Back to Journals » Patient Related Outcome Measures » Volume 10

Effects of Parkinson’s on employment, cost of care, and quality of life of people with condition and family caregivers in the UK: a systematic literature review

Authors Gumber A , Ramaswamy B, Thongchundee O

Received 26 December 2017

Accepted for publication 31 May 2019

Published 21 October 2019 Volume 2019:10 Pages 321—333

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PROM.S160843

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Robert Howland

Anil Gumber, Bhanu Ramaswamy, Oranuch Thongchundee

Faculty of Health and Wellbeing, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield S10 2BP, UK

Correspondence: Anil Gumber

Faculty of Health and Wellbeing, Sheffield Hallam University, Collegiate Hall, Sheffield S10 2BP, UK

Email [email protected]

Background: Parkinson’s is an incurable, neuro-degenerative condition with multiple symptoms substantially impacting on living conditions and quality of life (QoL) for people with Parkinson’s (PwP), most whom are older adults, and their families. The study aimed to undertake a literature review of studies conducted in the UK that quantify the direct or indirect impact of Parkinson’s on people with the condition, their families, and society in terms of out-of-pocket payments and financial consequences.

Methods: Literature was searched for Parkinson’s-related terms plus condition impact (eg, financial, employment, pension, housing, health care costs, and QoL) in the UK setting. The strategy probed several electronic databases with all retrieved papers screened for relevancy. The instruments used to measure patient-related outcomes were then examined for their relevancy in justifying the results.

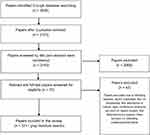

Results: The initial search retrieved 2,143 papers of which 79 were shortlisted through title and abstract screening. A full-text reading indicated 38 papers met the inclusion and quality criteria. Summary data extracted from the articles on focus, design, sample size, and questionnaires/instruments used were presented in four themes: (a) QoL and wellbeing of PwP, (b) QoL and wellbeing of caregivers and family members, (c) employment and living conditions, and (d) direct and indirect health care and societal cost.

Conclusion: UK results substantiated global evidence regarding the deterioration of QoL of PwP as the condition progressed, utilizing numerous measures to demonstrate change. Many spouses and family accept care responsibilities, affecting their QoL and finances too. The review highlighted increased health care and privately borne costs with condition progression, although UK evidence was limited on societal costs of Parkinson’s in terms of loss of employment, reduced work hours, premature retirement of PwP and caregivers that directly affected their household budget.

Keywords: Parkinson’s, HRQoL, wellbeing, employment loss, health care cost, societal cost

Introduction

Parkinson’s, a long-term condition with more than four-fifths of those affected over 60 years of age, is diagnosed through clinical investigations of movement quality (from the reduced manufacture of the neurotransmitter dopamine), causing classic motor (movement) symptoms of slowness (bradykinesia), stiffness (rigidity), and tremor.1,2 People with Parkinson’s (PwP) also experience non-motor symptoms such as depression, fatigue, and pain that manifest before many of the motor features.3 There is no cure for the condition, but early diagnosis can help in enabling the person to manage their varied symptoms through support from health professionals, voluntary services, carers, and family.4

|

Figure 1 The PRISMA flowchart of literature review selection process.Note: Adapted from Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting Items for systematic review and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6): e1000097.65 |

Of the estimated 137,000 PwP1 in 2015 in the United Kingdom (UK), prevalence rates are higher in males, with an exponential increase in both men and women beyond 60 years of age,5,6 but not varying significantly by level of deprivation and geography in the UK.5,7 The expected rise of PwP to 169,000 by 20251 in the UK means health and social care provision to address management and care will be challenging, especially in the face of an aging population. The likely impact is an enormous cost to individuals, Government, and society.

Both motor- and non-motor symptoms develop during different times over the course of the progressive condition, require diverse strategies and resource inputs. With the estimated increased cost of management is likely to impose substantial detrimental effects on quality of life (QoL). As most Parkinson’s care is informal, this impact will extend further than the PwP, encompassing carers, family, friends, and relatives.8 It is essential to understand the current cost of care, management, and effective treatments for those affected by Parkinson’s and to UK society.

To this effect, the systematic literature review gathered evidence on the impact of Parkinson’s on the socio-economic life of PwP, their families, and society based on prior UK-based research. The study sought to improve our understanding of the key components of direct and indirect health care costs associated with Parkinson’s management and care.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

Peer reviewed papers, published in the English language, reporting qualitative or quantitative UK data or gray literature which underpinned and quantified the direct and indirect impact of Parkinson’s on PwP, their families, and society were considered.

Search strategy

The research team established a literature search strategy comprising component terms for: (1) Parkinson’s, (2) condition cost-associated descriptions, eg, financial, employment, pension, housing, health care costs, and QoL, and (3) UK-based studies. All terms were searched for in the title and abstract fields, with controlled vocabulary usage as appropriate and available. Boolean operators AND and OR were used, alongside truncation, phrase searching and proximity operators. Papers were exported from ASSIA (ProQuest), CINAHL (EBSCO), Cochrane Library (Wiley), EMBASE (via National Health Service Healthcare databases), MEDLINE (EBSCO), and Web of Science (Thomson Reuters) into RefWorks (a bibliographic management tool).

Quality appraisal and study selection

Following removal of duplicates using RefWorks, 2,143 papers were obtained, and their titles and abstracts were screened for relevancy. The 79 shortlisted papers were subjected to a full-text scrutiny by two members of the research team, with a final selection of 37 papers. The included full-text papers were subjected to a quality checklist to maintain validity, quality, and to limit the probability of any bias. Whilst most of these studies were non-randomized clinical trials, we followed a simplified appraisal tool9 to assess their quality on the basis of study aims, methods, sampling, data analysis rigor, ethics and bias, findings, and their generalisability. The 42 articles excluded at this stage were rejected on the basis that seven were duplicates, four were prevalence studies of Parkinson’s and Parkinsonism, five were descriptive, eight were conference abstracts, ten were non-UK based, five were letter/advocacy papers, and three focused on validating scales/questionnaires. The search and screening process adapted from The PRISMA Group is summarized in Figure 1.

Data extraction and synthesis

Papers were read and data reviewed using a standardized extraction form encompassing: author/date, the focus of the study, research design, sample size, and questionnaires/instruments employed. The information was categorized into four themes: (a) QoL and wellbeing of PwP, (b) QoL and wellbeing of caregivers and family members, (c) employment and living conditions, and (d) direct and indirect health care and societal cost. For each category, the measures that demonstrated change were then considered in terms of how they added to this review’s aims.

Studies included for review

A majority of the articles included in the literature review investigated the impact on the QoL of PwP (16 papers), and/or QoL and wellbeing of the caregivers and family (nine papers), most of who were spouses. Ten papers estimated direct or indirect health care costs related to Parkinson’s, and just four studies focused on the impact on their employment and living conditions. Individual study topics, type, sample size, and questionnaires/instruments used in the studies are summarized in Tables 1–4.

|

Table 1 UK Studies on Parkinson’s effects on quality of life of PwP |

|

Table 2 UK studies on Parkinson’s effects on quality of life of caregivers and family members |

|

Table 3 UK Studies on changes in employment and living conditions due to Parkinson’s |

|

Table 4 UK Studies on health care and societal cost related to Parkinson’s |

Gray literature search

This was undertaken through a National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Evidence Search and on Google. Gray literature inclusion is aligned with the comprehensive review methodology previously outlined, plus helps to minimize the risk of publication bias. The search used an abridged set of terms (restricted by the resources character limits), with salient literature yielded scanned, much of which was duplicated in the electronic database search. One study was found to be relevant for inclusion in the review.

Main findings from UK studies

QoL and wellbeing of PwP

The impact on QoL and wellbeing of PwP as the condition progressed was noted from changes to both motor and non-motor symptoms in 16 studies (Table 1). These were separated into two groups based firstly on the severity and diversity of symptoms, and secondly on self-help group and social support and their interface with their health and wellbeing.

To investigate the wide-ranging symptoms, the means of obtaining results from the individual papers came from a varied selection of methods such as thematic analysis from interview methods, and measurement instruments such as self-filled and researcher administered questionnaires, asking about general health state, or specific aspects such as sleep quality, mood, disability, and adjustment. Some were condition specific and some generic, plus there were validated questionnaires or researcher-developed tools specific to their study requirements (Table 1).

Differential effects of symptoms with stages of Parkinson’s

The type of symptoms and their severity varied over the disease progression; however, started worsening in those diagnosed over 6 years.10 QoL deteriorated regardless of whether the experience was motor or non-motor, with anxiety-related reasons associated with anticipated deterioration, a large factor affecting QoL. Ten of the 16 papers used a version of the Parkinson’s Disease QoL Questionnaire (PDQ-39) covering 8 Parkinson’s-related domains (mobility, activities of daily living (ADLs), emotional wellbeing, stigma, social support, cognition, communication, and bodily discomfort)11 to measure health-related QoL (HRQoL) in PwP.

Mobility difficulties affecting walking and turning, with consequences of falling, influenced costs related to injury and increased time in the hospital, and impeded involvement in social activities. Motor symptoms significantly influenced QoL scores with lower HRQoL reported in PwP.12 A study in Scotland found the QoL of PwP who attended a movement disorders clinic as compared to a general medical clinic to be significantly higher and better.13

Non-motor symptoms are problematic in that they are experienced as distinct symptoms ranging from pain, mood, cognition, sensory, and autonomic disturbances, worsening with advancing age and Parkinson’s severity. The impact on HRQoL of PwP spans early to advanced stages of the condition, with depression, anxiety, impaired concentration, memory retrieval, sleep disturbance, and autonomic disturbance, all negatively impacting on QoL.10,12,14–17 Depression was found in at least 50% of PwP, worsening with condition progression yet despite the presence of this non-motor symptom, it was largely under-recognized and was ineffectively managed.10 A consequence of depression (measured through a HRQoL tool, the EQ-5D18), was seen as reduced health-state value at a very early stage of the condition, whilst motor impairment, insomnia, and pain affected the health-state value of PwP at a later stage of the condition.19

Unlike depression, pain was ranked highly by PwP in a survey of the three most troublesome symptoms they experienced, even at an early stage following the diagnosis, and consequently negatively affecting their QoL and contributing in raising both direct medical and other health care cost.10

Self-help groups and social support in PwP

To participate in life includes engagement in the wider sense of managing self-care as well as productive (economic) and leisure occupations, something PwP have difficulties with.20 From a semi-structured interview with PwP, it was learned that they perceived and managed the experience of living with Parkinson’s as “change”, “addressing changes”, and “reflections on living with Parkinson’s”.20 “Change” described the expected motor and non-motor symptoms experienced, but also a loss of employment, and gains in new skills due to being diagnosed with Parkinson’s. By “addressing changes”, participants included their management of medications and involvement of others in their lives as Parkinson’s progressed, what they did to stay well and how they found different ways to do things. In terms of “reflections on living with Parkinson’s”, people explored encounters with others and their own acceptance of the condition, stressing the importance of attitude (positive) and maintaining “life as usual”. Belonging to self-help groups (although there was room for them to be more supportive), and having strong social support (including close relationships), helped PwP accept the condition and adapt their lifestyle.21,22 Whilst all PwP described the loss in terms of physical and mental functioning and independence, self-identity, and the fear of future losses with the progression of the condition,22 those with having wide support reported relatively better psychological outcomes than PwP socially unsupported, who recorded higher levels of distress, anxiety and stress, and lower life satisfaction.21

For research purposes, Parkinson’s is rated according to the 5-stage disease rating scale,23 where Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) stage 3–5 relate to the later stages of Parkinson’s. As QoL deteriorates in these later stages of Parkinson’s, end of life support needs arise, especially if the person lives alone, or for a large number of people who become less physically mobile. Over two-thirds of PwP are considered to have a severe disability, with more than one-third becoming wheelchair or bed-bound,24 with the reduction in QoL noted in these patients (using the EuroQol-5D [EQ-5D]18 and PDQ-825 questionnaires) from the severity and complexity of their experienced, and untreatable non-motor and motor symptoms.

Strong social networks and close relationships become important for younger PwP, whose responses recorded lower QoL and emotional wellbeing than the older PwP, possibly due to their perception of stigma and psychosocial consequences including lower mood.26,27 Support received has to be perceived as desirable, and where the condition forces people into unwelcome choices, the QoL is negatively affected. This was clearly demonstrated by a study of the subjective wellbeing of PwP living in a care home, which was lower than in people living alone in their own home.28 Further, PwP living at home with a reduced ability to perform a chosen occupation of daily living reported poorer physical, psychological, social, and spiritual wellbeing; some of them affecting their employment and experienced distress and disappointment and thus reported deterioration in their QoL and wellbeing.29

QoL and wellbeing of caregivers and family members

Parkinson’s also affects the QoL of caregivers, which often was assessed using the condition-specific PDQ-carer questionnaire.30 Some studies used more generic questionnaires for measuring QoL of caregivers, eg, Short form (SF)-12 questionnaire to measure physical and mental health31 or self-reported wellbeing questions (Table 2). Several factors influence carer’s QoL including age (mean age ranging 68–72 years), gender (most being female spouses), health status, duration of caregiving role, the level of mobility, and cognitive function in PwP. Caregivers had a co-morbidity rate nearly five times greater when compared to the age-matched population, particularly where the PwP they lived with had psychiatric symptoms, with a comparable reduction in QoL over time in social, anxiety and depression, stress, and self-care measures affecting the social, psychological, and physical wellbeing of carers.32–37 Once falling occurred in PwP, it had a significant impact on carer’s QoL by increasing anxiety, worry, fear, anger, frustration, and shock, restricting their normal activities (indoors and outdoors), and their contact with friends and neighbours.32,38 There was too a financial impact of increasing health care costs for PwP and caregivers as falls occurred.32

Where the impact of Parkinson’s on other family members, including offspring was studied, assisting in ADL, plus a reduction in social life were the main complaints of adolescent children of PwP.40 For adult children, there was the additional stress of caring for their own family affecting QoL and wellbeing, with similarities noted in children of all aged of parents with either Parkinson’s or Multiple Sclerosis.41 The NICE guidelines for Parkinson’s disease published in 2006 and updated in 201742,43 makes no overt reference to the children of PwP although many children providing informal care to PwP expressed an issue with the lack of information about their parents’ condition.40,41

Employment and living conditions

The four studies on the financial implications of Parkinson’s examined results from previously conducted surveys, the use of researcher-decided questions, and a semi-structured interview (Table 3).

Full-time or part-time working was affected for PwP, with a reduction in employment for those in the later stages of the condition. From a review of patient surveys of PwP diagnosed more than 5 years, 6–10% were working full time, 7% part-time, and 46% were unable to work, with this percentage increasing to 82% after more than 10 years post-diagnosis.44 The same survey identified the average time lost from employment due to Parkinson’s symptoms to be 4.9 years, with gender, type of work, and living circumstances exerting a minimal influence on this figure.44

An assessment of the QoL and care of PwP attending movement disorders clinic in England, found the main problems with care related to accommodation, travel, holidays, and hobbies, with forced early retirement and waiting for welfare benefits worsened financial difficulties in PwP.45

Employment conditions altered for carers too, adding to their stress.37 One-fourth of carers had to reduce their working hours to care for someone with Parkinson’s and 30% endured a reduction in financial status,37,46 also resulting in problems accessing state welfare benefits.46

Direct and indirect health care and societal cost

The overall household economic burden of Parkinson’s was assessed through measurement of direct medical, non-medical costs, and indirect costs utilizing varied questionnaires on resource use (household and health), linking them to measures of QoL, Parkinson’s staging, health, cognitive and disability states (Table 4).

Resource use data recorded the range of annual costs of the condition from £13,80047 to £29,000,48 with direct medical costs of £1,881 per patient per annum for hospitalization, clinic appointments, and investigations. Indirect costs from informal care by family members, lost productivity and sickness ranged between £11,000 and £12,500 per person per annum.47,48 Of total care costs, 80.3% was “spent” as total informal care costs, whilst direct social cost was just 5%.47

The economic and financial strain impacted on QoL of both PwPs and carers, with most of the latter being retired and are female spouses of more male population with Parkinson’s, with underestimated costs (time and effort) underwritten by carers.47 For PwP, QoL was affected by their response to medication cycles and hence to symptom severity (worse in those with higher H&Y scores), with degraded symptoms, particularly to movement experienced in the “off” state (when medication to improve movement was not optimal), which resulted in rising costs with the longer duration since Parkinson’s diagnosis, incidence of depression, gait disturbance, and privately borne community-related costs.48 The projected total cost of Parkinson’s per year was put between £450 million to over £3 billion, with the difference accounted for by privately funded indirect costs, and prevalence rates for Parkinson’s according to the economic modeling used.49

Hospital admissions data placed elective admission for PwP at 28% of the health costs and 72% non-elective admission when compared to age and sex-matched population utilizing 60% and 40% of the total hospital costs.50 Excess bed days utilized 12% of the total costs50 from admissions related to infection, Parkinson’s or cardiac-related symptoms, with falls and hip fractures resulting in higher admission rates and costs.50 In addition to falls being a significant factor affecting QoL, co-morbidity in PwP resulted in more frequent emergency admissions and longer hospital stays, and for those over 85 years, in increased mortality than in younger PwP.50,51

Non-medical services in the community and hospital appointments, such as that provided by the Parkinson’s Disease Nurse Specialist (PNS) saved expenditure on Parkinson’s care, with an estimated annual cost savings of nearly £55,000.52 Whilst PNS intervention was not found to impact on the clinical condition of PwP, individuals reported an improvement in their wellbeing from the support.53,54

PwP accessed health and social care provision, whether living in institutional care or in their own home. The latter utilized domestic home care or personal (family provided) services, as well as community health service provision from professionals or attendance to a local day care center.55 Progression of the condition measured by H&Y score had a direct impact on health and social care costs, with the lowest costs at diagnosis (£2,971 per person) compared to at H&Y stage 5 (£18,358).56 Accommodation type affected costs, with people living in their own home utilizing services at a cost of £4,189 compared to individuals in an institutional setting who utilize services at an almost fivefold higher cost.56

Discussion

Investigating health and the consequences of ill health is complex and so is about the impact on the QoL and wellness. Measurement of health and wellness has to take into account individual perceptions, each of which will differ according to cultural understanding and societal contexts, including personal expectations of subjective wellbeing eg, happiness, plus financial, and environmental stability.57 From the health perspective, research is designed to influence the population as a collective, as in the Public Health environment, yet then rationalized to individual management by the clinician.

For a condition such as Parkinson’s, the complexity crosses a wide range of issues, ever-changing as the condition progresses.10,17,19 The motor symptoms, affecting movement, and non-motor symptoms, affecting mood, sleep, cognition, and bodily function can be measured to quantify their presence, and linked to aspects of the stage a person is at,10,11,15,16,18,23 but also to the impact of those providing support.33–41

Evidence from the articles in this review was interpreted from multiple methods of information and data gathering (see “Instruments” column in Tables 1–4), with the different measures capturing the diverse aspects of this condition.12,58 The resultant comparisons acknowledged the broad impact on the PwP and their support network, of immediate family and carers, identified in the four themes providing an understanding of how Parkinson’s affects the economic, social, financial, health, and living conditions.

A measuring tool should be chosen on the basis it could encapsulate the researcher’s expectation of change from intervention or description of a situation.58 It is now standard practice to reflect patients’ views of their position with a medical condition when designing and validating a measurement tool.59

The papers in this review gathered information through qualitative means (mainly from interview methods); self-filled questionnaires, whether condition specific eg PDQ-39 or generic eg, EQ-5D, depression or stress scales; professionally filled condition-specific and generic questionnaires, again many around cognition and mood; professionally filled subjective scales to place the person along the course of the condition eg H&Y Stage scale; and researcher-developed tools specific to a study.

Many of the instruments were canvassed to small numbers of participants and reviewed broad aspects of their Parkinson’s impact, or use standardized questions providing only a glimpse into the life for people at a particular stage of this progressive and variable condition.60 Yet the validity of some papers cannot be discounted on this basis, as they measure what the papers’ aims state they wish to quantify.58

For example, from Table 1 alone, several papers utilize the condition-specific PDQ-39 or PDQ-8 questionnaires to record the HRQoL in PwP.12–15,17,21,24,26,27 The PDQ-39,11 and shorter version PDQ-825 are categorized according to eight domains identified from a survey with PwP about issues affecting their QoL. These measures provide a snapshot into the lives of people by rating the person according to medically defined Parkinson’s-specific scales through the use of the H&Y disease stage scale23 or the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale,61 a scale of subjectively recognized and medically assessed symptoms. Although this version of the scale has been updated to a more patient-involved tool, the new version is not widely used yet.

Opinions of PwP have been sought in varied ways from the request to complete a booklet with several different questionnaires listing aspects from mobility to depression and anxiety for the PwP to rate;12 a survey of freely chosen and ranked three most troublesome symptoms affecting the QoL of the people who attended clinics,10 to the researchers quantifying symptoms such as reported ADL or evaluation of disability.14 The majority of the tools, however, are still presented as numerical scales, or based on subjective decisions of the medical professional or researchers. Categorizing information on behalf of PwP is questionable in terms of the meaningfulness of the responses.62

The qualitative paper authors strove for a process and outcomes of relevance to the specific people participating in the research. For example, in Benharoch and Wiseman’s phenomenological approach,20 the semi-structured interviews of PwP are used as a basis from which to guide the interview, thus following issues the participants raised as important to them. Where semi-structured interviews were undertaken by Barrow and Charlton,22 the chosen questions were initially developed through pilot discussions from people in the types of groups they would then go on to interview.

The tools and methods of gathering information in the review articles neither permit clear relational interpretation nor differentiate person-specific issues eg, problems in coping with treatment or self-management. The wide-ranging approaches do not identify the construction of categories that influence the QoL of PwP, factors such as employment, or the costs of the condition to themselves and across society. There was also lack of reporting of incidence and prevalence of Parkinson’s by the individual UK home countries especially Northern Ireland.

Yet what is seen are patterns from the UK evidence suggesting that Parkinson’s management and care responsibility has fallen on spouses and extended family members of PwP directly affecting QoL, wellbeing, and financial status. Where QoL in PwP deteriorated as the condition progressed (particularly as non-motors symptoms including sleep disorders and depression increased over time), the impact was experienced in rising stress and fatigue level among carers with incidences such as falls in PwP identified as the most significant factor impacting on both caregiver’s and PwP social life and wellbeing. The frequent occurrence of falling lessened the chances for caregivers to go out for their normal activities and consequently decreased their contact with friends and neighbours.

The challenging role of caregivers often goes unrecognized. Spouses acting as informal carers are also aging with their own health problems, whilst adapting to reduced independence, increased social isolation, physical exhaustion, and psychological stress. That carers’ burden, which is a major source for economic and financial cost, has not been factored into cost-effectiveness analyses.63 Recognition of this would ensure better assessment of carers’ needs and respite provision to help in sustaining their efforts and energy for continued care to PwP, thus improving HRQoL of carers.63

Although not reviewed across the course of Parkinson’s, the UK-based evidence suggests a more than double increase in total annual costs of Parkinson’s per case, from 2006 (£13,800) to 2011 (£29,000). Non-medical costs, including informal care accounted for the majority of the expenses, whilst health care cost was the greatest due to unplanned hospital admissions for PwP and their extending length of hospital stay compared to the general population.

There was evidence of loss of employment, reduced work hours, premature retirement of both PwP and caregivers, worsening according to condition progression after 5 years post-diagnosis, with time off work also noted after this timeframe. Parkinson’s created financial difficulties from forced retirement and delays in receiving welfare benefits. No UK-based study looked comprehensively at how Parkinson’s affected employment or working conditions of carers, including private expenditure to maintain household living standards.

Conclusion

Deterioration of QoL of both the PwP and caregivers as the condition progresses puts a tremendous economic and financial burden on the household of the PwP and society in terms of social care and health care delivery costs.

The incurable and long-term nature of this neuro-degenerative condition creates multi-factorial and complex symptoms which have a substantial impact on QoL, more so as the condition progresses, and particularly as an individual becomes less able to look after him or herself. Parkinson’s care tends to be provided informally, as family members and friends take on a carer role to assist the PwP, with more cost of managing Parkinson’s attributed to informal and social care, rather than direct medical costs. The literature highlights deterioration in QoL of PwP plus their carers and family members over time, both in economic and social terms. Whilst evidence is limited in assessing income loss from changes in employment to the households of PwP, as well as out-of-pocket expenditure incurred in accessing both health and social care services, it is shown that family members volunteer time, alter employment status and utilize their own resources, developing stress and health problems alongside the deterioration of the person they care for, thus accentuating the total societal costs.

The literature highlights the critical role of the support services (especially the PNS) in the management and care of the condition, reiterating a need for provision that strengthens and extends services to PwP and their families. Crucial gaps were identified in the existing evidence by various stakeholders for addressing everyday practicalities in the management of the complexities of Parkinson’s; a priority for Parkinson’s research agenda.64

Acknowledgments

This paper draws from a larger study funded by Parkinson’s UK on the Cost of Parkinson’s. The detailed research report entitled ‘Economic, Social and Financial Cost of Parkinson’s on Individuals, Carers and their Families in the UK’ by Gumber et al. 2017, is available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/15930/.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Parkinson’s UK. The incidence and prevalence of Parkinson’s in the UK: results from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink-Reference Report; 2017. Available from: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-01/Prevalence%20%20Incidence%20Report%20Latest_Public_2.pdf.

2. Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30(12):1591–1601. doi:10.1002/mds.26424

3. Schrag A, Horsfall L, Walters K, Noyce A, Petersen I. Prediagnostic presentations of Parkinson’s disease in primary care: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;14(1):57–64. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70287-X

4. Baker MG, Graham L. The journey: Parkinson’s disease. Bmj. 2004;329:611–614. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7466.611

5. Caslake R, Taylor K, Scott N, et al. Age-, gender-, and socioeconomic status-specific incidence of Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism in North East Scotland: the PINE study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19(5):515–521. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.01.014

6. Wickremaratchi MM, Perera D, O’Loghlen C, et al. Prevalence and age of onset of Parkinson’s disease in Cardiff: a community based cross sectional study and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(7):805–807. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2008.162222

7. Horsfall L, Petersen I, Walters K, Schrag A. Time trends in incidence of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis in UK primary care. J Neurol. 2013;260(5):1351–1357. doi:10.1007/s00415-012-6804-z

8. Williamson C, Simpson J, Murray C. Caregivers’ experiences of caring for a husband with Parkinson’s disease and psychotic symptoms. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:583–589. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.04.014

9. Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(9):1284–1299. doi:10.1177/1049732302238251

10. Politis M, Wu K, Molloy S, Bain PG, Chaudhuri KR, Piccini P. Parkinson’s disease symptoms: the patient’s perspective. Mov Disord. 2010;25(11):1646–1651. doi:10.1002/mds.23135

11. Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Peto V, Greenhall R, Hyman N. The Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39): development and validation of a Parkinson’s disease summary index score. Age Ageing. 1997;26(5):353–357. doi:10.1093/ageing/26.5.353

12. Rahman S, Griffin HJ, Quinn NP, Jahanshahi M. Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: the relative importance of the symptoms. Mov Disord. 2008;23(10):1428–1434. doi:10.1002/mds.21667

13. Blackwell AD, Brown VJ, Rochow SB. Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: movement disorders clinic vs general medical clinic – a comparative study. Scott Med J. 2005;50(1):18–20. doi:10.1177/003693300505000107

14. Leroi I, Ahearn DJ, Andrews M, Mcdonald KR, Byrne EJ, Burns A. Behavioural disorders, disability and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Age Ageing. 2011;40:614–621. doi:10.1093/ageing/afr078

15. Findley L, Eichhorn T, Janca A, et al. Factors impacting on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: results from an international survey. Mov Disord. 2002;17(1):60–67. doi:10.1002/mds.10010

16. Duncan GW, Khoo TK, Yarnall AJ, et al. Health-related quality of life in early Parkinson’s disease: the impact of nonmotor symptoms. Mov Disord. 2014;29(2):195–202. doi:10.1002/mds.25664

17. Simpson J, Lekwuwa G, Crawford T. Predictors of quality of life in people with Parkinson’s disease: evidence for both domain specific and general relationships. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(23):1964–1970. doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.883442

18. Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):337–343. doi:10.3109/07853890109002087

19. Shearer J, Green C, Counsell CE, Zajicek JP. The impact of motor and non motor symptoms on health state values in newly diagnosed idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2012;259(3):462–468. doi:10.1007/s00415-011-6202-y

20. Benharoch J, Wiseman T. Participation in occupations: some experiences of people with Parkinson’s disease. Br J Occup Ther. 2004;67(9):380–387. doi:10.1177/030802260406700902

21. Simpson J, Haines K, Lekwuwa G, Wardle J, Crawford T. Social support & psychological outcome in people with Parkinson’s disease: evidence for a specific pattern of associations. Br J Clin Psychol. 2006;45(4):585–590. doi:10.1348/014466506X96490

22. Barrow CJ, Charlton GS. Coping and self-help group membership in Parkinson’s disease: an exploratory qualitative study. Health Social Care Community. 2002;10(6):472–478.

23. Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17(5):427–442. doi:10.1212/WNL.17.5.427

24. Higginson IJ, Gao W, Saleem TZ, et al. Symptoms and quality of life in late stage Parkinson syndromes: a longitudinal community study of predictive factors. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e46327–e46327. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046327

25. Jenkinson C, Fitzptrick R, Peto V, Greenhall R, Hyman N. The PDQ-8: development and validation of a short-form parkinson’s disease questionnaire. Psychol Health. 1997;12(6):805–814. doi:10.1080/08870449708406741

26. Knipe MD, Wickremaratchi MM, Wyatt-Haines E, Morris HR, Ben-Shlomo Y. Quality of life in young-compared with late-onset Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26(11):2011–2018. doi:10.1002/mds.23763

27. Lawson RA, Yarnall AJ, Duncan GW, et al. Severity of mild cognitive impairment in early Parkinson’s disease contributes to poorer quality of life. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(10):1071–1075. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.07.004

28. Cubi-Molla P, de Vires J, Devlin N. A study of the relationship between health and subjective well-being in Parkinson’s disease patients. Value Health. 2014;17(4):372–379. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2014.03.002

29. Murdock C, Cousins W, Kernohan WG. “Running water won’t freeze”: how people with advanced Parkinson’s disease experience occupation. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(5):1363–1372. doi:10.1017/S1478951514001357

30. Jenkinson C, Dummett S, Kelly L, et al. The development and validation of a quality of life measure for the carers of people with Parkinson’s disease (the PDQ-Carer). Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(5):483–487. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.01.007

31. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales.

32. Davey C, Wiles R, Ashburn A, Murphy C. Falling in Parkinson’s disease: the impact on informal caregivers. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(23):1360–1366.

33. O’Reilly F, Finnan F, Allwright S, Smith G, Benshlomo Y. The effects of caring for a spouse with Parkinson’s disease on social, psychological and physical well-being. BrJ Gen Pract. 1996;46(410):507–512.

34. Kudlicka A, Clare L, Hindle JV. Quality of life, health status and caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease: relationship to executive functioning. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(1):68–76. doi:10.1002/gps.3970

35. Peters M, Fitzpatrick R, Doll H, Playford D, Jenkinson C. Does self-reported well-being of patients with Parkinson’s disease influence caregiver strain and quality of life? Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17(5):348–352. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.02.009

36. Peters M, Jenkinson C, Doll H, Playford ED, Fitzpatrick R. Carer quality of life and experiences of health services: a cross-sectional survey across three neurological conditions. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:103. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-11-103

37. Drutyte G, Forjaz MJ, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Martinez-Martin P, Breen KC. What impacts on the stress symptoms of Parkinson’s carers? Results from the Parkinson’s UK Members’ survey. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(3):199–204. doi:10.3109/09638288.2013.782363

38. Morley D, Dummett S, Peters M, et al. Factors influencing quality of life in caregivers of people with Parkinson’s disease and implications for clinical guidelines. Parkinson’s Dis. 2012;2012:190901.

39. Schrag A, Hovris A, Morley D, Quinn N, Jahanshahi M. Caregiver-burden in Parkinson’s disease is closely associated with psychiatric symptoms, falls, and disability. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2006;12(1):35–41. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2005.06.011

40. Schrag A, Morley D, Quinn N, Jahanshahi M. Impact of Parkinson’s disease on patients’ adolescent and adult children. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2004;10(7):391–397. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.03.011

41. Morley D, Selai C, Schrag A, Jahanshahi M, Thompson A. Adolescent and adult children of parents with Parkinson’s disease: incorporating their needs in clinical guidelines. Parkinson’s Dis. 2011;2011:951874. doi:10.4061/2011/153979

42. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Parkinson’s Disease: National Clinical Guideline for Diagnosis and Management in Primary and Secondary Care CG35. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2006.

43. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Parkinson’s Disease in Adults. NG71. London: NICE; 2017.

44. Schrag A, Banks P. Time of loss of employment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21(11):1839–1843. doi:10.1002/mds.21030

45. Clarke C, Zobkiw R, Gullaksen E. Quality of life and care in Parkinson’s disease. Br J Clin Pract. 1995;49(6):288–293.

46. Mclaughlin D, Hasson F, Kernohan WG, et al. Living and coping with Parkinson’s disease: perceptions of informal carers. Palliat Med. 2011;25(2):177–182. doi:10.1177/0269216310385604

47. McCrone P, Allcock LM, Burn DJ. Predicting the cost of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22(6):804–812. doi:10.1002/mds.21360

48. Findley LJ, Wood E, Lowin J, Roeder C, Bergman A, Schifflers M. The economic burden of advanced Parkinson’s disease: an analysis of a UK patient dataset. J Med Econ. 2011;14(1):130–139. doi:10.3111/13696998.2010.551164

49. Findley LJ. The economic impact of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13:S8–S12. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.06.003

50. Low V, Ben-Shlomo Y, Coward E, Fletcher S, Walker R, Clarke CE. Measuring the burden and mortality of hospitalisation in Parkinson’s disease: a cross-sectional analysis of the English hospital episodes statistics database 2009–2013. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21(5):449–454. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.01.017

51. Xin Y, Clarke CE, Muzerengi S, et al. Treatment reasons, resource use and costs of hospitalizations in people with Parkinson’s: results from a large RCT. Value Health. 2014;17(7):A809. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2014.08.541

52. Hobson P, Roberts S, Meara J. What is the economic utility of introducing a Parkinson’s disease nurse specialist service? Clinician (Goa). 2003;3:1–3.

53. Jarman B, Hurwitz B, Cook A, Bajekal M, Lee A. Effects of community based nurses specialising in Parkinson’s disease on health outcome and costs: randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2002;324(7345):1072–1075. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7345.1072

54. Hurwitz B, Jarman B, Cook A, Bajekal M. Scientific evaluation of community-based Parkinson’s disease nurse specialists on patient outcomes and health care costs. J Eval Clin Pract. 2005;11(2):97–110. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2005.00495.x

55. Walker R, Sweeney W, Gray W. Access to care services for rural dwellers with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Br J Neurosci Nurs. 2011;7(2):494–496. doi:10.12968/bjnn.2011.7.2.494

56. Findley L, Aujla M, Bain PG, et al. Direct economic impact of Parkinson’s disease: a research survey in the United Kingdom. Mov Disord. 2003;18(10):1139–1145. doi:10.1002/mds.10507

57. Corbin CB, Pangrazi RP. Toward a Uniform definition of wellness: a commentary. President’s Counc Phys Fitness Sports. 2001;3(15):1–8.

58. Coster W. Making the best match: selecting outcome measures for clinical trials and outcome studies. Am J Occup Ther. 2013;67(2):162–170. doi:10.5014/ajot.2013.006015

59. Eton DT, Elraiyah TA, Yost KJ, et al. A systematic review of patient-reported measures of burden of treatment in three chronic diseases. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2013;4:7–20. doi:10.2147/PROM

60. Kelley K, Clarke B, Brown V, Sitzia J. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(3):261–266. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzg031

61. Fahn S, Elton RL; UPDRS Program Members. Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. In: Fahn S, Marsden CD, Goldstein M, Calne DB, editors. Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease, Vol. 2. Florham Park, NJ: Macmillan Healthcare Information; 1987:

62. Allen E, Seaman C. Likert scales and data analysis. Qual Prog. 2007;40(7):64–65.

63. Dowding CH, Shenton CL, Salek SS. A review of the health-related quality of life and economic impact of Parkinson’s disease. Drugs Aging. 2006;23(9):693–721. doi:10.2165/00002512-200623090-00001

64. Deane KHO, Flaherty H, Daley DJ, et al. Priority setting partnership to identify the top 10 research priorities for the management of Parkinson’s disease. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006434. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006434

65. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J,Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting Items for systematic review and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6): e1000097.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.