Back to Journals » Infection and Drug Resistance » Volume 11

Efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir–ledipasvir for treatment of a cohort of Egyptian patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 4 infection

Authors Ahmed OA, Kaisar HH, Badawi R, Hawash N, Samir H, Shabana SST, Fouad MHA, Rizk FH , Khodeir SA, Abd-Elsalam S

Received 2 October 2017

Accepted for publication 28 November 2017

Published 1 March 2018 Volume 2018:11 Pages 295—298

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S153060

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Suresh Antony

Ossama A Ahmed,1 Hany H Kaisar,1 Rehab Badawi,2 Nehad Hawash,2 Hossam Samir,1 Sherif ST Shabana,1 Mohamed Hassan A Fouad,1 Fatma H Rizk,3 Samy A Khodeir,4 Sherief Abd-Elsalam2

1Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt; 2Department of Tropical Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt; 3Physiology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt; 4Department of Internal Medicine, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt

Background and aims: Treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has significantly changed during the last few years. The combination of ledipasvir and sofosbuvir has been shown to treat high proportions of patients with HCV genotype 1 with remarkable tolerability. The aim of the work was to assess the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir plus ledipasvir in treating treatment-naïve Egyptian patients with genotype 4 HCV infection.

Patients and methods: In this open-label randomized study, 200 treatment-naive patients who were HCV antibody positive and HCV RNA positive by polymerase chain reaction, aged >18 years, were enrolled. The patients were classified into two groups: group I included 100 patients who received single therapy with sofosbuvir plus ledipasvir for 12 weeks and group II included 100 patients who received sofosbuvir plus oral weight-based ribavirin for 24 weeks. The primary end point was a sustained virological response at 12 weeks (SVR12) after the end of treatment, determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction for HCV RNA.

Results: Group I patients showed statistically significant (p<0.05) higher SVR12 compared with group II patients (99% vs. 80%). There was no statistical difference (p>0.05%) between the studied groups regarding the frequencies of the side effects (26% vs. 29%). The most common adverse effects were headache, fatigue, myalgia, and cough.

Conclusion: Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir treatment for 12 weeks was well tolerated by patients with HCV genotype 4 and resulted in 99% SVR for all patients who received 12 weeks of the study drugs. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02992457.

Keywords: HCV, treatment, Egypt, sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, Harvoni

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major public health problem with an estimated prevalence of over 184 million people worldwide.1 Patients with HCV are at risk of developing liver-related complications such as cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma.2

Egypt stands out as the country with the highest prevalence of HCV infection, recently estimated at 14.7% in subjects aged 15–59 years with a lower prevalence in urban areas (10.3%) compared with 18% in rural areas.3–5 In Egypt, 15% of an estimated population of 85 million are HCV positive, of whom >90% are infected with genotype 4 (GT 4).6,7 The rapid emergence of the epidemic in Egypt was initially fueled by the mass treatment of schistosomiasis using the injectable drug tartar emetic at some stage during the 1960s and 1970s.8

Optimal therapy for patients with HCV GT 4 infection is changing rapidly; for a long time, the standard of care has been a combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RBV), with modest response rates and considerable adverse events.9 The introduction of first-generation direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), was in 2011 with two new drugs (boceprevir and telaprevir). Later, in 2013, approval of the second-generation DAA, NS5B polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir (SOF), has been a further step forward due to its pan-genotypic effect on HCV with better pharmacokinetics and improved resistance profiles. With the advent of all oral DAA drugs with a broad range of genotypic activity and a low incidence of side effects, we are entering an exciting new era in the therapeutics of HCV.10

In October 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration approved a combination of SOF 400 mg with ledipasvir (LDV) 90 mg as a single pill (Harvoni). LDV is an NS5A replication inhibitor which is most active against genotype 1 (GT 1) and GT 4.11

The efficacy of SOF and LDV (Harvoni) was studied in a Phase III trial. In HCV GT 1 infection, the ION study and the LONESTAR trial showed the sustained virological response after 12 weeks (SVR12) rates of about 95%12,13 and 100%, respectively.11,14 However, the NIAID Synergy study, an open-label, single-center, Phase IIa trial of LDV/SOF treatment in HCV-4–infected patients, which recruited 21 patients showed an SVR12 rate of about 95%.15,16

Our aim was to assess the efficacy of combination treatment of SOF and LDV over a 12 week treatment period for HCV GT 4 patients in real life.

Patients and methods

This open-label, randomized trial was carried out on chronic HCV-infected patients attending four clinics: the El-Ebor clinic, Kafr-Elsheikh, Ain-Shams University, and Tanta University outpatient clinics during the period from October 2016 to April 2017. HCV infection was confirmed by positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for HCV infection (serum HCV RNA ≥12 IU/mL).

The duration of the study was 6 months starting immediately after obtaining approval from the Tanta University faculty of medicine ethical committee. An informed written consent was taken from each patient. All patients’ data were confidential with anonymized codes and were used for the current study only. Institutional ethical committee approval was obtained before the start of the study. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a prior approval by the institution’s human research committee.

Any unexpected risk appearing during the course of the research was made clear to the participants and ethical committee on time, and proper measures were taken to overcome or minimize these risks.

Complete blood count, liver function tests, fasting blood sugar, and serum creatinine were checked for all patients enrolled in the study. Moreover, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBs-Ag) test, α-fetoprotein, as well as abdominal ultrasonography were performed for all patients before starting treatment.

Two hundred treatment-naive patients who were HCV-antibody positive and HCV RNA positive by PCR, aged >18 years, were enrolled in the study and patients were randomized into two groups: Group I included 100 patients who received single therapy with SOF/LDV once daily for 12 weeks, while group II included 100 patients who received dual therapy with one SOF 400 mg tablet daily plus oral weight-based RBV (1000 mg/day for those weighing <75 kg or 1200 mg/day for those weighing ≥75 kg) for 24 weeks.

We decided to give the patients in group I SOF/LDV for 12 weeks based on previous data which concluded that SVR rates were significantly lower17 and relapse rates18,19 were higher in patients treated for 8 weeks compared with patients treated for 12 or 24 weeks, while other studies showed no significant difference regarding SVR when extending therapy for 24 weeks.12 On the other hand, reducing treatment duration decreases the rate of discontinuation of treatment and increases adherence.

Patients with a Child–Pugh score of ≥8, platelets <50,000, renal failure, previous history of hepatocellular carcinoma (except those 12 weeks after confirmed successful ablation of the malignant tumor), extrahepatic malignancies after a 2-year disease-free interval, and pregnant females were excluded, and all females of childbearing age and female partners of males who were enrolled in this study were advised to use contraceptive methods during and 6 months after treatment.

Follow-up of patients in both groups was performed every month during treatment when the patients attended the clinic to receive their monthly prescriptions. The patients were asked if they had experienced any side effects and were clinically evaluated. Complete blood count and liver and kidney function tests were performed every month. PCR for HCV was performed after 1, 3, and 6 months of treatment. End of treatment response was determined by quantitative PCR for HCV at the end of treatment for each of the study groups. The primary end point was an SVR12 after the end of treatment, as determined by quantitative PCR for HCV.

Efficacy assessment

Serum HCV RNA was measured using the Cobas Ampli Prep/Cobas TaqMan HCV-RNA assay (Roche Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA, USA) with a lower limit of detection of 15 IU/mL.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance between the studied groups was analyzed using unpaired t-test (for parametric variables), or chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test (for nonparametric variables). Statistical tests were performed with SPSS (Version 23). p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ demographic and baseline characteristics

There were no statistical differences between the studied groups regarding age, sex, serum alanine aminotransferase level, serum aspartate aminotransferase level, hemoglobin level, white blood cell count, platelet count, serum albumin level, serum bilirubin level, prothrombin time, α-fetoprotein level, serum creatinine level, fasting blood sugar level, and thyroid stimulating hormone level (Table 1).

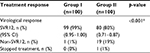

Treatment response in the studied groups after 12 weeks

Group I patients showed statistically significant higher SVR12 compared with group II patients (99% vs. 80% with 95% CI 0.95–1.00 vs. 0.71–0.87, respectively). Only one patient had to stop treatment in group II due to development of decompensation with ascites and jaundice (Table 2).

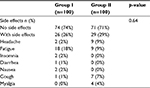

Side effects in the studied groups

There were no statistical differences between the studied groups regarding the frequencies of the side effects (Table 3).

| Table 3 Side effects in the studied groups |

Discussion

In this open-label, randomized trial, 200 previously untreated, HCV-infected patients were randomized into two groups and received treatment for HCV infection in the form of SOF/LDV for 12 weeks and SOF/RBV for 24 weeks, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference regarding demographic or laboratory investigations between the two studied groups. Some of these factors were previously associated with poor response to an interferon-based regimen.20,21

The sustained virological response was statistically significantly higher after 12 weeks (SVR12) in group I compared with group II. Our result was in accordance with that obtained by Afdhal et al12 who concluded that LDV–SOF with and without RBV for 12 or 24 weeks was highly effective for a broad range of treatment-naive patients with HCV GT 1 infection. Also, Kohli et al15 concluded that LDV and SOF treatment for 12 weeks was well tolerated by patients with HCV GT 4 and resulted in 100% SVR.

On the other hand, one patient in group I vs. 20 patients in group II did not achieve SVR, and one patient in group II had to stop therapy as the patient developed manifestations of hepatic decompensation in the form of ascites and jaundice.

There was no statistically significant difference between the two studied groups regarding side effects; fatigue was the most common side effect observed in group I, while headache, nausea, and insomnia were documented by patients to a lesser extent. This result was in agreement with the results of ION trials which concluded that fatigue, headache, nausea, and insomnia were the most common adverse effects recorded by patients.12,13,20 Also, Wyles et al22 documented that fatigue, headache, and diarrhea were the most experienced side effects. Headache, cough, and myalgia were more common in group II, which can be attributed to RBV.

This study adds value to the medical literature as there is little data published on SOF/LDV in GT 4 patients.

In conclusion, SOF–LDV is one of the best options for treatment of patients with HCV GT 4. This regimen is much better than SOF–RBV in this cohort of patients.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Wantuck JM, Ahmed A, Nguyen MH. Review article: the epidemiology and therapy of chronic hepatitis C genotypes 4, 5 and 6. Aliment Pharm Ther. 2014;39(2):137–147. | ||

Mc Combs J, Matsuda T, Tonnu-Mihara I, et al. The risk of long-term morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic hepatitis C: results from an analysis of data from a department of veterans affairs clinical registry. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):204–212. | ||

Guerra J, Garenne M, Mohamed MK, Fontanet A. HCV burden of infection in Egypt: results from a nationwide survey. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19(8):560–567. | ||

Elwan N, Elfert A, Abd-Elsalam S, et al. Study of hepatic steatosis index in patients with chronic HCV infection. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2016;5(5):266–274. | ||

Abd-Elsalam S, Sharaf-Eldin M, Soliman S, Elfert A, Badawi R, Ahmad YK. Efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treatment of cirrhotic patients with genotype 4 hepatitis C virus in real-life clinical practice. Arch Virol. 2017;163(1):51–56. | ||

AbdElrazek AE, Bilasy SE, Elbanna AE, Elsherif AE. Prior to the oral therapy, what do we know about HCV-4 in Egypt: a randomized survey of prevalence and risks using data mining computed analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93(28):e204. | ||

Ahmed OA, Kaisar HH, Hawash N, Samir H, et al. Efficacy of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin with or without peginterferon-alfa in treatment of a cohort of Egyptian patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2017;17(2):95–100. | ||

Lemoine M, Thursz M. Hepatitis C, a global issue: access to care and new therapeutic and preventive approaches in resource-constrained areas. Semin Liver Dis. 2014;34 (1):89–97. | ||

Abdel-Razek W, Waked I. Optimal therapy in genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C: finally cured? Liver Int. 2015;35(1):27–34. | ||

Cha A, Budovich A. Sofosbuvir: a new oral once-daily agent for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. P T. 2014;39(5):345–352. | ||

Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, et al. Sofosbuvir and Ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:515–523. | ||

Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P, et al. Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1889–1898. | ||

Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, et al. Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1483–1493. | ||

Gane EJ, Stedman CA, Hyland RH, et al. All-oral Sofosbuvir-based 12-weekregimens for the treatment of chronic HCV infection: the ELECTRON study. J Hepatol. 2013;58(1):S6–S7. | ||

Kohli A, Kapoor R, Sims Z, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 4: a proof- of- concept, single center, open-label phase 2a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(9):1049–1054. | ||

Smith MA, Mohammad R. Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 4 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(9):993–995. | ||

Backus LI, Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, Loomis TP, Mole LA. Real-world effectiveness of ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir in 4,365 treatment-naive, genotype 1 hepatitis c-infected patients. Hepatology. 2016;64(2):405–414. | ||

Wilder JM, Jeffers LJ, Ravendhran N, et al. Safety and efficacy of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir in black patients with hepatitis C virus infection: a retrospective analysis of phase 3 data. Hepatology. 2016;63:437–444. | ||

AASLD/IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2015;62:932–954. | ||

Davis GL, Lau JY. Factors predictive of a beneficial response to therapy of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1997;26(3):122S–127S. | ||

Kowdley KV, Gordon SC, Reddy KR, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 weeks for chronic HCV without cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2014:370(20):1879–1888. | ||

Wyles D, Pockros P, Morelli G, et al. Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus previously treated in clinical trials of sofosbuvir regimens. Hepatology. 2015;61(6):1793–1797. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.