Back to Journals » Journal of Healthcare Leadership » Volume 10

Evaluation of a staff well-being program in a pediatric oncology, hematology, and palliative care services group

Authors Slater PJ , Edwards RM , Badat AA

Received 11 June 2018

Accepted for publication 11 September 2018

Published 15 November 2018 Volume 2018:10 Pages 67—85

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S176848

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Russell Taichman

Penelope J Slater,1 Rachel M Edwards,2 Ashraf A Badat1

1Oncology Services Group, Queensland Children’s Hospital, Brisbane, QLD, Australia; 2Nursing Learning and Workforce Development, Queensland Children’s Hospital, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Purpose: Challenges experienced by staff in the Oncology Services Group at Queensland Children’s Hospital led to issues with staff retention, well-being, and stress on team culture. Therefore, a customized program was developed through a needs analysis to improve the well-being and resilience of oncology staff, enabling them to cope with stressors and critical incidents inherent in their everyday work and to flourish. The program included education, on-site counselors, mindfulness sessions, debriefing, well-being resources, and improved engagement, support, and communication.

Methods: Evaluation of the program in the first year examined program participation, staff feedback following education workshops and mindfulness sessions, staff retention rates, and the results of an annual organizational staff survey and a program outcome survey.

Results: Approximately 76% of staff attended the Introduction to Well-being workshop, and 98% of responses to survey questions were positive. Staff also provided positive feedback on the other well-being workshops and sessions embedded within existing education programs. Employee Assistance Program counseling sessions had an 81% uptake, with a wide variety of presenting issues, 62% related to work. All participants in mindfulness sessions agreed that it was a valuable tool to improve clinical practice, 94% said it had an immediate positive impact on their well-being, and 70% agreed that they were applying mindfulness principles outside the sessions. Staff retention and turnover improved. Staff reported a positive effect on awareness of self-care, addressing risks to resilience, seeking support from trusted colleagues, coping with critical incidents, and the ability to interact positively with patients and families.

Conclusion: The evaluation showed a positive impact on staff well-being. Although there was a wide variety of successful interventions reported in the literature, sustainability needs to be considered. Feedback on this program found that staff appreciated being listened to, valued, and supported through the strategies, and the ongoing program will continue to monitor staff needs and be responsive in building their resilience and well-being.

Keywords: staff well-being, resilience, burnout, vicarious trauma, self-care

Introduction

It is well documented that there is a high risk of burnout in the health care environment, which can have serious consequences for both the staff and the people for whom they care.1–18 Burnout has been reported by 31% of cancer workers in Queensland.16 A survey by the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia revealed that 33% of members with direct patient contact and 27% with no direct patient contact had high levels of emotional exhaustion.18 Those that work in pediatric oncology had heightened risks based on the long-term nature of relationships with children and their families through cancer treatment.19,20

Burnout is a complex physiological and psychological experience or response of an individual to stress as it relates to their workplace. Unlike acute stress, such as that following trauma, burnout occurs in response to prolonged exposure to stress.21,22 The literature describes measurable consequences of burnout, including emotional exhaustion, negative views, reduced personal accomplishment, and depersonalization.23,24

In response to the high risk of burnout, the US Institute for Healthcare Improvement recommended that organizations take a systems approach to building well-being and resilience, commencing with identifying what matters to staff and the factors that reduce their joy at work.25 The implementation of a range of strategies that target specific staff needs is required to encourage mental and emotional stability and build resilience.6

Reviews of resilience theory and interventions show a variety of proposed definitions, which center on the two core concepts of adversity and positive adaptation.26–28 Definitions include the ability to adapt positively, remain functionally stable and well, or bounce back in the face of adverse life circumstances, trauma, tragedy, threats, or significant sources of stress.27 Resilience can be viewed as an outcome or state following adversity or as a process of adjusting to adversity through resilience.26 To improve clarity, it has been suggested that the term “resilience” is used for the process, and “resilient” for the outcome.26 Resilience can be developed through training, including mindfulness and/or cognitive and behavioral skills, which should be considered part of the career development of those at risk, such as the health care workforce.27

Well-being programs that build resilience reported in the literature have delivered multidimensional interventions with a variety of components. Relevant training was a common factor in these programs.7,20.29–31 Oncology workers in Queensland had a high level of interest in attending workshops and were motivated to acquire knowledge and skills to prevent or address burnout.5 One such example of education for pediatric nurses in the US included a mix of teaching, case presentations, and practical tools.32 It is recommended that training on coping and resilience should be delivered as early as possible to prepare nurses for placements and employment in pediatric oncology.19

In addition to training, staff need a range of personnel- and organization-directed interventions to address the risk of burnout,33 including job-related resources (such as positive feedback and social programs) and personal resources (eg, self-evaluation of strengths and web-based education).34 The Sati Center recommended strategies along organizational, interpersonal, educational, lifestyle, and personal domains.29 A review of coping and resilience in pediatric oncology nurses9 found strategies needed to be flexible, diverse, and acknowledge the personal nature of coping and resilience.19

Despite the risk of burnout, there are many rewards from working in health care.4,17,35–37 Health practitioners can undergo a transformation with experience, as they reflect, become more self-aware, and learn to sustain themselves through robust coping mechanisms and self-care strategies.38

An example of an effective strategy is the use of mindfulness as a stress-management tool in health care organizations.39 It has its roots in the tradition of Buddhism, and has been integrated recently into several treatment approaches, including dialectical behavior therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.40 Mindfulness cultivates moment-to-moment present awareness, with an attitude of nonjudgment, acceptance, and openness.40 Mindfulness cultivates an ability to stand back from our thoughts, feelings, and sensations. It is an extension of the concept of reflective practice.41 Epstein advocated that mindfulness be considered a characteristic of good clinical practice, as a link between relationship-centered care and evidence-based medicine.42 According to Epstein: “The goals of mindful practice are to become more aware of one’s own mental processes, listen more attentively, become flexible, and recognize bias and judgments, and thereby act with principles and compassion”.42

This paper reports on the evaluation of various strategies implemented in the Oncology Staff Well-being Program in the Oncology Services Group at Queensland Children’s Hospital within Children’s Health Queensland (CHQ) Hospital and Health Service. Following the move from the Royal Children’s Hospital to Queensland Children’s Hospital in late 2014, there were challenges with settling into the new facility, team workload, public scrutiny and consumer expectations. Concurrently, there was an increasing number of high-acuity and complex patients. This resulted in issues with staff resilience and retention that impacted the team during 2015 and 2016. To determine the best way to support staff, a needs analysis43 was conducted with the staff of the Oncology Services Group, supported by the director of the service and with advice from CHQ People and Culture, the Employee Assistance Program (EAP), and an external psychologist.

Following this, a program was developed with the goal of improving the well-being and resilience of oncology staff, enabling them to cope with the inherent work stressors and to flourish. The well-being program was implemented in two parts, with the initial phase addressing urgent individual needs and the next focusing on team culture. A range of well-being strategies were delivered, including embedding well-being training sessions within the existing education programs, a review of the debriefing process, EAP counselors on site, mindfulness sessions in clinical areas, targeted workshops with multidisciplinary teams, group supervision, developing and following up on self-care plans, provision of information and resources on well-being, including a Facebook page, and tools for staff to assess their character strengths, self-care, and well-being. Other strategies included improving staff awareness of family milestones, (such as end of treatment), mentoring of quality activities, acknowledging staff achievements, initiating a well-being “champions network”, addressing equipment and facility issues, connecting staff through social activities, and communicating self-care opportunities. These strategies were evaluated to obtain ongoing feedback and ensure staff involvement in the program’s evolution, and to be certain it was continuing to meet their needs. This paper reports on the evaluation in the first year and the direction of the program.

Methods

Process and impact evaluation of the well-being program strategies were guided by a program logic with a hierarchy of outputs and short- and long-term outcomes of the program. The program logic informed the development of the questions included in the surveys, evaluating different strategies and the program as a whole. The overall goal of the program was to improve the well-being and resilience of oncology staff, enabling them to cope with the stressors and critical incidents inherent in their everyday work, and to flourish. The strategies implemented and their evaluation included:

- education workshops – process evaluation through participant statistics, impact evaluation through surveys taken of participants immediately following the session

- EAP on site counseling – process evaluation through records of participants and the topics covered

- mindfulness sessions – process evaluation through records of participants, impact evaluation through surveys conducted in the first 6 months

- Facebook page – process evaluation through records of participants and likes

Outcome evaluation was undertaken via an Oncology Staff Well-being Outcomes Survey, oncology staff responses to the Queensland Government Working for Queensland Survey, and staff metrics.

The samples involved in the different evaluation strategies were all taken from staff of the Oncology Services Group and were dependent upon their recruitment to that strategy. Participants in the education program were supported by their line manager and rostered for the session. EAP on site counseling was either supported by the manager or attended in staff members’ own time, as preferred by the attendee. Any staff member could attend mindfulness sessions and be invited to the Facebook page. The number of surveys completed and/or attendances for the different strategies are shown in Table 1. Analysis was undertaken by the coordinator of the program using descriptive statistics and thematic analysis of comments, and was overseen by the Oncology Staff Well-being Working Group.

Education program

The well-being education program included targeted workshops and individual sessions embedded within the existing Oncology Services Group Education Program. The program encompassed several teaching strategies and styles, including didactic lecture, interactive questioning, reflection, case discussion, and role play. Theoretical content was delivered in a didactic and/or written form (handout). Some training was performed in an interactive style with visual aids for reflection, small-group discussion, workbooks, and self-assessment tools. The theory was designed to build the recipients’ knowledge and skills over the education program, from novice to expert, and was responsive to the experience of the participant, where more advanced concepts and skills were explored progressively in other workshops.

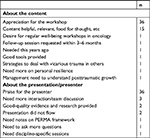

A series of three well-being workshops were conducted by an external senior psychologist and evaluated with a one-page survey completed by participants. The surveys were provided to all participants at the end of each well-being workshop, and included questions on relevance, value, and the process of the sessions and gave opportunity for comments on what main tips they had gained and suggestions they had on improving staff well-being (Figure S1).

Workshops to the end of 2017 were:

- Coping with Critical Incidents. These were run as 1-hour small-group interactive sessions. Eight separate workshops were run over a 2-day period in November 2016, with a total of 54 attendees (85% nursing, 4% administration, 11% allied health).

- Introduction to Staff Well-being. Subtitled “Managing Vicarious Trauma and Sustaining Resilience”, these 3-hour didactic workshops were conducted with larger groups. Three were conducted in November 2016, then repeated in February, April, July, and October 2017. In addition, a condensed workshop was offered as two 1-hour sessions for medical staff in May 2017, to assist with engagement. There were 132 attendees in the eight workshops held at Queensland Children’s Hospital (58% nursing, 27% allied health, 8% medical, 8% administration). In addition, nine staff (one medical, four nursing, four allied health) from the regional state-wide shared-care units participated in one of the sessions via videoconference, and others received a recording. Of the total staff associated with the Oncology Services Group, 76% attended an Introduction to Staff Well-being workshops up until October 2017. This included 10 of 25 medical staff (40%), 76 of 101 nurses (75%), 11 of 16 administration staff (69%), and 100% of the 35 allied health staff (including research and quality staff).

- Resilience. This 2-hour didactic workshop was conducted with large groups and was designed to be an extension of the resilience content from the Introduction Workshop. Run in September and November 2017, the two workshops had a total of 32 participants (19% administration, 44% nursing, 3% medical, and 34% allied health).

- In addition, sessions related to well-being were included in the service’s existing staff education program. Surveys provided at the end of the workshop asked participants to rate the value of those sessions (extremely valuable, valuable, neutral, minimal value, no value). Well-being sessions were included in the following:

- Fundamentals of Pediatric Oncology Program – a 2-day workshop scheduled four times per year, including 1-hour sessions entitled “Understanding Grief and Loss” and “Looking after You”; the four fundamental workshops in 2017 had 78 attendees in total

- Advanced Pediatric Oncology Program – a 1-day workshop scheduled five times during 2017, including one-hour sessions entitled “Validation Skills Training”, “The Impact of Death on the Team”, and “Oncology Staff Well-being Program”; 45 staff attended these workshops

Six of the weekly 1-hour Thursday oncology education meetings in 2017 were dedicated to staff well-being with the topics of “Oncology Staff Well-being Program”, “Managing Grief and Loss as a Health Worker”, “QSuper Superannuation”, “Practical Application of Self-Care Strategies by Exercise, Mindfulness, and Music Therapy”, “The Resilient Clinician”, and “Valuing Mental Health Forum”. Attendance records for these six sessions showed an average of 24 attendees, with a range of 14–32.

Employee Assistance Program on site

The Oncology Services Group piloted an EAP on-site counseling service for CHQ, with an experienced counselor being available on the campus (in a separate building to the hospital) 1 day a week on alternating days. During the day, six 50-minute sessions were available for staff to book. Bookings could be made directly through a limited-access Outlook calendar for which there were two administrators or by contacting the administrators directly. Group sessions were also available for staff to discuss issues that arose. Records were maintained of staff numbers attending. EAP on site counseling was offered on 32 days in total, from the beginning of February to the end of September 2017. The counselor collected figures on sessions and their general content based on categories used by the service provider to report back to CHQ. No individual evaluation was undertaken of these sessions to protect staff privacy, but general unidentifiable feedback from staff was collected in the outcome survey.

Mindfulness

Short (10–15 minutes) mindfulness sessions were conducted twice per week by the service’s psychologist in each clinical area (Oncology Inpatient Unit and Oncology Day Unit). Attendance sheets were kept for each session. For 15 sessions (as convenient) between December 2016 and May 2017, consenting participants were provided with a one-page survey at the end of the session to evaluate its impact (Figure S2). Staff were also asked how often they would like mindfulness sessions and any other comments or suggestions. There were 592 attendances at 88 mindfulness sessions provided in the year from November 2016: 26 sessions held in the Oncology Inpatient Unit and 62 in the Oncology Day Unit. Attendees comprised 3.4% medical, 78.8% nursing, 4.4% allied health, and 13% administration staff.

Facebook page

This online forum was created with security settings to ensure it was available only by invitation from existing members and with posts requiring approval by one of the two group administrators. It was established as a “secret” group, with 90 staff initially invited on December 22, 2016. The membership has since stabilized at 82 members, with new staff being invited as they were recruited to the oncology team. The page was used to share posts on well-being, circulate resources, and advertise events, such as workshops and external professional development opportunities. It was evaluated as part of the outcome survey.

Working for Queensland Survey

The annual Working for Queensland Survey was conducted by the Queensland government to measure Queensland public-sector employee perceptions of their work, manager, team, and organization.44 The survey explored the workplace climate through 48 questions under the categories of employee engagement, job satisfaction, and leadership in the public sector. It also collected information on the workplace, employment history, demographics and role of the respondent.

Access to raw data was restricted, and reports were provided by the Queensland government in such a way as to protect the confidentiality of the participants. Most data were expressed as percentage positive, percentage neutral, or percentage negative, where:

- percentage positive represented the proportion of respondents who expressed a positive opinion or assessment, ie, combining “strongly agree” and “agree” responses

- percentage neutral represented the proportion of respondents who expressed a neutral opinion or assessment

- percentage negative represented the proportion of respondents who expressed a negative opinion or assessment, ie, combining “strongly disagree” and “disagree” responses.

The percentage-change figure and division comparisons were highlighted in the report when the 2017 work-area result was five or more percentage points higher or lower than the 2016 score.

The survey was conducted in May 2016 (6 months before the well-being program was implemented) and August 2017 (10 months after implementation commenced). The results were broken down for Oncology Nursing and the whole of the Oncology Services Group and compared to the higher levels of the organization: the Division of Medicine and the Hospital and Health Service (CHQ).

Staff metrics

The business-planning framework for nursing in each clinical area had an established number of full-time-equivalent staff. As there was active recruitment during the course of the study, new-starter numbers reflect openings within the area from retirement, secondment, transfer, or resignation. As such. the number of new nurses in the service that were provided a service orientation in the years prior to and during the first year of the well-being program was used as a proxy measure of staff retention. Official staff-turnover rates did not include movements out of the oncology area or Queensland Children’s Hospital (only those out of Queensland Health), so staff turnover was calculated from manual records kept by the Nurse Unit Manager of the Inpatient Unit for each financial year. The sick-leave rate was investigated, although this is not considered a good measure to use in oncology areas, as people are advised to utilize sick leave when unwell to avoid transfer of infection to immunocompromised patients.

Oncology Staff Well-being Program Outcomes Survey

This survey (Figure S3) gave an avenue for staff to provide feedback on the overall well-being program, including Likert scales on the value of the individual strategies and the benefit provided to them or their team. The respondents were able to provide suggestions regarding the well-being initiatives, whether they were interested in being a “well-being champion” or mindfulness facilitator, and any new initiatives they would like to see, with any other comments. The survey was distributed electronically through Survey Monkey to all staff, in addition to paper copies available in clinical areas, in September 2017 for a period of 6 weeks. The Oncology Staff Well-being Outcomes Survey was completed by 44 people: one medical, 31 nursing, nine allied health, and three administration staff. Five staff were from the Oncology Day Unit, 17 from the Oncology Inpatient Unit and sister wards, eleven from the clinical directorate area, including clinical nurse consultants and staff of specialized services, and nine from allied-health staff caring for oncology patients.

Ethics

A waiver of ethics review was granted by the CHQ Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee for this quality-assurance activity, which was conducted within all best-practice ethical guidelines. The study was conducted in full conformance with principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, good clinical practice, and within the laws and regulations of Australia. The staff interviews for the needs analysis were covered by ethics approval HREC/10/QHC/51 – “Discovery interviews: consumer, carer, and clinician perceptions and experiences of Queensland Health services” – and all staff signed the participant-information and -consent form. All participants were Queensland Children’s Hospital staff working with patients of the Oncology Services Group and participated in the program voluntarily. The Working for Queensland Survey was a whole-of-government survey, managed through a central agency. The well-being program was low-negligible risk to participants, as there was no foreseeable risk of harm or discomfort, apart from alerting participants to their self-care practices and behavior that may negatively impact their own well-being. All sessions were supported by psychologists, and an EAP on-site counseling service was provided to all participants. The Working for Queensland Survey was anonymous, the education workshop and mindfulness surveys included optional names, and the outcome survey had a section for the respondent’s name. Data confidentiality and participant privacy were protected through appropriate locked storage of original survey forms and password-protected electronic storage of information. Reports and papers included only grouped and de-identified information. Individuals benefited from participation in this program by improvements in their well-being through education, implementation of identified self-care strategies, access to EAP on-site counseling, mindfulness sessions, staff debriefing, and improved connections with their team.

Results

Education program

Coping with Critical Incidents workshops

Evaluation surveys were completed by 52 staff (96% response rate), and for all questions taken together >92% of staff responses were positive (agree or strongly agree; Table 2). In survey comments, staff particularly valued the information on self-care strategies (26) and emotionally disengaging or dialing up and dialing down empathy (seven). They requested more and regular workshops (five), debriefing (four), and team-building activities (one).

Introduction to Staff Well-being workshops

There were 127 surveys completed (96% response rate), and for all questions taken together, >98% of responses were positive (agree or strongly agree; Table 2). Staff that commented on the main tips they gained from this workshop particularly mentioned planning and implementing self-care, awareness of vicarious trauma, coping with stress, understanding PERMA (positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, achievement), knowing their triggers, and practicing mindfulness (Table 3), eg:

Understanding that we are all exposed to vicarious trauma and realizing I do need to develop ways to improve my resilience: have to, not should

Recognize when I need to step away, be more confident to address when I need to look after myself

Resilience workshops

A total of 28 surveys were completed (88% response rate), and for all questions taken together >93% of the responses were positive (agree or strongly agree; Table 2). The main tips that staff gained from these workshops were using techniques to improve resilience, such as breathing practices, mindfulness, implementing self-care, using transitions or the third space, improving self talk, and being self-aware and reflective (Table 3).

General comments provided by staff in the introduction and resilience workshop surveys are shown in Table 4. Staff appreciated the workshops, found the content helpful, and praised the presenter, eg:

I appreciate that Oncology Services has recognized/invested in staff well-being. Thanks!

Fantastic. How often do we forget about ourselves when caring for our patients? Thank you for this reminder/refresher.

As part of our ongoing monitoring of staff needs, staff were also asked in the surveys to suggest ways to improve well-being (Table 5). Suggestions included additional or regular workshops, debriefing, regular self-care activities, good role modeling by the management, and team building/reflection.

| Table 5 Suggestions for the well-being program provided in the surveys following the workshops and in the Oncology Staff Well-being Outcomes Survey |

Fundamental and Advanced Pediatric Oncology workshop evaluation

Over the four Fundamental workshops, an average of 92% found the session on grief and loss valuable or extremely valuable (49 survey responses) and 94% for the “Looking after you” session (47 responses). In the five Advanced workshops in 2017, 100% of participants found the “Validation skills” session valuable or extremely valuable (38 responses), 82% for the well-being program information (35 responses), and 92% for the “Impact of death” session (34 responses).

Oncology Thursday education meetings

These sessions were not individually evaluated, but staff feedback was positive and also served to continue to raise awareness of the program.

Employee Assistance Program on site counseling

Of the 192 offered sessions over the 8 months, 139 were booked (72% uptake). The afternoon appointments were offered to Emergency and Pediatric Intensive Care Unit staff over the last 6 weeks, and only three of these appointments were used. Prior to this, Oncology Services uptake was 81%. Attendees came from all areas of oncology: 76% nursing, 12% administration, 7% allied health, and 1% medical. In addition, 4% of sessions were devoted to exploring the management of the program.

The presenting issues recorded in the 139 sessions were related to career (13), burnout/stress/overwork (18), nature of the work (16), work–life balance (eight), conflict, bullying, or team dynamics (31), mental health (22), family issues (19), and personal issues (12). One staff member commented on the outcome survey:

Having the availability of one-on-one sessions to staff . . . has been invaluable: good coping strategies and self-care, debrief, and excellent to know that the organization cares. Very important; they need to continue.

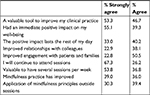

Mindfulness sessions

Evaluation forms were completed by 107 participants between December 2016 and May 2017 (79% nursing, 15% administration, 6% allied health, 1% medical, and 6% unknown; Table 6). In summary, 100% of participants agreed that mindfulness was a valuable tool to improve clinical practice, 94% said it had an immediate positive impact on their well-being, and 70% agreed that they are applying mindfulness principles outside the sessions. Comments by staff in the surveys included:

The session was really great to insert some calm into a busy shift.

Good to stop and breathe.

Relaxing, putting thoughts in perspective.

| Table 6 Evaluation of the mindfulness sessions (n=107) Notes: Other response options were “neither agree or disagree”, “disagree”, and “strongly disagree”; n, total surveys completed. |

Facebook page: Oncology Staff Well-being Group

Between January and November 2017, there was an average of 12 posts per month, seen by an average of 45 staff, and liked an average of 31 times.

Outcome evaluation

Below are some comments that staff contributed voluntarily during the program through email or in interviews in other research:

I have been aware in recent weeks of a steadily returning level of stress and distress that I can now no longer manage. I have utilized the Oncology Well-being Program today so I could professionally check myself and gauge the level of distress that I am feeling. Thank you for this wonderful program – I feel valued as a member of staff.

I felt the well-being program approach was excellent: grounded in a strong evidence base, multipronged, gentle, acknowledging the multilayers (individual, team, organization). Everyone should be involved in and take responsibility for individual and team well-being.

The new well-being program was . . . encouraging employees to talk about how they feel. Employees stated that it was less about the content of well-being sessions and more about being appreciated, that the organization was looking after the staff.

Working for Queensland surveys

Table 7 shows results related to staff well-being from the 2016 and 2017 Working for Queensland surveys provided by the Queensland government. The reports highlight areas that were at least 5% greater or 5% less than the comparison. The work–life balance questions had improved between the two surveys, and were also favorable compared to the Division of Medicine and CHQ. Positive responses to “being overloaded with work” and “work having a negative impact on health” declined in the year, and this was in line with the Division of Medicine and CHQ results. Interestingly, “respect within workgroups” declined markedly between the two surveys, although being “able to receive help and support from the workgroup” improved. Oncology had good results for “managers supporting well-being” for nursing compared to CHQ, and “intention to stay in the organization”. Generally, medical staff, male staff, and older staff, as well as those who had been in the agency 2–5 years, showed less positive responses.

Reports of witnessing bullying increased from 2016 to 2017. In 2017, 51% of oncology staff had witnessed bullying or sexual harassment in the past 12 months (30 of 59 respondents), and 31% of respondents had been subjected to bullying in oncology: 72% by a fellow worker, 28% by an immediate manager, 22% by a client/customer, and 17% by a group of fellow workers. The type of bullying was 78% verbal abuse, 33% inappropriate and unfair application of work policies and rules, 22% other, and 11% physical behavior (assault or aggressive body language). In contrast, bullying in CHQ was 49% fellow workers and 63% verbal abuse. For Oncology Nursing in 2017, 33% reported being subjected to bullying.

Staff metrics

The introduction of the Oncology Staff Well-being Program in November 2016 brought about a marked improvement in the retention of staff as demonstrated in the number of new nurses required to fill positions. There were 36 new nurses in 2015 and 27 in 2016. In 2017, there were only 13 new starters, indicating improved nursing-staff retention. The turnover rate, which included resignations, movements to other districts in Queensland Health, and other areas of the Queensland Children’s Hospital, was 28.5% for 2014–2015 (following the move to Queensland Children’s Hospital at the end of November 2014), 42.5% for 2015–2016, 14.8% for 2016–2017, and 19.2% for 2017–2018. Note that the needs analysis commenced in August 2016 and the program commenced in November 2016. As expected, the sick-leave rate was higher for oncology than other areas of the hospital. The whole of the Division of Medicine had a sick-leave rate of 5.2% over the 3 years compared to 6.7% in the Oncology Inpatient Unit.

Oncology Staff Well-being Program Outcome survey

The strategy that the largest percentage of staff found “extremely valuable” was EAP on site counseling (81%), followed by debriefing and education through well-being workshops and Advanced Oncology Program sessions (Figure 1). All staff who accessed mindfulness sessions and debriefing rated them as “valuable” or “extremely valuable”. All the education sessions rated highly. The well-being resources and the Oncology Staff Well-being Facebook page were less highly regarded, but still had 80% and 67% of staff, respectively, rating them as “valuable” or “extremely valuable”.

| Figure 1 Results from the Oncology Staff Well-being Outcomes survey related to evaluation of well-being strategies. Abbreviation: EAP, Employee Assistance Program. |

Staff reported that the well-being program facilitated many improvements in awareness and behavior (Table 8). It particularly made a positive difference in overall well-being and raised awareness of the importance of self-care, developing a self-care plan, and addressing risks to resilience and well-being. It also brought to staff’s attention the importance of connecting with trusted colleagues.

The survey showed that the well-being program was least useful in prompting discussions with managers about well-being, increasing engagement at work, and seeking out opportunities to see positive outcomes from their work. Six respondents said they would be interested in becoming a well-being champion or mindfulness facilitator.

Three questions at the end of the outcome survey asked for any suggestions regarding the current well-being program, any new initiatives they would like to see, and any other comments (Table 5). Fourteen comments were about making the workshops more accessible through rostering and backfill and having workshops at different times of the day. Nine comments encouraged the continuation of the program, with multiple options and regular offerings, seven wanted increased EAP on-site counseling sessions, six were grateful for the acknowledgment of the strain of the caseload, and five were supportive regarding mindfulness, eg:

The program has improved the overall culture of support, including counseling allowing this often-taboo subject, to have a voice . . . it has also increased manager awareness of well-being and the impacts felt by staff working in this service.

Thank you for acknowledging the strain the oncology caseload can put on staff well-being.

It is so wonderful to have this initiative being driven and supported by the oncology leadership team. It truly makes me feel valued and supported in this workplace.

Cost–benefit analysis

The financial benefits of the program were estimated in terms of reduced recruitment costs for ten staff, new staff orientation and training, and cost of leave for two staff associated with burnout and stress. This exceeded the direct costs of external services provided by 25% and also the total costs when the in-kind services and support provided by staff were added. The nonfinancial benefits further added to the advantages of the program, including improved staff well-being, team morale, and engagement in patient safety strategies.

Sharing our findings

Information was shared with internal stakeholders via newsletters, posters, emails, meetings, patient safety rounds, workshops, working groups and the Oncology Staff Well-being Facebook page. CHQ management commenced development of a whole-of-CHQ well-being and resilience program during 2017, and one member of the Oncology Services Group Staff Well-being Working Group was a member of the CHQ working group. Findings from oncology were applied to the wider health service, and the EAP on-site strategy was used as a pilot for CHQ.

The findings of the program have been shared through publications and conferences, such as the Australian and New Zealand Children’s Hematology/Oncology Group Annual Scientific Meetings in 2017 and 2018 and the Cancer Nurses Society of Australia Congress in 2018. Promotion of the program also occurred through the Queensland Safe Work and Return to Work Awards 2017, in which the program was a finalist, and in the Queensland Health Awards for Excellence 2017, in which it was highly commended.

Discussion

The literature reports the success of various strategies to promote well-being. In oncology settings, support from peers and managers has been found to be protective, along with multilevel strategies to improve the balance between the effort and reward involved in the work.7 A review on stress in pediatric oncology nurses found a wide range of stress-prevention and management interventions and proactive strategies had improved the mental health of staff.20 Research with nurses working in a pediatric bone-marrow-transplant unit in the US advocated for education, stress management, self-care and resilience building, improved interdisciplinary communication, and accountability and positivity in the team.31 Social support from peers, self-care strategies, such as exercise, and methods of relaxation to reduce stress were found to be moderating factors for burnout in a cancer center in New York.1 A multidisciplinary team in an English children’s hospice emphasized the importance of regular, structured, and dedicated clinical reflection time that also encouraged support and learning, discussed work-related stress, and provided awareness of signs of burnout.45 Specific interventions reported to be successful in the literature include peer-supported storytelling,46 self-care/wellness retreats,47–49 promotion of acceptance,50 relaxation techniques and art,51 and mindfulness meditation.52–54

Research suggests that mindfulness training for health-care professionals can function as a viable tool for promoting self-care and well-being.55 Mindfulness practice has been correlated with improvements in primary-care physician levels of burnout, mood disturbance, and empathy,56 suggesting that enhancing clinicians’ attention to their own experience increases their attentiveness toward their patients and reduces their distress.41 A review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals showed lower levels of perceived stress, decreased ruminative thoughts, and increased ratings of self-compassion.55 In addition, mindfulness practice can enable clinicians to communicate more effectively, listen to their patients with greater attention, help them recognize bias and judgment in their own thinking, increase their awareness of their own mental processes, and improve the quality of their therapeutic relationship with patients.54 Mindfulness practices can also enhance patient safety by increasing clinicians’ attentiveness and enhancing their ability to identify concerns (including their own thoughts and feelings) that may lead to diagnostic and medication errors.57 The experience of staff who accessed mindfulness sessions in this study supported these described benefits, and participants unanimously agreed that mindfulness improved their clinical practice. They described feeling immediate positive effects, particularly on their own well-being, and many of them were able to apply mindfulness practice outside the sessions.

The various strategies implemented in response to staff needs in the Oncology Staff Well-being Program were met with overwhelming satisfaction from participants. The program was developed at a time of great need, where managers were working tirelessly to stabilize the workforce and support existing staff during an especially distressing and clinically demanding time in the service. This emergent need drove managerial support for the program and fueled efforts to encourage staff to attend and utilize the individual strategies.

These efforts at implementation were extraordinary, with education staff providing backfill in the clinical area, staff being offered to come in (paid) on days off, changes to rostering practices, and innovative scheduling used to support attendance and minimize resource expenditure when accessing external providers. Staff well-being is now integrated into business as usual for the service, including routine mindfulness and debriefing sessions. Well-being has also been embedded into different levels of staff learning and development, from induction into the service to advanced practitioners, through the Oncology Education Program, patient safety rounds, and leadership meetings.

Administration, allied health, and nursing staff specifically were rostered to attend. Medical staff had to fit the workshops around their work, and thus were less likely to attend, although we did see engagement from junior medical staff in the mindfulness sessions. During implementation, it was observed that medical staff participation and attendance was more likely when the education program was targeted specifically to their own discipline or when medical presenters were utilized.

As with any new program, several issues were faced during the development and implementation of the program. These were discussed with members of the working group and decisions progressed. For example, the concept of well-being champions was met with some trepidation, as managers were reluctant to increase the burden of staff willing to take on this role where there was perceived risk of further exposure to distress. There could also be more systematic follow up of self care plans by individual managers in performance coaching and development sessions. The evaluation of the program could be improved through exit interviews with staff leaving the service and repeated interviews with staff periodically to identify any new or remaining unmet needs. The well-being program was implemented in two parts, with the initial phase addressing urgent individual staff well-being needs and the next phase focusing on team culture. Unfortunately, circumstances related to the implementation of a patient-information system upgrade delayed the second phase of the program until late 2018. While the leaders of the service have been actively supportive and integral to the success of the program, their support will need to be sustained to have ongoing success with the integration of this program in the service being business as usual.

Even with the implementation of a wide variety of interventions, the long-term impact of well-being programs has been questioned. A review of palliative care staff well-being strategies described education, relaxation, support, and cognitive training interventions, but could find no support that these were improving the well-being of staff.30 Others have concluded that stress-management interventions needed to be offered over the long term, with refresher sessions to ensure sustained impact.33,58

It was important that this program was preceded by a needs analysis with the staff. Consulting staff and addressing their specific needs is an identified way of ensuring positive well-being outcomes from programs such as this. Collaborative approaches to well-being programs empower staff to be involved in their design and implementation so they are tailored to the needs of the team.10 The success of a US-based wellness program was attributed to staff involvement in developing the program,32 and a review related to pediatric oncology nurses emphasized the importance of knowing how nurses cope to develop targeted strategies to enhance this ability.19

The establishment of a well-being program does not negate the responsibility of staff to undertake individual strategies to enhance their own well-being. However, programs structured to their needs will facilitate the natural personal transformation that takes place as health care workers mature into their role and will prevent them from being derailed through burnout. This transformation takes place as staff understand that their work has an emotional burden and that they need a plan for self-care, develop the ability to recognize their limitations, and have balance between their personal lives and the cost and satisfaction of caring.38

This program provided content that staff acknowledged in the evaluation had improved their understanding of the key concepts of well-being. Staff also expressed that the existence of the program made them feel valued and supported. Maya Angelou is often quoted as saying: “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” A crucial aspect of the Oncology Staff Well-being Program was that the leaders demonstrated in their actions that staff were a valued and precious resource, their needs were listened to and addressed, and they were supported through education and well-being strategies, resources, and tools. Embedding practices of staff appreciation and support into daily behavior is essential to translate the findings authentically from the program into practice.

Conclusion

Although there was a wide variety of successful interventions implemented in the first year of this program, sustainability needs to be considered in the future. The examination of individual uptake of well-being strategies, such as self-care planning, will provide useful information about the integration of teaching into practice. Future implementation will go beyond addressing the needs of individual staff and start addressing the organizational aspects of well-being, such as team culture, that were highlighted in the needs analysis and the Working for Queensland Survey. This will be done by revisiting standards of behavior in the Oncology Team Charter of Behavior, developing accountability systems for poor behavior, an antibullying campaign, and improving communication through training in crucial conversations.59 There will be ongoing well-being workshops, integrated social activities, designation of well-being champions and mindfulness facilitators, and improved team learning from incidents and near misses. Initiatives with regard to peer-supervision models will continue to be explored within the whole CHQ Well-being and Resilience Strategy. Mindfulness practice will be made more accessible through short 5- to 10-minute meditation sessions with noise-reduction headphones in each staff area, along with audio and written mindfulness resources. Staff needs will continue to be monitored, and the program will be dynamic in response to those needs. As we continue to address staff needs and reinforce the importance of self-care, resilience, and support as part of everyday work, the program will facilitate the transformation of staff to resilient workers who can sustain themselves through challenges.38

Acknowledgments

Gratitude goes to the support provided by the other members of the Oncology Staff Well-being Working Group and staff that provided services for the program, including Dr Wayne Nicholls, Cathy Sullivan, Cathy Henry, Majella Leahy, Amanda Carter, Maggie James, Dr Leigh Donovan, Sarah Baggio, Angela Delaney, Mick O’Keeffe, Susan Blair, and the staff specialists who supported debriefing. Thanks also to Claire Morley, Angela Saric, Michael Aust, and Lana Conic of the People and Culture team, the CHQ Well-being and Resilience Working Group, Liz Crowe, and our external providers; Marion Bell from Optum, and Tere Vaka and Penny Gordon from Penny Gordon and Associates. Support for this program has been provided through the Oncology Services Group and the Safety and Well-being area of People and Culture, Children’s Health Queensland.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Kash KM, Holland JC, Breitbart W, et al. Stress and burnout in oncology. Oncology. 2000;14(11):1621–1637. | ||

Sabo BM. Compassion fatigue and nursing work: can we accurately capture the consequences of caring work? Int J Nurs Pract. 2006;12(3):136–142. | ||

Sherman AC, Edwards D, Simonton S, Mehta P. Caregiver stress and burnout in an oncology unit. Palliat Support Care. 2006;4(1):65–80. | ||

Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1714–1721. | ||

Poulsen MG, Poulsen AA, Khan A, Poulsen EE, Khan SR. Work engagement in cancer workers in Queensland: the flip side of burnout. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2011;55(4):425–432. | ||

Epstein RM, Krasner MS. Physician resilience: what it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Acad Med. 2013;88(3):301–303. | ||

Jones MC, Wells M, Gao C, Cassidy B, Davie J. Work stress and well-being in oncology settings: a multidisciplinary study of health care professionals. Psychooncology. 2013;22(1):46–53. | ||

Gulati S, Dix D, Klassen A. Demands and rewards of working within multidisciplinary teams in pediatric oncology: the experiences of Canadian health care providers. Qual Rep. 2014;;36:1–15. | ||

Leung J, Rioseco P, Munro P. Stress, satisfaction and burnout amongst Australian and New Zealand radiation oncologists. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2015;59(1):115–124. | ||

Montgomery A, Spânu F, Băban A, Panagopoulou E, Demands J. Job demands, burnout, and engagement among nurses: a multi-level analysis of ORCAB data investigating the moderating effect of teamwork. Burn Res. 2015;2(2–3):71–79. | ||

Rushton CH, Batcheller J, Schroeder K, Donohue P. Burnout and resilience among nurses practicing in high-intensity settings. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(5):412–420. | ||

Broom A, Wong WK, Kirby E, et al. A qualitative study of medical oncologists’ experiences of their profession and workforce sustainability. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166302. | ||

Mater UQ Centre for Primary Health Care Innovation. My Health: A Doctors’ Wellbeing Survey. Brisbane: Metro South Hospital and Health Service, Queensland Government; 2016. | ||

Wu S, Singh-Carlson S, Odell A, Reynolds G, Su Y. Compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among oncology nurses in the United States and Canada. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2016;43(4):E161–E169. | ||

Hall LH, Johnson J, Heyhoe J, Watt I, Anderson K, O’Connor DB. Exploring the impact of primary care physician burnout and well-being on patient care. J Patient Saf. Epub 2017 Nov 14. | ||

Mullins N, Mcqueen L. Does compassion fatigue affect nurse educators in practice? Nurs Health. 2017;5(1):18–20. | ||

Rizo-Baeza M, Mendiola-Infante SV, Sepehri A, Palazón-Bru A, Gil-Guillén VF, Cortés-Castell E. Burnout syndrome in nurses working in palliative care units: an analysis of associated factors. J Nurs Manag. 2018;26(1):19–25. | ||

Girgis A, Hansen V, Goldstein D. Are Australian oncology health professionals burning out? A view from the trenches. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(3):393–399. | ||

Zander M, Hutton A, King L. Coping and resilience factors in pediatric oncology nurses. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2010;27(2):94–108. | ||

Hecktman HM. Stress in pediatric oncology nurses. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2012;29(6):356–361. | ||

Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Develop Int. 2009;14(3):204–220. | ||

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422. | ||

Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. | ||

Maslach C. Understanding job burnout. In: Rossi AM, Perrewe PL, Sauter SL, editors. Stress and Quality of Working Lfe: Current Perspectives in Occupational Health. Greenwich. CT: Information Age Publishing; 2006. | ||

Perlo J, Balik B, Swensen S, Kabcenell A, Landsman J, Feeley D. IHI Framework for Improving Joy in Work. IHI White Paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2017. Available from: http://www.ihi.org. Accessed March 16, 2018. | ||

van Breda A. A critical review of resilience theory and its relevance for social work. Soc Work. 2018;54(1). | ||

Joyce S, Shand F, Tighe J, Laurent SJ, Bryant RA, Harvey SB. Road to resilience: a systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e017858. | ||

Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience: a review and critique of definitions, concepts and theory. Eur Psychol. 2013;18(1):12–23. | ||

Neal D. Caring for Caregivers: Enhancing Compassion Satisfaction and Minimizing Fatigue, Secondary Traumatic Stress, and Other Adverse Impacts of Caregiving. California: Sati Centre, Institute for Buddhist Studies; 2012. | ||

Hill RC, Dempster M, Donnelly M, Mccorry NK. Improving the wellbeing of staff who work in palliative care settings: a systematic review of psychosocial interventions. Palliat Med. 2016;30(9):825–833. | ||

Morrison CF, Morris EJ. The practices and meanings of care for nurses working on a pediatric bone marrow transplant unit. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2017;34(3):214–221. | ||

Zadeh S, Gamba N, Hudson C, Wiener L. Taking care of care providers: a wellness program for pediatric nurses. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2012;29(5):294–299. | ||

Awa WL, Plaumann M, Walter U. Burnout prevention: a review of intervention programs. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(2):184–190. | ||

Poulsen MG, Poulsen AA, Khan A, Poulsen EE, Khan SR. Factors associated with subjective well-being in cancer workers in Queensland. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2012;56(3):347–353. | ||

Sabo BM. Compassionate presence: the meaning of hematopoietic stem cell transplant nursing. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(2):103–111. | ||

Klassen A, Gulati S, Dix D. Health care providers’ perspectives about working with parents of children with cancer: a qualitative study. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2012;29(2):92–97. | ||

Bowden MJ, Mukherjee S, Williams LK, Degraves S, Jackson M, Mccarthy MC. Work-related stress and reward: an Australian study of multidisciplinary pediatric oncology healthcare providers. Psychooncology. 2015;24(11):1432–1438. | ||

Mota Vargas R, Mahtani-Chugani V, Solano Pallero M, Rivero Jiménez B, Cabo Domínguez R, Robles Alonso V. The transformation process for palliative care professionals: the metamorphosis, a qualitative research study. Palliat Med. 2016;30(2):161–170. | ||

Horner JK, Piercy BS, Eure L, Woodard EK. A pilot study to evaluate mindfulness as a strategy to improve inpatient nurse and patient experiences. Appl Nurs Res. 2014;27(3):198–201. | ||

Shennan C, Payne S, Fenlon D. What is the evidence for the use of mindfulness-based interventions in cancer care? A review. Psychooncology. 2011;20(7):681–697. | ||

Raab K, Mindfulness RK. Mindfulness, self-compassion, and empathy among health care professionals: a review of the literature. J Health Care Chaplain. 2014;20(3):95–108. | ||

Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999;282(9):833–839. | ||

Slater PJ, Edwards RM. Needs analysis and development of a staff wellbeing program in a pediatric oncology, palliative care and hematology service. J Healthc Leadersh. In press. | ||

Queensland Government [homepage on the Internet]. Brisbane: Working for Queensland Survey. [updated 2018 May 18]. Available from: https://www.forgov.qld.gov.au/working-queensland-survey. Accessed June 10, 2018. | ||

Taylor J, Aldridge J. Exploring the rewards and challenges of paediatric palliative care work – a qualitative study of a multi-disciplinary children’s hospice care team. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16(1):73. | ||

Macpherson CF. Peer-supported storytelling for grieving pediatric oncology nurses. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2008;25(3):148–163. | ||

Altounji D, Morgan H, Grover M, Daldumyan S, Secola R. A self-care retreat for pediatric hematology oncology nurses. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2013;30(1):18–23. | ||

Kuglin Jones A, Kuglin J. Oncology nurse retreat: a strength-based approach to self-care and personal resilience. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21(2):259–262. | ||

Wei J, Rosen P, Greenspan JS. Physician burnout: what can chairs, chiefs and institutions do? J Pediatr. 2016;175:5–6. | ||

Noone SJ, Hastings RP. Building psychological resilience in support staff caring for people with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disab. 2009;13(1):43–53. | ||

Kravits K, Mcallister-Black R, Grant M, Kirk C. Self-care strategies for nurses: a psycho-educational intervention for stress reduction and the prevention of burnout. Appl Nurs Res. 2010;23(3):130–138. | ||

Mahon MA, Mee L, Brett D, Dowling M. Nurses’ perceived stress and compassion following a mindfulness meditation and self compassion training. J Res Nurs. 2017;22(8):572–583. | ||

Isaksson Rø KE, Gude T, Tyssen R, Aasland OG. A self-referral preventive intervention for burnout among Norwegian nurses: one-year follow-up study. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(2):191–197. | ||

Moody K, Kramer D, Santizo RO, et al. Helping the helpers: mindfulness training for burnout in pediatric oncology – a pilot program. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2013;30(5):275–284. | ||

Irving JA, Dobkin PL, Park J. Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: a review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2009;15(2):61–66. | ||

Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284–1293. | ||

Ponte PR, Koppel P. Cultivating mindfulness to enhance nursing practice. Am J Nurs. 2015;115(6):48–55. | ||

van Wyk B, Pillay-Van Wyk V. Preventive staff-support interventions for health workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;17(3):CD003541. | ||

Patterson K, Grenny J, McMillan R, Switzler A. Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012. |

Supplementary materials

| Figure S1 Standard evaluation form used for the well-being education workshops |

| Figure S2 Evaluation form for mindfulness sessions |

Oncology Staff Well-being Program Outcomes – September 2017

(You can also complete this survey online at the link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/oncwellbeing)

| Figure S3 Oncology Staff Well-being Outcomes Survey |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.