Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Effects of Performance Pressure of Junior Faculty in Universities on Organizational Socialization: The Moderating Role of Organizational Support and Job Autonomy

Received 27 November 2022

Accepted for publication 28 February 2023

Published 15 March 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 841—856

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S399334

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Tianwei Ding,1 Ziru Qi,2 Jiaoping Yang2

1School of Business Administration, Liaoning Technical University, Huludao, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Economics and Management, Qingdao University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Ziru Qi, School of Economics and Management, Qingdao University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, 266000, Shandong, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Identification and recruitment of excellent junior faculty, and improving their organizational recognition and sense of belonging are the basis for sustainable development of high-quality colleges and universities. During the pre-employment period, the management of junior faculty in the by various colleges and universities focuses on screening, while organizational socialization tends to be ignored.

Materials and Methods: Based on the organizational identification theory, 438 new faculty members of colleges and universities were enrolled to investigate the effects of performance pressure on junior faculty by colleges and universities on their organizational socialization, as well as the dual regulation roles of perceived organizational support and job autonomy.

Results: Empirical analysis reveals that performance pressure has an inverted-U-shaped effect on organizational socialization of junior faculty members; the perceived organizational support negatively regulates the effects of performance pressure on organizational socialization; job autonomy regulates the effects of performance pressure on organizational socialization of junior faculty members by influencing organizational support of junior faculty members, indicating that job autonomy has secondary regulating effects on correlation of performance pressure with organizational socialization of junior faculty members.

Conclusion: This study elucidates the regulating effect of performance pressure on organizational socialization and explains the phenomenon that many junior faculty members in colleges and universities tend to avoid public affairs, do not integrate into the community and actively take responsibility for their work, which is of theoretical and practical value in the management of performance pressure among junior faculty members in colleges and universities.

Keywords: performance pressure on junior faculty, organizational socialization, perceived organizational support, job autonomy, organizational identification

Introduction

High-quality faculty is an important prerequisite for colleges and universities to maintain their core competitiveness, especially in the context of “Double First-Class” construction (It is a project implemented by China to improve the comprehensive strength of higher education, including first-class universities and first-class disciplines). In addition to research universities, several local colleges and universities have introduced various systems to attract outstanding talents and motivate faculty to increase research output. Unlike the management of employees in enterprises, the management of faculty in colleges and universities, especially in China, has many peculiarities such as, the long-established “identification management” and “unit people” approach which leads to an “easy to employ, hard to dismiss” phenomenon in faculty management.1 As a result, various colleges and universities in China have introduced the Western “up-or-out” system,2 with the aim of building an employee mobility mechanism.3 Practically, the “up-or-out” system can only can only eliminate newcomer or junior faculty, but has no incentive or restraint effects on career management of faculty passing the initial employment period.4 One of the negative impacts associated with the system is that colleges and universities have a high requirement for junior faculty to conduct research, especially young faculty, making them the target of pressure superposition.5 Recently, several issues associated with the “up-or-out” system have aroused widespread concern and triggered a great debate on the rationality of this system.6 In this study, the misuse and disadvantages of this system are not analyzed.7 Instead, we explore how to design the performance assessment criteria for junior faculty from the perspective of colleges and universities to ensure that more talented people are recruited, retained, and kept for a long time, so as to enhance the competitive advantages of colleges and universities.

New employees are the new driving forces of organizational development. For colleges and universities, sustainable and high-quality development largely depends on recruitment of junior faculty who have outstanding abilities, identify with and integrate into the college or university, and are willing to teach in the college or university for a long time. Therefore, management of junior faculty in their initial employment period should take into account the screening of excellent faculty and promote their integration into the community, ensuring their willingness to stay in the college or university. From a human resource management perspective, the process by which new employees change their attitudes and behaviors to match the organization’s development goals, value systems, or behavioral norms, and transform themselves from outsiders to insiders, is called organizational socialization.8 The organizational socialization process is critical for the entry of junior faculty into colleges and universities, which affects their future performance and influences the development of colleges and universities.9,10 Successful organizational socialization play an important role in the development of sense of identity and belonging among junior faculty which is beneficial to colleges and universities in retaining faculty members. When it comes to performance management of junior faculty members during their initial employment period, existing colleges and universities put excess focus on the ability of junior faculty members to achieve research results but ignore their ability or desire to integrate into the community and continue to serve the collective goal of the community. The “up-or-out” system leads to low recognition of junior faculty by colleges and universities.3 It is understandable that those who do not pass the assessment get to leave, but a lack of sense of belonging can also be seen in those who stay, which is reflected in the fact that they either go slack in work or look for opportunities to jump to other colleges and universities after the initial employment period.11 Performance pressure has double-edged sword effects on employee behavior or performance.12 Rational performance pressure can motivate junior faculty to actively seek guidance and help from other colleagues, actively participate in internal activities of colleges and universities, actively integrate into the organization, and achieve organizational socialization. However, excessive pressure makes junior faculty members focus more on research tasks, which reduces their participation in group activities, public affairs of the organization,11 with minimal assistance from forces outside the organization, which is not conducive to their integration into the community as well as organizational socialization. Therefore, on the premise of recognizing the implementation of assessment for junior faculty at the initial employment period, this study investigated which level of performance pressure is conducive for organizational socialization of junior faculty.

According to the organizational identification theory, new employees want to be accepted and recognized by internal members of the organization.13 Thus, organizational support perceived by new employees can create a good working environment, promote communication among employees, and reduce the tendency of new employees to leave the organization.14 For junior faculty, a high perceived organizational support from college/university or the school indicates a strong will to empower them, therefore, junior faculty members will be motivated to actively participate in relevant research groups and cooperate with other colleagues even if they face high pressure, which will help them achieve their performance objectives and accelerate their organizational socialization process. However, if colleges and universities have very low support structures for junior faculty, junior faculty members in the case of high pressure can only complete their assessment tasks by staying away from their colleagues or the group, making it unlikely to develop a sense of collective identity. Many famous colleges and universities have adopted a personnel system that is similar to the “up-or-out” system. Many junior faculty members can quickly integrate into the organization during the pre-employment period and are willing to stay in the college or university after passing the assessment during the pre-employment period. A college or a university is a good platform for empowering the career development of faculty members. Additionally, academic research is a creative activity that requires a relatively relaxed and autonomous environment. Job autonomy can regulate the effects of organizational support on the result.15 Therefore, if junior faculty members face restrictions at work that render them unable to work autonomously, their organizational socialization processes will be affected even in the presence of high perceived organizational support. Instead, if colleges and universities can provide a relaxed, autonomous research environment for junior faculty and support them, some level of performance pressure may make them more willing to integrate into the group and improve their working efficiency. Hence, with perceived organizational support and job autonomy as boundary conditions, this study explored the moderating mechanisms of perceived organizational support on the correlation between performance pressure with organizational socialization as well as the regulating effects of job autonomy on perceived organizational support.

In this study, based on organizational identification theory, newly recruited faculty members in various colleges and universities were recruited to investigate how performance pressure influences the organizational socialization of junior faculty members as well as the dual regulating roles of perceived organizational support and job autonomy.4,11,15 This study has the following two potential contributions: first, it enriches the studies on performance pressure among faculty members in colleges and universities, relates performance pressure with organizational socialization of junior faculty, and elucidates on the effects of performance pressure; second, with perceived organizational support and job autonomy as regulating variables, it clarifies the boundary conditions of performance pressure influencing organizational socialization of junior faculty members and provides a reference for decision-making in management of new employees in colleges and universities or other organizations.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Performance Pressure and Organizational Socialization

Performance pressure refers to negative emotional responses of individuals who are concerned that their current performance is insufficient to meet expected goals.16 The results of existing studies on performance pressure are mainly from two dimensions. First, in terms of performance pressure levels, some studies have suggested that performance pressure may easily make employees “hard to breathe under pressure”, which is not conducive for employee development;17 while other studies have concluded that high pressure is conducive for employee and organization development.18 Second, characteristically, performance pressure is divided into two categories, that is, demotivating pressure and motivating pressure. Demotivating pressure has dominating negative effects, which is often detrimental to both individual employee development and organizational performance, while motivating pressure has a dominating positive effect, which tends to stimulate employee creativity and strengthen the sense of collective identity.19,20 Performance pressure among new employees has been widely studied, however, majority of the studies have focused on the relationship between performance pressure and employee well-being, physical and mental health, and employee performance.21 There are some theoretical gaps in research on performance pressure and organizational socialization. With competitive pursuit of research achievements in colleges and universities, high expectations are placed on junior faculty members, therefore, there is a need to establish appropriate mechanisms to make junior faculty members quickly integrate into the school environment to achieve organizational socialization.

The organizational socialization concept was first introduced into the organizational behavior field by Schein22 to represent the processes by which new employees grow from outsiders to insiders by performing appropriate duties, completing role tasks, and gaining organizational identification. Organizational socialization has a crucial role in helping new employees adapt to their environment and improve their behavioral performance.8 Most of the previous studies on organizational socialization recruited new enterprise employees as study participants and majorly focused on the effects of organizational environment on organizational socialization of new employees,23 the effects of features of new employees on organizational socialization,24 and the impact of organizational socialization on individuals or organizations.8 Due to high mobility of enterprise employees and the high autonomy of employees in job selection, a limited number of studies have paid attention to effects of performance pressure on organizational socialization. Besides enterprise employees, junior faculty members in colleges and universities are also faced with organizational socialization challenges, and due to particularity of the profession, in the context of “up-or-out” system in many colleges and universities, the effects of performance pressures on organizational socialization of junior faculty members in colleges and universities has become more prominent and special.25 Based on practical observations and previous studies, we postulated that performance pressure has an inverted U-shaped nonlinear effect on organizational socialization processes of junior faculty members.

When junior faculty members in colleges and universities have low performance pressure, their internal driving force to achieve performance objectives will be hindered, which is not conducive for the organizational socialization process. First, when junior faculty members have low performance pressure, they can accomplish their work tasks with little time and effort, therefore, their energy, time, and emotional investment in their own work and organizational affairs will be low, which will slow down their adaptation processes to the new environment.24 This makes it hard for them to integrate into the organization and develop a sense of belonging. Second, a lack of performance pressure not only makes it difficult to recognize one’s identity and understand job characteristics but also leads to a lack of a sense of self-fulfillment and internal driving force, sapping the motivation to innovate and inhibiting innovative thinking,19 thereby suppressing the organizational socialization process. In cases of low performance tasks that can be easily achieved, faculty members in colleges and universities tend to accomplish them alone rather than seek cooperation with others. The ability of an individual to quickly integrate into an organization depends on his or her communication skills and cooperation with colleagues.10 Therefore, low performance pressure inhibits the development of interpersonal relations among new faculty members in colleges and universities and is not conducive for the organizational socialization process.

According to the organizational identification theory, maintaining a rational performance pressure is beneficial for junior faculty members to perceive the overlap between their roles and organizational identity characteristics, leading to organizational identification.13 For new faculty members in colleges and universities, as performance pressure increases and can be overcome, the organizational socialization process tends to accelerate. Besides, research performance tasks represent expectations of colleges and universities on junior faculty, and performance pressure is aimed at achieving excellence and motivating individuals to strive for better performance to achieve desirable results.26 Within a controllable range, performance pressure can encourage faculty members to work together with colleagues and peers to accomplish their performance objectives, building a good interpersonal environment and making them less uncertain about the new environment and work, thereby accelerating their integration into the organization and the organizational socialization process. Moreover, rational performance pressure enhances the realization of self-actualization by junior faculty members. When they meet or exceed their performance objectives, the performance pressure on them will be transformed into a sense of accomplishment, promoting individual growth. From a social exchange perspective, when junior faculty members have a sense of self-fulfillment, their recognition of organization is enhanced,27 which helps them find their position in the organization and eventually show their sense of loyalty and belonging to the organization, thereby successfully completing the organizational socialization process.

However, over-high pressure may inhibit the organizational socialization process of faculty members of colleges and universities. First, excess workload and research pressure will increase the physical and mental burden of faculty members and worsen their anxiety. Anxious faculty members will focus all their energy on performance tasks and deviate from their expectations of their roles by only caring for their own interests.28 As a result, they have no energy to consider how to adapt to the environment and integrate into the organization, and even generate negative emotions, which inhibits the process of integrating them into the new organization. When performance pressure exceeds a certain threshold, the sense of psychological safety and free time among faculty members becomes threatened. According to the organizational identification theory, when faculty members believe that the organization has harmed their interests, they will feel dissatisfied and retaliatory towards the organization;29 Besides, over-high pressure reduces the psychological expectations and trust of junior faculty members in the organization and negatively affects their sense of organizational identification,29 resulting in their refusal to integrate into the organization. Additionally, uncontrollable performance pressure enhances the chances for job burnout among faculty members in the face of work tasks with “quantity matters more than quality”, thereby lacking sufficient energy and interests to familiarize themselves with their surroundings and form cooperative relationships with colleagues.5

Based on above analyses, we postulated that the relationship between performance pressure on faculty members in colleges as well as universities and organizational socialization is not a simple linear relationship. When performance pressure on faculty members of colleges and universities is below a certain level, it has a positive effect on the organizational socialization process, but when performance pressure exceeds a certain level, the positive effects of performance pressure on organizational socialization will be weakened or become negative. Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H1: Performance pressure on junior faculty members of colleges and universities has an inverted U-shaped correlation with organizational socialization.

Regulatory Effects of Perceived Organizational Support

Perceived organizational support is an employee’s overall perception of the existence of emotional acceptance and material support in an organization.30 Psychological support and other forms of support by an organization can provide employees with good work experience and make them feel cared for and valued by an organization.14 As a subjective factor, perceived organizational support can influence employees’ attitudes and behaviors towards their work.31 High perceived organizational support can enhance employees’ sense of belonging to the organization,23 encourage employees to work more actively, and improve their work performance.32 Perceived organizational support can also strengthen employees’ organizational identification and make them feel that they and the organization are a community with a shared future, thereby promoting the organizational socialization process of new employees.8 Faculty members of colleges and universities are knowledge workers, and perceived organizational support can increase their job satisfaction33 and promote knowledge sharing.34 According to the organizational identification theory, at the early stage of new employee entry into an organization, the success of organizational socialization is determined by their sense of organizational identification,23 and perceived organizational support can effectively enhance organization recognition by new employees. On this basis, we postulated that high perceived organizational support can strengthen the positive effects of performance pressure on organizational socialization of junior faculty.

For new faculty, if the college or university has rich research resources, a good research platform, and a good interpersonal atmosphere, ie, if they perceive high organizational support from the college or university for their work, they will attempt to integrate individual and organizational resources to complete their work to demonstrate their value and gain organizational recognition, as long as it is within their tolerance. In this process, they achieve identity assimilation.10 Thus, high perceived organizational support will make employees feel emotionally supported and replenished with resources, reducing the negative effects of pressure and transforming them into a form of challenging pressure,32 thereby accelerating organizational identification and helping new employees achieve organizational socialization.

However, if junior faculty perceive that it is difficult to obtain research resources at the school and that they have to work alone in research, ie, if junior faculty perceive little or no organizational support from their school, even if performance pressure is not very high, they will be reluctant to devote time and energy to organizational matters unrelated to their work tasks but choose to avoid organizational interruptions or even to cooperate with people outside the organization to complete their tasks as soon as possible.11 If junior faculty perceive that performance pressure is more than they can bear, they will tend to work alone since they cannot feel the help and support from the organization, which will lead to job burnout and avoidance of work and life,11 resulting in their inability to integrate into the organization.

For college and university faculty, publication of scientific research papers and obtaining project funding is a competition among faculty members, and competition among faculty is not only a competition of individual ability but also a competition of resources and platforms among their colleges and universities.5 In practice, performance pressure on junior faculty members and all faculty is relatively high in colleges and universities with a strong comprehensive strength, which is because the resources and platforms of these colleges and universities can help faculty tackle relatively high pressure-related jobs, in addition to strong personal abilities of recruited faculty members. Faculty members of colleges and universities with strong comprehensive strengths have a relatively low voluntary turnover rate. The reason is that, although colleges and universities with strong comprehensive strength have high pressure, because of the high perceived organizational support, the faculty members still have a relatively high identification with them. On this basis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Perceived organizational support regulates the correlations between performance pressure with organizational socialization of junior faculty members. The higher the perceived organizational support, the stronger the positive effects of performance pressure on organizational socialization of junior faculty members, and the lower the perceived organizational support, the stronger the negative effects of performance pressure on organizational socialization of new employees.

Secondary Regulation of Job Autonomy

As one of the core work characteristics, job autonomy refers to the extent to which employees can control and decide their own work modes, arrangement, and standards.35 Job autonomy reflects the extent to which an organization values the employees’ input and recognizes their contribution to the organization.36 Moreover, employees can perceive their personal responsibility to the organization,35 which is conducive for innovative thinking and problem solving.37 Job autonomy can influence employee attitudes to change their behaviors. For instance, job autonomy can increase job38 and life39 satisfaction thereby reducing employee turnover.12 For faculty members of colleges and universities who are knowledgeable workers, job autonomy can reduce knowledge hiding behaviors and accelerate knowledge exchange as well as dissemination among organizations.

Faculty members of colleges and universities are a group of persons who pursue academic freedom and job autonomy.11 If colleges and universities give junior faculty members enough freedom in their work modes and arrangement, it implies the expectation and confidence of colleges and universities in their performance. The faculty is more likely to develop organization recognition and a sense of belonging,35 shorten their “psychological distance” with the organization, and perceive organizational support. According to the organizational identification theory, when proactive employees develop organizational identification, they see themselves as members of the organization and are therefore more likely to feel support from the organization at psychological and resource levels. Therefore, regulatory effects of perceived organizational support on the correlation of performance pressure with organizational socialization may be influenced by job autonomy.

The faculty with high job autonomy can work at their will and make full use of their personal strengths, which reflects the organization’s recognition and trust in their abilities and make them feel valued and expected by the organization. Meanwhile, junior faculty members can reasonably and flexibly use various organizational resources provided by colleges and universities,15 further enriching the situational factors of the faculty’s perceived organizational support. In this case, the larger the perceived organizational support, the greater its effects, and the stronger its regulatory effect on the correlation between performance pressure with organizational socialization of junior faculty. However, if faculty members of colleges and universities have a low job autonomy, it indicates that the faculty are restricted in many ways at work and lack the coordination of relevant resources as well as authority, which reflects the lack of trust in the faculty by the organization. Therefore, the psychological states of faculty members will be affected while their organization recognition will be reduced,35 making them feel insufficient concerning perceived organizational support. In this case, the smaller the perceived organizational support, the lower its effect, and the weaker its regulatory effects on performance pressure and organizational socialization of junior faculty members.

Concerning research, faculty members should focus their research in terms of experimentation or innovation. For this reason, job autonomy is an important parameter. Since colleges and universities with strong comprehensive strengths have a strong talent base, they will not put too much teaching pressure or assign many public affairs to junior faculty, thus, junior faculty members have high job autonomy, which makes them more likely to get organizational support. However, in colleges and universities with weak comprehensive strengths, the faculty-student ratio is low. In this case, junior faculty members are often forced to take on more performance assessment tasks, and in the face of performance pressure, junior faculty members will only tend to avoid their leaders or colleagues, which is not conducive to obtaining organizational support. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Job autonomy moderates the regulatory effects of perceived organizational support on the correlation between performance pressure and organizational socialization of junior faculty members. It is represented by a moderated regulatory model, that is, the higher the job autonomy, the stronger the regulatory effects of perceived organizational support on the correlation between performance pressure with organizational socialization of junior faculty members.

Based on the above hypotheses, a theoretical model was established (Figure 1). First, the model suggests that there exists a rational range of performance pressure on junior faculty members in colleges and universities. Performance pressure beyond this range is not conducive to integration of junior faculty members into the community. In other words, if colleges and universities in the “up-or-out” system put excessive pressure on junior faculty members, even if they recruit and select excellent faculty members, excellent faculty members may exhibit a poor sense of belonging to colleges and universities or may even leave, that is, too much is as bad as too little. Colleges and universities should exert pressure on junior faculty members by considering their average research, the platform supports that the colleges and universities can give to the faculty to achieve their performance objectives shall also be considered. It means that colleges and universities with abundant research resources and strong discipline strengths can put relatively higher performance pressure on new employees, while colleges and universities with scarce research resources and weak discipline strength shall appropriately reduce the performance pressure on junior faculty members, that is, colleges and universities shall act according to their abilities. Additionally, performance pressure on junior faculty members is often about research performance, in which case, a relaxed atmosphere and discretionary perspective are required to give the school’s policy and resource support. If junior faculty are involved in heavy public affairs and lack job autonomy, they cannot perceive organizational support and develop a sense of organizational deprivation, which increases the negative effects of performance pressure.

|

Figure 1 Theoretical model (perceived organizational support, job autonomy, performance pressure of new faculty, organizational socialization). |

Research Design

Participants and Procedures

This study involved young faculty members who had been employed in colleges and universities within the past 5 years to engage in research and teaching. Study participants were enrolled from 12 colleges and universities in Qingdao, Jinan, and Tianjin. Before the formal survey, 150 questionnaires were distributed to 10 randomly selected schools. A total of 134 questionnaires were responded to, with a validity rate of 89.33%. Based on the feedback, the questionnaires were modified to generate a formal questionnaire. The formal survey started in March 2022 and lasted until June 2022. Data were collected in the following three patterns; (1) Written or online questionnaires were distributed through platforms such as professional academic conferences and large academic meetings; (2) Questionnaires were collected by making full use of the faculty’s social networks. We contacted the relevant faculty members, obtained their consent, distributed electronic questionnaires via email and WeChat, informed them of the survey, and collected the questionnaires in the same way; (3) After contacting local colleges and universities through emails and phone calls, we distributed and collected the questionnaires on-site. To ensure data authenticity and reliability, we carefully communicated with respondents before the survey, informed them of data confidentiality as well as the importance and academic nature of the survey. Respondents were induced to participate in this study by giving them souvenir gifts. In the formal survey, 491 questionnaires were collected. After elimination of invalid questionnaires with obvious regular responses and incomplete information, a total of 438 questionnaires were established to be valid, with a validity rate of 89.21%. The descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Samples |

Measures

As shown in Table 2, The proposed model involves performance pressure, perceived organizational support, job autonomy, and organizational socialization. To ensure the reliability and validity of measurement tools, maturity scales were used, and all English scales were accurately translated and back-translated. Since this paper is centered on faculty members of colleges and universities, some items were adjusted (eg, “colleague”, “unit”, and “supervisor” were changed to “faculty”, “school”, and “leader”) to ensure the accuracy and local contextual applicability of scales.

|

Table 2 Latent Variable Scale and Its Reliability and Validity |

Control variables: Based on previous studies, gender (C1), age (C2), country where the graduated college or university is located (C3), graduated college or university (C4), and mentor title (C5) were taken as control variables. C3, C4, as well asC5were dummy variables and C3 with a value of 1 indicated graduation from a college or university in China, C4with a value of 1 indicated a Double First-Class college or university, C5with a value of 1 indicated that the mentor is an academician or a “Changjiang Scholar”.

Research Tools

Analysis of the data using SPSS25.0 and Mplus 7.0 entailed the following steps: (1) SPPS was used to perform descriptive statistical analysis, correlation analysis, internal consistency analysis and regression analysis; (2) Mplus was used to perform confirmatory factor analysis of the data to examine the reliability and validity of the scale.

Results

Common Method Bias Test

The unrotated exploratory factor analysis of all items of the study variables found that the cumulative variance interpretation rate of factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 was 72.61%. The interpretation rate of the factor with the largest eigenvalue was 24.26%, which was less than half of the cumulative interpretation rate, indicating that the homogeneous bias problem was not serious.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Internal consistency analysis showed that Cronbach, s α coefficients for performance pressure, perceived organizational support, job autonomy, and organizational socialization were all greater than the standard minimum of 0.7, while the CITC values were all > 0.4, indicating that all four scales had good reliability. Next, validity analysis was conducted. Mplus7.4 was used for exploratory factor analysis. In Table 3, the four-factor model fit best to the sample data (χ2/df =1.494, RMSEA=0.034, SRMR = 0.046, CFI =0.977, TLI =0.974), which was significantly better than the other three three-factor models, while the single-factor model fit the worst (χ2/df =8.322, RMSEA =0.129, SRMR =0.145, CFI =0.654, TLI =0.620), indicating that the four variables in this study have a good discriminant validity.

|

Table 3 Comparisons of Model Validation Factor Analysis |

Correlation Test

Findings from correlation analyses of variables are shown in Table 4. Performance pressure and organizational socialization were significantly negatively correlated (r=−0.227, p<0.01), while existence of a non-linear relationship between the two should be further analyzed by regression tests. Organizational socialization and perceived organizational support (r=0.215, p<0.01) and organizational socialization and job autonomy (r=0.277, p<0.01) were positively correlated, consistent with our postulate and can provide preliminary support for hypothesis testing.

|

Table 4 Variable Correlation AnalysisResults |

Hypothesis Testing

Main Effect Test

Direct effects were tested by performing hierarchical regression in SPSS25.0. In Table 5, performance pressure on junior faculty members was taken as the independent variable while organizational socialization was the dependent variable for regression analysis. Hypothesis 1 proposed that performance pressure has an inverted-U-shaped effect on organizational socialization of junior faculty. This hypothesis was tested by following the previous testing procedures of curve effects. Model 2 revealed that performance pressure has a significant negative effect on organizational socialization of junior faculty members (r=−0.117, p<0.01). However, Model 3 showed a significant negative relationship between the squared term of performance pressure and organizational socialization (r=−0.260, p<0.01). Besides, compared to Model 2, the variation in Model 3 was significant (ΔR2=0.139, p<0.01), indicating that Model 3 can better reflect the correlation between performance pressure and organizational socialization of junior faculty members. Therefore, performance pressure has an inverted-U-shaped correlation with organizational socialization of junior faculty members, which serves as data support for Hypothesis 1. Based on collected questionnaire data and Model 3, we can obtain the optimal performance pressure PP*=2.742. In Table 4, the average performance pressure is 2.945>2.742, indicating that the average performance pressure in the sample data is high, that is, most of the junior faculty members in colleges and universities feel that performance pressure is too high.

|

Table 5 Regression Analysis Results |

Verification of Regulating Effect

Hypothesis 2 proposed that the perceived organizational support can regulate the inverted-U-shaped correlation of performance pressure with organizational socialization of junior faculty members. To verify the hypothesis, perceived organizational support and the interaction term between perceived organizational support and performance pressure were added into Model 2 for regression analysis. Model 4 revealed that the interaction term between the squared value of performance pressure and perceived organizational support is positively correlated with organizational socialization (r=0.133, p<0.01). At this point, compared to Model 2, the variation of R2was significant (ΔR2=0.070, p<0.01), which verifies Hypothesis 2. To explain the regulating effects of perceived organizational support, Model 4 revealed that the optimal performance pressure PP*=2.782+3.262/(666.496–133PP), implying that with increasing PP, optimal performance pressure will gradually increase.

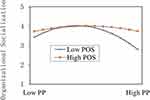

To give a clearer presentation of the regulating effect of perceived organizational support on the association of performance pressure with organizational socialization of junior faculty members, the regulating effect of perceived organizational support was plotted (Figure 2). When the perceived organizational support is high, the positive effects of performance pressure on organizational socialization of junior faculty members are enhanced, while the negative effects are weakened; when the perceived organizational support is low, the negative effects of performance pressure on organizational socialization of junior faculty members are enhanced, while the positive effects are weakened.

|

Figure 2 Regulating effect of POS. |

Verification of Secondary Regulating Effect

In Model 5, interaction terms of job autonomy, perceived organizational support, and performance pressure (including interaction terms between any two of the three variables) were introduced. The interaction terms of job autonomy, perceived organizational support and performance pressure were significantly positively correlated with organizational socialization of junior faculty members (r=0.078, p<0.05), and the interaction terms of job autonomy, perceived organizational support and the squared value of performance pressure were significantly positively correlated with organizational socialization (r=0.123, p<0.01). Besides, compared to Model 4, the variation of R2 is significant (ΔR2=0.069, p<0.01), which verifies Hypothesis 3. According to Model 5, optimal performance pressure can be calculated by:

PP*=2.783+(0.012POS×JA-0.002POS)/(0.279–0.165POS-0.123POS×JA).

Then, it can be easily obtained that ∂PP*/∂POS increases with increasing JA.

Figure 3 shows the regulating effects of job autonomy on perceived organizational support and the correlation between performance pressure and organizational socialization of junior faculty members. With increasing job autonomy, the positive regulating effect of perceived organizational support on correlation of performance pressure with organizational socialization of junior faculty members is enhanced. That is, job autonomy regulates the perceived organizational support and thus has a positive regulating effect on the correlation between performance pressure with organizational socialization of junior faculty members.

|

Figure 3 Regulating effect of JA and POS. |

Discussion

Theoretical Contribution

This study elucidates the regulating effect of performance pressure on organizational socialization and explains the phenomenon that many junior faculty members in colleges and universities tend to avoid public affairs, do not integrate into the community and actively take responsibility for their work, which is of theoretical and practical value in the management of performance pressure among junior faculty members in colleges and universities.

First, the mechanism via which performance pressure influences organizational socialization was studied, which explains the effects of performance pressure on new employees and promotes the organizational socialization of junior faculty members in colleges and universities. Most of the existing studies assessed the mechanism via which performance pressure influences employee performance and innovative behaviors,20,24 and few studies associated employee performance pressure with organizational socialization. Due to the significance of organizational socialization in future development of employees and organizations, there is a need for theoretical and practical evaluation of the relationship between the two. Since colleges and universities have different human resource management methods compared with enterprises, performance management of new employees in colleges and universities has its own particular characteristics. In the context of the existing “up-or-out” and “pre-employment long appointment” system, we investigated the impacts of performance pressure on organizational socialization of new employees, which is of great significance for sustainable management of new employees in colleges and universities. We found that the effect of junior faculty members’ performance pressure on organizational socialization was not simply positive or negative but showed an inverted-U-shaped trend. This finding verifies the idea that performance pressure has a “double-edged sword” effect,12 which enriches the knowledge on the effects of performance pressure and provides important theoretical guidance for management of new employees in colleges and universities and other organizations.

With perceived organizational support as the regulating variable, we investigated the boundary conditions via which the mechanisms of performance pressure influences organizational socialization, which can help in understanding the effects of performance pressure from the perspective of contingency management. Most of the previous studies were conducted from the perspectives of employee self-efficacy and leadership behaviors19 to investigate the boundary conditions of the effects of performance pressure. Compared to these studies, this study revealed the regulating effects of perceived organizational support from the perspective of organizational behaviors. Based on the organizational identification theory, we suggested that when the organizational support perceived by junior faculty is high, the positive effect of performance pressure on organizational socialization will be strengthened, while the negative effect of performance pressure on organizational socialization will be weakened, and vice versa. This study verified the conclusion that40 perceived organizational support can help reduce work pressure and increase job satisfaction and answered the question on why some colleges and universities have been successful in adopting the “up-or-out” system while other colleges and universities have attracted a lot of criticism and even brought negative impacts4 Therefore, this study elucidates on the correlation between performance pressure with organizational socialization.

Additionally, we explored the effects of job autonomy on the correlation between performance pressure with organizational socialization of junior faculty members and highlighted the work characteristics of the faculty of colleges and universities. Our findings provide an important theoretical basis for performance management of employees in colleges and universities. Job autonomy has a regulating effect on organizational citizenship behaviors and task performance,41 that is, job autonomy can increase job satisfaction38 as well as reduce knowledge hiding behaviors,42 and high job autonomy can help achieve more reasonable and flexible organizational resource usage.15 However, studies have yet to integrate performance pressure, perceived organizational support, and job autonomy. Using job autonomy as the secondary regulating variable of the correlation between performance pressure and organizational socialization of junior faculty members, it was found that when job autonomy is high, perceived organizational support is more conducive for postponing the negative effects of performance pressure on organizational socialization. This conclusion revealed the complexity of the effects of performance pressure on organizational socialization, deepened the understanding of studies on job autonomy, and provided some ideas for further research.

Management Enlightenment

Due to the rigidity of the faculty system of colleges and universities, in the context of the increasingly fierce competition among colleges and universities, they have adopted a method of applying the new system for new employees but continuing to use the old system for existing employees. Adopting the “up-or-out” system for new faculty members can ensure the recruitment of outstanding faculty on one hand and distributes the competitive pressure of schools on junior faculty on the other hand. In this case, junior faculty members will feel the gradual increase in performance pressure. From the perspective of organizational socialization, we found that the existing performance pressure on junior faculty is too much, and colleges and universities should put a reasonable amount of performance pressure on new employees based on their employer brand, resources, as well as capabilities, and mechanical imitation of others shall be avoided. Based on our findings, the following management recommendations are given:

Firstly, management personnel shall control the performance pressure on junior faculty members at a certain level. A certain level of performance pressure can help in effective identification faculty’s comprehensive abilities and help them to quickly integrate and identify with the group. However, too much performance pressure makes junior faculty members to tend to stay away from the organization in accomplishing their tasks, thus hindering organizational socialization, and in this case, even if excellent faculty are selected, they may not be willing to work for the organization. Therefore, management personnel in colleges and universities shall set appropriate targets according to average abilities of junior faculty and assign performance tasks that can be achieved by excellent faculty members through their efforts, to promote organizational socialization of junior faculty members.

Secondly, colleges and universities should consider the resources and platforms provided by schools, colleges, and departments when setting performance tasks for junior faculty and actively provide assistance as well as support to junior faculty members in the process of completing their tasks, so as to enhance the perceived organizational support of junior faculty members. In terms of feasibility of performance tasks, colleges and universities with rich research resources and strong research abilities can appropriately increase the performance tasks of junior faculty members in certain colleges and departments. In view of organizational socialization of junior faculty members, management personnel shall pay special attention to caring for junior faculty members, thereby increasing policy and resource support, valuing their needs in life and work, and helping them accomplish performance tasks, thus making faculty get high perceived organizational support.

Additionally, job autonomy of junior faculty members shall be increased to a certain extent to build a relaxed environment for junior faculty members. The management of colleges and universities should be aware that research requires a relaxed and flexible working environment, and thus junior faculty members require high autonomy to prevent work overload among them. This will enhance the sense of organizational identification and the sense of belonging for junior faculty, thereby reduce the explicit and implicit turnover rate.

Research Limitations and Perspectives

Although the hypothesis proposed in the article has been confirmed, there are still improvements, mainly in: First, the data obtained in this study are mainly cross-sectional data, which is difficult to reflect the dynamic causal relationship between performance pressure and organizational socialization. Future research can diversify data sources, and use tracking research design to make the data reflect changes in a certain period of time, so as to make the causal relationship between relevant variables more convincing. Second, this study takes organizational support as a moderator variable, which is relatively not specific. In the future, we can combine the AMO model to explore the moderator functions of empowerment, authorization and incentive, and increase the relevant mediating variables to systematically analyze the contingency impact of performance pressure on organizational socialization.

Conclusion

Based on organizational identification theory, this study investigated the effects of performance pressure on organizational socialization of junior faculty members, it was established that: (1) Performance pressure has an inverted-U-shaped effect on organizational socialization, that is, too high or too low performance pressure is not beneficial for organizational socialization of junior faculty members; (2) Perceived organizational support has a regulating effect on correlation of performance pressure with organizational socialization of junior faculty members, and perceived organizational support can alleviate the negative effects of performance pressure on organizational socialization and increase the optimal performance pressure of junior faculty members; (3) Job autonomy can affect the impacts of performance pressure on organizational socialization of junior faculty members by affecting their perceived organizational support, that is, job autonomy has a secondary regulating effect on the correlation between performance pressure with organizational socialization of junior faculty members.

Data Sharing Statement

Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical Considerations

The protocol was approved by an institutional review board of Liaoning Technical University of China. All subjects read informed consent before participating this study and voluntarily made their decision to complete surveys.

Declaration of Helsinki

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2022MG041), Key R&D Projects in Shandong Province (2021RKY01016) and Important Projects of The National Social Science Foundation in China (21AZD120). With the cooperation of Qi Ziru, Yang Jiaoping, this paper has got the convincing survey data and reach the current solution.

Disclosure

The authors declare no competing interests in this work.

References

1. Wang S, Jones GA. Competing institutional logics of academic personnel system reforms in leading Chinese Universities. J Higher Educ Policy Manage. 2021;43(1):49–66. doi:10.1080/1360080X.2020.1747958

2. Barbulescu R, Jonczyk C, Galunic C, et al. Management of fortuity: workplace chance events and the career projections of up-or-out professionals. J Vocat Behav. 2022;139:103791.

3. MacLeod WB, Urquiola M. Why does the United States have the best research universities? Incentives, resources, and virtuous circles. J Eco Perspectives. 2021;35(1):185–206.

4. Zhu YC. Risk judgment and cracking path of “pre-employment long appointment” system reform in universities. Teacher Educ Res. 2021;33(1):40–44.

5. Johnson AP, Lester RJ. Mental health in academia: hacks for cultivating and sustaining wellbeing. Am J Human Biol. 2022;34:e23664.

6. Liu J, Wang H. What is the real “up-or-out”. Chongqing Higher Educ Res. 2020;8(5):44–54.

7. Liu XD. Analysis on the dilemma and improvement path of “up or out” in colleges and universities in China: based on the revised content of teachers’ law (draft for comments). Res Educ Dev. 2022;42(5):53–60.

8. Woodrow C, Guest DE. Pathways through organizational socialization: a longitudinal qualitative study based on the psychological contract. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2020;93(1):110–133.

9. Nifadkar SS, Bauer TN. Breach of belongingness: newcomer relationship conflict, information, and task-related outcomes during organizational socialization. J Appl Psychol. 2016;101(1):1–13.

10. Deng Y, Yao X. Person-environment fit and proactive socialization: reciprocal relationships in an academic environment. J Vocat Behav. 2020;120:103446.

11. Zhao X, Yin H, Fang C, et al. For the Sustainable Development of Universities: exploring the External Factors Impacting Returned Early Career Academic’s Research Performance in China. Sustainability. 2021;13(3):1–20.

12. Liu F, Li P, Taris TW, et al. Creative performance pressure as a double-edged sword for creativity: the role of appraisals and resources. Hum Resour Manage. 2022;61(6):663–679.

13. Ravasi D, Rindova V, Stigliani I. The stuff of legend: history, memory, and the temporality of organizational identity construction. Acad Management Jo. 2019;62(5):1523–1555.

14. Rhoades L, Eisenberger R. Perceived organizational support: a review of the literature. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(4):698–714.

15. Meyers MC, Adams BG, Sekaja L, et al. Perceived organizational support for the use of employees’ strengths and employee well-being: a cross-country comparison. J Happiness Stud. 2019;20:1825–1841.

16. Eisenberger R, Aselage J. Incremental effects of reward on experienced performance pressure: positive outcomes for intrinsic interest and creativity. J Organ Behav. 2009;30(1):95–117.

17. Gimmig D, Huguet P, Caverni JP, et al. Choking under pressure and working memory capacity: when performance pressure reduces fluid intelligence. Psychon Bull Rev. 2006;13(6):1005–1010.

18. Ye Q, Wang D, Guo W. Inclusive leadership and team innovation: the role of team voice and performance pressure. Eur Manage J. 2019;37(4):468–480.

19. Antwi CO, Fan C, Aboagye MO, et al. Job demand stressors and employees’ creativity: a within-person approach to dealing with hindrance and challenge stressors at the airport environment. Service Industries J. 2019;39(3–4):250–278.

20. Razinskas S, Weiss M, Hoegl M, et al. Illuminating opposing performance effects of stressors in innovation teams. J Product Innovation Manage. 2022;39(3):351–370.

21. Boulamatsi A, Liu S, Lambert LS, et al. How and when are learning adaptable newcomers innovative? Examining mechanisms and constraints. Pers Psychol. 2021;74(4):751–772.

22. Schein EH. Organizational socialization and the profession of management. Org Influence Processes. 2003;36(3):283–294.

23. Cooper D, Rockmann KW, Moteabbed S, et al. Integrator or gremlin? Identity partnerships and team newcomer socialization. Acad Management Rev. 2021;46(1):128–146.

24. Gardner HK. Performance pressure as a double-edged sword: enhancing team motivation but undermining the use of team knowledge. Adm Sci Q. 2012;57(1):1–46.

25. Liu XH, Yu HX. On the impact of university young teachers’ academic pressure on research performance: based on cognitive evaluation theory. Soc Sci Beijing. 2018;1(10):76–88.

26. Mitchell MS, Greenbaum RL, Vogel RM, et al. Can you handle the pressure? The effect of performance pressure on stress appraisals, self-regulation, and behavior. Acad Management Jo. 2019;62(2):531–552.

27. Zhao H, Liu W, Li J, et al. Leader–member exchange, organizational identification, and knowledge hiding: t he moderating role of relative leader–member exchange. J Organ Behav. 2019;40(7):834–848.

28. Hung LM, Lee YS, Lee DC. The moderating effects of salary satisfaction and working pressure on the organizational climate, organizational commitment to turnover intention. Int J Business Soc. 2018;19(1):103–116.

29. Ampofo JA, Nassè TB, Akouwerabou L. The effects of stress on performance of workers in Ghana health service in Wa municipal. Int J Manage Entrepreneurship Res. 2020;2(4):212–230.

30. Luthans F, Norman SM, Avolio BJ, et al. The mediating role of psychological capital in the supportive organizational climate: employee performance relationship. J Organ Behav. 2008;29(2):219–238.

31. Chiaburu DS, Chakrabarty S, Wang J, et al. Organizational support and citizenship behaviors: a comparative cross-cultural meta-analysis. Manage International Rev. 2015;55(5):707–736.

32. Le PB, Lei H. Determinants of innovation capability: the roles of transformational leadership, knowledge sharing and perceived organizational support. J Knowledge Manage. 2019;23(3):527–547.

33. Mwesigwa R, Tusiime I, Ssekiziyivu B. Leadership styles, job satisfaction and organizational commitment among academic staff in public universities. J Manage Dev. 2020;39(2):253–268.

34. Al-Kurdi OF, El-Haddadeh R, Eldabi T. The role of organisational climate in managing knowledge sharing among academics in higher education. Int J Inf Manage. 2020;50:217–227.

35. Wang D, Liu H. Effects of job autonomy on workplace loneliness among knowledge workers. Chine Manage Studies. 2020;15(1):182–195.

36. Park R. Autonomy and citizenship behavior: a moderated mediation model. J Managerial Psychol. 2016;30(1):280–295.

37. Noefer K, Stegmaier R, Molter B, et al. A great many things to do and not a minute to spare: can feedback from supervisors moderate the relationship between skill variety, time pressure, and employees’ innovative behavior? Creat Res J. 2009;21(4):384–393.

38. Sappleton N, Lourenço F. Work satisfaction of the self-employed: the roles of work autonomy, working hours, gender and sector of self-employment. Int J Entrepreneurship Innovation. 2016;17(2):89–99.

39. Becker WJ, Belkin LY, Tuskey SE, et al. Surviving remotely: how job control and loneliness during a forced shift to remote work impacted employee work behaviors and well‐being. Hum Resour Manage. 2022;61(4):449–464.

40. Stamper CL, Johlke MC. The impact of perceived organizational support on the relationship between boundary spanner role stress and work outcomes. J Manage. 2003;29(4):569–588.

41. Rubin RS, Dierdorff EC, Bachrach DG. Boundaries of citizenship behavior: curvilinearity and context in the citizenship and task performance relationship. Pers Psychol. 2013;66(2):377–406.

42. Connelly CE, Černe M, Dysvik A, et al. Understanding knowledge hiding in organizations. J Organ Behav. 2019;40(7):779–782.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.