Back to Journals » Biologics: Targets and Therapy » Volume 13

Efficacy of adalimumab as second-line therapy in a pediatric cohort of Crohn’s disease patients who failed infliximab therapy: the Italian Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition experience

Authors Alvisi P, Arrigo S, Cucchiara S, Lionetti P, Miele E, Romano C, Ravelli A, Knafelz D, Martelossi S, Guariso G, Accomando S, Zuin G, De Giacomo C, Balzani L, Gennari M, Aloi M

Received 8 August 2018

Accepted for publication 28 November 2018

Published 3 January 2019 Volume 2019:13 Pages 13—21

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/BTT.S183088

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Doris Benbrook

Patrizia Alvisi,1 Serena Arrigo,2 Salvatore Cucchiara,3 Paolo Lionetti,4 Erasmo Miele,5 Claudio Romano,6 Alberto Ravelli,7 Daniela Knafelz,8 Stefano Martelossi,9 Graziella Guariso,10 Salvatore Accomando,11 Giovanna Zuin,12 Costantino De Giacomo,13 Lucio Balzani,14 Monia Gennari,15 Marina Aloi3

On behalf of the SIGENP IBD Working Group

1Pediatric Gastroenterology Unit, Pediatric Department, Maggiore Hospital, Bologna, Italy; 2Pediatric Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Unit, G Gaslini Children’s Hospital, Genoa, Italy; 3Pediatric Gastroenterology and Liver Unit, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy; 4Gastroenterology and Nutrition Unit, Meyer Children’s Hospital, Florence, Italy; 5Pediatric Department, Federico II University of Naples, Naples, Italy; 6Pediatric Gastroenterology, University of Messina, Messina, Italy; 7Gastroenterology and GI Endoscopy Unit, University Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital, Brescia, Italy; 8Hepatology and Gastroenterology Unit, Bambino Gesù Hospital, Rome, Italy; 9Department of Pediatrics, Institute of Child Health, IRCSS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy; 10University of Padua, Padua, Italy; 11Pediatric Department, University of Palermo, G di Cristina Children’s Hospital, Palermo, Italy; 12Pediatric Unit, Buzzi Hospital, Milan, Italy; 13Pediatric Unit, Niguarda Hospital, Milan, Italy; 14Morgagni Hospital, Forlì, Italy; 15Emergency Pediatric Department, S Orsola Hospital, Bologna, Italy

Background: Adalimumab (Ada) treatment is an available option for pediatric Crohn’s disease (CD) and the published experience as rescue therapy is limited.

Objectives: We investigated Ada efficacy in a retrospective, pediatric CD cohort who had failed previous infliximab treatment, with a minimum follow-up of 6 months.

Methods: In this multicenter study, data on demographics, clinical activity, growth, laboratory values (CRP) and adverse events were collected from CD patients during follow-up. Clinical remission (CR) and response were defined with Pediatric CD Activity Index (PCDAI) score ≤10 and a decrease in PCDAI score of ≥12.5 from baseline, respectively.

Results: A total of 44 patients were consecutively recruited (mean age 14.8 years): 34 of 44 (77%) had active disease (mean PCDAI score 24.5) at the time of Ada administration, with a mean disease duration of 3.4 (range 0.3–11.2) years. At 6, 12, and 18 months, out of the total of the enrolled population, CR rates were 55%, 78%, and 52%, respectively, with a significant decrease in PCDAI scores (P<0.01) and mean CRP values (mean CRP 5.7 and 2.4 mL/dL, respectively; P<0.01) at the end of follow-up. Steroid-free remission rates, considered as the total number of patients in CR who were not using steroids at the end of this study, were 93%, 95%, and 96% in 44 patients at 6, 12, and 18 months, respectively. No significant differences in growth parameters were detected. In univariate analysis of variables related to Ada efficacy, we found that only a disease duration >2 years was negatively correlated with final PCDAI score (P<0.01). Two serious adverse events were recorded: 1 meningitis and 1 medulloblastoma.

Conclusion: Our data confirm Ada efficacy in pediatric patients as second-line biological therapy after infliximab failure. Longer-term prospective data are warranted to define general effectiveness and safety in pediatric CD patients.

Keywords: pediatric Crohn’s disease, infliximab failure, adalimumab efficacy, adalimumab safety

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic, relapsing disease of the gastrointestinal tract affecting mainly young patients. In the past few decades, its incidence rate in the pediatric population has increased to 0.1–13.9 per 100,000 persons.1 Pediatric CD is characterized by frequent relapses, a wide extent of disease, a severe clinical course, and a high prevalence of extraintestinal manifestations. Almost a third of affected children present moderate–severe disease requiring a more aggressive therapeutic strategy to induce and maintain remission. However, treating CD is a major challenge for clinicians, as no curative therapy currently exists. Conventional therapy includes the use of corticosteroids, which are very effective and fast-acting; however, long-term exposure leads to drug dependence and/or resistance.2 Furthermore, corticosteroids carry a substantial risk of developing side effects, with growth retardation being one of the major concerns in pediatric CD patients.2,3 Immunomodulators, such as thiopurines and methotrexate, have proved to be effective in maintaining CD remission and sparing steroids.4,5 In particular, thiopurines are successful in about 70% of CD patients,6 but still primary or secondary nonresponders need alternative treatment.

Anti-TNFα antibodies represent a valid therapeutic option for pediatric patients affected by CD disease. Indeed, infliximab (Ifx) has been thoroughly evaluated in the past decade, with first data published in 2007.7 However, it has been shown that not all patients initially respond to Ifx (ie, primary failure), and a subset of patients discontinue Ifx as a consequence of loss of response or intolerance (ie, secondary failure).8 Recent data report that about 30% of patients lose response within 3 years after starting Ifx and almost 50% need dose escalation.9,10 Also, adalimumab (Ada) has demonstrated its effectiveness in treating CD patients in randomized clinical trials carried out in both adult and pediatric patients.11–16 However, since Ada was definitively approved by the European Medicines Agency for pediatric CD only in November 2012, real-life data on Ada clinical efficacy, its effect on growth status, and its safety profile are scarce, especially in patients who have failed Ifx therapy. The purpose of our study consisted in assessing the safety and efficacy of Ada as a second-line biological therapy in pediatric CD patients who had failed or were intolerant to Ifx.

Methods

Study design

We performed a retrospective, multicenter, cohort analysis of 44 CD pediatric patients with moderate–severe CD activity who had been treated with Ifx and were switched to Ada because of primary or secondary failure in 13 Italian pediatric gastroenterology centers. These centers were geographically well distributed throughout the country and were all affiliated with the Italian Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (SIGENP). All SIGENP centers were recruited by email correspondence and a questionnaire provided to the participants in autumn 2014. A new recall was made in April 2015 further to obtain the most recent follow-up data. Data collection was authorized by the ethics committees and written informed consent obtained for each study subject by parents. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

To be eligible for the study, patients had to fulfill criteria of CD diagnosed according to the recognized international criteria,17 age <18 years at the time of first Ada administration, disease location defined by the Paris classification,18 primary or secondary failure to Ifx treatment, and a follow-up of at least 6 months. In cases of secondary failure, loss of response was defined as an increase in Pediatric CD Activity Index (PCDAI) score compared to baseline, whereas subjects were deemed intolerant once they had experienced a clinically significant acute (within 24 hours) or delayed (>24 hours, but within 15 days) infusion reaction.

Study outcomes

The primary end point was to evaluate Ada clinical efficacy in the studied population through assessing PCDAI scores at 6, 12, and 18 months. Secondary end points included the collection of adverse events, changes in CRP, and weight and growth trends during a follow-up of at least 18 months. Clinical complete remission was defined by a PCDAI score ≤10, clinical response for PCDAI score >10, and a decrease in PCDAI score ≥12.5 points from baseline, because a decrease in PCDAI of 12.5 points has been revealed as the smallest change associated with physician assessment of at least moderate improvement, and thus the best value to be used, in order to capture both clinical remission and clinical response.19–21 No response in the case of persistently active disease was defined by a PCDAI score ≥10 or by a decrease in PCDAI score <12.5 points assessed at different times points throughout the study and in cases of relapse. Steroid-free remission consisted in clinical remission without the use of budesonide or other steroids. Steroid dependency was defined as the inability to stop systemic steroids within 3 months, or recurrence within 3 months from steroid withdrawal.

Data collected included demographics, disease extension, phenotype (Paris classification), presence of perianal disease, PCDAI, body-mass index (BMI), height, previous and concomitant medications (corticosteroids, immunomodulators), data regarding previous Ifx therapy (dosage, duration, treatment response, reasons for discontinuation), and dose escalation related to Ada therapy. All anthropometric data were converted into SD scores calculated on the basis of Italian growth-chart references and are expressed as means ± SD. Data on growth and weight were specifically recorded at diagnosis (T0), when Ada was initiated (Ada start), and at 6 (T6) and 18 months (T18). Disease severity, defined according to PCDAI score, and treatments were analyzed in relation to growth measures. Acute and delayed (reaction >24 hours after drug injection) intolerance toward Ada was evaluated. In addition, adverse events were reported by each center’s investigators.

Statistical analysis

All data were summarized and are displayed as means ± SD for continuous variables.22 Categorical data are expressed as frequencies and percentages, while possible missing data have been excluded from the analysis. In order to compare mean values of PCDAI scores at different moments of the study, Student’s t-test was implemented for paired samples, with equality in PCDAI mean values at different times the null hypothesis. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare potential prognostic factors for positive or negative responses at follow-ups. This choice was due to the limited number of statistical units, which prevented us from safely using standard parametric tests to investigate the proportion of subjects in remission at different times during the course of the study in the two groups of each identified prognostic factor. Still, despite the reduced number of units, Kaplan–Meier survival analyses with log-rank tests were run to show the trend of length of stay in the study of such cohort. The P-value was set at 0.05 for significance for all statistical tests. Finally, moving from a one-dimensional to a multidimensional approach, a multiple logistic model with positive or negative response at each follow-up as dependent variables was used for multivariate analysis.

Results

Demographic and clinical data at baseline

A total of 44 of 56 CD patients (78%) were enrolled, with the 12 excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria: eight were older than 18 years when Ada therapy was started, three had had follow-up <6 months, and one was anti-TNF-naïve. The main baseline characteristics of the CD patients are summarized in Table 1. The whole cohort had previously been treated with Ifx at the standard dose of 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks after induction. The mean number of infusions was nine (two to 28) for an average treatment period of 12 months. Ifx was adopted as first-line therapy in eight of 44 (18%), whereas 35 (80%) where treated after immunomodulator failure. One patient (2%) received Ifx after failure of both immunomodulators and thalidomide. In 23 cases (52%), Ifx was discontinued due to loss of efficacy (three of 23 primary nonresponders, 20 of 23 secondary nonresponders), whereas 21 (48%) stopped Ifx because of related adverse events.

| Table 1 Patient demographics at diagnosis and treatment before Ada Abbreviations: Ada, adalimumab; PCDAI, Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index. |

Adalimumab data

Treatment

Mean age at first Ada injection was 14.8 (range 9.9–17.1, median 14.7) years, with mean time from CD diagnosis of 3.4 years (4 months to 11.2 years, median 3.5 years). Mean follow-up was 12 (range 6–18) months. At baseline, of 44 patients, 34 (77%) had active disease according to their PCDAI score (mean 24.9), whereas ten patients (23%) were in clinical remission. Dosage was based on body weight. A total of 34 patients (77%) received a subcutaneous loading-dose regimen at weeks 0 and 2 as induction. In the 34 patients with active disease, the loading dose consisted of 80 mg/40 mg in 19 patients, 160 mg/80 mg in ten, and 120 mg/80 mg in five. The remaining ten patients were in clinical remission, so did not receive any induction doses and stopped Ifx therapy for allergic reactions.

The maintenance dose was 40 mg every 2 weeks. Dose escalation (80 mg every 2 weeks) was required in three patients and followed by dose de-escalation after 2 months, because of regaining of response. Concomitant immunomodulators were used in ten of 44 (22%) cases (six received azathioprine and four methotrexate). These agents were used in combination with Ada throughout the entire study period.

Follow-up

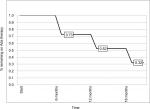

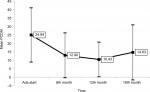

The Ada-persistence rate was 100% (44 patients), 73% (32 patients), and 52% (23 patients) at 6, 12 and 18 months, respectively (Figure 1). Among persisting patients, complete remission was achieved in 24 (55%), 25 (78%), and 12 (52%) cases and a clinical response in nine (20%), four (12.5%), and two (8.7%) patients at 6, 12, and 18 months, respectively (Figure 2). Mean PCDAI scores had decreased significantly at 6 and 12 months (12.9 and 10.4, P<0.01; Figure 3). CRP median values decreased significantly from baseline throughout the whole follow-up period (5.7 mg/dL at baseline vs 2.3 mg/dL at 6 months vs 2.3 mg/dL at 12 months vs 2.4 mg/dL at 18 months).

| Figure 1 Kaplan–Meier analysis of probability of remaining on Ada therapy during follow-up. Abbreviation: Ada, adalimumab. |

| Figure 2 Rates of clinical remission, clinical response and failure of Ada in 44 children with Crohn’s disease on Ada therapy. Abbreviation: Ada, adalimumab. |

| Figure 3 Mean PCDAI-value trend (with SD, P<0.01). Abbreviations: Ada, adalimumab; PCDAI, Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index. |

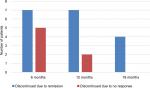

Eight of the ten patients in remission at baseline maintained clinical remission status throughout the whole study period, while two relapsed. Eighteen of 34 patients (53%) with active disease despite Ifx therapy at baseline achieved clinical remission during Ada treatment. (Figure 4). All primary nonresponders to Ifx reported clinical remission during the study. Therapy discontinuation because of complete remission was recorded in 16 patients and for Ada failure in six patients. Two patients discontinued treatment because of serious adverse events after 6 months. These data are shown in Figure 5.

| Figure 4 18-Month Ada-therapy follow-up in 44 patients with Crohn’s disease. Abbreviation: Ada, adalimumab. |

| Figure 5 Rates of adalimumab discontinuation due to remission or to no response. |

Steroid dependence

During Ifx treatment, 7/44 (16%) patients were steroid-dependent and seven (16%) also on steroid therapy at the beginning of Ada treatment. Of all enrolled patients, during Ada treatment, the steroid-free remission rate was 93%, 95%, and 96% at 6, 12, and 18 months follow-up respectively, and there was no steroid dependency in any patients.

Prognostic factors

We analyzed multiple prognostic factors : sex, age and weight at diagnosis, time between diagnosis and first Ada injection (<2 years and >2 years), disease location at diagnosis, combined therapies, and reasons for Ifx withdrawal (allergic reaction, loss of response). Time between diagnosis and first Ada injection was the only factor reaching statistical significance (P<0.01), with better prognosis for those subjects who started Ada within 2 years from diagnosis.

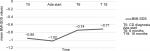

Growth

At baseline, the mean height of enrolled patients was 154.1 cm (128–180 cm, mean ± SD 0.91±1.27), mean weight 44.7 kg (24–70 kg, SD 1.3±1.54) and average BMI 18.5 kg/m2 (13.8–25.7, SD 1.02±1.35). At the end of the study, mean weight was 48.8 kg (27–75 kg, SD –0.99±1.46) and average BMI 19.4 kg/m2 (14.3–25.9, SD –0.71±1.1), although no significant changes in terms of linear growth were recorded (mean height 157.1 [128–180] cm, SD –0.83±1.37). BMI showed a trend toward increase (Figure 6).

| Figure 6 Mean standardized body mass index (BMI) SD score (SDS) before starting adalimumab (Ada) and during the 18-month follow-up. |

Safety profile

In our study population, two of 44 patients (4.5%) suffered adverse events that led to Ada discontinuation. There was a single case of bacterial meningitis in a patient under a combination regimen (Ada plus methotrexate), whereas another subject was diagnosed with a central nervous system (CNS) malignancy (medulloblastoma). No acute reaction was recorded. We had only one case of self-limiting injection-site reaction.

Discussion

Ada is an anti-TNF agent the efficacy of which in obtaining clinical remission in pediatric CD patients has been demonstrated in various studies.16,23,24 However, these studies had some drawbacks (ie, use of different scales to assess disease severity, concurrent presence of naïve and Ifx-failure patients, short follow-up, limited sample size) that limit their generalization in clinical practice and the possibility of comparisons among them. Therefore, we decided to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Ada in a multicenter cohort of patients. The major finding of our study was that even in an anti-TNF-experienced population, Ada treatment induced clinical remission in more than half the cases, with 18 patients reverting from active disease after Ifx treatment into clinical remission at 18 months, including Ifx primary nonresponders. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, the current study had the longest follow-up for Ada-treated patients published in medical literature.16,23,24

At the latest follow up of 18 months, Ada had induced clinical remission in 52% of enrolled patients, with a remission rate of 78% at 12 months and 55% at 6 months. Moreover, we observed that 18 of the 34 patients with active disease despite Ifx treatment (53%) achieved clinical remission during Ada therapy (Figure 4). These remission rates are comparable to previously published data. Indeed, in Russell et al,24 the remission rate was 58% at 6 months, whereas the RESEAT study showed an 80% remission rate at 12 months.16 The Dutch PIBD Working Group reported 64% and 50% remission rates at 3.3 and 24 months, respectively,25 whereas Fumery et al reported Ada efficacy in 70% of their studied population.21 These results have been summarized in a recent systematic review.26

Therapy discontinuation because of complete remission was recorded in 16 of 44 patients (36%) and for serious events in two patients at 6 months. On the other hand, 18% of patients showed no response and discontinued therapy, confirming previous pediatric investigations.20 In particular, we found that loss of response and recurrence of disease activity during anti-TNFα therapy may occur in 15%–28% of the pediatric population within 12 months of Ada therapy.20 We observed a better remission rate at 12 months than 6 months, mainly because six nonresponders stopped Ada treatment during the first 6 months.

Another important finding of our study is the high corticosteroid-free remission rate (96%) at the last follow-up, while during Ifx therapy 16% of our population was steroid-dependent. This result is very important, because steroid use has significant impact on growth development in young patients. Indeed, in terms of the rate of linear growth, we did not find a significant difference in parameters considered at the end of treatment, both for the general cohort and the sex subgroups. However, we found a positive trend for BMI, with a mild improvement in weight gain in the female subgroup (P=0.047). Of note, when Ada was started, the study population had a mean age of 14.8 years, and thus the pubertal growth spurt already began. This reason could actually reflect a catch-up growth deficit. Unfortunately, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry-derived data, such as Z-scores, were not available for the analysis.

As to the safety of Ada therapy, in our series there were two major adverse events: one case of meningitis and one neoplasm of the CNS. In other studies, the overall serious adverse-event rate was 2.5%–6%, and no cases of CNS neoplasm were reported.26,27 In our cohort, the patient who developed meningitis was receiving combination therapy (Ada plus methotrexate) and stopped Ada after 6 months. According to some authors, apparently there would not be an increasing risk of serious infections between patients receiving combination therapy (anti-TNF plus immunomodulators) and those on monotherapy (OR 0.37).28 However, such data are ambiguous in the literature: different authors have reported a higher risk of opportunistic infections (OR 14.5, 95% CI 4.9–43) when two or three immunosuppressants were associated.29 More importantly, the severity of CD itself may play a role in predisposition to serious infections.30,31 Severity and prolongation of the disease could have predisposed our patient to a serious infection, such as meningitis. According to this theory, he had active and prolonged severe disease (PCDAI 40), at the time of infection. Regarding our case of CNS neoplasm, a medulloblastoma arose in a young patient diagnosed with severe CD treated with Ifx as first-line therapy for 8 months, and after a serious allergic reaction being switched to Ada. This patient was never treated with immunomodulators in combination with anti-TNF drugs. Actually, there have been no reported cases of medulloblastoma or other CNS malignancies in patients affected by inflammatory bowel disease treated with anti-TNF, although it is almost impossible to correlate the use of anti-TNF with this type of cancer.

With regard to prognostic factors, the only variable that reached statistical significance was the short interval (<2 years) between diagnosis and Ada administration. In line with our data, the literature reports that Ada seems to work more effectively when introduced in an early stage of the disease.32 Probably, the natural history of the disease and its prognosis could benefit by prompt implementation of Ada.

Some important study limitations should be noted. Firstly, the limited sample size (n=44) may have limited the statistical power of the study. Secondly, we did not evaluate serum drug levels of anti-Ada antibodies to investigate a potential mechanism of loss of response, even if a recent CD trial showed no advantage in steroid-free remission in patients in which Ifx dose was increased based on therapeutic drug level.33 This study was a prospective randomized controlled trial that demonstrated that increasing Ifx levels above 3 mcg/ml did not produce higher rates of endoscopic or clinical remission in active luminal CD. Third, we did not measure fecal calprotectin to have surrogate data on the status of gastrointestinal mucosa. However, these latter two tests were not available at the time the study was undertaken in the majority of the centers involved.

In conclusion, our data confirm the efficacy of Ada in Ifx refractory/intolerant pediatric patients affected by CD. Longer prospective studies are warranted to define the general effectiveness and safety of Ada in pediatric patients with CD.

Acknowledgments

Ilaria Cocchi organized the database and helped to analyze data. A portion of these data was presented as a poster at the ECCO Congress, February 14–16, 2015, Vienna.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Benchimol EI, Fortinsky KJ, Gozdyra P, Van den Heuvel M, Van Limbergen J, Griffiths AM. Epidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of international trends. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(1):423–439. | ||

Markowitz J, Hyams J, Mack D, et al. Corticosteroid therapy in the age of infliximab: acute and 1-year outcomes in newly diagnosed children with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(9):1124–1129. | ||

Ruemmele FM, Veres G, Kolho KL, et al. Consensus guidelines of ECCO/ESPGHAN on the medical management of pediatric Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(10):1179–1207. | ||

Hyams JS, Markowitz J, Wyllie R. Use of infliximab in the treatment of Crohn’s disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2000;137(2):192–196. | ||

Turner D, Grossman AB, Rosh J, et al. Methotrexate following unsuccessful thiopurine therapy in pediatric Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(12):2804–2812. | ||

Barabino A, Torrente F, Ventura A, Cucchiara S, Castro M, Barbera C. Azathioprine in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease: an Italian multicentre survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(6):1125–1130. | ||

Hyams J, Crandall W, Kugathasan S, et al. Induction and maintenance infliximab therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease in children. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(3):863–873. | ||

Hanauer SB, Wagner CL, Bala M, et al. Incidence and importance of antibody responses to infliximab after maintenance or episodic treatment in Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(7):542–553. | ||

Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(1):52–65. | ||

Hyams JS, Lerer T, Griffiths A, et al. Long-term outcome of maintenance infliximab therapy in children with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(6):816–822. | ||

Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn’s disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(2):323–333. | ||

Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Rutgeerts P, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance treatment of Crohn’s disease: results of the CLASSIC II trial. Gut. 2007;56(9):1232–1239. | ||

Martín-de-Carpi J, Pociello N, Varea V. Long-term efficacy of adalimumab in paediatric Crohn’s disease patients naïve to other anti-TNF therapies. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4(5):594–598. | ||

Ho GT, Smith L, Aitken S, et al. The use of adalimumab in the management of refractory Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(4):308–315. | ||

Viola F, Civitelli F, Di Nardo G, et al. Efficacy of adalimumab in moderate-to-severe pediatric Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(10):2566–2571. | ||

Rosh JR, Lerer T, Markowitz J, et al. Retrospective Evaluation of the Safety and Effect of Adalimumab Therapy (RESEAT) in pediatric Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(12):3042–3049. | ||

Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, et al. ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58(6):795–806. | ||

Levine A, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, et al. Pediatric modification of the Montreal classification for inflammatory bowel disease: the Paris classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(6):1314–1321. | ||

Noe JD, Pfefferkorn M. Short-term response to adalimumab in childhood inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(12):1683–1687. | ||

Wyneski MJ, Green A, Kay M, Wyllie R, Mahajan L. Safety and efficacy of adalimumab in pediatric patients with Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47(1):19–25. | ||

Fumery M, Jacob A, Sarter H, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab after infliximab failure in pediatric Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60(6):744–748. | ||

Papp KA, Fonjallaz P, Casset-Semanaz F, Krueger JG, Mittkowski KM. Approaches to reporting long-term data. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:2001–2008. | ||

Hyams JS, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, et al. Safety and efficacy of adalimumab for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease in children. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(2):365–374. | ||

Russell RK, Wilson ML, Loganathan S, et al. A British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition survey of the effectiveness and safety of adalimumab in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(8):946–953. | ||

Cozijnsen M, Duif V, Kokke F, et al. Adalimumab therapy in children with Crohn disease previously treated with infliximab. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60(2):205–210. | ||

Dziechciarz P, Horvath A, Kierkuś J. Efficacy and Safety of Adalimumab for Paediatric Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(10):1237–1244. | ||

Williams CJ. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Ford AC. Systematic review with meta-analysis: malignancies with anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(5):447–458. | ||

Schreiber S, Reinsich R, Colombel J, et al. Early Crohn’s disease shows high levels of remission to therapy with adalimumab: sub-analysis of CHARM. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:A-147. | ||

Peyrin-Biroulet L, Deltenre P, de Suray N, Branche J, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Crohn’s disease: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(6):644–653. | ||

Lichtenstein GR, Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, et al. A pooled analysis of infections, malignancy, and mortality in infliximab- and immunomodulator-treated adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):1051–1063. | ||

Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious infection and mortality in patients with Crohn’s disease: more than 5 years of follow-up in the TREAT registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1409–1422. | ||

Deepak P, Stobaugh DJ, Ehrenpreis ED. Infectious complications of TNF- alfa inhibitor monotherapy versus combination therapy with immunomodulators in inflammatory bowel disease: analysis of the food and drug administration adverse event reporting system. J. Gastroenterol Liver Dis. 2013;22(3):269–276. | ||

D’Haens G, Vermeire S, Lambrecht G, et al. Increasing infliximab dose based on symptoms, biomarkers, and serum drug concentrations does not increase clinical, endoscopic, and corticosteroid-free remission in patients with active luminal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(5):1343–1351. |

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.