Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 14

Experience of Polish Patients with Obesity in Contacts with Medical Professionals

Authors Sobczak K , Leoniuk K , Rudnik A

Received 4 July 2020

Accepted for publication 22 August 2020

Published 22 September 2020 Volume 2020:14 Pages 1683—1688

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S270704

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Krzysztof Sobczak, 1 Katarzyna Leoniuk, 1 Agata Rudnik 2

1Department of Sociology of Medicine & Social Pathology, Medical University of Gdansk, Gdansk, Poland; 2Institute of Psychology, University of Gdansk, Gdansk, Poland

Correspondence: Krzysztof Sobczak Email [email protected]

Purpose: Discrimination and stigmatization of patients with obesity are a commonly occurring social problem. The purpose of our research was to analyze the scale of the experience including medical staff’s improper behaviours towards patients with obesity in Poland.

Patients and Methods: In a completed national study, we studied the statements of 621 adult patients who suffer from obesity. An original closed question survey was used as a tool to collect the data. Patients were informed about the possibility to participate in the study through social media, medical institutions and patient foundations.

Results: As many as 82.6% have experienced improper behaviours. Usually, it came from doctors (90%), nurses and midwives (51%), people who operated medical equipment (24%), nutritionists (14%) and paramedics (9%). Exactly 81% of the respondents pointed to unpleasant and judgmental comments as the most frequent form of improper behaviour which they have encountered mainly during diagnostic tests, palpation or procedures.

Conclusion: There is an urgent need for developing national strategies connected with care for individuals with higher body weight. Introducing dedicated solutions in this field may contribute to increasing the quality of health care and reducing stigmatizing behaviours.

Keywords: stereotyping, social stigma, health beliefs, health behaviours

A Letter to the Editor has been published for this article.

A Response to Letter has been published for this article.

Introduction

Discrimination and stigmatization of people with obesity is, unfortunately, a noticeable problem in the societies of developed countries.1–4 There are many reports which document the prevalence of this phenomenon, also in health care institutions.5–9 Therefore, it can be supposed that the medical staff’s discriminative behaviours towards patients who have obesity are – just as obesity itself – a global problem.10 Importantly, during the research, we found a relationship between the experience of stigmatizing behaviour in contacts with medical personnel and the increase in BMI in people with severe obesity. Abusive treatment of an obese patient should be considered one of the barriers to recovery.11

According to various data, 17.2% to 24.7% of the Polish population is afflicted with obesity, regardless of gender.12,13 Despite such a large number of patients with obesity, there are only a few reports concerning the issue of medical staff’s declarative attitudes towards these patients.14–16 To the best of our knowledge, no national research has been undertaken so far that would illustrate the problem of stigmatization from the perspective of individuals with higher body weight.

Therefore, the purpose of our research was to determine the character of the relationship which occurs between patients with obesity and medical staff. In a national survey, we have asked this group of patients about their experience in relations with medical staff taking into account the indexes of comfort, communication and support they are receiving. Thanks to the results we have obtained, we would like to illustrate the attitudes of medical staff concerning the discussed issue. Our intention was also to compare the results which have been obtained with the results of analogous studies around the world.

Patients and Methods

Participants and Procedures

In total, 684 respondents participated in the survey. 90.8% of the survey forms, that is 621 patient statements, were qualified for analysis (Table 1). The statements of 63 respondents were rejected as they did not fulfil the inclusion criteria of BMI <30. We calculated the BMI value based on the data on height and weight provided by the respondents. The study was addressed only to adults aged 18 and over.

|

Table 1 Characteristics of Respondents (N=621) |

We obtained the quantitative data with CAWI techniques (Computer-Assisted Web Interview). The study was conducted in the period from February 2018 to March 2019. The first way of informing patients about the possibility to participate in the study was by ads and information in electronic (social?) media. They could also find out about the possibility to participate in the study through leaflets, which were made available by medical institutions and support groups for patients with obesity. When the study was beginning, the respondents were informed that they could abandon the study at any point. All respondents gave their informed and voluntary consent to participate in the study.

The research tool and the method used were approved by the Independent Bioethics Commission for Research at the Medical University of Gdansk.

Measures

An originally prepared survey questionnaire was our research tool. It was digitized and put on a professional website for conducting sociological research. The questionnaire was divided into three parts which, respectively, pertained to the analysis of the fields relating to the patient’s comfort, communication with medical staff, as well as information and emotional support. It consisted of 18 closed-ended questions and 11 questions concerning the patients’ sociodemographic status. The tool was scaled in a way which allows eliminating the problem of missing data in the answers and farming (a single respondent completing the survey several times) through automatically blocking IP of a device from which another request was sent for connecting with the server where the questionnaire was published.

Statistical Analysis

The gathered data were processed in the form of summary statistics with IBM SPSS v.26 software. In the analysis of correlations between discontinuous variables and statistic heterogeneity of the groups, we have used Pearson’s Chi-Square test. The value for p<0.05 was assumed as statistically important.17,18 We used the Chi-Square test of independence to examine the relationship between nominal variables: demographic, health, and a sense of discrimination.

Results

Experiences of Discrimination

Most of the respondents were of the opinion that patients with obesity were treated worse than those with normal weight (82.8%). The majority (82.6%) of the patients also revealed that they had experienced improper behaviour of medical staff. Such experiences were declared more frequently by women (85.2%) than men (64.9%; statistics: Chi^2=18.885; df=1; p<0.001) and patients with higher education (85.7%) than the rest (78.8%; statistics: Chi^2=5.105; df=1; p<0.0024).

The respondents revealed that most frequently such improper behaviours came from doctors (90%) as well as nurses and midwives (51%). Furthermore, patients indicated staff operating medical equipment (24%), administrative staff (16%), nutritionists (14%) and paramedics (9%). The fewest negative assessments were directed at physiotherapists (7%) and pharmacists (4%).

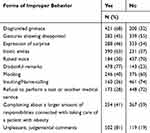

Forms of Discrimination

When asked about the forms of improper behaviour, patients most frequently pointed to unpleasant and judgmental comments (81%) which they had experienced from medical staff as well as disdainful remarks (Table 2). The respondents also admitted that they felt they had been blamed for carrying excess weight (73%) and it had been communicated to them in the form of threats that their health would predictably deteriorate (89%). They also heard statements about obesity being the reason why it was impossible to treat their other diseases (68%).

|

Table 2 Forms of Medical Staff’s Improper Behavior (N=621) |

Context of the Discrimination

We have also asked patients about the situations in which they most frequently experienced improper treatment by medical staff. The largest number of respondents (as many as 62%) reveals that they have experienced this kind of situations during diagnostic tests. Exactly 50% admitted that they were connected with palpation and medical procedures. On average, every fourth patient that we had questioned revealed that he or she had experienced discrimination during rehabilitation procedures (22%) and medical transport (18%).

Assessment of the Level of Support

At the same time, the group of patients who participated in our study was divided relatively proportionally when it came to the assessments of positive attitudes and messages from medical staff. Exactly 45% admitted that they had experienced support as well as expressions of care and understanding (49%) of their illness. Most of the patients (77%) revealed that they had experienced situations in which a member of the medical staff explained the necessity to reduce their weight in a neutral way.

Discussion

There is a significant shortage of research concerning the issue of discrimination. To the best of our knowledge, the presented studies are the first ones in the country to explore the experience of patients with obesity in relations with health professionals.

The few domestic reports concerning the discussed problem present the opposite perspective – the medical staff’s attitudes and assessments of individuals with higher body weight. Sińskia et al analyzed the opinions of 180 nurses in 2012. The results revealed that they were aware of the stigmatization. More than half of them (51%) agreed with the statement that patients with obesity were scruffy and had problems with personal hygiene, did not take care of their health (42%) or ignored medical recommendations. The same group expressed the opinion (48%), that patients with obesity were more difficult to cooperate with.16 Another study by the same author in which she analyzed the declarative opinions of doctors (N=100) and nurses (N=200) shows that medical staff declares a positive, friendly and empathic attitude to individuals with obesity in spite of the fact that 19.5% of the nurses and 23% of the doctors who participated admitted they felt negative emotions just at the sight of a patient with higher body weight. Most of the nurses (72%) and half of the doctors (51%) also revealed that in their opinion discriminative behaviours towards patients with obesity did occur.15 In this respect, the attitudes of Polish doctors and nurses are not significantly different from the tendencies observed in other countries. According to numerous reports, there is a rather common belief among medical staff that patients who have obesity ignore medical recommendations and do not take care of themselves.19–22 At the same time, health professionals quite frequently reveal that they do not feel sufficiently prepared for treating obesity.8,23

When comparing the declarative opinions and attitudes of the health care employees with the scale of discrimination experiences of patients who suffer from obesity, one can observe significant differences in the two groups’ narrations. Our research revealed that a significant proportion (82.6%) of Polish patients with obesity feel discriminated at health care facilities. In the perspectives of these experiences, we have received results which are more alarming than the ones published by Puhl and Brownell. In their studies, 69% of the respondents experienced being stigmatized by doctors, 46% by nurses and 37% by nutritionists.24 Above all, our respondents indicated doctors (90%) as the people who presented discriminative behaviours towards them. Nurses and midwives (51%), as well as nutritionists (14%), followed.

Many reports around the world revealed that obesity is a variable which correlates with medical staff’s negative attitudes towards patients.7,10,25,26 When it comes to medical staff’s improper behaviours, the patients that we have studied also mentioned a high rate of improper communication forms whose purpose was to modify their attitudes and behaviours concerning the illness. As many as 73% of them heard messages pointing to them being guilty while 89% experienced threats. Behaviours of this kind as well as their scale are really alarming. There are much data which show that improper narration towards patients who suffer from obesity deteriorates their adverse health situation and sense of being excluded. It also creates favourable conditions for their self-stigmatization. Fear, embarrassment and sense of guilt, which happens to be induced by health professionals (especially those who, due to their specialization, have an insight into the patient’s intimate sphere) results in the patients’ reluctance to seek medical help.5,6,27 It correlates with a lack of discipline in therapy and it is connected with deterioration of their condition.3,9,27 Therefore, it is important for health professionals to remain critical of their narration and avoid simplified messages which refer to responsibility for the disease.29 The attitude towards the patient should be focused on his or her future, support and building adequate therapeutic activities which concentrate on results connected with health and not the weight.29 Language has clinical significance (both therapeutic and iatrogenic); therefore, it is important that it is respectful and does not strip the patient of his or her dignity.30,31

Our research has revealed that nine out of ten patients believe that discrimination of people with obesity is a common occurrence in Poland. The largest number of respondents experienced unfair treatment due to their obesity in medical institutions, means of public transport, places where they go to rest or in their closest family. Eight out of ten respondents are of the opinion that patients with obesity are treated worse than patients with normal body weight by medical staff. This opinion is often shared by the participants who have experienced improper, unfair treatment in medical institutions. Apart from that, such incidents were reported more frequently by women, patients with chronic diseases, respondents with class III obesity and people who assessed their condition as bad or neither bad nor good. The negative experience of patients with obesity (even a one-time incident) seems to have a stronger correlation with the general assessment of medical staff’s discriminative behaviours compared to patients with normal weight. At the same time, we have not noticed any impact of positive experience on the general assessment of a relation. It seems to us that such a situation is connected with particular “discrimination sensitivity” of people with higher body weight who function in the perspective of pejorative social stereotypes in their everyday lives. Many scientific reports indicate that gender is a significant variable that correlates with the frequency of discriminatory experiences.11,32 Our research indirectly confirmed this relationship. We believe that women are more likely to experience discriminatory behaviour because they were over-represented in this study, but it is also possible that women tend to be more likely to be discriminated against than men. A similar conclusion can be drawn for people suffering from obesity who have higher education. In our study, people with higher education accounted for 57.5% of all respondents. This is an important variable because analogous reports indicate that people with secondary and higher education more often declare the experience of discrimination in contacts with health care than patients with lower education and healthy body weight.33

In this perspective, the limitations of our study should also be indicated. The results obtained through the adopted research technique are characterized by over-representation of women, young people, inhabitants of large cities and respondents with higher education. People who are characterized by these variables are among the most demanding patients. They expect relations with medical staff based on partnership and matter-of-fact messages of an informative character. On the other hand, they report the largest number of demands and negative comments concerning the behaviour of health professionals. In our opinion, the over-representations in the study may have affected the general level of the health professionals’ behaviours assessment in the analyzed categories. It should also be emphasized that we use the BMI index as the basic criteria for inclusion in the research. When constructing the research tool, we were aware of the imperfections of BMI, especially applied to the respondents’ self-condition. BMI does not take into account the muscle and bone mass and the age of the patients. The analysis of measurement data shows that for analogous declarative studies, the respondents overestimate their height and underestimate the weight. Ultimately, this results in an underestimation of body mass index by 1.1 points in men and 1.5 points in women.34 However, we considered BMI as a common criterion to be the best estimate of obesity and a commonly used predictor of disease.

The conclusions obtained by us prompted us to continue the topic and broaden the research perspective. We are currently conducting research among medical staff and medical students, the aim of which is to analyze the attitudes and experiences in dealing with obese patients in the field of knowledge related to obesity, the social situation of patients, and the ratio of relations between patients and medical staff. We assumed that the ultimate goal of our research would be to develop proposals for recommendations on the relationship with obese patients.

Conclusion

In our opinion, there is an urgent need for systemic support for health professionals when it comes to information on the methods and availability of obesity treatment in Poland. It also needs to be pointed out that there are no standardized regulations whatsoever concerning communication and handling of patients who struggle from diseases burdened with social stigmatization. In our opinion, there is a significant need to extend the research by analyzing the perspective of health professionals and students towards patients with obesity in Poland. It is our hope that thanks to obtaining the full picture of the patient stigmatization problem in medical facilities we will be able to develop a proposal for national guidelines which will effectively limit medical staff’s discriminative behaviours towards individuals with higher body weight.

Informed Consent and Ethical Approval

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The research was positively evaluated and approved by the Independent Bioethics Commission for Research at the Medical University of Gdansk (589/2017-2018).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the following institutions and associations for their help and support in conducting the research: the Ombudsman, the Commissioner for Patient’s Rights, the Polish Association for the Study on Obesity, Association of Bariatric Patients, as well as the media patron “poradnikzdrowie.pl”.

Disclosure

Dr Krzysztof Sobczak reports funds from OD-WAGA Foundation, during the conduct of the study. Dr Katarzyna Leoniuk reports funds from OD-WAGA Foundation, during the conduct of the study. The authors report no other potential conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. King EB, Shapiro JR, Hebl MR, et al. The stigma of obesity in customer service: a mechanism for remediation and bottom-line consequences of interpersonal discrimination. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91:579–593. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.579

2. O’Brien KS, Latner JD, Ebneter D, et al. Obesity discrimination: the role of physical appearance, personal ideology, and anti-fat prejudice. Int J Obes. 2013;37:455–460.

3. Sutin AR, Terracciano A. Perceived weight discrimination and obesity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70048. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070048

4. Obara-Golebiowska M, Przybylowicz E. Employment discrimination against obese women in Poland: a focus study involving patients of an obesity management clinic. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43:689–690.

5. Puhl R, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9:788–805. doi:10.1038/oby.2001.108

6. Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity. 2009;7:941–964. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.636

7. Huizinga MM, Cooper LA, Bleich SN, et al. Physician respect for patients with obesity. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1236–1239. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1104-8

8. Brown I, Stride C, Psarou A, et al. Management of obesity in primary care: nurses’ practices, beliefs and attitudes. J Adv Nurs. 2007;59:329–341. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04297.x

9. Tomiyama AJ, Carr D, Granberg EM, et al. How and why weight stigma drives the obesity ‘epidemic’ and harms health. BMC Med. 2018;16:123. doi:10.1186/s12916-018-1116-5

10. Hansson LM, Näslund E, Rasmussen F. Perceived discrimination among men and women with normal weight and obesity. A population-based study from Sweden. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38:587–596. doi:10.1177/1403494810372266

11. Hansson LM, Rasmussen F. Association between perceived health care stigmatization and BMI change. Obes Facts. 2014;7(3):211–220. doi:10.1159/000363557

12. Eurostat. Obesity rate by body mass index (BMI). Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/graph.do?tab=graph&plugin=1&pcode=sdg_02_10&language=en&toolbox=data.

13. Stepaniak U, Micek A, Waśkiewicz A, et al. Prevalence of general and abdominal obesity and overweight among adults in Poland. Results of the WOBASZ II study (2013-2014) and comparison with the WOBASZ study (2003-2005). Pol Arch Intern Med. 2016;126:662–671.

14. Obara-Gołębiowska M. Employment discrimination against obese women in obesity clinic’s patients perspective. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2016;67:147–153.

15. Sińska B, Turek M, Kucharska A. Are we dealing with stigmatization of obese patients in hospital wards? Assessment of medical staff attitudes. In: Kropiwiec K, Szala M, editors. Social Sciences and Humanities in the Face of Contemporary Challenges. Lublin: TYGIEL; 2015:42–52.

16. Sińska B, Kucharska A, Zegan M, et al. Nurses’ attitudes towards obese patients – a pilot study. Probl Hig Epidemio. 2014;91:161–164.

17. Sharpe D. Chi-square test is statistically significant: now what? Pract Assessment Res Eval. 2015;20:1–10.

18. Kwasiborski PJ, Sobol M. The chi-square independence test and its application in the clinical researches. Kardiochir Torakochir Pol. 2011;4:550–554.

19. Bocquier A, Verger P, Basdevant A, et al. Overweight and obesity: knowledge, attitudes, and practices of general practitioners in france. Obes Res. 2005;13(4):787–795. doi:10.1038/oby.2005.89

20. Hebl MR, Xu J. Weighing the care: physicians‘ reactions to the size of a patient. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(8):1246–1252. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801681

21. Brown I. Nurses’ attitudes towards adult patients who are obese: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(2):221–232. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03718.x

22. Budd GM, Mariotti M, Graff D, et al. Health care professionals’ attitudes about obesity: an integrative review. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24:127–137. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2009.05.001

23. Campbell K, Crawford D. Management of obesity: attitudes and practices of Australian dietitians. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:701–710.

24. Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Confronting and coping with weight stigma: an investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity. 2006:14:1802–1815.

25. Brown I, Thompson J. Primary care nurses’ attitudes, beliefs and own body size in relation to obesity management. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:535–543. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04450.x

26. Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, et al. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev. 2015;16:319–326. doi:10.1111/obr.12266

27. Spooner C, Jayasinghe UW, Faruqi N. Predictors of weight stigma experienced by middle-older aged, general-practice patients with obesity in disadvantaged areas of Australia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:640. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5556-9

28. Raves DM, Brewis A, Trainer S, et al. Bariatric surgery patients’ perceptions of weight-related stigma in healthcare settings impair post-surgery dietary adherence. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1497. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01497

29. Ramos Salas X. The ineffectiveness and unintended consequences of the public health war on obesity. Can J Public Health. 2015;106(2):e79–81. doi:10.17269/cjph.106.4757

30. Alberga AS, Russell-Mayhew S, von Ranson KM, et al. Future research in weight bias: what next? Obesity. 2016;24:1207–1209. doi:10.1002/oby.21480

31. Groven KS, Heggen K. Physiotherapists’ encounters with “obese” patients: exploring how embodied approaches gain significance. Physiother Theory Pract. 2017;1–13.

32. Puhl RM, Andreyeva T, Brownell KD. Perceptions of weight discrimination: prevalence and comparison to race and gender discrimination in America. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32:992–1000. doi:10.1038/ijo.2008.22

33. Carr D, Jaffe KJ, Friedman MA. Perceived interpersonal mistreatment among obese Americans: do race, class, and gender matter? Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:S60–68. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.453

34. Danubio ME, Miranda G, Vinciguerra MG, Vecchi E, Rufo F. Comparison of self-reported and measured height and weight: implications for obesity research among young adults. Econ Hum Biol. 2008;6:181–190. doi:10.1016/j.ehb.2007.04.002

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.