Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 14

Explanatory Models for Mental Distress Among University Students in Ethiopia: A Qualitative Study

Authors Negash A, Ahmed M, Medhin G, Wondimagegn D, Pain C, Araya M

Received 14 September 2021

Accepted for publication 12 November 2021

Published 27 November 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 1901—1913

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S338319

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Assegid Negash,1,2 Matloob Ahmed,1 Girmay Medhin,3 Dawit Wondimagegn,1 Clare Pain,4 Mesfin Araya1

1Department of Psychiatry, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2Department of Psychology, Wolaita Sodo University, Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia; 3Aklilu Lemma Institute of Pathobiology, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 4Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Correspondence: Assegid Negash Email [email protected]

Background: Socio-culturally determined processes account for how individuals give meanings to health, illness, causal attributions, expectations from treatment, and related outcomes. There is limited evidence of explanatory models for mental distress among higher education institutions in Ethiopia. The objective of this study was to explore the explanatory models for mental distress among Wolaita Sodo University.

Methods: The current study used a phenomenological research approach, and we collected data from 21 students. The participants were purposively recruited based on eligibility criteria. Semi-structured interviews were conducted from December 2017 to January 2018 using the Short Explanatory Models Interview. The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed into the Amharic language and translated into English. Data were analyzed using framework analysis with the assistance of open code software 4.02.

Results: Most students experienced symptoms of being anxious, fatigue, headaches and feelings of hopelessness. They labeled these symptoms like anxiety or stress. The most commonly reported causal explanations were psychosocial factors. Students perceived that their anxiety or stress was severe that mainly affected their mind, which in turn impacted their interactions with others, academic result, emotions and motivation to study. Almost all the students received care from informal sources, although they wanted to receive care from mental health professionals. They managed their mental distress using positive as well as negative coping strategies.

Conclusion: The policy implication of our findings is that mental health interventions in higher education institutions in Ethiopia should take into account the explanatory models of students’ psychological distress.

Keywords: explanatory models, mental distress, university students, Ethiopia

Introduction

University students experience mental distress (anxiety and depression) more frequently as compared with the general population.1 This could in part be attributed to their youth making them more vulnerable to mental distress, academic pressure within university, the stress and strangeness of being away from home for the first time, new peer relationships, and lower social support.1–3 However, most of these students do not access professional mental health services,4 perhaps because local explanatory models of suffering prevail and resonate more strongly than formal western biomedical understandings of mental distress.5,6

Explanatory models describe the way people with mental distress conceptualize their distress, explanations they give for causes, the modes of expression of distress, how they rate the severity of the problem, its onset, help-seeking behavior, coping mechanisms, treatment preference, and the adverse consequences of their distress.7 Explanatory models of mental distress are not static entities; they are fluid and multilayered that are caused by cultural and live experiences of patients.8 Students worldwide do not conceptualize mental distress based on biomedical models8 because of cultural belief and social contexts.9 Culture is a lens through which people perceive and interpret their world.10 Therefore, the complex cultural explanations available to students are inevitable form and influence how they understand their psychological distress and its causes.9,11

University students find it difficult to recognize symptoms of anxiety as mental distress when compared with depression, which they more readily concede as distressing. They experience symptoms of anxiety as feeling nervous, and feeling of apprehension in their day-to-day activities, as a normal and to be expected.12 However, they recognize symptoms of depression like sleeping difficulties, aggression, headaches, poor concentration, feeling sad, feeling down, feeling lonely, and hopeless.12–17 They attribute their distress to grief, parental divorce, interactional difficulties, family history of mental illness, feelings of loneliness and isolation, school work, economic problem, time management, parental expectations, and negative life events.13,18,19 Altogether, these causal factors can determine the help-seeking behavior of students and the impacts of mental distress.

Previous studies in Ethiopia have found most students are interested in using professional mental health care.20 However, a number of them do not receive mental health care despite its availability.21 A significant number of these students receive help from informal sources, such as family, friends, relatives, herbalists, and religious leaders.22 As well, the coping styles of students can be more or less helpful in managing their distress. An increase in severity of mental distress and lack of access to professional mental health care are associated with adverse effect on students’ academic achievement, physical health, emotion, self-esteem, social relationships, cognitive development, and their overall quality of life.13,16,23–26

In previous qualitative studies, adolescents used several coping strategies to manage mental distress.13,17,26 These include: support-seeking from others, social isolation, problem-solving, distraction, changing negative thoughts, acceptance, minimization, redirecting of aggression into a powerless substitute target, emotional discharge, positive appraisal, trying to forget uncomfortable feelings and thoughts, leaving a distressing situation, crying, self-harm behavior, suicide attempts, violence, prayer, listening to music, and substance use.13,17,26–29 Students also use meditation, telling oneself that everything will be “okay”, doing physical exercise, eating more, sleeping less, procrastination, and increased use of internet as a coping mechanisms from mental distress.30,31

Despite the existence of a few studies exploring explanatory models for mental distress in the general population, to the best of our knowledge, there is no published study that explored the explanatory models for mental distress among university students in Africa. We believe that taking into account the explanatory models of mental distress among university students in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is one pre-condition to sustainably tackle the alarming increase in anxiety and depression.2 Our study aimed to investigate the explanatory models for mental distress used by undergraduate students at Wolaita Sodo University.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting and Context

We carried out the current study at Wolaita Sodo University, which is one of the public Ethiopian universities located in Wolaita Sodo town of Wolaita zone, Southern Nations, Nationalities and People Regional State. This zone hosts multi-ethnic people that live harmoniously together. The societies in this zone are composed of 200 clans, and similar clans do not marry each other.32 It is the most densely populated area in Ethiopia. Wolaita zone covers a total area of 4541 km2 with an estimated population of 1,527,908, of whom 752,668 are males and 775,240 are females.33 Wolaita zone has 12 districts and three towns that are structured for administrative purpose. Wolaita Sodo is the capital town and economic and political center of the zone located 320 km south of Addis Ababa through Butajira. The main source of livelihood for the majority of city dwellers is trade, whereas agriculture is the main economic source for the rural people. The majority of the people are Evangelical Protestant Christians.

Wolaita Sodo University was established in 2007 G.C. and began its work with an intake of 801 students (609 male and 192 female) in four faculties and sixteen departments. It now has undergraduate and graduate programs in six colleges and five schools with more than 1300 academic staff and 2500 support staff. At the time of data collection, the University had 7321 male and 4707 female registered under graduate students. Dedicated to providing quality education, Wolaita Sodo University has been fully engaged in conducting research and delivering community services.

The university has health service facilities, including four full-time counselors (psychologists at Master’s and Bachelor’s degree level) with four counseling offices established to provide free counseling services for students with mental health and psychosocial problems. Three of the counselors are male and one is female. The University has also established a new center called “the mental health and psychosocial support for university students” designed to help students with Corona-virus-related issues. Apart from this, WSU has a referral teaching hospital (named the Otona hospital) that provides health care services, including outpatient and inpatient psychiatric care for the surrounding community and the students. The University has a students’ clinic that provides healthcare services for students and works closely with the students’ counseling offices. This clinic has a referral system with the Otona hospital for students with severe physical and mental illnesses.

Although the University has healthcare facilities, the majority (70.5%) of students with mental health problems did not receive professional mental healthcare.21 This is due to barriers associated with: (i) thinking the problem would get better with no intervention; (ii) preferring self-medication; (iii) denying a mental health problem existed; (iv) preferring to get alternative forms of mental care (religious leaders, friends, families, traditional healers, relatives, etc.); and (v) lack of information about the counseling offices in the university.21 Near the university, there are churches and mosques, where both Christian and Muslim students pray to their God or Allah, respectively; such practice might foster their religious coping mechanism from mental distress. On the contrary, there are shops and hotels that sell Khat, cigarettes, and alcohol without any restriction. Students can easily access these psychoactive drugs from the surrounding environment, although the WSU does not allow them to use these substances within its compound. The accessibility of psychoactive drugs near the university might create a conducive environment for mentally distressed students to use them as a coping strategy. See Figure 1 below.

|

Figure 1 Geographical location of the study area. |

Study Design

Interpretive phenomenological research design was employed to explore the meaning of lived experiences of students toward conceptualization, perceived symptoms and causes, help-seeking behavior, severity, onset pattern, coping mechanisms, and impacts of mental distress.34 Constructivism philosophical perspective that favors the “emic” or insider (as opposed to the “etic” or outsider observation) approach was used to guide this study based on the idea that mentally distressed students have their understanding of their mental distress35 that was derived from perceptions, experiences and actions concerning social contexts.36

Participants

The study participants were regular undergraduate university students who were pursuing their education at WSU. They were from different departments with a university year duration ranging from I–V. The participants were diversified in terms of culture, religion, area of origin, sex, marital status, and ethnicity. They were economically dependent on their family income. All participants were assessed positive to mental distress in our previous published study aimed to study the prevalence of mental distress,21 and they have received counseling service with close follow-up at Wolaita Sodo University counseling office given by the principal author of this study who has a Bachelor’s degree in Psychology, a Master’s degree in Counseling Psychology, has two years of counseling experience in the WSU counseling office and has attended the theoretical and practical training of IPT-E given by the manual adaptors.

Data Collection Instruments

Demographic information of the participants, including sex, age, religion, ethnicity, marital status, current place of living, origin, university year, and monthly pocket money, were collected. Mental distress was assessed using SRQ-20.37 SRQ-20 is a twenty yes/no item screening tool, which is widely used in LMICs to determine mental distress21 and it has been validated for use amongst the Ethiopian population.38,39 In the present study, a cut-off point of ≥8 on SRQ-20 was used to screen students with mental distress based on a previous validation study in Ethiopia.39 SRQ-20 is available in our previously published study.21 ing

The explanatory models for mental distress were explored using SEMI, which was developed from Kleinman’s original concept.7 This instrument has been translated into different languages to explore the “emic” perspective of distress using semi-structured open-ended questions.40,41 SEMI is a simple brief instrument. Furthermore, it consists of non-technical words, easily translated, and any interviewer from any background can administer it after receiving training to use it.42 According to Azale et al,43 SEMI was adapted to an Ethiopian context by an expert consensus meeting involving mental health professionals and qualitative researchers. It has seven sections that cover perceived symptoms, conceptualization, perceived causes, perceived severity, impacts, help-seeking behaviors, and coping mechanisms of mental distress. The face-to-face interview was conducted in Amharic language by the principal author in a private and well-ventilated students’ counseling room of Wolaita Sodo University. The participants were encouraged to talk openly about their experiences. Probing was done to further elicit and explore ideas of mental distress. The interviews were audio-recorded with consent. The average duration of the 21 interviews was 42 minutes ranging from 21 to 118 minutes.

Sampling Procedures

The study participants were recruited from study one that aimed to assess the prevalence of mental distress among university students,21 which was conducted from December 2017 to January 2018. In the screening phase of the prevalence study, participants were informed that if they experience any symptoms of mental distress and volunteer to receive professional psychological support, they can write their phone number in the middle page of Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20) or they can contact the first author of this article in person. In this process, 29 volunteer students wrote their cell phone number. Of these, 21 (72.4%) students were contacted using their cell phone and following written consent; they voluntarily participated in the interview. The eligibility criteria for the current study were: being undergraduate student; scoring 8 or more on SRQ-20; willingness to participate in the study; and 18 years or older. The remaining eight students did not answer their phones when they were called. Redundancy of answers to the Short Explanatory Model Interview (SEMI) was an indicator of information saturation, indicating that the maximum number of participants was sufficient for the present qualitative study.44

Data Analysis

The audio taped interviews were transcribed into Amharic. The transcribed data were translated into the English language by the first author (AN). Framework analysis was chosen over the other qualitative analysis methods.45 This analysis method emphasizes how both prior issues and emergent data-driven themes should guide the development of the analytic framework.46 This approach fits better with the aim of the current study. The predetermined themes in the SEMI are designed to explore the lived experiences of university students with mental distress, and we were open to discovering new emerging theme/s. The other justification for the use of framework analysis is that it is suitable for the analysis of our data generated based on the basic research question, “what are university students’ explanatory models for mental distress?” and compatible with the interpretive phenomenological research design.

In the process of using the framework analysis, we followed five sequential steps. These steps were as follows: immersing one’s self with the audio-recorded interviews (listening carefully) and transcribing the data by reading again and again (familiarization), identifying a framework, indexing (coding), charting (summarizing), and interpreting the result.46 Great attention was given during coding of the data because the coded information should capture the meaning of what the participants exactly said. To ensure this, five translated interviews were coded by the first author and another experienced qualitative researcher independently to check inter-rater coding reliability that resulted in almost similar codes. The first author then coded all the remaining interviews alone. Predetermined themes were identified. We have used a free open code version 4.0247 to facilitate the analysis that enabled us to manage data.

Trustworthiness

Rigor in a qualitative research is highly related to the trustworthiness of the work done in a specific study that includes credibility, dependability, conformability, and transferability.48 To ensure the credibility of our work the following were done: (a) what we did: the data collection instrument was carefully designed to elicit and generate data; (b) prolonged familiarization with the data was passed through steps of interviewing, transcribing, and translation; and (c) five randomly selected translations were coded by the principal author of this article and one expert who knew the subject matter of the study so as to ensure the accuracy of the codes. The whole process and the tasks performed in the present study were supervised and reviewed by senior co-authors of this study (MA, MK, GM, DW, and CP) to confirm the dependability and conformability of the current study. All the necessary files are available and indicate the transferability of our study findings to other settings.

Results

Information collected from 21 study participants was analyzed, and the key findings were elaborated under seven themes that include: (a) perceived symptoms, (b) conceptualization of mental distress, (c) perceived causes, (d) perceived severity, (e) impacts, (f) help-seeking behaviors and (g) coping mechanisms from mental distress. The participants were composed of five female and sixteen male students with a mean age of 21 years (SD = 1.71; range = 19–25 years). The majority of the participants were Orthodox Christian by religion, from the Amhara ethnic group and single. All participants lived in the University residence. More than half of the participants were from an urban background and were first-year students. The average monthly pocket money received from their family was 501 Ethiopian Birr (ETB) (range = 50–1000 ETB). All students scored positive for mental distress with a mean SRQ-20 score of 13.38 (SD = 2.78; range = 8–20). See Table 1 below.

|

Table 1 Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants with SRQ-20 Score Above the Cut-off Point (n = 21) |

Perceived Symptoms of Mental Distress

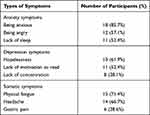

Most participants experienced a mixture of symptoms of anxiety, depression and somatic disorders (Table 2). The most commonly reported complaints were: being anxious, physically fatigued, headache, and feeling of hopeless. The following two illustrative quotes captured these chief complaints.

Yeah, immediately when I sat in the classroom, I became anxious. I did not know that it was because of anxiety. When I go to church, I cannot stay until the church ceremony is finished, because of the headache. When I start to read, I become mentally unstable and then, I cannot open my two eyes, but after a few minutes my eyes become open; then after I started to read for a few minutes again my eyes become closed and A letter seems to me B. I feel tired, my body gets feeling of burning, and I also get joint pain … When my gastric get start, I cannot eat food and I feel pain in the stomach. I try to sleep but I cannot sleep due to the serious headache. (A 22-year-old female, in a relationship)

|

Table 2 Types and Frequency of Chief Complaints |

Other students explained that:

I feel extreme hopelessness. I cannot properly concentrate on my education because of lack of motivation I have. I consider life as meaningless. (A 20-year-old female, single)

Psychological problem cannot bring any problem, so I said to you, I am very happy to see the end of this world by being a mad person. Previously I had a hope to long live and had fear of death. But now, I know that if I am a mad person, I can survive so that why should I worry? (A 20-year-old male, single)

Conceptualization of Mental Distress

Eight and four participants labeled their problems as anxiety and stress, respectively. The interviewer also asked the participants how long the problem had lasted. Five students were suffering for a year; four students had their problems for three years and another five students reported that their distress started six months ago. Five students reported that their distress started two and four years ago. The remaining two students reported their problem had been with them since elementary school.

I think this case is related with mental abnormality, specifically it is anxiety. It (my problem) started before six months. (A 25-year-old male, single)

Another student explained that:

I don’t know; it is difficult for me to give a name. But, I guess stress can express it. I started to experience the problem three years ago. (A 22-year-old male, single)

One student named her problem as evil spirit.

As to me, the name of my problem is (bad spirit); it is the one who enforce me to conflict with my friends without having any reason and it is he (bad spirit) who changes my behavior and mood within a short period of time. When I was in elementary school, I have been experiencing this problem. (A 22-year-old female, in a relationship)

Causal Factors for Mental Distress

When participants asked about how their psychological distress began, they commonly reported mixed causes related to social causes: such as education difficulties and workload (14/21), economic problems (8/21), family related issues such as conflict and loss (6/21), conflict with friends (3/21), psychological causes such as “thinking too much” (7/21), adjustment to the new environment (life changes) (4/21), mismatch of expectations (4/21), and love-related issue (3/21).

Yeah, the main reasons for my illness are: thinking too much about what to do after graduation, because I am not equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills. Second, as I have told you before, my mother and father were died and the only source of support by this time is only my sister. She is not economically strong enough (hand to mouth) and she is uneducated. So, I always think about how I can change her life. She sacrificed a lot for my life starting from early childhood; she expects more from me after graduation. You know when I face a shortage of money; I do not want to ask her, because I know her economic capacity. The third is difficulty of education. While I am thinking all about these issues, I become anxious and I start to think I am living meaningless life. Internally, I have a lot of unresolved issues. (A 22-year-old male, single)

Perceived Severity of Mental Distress

More than half (12/21) of the participants perceived that their distress was very severe, and they feared that their distress would become yet more severe. The remaining respondents rated their problem as mild (6/21) and moderate (3/21).

It (the distress) is very severe problem, even by this time I dislike learning. Can you believe that in our dorm, there are 32 freshman students and in every night they sing a song; when you inform them to stop disturbing, their response is do you want to control us while we are living more than 30 students together in a single class? When you think all these things, you prefer to leave the campus, but what can you do when your families are poor and live in rural area. (A 20-year-old male, single)

Impacts of Mental Distress

Participants were asked an open-ended question concerning the difficulties that the distress caused them. Most of them replied that their distress adversely affected the interaction with other people (causing conflict with family and friends), reduced academic achievement, caused them to feel sad and angry and reduced their motivation to work (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Consequences of Experiencing Mental Distress |

Help-Seeking Behaviors and Intention to Seek Professional Mental Health Treatment

Most of the participants received care from multiple informal sources, such as friends (12/21, advice) and religious leaders (4/21, holy water, fasting, and praying) and family (4/21, advice). Only three students received professional mental healthcare. However, all participants intended to receive mental healthcare from professionals because they were afraid their distress would worsen with time.

Yes, I have received advice from religious leaders. The religious leaders understood that the problem is related with bad spirit and they ordered me not to be far from the church and to drink and sprinkle holy water, fast, and prayer. The religious leaders also advised me not to give-up, worry, anxious. Moreover, my friends advised me not to worry that nothing will happen on me and to go to church regularly. I need help if the problem has a solution, because I have fear. From the things that I fear all the time, I may not be with my friends all the time. One day I may go somewhere alone and at that time, I cannot properly manage myself so that the problem can throw me into abysm or burrow. (A 22-year-old female, in a relationship)

Coping Strategies

Under this theme, there were two sub-themes: positive and maladaptive coping strategies that students used to manage their mental distress. Attending church, discussing with friends, listening to music and watching a film were the most commonly reported positive coping strategies. On the other hand, sleeping for a long time was amongst the most commonly reported negative coping strategy (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Coping Strategies to Manage Mental Distress |

Based on the qualitative findings, a conceptual framework for explanatory models of mental distress was developed. The model shows a link among the explored constructs. As it can be observed in Figure 2, the psychosocial factors caused students to experience mental distress that was mainly manifested by psychological and somatic symptoms. This mental distress impacted students’ emotions, motivation, relationships with others and educational outcomes. The impact of mental distress was the fear that it could become more severe in future, which led the students to need professional mental health services, despite using coping strategies and receiving support from informal sources to manage the problem.

|

Figure 2 Conceptual framework of explanatory models of mental distress. |

Discussion

In this qualitative study, anxiousness, fatigue, headache, and hopelessness were the most commonly reported complaints by university students. Most of the participants labeled these complaints as anxiety or stress. The most commonly reported causal explanations were related to social and psychological issues. More than half of the participants perceived their mental distress as a severe problem. Most students reported that the onset of their mental distress ranged from two months to four years. Their mental health problem mainly affected their head which in turn had significant negative impacts on their interaction with other people, their academic achievement, emotions, and motivation to work. Almost all participants received care for their mental distress from informal sources and all of them had the intention to receive mental health care from professionals because they feared their distress would worsen with time. Participants reported that they managed their mental distress by using both positive and negative coping strategies.

Most of the students conceptualized their mental health problems in terms of psychological and somatic symptoms. The most frequently reported psychological symptoms were being anxious and feeling of hopelessness, which are also used as diagnostic features of anxiety and depression, respectively, in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).49 Although there is a difference in a context in the present study, these symptoms have been previously identified in LMICs and in high-income country where most adolescents elaborated their distress by feeling of anxiety26 and lack of hope.50 Other frequently reported complaints in the current study were physical fatigue and headaches that are recognized as diagnostic criteria for depression and anxiety, respectively.49 Somatization of mental distress is common worldwide, for example, in many African countries,51 in Oman,52 in Iran,53 and in India54 people with anxiety and depression express their distress in terms of medically unexplained symptoms. The expression of mental distress in terms of somatic symptoms is a complex question and might be linked among other things to fear of public stigma55 and cultural influences.9

Most of the students labeled both psychological and somatic symptoms as a manifestation of anxiety or stress. Although the context is different, a similar result is also found in Vietnam, where most students labeled depression symptoms as stress or anxiety.56 Being able to give a specific psychiatric term to the complaints may be because of the students’ educational status, which may have influenced their mental health literacy; the symptoms of anxiety and stress are very common among university students and considered as normal life challenges.12 Most students attributed their mental distress to more than one causal factor; similarly, in North Western Ethiopia57 and Kenya,58 most participants reported psychosocial explanations as causes for their mental health problem. Of the causal factors, students reported more education-related issues. These academic stressors are associated with heavy academic loads, exam difficulty,59 difficulty with assignments,28 and the time constraints required by courses.52 Previous studies also found that most university students’ major stressor for mental health problem was linked to educational stressor.18,60

The next most commonly reported social causes were economic problem and interpersonal difficulties. Most of the students who join university in Ethiopia encounter economic challenges. This is especially more challenging for students from rural background, because of: (a) their family assumes that if their student joined in a university, they expect every cost of the student is covered by the university, but the reality on the ground is that a public university in Ethiopia covers only students’ food, dormitory, and medication cost with a cost-sharing system; (b) almost all undergraduate students in Ethiopia are economically dependent on their families’ income; and (c) there is difficulty of accessing bank and telecommunication services for students who come from rural areas. The inability to receive money from families in a timely way can cause mental distress; the death of a family member who was the main breadwinner for the family again creates mental distress for the student involved. Similar studies have shown that poverty and conflict within the family are causal factors for psychological distress.28,60–62

In the present qualitative study, more than half the students reported that their mental distress was very severe. This in turn affected their interactions with others, their academic achievement, their emotional state, and their motivation to work. In prior studies, most participants reported that their mental distress was severe51 and negatively affected their social interaction,25 feeling,53 education result,13,52,63 and appetite for work.64 Students reported different coping strategies to manage their mental distress. Of these, getting social support from friends, attending church, and listening to music and watching a film were among the positive coping styles that used to recover and get relief from mental distress without causing negative health effects, which were also reported in the previous studies.13,17,18,28,60,65,66 On the contrary, sleeping for a long time was commonly reported as an unhealthy coping mechanism that could harm students’ education and health outcomes. The use of maladaptive coping strategies by the students might be caused by feeling hopelessness67 or associated with unable to control their mental distress.68 Apart from seeking help from friends, religious leaders, and family, all students wished to receive mental healthcare due to fear and increasing severity of the distress from time to time. This might indicate how their problem is severe because most adolescents perceive help from professionals as a last resort and a sign of weakness.13

Limitations

All research has its limitations, and the present study is not limitations-free. First, the data collected using self-reported questionnaires might have involved recall bias. Second, the face-to-face interview might be prone to social desirability bias when reporting negative coping strategies. Third, most participants were male and female students’ perceived explanatory models for mental distress are likely to be under-represented.

Conclusions

Most students perceived their mental distress in terms of psychological and somatic symptoms, most of them recognized their complaints as anxiety or stress that caused psychosocial factors. Most students perceived their distress as severe and affected their education and social interactions. Therefore, first, we recommend that exploring the explanatory models for mental distress among university students must be part of understanding the students’ needs for mental healthcare and support and implementing locally acceptable and feasible evidence-based mental health intervention/s. Second, mental health professionals working in the university hospital, student clinic, and student counseling offices are expected to sufficiently access their mental health services to students with mental distress to reduce the burden of the problem.

Abbreviations

LMICs, low- and middle-income countries; SRQ, self-reporting questionnaire; SEMI, Short Explanatory Model Interview; SD, standard deviation; DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; ETB, Ethiopian Birr.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable requests.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

Ethical clearance approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Addis Ababa University College of Health Sciences with a protocol number of 045/17/Psy. All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study after they had received clarification about the objective of the study and received an information sheet. The participants’ informed consent included publication of anonymized responses. They were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time if they were not comfortable participating in the study, without prejudice. Concerning tracing the participants using their cell phone number, they were well informed about the availability of the counseling service given by mental health professional, if they need in our previous screening study;21 then, they convinced and consented to receive mental health intervention so that they wrote their cell phone number in the middle of the mental distress screening tool. Then, the principal author of this study provided the counseling service for all participants involved in this study. The questionnaire that contained the participants’ cell phone numbers was kept in a locked box of the principal author’s house to keep confidentiality. The collected data were kept anonymous and confidential during all the stages of the study. Besides, this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles for medical research involving human participants.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Addis Ababa University and Wolaita Sodo University for funding and material support. We also want to thank research participants for their active participation and time.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study is funded by Addis Ababa University and Wolaita Sodo University. These funders had no role in the study design; data collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in writing the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

References

1. Stallman HM. Psychological distress in university students: a comparison with general population data. Aust Psychol. 2010;45(4):249–257. doi:10.1080/00050067.2010.482109

2. Evans‐Lacko S, Thornicroft G. World Health Organization world mental health surveys international college student initiative: implementation issues in low‐and middle‐income countries. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2019;28(2):e1756. doi:10.1002/mpr.1756

3. Hefner J, Eisenberg D. Social support and mental health among college students. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79(4):491–499. doi:10.1037/a0016918

4. Eisenberg D, Golberstein E, Gollust SE. Help-seeking and access to mental health care in a university student population. Med Care. 2007;594–601. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31803bb4c1

5. Ghane S, Kolk AM, Emmelkamp PM. Assessment of explanatory models of mental illness: effects of patient and interviewer characteristics. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(2):175–182. doi:10.1007/s00127-009-0053-1

6. Waite R, Tran M. Explanatory models and help-seeking behavior for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among a cohort of postsecondary students. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2010;24(4):247–259. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2009.08.004

7. Kleinman A. Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture. University of California press; December 31, 1980.

8. Kirmayer LJ, Bhugra D. Culture and mental illness: social context and explanatory models. In: Psychiatric Diagnosis: Patterns and Prospects. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2009:29–37.

9. Dinos S, Ascoli M, Owiti JA, Bhui K. Assessing explanatory models and health beliefs: an essential but overlooked competency for clinicians. BJPsych Adv. 2017;23(2):106–114. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.114.013680

10. Okello ES. Cultural Explanatory Models of Depression in Uganda. Karolinska University Press; 2006.

11. Petkari E. Explanatory models of mental illness: a qualitative study with Emirati future mental health practitioners. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2015;18(9):738–752. doi:10.1080/13674676.2015.1091447

12. Perre NM, Wilson NJ, Smith-Merry J, Murphy G. Australian university students’ perceptions of mental illness: a qualitative study. J Aust N Z Stud Serv Assoc. 2016;24(2):1092.

13. Weitkamp K, Klein E, Midgley N. The experience of depression: a qualitative study of adolescents with depression entering psychotherapy. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2016;3:2333393616649548. doi:10.1177/2333393616649548

14. Fornos LB, Seguin Mika V, Bayles B, Serrano AC, Jimenez RL, Villarreal R. A qualitative study of Mexican American adolescents and depression. J Sch Health. 2005;75(5):162–170. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.tb06666.x

15. Midgley N, Parkinson S, Holmes J, Stapley E, Eatough V, Target M. Beyond a diagnosis: the experience of depression among clinically-referred adolescents. J Adolesc. 2015;44:269–279. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.08.007

16. McCann TV, Lubman DI, Clark E. The experience of young people with depression: a qualitative study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2012;19(4):334–340. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01783.x

17. Majumdar B, Ray A. Stress and coping strategies among university students: a phenomenological study. Indian J Soc Res. 2010;7(2):100–111.

18. Graf H, Melton B, Gonzalez S, Qualitative A. Study of stressors, stress symptoms, and coping mechanisms among college students using nominal group process. J Ga Public Health Assoc. 2010;5(1):24–37.

19. Khalid A, Qadir F, Chan SW, Schwannauer M. Adolescents’ mental health and well-being in developing countries: a cross-sectional survey from Pakistan. J Ment Health. 2019;28(4):389–396. doi:10.1080/09638237.2018.1521919

20. Alemu Y. Perceived causes of mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among university students in Ethiopia. Int J Adv Couns. 2014;36(2):219–228. doi:10.1007/s10447-013-9203-y

21. Negash A, Khan MA, Medhin G, Wondimagegn D, Araya M. Mental distress, perceived need, and barriers to receive professional mental healthcare among university students in Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):1–5. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02602-3

22. Gebreegziabher Y, Girma E, Tesfaye M. Help-seeking behavior of Jimma university students with common mental disorders: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0212657. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212657

23. Field T, Diego M, Pelaez M, Deeds O, Delgado J. Depression and related problems in university students. Coll Stud J. 2012;46(1):193–202.

24. Ryan ML, Shochet IM, Stallman HM. Universal online interventions might engage psychologically distressed university students who are unlikely to seek formal help. Adv Ment Health. 2010;9(1):73–83. doi:10.5172/jamh.9.1.73

25. Rickwood D, Deane FP, Wilson CJ, Ciarrochi J. Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Aust e-J Adv Ment Health. 2005;4(3):218–251. doi:10.5172/jamh.4.3.218

26. Spencer S, Stone T, Kable A, McMillan M. Adolescents’ experiences of distress on an acute mental health inpatient unit: a qualitative study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2019;28(3):712–720. doi:10.1111/inm.12573

27. Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Barreto M, et al. Coping with loneliness at university: a qualitative interview study with students in the UK. Ment Health Prev. 2019;13:21–30. doi:10.1016/j.mhp.2018.11.002

28. Deasy C, Coughlan B, Pironom J, Jourdan D, Mannix-McNamara P. Psychological distress and coping amongst higher education students: a mixed method enquiry. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115193. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115193

29. Aselton P. The Lived Experience of College Students Who Have Been Medicated with Antidepressants. University of Massachusetts Amherst; 2010.

30. Dan Cordrey RN, David Floyd RNBS, Lindsey Grubbs RN, Sarah Miller RNBS, Brooks Tyre RNBS. Stress: perceptions, manifestations, and coping mechanisms of student registered nurse anesthetists. AANA J. 2012;80(4):S49.

31. Dexter LR, Huff K, Rudecki M, Abraham S. College students’ stress coping behaviors and perception of stress-effects holistically. Int J Stud Nurs. 2018;3(2):1. doi:10.20849/ijsn.v3i2.279

32. Hidoto Y. Cattle counting ceremony among the Wolaita (Ethiopia): exploring socio-economic and environmental roles. Open J Ecol. 2015;5(05):159. doi:10.4236/oje.2015.55014

33. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission. Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census Results. Addis Ababa; 2008.

34. Sloan A, Bowe B. Phenomenology and hermeneutic phenomenology: the philosophy, the methodologies, and using hermeneutic phenomenology to investigate lecturers’ experiences of curriculum design. Qual Quant. 2014;48(3):1291–1303. doi:10.1007/s11135-013-9835-3

35. Honebein PC. Seven goals for the design of constructivist learning environments. In: Constructivist Learning Environments: Case Studies in Instructional Design. New York, NY; Simon & Shchuster Macmillan; 1996:11–24.

36. Tolley EE, Ulin PR, Mack N, Robinson ET, Succop SM. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A field Guide for Applied Research. John Wiley & Sons; May 9, 2016.

37. van der Westhuizen C, Wyatt G, Williams JK, Stein DJ, Sorsdahl K. Validation of the self reporting questionnaire 20-item (SRQ-20) for use in a low-and middle-income country emergency centre setting. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2016;14(1):37–48. doi:10.1007/s11469-015-9566-x

38. Hanlon C, Medhin G, Selamu M, et al. Validity of brief screening questionnaires to detect depression in primary care in Ethiopia. J Affect Disord. 2015;186:32–39. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.07.015

39. Youngmann R, Zilber N, Workneh F, Giel R. Adapting the SRQ for Ethiopian populations: a culturally-sensitive psychiatric screening instrument. Transcult Psychiatry. 2008;45(4):566–589. doi:10.1177/1363461508100783

40. Sumathipala A, Siribaddana S, Hewege S, Sumathipala K, Prince M, Mann A. Understanding the explanatory model of the patient on their medically unexplained symptoms and its implication on treatment development research: a Sri Lanka Study. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8(1):1. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-8-54

41. Jacob KS, Bhugra D, Lloyd KR, Mann AH. Common mental disorders, explanatory models and consultation behaviour among Indian women living in the UK. J R Soc Med. 1998;91(2):66–71. doi:10.1177/014107689809100204

42. Mirza I, Hassan R, Chaudhary H, Jenkins R. Eliciting explanatory models of common mental disorders using the Short Explanatory Model Interview (SEMI) Urdu adaptation–a pilot study. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56(10):461–463.

43. Azale T, Fekadu A, Hanlon C. Treatment gap and help-seeking for postpartum depression in a rural African setting. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):1. doi:10.1186/s12888-016-0892-8

44. Mack N. Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector’s Field Guide. Family Health International. 2005.

45. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

46. Parkinson S, Eatough V, Holmes J, Stapley E, Midgley N. Framework analysis: a worked example of a study exploring young people’s experiences of depression. Qual Res Psychol. 2016;13(2):109–129. doi:10.1080/14780887.2015.1119228

47. Open Code 4.0. ICT Services and System Development and Division of Epidemiology and Global Health. Sweden: University of Umeå; 2013.

48. Ghafouri R, Ofoghi S. Trustworth and rigor in qualitative research. Int J Adv Biotechnol Res. 2016;7(4):1914–1922.

49. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub; May 22, 2013.

50. Willis N, Mavhu W, Wogrin C, Mutsinze A, Kagee A. Understanding the experience and manifestation of depression in adolescents living with HIV in Harare, Zimbabwe. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190423. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0190423

51. Patel V, Gwanzura F, Simunyu E, Lloyd K, Mann A. The phenomenology and explanatory models of common mental disorder: a study in primary care in Harare, Zimbabwe. Psychol Med. 1995;25(6):1191–1199. doi:10.1017/S003329170003316X

52. Jahan F, Siddiqui MA, Mitwally M, Al Zubidi NS, Al Zubidi HS. Perception of stress, anxiety, depression and coping strategies among medical students at Oman Medical College. Middle East J Fam Med. 2016;14(7):16–23. doi:10.5742/MEWFM.2016.92856

53. Dejman M, Forouzan AS, Assari S, et al. An explanatory model of depression among female patients in Fars, Kurds, Turks ethnic groups of Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2011;40(3):79.

54. Andrew G, Cohen A, Salgaonkar S, Patel V. The explanatory models of depression and anxiety in primary care: a qualitative study from India. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-5-499

55. Groleau* D, Kirmayer LJ. Sociosomatic theory in Vietnamese immigrants’ narratives of distress. Anthropol Med. 2004;11(2):117–133. doi:10.1080/13648470410001678631

56. Thai QC, Nguyen TH. Mental health literacy: knowledge of depression among undergraduate students in Hanoi, Vietnam. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2018;12(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/s13033-018-0179-1

57. Mulatu MS. Perceptions of mental and physical illnesses in north-western Ethiopia: causes, treatments, and attitudes. J Health Psychol. 1999;4(4):531–549. doi:10.1177/135910539900400407

58. Mbuthia JW, Kumar M, Falkenström F, Kuria MW, Othieno CJ. Attributions and private theories of mental illness among young adults seeking psychiatric treatment in Nairobi: an interpretive phenomenological analysis. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2018;12(1):1–5. doi:10.1186/s13034-018-0229-0

59. Carver CS, Connor-Smith J. Personality and coping. Ann Rev Psychol. 2010;61:679–704. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352

60. Al-Dubai SA, Al-Naggar RA, Alshagga MA, Rampal KG. Stress and coping strategies of students in a medical faculty in Malaysia. Malays J Med Sci. 2011;18(3):57.

61. Pereira B, Andrew G, Pednekar S, Pai R, Pelto P, Patel V. The explanatory models of depression in low income countries: listening to women in India. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1–3):209–218. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.025

62. Chinekesh A, Hosseini SA, Mohammadi F, et al. An explanatory model for the concept of mental health in Iranian youth. F1000Research. 2018;7. doi:10.12688/f1000research.12893.1

63. Al-Qaisy LM. The relation of depression and anxiety in academic achievement among group of university students. Int J Psychol Couns. 2011;3(5):96–100.

64. Keong P, Sern L, Lee M, Ibrahim C, editors. The relationship between mental health and academic achievement among university students–a literature review.

65. Mason HD. Stress-management strategies among first-year students at a South African University: a qualitative study. J Stud Aff Afr. 2017;5(2):131–149. doi:10.24085/jsaa.v5i2.2744

66. Gallagher KM, Jones TR, Landrosh NV, Abraham SP, Gillum DR. College students’ perceptions of stress and coping mechanisms. J Educ Dev. 2019;3(2):25. doi:10.20849/jed.v3i2.600

67. Landis D, Gaylord-Harden NK, Malinowski SL, Grant KE, Carleton RA, Ford RE. Urban adolescent stress and hopelessness. J Adolesc. 2007;30(6):1051–1070. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.02.001

68. Stallman HM, Lipson SK, Zhou S, Eisenberg D. How do university students cope? An exploration of the health theory of coping in a US sample. J Am Coll Health. 2020;1–7. doi:10.1080/07448481.2020.1789149

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.