Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 9

Effects of parecoxib on postoperative pain and opioid-related symptoms following gynecologic surgery

Authors Parsons B , Zhu Q, Xie L, Li C, Cheung R

Received 30 April 2016

Accepted for publication 23 June 2016

Published 25 November 2016 Volume 2016:9 Pages 1101—1107

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S111733

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Michael Schatman

Bruce Parsons,1 Qijiang Zhu,2 Li Xie,3 Chunming Li,1 Raymond Cheung1

1Pfizer Inc, New York, NY, USA; 281st Hospital of Chinese People’s Liberation Army, Nanjing, People’s Republic of China; 3Pfizer Investment Co., Ltd, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

Objective: To examine the analgesic and opioid-sparing effects of parecoxib following major gynecologic surgery.

Methods: This is a large subset analysis of patients from a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of parecoxib/valdecoxib (PAR/VAL) for postoperative pain. Pain severity, pain interference with function, opioid use, occurrence of opioid-related symptoms, and Patient/Physician Global Evaluation of Study Medication were compared between placebo and PAR/VAL treatment groups in the days following surgery.

Results: Pain scores were reduced in the PAR/VAL group (n=98), relative to placebo (n=97), on Day 2 (−21%, P<0.001) and Day 3 (−23%, P=0.004). Pain interference with function scores were also significantly lower in the PAR/VAL group, compared with placebo, on Day 2 (−29%, P<0.001) and Day 3 (−28%, P=0.013). Consumption of supplemental morphine was significantly lower in the PAR/VAL group relative to placebo at 24 hours (−37%, P=0.010) and trended lower at 48 (−28%) and 72 hours (−26%). Patients in the PAR/VAL group also had a reduced risk of experiencing specific opioid-related symptoms, including “inability to concentrate” (relative risk =0.53) and “nausea” (relative risk =0.60) on Day 2. Both Patient and Physician Global Evaluation of Study Medication scores were better in the PAR/VAL group than in the placebo group.

Conclusion: The current study adds support for the use of parecoxib in patients following major gynecologic surgery.

Keywords: parecoxib, postoperative pain, gynecologic surgery

Introduction

Management of pain following surgery remains a challenge to both patients and physicians. In a recent prospective study of 441 inpatients undergoing orthopedic, general, neurosurgical, or gynecologic surgery, over half of patients reported “moderate-to-extreme” pain at the time of discharge and 12% reported “severe-to-extreme” pain.1 Opioids have demonstrated efficacy for the management of pain following surgery and are commonly used in the postoperative setting.2 Opioids, however, are associated with a variety of dose-dependent adverse symptoms, including drowsiness, confusion, nausea, constipation, respiratory depression, and itching, among others.3,4 Current postoperative analgesia guidelines aim to reduce the amount of opioids consumed and the frequency of opioid-associated adverse events.5 A multimodal pain management approach is recommended in which, unless contraindicated, patients receive around-the-clock treatment with acetaminophen and nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or selective cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors in addition to, or instead of, opioid-based analgesia.5

Although they provide an analgesic effect, nonselective NSAIDs that inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2 can inhibit platelet aggregation and may increase the risk of bleeding during and following surgery.6,7 These effects are mainly attributed to inhibition of COX-1. COX-2-selective inhibitors, in contrast, provide analgesic benefits similar to those of nonselective NSAIDs but with less risk for bleeding.8,9 Thus, COX-2 selective inhibitors are an attractive analgesic option in the postoperative setting.

Gynecologic surgeries are among the most common types of surgeries, with hysterectomy being the second most common surgery among women in the United States at nearly 500,000 cases per year.10 Though studies have examined the use of opioids following major gynecological surgery, there are relatively few studies examining the use of NSAIDs, and even fewer examining the use of COX-2 selective inhibitors in this setting. Therefore, the current analysis examines the analgesic efficacy and potential for opioid sparing of parecoxib, an injectable COX-2 selective inhibitor, in patients following major gynecologic surgery.

Methods

Data sources

This is a large subset analysis of patients from a previous multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of parecoxib, followed by valdecoxib for the treatment of pain following a variety of noncardiac surgeries. Detailed methods and results of this trial have been published previously.11,12 The subgroup analyzed here comprised 195 patients undergoing major gynecologic surgery. As in the original trial, patients were aged 18–80 years, were expected to require in-hospital analgesic treatment for postoperative pain for at least 3 full days and analgesic treatment following discharge over a 10-day period following surgery, and were required to have an American Society of Anesthesiologists Grade I–III for preoperative health. The original clinical trial was approved by the appropriate institutional review boards, and all patients provided informed consent.

Treatment

After recovery from anesthesia, eligible patients were randomized to parecoxib/valdecoxib (PAR/VAL) or matching placebo. PAR/VAL treatment consisted of an initial 40 mg intravenous (IV) dose of PAR (on Day 1) and 20 mg IV or intramuscular (IM) doses of PAR every 12 hours thereafter (through Day 3), followed by 20 mg oral doses of VAL every 12 hours (until Day 10).

Supplemental analgesia was allowed throughout the course of the study in the form of morphine with patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) or bolus administration during the IV/IM treatment period and codeine/acetaminophen or hydrocodone/acetaminophen during the oral treatment period of this study. The PCA protocol included PCA pump on demand (no basal infusion) at 1 mg/mL administered at 1.0 mg per dose, with a block out time of 6 minutes.

Analyses

Patients rated pain intensity throughout each day on a scale, from 0= none to 3= severe. Summed pain intensity over 24 hours was calculated as previously described11 and compared between treatment groups on Days 2 and 3, using an analysis of variance model with country and treatment as factors and a last observation carried forward approach to missing data.

A composite score was derived from five items of the pain interference with function question of the modified Brief Pain Inventory – short form.13 Composite scores were presented for Days 2 and 3 and were compared between treatment groups using a general linear model with treatment and country as factors and a last observation carried forward approach to missing data.

The cumulative amount of supplemental morphine (PCA and bolus) consumed at 24, 48, and 72 hours after the initial dose of study treatment was compared between treatment groups using an analysis of variance model with treatment and country as factors.

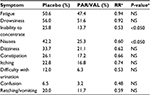

Patients used the Opioid-Related Symptom Distress Scale14 to rate their distress from common opioid-related symptoms, including fatigue, drowsiness, inability to concentrate, confusion, dizziness, constipation, itching, difficulty with urination, nausea, and retching/vomiting. The percentage of patients experiencing each opioid-related symptom was calculated for each treatment group on Day 2. A relative risk (RR; PAR/VAL versus placebo) was calculated for each symptom, and significance was assessed using a Fisher’s exact test. Additionally, the RR (PAR/VAL versus placebo) of experiencing ≥1, ≥2, and ≥3 symptoms on Day 2 was also assessed for each treatment group.

Patient and Physician Global Evaluation of Study Medication scores were assessed at the time of transition from IV/IM to oral dosing. Scores ranged from 1= poor to 4= excellent, and were compared between treatment groups using a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test controlling for country.

All analyses were performed using the modified intent-to-treat population, which consisted of all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study medication.

Results

In total, 195 patients were included in the analysis (PAR/VAL, n=98; placebo, n=97). The types of gynecological procedures included in the analysis were as follows: uterine (n=97), adnexa (n=9), other (n=21), uterine and other (n=12), adnexa and other (n=1), uterine and adnexa (n=54), uterine and adnexa and other (n=1) (Table 1). Basic patient demographics were similar between the PAR/VAL and placebo treatment groups (Table 1). Two patients (one in each treatment group) were classified as male. One patient had a diagnosis of uterine carcinoma, whereas the other had a diagnosis of uterine bleeding with multiple fibroids. It is uncertain whether this was an error (by the patient or sponsor) when reporting sex or whether these patients intentionally reported their sex as male.

| Table 1 Demographics of all randomized patients Abbreviations: PAR/VAL, parecoxib/valdecoxib; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index. |

Mean summed pain intensity over 24 hours pain scores were significantly lower among patients receiving PAR/VAL than patients receiving placebo. Pain scores were reduced by 21% (an absolute reduction of 7.2 points on a scale from 0 to 72) in the PAR/VAL group relative to placebo on Day 2 (P<0.001, Figure 1). A similar reduction (23%, an absolute reduction of 6.2 points) was evident on Day 3 (P=0.004, Figure 1). Mean composite modified Brief Pain Inventory – short form pain interference with function scores were also significantly lower in the PAR/VAL group compared with placebo. Relative to placebo, scores were reduced by 29% (an absolute reduction of 1.2 points on a scale from 0 to 10, P<0.001) on Day 2 and 28% (an absolute reduction of 0.7 points, P=0.013) on Day 3 (Figure 2).

In addition to experiencing an analgesic benefit, patients receiving PAR/VAL generally consumed less supplemental morphine following surgery than patients receiving placebo. Consumption of supplemental morphine was significantly lower at 24 hours (−37%, absolute reduction of 11.1 mg morphine equivalents, P=0.010) and trended lower at 48 (−28%, absolute reduction of 13.2 mg morphine equivalents, P=0.113) and 72 hours (−26%, absolute reduction of 14.6 mg morphine equivalents, P=0.229) (Figure 3). Notably, less morphine consumption in the PAR/VAL treatment group was accompanied by a reduced risk of experiencing specific opioid-related symptoms, including “inability to concentrate” (RR =0.53) and “nausea” (RR =0.60) on Day 2 following surgery (Table 2). The overall RR of experiencing ≥2 opioid-related symptoms on Day 2 was significantly lower with PAR/VAL compared with placebo (RR =0.80, P<0.050).

| Table 2 Frequency of opioid-related symptoms on Day 2 following surgery Note: aPAR/VAL compared with placebo. Abbreviations: NS, nonsignificant; PAR/VAL, parecoxib/valdecoxib; RR, relative risk. |

Patients and physicians rated their impression of study medication at the time of transition from IV/IM parecoxib to oral valdecoxib dosing. There was a significant difference in the distribution of Patient (P<0.001; Figure 4A) and Physician (P<0.001; Figure 4B) Global Evaluation of Study Medication scores between the PAR/VAL and placebo groups. Notably, 48% of both patients and physicians in the PAR/VAL group rated treatment as “excellent” compared with only 26% (patients) and 21% (physicians) in the placebo group. Further, considerably less patients and physicians in the PAR/VAL group rated their treatment as “poor” or “fair” compared with the placebo group.

Discussion

On Days 2 and 3 following major gynecologic surgery, patients receiving parecoxib reported significantly lower pain severity scores compared with patients receiving placebo. Additionally, patients treated with parecoxib reported significantly lower pain interference with function scores than those treated with placebo. This analgesic benefit was accompanied by an opioid-sparing effect. At 24 hours after the initial dose of study medication, patients receiving parecoxib consumed 37% less morphine than patients receiving placebo. The risk of experiencing ≥2 opioid-related symptoms was also reduced in patients treated with parecoxib compared with patients receiving placebo. The utility of parecoxib in the postoperative setting was supported by the finding that Global Evaluation of Study Medication scores were considerably better in the PAR/VAL group than in the placebo group at the time of transition from IV/IM parecoxib to oral valdecoxib. Indeed, nearly half of all patients and physicians rated parecoxib as “excellent”, whereas only 5% rated treatment as “poor”.

Although the clinical trial that our analysis was based upon was designed before enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols had been developed, the results of our analysis demonstrate that parecoxib is an excellent choice for such protocols. ERAS protocols are multimodal perioperative care approaches designed to promote early recovery after surgery.15,16 A growing body of evidence suggests that implementation of such protocols leads to improved outcomes.15,17–19 Early mobilization is a key element of ERAS protocols,15,20,21 but both pain and opioid-related symptoms hinder patient function/mobilization and have the potential to increase the length of recovery.3,4 Notably, our analysis demonstrated that patients receiving parecoxib following gynecologic surgery had significantly better pain and pain interference with function scores compared with patients receiving placebo. This was evident on both Days 2 and 3 following surgery. Some evidence suggests that opioids, while effective for pain at rest, are less effective with respect to movement-induced pain.22,23 NSAIDs, in contrast, have been shown to be effective for movement-induced pain, and previous studies have shown that parecoxib significantly reduces movement-induced pain compared with morphine.24–26 Although movement-induced pain was not directly assessed in our analysis, patient movements were not restricted. This represents a real-world setting where some patients would have had pain assessments after some unavoidable movement. Since parecoxib was shown to significantly reduce pain after an aggravating movement in two previous studies of gynecological surgery,25,26 it is reasonable to speculate that the greater pain reduction in the parecoxib plus PCA group, compared with the PCA alone group, seen in the current analysis may be due to effects of parecoxib on movement-induced pain.

As mentioned earlier, opioid-related symptoms may also hinder early mobilization and lead to increased length of recovery. The risk of nausea and vomiting is of particular concern following gynecologic surgery, and minimizing these opioid-induced events is a key goal in perioperative analgesic approaches.27 In our analysis, patients receiving parecoxib consumed 37% less morphine compared to patients receiving placebo at 24 hours after the initial dose of study medication. Notably, the risk of nausea was significantly reduced on Day 2 following surgery, and the number of patients experiencing retching or vomiting in the parecoxib group was 11.7% compared with 20.0% in the placebo group, although the risk difference between these two groups did not reach the level of statistical significance. Overall, the risk of experiencing ≥2 opioid-related symptoms was significantly reduced in patients treated with parecoxib compared with placebo, demonstrating that lower opioid consumption in this group resulted in fewer opioid-related adverse events. An additional benefit of lowering the opiate requirement is the potential for savings on overall treatment costs. For example, significant cost savings were associated with the use of parecoxib, compared with opioids alone, over a 3- to 5-day period in a randomized double-blind trial of patients following noncardiac surgery.28 These savings were attributed to a reduction in the occurrence and treatment of opioid-related adverse events.

The analgesic and opioid-sparing effects observed with parecoxib in our analysis support its use following gynecologic surgery. It should be noted, however, that our findings are limited in that they are a result of a retrospective subset analysis in which the original trial was powered to examine the safety of PAR/VAL treatment. In addition, pain assessments and measures of opioid sparing were secondary, though prespecified, end points.

Despite these limitations, several factors offer support to our findings. First, though this was a subset analysis, a total of 195 patients were analyzed and the parecoxib group (n=98) was larger than the parecoxib group(s) of many previous trials.25,26,29 Additionally, our findings compare favorably to previous studies of parecoxib following gynecologic surgery. Short-term studies have demonstrated that patients receiving parecoxib have lower pain scores and better evaluation of study medication scores over the initial 24 hours following total abdominal hysterectomy or myomectomy via laparotomy than patients receiving placebo.25,26,30 Similar results were seen in studies that extended out to 2 or 3 days.29,31 As in our study, parecoxib significantly improved pain interference with function scores compared with placebo on Days 2 and 3 in the only previous study to report on this outcome.31 Although opioid-sparing effects only reached statistical significance at 24 hours in our study, such effects have been reported at 24, 48, and 72 hours after gynecologic surgery.29,31,32 Second, the parecoxib dosing schedule in the clinical trial that our analyses were based on parallels parecoxib prescribing guidelines in many parts of the world that recommend a 20- or 40-mg IV or IM dose, followed every 6–12 hours by 20- or 40-mg doses as required, not to exceed 80 mg/d. Typical parecoxib treatment duration is 3–7 days, and those in our analysis received parecoxib at least through postoperative Day 3, whereupon they received oral valdecoxib through Day 10. Importantly, the efficacy end points were examined on Days 2 and 3 when patients received parecoxib as opposed to valdecoxib.

Conclusion

Overall, our analysis demonstrates that patients receiving parecoxib reported significantly lower pain severity scores, reported significantly lower pain interference with function scores, consumed significantly less supplemental morphine, and were at less risk for experiencing multiple opioid-related symptoms in the days immediately following gynecologic surgery than patients receiving placebo. As treatment guidelines continue to de-emphasize the use of opioids for postoperative pain, these results add further support for the use of parecoxib in this setting.

Acknowledgment

Medical writing support was provided by Matt Soulsby, PhD, CMPP, of Engage Scientific Solutions and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Disclosure

The original clinical trial and this subset analysis were sponsored by Pfizer Inc. Bruce Parsons, Li Xie, Chunming Li, and Raymond Cheung are full-time employees of Pfizer and own stock in Pfizer. The authors report no other conflicts of interests in this work.

References

Buvanendran A, Fiala J, Patel KA, Golden AD, Moric M, Kroin JS. The incidence and severity of postoperative pain following inpatient surgery. Pain Med. 2015;16(12):2277–2283. | ||

Ramsay MA. Acute postoperative pain management. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2000;13(3):244–247. | ||

Wheeler M, Oderda GM, Ashburn MA, Lipman AG. Adverse events associated with postoperative opioid analgesia: a systematic review. J Pain. 2002;3(3):159–180. | ||

Zhao SZ, Chung F, Hanna DB, Raymundo AL, Cheung RY, Chen C. Dose-response relationship between opioid use and adverse effects after ambulatory surgery. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(1):35–46. | ||

The American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(2):248–273. | ||

Schafer AI. Effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on platelet function and systemic hemostasis. J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;35(3):209–219. | ||

Maund E, McDaid C, Rice S, Wright K, Jenkins B, Woolacott N. Paracetamol and selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the reduction in morphine-related side-effects after major surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106(3):292–297. | ||

Noveck R, Laurent A, Kuss M, Talwalker S, Hubbard R. Parecoxib sodium does not impair platelet function in healthy elderly and non-elderly individuals. Clin Drug Investig. 2001;21(7):465–476. | ||

Leese PT, Hubbard RC, Karim A, Isakson PC, Yu SS, Geis GS. Effects of celecoxib, a novel cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, on platelet function in healthy adults: a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;40(2):124–132. | ||

Office on Women’s Health, US Department of Health and Human Services (online). Hysterectomy, 2014. Available from: http://www.womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/hysterectomy.html. Accesssed February 10, 2016. | ||

Nussmeier NA, Whelton AA, Brown MT, et al. Safety and efficacy of the cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib after noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(3):518–526. | ||

Langford RM, Joshi GP, Gan TJ, et al. Reduction in opioid-related adverse events and improvement in function with parecoxib followed by valdecoxib treatment after non-cardiac surgery. Clin Drug Investig. 2009;29(9):577–590. | ||

Mendoza T, Mayne T, Rublee D, Cleeland C. Reliability and validity of a modified Brief Pain Inventory short form in patients with osteoarthritis. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(4):353–361. | ||

Apfelbaum JL, Gan TJ, Zhao S, Hanna DB, Chen C. Reliability and validity of the perioperative opioid-related symptom distress scale. Anesth Analg. 2004;99(3):699–709, table of contents. | ||

Ljungqvist O. ERAS – enhanced recovery after surgery: moving evidence-based perioperative care to practice. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38(5):559–566. | ||

Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78(5):606–617. | ||

Kagedan DJ, Ahmed M, Devitt KS, Wei AC. Enhanced recovery after pancreatic surgery: a systematic review of the evidence. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17(1):11–16. | ||

Steele SR, Bleier J, Champagne B, et al. Improving outcomes and cost-effectiveness of colorectal surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(11):1944–1956. | ||

Hughes MJ, McNally S, Wigmore SJ. Enhanced recovery following liver surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16(8):699–706. | ||

Kehlet H, Dahl JB. Anaesthesia, surgery, and challenges in postoperative recovery. Lancet. 2003;362(9399):1921–1928. | ||

Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg. 2002;183(6):630–641. | ||

Kehlet H, Holte K. Effect of postoperative analgesia on surgical outcome. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87(1):62–72. | ||

McQuay H. Opioids in pain management. Lancet. 1999;353(9171):2229–2232. | ||

Pfizer. Protocol PARA-0505-080 (data on file). | ||

Barton SF, Langeland FF, Snabes MC, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravenous parecoxib sodium in relieving acute postoperative pain following gynecologic laparotomy surgery. Anesthesiology. 2002;97(2):306–314. | ||

Bikhazi GB, Snabes MC, Bajwa ZH, et al. A clinical trial demonstrates the analgesic activity of intravenous parecoxib sodium compared with ketorolac or morphine after gynecologic surgery with laparotomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(4):1183–1191. | ||

Gan TJ, Diemunsch P, Habib AS, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(1):85–113. | ||

Muszbek N, Choy A, Remak E, et al. Cost-consequence analysis of adjunctive use of the COX-2 inhibitor parecoxib compared to opioids alone after non-cardiac surgery in the United Kingdom. Gazz Med Ital Arch Sci Med. 2013;172:835–844. | ||

Nong L, Sun Y, Tian Y, Li H, Li H. Effects of parecoxib on morphine analgesia after gynecology tumor operation: a randomized trial of parecoxib used in postsurgical pain management. J Surg Res. 2013;183(2):821–826. | ||

Malan TP Jr, Gordon S, Hubbard R, Snabes M. The cyclooxygenase-2-specific inhibitor parecoxib sodium is as effective as 12 mg of morphine administered intramuscularly for treating pain after gynecologic laparotomy surgery. Anesth Analg. 2005;100(2):454–460. | ||

Snabes MC, Jakimiuk AJ, Kotarski J, Katz TK, Brown MT, Verburg KM. Parecoxib sodium administered over several days reduces pain after gynecologic surgery via laparotomy. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19(6):448–455. | ||

Tang J, Li S, White PF, et al. Effect of parecoxib, a novel intravenous cyclooxygenase type-2 inhibitor, on the postoperative opioid requirement and quality of pain control. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(6):1305–1309. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.