Back to Journals » Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity » Volume 12

Efficacy Of Acceptance And Commitment Therapy For Emotional Distress In The Elderly With Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Authors Maghsoudi Z , Razavi Z, Razavi M, Javadi M

Received 28 June 2019

Accepted for publication 2 October 2019

Published 17 October 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 2137—2143

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S221245

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Juei-Tang Cheng

Zahra Maghsoudi,1 Zohreh Razavi,2 Mohammadreza Razavi,1 Mostafa Javadi3

1Student Research Committee, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran; 2Saman Psychology Clinic, Yazd, Iran; 3Research Centre for Nursing and Midwifery Care, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

Correspondence: Mostafa Javadi

Nursing Department, Nursing and Midwifery School, Safaieh, Yazd, Iran

Tel +98 8 13 827 1145

Email [email protected]

Introduction: Diabetes is among the common diseases in the elderly which results in depression, anxiety, and emotional distress in the elderly and impacts the disease control by the individual. This study was conducted with the aim of exploring the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) in the improvement of emotional distress in the elderly with type 2 diabetes.

Materials and methods: In this randomized control trial, 80 elderly with type 2 diabetes aged ≥60 years were randomly selected among the individuals visiting Yazd Diabetes Research Center. Then, the patients were randomly divided into two 40 individual groups, ie, the intervention group and the control group. The intervention group underwent group ACT during eight 90-min sessions. The diabetes-related emotional distress questionnaire was completed before the intervention, after the end of the group sessions and 2 months after that. The statistical software SPSS version 21 was used for data analysis.

Results: The emotional mean scores in the intervention and control groups were not significantly different before the intervention. However, the mean score of the intervention group was lower than of the control group immediately after the intervention (p=0.02) and 2 months after the intervention (p=0.02).

Conclusion: ACT results in the improvement of diabetes-related emotional distress in the intervention group. Considering the effectiveness of ACT, this therapeutic method is recommended to be used for the amelioration of emotional distress in the elderly with type 2 diabetes.

Keywords: acceptance and commitment therapy, emotional distress, elderly

Introduction

Nowadays, due to advancements in medicine, the world is experiencing a new phenomenon called population aging.1 Population aging is considered as one of the main problems in the world today2 as due to the reduction of physical and physiological power, the chance of being afflicted with chronic physical and mental diseases and inability is increased in the elderly.3 Stress, anxiety and tension are more common in them due to a life full of the feeling of inadequacies and inabilities.4

Diabetes is the most common metabolic disease in the world5 and one of the main causes of death and inability in the elderly.6 In addition to physical problems such as retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy and diabetic foot,7 there are higher levels of emotional problems in individuals with type 2 diabetes which include depression, anxiety, aggression and emotional distress.8,9 According to studies, about 20% to 40% of patients with type 2 diabetes experience emotional distress.10,11

Emotional distress in individuals with type 2 diabetes is a worry and anxiety that is related to diabetes and exists from mild to severe level.12 Factors such as the difficulty of diagnosis, signs and strict care programs are considered as a source for emotional distress in patients with type 2 diabetes.13 Disease-related emotional distress can exist due to sad problems to self-care needs resulted from diabetes such as continuous glucose monitoring, taking medication, insulin injection, diet control and regular physical activity.14 The results of a study conducted in 13 countries indicate a high prevalence of this disorder.15

Emotional distress as a strong predicting factor in diabetes control can significantly impact health-related consequences of diabetes such as diabetic’s self-management and self-care performance.16,17 Therefore, it is necessary that nurses take effective steps to discover the impact of emotional distress on health consequences in individuals with type 2 diabetes.18

As controlling a chronic disease such as diabetes is not merely pharmacotherapy and is impacted by a complex network of behavioral, attitudinal and healthcare factor;19 it is necessary to use new therapeutic methods including the improvement of cognitive and behavioral skills in these patients in order to reduce psychological disorders.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) was introduced by Steven Hayes in 1986. This method is an approach from the third wave of behavioral therapies20 and its main message for the patient is that accept whatever is beyond personal control and be committed to an action that enriches his life.21 The main aim of ACT is not changing the form or frequency of disturbing thoughts and emotions; rather, it is improving psychological flexibility.22 Psychological flexibility means the individual’s ability to consciously be connected with the present despite all the feelings, thoughts, memories and bodily feelings experienced at the moment and doing behaviors that are in line with the individual’s selected objectives and values.22,23 ACT uses six core processes for psychological flexibility: acceptance, cognitive defusion, contact with the present moment, self as context, values and a committed.24 According to this therapy, efforts for having an anxiety-free life are impossible and result in isolation, failure and hopelessness. In fact, ACT is more impactful on thinking flexibility using a wide set of mindfulness and metaphor techniques and experimental practices instead of eliminating disturbing thoughts.25

With the increase of diabetes prevalence and elderly population in Iran in recent years, the need for planning for different aspects such as physical, mental, etc. in this population is felt.26,27 As several studies have supported the effectiveness of ACT in reducing the symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress,28–30 the present study aimed to determine the efficacy of ACT compared to routine educations and care provided in community therapeutic center on emotional distress in the elderly with type 2 diabetes.

Materials And Methods

This study was a randomized controlled trial with pretest–posttest design. The population of this study consisted of all individuals aged 60 and higher with diabetes type 2 referring to Research and Therapy Center for Diabetes of Yazd County – the main center for treatment of individuals with diabetes in Yazd Province in July 2018. On the basis of other studies, the sample size calculation was based on the assumption that a 2.5-point difference between ACP group and control group on the diabetes distress scale would be clinically significant. Assuming a standard deviation of 2.25 points, an alpha of 0.05 and a beta of 0.20 (power of 0.80), this analysis indicated that a sample size of at least 40 patients per group was necessary. For conducting the study, the researcher visited the Research and Therapy Center for Diabetes of Yazd County after the research design was verified and permissions were obtained from the Deputy Vice-Chancellor for Research and moral committee of the university with moral code No. IR.SSU.REC.1395.15.

First, a list of patients was prepared based on the computer registration system for individual with type 2 diabetes in the center. Then, patients who had inclusion criteria and were willing to participate in the study were selected using random number table. The criteria for inclusion in the study were: mean item score of 3 or higher, being over 60 years old, having diabetes type 2 for more than a year, being able to read and write and willingness to participate in the study and exclusion criteria were: having severe mental problem such as major depression disease, receiving any psychological treatment in the past year, having sever complications resulted from diabetes such as diabetic foot, severe ulcer, amputation, the use of narcotic drugs and drug abuse in the past month.

The individuals selected for the study were contacted for their agreement and they were given explanations about the duration of the study, the way the study is conducted, the objectives and the conditions of the study and the fact that they might be placed in a control or intervention group. All the participants submitted written informed consent for this study, based on the Declaration of Helsinki. After the initial sample individuals were determined, 40 individuals were allocated to the intervention group and 40 to the control group using random allocation software. As the number of individuals in group training has been reported to be 12 to 20 in different studies and as the number of the individuals in the intervention group in this study was 40, the individuals in the intervention group were divided into two 20 individual groups randomly. Then, the individuals were contacted to visit the Research and Therapy Center for Diabetes for completing the written consent form and the related questionnaires.

Demographic data and diabetes emotional distress questionnaires were completed by the control and the intervention groups as pretest before the intervention. The demographic questionnaire consisted of 6 questions related to the individual characteristics and the respondents’ disease, such as age, sex, education level, height, weight and the duration of having diabetes.

The Diabetes Distress Scale consisted of 17 questions and is measured by a six-point Likert-style scoring. This tool was prepared by Polonsky et al in the University of California for measuring the overall distress in patients with type 2 diabetes. The Cronbach’s alpha has been reported to be 0.87 for this scale in the main study. The seventeen items in this study are divided into four dimensions which are: emotional burden, physician-related distress, regimen-related distress and diabetes-related interpersonal distress. The scoring is from 1 (never) to 6 (always) for each item. The total score for this tool is between 17 and 102.31 The validity and reliability of this scale has been verified by ShojaeeZadeh et al in Iran and the Cronbach’s alpha for the whole scale is calculated as being equal to 0.75.32

The therapeutic intervention (ACT) for the intervention group was done in the form of group sessions during eight 90-min sessions, one session per week. If a participant was absent for two sessions, he/she would be excluded from the study. The contents of the interventional sessions are given in Table 1. The group training sessions were performed and administered by a clinical psychologist and a nurse. The control group did not receive these therapeutic interventions and they were only under routine educations and care in community therapeutic center.

|

Table 1 Session Contents Of ACT In The Intervention Group |

The questionnaires were completed again after the end of the sessions and then again 2 months after (follow-up test) for measuring the maintaining of the effect of therapeutic intervention by the intervention and the control group.

SPSS software version 21 was used for data analysis. Considering normal data dispersion, parametric tests were used in this study. Repeated measure ANOVA was used for the comparison of the changes of diabetes emotional distress before, immediately after and 2 months after the intervention and, considering its significance, the least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc test was used.

Findings

In this study, 40 individuals participated in the intervention group and 40 individuals participated in the control group. More of the patients in intervention group (57.5%) were male while females (52.5%) were more in control group. This difference was not statistically significant (p=0.8). Diploma was the most frequent level of education among the intervention (67.5%) and control (65%) groups (p=0.975). No significant statistical difference existed between the control and intervention groups in terms of the quantitative variables age, height, weight and duration of the disease (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Dispersion Of Demographic Variables In The Intervention And Control Groups |

Independent t-test indicated that emotional distress mean scores were not significantly different in the intervention and control groups before the intervention. However, after the intervention and 2 months after the intervention the emotional distress score in the intervention group was lower than that of the control group and the difference was statistically significant (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Mean And Standard Deviation Of Emotional Distress Score In The Intervention And Control Group In Different Times In The Study |

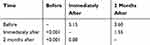

Repeated measure ANOVA indicated that the change of emotional distress mean score in the control group was not statistically significant in different times but a difference was seen in the intervention group in this regard: the post-hoc test LSD indicated that the emotional distress mean score after the intervention was reduced by 5.15 units, compared with before the intervention and the reduction was statistically significant (P<0.001). In addition, the emotional distress mean sore 2 months after the intervention was reduced by 3.60 units, compared with before the intervention and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.001). No significant statistical difference existed between emotional distress mean scores after the intervention and 2 months after the intervention (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Comparison Of Emotional Distress Mean Scores At Different Time In The Intervention Group* |

Discussion

In this study, the diabetes-related emotional distress levels were not significantly different in the intervention and control groups before the intervention. The level of diabetes-related emotional distress in the present study was consistent with the results of the studies by Polonsky et al31 Alvani et al33 and Chew et al.34

The diabetes-related emotional distress mean score was reduced after the intervention in the intervention group and this indicates that the ACT-based intervention has had a positive impact on diabetes-related emotional distress. Zucchelli et al,35 Davis et al,36 Rahnama et al37, Molander et al38 and Boostani et al39 have obtained similar results in their studies with the aim of exploring the impact of ACT on emotional distress and psychological distress in other patient.

The efficacy of ACT on other psychological disorders has also been verified. In two studies by Behrouz et al29 and Amsberg et al,40 the use of ACT was effective on the reduction of the symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress. In addition, ACT impacted hopelessness in the study by Sahebari et al41 and perceived stress and self-efficacy in the study by Moazzezi et al.42

The commitment to use emotional control, adherence to behavioral commitment, clarification of values and doing behaviors that are consistent with values that accompany expression of metaphors, defusion and acceptance during ACT can be effective in improving diabetes-related emotional distress. In this regard, the patients are helped to accept their thoughts and feelings and be committed to changes in their thoughts or behaviors. And thereby the patients are helped to consider disturbing thoughts as merely a thought, be aware that their previous behaviors have been ineffective and learn to take step in line with their values and for what is important for them rather than responding to the thoughts.

ACT teaches individuals to act for achieving their objectives and experience their thoughts and feelings instead of making efforts to stop their thoughts and feelings.

During this process, individual should learn to abandon the inhibition of thought, be free from disturbing thoughts and strengthen observing self instead of conceptualized self, accept events instead of controlling them and expression and deal with his values.

The results indicate that 2 months after the intervention, diabetes-related emotional distress has increased a little and this indicates that ACT should be done over time and needs follow-up sessions. Therefore, patients should undergo intervention again through follow-up sessions so that the therapy is not stopped and so that it maintains its effect.

The limitations of the study include the controlled conditions for the study and special characteristics of the sample (low number of single patients or patients who live alone, the low number of individuals with a relatively high level of education). In addition, the study is conducted on patients visiting Research and Therapy Center for Diabetes of Yazd County and therefore future studies are also recommended to explore the individual with type 2 diabetes who are dispersed in the society. Another limitation so the study was the short follow-up period (2 months) while ACT needs a long-term follow-up period (several months). In this study, we did not include another intervention in control group to compression with ACT. Therefore, finding our study indicated that ACT is associated with better outcome compared to routine education, which may be without any planning and therapeutic goals.

Conclusion

Considering the results, acceptance and commitment theory reduces the emotional distress in the elderly with diabetes type 2 and can be used as a psychological intervention together with other interventions. However, continuity of ACT is an important factor in its applying for reducing the diabetes-related emotional distress.

Acknowledgments

This study is a part of a master’s thesis in gerontological nursing approved by Yazd Shahid Sadoghi University of Medical Sciences and Health Services and the researchers hereby thank the deputy for research of Yazd Shahid Sadoghi University of Medical Sciences and Health Services for financial support, the Research and Therapy Center for Diabetes of Yazd County for giving the permission to conduct the study and the dear patients for their participation in the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Mohammadi MM, Esmaeilivand M. Attitudes toward caring of the elderly from the perspective of nursing and midwifery students in Kermanshah Province in 2015. Iran J Ageing. 2017;11:476–483.

2. Organization WH. World Report on Ageing and Health. World Health Organization; 2015.

3. Naseh L, Shaikhy R, Rafiei H. General self-efficacy and associated factors among elderly residents of nursing home. J Holistic Nurs Midwifery. 2016;26:90–97.

4. Hesamzadeh A, Maddah SB, Mohammadi F, Fallahi Khoshknab M, Rahgozar M. Comparison of elderlys” quality of life” living at homes and in private or public nursing homes. Iran J Ageing. 2010;4.

5. Mansori K, Shiravand N, Shadmani FK, et al. Association between depression with glycemic control and its complications in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13:1555–1560. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2019.02.010

6. Kooshyar H, Shoorvazi M, Dalir Z, Hosseini M. Health literacy and its relationship with medical adherence and health-related quality of life in diabetic community-residing elderly. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2014;23:134–143.

7. Parizad N, Hemmati MM, Khalkhali H. Promoting self-care in patients with type 2 diabetes: tele-education. Hakim Res J. 2013;16:220–227.

8. Khan P, Qayyum N, Malik F, Khan T, Khan M, Tahir A. Incidence of anxiety and depression among patients with Type 2 diabetes and the predicting factors. Cureus. 2019;11:e4254.

9. Iturralde E, Rausch JR, Weissberg-Benchell J, Hood KK. Diabetes-related emotional distress over time. Pediatrics. 2019;143:e20183011. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3011

10. Pandit AU, Bailey SC, Curtis LM, et al. Disease-related distress, self-care and clinical outcomes among low-income patients with diabetes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68:557–564. doi:10.1136/jech-2013-203063

11. Chew B-H, Vos RC, Pouwer F, Rutten GE. The associations between diabetes distress and self-efficacy, medication adherence, self-care activities and disease control depend on the way diabetes distress is measured: comparing the DDS-17, DDS-2 and the PAID-5. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;142:74–84. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2018.05.021

12. Devarajooh C, Chinna K, Khamseh ME. Depression, distress and self-efficacy: the impact on diabetes self-care practices. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175096. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0175096

13. Tol A, Sharifirad G, Eslami A, Shojaeizadeh D, Alhani F, Tehrani MM. Analysis of some predictive factors of quality of life among type 2 diabetic patients. J Educ Health Promot. 2015;4:9–15. doi:10.4103/2277-9531.151903

14. Spencer MS, Kieffer EC, Sinco BR, et al. Diabetes-specific emotional distress among African Americans and Hispanics with type 2 diabetes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17:88–105. doi:10.1353/hpu.2006.0095

15. Peyrot M, Rubin R, Lauritzen T, Snoek F, Matthews D, Skovlund S. Psychosocial problems and barriers to improved diabetes management: results of the cross‐national Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) Study. Diabetic Med. 2005;22:1379–1385. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01644.x

16. Schmitt A, Reimer A, Kulzer B, Haak T, Gahr A, Hermanns N. Negative association between depression and diabetes control only when accompanied by diabetes-specific distress. J Behav Med. 2015;38:556–564. doi:10.1007/s10865-014-9604-3

17. Sittner KJ, Greenfield BL, Walls ML. Microaggressions, diabetes distress, and self-care behaviors in a sample of American Indian adults with type 2 diabetes. J Behav Med. 2018;41:122–129. doi:10.1007/s10865-017-9898-z

18. Tol A, Shojaezadeh D, Eslami A, Alhani F, Mohajeri TM, SHarifirad GR. Analyses of some relevant predictors on self- managment of Type 2 diabetic patients. Hospital. 2011;10.

19. Izadi TA, Nemati DS, ND M. The relationship between attachment style on self-efficacy and self-care in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Nurs. 2014;1.

20. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1–25. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

21. Heidari A, Heidari H, Davoudi H. Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment-based therapy on the physical and psychological marital intimacy of women. Int J Educ Psychol Res. 2017;3:163. doi:10.4103/jepr.jepr_62_16

22. Hayes SC, Villatte M, Levin M, Hildebrandt M. Open, aware, and active: contextual approaches as an emerging trend in the behavioral and cognitive therapies. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7.

23. Arch JJ, Craske MG. Acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: different treatments, similar mechanisms? Clin Psychol. 2008;15:263–279.

24. Burckhardt R, Manicavasagar V, Batterham PJ, Hadzi-Pavlovic D. A randomized controlled trial of strong minds: A school-based mental health program combining acceptance and commitment therapy and positive psychology. J Sch Psychol. 2016;57:41–52. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2016.05.008

25. Wilson KG. Mindfulness for Two: An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Approach to Mindfulness in Psychotherapy. New Harbinger Publications; 2009.

26. Natovich R, Gayus N, Azmon M, et al. Supporting a comprehensive and coordinated evaluation of the elderly with diabetes by integrating cognitive and physical assessment in the evaluation process. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018;34:e3030. doi:10.1002/dmrr.3030

27. Kalra S, Sharma SK. Diabetes in the Elderly. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:493–500. doi:10.1007/s13300-018-0380-x

28. Graham CD, Gillanders D, Stuart S, Gouick J. An acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)–based intervention for an adult experiencing post-stroke anxiety and medically unexplained symptoms. Clin Case Stud. 2015;14:83–97. doi:10.1177/1534650114539386

29. Behrouz B, Bavali F, Heidarizadeh N, Farhadi M. The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on psychological symptoms, coping styles, and quality of life in patients with type-2 diabetes. J Health. 2016;7:236–253.

30. Kelson J, Rollin A, Ridout B, Campbell A. Internet-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy for anxiety treatment: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e12530. doi:10.2196/12530

31. Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Earles J, et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:626–631. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.3.626

32. Shojaeezadeh D. Effect of empowerment model on distress and diabetes control in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Nurs Educ. 2012;1:38–47.

33. Alvani SR, Zaharim NM, Kimura LW. Defining the relationship of psychological well-being and diabetes distress with glycemic control among Malaysian type 2 diabetes. Journal of Practice in Clinical Psychology. 2015;3:167–176.

34. Chew B-H, Vos R, Mohd-Sidik S, Rutten GE, Hashimoto K. Diabetes-related distress, depression and distress-depression among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Malaysia. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152095. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152095

35. Zucchelli F, Donnelly O, Williamson H, Hooper N. Acceptance and commitment therapy for people experiencing appearance-related distress associated with a visible difference: a rationale and review of relevant research. J Cogn Psychother. 2018;32:171–183. doi:10.1891/0889-8391.32.3.171

36. Davis EL, Deane FP, Lyons GC, Barclay GD, Bourne J, Connolly V. Feasibility randomised controlled trial of a self-help acceptance and commitment therapy intervention for grief and psychological distress in carers of palliative care patients. J Health Psychol. 2017;1–18.

37. Rahnama M, Sajjadian I, Raoufi A. The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on psychological distress and medication adherence of coronary heart patients. Iran J Psychiatr Nurs. 2017;5:34–42. doi:10.21859/ijpn-05045

38. Molander P, Hesser H, Weineland S, et al. Internet-based acceptance and commitment therapy for psychological distress experienced by people with hearing problems: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther. 2018;47:169–184. doi:10.1080/16506073.2017.1365929

39. Boostani M, Ezadikhah Z, Sadeghi M. Effectiveness of group-based acceptance and commitment therapy on the difficulty emotional regulation and distress tolerance patients with essential hypertension. Int J Educ Psychol Res. 2017;3:205. doi:10.4103/2395-2296.204118

40. Amsberg S, Wijk I, Livheim F, Toft E, Johansson UB, Anderbro T. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for adult type 1 diabetes management: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e022234. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022234

41. Sahebari M, Ebrahimabad MJA, Ahmadi A, Aghamohamadian HR, Khodashahi M. Efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy in reducing disappointment, psychological distress, and psychasthenia among Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients. Iran J Psychiatry. 2019;14:130–136.

42. Moazzezi M, Moghanloo VA, Moghanloo RA, Pishvaei M. Impact of acceptance and commitment therapy on perceived stress and special health self-efficacy in seven to fifteen-year-old children with diabetes mellitus. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2015;9:956–967. doi:10.17795/ijpbs956

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.