Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 14

Effects of Leader-Follower Extraversion Congruence and Sectoral Difference on Leader-Member Exchange: A Cross-Sectional Study

Authors Chen Q, Yang S, Li M, He J, Lu L

Received 3 July 2021

Accepted for publication 1 October 2021

Published 6 November 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 1833—1846

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S327759

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Qishan Chen,1,*,2 Shuting Yang,3,* Miaosi Li,3 Jingyi He,1,2 Liuying Lu1,2

1Key Laboratory of Brain, Cognition and Education Sciences, Ministry of Education, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Psychology, Center for Studies of Psychological Application, and Guangdong Key Laboratory of Mental Health and Cognitive Science, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China; 3Beijing Key Laboratory of Applied Experimental Psychology, National Demonstration Center for Experimental Psychology Education (Beijing Normal University), Faculty of Psychology, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Qishan Chen Email [email protected]

Purpose: Drawing upon self-categorization theory and the comparative literature on public and private sectors, the purpose of this study is to examine whether leader-follower extraversion congruence is positively related to leader-member exchange (LMX) and whether congruence at high levels of extraversion results in higher LMX than congruence at low levels. Furthermore, the study aims to investigate the moderating role of sectoral difference in the relationship between extraversion fit and LMX.

Methods: Participants were 320 leader-follower dyads (53 leaders and 320 followers) from various public and private sectors in the Chinese cultural context. The extraversion part of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and leader-member exchange multidimensional measure (LMX-MDM) were used to measure extraversion and LMX, respectively. Hypotheses were tested using cross-level moderated polynomial regression and response surface analysis.

Results: Leader-follower extraversion congruence was not significantly associated with LMX, and there was no significant difference in LMX between congruence at high levels of extraversion and congruence at low levels. However, sectoral difference moderated the relationship between extraversion fit and LMX. Specifically, in the public sector, leader-follower extraversion congruence was positively related to LMX, and LMX was higher when leader and follower extraversion were both at a high level compared to when they were at a low level. In the private sector, this fit effect vanished.

Practical Implications: The results suggest that, in the public sector, when organizations deal with the deployment of staff, taking leader-follower extraversion fit into account may mitigate possible later relationship conflicts. However, in the private sector, by not emphasizing extraversion fit, organizations can focus resources on more crucial factors.

Originality/Value: By considering sectoral difference as the boundary condition of leader-follower extraversion fit, this study extends the comparative literature on public and private sectors and supports self-categorization theory.

Keywords: leader-member exchange, leader-follower extraversion, sectoral difference, self-categorization theory

Introduction

In interpersonal interactions, people are always curious about whether extraverts will build better relationships with other extraverts or will engage in more complementary interactions with introverts. Extraversion in organizational behavior has always been recognized as an important feature of effective leaders.1,2 In the past, most studies focused on the advantages of extraverted leaders in examining the effectiveness of leadership and management.1,3–5 Those studies gave little attention to the effect of the interaction of leaders’ and followers’ extraversion on organizational behavior and the relationships between leaders and followers. Given that extraversion plays a key role in interpersonal behavior patterns,6 considering only leaders’ extraversion is not enough when investigating the exchange process of leaders and followers. It is necessary to consider the extraversion of leaders and their followers at the same time. Therefore, the present research attempts to explore the effect of followers’ and leaders’ extraversion congruence on the quality of their relationship.

Previous results of studies on the effect of leader and follower extraversion congruence were inconsistent. Leader-follower extraversion fit is a form of person-environment fit. Some studies support that leader-follower extraversion fit is a supplementary fit,7–9 such that the more congruent a leader and follower’s extraversion levels, the better matched they are. A similarity in extraversion levels between leaders and followers has a positive effect on followers’ perception of leader-member exchange (LMX).7 When leaders and followers match on level of extraversion, they tend to consider one another in-group members and bear a stronger sense of intimacy and positive emotional expressions and behaviors, in turn, showing high-level LMX.7,10,11

At the same time, many research results still do not support this extraversion congruence effect.12–15 Some studies that examined the relationship of leader-follower extraversion similarity with perception of LMX and performance ratings found no significant results.12,13 In addition, there are few results supporting complementary fit.14,15

Although the results are inconsistent, only a small number of studies have tested for moderating variables of leader-follower extraversion fit, such as collectivism,16 familiarity,13 liking,13 power14 and power distance orientation.9 No one has investigated other key boundary conditions such as organizational attribute, organizational climate, and so on. In a meta-analysis on person-environment fit at work, Kristof‐Brown et al17 pointed out that sampling strategy/sample characteristics pose an important moderator of the relationship between personality congruence fit and followers’ attitudes or contextual performance. Fit is more influential in some organizations than others,17,18 because the self-identification process varies with the characteristics of the environment as well as the social background, motivation and values of workers. Differences between employees from the public and private sectors have drawn much attention. These differences are crucial and prominent, especially in China. On the one hand, traditional Chinese culture advocates collectivism.19 Along with rapid economic development and fierce market competition in China, sociocultural values have changed, and individualism has appeared,20 especially in the private sector. On the other hand, the Chinese public sector often entails personnel management, including the establishment of posts. This is termed the bianzhi system, and it results in employees from the public sector more often holding permanent jobs for life in comparison to employees from the private sector.21 Workers in the private sector receive greater financial rewards than those in the public sector.22–26 People in the public sector value personal relations, friendliness, and congenial colleagues more, whereas people in the private sector attach more importance to economically oriented associates.27 These differences in motivation and values between individuals in public and private sectors may have diverse impacts on the mechanism of the leader-follower relationship. Thus, we propose sectoral difference (public vs private) as a moderator between leader and follower extraversion congruence and LMX.

Regarding the effect of leader and follower extraversion congruence on LMX, there are a number of inconsistent research results. The main purpose of the present research is to investigate the follower and leader extraversion congruence effect and its boundary condition, sectoral difference. Specifically, we hypothesize that leader-follower extraversion congruence is positively related to LMX and that LMX is higher when leader-follower congruence is at high levels of extraversion than when leader-follower congruence is at low levels. We also hypothesize that sectoral difference moderates the relationship between extraversion congruence and LMX and that this relationship is stronger in the public sector than in the private sector. The hypothesized model for this study is shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 The conceptual model. |

There are three potential contributions of the current study. First, this study contributes to the LMX literature by illustrating and elaborating the relation between leader-follower extraversion and LMX. Second, this research contributes to the area of leader-follower extraversion fit, because we assume that leader-follower extraversion fit is a supplemental fit, and we consider sectoral differences as a boundary condition of this fit. Third, by comparing leader-follower extraversion fit in different environments of the public and private sectors, this research extends previous comparative literature of public and private sectors. The present study also makes practical contributions to human resource management (HRM). Public sectors could benefit from matching leaders with followers on extraversion personality when organizations manage the recruitment and deployment of staff. In the private sector, leader-follower extraversion fit does little to improve the quality of leader-follower relationships.

Leader-Follower Extraversion Congruence and LMX

With regard to dyadic relationships in the person-environment fit literature, the match between leaders and followers has attracted much attention.17,28 Prior studies have investigated not only matching demographic variables at the surface level (e.g.,29,30) but also matching at a deep level, including value congruence (e.g.,31), goal congruence (e.g.,32), attitude congruence (e.g.,33), and personality congruence (e.g.,34,35). The present research focuses on the match in extraversion between leaders and followers.

Extraversion and introversion are two distinct personality characteristics. They differ in susceptibility to stress, resting level of cortical arousal, social interaction, and many other aspects.36 Introverts are more reserved, quiet and socially aloof.37 The core of extraversion is sociability; extraverted individuals tend to be sociable, gregarious, positive, assertive and active.14

As a dimension of the Big Five personality traits, extraversion is an important personality trait that is related to interpersonal interaction because this trait can unconsciously affect behaviors and attributions when people contact others.14,38 Many researchers have proven that both leaders’ and followers’ extraversion levels affect the interaction between them (e.g.,14,33,39). When leaders and followers have similar extraversion levels, they are more likely to build positive relationships.12

LMX refers to the dyadic relationship between leaders and followers.40 Leaders develop dyadic relationships with their followers that vary from high quality to low quality; these are also classified as “in-group” and “out-group” relationships. The LMX development model suggests that both leader and follower characteristics, including personality, may have a strong influence on initial interactions and even on the whole development process of LMX.41 Therefore, when leaders and followers come into contact, the categorization and identification process based on extraversion fit can pave the way for a high-quality dyadic relationship between them. Self-categorization theory11,42 proposes that individuals in a group tend to perceive cognitive similarities and differences in others according to certain characteristics and categorize themselves. They consider people who are quite similar to themselves as in-group members, while the rest are perceived as out-group members. Typically, differences between in-group members become minimized, whereas gaps with out-group members become expanded in their minds. The process of self-categorization can help individuals achieve self-affirmation and promote interpersonal interactions.42 According to self-categorization theory, when a leader and follower are similar in terms of extraversion, they are more likely to regard each other as in-group members in search of a stronger sense of intimacy and identity. This process relates to more optimistic attitudes, cooperation and empathy between leaders and followers, which can prompt a high quality of leader-follower exchange.28,42

When leaders and followers have congruent extraversion levels, their relationship can develop better. When leaders and followers have similarly high levels of extraversion, a pleasant and energetic relationship more easily develops between them.12 It is more likely that extraverted individuals – both leaders and followers – will consider other extraverts to be in-group members based on self-categorization theory. This process can help people achieve self-affirmation.42 Specifically, if followers high in extraversion observe that their leaders, usually their behavior model, also behave as actively and livelily as themselves, they will recognize that those behaviors are suitable and even admirable. Moreover, in the organizational environment, both proactive leaders and followers prefer partners who can provide them with proactive feedback and support.35 The interaction between energetic leaders and followers is similar to a mutual reinforcement process that benefits their quality of exchanges.

Harmonious relationships can also be built when both leaders and followers are introverted. When employees work with leaders who resemble themselves with regard to introversion, they can further affirm that their quiet behaviors and introspective characteristics are also acceptable. With similar levels of introversion, followers and leaders can ease themselves into effective communication. There is more empathy and understanding between introverted leaders and followers; thus, they are able to find a comfortable way to communicate and work together. During this process, both introverted parties can maintain a suitable state of arousal by avoiding uncomfortable socializing and focusing on work tasks,36 which can contribute to the development of exchange between them.

Aside from the benefits of extraversion congruence mentioned above, extraverted dyads of leaders and followers have some advantages over introverted dyads. Extraverted leaders and followers may have more chances to develop a deep relation, because extraverts are inclined to interact actively with others and are eager to receive inspiring feedback from people around them.37,43 In contrast, introverts are more likely to remain and work alone as well as distance themselves from arousal and potential tension due to social contact. Even though introverted leaders and followers can find a suitable means of communicating and cooperating to reduce energy consumption, the natural characteristics of introverts make their relationships comparatively less enjoyable or pleasant than those of extraverted dyads.37

In contrast to congruent dyads, people with incongruent styles cannot effectively integrate themselves well.44 On the one hand, extraverted leaders are apt to express their forceful emotions and energy, while introverted followers are sensitive to intense reactions from their leaders.37,45 Being susceptible to heavy environmental stress, introverted followers maintain their energy by thinking and working alone to avoid frequent contact with their leaders.43 When dealing with such interactions with their leader, introverted followers’ arousal level increases excessively, and they are less likely to perform in a manner that will satisfy their extraverted leaders. Those quiet and unenergetic followers may not only gradually disappoint their leaders, but they may also sink into fatigue and self-accusation. As a result, a vicious circle develops within their relationship.

On the other hand, extraverted followers require much social support through socialization to maintain their energetic state.43 Because introverted leaders are relatively introspective, extraverted followers may suffer setbacks when they seek daily social support from their leaders. Furthermore, introverts are more sensitive to disagreeable behaviors because these behaviors create more relationship problems for them.45 There are more opportunities for introverted leaders to notice disagreements with extraverted followers, which may decrease the quality of their exchanges. Hence, in both of these cases of extraversion incongruence, the relationship between leaders and followers may be hurt.

Based on the above arguments, we propose that the quality of leader-follower exchanges varies with forms of leader-follower extraversion congruence. We hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1a: The congruence of leader extraversion and follower extraversion is positively related to LMX.

Hypothesis 1b: LMX is higher when leader and follower extraversion are both at a high level compared to when leader and follower extraversion are both at a low level.

Moderating Role of Sectoral Difference

Different goals and motives among the public and private sectors mean differently activated readiness for a given category, which may result in distinct self-categorization processes among leaders and followers. Self-categorization theory11 notes that the interaction between accessibility of categorization and fit determines the self-categorization process. Accessibility of categorization is the relative readiness of a given category to become activated.46,47 The more accessible a given category is, the more easily a stimulus can invoke the relevant categorization. Among various fits based on similarities, a more accessible category will become salient. The more accessible the category is, the more likely relative categorization forms are. Meanwhile, other less accessible categories will be masked. Group members’ goals and motives are major determinants of accessibility.11 With different motives, the value significance of different characteristic categorizations varies. Accordingly, for the public sector and private sector, different motives bring different accessibility of categorization, which may influence the salience of social categorizations and group memberships in their social perception. Therefore, we propose that different leader-follower categorization processes exist in public and private sectors, which would alter their relationship quality as a result.

Many studies use basic definitions to distinguish between public and private sector. Most such distinctions focus on funding, ownership and governance modes.22 Public sector organizations are funded and owned by the government or the public, while private sector organizations are owned privately and guided by the market in terms of profit.22 A crucial characteristic distinguishing public and private sector organizations is the profit direction, which results in a different focus. The financial resources of private sectors depend on economic markets.48 Private sector organizations sell products or services to customers in the market to create wealth for shareholders; thus, private enterprises consider their market and customer demands as their number one priority. In contrast, public sector organizations are less restricted by the intention of making a profit.48 The public sector has more conflicting values and multiple competing goals compared to the private sector, because private sector organization goals can be evaluated simply by means of economic outcomes.48,49 In addition, because of these different goals, the organizational environment and HRM are distinct between private and public sector organizations. Directed by profit, private enterprises part ways with incompetent employees or recruit new capable people. As a result, private sector organizations have higher staff mobility than do public sector organizations.23 Comparatively, public sector organizations have lower levels of staff turnover in China. Many employees of public servant hold a permanent job for life because of the personnel system, named the bianzhi system in China.50 In the Chinese public sector, the average pay is not high, and the variance in pay is smaller than that of private enterprises.21 Moreover, many jobs in public sectors are stable, and the tasks are repetitive.21

Relatedly, it is difficult for leaders and followers to process categorization based on personality fit in private enterprises because in the private sector extrinsic rewards are popular and prominent.49 Groups and their members spare no effort to provide services and products to satisfy the market for profit. Social exchange theory suggests that social interaction between leaders and followers is the process of exchanging material resources and nonmaterial resources.51,52 Because of the norm of reciprocity and the preference of neighboring in social exchange, if a leader provides followers with material resources or awards, followers are more willing to improve their task performance to arrive at material goals in the private sector.51 In the private sector, both leaders and followers focus on exchange relationships based on material resources.23 Compared with extrinsic rewards, other nonmaterial exchanges, such as identification based on personality fit, are not accessible and important for individuals in private enterprises. In private enterprises, as long as leaders and followers can successfully complete their mission, they can achieve positive feedback from financial returns and others’ appraisals. In turn, the exchange relationship between leaders and followers is successful in private enterprises. Therefore, in the private sector, the quality of the exchange relationship between leaders and followers relies more on the social exchange of material resources than on social identity based on personality fit. In contrast, extraversion congruence between leaders and followers may affect the social identity process more so in the public sector due to the greater accessibility of this categorization. Congenial association as intrinsic reinforcement can mean a great deal for public sector members.27 Many studies support the notion that individuals in the public sector are motivated more by intrinsic rewards and less by extrinsic factors than private sector employees.23,53 Merit pay cannot motivate Chinese public servants to a great extent because public sector pay levels are on average higher than those in the private sector.21 Staff in the public sector tend to be attracted by a supportive environment and harmonious relationships that can benefit from similar styles and extraversion congruence.23 Moreover, workers in the public sector have less mobility and higher job security in China.50,54 Therefore, at this time, categorization based on similar characteristics may be of greater importance for staff who, in comparison, will work with each other for a longer time.

Therefore, those distinctions suggest different effects of leader-follower congruence depending on the context of public or private sector. Compared with the private sector, extraversion congruence between leaders and followers may more heavily affect the social identity process in the public sector, because the public sector places more emphasis on nonmaterial resources and less emphasis on material resources than the private sector. First, in the public sector, when leaders and followers have similar levels of extraversion, they are more likely to categorize themselves based on extraversion level and form a corresponding identification (nonmaterial exchange). This categorization process can promote LMX in the public sector. In contrast, in the private sector, LMX is more likely to be affected by material resource exchange and is less likely to be influenced by nonmaterial resource exchange, i.e., extraversion fit. Second, in the public sector, extraverted leaders and followers can develop better relationships than introverted leaders and followers because of the sociability of extraverts.37 However, the advantages of extraverted leaders and followers may be diminished in the private sector, because the primary focus of the private sector is economic benefits rather than social interaction.

Hence, we suggest sectoral difference moderation hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2: Sectoral difference will moderate the relationship of leader and follower extraversion congruence with LMX.

Hypothesis 2a: Specifically, the relationship of leader and follower extraversion congruence with LMX is stronger in the public sector than in the private sector.

Hypothesis 2b: For the public sector, LMX is higher when leader and follower extraversion are both at a high level compared to when leader and follower extraversion are both at a low level. However, for the private sector, this difference in LMX under these two situations is smaller.

Method

Participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted from December 2017 through April 2018 in China. Participants were recruited randomly from public institutions (schools and hospitals), state-owned enterprises (aviation, postal service, and construction), government agencies (agriculture, forestry, and traffic), and private enterprises (education, foreign trade, finance, medicine, insurance, manufacturing, and internet). With the help of corresponding human resources departments, we distributed questionnaires to leaders (the heads of the obstetrics and gynecology department and psychiatry department in hospitals, the heads of teaching and research sections in schools, the section chiefs in government agencies and the team heads in private enterprises) and their direct supervisees/followers on the spot and then collected questionnaires by group, with each group having an independent code to match the data. The questionnaires of followers included items pertaining to extraversion, demographics, and LMX, while the questionnaires of leaders only included extraversion and demographic parts.

The original sample consisted of 63 groups, with 586 questionnaires were distributed. Of those, 528 questionnaires were received. After eliminating questionnaires with high numbers of missing responses, groups with fewer than 3 members, or employees with more than one direct leader, the final sample included 53 groups (53 leaders and 320 followers), yielding a 63.65% response rate. There were an average 6.04 followers per group leader (min = 2, max = 23, SD = 4.92). Among all of the followers, 130 were male, and the average age was 31.47 (SD = 8.98). In terms of their educational background, 2.19% had a middle school degree or below, 26.25% had a high school degree, 21.25% had a junior college degree, 40.00% had an undergraduate degree, and 5.31% had a master’s degree or above. Of the 53 leaders, 31 were male; the average age was 39.68 (SD = 8.27); 1.89% had a middle school degree or below, 13.21% had a high school degree, 26.42% had a junior college degree, 41.51% had an undergraduate degree, and 13.21% had a master’s degree or above.

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of South China Normal University (SCNU-PSY-335). Written informed consent was collected from all participants. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

Extraversion

Leader and follower extraversion were both measured using the extraversion portion of the NEO-PI-R.55 Leaders and followers indicated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with statements about themselves on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The reliability coefficient of follower extraversion was 0.91, while that of leader extraversion was 0.93.

Leader-Member Exchange (LMX)

Followers rated the quality of their relationship with their direct leader using the LMX-MDM56 along a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The reliability coefficient was 0.92.

Sectoral Difference

For sectoral difference, we created a categorical variable, where “1” represented the “public sector” and “0” represented the “private sector.” In the final sample, the public sector included public institutions, state-owned enterprises, and government agencies. The private sector included private enterprises in China. The final sample consisted of 26 groups (26 leaders and 169 followers) from the public sector and 27 groups (27 leaders and 151 followers) from the private sector.

Control Variables

Previous studies on leader-follower personality fit controlled for age, education, and gender dissimilarity to examine hypotheses.35,57 The age, education, and gender dissimilarity of leaders and followers are correlated with LMX.57 Therefore, in the analysis, we controlled for age, education, and gender dissimilarity.

Analytical Approach

SPSS 21.0 was used to conduct descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and reliability analysis. Mplus 8.3 was used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis and polynomial regression analysis.

Hypotheses 1a-1b were tested using cross-level polynomial regression.58 The independent variables (leader extraversion and follower extraversion) were scale-centered by subtracting the midpoint of the scale to decrease multicollinearity.59

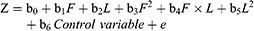

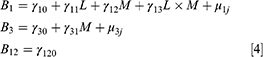

We created a polynomial regression model according to the following equations:

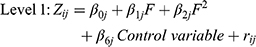

Because there was nonindependence among followers of the same leader, it was necessary to combine polynomial regression and hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) in our analyses.58 The polynomial regression equation via HLM was as follows:

γ00, γ10, γ01, γ20, γ11, γ02 and γ60 in Equation [2] are equal to b0, b1, b2, b3, b4, b5, and b6 in Equation [1].

First, if the curvature of the incongruence line (b3-b4+b5) is significantly negative, which means that the surface is curved downward along the incongruence line, then the congruence hypothesis, i.e., Hypothesis 1a, would be supported.

For Hypothesis 1b, if the slope of the congruence line (b1+b2) is significantly positive, the hypothesis is supported. However, if the slope of the congruence line (b1+b2) is significantly negative, then LMX is higher when the extraversion of the leader and follower are both at a low level compared to when it is at a high level.

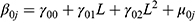

We tested Hypothesis 2 using cross-level moderated polynomial regression.60 Based on the original polynomial terms in equation [1], we added the moderator variable (M) and the interaction of the moderating variable with each of the original polynomial terms ( ). The equation for the moderated polynomial regression is as follows:

). The equation for the moderated polynomial regression is as follows:

Sectoral difference, a moderator variable, represents a group-level variable; therefore, we added it to the equations at level 2. The moderated polynomial regression via HLM is shown below:

B0, B1, B2, B3, B4, B5, B6, B7, B8, B9, B10, B11 and B12 in Equation [3] are equal to γ00, γ10, γ01, γ30, γ11, γ02, γ03, γ12, γ04, γ31, γ13, γ05 and γ120 in Equation [4].

Hypotheses 2 and 2a are supported if including the moderation interaction terms, the model fit improves.60 Moreover, there is a need for the public sector the curvature of the incongruence line would be significantly negative, while the curvature of the incongruence line for the private sector would be less so. Hypothesis 2b would be supported if the slope of the congruence line is significantly positive for the public sector and the slope of the congruence line is less significant for the private sector than for the public sector.60

Results

Preliminary Analyses

To control for common method variance, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis to examine the discriminant validity of the two follower self-reported variables (extraversion and LMX). The results indicated that the two-factor model showed a good fit (χ2/df = 2.73, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05), one that was much better than the single-factor model (χ2/df = 16.28, CFI = 0.60, TLI = 0.49, RMSEA = 0.22, SRMR = 0.14). Thus, common method variance was not a serious threat to our data. The results suggest that the scales applied here measure different constructs and that they could be applied in further analyses.

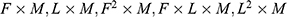

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables are presented in Table 1. Gender dissimilarity, age dissimilarity and education dissimilarity were not significantly related to LMX. LMX was significantly related to sectoral difference (r = −0.25, p < 0.01) and follower extraversion (r = 0.30, p < 0.01).

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations |

Leader-Follower Extraversion Congruence and LMX

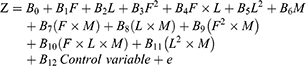

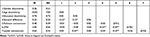

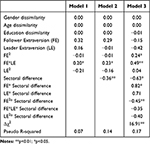

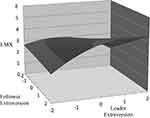

The results are reported in Tables 2 and 3. The curvature of the incongruence line was not significant (curvature = −0.42, SE = 0.27, p > 0.05, 95% CI [−0.94, 0.11]). Moreover, the slope of the congruence line was not significant (slope = 0.47, SE = 0.48, p > 0.05, 95% CI [−0.47, 1.41]). Therefore, neither Hypothesis 1a nor Hypothesis 1b was supported. Leader-follower extraversion congruence was not significantly related to LMX, and there was no significant difference in LMX between congruence at high levels of extraversion and congruence at low levels. However, the surface plot (see Figure 2) showed a weak tendency to support Hypothesis 1a and Hypothesis 1b.

|

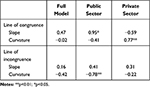

Table 2 Cross-Level Polynomial Regression of LMX and Follower and Leader Extraversion Congruence with Sectoral Difference Moderation |

|

Table 3 Response Surface Tests of Follower and Leader Extraversion Congruence on LMX with Sectoral Difference Moderation |

|

Figure 2 Estimated surface relating follower and leader extraversion with LMX. |

Moderating Role of Sectoral Difference

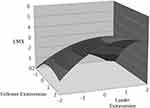

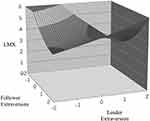

Next, for the public sector, the curvature of the incongruence line was significantly negative (curvature = −0.78, SE = 0.23, p < 0.01, 95% CI [−1.24, −0.32]). The intercept of the first principle was not different from 0 (95% CI [−4.75, 3.10]); the slope of the first principle axis was not different from 1 (95% CI [−1.72, 3.05]). In the private sector, the curvature of the incongruence line (curvature = −0.22, SE = 0.28, p > 0.05, 95% CI [−0.77, 0.33]) was not significant. Finally, the inclusion of the moderating interaction terms significantly improved the model (Δχ2 = 16.91, p < 0.01). Therefore, Hypotheses 2 and 2a were supported. Sectoral difference moderated the relationship of leader and follower extraversion congruence with LMX. Leader-follower extraversion congruence was positively related to LMX in the public sector, while this relationship was not significant in the private sector.

In the public sector, the slope of the congruence line was significantly positive (slope = 0.95, SE = 0.43, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.11, 1.80]), whereas the slope of the congruence line was not significant in the private sector (slope = −0.59, SE = 0.52, p > 0.05, 95% CI [−1.61, 0.44]), thus supporting Hypothesis 2b. In the public sector, LMX was higher when leader and follower extraversion were both at a high level compared to when leader and follower extraversion were both at a low level, but this relationship was not significant in the private sector.

Figure 3 shows that, for the public sector, LMX increased when leaders and followers had congruent levels of extraversion. Moreover, the surface plot shows that LMX more sharply increased when leader and follower extraversion were both at a high level as opposed to both at a low level. Figure 4 illustrates the response surface for the private sector.

|

Figure 3 Estimated surface relating follower and leader extraversion with LMX in the public sector. |

|

Figure 4 Estimated surface relating follower and leader extraversion with LMX in the private sector. |

Discussion

Prior researchers held different attitudes on leader-follower extraversion fit and obtained inconsistent results.9,10,12,15 Few studies have considered situational factors as the boundary condition of leader-follower extraversion fit. In the present study, we examined the relationship between leader-follower extraversion fit and LMX and found nonsignificant results based on our entire sample. Hypothesis 1a and 1b were not supported. Similar to our findings, many previous studies on object fit of leader-follower extraversion also achieved nonsignificant results.12,13 However, many previous studies have shown that leader-follower extraversion fit is a supplementary fit.7,8 The reason why the main effects of leader-follower extraversion congruence on LMX may have been nonsignificant was that the relationship was potentially moderated by an unobserved variable. We further investigated the moderating effect of sectoral difference on the relationship between leader-follower extraversion fit and LMX. We found that the effect of leader-follower supplementary fit around extraversion was evident in the public sector but was not significant in the private sector. Hypothesis 2 and 2a were thus supported. These results can be explained by self-categorization theory, which posits discrepant categorization under comparative environments,11 and the comparative literature on the public and private sectors. Furthermore, we found that leaders and followers with high congruent extraversion had higher LMX quality than did those with low congruent extraversion in the public sector, while this effect was not significant in the private sector, thus supporting Hypothesis 2b.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

First, these results contribute to the area of leader-follower extraversion fit, which is a type of person-environment fit. Our results partly support the idea that leader-follower fit is a supplemental fit rather than a complementary fit. Similarity in extraversion between leaders and followers can bring the self-categorization process to an in-group member, which benefits their interaction. Moreover, by examining sectoral difference as a moderator variable, we identified a boundary condition of leader-follower extraversion fit. Prior arguments and practical results on leader-follower extraversion fit differ, but few studies have evaluated the moderating effect at the individual level.8,10,12,15 Inconsistent results may have also occurred due to different characterizations of situational conditions, which need to be considered with respect to leader-follower extraversion fit. This study provides an empirical demonstration that leader-follower extraversion fit may vary by group.

Second, this study contributes to the LMX literature by emphasizing extraversion fit as an antecedent variable to LMX. Our findings support that the interaction of leader and follower extraversion has great significance for the quality of LMX in some environments. Specifically, the extraversion congruence between them is able to enhance the development of relationships in the public sector. Moreover, our study thoroughly investigated the congruence condition, concluding that high extraversion congruence in dyads results in better LMX than does high introversion congruence in dyads, because the nature of extraverted leaders and followers and their preference for positive, social interactions can alleviate barriers of communication and exchange between them.43 In previous studies on LMX, an extraverted leader was mostly known as a critical factor, as relates to leadership and LMX.1,40 Therefore, the results of this study help to illustrate the complicated nature of the relation between extraversion and LMX.

Finally, this study also extends the comparative literature on the public and private sectors by comparing different effects of extraversion on the relationship between leaders and followers. Most previous studies focused on a macroscopic comparison of the public and private sectors, such as structure, earnings and HRM.48,54 With regard to microscopic comparisons, few studies have investigated person-environment fit, except for employee-organization value congruence.53,61 The present research provides the first empirical support that employee and leader personality fit (extraversion congruence) is more crucial for the quality of relationships in the public sector than in the private sector. This difference may be due to different focuses on intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. Public sector organizations place more weight on intrinsic rewards, and private sector organizations place more weight on extrinsic rewards.22,26 In the public sector, the exchange of intrinsic rewards (i.e., identification based on extraversion fit) is crucial for leaders and followers. They are less likely to be attracted by extrinsic factors than are private sector employees.23 Thus, leader-follower extraversion fit, which is important in the public sector, can affect the quality of the relationship between leaders and followers. In the private sector, exchanges based on material resources are vital for leaders and followers under the goal of the pursuit of maximum economic benefits.23 Compared with extrinsic rewards, other nonmaterial exchanges, e.g., categorization and identification based on extraversion fit, are not as accessible and important for individuals in private enterprises. The result is a nonsignificant effect of leader-follower extraversion congruence.

Concerning practical contributions, the present research has several implications for increasing the efficiency of HRM. Our research suggests that, when organizations manage the deployment of leaders and followers, they should consider personality fit. During the recruitment process, organizations can select individuals who are more likely to adapt to the group in consideration of the characteristics of the organization and group members. Moreover, in building a team and transferring personnel, managers can consider the personality congruence effect between leaders and followers. Specifically, for public sectors, organizations can put leaders and followers who share similar personalities together, i.e., both are extraverts or introverts. Taking leader-follower extraversion fit into account ahead of time may mitigate possible later relationship conflicts in the public sector. However, in the private sector, by leaving out extraversion fit as a primary consideration, a manager can focus on more crucial factors. Additionally, our study provides insight for dealing with situations in which lack of fit between a leader and follower in the public sector based on extraversion has already appeared to hinder the development of LMX. Public sector organizations should learn lessons from the private sector, because private sectors are immune to the detrimental effect of leader-follower extraversion lack of fit. Workers in the private sector attach too much attention to task-based rewards to be affected by personality differences. Therefore, if the public sector can create an atmosphere similar to the private sector, in which extrinsic rewards feature more prominently, the relationship conflict that extraversion incongruence generates may thus be mitigated. Finally, our findings also have practical implications for individuals. Drawing upon our results, in the private sector, followers’ introversion pairing with their leaders, whether or not they are extraverts, does not affect their relationship. In the public sector, when introverted followers work with introverted leaders, those followers find a more advantageous scenario than do their colleagues high in extraversion.

Limitations and Future Research

The present study has several limitations that need to be considered in future studies. First, despite our findings noting that leader-follower extraversion fit is a supplemental fit and that it supports self-categorization theory, we did not directly test these theoretical assumptions. We assume that both leaders and followers at the same level of extraversion are inclined to identify one another as in-group members for self-enhancement.42 Therefore, future practical studies can directly test the theoretical mechanism as mediators behind leader-follower extraversion fit and LMX. For example, they might examine identity and self-esteem, based on self-categorization theory.11

Second, our research only focused on a comparison of leader-follower personality (extraversion) fit between the public sector and private sector. Although we assumed that this fit difference arises from a distinct identification process based on differences in motivation and value weight, we did not examine radical difference mechanisms of leader-follower extraversion fit or other core aspects of person-environment fit between public and private sector organizations. Private sector and public sector differences are very notable with regard to employment and policies in China. Specifically, employees in the private sector decide to switch jobs more frequently than do employees in the public sector.23 The person-environment fit may differ from the public to the private sector. For example, prior works have noted that, compared with the private sector, employee-organization value congruence on public service motivation is crucial for the public sector and can be helpful for retaining staff.53,62 Therefore, in the future, researchers can consider comparing other types of person-environment fit in the public sector with the private sector and examine radical mechanisms behind fit differences.

Finally, the data were collected all at the same time. Even though extraversion as a natural personality is stable to the point that it does not change over time, regardless of how many times it is measured,63 we cannot assert the causality that extraversion congruence directly leads to a higher quality of LMX. Future research should employ a longitudinal design to examine whether the development of LMX is affected by leader-follower extraversion congruence. In addition, with regard to the sample, all participants in this study came from China. Some special characteristics of the Chinese public sector make the generalizability of the results difficult.35 For example, the Chinese public sector has established posts within the bianzhi system, which means a permanent job for life.21 Staff in the public sector stay with each other for so long that congruence fit as intrinsic reinforcement plays an important role for public sector members.27 Under this circumstance, comparison of the public and private sectors may be more prominent in China. Future research could compare a Chinese sample with a sample from other countries to investigate fit differences between the public and private sectors in different countries.

Conclusions

By examining leader-follower extraversion fit, this study supported self-categorization theory and extended the comparative literature on the public and private sectors. We demonstrated the boundary condition on relationships between leader-follower extraversion fit and LMX. In the public sector, leader-follower extraversion fit is a supplementary fit, while in the private sector, the effect of this fit is diminished.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. QC and SY contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

Funding

This research was funded by the 13th Five-Year Plan Research Project of Philosophy and Social Science in Guangdong, China (GD17XXL02).

Disclosure

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

1. Judge TA, Bono JE, Remus I, Gerhardt MW. Personality and leadership: a qualitative and quantitative review. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(4):765–780. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.765

2. Spark A, Stansmore T, O’Connor P. The failure of introverts to emerge as leaders: the role of forecasted affect. Pers Individ Dif. 2018;121:84–88. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.026

3. Bono JE, Judge TA. Personality and transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89(5):901–910. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.901

4. Grant AM, Gino F, Hofmann DA. Reversing the extraverted leadership advantage: the role of employee proactivity. Acad Manage J. 2011;54(3):528–550. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.61968043

5. Ployhart RE, Lim BC, Chan KY. Exploring relations between typical and maximum performance ratings and the five factor model of personality. Pers Psychol. 2010;54(4):809–843. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00233.x

6. Coté S, Moskowitz DS. On the dynamic covariation between interpersonal behavior and affect: prediction from neuroticism, extraversion, and agreeableness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75(4):1032–1046. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.1032

7. Bernerth J. Putting Exchange Back into Leader-Member Exchange (LMX): An Empirical Assessment of a Social Exchange (LMSX) Scale and an Investigation of Personality as an Antecedent [Dissertation]. Alabama: Auburn University; 2005.

8. Peng J, Wang Z, Hou N. Do leaders and followers see eye to eye? Leader-follower fit in the workplace. Adv in Psychol Sci. 2019;27(2):370–380. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2019.00370

9. Dust S, Wang P, Rode J, Wu Z, Wu X. The effect of leader and follower extraversion on leader-member exchange: an interpersonal perspective incorporating power distance orientation. J Soc Psychol. 2020;1–17. doi:10.1080/00224545.2020.1848774

10. Salminen M, Henttonen P, Ravaja N. The role of personality in dyadic interaction: a psychophysiological study. Int J Psychophysiol. 2016;109:45–50. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.09.014

11. Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford: Blackwell; 1987.

12. Bernerth JB, Armenakis AA, Feild HS, Giles WF, Walker JH. The influence of personality differences between subordinates and supervisors on perceptions of LMX. Group Organ Manag. 2008;33(2):216–240. doi:10.1177/1059601106293858

13. Strauss JP, Barrick MR, Connerley ML. An investigation of personality similarity effects (relational and perceived) on peer and supervisor ratings and the role of familiarity and liking. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2011;74(5):637–657. doi:10.1348/096317901167569

14. Yoon DJ, Bono JE. Hierarchical power and personality in leader-member exchange. J Manag Psychol. 2016;31(7):1198–1213. doi:10.1108/JMP-03-2015-0078

15. Chen L, Wang Z, Luo N, Luo Z. Leader-subordinate extraversion fit and subordinate work engagement: based on dominance complementarity theory. Acta Psychol Sin. 2016;48(6):710–721. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2016.00710

16. Schaubroeck J, Lam SSK. How similarity to peers and supervisor influences organizational advancement in different culture. Acad Manage J. 2002;45(6):1120–1136. doi:10.5465/3069428

17. Kristof‐Brown AL, Zimmerman RD, Johnson EC. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: a meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Pers Psychol. 2005;58(2):281–342. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

18. Chatman JA. Improving interactional organizational research: a model of person-organization fit. Acad Manage Rev. 1989;14(3):333–349. doi:10.5465/amr.1989.4279063

19. Earley PC. East meets west meets mideast: further explorations of collectivistic and individualistic work groups. Acad Manage J. 1993;36(2):319–348. doi:10.5465/256525

20. Huang Z, Jing Y, Yu F, et al. Increasing individualism and decreasing collectivism? Cultural and psychological change around the globe. Adv in Psychol Sci. 2018;26(11):2068–2080. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2018.02068

21. Liu BC, Tang LP. Does the love of money moderate the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction? The case of Chinese professionals in the public sector. Public Adm Rev. 2011;71(5):718–727. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02411.x

22. Baarspul HC, Wilderom CPM. Do employees behave differently in public-vs private-sector organizations? A state-of-the-art review. Public Adm Rev. 2011;13(7):967–1002. doi:10.1080/14719037.2011.589614

23. Buelens M, Van den Broeck H. An analysis of differences in work motivation between public and private sector organizations. Public Adm Rev. 2007;67(1):65–74. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00697.x

24. Bullock JB, Stritch JM, Rainey HG. International comparison of public and private employees’ work motives, attitudes, and perceived rewards. Public Adm Rev. 2015;75(3):479–489. doi:10.1111/puar.12356

25. Houston DJ. Public-service motivation: a multivariate test. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2000;10(4):713–727. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024288

26. Karl KA, Sutton CL. Job values in today’s workforce: a comparison of public and private sector employees. Public Pers Manage. 1998;27(4):515–527. doi:10.1177/009102609802700406

27. Jurkiewicz CL, Massey TK, Brown RG. Motivation in public and private organizations: a comparative study. Publ Prod Manag Rev. 1998;21(3):230–250. doi:10.2307/3380856

28. Derindag OF, Demirtas O, Bayram A. The leader-member exchange (LMX) influence at organizations: the moderating role of person-organization (PO) fit. Revi Bus. 2021;41(2):32–48.

29. Tsui AS, O’Reilly CA. Beyond simple demographic effects: the importance of relational demography in superior-subordinate dyads. Acad Manage J. 1989;32(2):402–423. doi:10.5465/256368

30. Vecchio RP, Bullis RC. Moderators of the influence of supervisor-subordinate similarity on subordinate outcomes. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(5):884–896. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.884

31. Brown ME, Trevino LK. Leader-follower values congruence: are socialized charismatic leaders better able to achieve it? J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(2):478–490. doi:10.1037/a0014069

32. Witt LA. Enhancing organizational goal congruence: a solution to organizational politics. J Appl Psychol. 1998;83(4):666–674. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.83.4.666

33. Phillips AS, Bedeian AG. Leader-follower exchange quality: the role of personal and interpersonal attributes. Acad Manage J. 1994;37(4):990–1001. doi:10.5465/256608

34. Wilson KS, Derue DS, Matta FK, Howe M, Conlon DE. Personality similarity in negotiations: testing the dyadic effects of similarity in interpersonal traits and the use of emotional displays on negotiation outcomes. J Appl Psychol. 2016;101(10):1405–1421. doi:10.1037/apl0000132

35. Zhang Z, Wang M, Shi J. Leader-follower congruence in proactive personality and work outcomes: the mediating role of leader-member exchange. Acad Manage J. 2012;55(1):111–130. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.0865

36. Beauducel A, Brocke B, Leue A. Energetical bases of extraversion: effort, arousal, EEG, and performance. Int J Psychophysiol. 2006;62(2):212–223. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.12.001

37. Watson D, Clark LA. Extraversion and its positive emotional core. In: Johnson JA, Briggs SR, Hogan R, editors. Handbook of Personality Psychology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1997:767–793. doi:10.1016/B978-012134645-4/50030-5

38. Barrick MR, Mount MK. The big five personality dimensions and job performance: a meta‐analysis. Pers Psychol. 1991;44(1):1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x

39. Nahrgang JD, Morgeson FP, Ilies R. The development of leader–member exchanges: exploring how personality and performance influence leader and member relationships over time. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2009;108(2):256–266. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.09.002

40. Graen GB, Uhlbien M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh Q. 1995;6(2):219–247. doi:10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-5

41. Dienesch RM, Liden RC. Leader–member exchange model of leadership: a critique and further development. Acad Manage Rev. 1986;11(3):618–634. doi:10.5465/amr.1986.4306242

42. Hogg MA, Terry DI. Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Acad Manage Rev. 2000;25(1):121–140. doi:10.2307/259266

43. Perry SJ, Dubin DF, Witt LA. The interactive effect of extraversion and extraversion dissimilarity on exhaustion in customer-service employees: a test of the asymmetry hypothesis. Pers Individ Dif. 2010;48(5):634–639. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.12.022

44. Ronen C, William I. Big Five predictors of behavior and perceptions in initial dyadic interactions: personality similarity helps extraverts and introverts, but hurts “disagreeables”. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(4):667–684. doi:10.1037/a0015741

45. Erez A, Schilpzand P, Leavitt K, Woolum A, Judge T. Inherently Relational: interactions between peers’ and individuals’ personalities impact reward giving and appraisal of individual performance. Acad Manage J. 2015;58(6):1761–1784. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.0214

46. Bruner JS. On perceptual readiness. Psychol Rev. 1957;64(2):123–152. doi:10.1037/h0043805

47. Petsko CD, Bodenhausen GV. Multifarious person perception: how social perceivers manage the complexity of intersectional targets. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2020;14(2):e12518. doi:10.1111/spc3.12518

48. Rainey HG, Backoff RW, Levine CH. Comparing public and private organizations. Public Adm Rev. 1976;36(2):233–244. doi:10.2307/975145

49. Solomon EE. Private and public sector managers. An empirical investigation of job characteristics and organizational climate. J Appl Psychol. 1986;71(2):247–259. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.71.2.247

50. Miao Q, Newman A, Sun Y, Xu L. What factors influence the organizational commitment of public sector employees in China? The role of extrinsic, intrinsic and social rewards. Int J of Hum Resour Manag. 2013;24(17):3262–3280. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.770783

51. Chen Q, Kong Y, Niu J, Gao W, Li J, Li M. How leaders’ psychological capital influence their followers’ psychological capital: social exchange or emotional contagion. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1578. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01578

52. Foa EB, Foa UG. Resource theory of social exchange. In: Törnblom K, Kazemi A, editors. Handbook of Social Resource Theory. New York: Springer; 2012:15–32. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4175-5_2

53. Wright BE, Pandey SK. Public service motivation and the assumption of person-organization fit: testing the mediating effect of value congruence. Adm Soc. 2008;40(5):502–521. doi:10.1177/0095399708320187

54. Démurger S, Li S, Yang J. Earnings differentials between the public and private sectors in China: exploring changes for urban local residents in the 2000s. China Econ Rev. 2009;20(3):138–153. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2011.08.007

55. McCrare RR, Costa PT. NEO Inventories for the NEO Personality Inventory-3 (NEO PI-3), NEO Five-Factor Inventory-3 (NEO-FFI-3) and NEO Personality Inventory-Revised (NEO PI-R): Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; 2010.

56. Liden RC, Maslyn JM. Multidimensionafity of leader-member exchange: an empirical assessment through scale development. J Manage. 1998;24(1):43–72. doi:10.1016/S0149-2063(99)80053-1

57. Bauer TN, Green SG. Development of leader-member exchange: a longitudinal test. Acad Manage J. 1996;39(6):1538–1567. doi:10.5465/257068

58. Jansen KJ, Kristof-Brown AL. Marching to the beat of a different drummer: examining the impact of pacing congruence. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2005;97(2):93–105. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.005

59. Edwards JR, Parry ME. On the use of polynomial regression equations as an alternative to difference scores in organizational research. Acad Manage J. 1993;36(6):1577–1613. doi:10.5465/256822

60. Graham KA, Dust SB, Ziegert JC. Supervisor-employee power distance incompatibility, gender similarity, and relationship conflict: a test of interpersonal interaction theory. J Appl Psychol. 2018;103(3):334–346. doi:10.1037/apl0000265

61. Ren T. Sectoral differences in value congruence and job attitudes: the case of nursing home employees. J Bus Ethics. 2013;112(2):213–224. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1242-5

62. Steijn B. Person-environment fit and public service motivation. Int Public Manag J. 2008;11(1):13–27. doi:10.1080/10967490801887863

63. Costa PT, McCrae RR. Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: the NEO Personality Inventory. Psychol Assess. 1992;4(1):5–13. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.5

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.