these contextual institutional factors affecting NMs ability to implement EBP on units with their staff, continual efforts to refine the measurement of context and its impact on practice are needed.25 Furthermore, it calls for future research developing a system to measure contextual factors related to HPUs and LPUs to identify large-scale differences and motivate institutions to make changes where necessary to create HPUs.

NMs perceived workplace culture, structure, and resources as facilitators or barriers to empowering nurses under their supervision to use EBP and drive change. A workplace culture that provides clear communication of EBP goals or regulatory changes, direct contact with CEOs, and clear expectations supported NMs in their promotion of EBP on their units. HPU NMs described a structure that included nursing-specific committees, allowing nurses to drive change and EBP from within the unit. NMs from HPUs were more likely to articulate internal resources, such as quality-monitoring departments, as critical to the implementation of EBP on their units. Workplace culture, structure, unit-level resources, availability of institutional resources, and institutional prioritization and expectation of EBP implementation supported NMs in their implementation of EBP in the clinical environment.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Gifford W, Davies B, Edwards N, Griffin P, Lybanon V. Managerial leadership for nurses’ use of research evidence: an integrative review of the literature. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2007;4(3):126–145. | |

Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Titchen A, Harvey G, Kitson A, McCormack B. What counts as evidence in evidence based practice? J Adv Nurs. 2004; 47(1):81–90. | |

Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB. Evidence Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. 2nd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. | |

Stetler CB. Updating the Stetler model of research utilization to facilitate evidence-based practice. Nurs Outlook. 2001;49(6):276. | |

Titler MG, Kleiber C, Steelman VJ, et al. The Iowa model of evidence-based practice to promote quality care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2001;13(4):500. | |

McCormack B, Kitson A, Harvey G, Rycroft-Malone J, Titchen A, Seers K. Getting evidence into practice: the meaning of ‘context’. J Adv Nurs. 2002;38(1):94–104. | |

Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, Seers K, Kitson A, McCormack B, Titchen A. An exploration of the factors that influence the implementation of evidence into practice. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:913–924. | |

Ellis I, Howard P, Larson A, Robertson J. From workshop to work practice: an exploration of context and facilitation in the development of evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2005;2(2):84–93. | |

Dobbins M, Ciliska D, Cockerill R, Barnsley J, DiCenso A. A framework for the dissemination and utilization of research for health-care policy and practice. Online J Knowl Synth Nurs. 2002;9:7. | |

Stetler CB. Role of the organization in translating research into evidence based practice. Outcomes Manag. 2003;7(3):97–105. | |

Rycroft-Malone J. The PARIHS Framework: a framework for guiding the implementation of evidence-based practice. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004;19(4):297–304. | |

Dearmon V, Roussel L, Buckner EB, et al. Transforming care at the bedside (TCAB): enhancing direct care and value-added care. J Nurs Manag. 2013;21(4):668–678. | |

American Nurses Credentialing Center. Magnet Recognition Program Model; 2014. Available from: http://www.nursecredentialing.org/Magnet/ProgramOverview/New-Magnet-Model. Accessed February 1, 2015. | |

National Institutes of Nursing Research. Bringing Science to Life: NINR Strategic Plan. National Institute of Nursing Research; 2011. Available from: http://www.ninr.nih.gov/sites/www.ninr.nih.gov/files/ninr-strategic-plan-2011.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2015. | |

Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–340. | |

Titler M. Impact of system-centered factors, and processes of nursing care on fall prevalence and injuries from falls. Robert Wood Johnson Interdisciplinary Nursing Quality Research Initiative 62597. PI: M. Titler. 2007: Funded September 2007–August 2009. | |

Meyer AD, Goes JB. Organizational assimilation of innovations: a multilevel contextual analysis. Acad Manag J. 1988;31(4):897–923. | |

Miles MB, Huberman AM. An Expanded Sourcebook: Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1994:183. | |

Tripp Reimer T, Deobbeling B. Qualitative perspectives in translational research. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(S1):S65–S72. | |

Cummings G, Estabrooks C, Midodzi W, Wallin L, Hayduk L. Influence of organizational characteristics and context on research utilization. Nurs Res. 2007;46(Suppl 4):S24–S39. | |

Kent B, Hutchinson AM, Fineout-Overholt E. Getting evidence into practice-understanding knowledge translation to achieve practice change. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2009;6:183–185. | |

Schultz AA. Clinical scholars at the bedside: an EBP mentorship model for today. Onlin J Excel Nurs Knowl. 2005;2–9. | |

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health Care System For The 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. | |

Dopson S, Fitzgerald L. The role of the middle manager in the implementation of evidence-based health care. J Nurs Manag. 2006;14:43–51. | |

Titler M. Translation science and context. Res Theory Nurs Pract Int J. 2010;24(1):35–46. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.