Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 18

Effectiveness of Vortioxetine in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder in Real-World Clinical Practice in Italy: Results from the RELIEVE Study

Authors De Filippis S, Pugliese A , Christensen MC, Rosso G, Di Nicola M, Simonsen K, Ren H

Received 18 May 2022

Accepted for publication 20 July 2022

Published 9 August 2022 Volume 2022:18 Pages 1665—1677

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S375294

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Sergio De Filippis,1 Anna Pugliese,2 Michael Cronquist Christensen,3 Gianluca Rosso,4,5 Marco Di Nicola,6,7 Kenneth Simonsen,3 Hongye Ren3

1Department of Neuropsychiatry, Villa Von Siebenthal Neuropsychiatric Clinic, Genzano di Roma, Italy; 2Medical Department, Lundbeck Italy S.p.A, Milan, Italy; 3Medical Affairs, H. Lundbeck A/S, Valby, Denmark; 4Department of Neurosciences ‘Rita Levi Montalcini’, University of Turin, Turin, Italy; 5Psychiatric Unit, San Luigi Gonzaga University Hospital of Orbassano, Turin, Italy; 6Department of Psychiatry, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy; 7Department of Neuroscience, Section of Psychiatry, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy

Correspondence: Anna Pugliese, Medical Department, Lundbeck Italy S.p.A, Via Joe Colombo 2, 20121 Milan, Italy, Tel +39 02 677 41724, Fax +39 02 677 41720, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Vortioxetine has demonstrated efficacy in randomized controlled trials and is approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD); however, data are limited concerning its effectiveness when used in routine clinical care. The Real-Life Effectiveness of Vortioxetine in Depression (RELIEVE) study aimed to assess the effectiveness and tolerability of vortioxetine for the treatment of MDD in routine clinical practice in Canada, France, Italy, and the USA. This paper presents findings for the patient cohort in Italy.

Patients and Methods: RELIEVE was a 6-month, international, observational, prospective cohort study in outpatients initiating vortioxetine treatment for MDD in routine care settings at their physician’s discretion (NCT03555136). Patient functioning was assessed using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). Secondary outcomes included depression severity (9-item Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9]), cognitive symptoms (5-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire-Depression [PDQ-D-5]), and quality of life (EuroQol 5-Dimensions 5-Levels questionnaire [EQ-5D-5L]). Changes from baseline to month 6 were assessed using mixed models for repeated measures, adjusted for relevant confounders.

Results: Data are available for 231 patients enrolled in Italy (mean age, 55.5 years; 27% > 65 years). Overall, 69% of patients reported at least one comorbidity, 55% were overweight/obese, and 47% had current anxiety symptoms. Adjusted least-squares mean (standard error) change in SDS score from baseline to week 24 was − 6.6 (0.6) points (P < 0.001). Respective changes in PHQ-9, PDQ-D-5, and EQ-5D-5L scores were − 5.9 (0.5), − 3.6 (0.4), and +0.13 (0.01) points (all P < 0.0001). Adverse events were reported by 29 patients (13%), most commonly nausea (n = 14, 6%). Eleven patients (5%) discontinued treatment due to adverse events.

Conclusion: Clinically relevant and sustained improvements in overall functioning, symptoms of depression, cognitive symptoms, and health-related quality of life were observed in patients with MDD treated with vortioxetine over a period of 6 months in routine care in Italy, including a high proportion of elderly patients.

Keywords: major depressive disorder, vortioxetine, effectiveness, functioning, real-world evidence

Introduction

Depression is a common illness and a leading cause of disability worldwide.1 Depressive disorders accounted for over 520,000 million years lived with disability in Italy in 2015.2 Current estimates suggest that annually depression affects 5.4% of the Italian population aged 15 years or older, with prevalence rising to 11.6% in the elderly (age ≥65 years).3 The prevalence of depression in Italy has further increased since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.4–6 Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a multidimensional condition characterized by a range of emotional, cognitive, and physical symptoms that have a significant impact on psychosocial functioning.7,8 According to the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) treatment guidelines issued in 2016, restoration of psychosocial functioning is an important treatment goal in patients with MDD.9 However, the potential of antidepressant therapies to directly improve functional outcomes has not been extensively evaluated in routine care settings to date.

Vortioxetine is a novel antidepressant with a multimodal mechanism of action.10 It was first licensed by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of adult patients with MDD in 201311 and has been available in Italy since 2016. Vortioxetine acts as an inhibitor of the serotonin transporter as well as modulating the activity of several serotonin receptor subtypes, thus both directly and indirectly influencing a range of neurotransmitter systems relevant to the neurobiology of MDD.10,12 Data from randomized controlled clinical trials show vortioxetine to have broad dose-dependent efficacy across the entire spectrum of symptoms experienced by patients with MDD, including functional impairment, with greatest treatment effects seen at a dosage of 20 mg/day.13–20

Real-world evidence is useful to support the results of regulatory studies in the more diverse patient populations likely to be encountered in routine care settings. However, data on the real-world effectiveness of vortioxetine in patients with MDD in Italy are currently lacking. The Real-Life Effectiveness of Vortioxetine in Depression (RELIEVE) study aimed to assess the effectiveness and tolerability of vortioxetine for the treatment of MDD in routine clinical practice settings in Canada, France, Italy, and the USA. The overall results of this study have been reported previously.21 This paper presents the study findings for the patient cohort enrolled in Italy.

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Participants

RELIEVE was a multinational, observational, prospective cohort study conducted in outpatients initiating vortioxetine for the treatment of MDD at their physician’s discretion (NCT03555136).

The study design has been reported in detail previously.21 In brief, eligible patients were aged ≥18 years and were experiencing a major depressive episode (MDE) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition) criteria.22 Patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, substance-use disorder, or any neurodegenerative disease significantly affecting cognitive function and those considered at significant risk of suicide or who had attempted suicide within the last 6 months were excluded. As this was a real-world study, participating patients were allowed to use other psychotropic drugs as needed during the study period.

Data were collected at routine clinic visits at baseline and after 12 and 24 weeks of vortioxetine treatment. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a critical management plan was implemented that allowed patients to have remote follow-up visits and complete some patient-reported outcome assessments at home if necessary. However, this was not expected to have a significant impact on the study results, as very few patients did not complete their visits or completed their visits remotely (22 patients, ie, 2% of all eligible patients enrolled in the global RELIEVE study).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Appropriate local ethics committee approval was obtained at all participating sites (Supplementary Table S1). Patients participated freely and provided written informed consent before study entry.

Study Outcomes

The primary study outcome was patient functioning assessed using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS).23,24 The SDS assesses functional impairment over the past week across three domains: work/school, family life/home responsibilities, and social/leisure activities. The level of impairment for each domain is rated on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (very severe); scores from the individual domains are combined to generate the SDS total score, ranging from 0 (unimpaired) to 30 (highly impaired). In patients who did not work or study during follow-up for reasons unrelated to MDD, an SDS work/school domain score was imputed for the calculation of SDS total score based on the average of the other two SDS domain scores.25

An improvement of ≥4 points in SDS total score is considered clinically relevant.24 Response was defined as SDS total score ≤12 and remission (functional recovery) as SDS score ≤6.24,25 The number of work days lost in the past week (absenteeism) and the number of underproductive work days during the past week (presenteeism) were derived from the SDS for the working population. Sick/disability leave and healthcare resource utilization were assessed during the past 12 weeks at baseline and since the last visit at weeks 12 and 24.

Secondary outcomes included depressive symptoms, cognitive function, sexual function, and quality of life. Severity of depressive symptoms was assessed by patients using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)26 and by clinicians using the Clinical Global Impressions scale.27,28 Cognitive symptoms were assessed by patients using the 5-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire-Depression (PDQ-D-5),29,30 and cognitive performance was evaluated by means of the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST).31 Sexual function was assessed using the Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale (ASEX),32 and overall health-related quality of life was assessed using the EuroQol 5-Dimensions 5-Levels questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L).33 An overview of these psychometric assessment scales is provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Any adverse events (AEs) spontaneously reported by the patient or observed by the investigator were reported according to local regulations. AEs were summarized by the lowest level Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (Version 23.1) preferred terms.

Statistical Analysis

All patients enrolled in Italy who initiated treatment with vortioxetine ≤7 days before the study baseline visit and who had a valid baseline and at least one post-baseline assessment were included in this analysis (full analysis set). Safety was assessed in all patients who initiated treatment with vortioxetine for MDD. With the exception of the SDS total score as described above, missing data were not imputed.

Changes in psychometric scale scores from baseline at weeks 12 and 24 were estimated using a linear mixed model for repeated measurements, with adjustment for clinically relevant baseline variables: age, sex, educational level, duration of current depressive episode, presence of somatic and psychiatric comorbidities, and depression severity as measured by PHQ-9 score as a continuous variable. Results are reported as estimated least-squares (LS) means, with standard errors (SEs) and P values. Change in SDS and PHQ-9 total scores from baseline at weeks 12 and 24 were also analyzed by vortioxetine treatment line (first, second, or third or later line). Changes in measures of work productivity and healthcare resource utilization from baseline at weeks 12 and 24 were analyzed by paired t test.

The proportion of patients with sexual dysfunction was calculated at baseline, week 12, and week 24. Sexual dysfunction was defined as ASEX total score ≥19, any individual ASEX item score ≥5, or a score ≥4 for any three ASEX items.32

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.1.34 Significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Study Population

This study was conducted at a total of 23 sites (22 psychiatric centers and one neurological center) in Italy between November 2017 and January 2021. Data are available for a total of 231 patients (ie, 31% of all patients included in the full analysis set for the overall RELIEVE study) (Table 1). Approximately two-thirds (62%) of patients were female. The mean patient age was 55.5 years, and over one-quarter (27%) of the patient cohort in Italy was aged >65 years. Approximately 40% of patients had a full- or part-time occupation. Over half of all patients were overweight or obese (55% of those with available body-mass index data); mean (standard deviation [SD]) body-mass index was 26.0 (4.6) kg/m2. Overall, 69% of patients reported at least one comorbid condition and 15% had three or more comorbidities. The most common comorbid medical conditions were cardiovascular diseases (22% of patients), sleep disorders (17%), diabetes (8%), and neurological disorders (7%). Almost half (47%) of all patients reported current anxiety symptoms; of these, 44% reported that they had experienced anxiety symptoms for >5 years. Type of anxiety was unspecified in 38% of patients, 7% had generalized anxiety disorder, and 6% had panic disorder.

|

Table 1 Patient Demographic Characteristics at Baseline (Full Analysis Set) |

Clinical characteristics and psychometric scale scores at baseline are shown in Table 2. The mean duration of MDD was 10.5 years, and most patients (74%) reported at least one previous MDE. The duration of the current MDE was >14 weeks in 42% of patients. Overall, the patient population had moderately severe symptoms and moderate functional impairment at baseline. Of the 93 employed patients, 27 (29%) reported taking sick or disability leave in the previous 12 weeks; this was considered by the investigator to be related to depression in 22 patients (24%). The mean (SD) number of sick/disability leave days taken in the 12 weeks before baseline was 26.6 (28.1) days (median, 15 days; range, 1–84 days). Data are available for all patients concerning healthcare resource use in the 12 weeks before baseline; patients reported a mean (SD) of 3.7 (4.8) healthcare visits during this time (median, 3 visits; range, 0–41), most commonly visits to GPs and psychiatrists.

|

Table 2 Patient Clinical Characteristics and Psychometric Assessment Scale Scores at Baseline (Full Analysis Set) |

Vortioxetine was initiated as first-line treatment for the current MDE in 53% of patients. A total of 109 patients had received prior treatment for the current MDE before the study baseline visit. Most of these patients were switching due to the lack of effectiveness of prior antidepressant therapy (75 patients [69%]). Twenty-five patients (23%) were switching due to lack of tolerability of prior therapy, three patients were switching at their own request and the remaining six patients were switching due to non-specified reasons. For the 83 patients known to have received prior antidepressants for the current MDE, the most frequently reported prior antidepressants were escitalopram (26 patients), sertraline (23 patients), paroxetine (21 patients), duloxetine (15 patients), venlafaxine (12 patients), and citalopram (12 patients).

Mean (SD) vortioxetine dosage at baseline was 9.1 (4.5) mg/day. Of the 207 patients with available dose data, just over half (n = 106 [51%]) initiated vortioxetine treatment at a dose of 10 mg/day. The starting dosage of vortioxetine was 5 mg/day in 70 patients (34%), 15 mg/day in 11 patients (5%), and 20 mg/day in 20 patients (10%).

Effectiveness

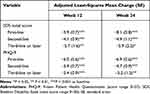

Clinically relevant improvement in overall functioning (ie, a decrease in SDS total score ≥4 points) was seen after 12 and 24 weeks of vortioxetine treatment (Figure 1A). The adjusted LS mean SDS total score decreased from 17.8 points at baseline to 12.5 points after 12 weeks of vortioxetine treatment and 11.2 points after 24 weeks. This corresponds to an adjusted LS mean (SE) change from baseline of −5.2 (0.5) points at week 12 and −6.6 (0.6) points after 24 weeks of vortioxetine treatment (both P < 0.001) (Table 3). Significant reductions in all SDS domain scores were also observed at both time points (P < 0.001 for all changes at weeks 12 and 24 vs baseline). The proportions of patients with SDS total score ≤12 (ie, SDS responders) and SDS total score ≤6 (ie, SDS remission) increased over time. SDS total score was ≤12 in 58/230 patients (25%) at baseline, 123/226 patients (54%) at week 12 and 111/182 patients (61%) at week 24. SDS total score was ≤6 in 21/230 patients (9%) at baseline, 54/226 patients (24%) at week 12 and 62/182 patients (34%) at week 24.

|

Table 3 Adjusted Least-Squares Mean Change from Baseline for Primary and Secondary Study Endpoints After 12 and 24 Weeks of Vortioxetine Treatment (Full Analysis Set) |

|

Figure 1 Adjusted LS mean (95% CI) score at baseline and after 12 and 24 weeks of vortioxetine treatment for (A) SDS total and domain scores, (B) PHQ-9, PDQ-D-5, CGI-S and ASEX, (C) DSST, and (D) EQ-5D-5L scores (full analysis set). Abbreviations: ASEX, Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (score range 5–30); CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression–Severity (score range 1–7); CI, confidence interval; DSST, Digit Symbol Substitution Test (score range 0–133); EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol 5-Dimensions 5-level utility index (score range 0–1); LS, least-squares; PDQ-D-5, 5-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire-Depression (score range 0–20); PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (score range 0–27); SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale (total score range 0–30). Notes: All changes at weeks 12 and 24, P < 0.0001 vs baseline (see Table 3). |

Significant improvement in all work productivity measures (sick leave, absenteeism, and presenteeism) was seen in the working population (ie, patients in full/part-time work or education) after 24 weeks of vortioxetine treatment (paired t test, all differences P < 0.05). At week 24, the absolute mean (SD) reduction from baseline in sick/disability leave during the preceding 12 weeks was 3.3 (11.9) days (P < 0.05). Respective mean (SD) reductions in absenteeism (work/school days lost) and presenteeism (work/school days underproductive) from baseline after 24 weeks of vortioxetine treatment were 0.6 (2.9) and 1.6 (3.1) days/week (P < 0.05 and P < 0.0001, respectively). At week 24, the mean (SD) reduction from baseline in healthcare resource utilization during the preceding 12 weeks was 1.6 (5.2) visits (paired t test, P = 0.0001).

Improvements in patient- and clinician-rated measures of depression severity, cognitive function, sexual function, and health-related quality of life were also observed after 12 and 24 weeks of vortioxetine treatment (Figure 1B–D). For all effectiveness outcomes, the adjusted LS mean changes from baseline were statistically significant at both week 12 and week 24 (all P < 0.0001) (Table 3). The proportion of patients who met the definition for sexual dysfunction decreased over the 24 weeks of vortioxetine treatment, from 84% at baseline to 76% at week 24.

Statistically significant and sustained improvements in patient functioning and depression severity were observed over the 24 weeks of treatment, irrespective of vortioxetine treatment line (Figure 2). However, numerically greater improvements in adjusted LS mean SDS and PHQ-9 total scores from baseline were seen when vortioxetine was used as first-line treatment for the current MDE compared with subsequent treatment lines. At week 24, the adjusted LS mean (SE) change in SDS total score from baseline was −8.1 (0.8) points in patients receiving vortioxetine as first-line treatment (P < 0.0001), −4.9 (1.1) points in those receiving vortioxetine as second-line treatment (P < 0.0001), and −5.9 (2.2) points in those for whom vortioxetine was third- or later-line treatment (P = 0.0128) (Table 4). Corresponding adjusted LS mean (SE) changes in PHQ-9 total score from baseline were −6.9 (0.6) points (P < 0.0001), −4.7 (0.9) points (P < 0.0001), and −5.2 (1.5) points (P = 0.0024), respectively.

|

Table 4 Adjusted Least-Squares Mean Change from Baseline for SDS and PHQ-9 Total Score After 12 and 24 Weeks of Vortioxetine Treatment According to Treatment-Line (Full Analysis Set) |

|

Figure 2 Adjusted LS mean (95% CI) score at baseline and at 12 and 24 weeks according to vortioxetine treatment for (A) SDS total score and (B) PHQ-9 score (full analysis set). Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LS, least-squares; PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (score range 0–27); SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale (total score range 0–30). Notes: All changes at weeks 12 and 24, P < 0.0001 vs baseline for first- and second-line treatment and P < 0.05 for third-line treatment or later (see Table 4). |

Safety

At least one AE was reported over the 24 weeks of vortioxetine treatment in 29 patients (13%). The most commonly reported AE was nausea (14 patients, 6%). No other AEs were reported by >5% of patients. Only 11 patients discontinued treatment with vortioxetine due to AEs (5 patients by the week 12 visit and a further 6 patients by the week 24 visit).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the effectiveness of vortioxetine for the treatment of MDD in routine practice settings in Italy. In line with the global RELIEVE study findings,21 clinically meaningful and sustained improvements in overall functioning, depressive symptoms, cognitive function, and quality of life were observed in patients with MDD treated with vortioxetine in routine practice settings over a period of 6 months. Significant improvements in all outcome assessments were seen after 3 months of vortioxetine treatment, with further improvements observed after 6 months. This finding confirms the importance of continuing antidepressant treatment for at least 6 months in patients with MDD to achieve maximum therapeutic effects, as recommended in current treatment guidelines.35

Improvement in measures of sexual functioning was observed over the 6 months of vortioxetine treatment, including a reduction in both mean ASEX total score and the proportion of patients who met the definition for sexual dysfunction. This is encouraging, as sexual side effects are one of the main reasons for poor adherence and treatment discontinuation in patients receiving selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.36,37 Indeed, treatment with vortioxetine was found to be well tolerated in this study. No unexpected AEs were reported and very few patients discontinued treatment due to AEs. While greater adherence to treatment may be expected in a clinical trial setting due to more frequent patient follow-up, it should be noted that in this study patients were receiving treatment in routine practice settings and were only seen at 3-month intervals.

Our findings are particularly noteworthy as the cohort in Italy included a relatively high proportion of elderly patients and patients with medical comorbidities, and almost half of all patients reported current anxiety symptoms. Physicians may have been more likely to prescribe vortioxetine than other antidepressants in these patients due to its established efficacy and tolerability profile.13,38 In particular, the well-documented lack of weight gain during treatment with vortioxetine may have influenced its use in overweight/obese patients; many other drugs for depression are associated with the potential for weight gain.39

These results are consistent with those of other studies in patients with MDD treated with vortioxetine in routine care settings.40–44 The observed improvement in functioning, as assessed by change in mean SDS total score from baseline at weeks 12 and 24 (approximately 5 and 7 points, respectively), was greater than the threshold considered meaningful for patients (ie, ≥4 points).24 Improvements of similar magnitude were observed across all SDS domains (work/school, social life/leisure, and family/home life). Working patients also reported missing significantly fewer days of work and were more productive while at work during treatment with vortioxetine. A reduction in healthcare resource utilization was also observed over the 6 months of vortioxetine treatment.

The observed improvements in DSST and PDQ-D-5 scores show vortioxetine to be effective for the treatment of objective and subjective cognitive symptoms in patients with MDD, in keeping with the results of earlier randomized controlled trials,15,45–49 and observational studies.40–44 DSST scores were lower in the cohort in Italy than in the global RELIEVE study population, both at baseline and at 24 weeks.21 This may at least in part be due to the high proportion of elderly patients in the Italian cohort; performance on cognitive tests that require rapid processing of information, such as the DSST, tends to decline with age.50 Obesity has also been shown to be associated with cognitive impairment,51–53 and over half of all patients in this patient cohort were considered overweight or obese. Nevertheless, the LS mean change in DSST score from baseline to week 24 in the patient cohort in Italy was similar to that seen in the overall study population (5.2 vs 6.2 points, respectively).21

Almost half of all patients in this cohort also had symptoms of anxiety at study baseline. Anxiety symptoms are common in patients with MDD,54–56 and have been shown to be associated with lower rates of treatment response and remission, increased risk of recurrence, and greater functional impairment.55–58 Other studies have shown treatment with vortioxetine to be effective in patients with MDD and high levels of concurrent anxiety symptoms,14,41 and in patients with comorbid anxiety disorders.59–61 Although the impact of vortioxetine on anxiety was not assessed in the present study, it is possible that a beneficial effect of treatment on anxiety symptoms may have contributed to the improvement seen in functioning and quality of life.

Of note, just over half of all patients were receiving vortioxetine as a first-line antidepressant treatment in real-world clinical practice settings in Italy. As in the global RELIEVE study,21 the greatest improvements in patient functioning and depressive symptom severity were observed when vortioxetine was used as first-line therapy. However, clinically meaningful improvements were also seen in patients who had received prior antidepressant therapy for the current MDE.

The main strength of this study is that it was conducted in a heterogeneous patient population representative of the patients likely to be encountered in daily clinical practice in Italy, many of whom have clinically relevant comorbidities. In particular, the proportion of elderly patients in the patient cohort was similar to that in the general population in Italy. In 2020, individuals aged ≥65 years accounted for 23% of the total population in Italy and this proportion is projected to increase further in coming years.62 A further study strength is the use of patient-reported outcome measures to assess functional impairment and MDD symptoms. This is in keeping with the increased awareness of the importance of addressing patient perspectives when managing mental health disorders such as MDD.63 Clinician-rated assessments may not fully capture a patient’s subjective experience of MDD and antidepressant treatment, and patients’ perceptions of symptoms and treatment outcomes in MDD have been shown to differ from those of their physicians.64–66 Potential limitations include the open-label study design and lack of a placebo or active comparator, and the fact that the patient cohort in Italy almost exclusively comprised White/Caucasian patients (98% of all patients). Due to the relatively infrequent study visits (ie, at baseline and after 3 and 6 months of treatment), collection of vortioxetine dose data was limited, precluding assessment of vortioxetine dosage across the study period.

Conclusions

In summary, the results of this study demonstrate the real-world effectiveness and good safety profile of vortioxetine in patients with MDD treated in routine practice settings in Italy. Clinically relevant and sustained improvements in overall functioning, work productivity, symptoms of depression, cognitive symptoms, and health-related quality of life were observed in the heterogeneous and representative population of patients with MDD over the 6 months of vortioxetine treatment, including a high proportion of elderly patients.

Data Sharing Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript. The corresponding author may be contacted for further data sharing.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the following principal investigators at the participating Italian study sites: Eugenio Aguglia, Silvio Bellino, Antonello Bellomo, Giuseppe Bersani, Massimo Biondi, Roberto Brugnoli (co-investigator), Domenico Buccomino, Gaetano Callista, Massimo Clerici, Bernardo Dell’Osso, Giovanni Dominici, Pasquale De Fazio, Sergio De Filippis, Serafino De Giorgi, Marco Di Nicola, Orsola Gambini, Giuseppe Maina, Giuseppe Nicolò, Stefano Pallanti, Giampaolo Perna, Maurizio Pompili, Gianluca Rosso, Gabriele Sani, Fabrizio Stocchi, Alfonso Tortorella, Caterina Viganò, and Antonio Vita. Medical writing assistance was provided by Jennifer Coward of Piper Medical Communications, funded by H. Lundbeck A/S.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The RELIEVE study was funded by H. Lundbeck A/S, whose personnel contributed to the data analysis, review of the data, and review of this manuscript.

Disclosure

SDF has been a consultant and/or speaker for the following organizations: Angelini Pharma, ArcaPharma, DI.RA.LAB, Ecupharma, Janssen, Lundbeck, Mylan, Molteni, Neuraxpharma, and Otsuka. AP is an employee of Lundbeck Italy S.p.A. MCC is an employee of H. Lundbeck A/S. GR reports grants from Lundbeck during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Janssen Cilag; and personal fees from Lundbeck, Angelini Pharma, Otsuka, Viatris, and GlaxoSmithKline, outside the submitted work. MDN has been a speaker for Angelini, Janssen, Lundbeck, Neuraxpharma, and Otsuka. KS and HR were employees of H. Lundbeck A/S at the time this study was conducted.

References

1. GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–1858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

2. World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Available from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf.

3. Italian National Institute of Statistics (Istat). Mental health at various stages of life: years 2015–2017. Available from: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2018/07/Mental-health.pdf.

4. Fiorillo A, Sampogna G, Giallonardo V, et al. Effects of the lockdown on the mental health of the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: results from the COMET collaborative network. Eur Psychiatry. 2020;63(1):e87. doi:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.89

5. Amerio A, Lugo A, Stival C, et al. COVID-19 lockdown impact on mental health in a large representative sample of Italian adults. J Affect Disord. 2021;292:398–404. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.117

6. Medda E, Toccaceli V, Gigantesco A, Picardi A, Fagnani C, Stazi MA. The COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: depressive symptoms immediately before and after the first lockdown. J Affect Disord. 2021;298(PtA):202–208. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.129

7. Lam RW, Parikh SV, Michalak EE, Dewa CS, Kennedy SH. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) consensus recommendations for functional outcomes in major depressive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2015;27(2):142–149.

8. IsHak WW, James DM, Mirocha J, et al. Patient-reported functioning in major depressive disorder. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2016;7(3):160–169. doi:10.1177/2040622316639769

9. Lam RW, McIntosh D, Wang J, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: Section 1. Disease burden and principles of care. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):510–523. doi:10.1177/0706743716659416

10. Gonda X, Sharma SR, Tarazi FI. Vortioxetine: a novel antidepressant for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2019;14(1):81–89. doi:10.1080/17460441.2019.1546691

11. European Medicines Agency. Brintellix. Vortioxetine. Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/002717. Applicant: H. Lundbeck A/S. Assessment Report for an Initial Marketing Authorisation Application. Europe: European Medicines Agency; 2013.

12. Sanchez C, Asin KE, Artigas F. Vortioxetine, a novel antidepressant with multimodal activity: review of preclinical and clinical data. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;145:43–57. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.07.001

13. Thase ME, Mahableshwarkar AR, Dragheim M, Loft H, Vieta E. A meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials of vortioxetine for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(6):979–993. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.03.007

14. Baldwin DS, Florea I, Jacobsen PL, Zhong W, Nomikos GG. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of vortioxetine in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and high levels of anxiety symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2016;206:140–150. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.015

15. McIntyre RS, Harrison J, Loft H, Jacobson W, Olsen CK. The effects of vortioxetine on cognitive function in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of three randomized controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19(10):pyw055. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyw055

16. Florea I, Loft H, Danchenko N, et al. The effect of vortioxetine on overall patient functioning in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. 2017;7(3):e00622. doi:10.1002/brb3.622

17. Christensen MC, Florea I, Lindsten A, Baldwin DS. Efficacy of vortioxetine on the physical symptoms of major depressive disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(10):1086–1097. doi:10.1177/0269881118788826

18. Christensen MC, McIntyre RS, Florea I, Loft H, Fagiolini A. Vortioxetine 20 mg/day in patients with major depressive disorder: updated analysis of efficacy, safety, and optimal timing of dose adjustment. CNS Spectr. 2021;18:1–26. doi:10.1017/S1092852921000936

19. Iovieno N, Papakostas GI, Feeney A, et al. Vortioxetine versus placebo for major depressive disorder: a comprehensive analysis of the clinical trial dataset. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(4):20r13682. doi:10.4088/JCP.20r13682

20. McIntyre RS, Loft H, Christensen MC. Efficacy of vortioxetine on anhedonia: results from a pooled analysis of short-term studies in patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:575–585. doi:10.2147/NDT.S296451

21. Mattingly GW, Ren H, Christensen MC, et al. Effectiveness of vortioxetine in patients with major depressive disorder in real-world clinical practice: results of the RELIEVE study. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:824831. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.824831

22. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

23. Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(Suppl 3):89–95. doi:10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015

24. Sheehan KH, Sheehan DV. Assessing treatment effects in clinical trials with the discan metric of the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(2):70–83. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f2b4d6

25. Sheehan DV, Harnett‐Sheehan K, Spann ME, Thompson HF, Prakash A. Assessing remission in major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder clinical trials with the discan metric of the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(2):75–83. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e328341bb5f

26. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, The PHQ-9. validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

27. Guy W, editor. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration); 1976.

28. Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry. 2007;4(7):28–37.

29. Lam RW, Lamy FX, Danchenko N, et al. Psychometric validation of the Perceived Deficits Questionnaire-Depression (PDQ-D) instrument in US and UK respondents with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:2861–2877. doi:10.2147/NDT.S175188

30. Fehnel SE, Forsyth BH, Dibenedetti DB, Danchenko N, François C, Brevig T. Patient-centered assessment of cognitive symptoms of depression. CNS Spectr. 2016;21(1):43–52. doi:10.1017/S1092852913000643

31. Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1981.

32. McGahuey CA, Gelenberg AJ, Laukes CA, et al. The Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX): reliability and validity. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(1):25–40. doi:10.1080/009262300278623

33. EuroQol Research Foundation. EQ-5D-5L User Guide. Version 3.0. EuroQol Research Foundation, Rotterdam; 2019. Available from https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides.

34. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016. Available from http://www.R-project.org/.

35. Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, et al.; CANMAT Depression Work Group. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: Section 3. Pharmacological Treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):540–560. doi:10.1177/0706743716659417

36. Baldwin DS, Manson C, Nowak M. Impact of antidepressant drugs on sexual function and satisfaction. CNS Drugs. 2015;29(11):905–913. doi:10.1007/s40263-015-0294-3

37. Atmaca M. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction: current management perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:1043–1050. doi:10.2147/NDT.S185757

38. Baldwin DS, Chrones L, Florea I, et al. The safety and tolerability of vortioxetine: analysis of data from randomized placebo-controlled trials and open-label extension studies. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(3):242–252. doi:10.1177/0269881116628440

39. Uguz F, Sahingoz M, Gungor B, Aksoy F, Askin R. Weight gain and associated factors in patients using newer antidepressant drugs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(1):46–48. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.10.011

40. Chin CN, Zain A, Hemrungrojn S, et al. Results of a real-world study on vortioxetine in patients with major depressive disorder in South East Asia (REVIDA). Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(11):1975–1984. doi:10.1080/03007995.2018.1477746

41. Chokka P, Bougie J, Proulx J, Tvistholm AH, Ettrup A. Long-term functioning outcomes are predicted by cognitive symptoms in working patients with major depressive disorder treated with vortioxetine: results from the AtWoRC study. CNS Spectr. 2019;24(6):616–627. doi:10.1017/S1092852919000786

42. Fagiolini A, Florea I, Loft H, Christensen MC. Effectiveness of vortioxetine on emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder with inadequate response to SSRI/SNRI treatment. J Affect Disord. 2021;283:472–479. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.106

43. Yang YK, Chen CS, Tsai CF, et al. A Taiwanese study on real-world evidence with vortioxetine in patients with major depression in Asia (TREVIDA). Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(12):2163–2173. doi:10.1080/03007995.2021.1980869

44. Papalexi E, Galanopoulos A, Kontis D, et al. Real-world effectiveness of vortioxetine in outpatients with major depressive disorder: functioning and dose effects. BMC Psychiatry. In Press 2022.

45. Baune BT, Sluth LB, Olsen CK. The effects of vortioxetine on cognitive performance in working patients with major depressive disorder: a short-term, randomized, double-blind, exploratory study. J Affect Disord. 2018;229:421–428. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.056

46. McIntyre RS, Lophaven S, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of vortioxetine on cognitive function in depressed adults. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(10):1557–1567. doi:10.1017/S1461145714000546

47. Mahableshwarkar AR, Zajecka J, Jacobson W, Chen Y, Keefe RS. A randomized, placebo-controlled, active-reference, double-blind, flexible-dose study of the efficacy of vortioxetine on cognitive function in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:2025–2037. doi:10.1038/npp.2015.52

48. McIntyre RS, Florea I, Tonnoir B, Loft H, Lam RW, Christensen MC. Efficacy of vortioxetine on cognitive functioning in working patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(1):115–121. doi:10.4088/JCP.16m10744

49. Vieta E, Sluth LB, Olsen CK. The effects of vortioxetine on cognitive dysfunction in patients with inadequate response to current antidepressants in major depressive disorder: a short-term, randomized, double-blind, exploratory study versus escitalopram. J Affect Disord. 2018;227:803–809. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.053

50. Murman DL. The impact of age on cognition. Semin Hear. 2015;36(3):111–121. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1555115

51. Cournot M, Marquié JC, Ansiau D, et al. Relation between body mass index and cognitive function in healthy middle-aged men and women. Neurology. 2006;67(7):1208–1214. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000238082.13860.50

52. Dye L, Boyle NB, Champ C, Lawton C. The relationship between obesity and cognitive health and decline. Proc Nutr Soc. 2017;76(4):443–454. doi:10.1017/S0029665117002014

53. Zhou Y, Zhang T, Lee D, Yang L, Li S. Body mass index across adult life and cognitive function in the American elderly. Aging. 2020;12(10):9344–9353. doi:10.18632/aging.103209

54. Kessler RC, Sampson NA, Berglund P, et al. Anxious and non-anxious major depressive disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2015;24(3):210–226. doi:10.1017/S2045796015000189

55. Dold M, Bartova L, Souery D, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid anxiety disorders – results from a European multicenter study. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;91:1–13. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.02.020

56. Gaspersz R, Nawijn L, Lamers F, Penninx BWJH. Patients with anxious depression: overview of prevalence, pathophysiology and impact on course and treatment outcome. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31(1):17–25. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000376

57. Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, et al. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):342–351. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111868

58. Saveanu R, Etkin A, Duchemin AM, et al. The international Study to Predict Optimized Treatment in Depression (iSPOT-D): outcomes from the acute phase of antidepressant treatment. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;61:1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.12.018

59. Bidzan L, Mahableshwarkar AR, Jacobsen P, Yan M, Sheehan DV. Vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) in generalized anxiety disorder: results of an 8-week, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(12):847–857. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.07.012

60. Liebowitz MR, Careri J, Blatt K, et al. Vortioxetine versus placebo in major depressive disorder comorbid with social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(12):1164–1172. doi:10.1002/da.22702

61. Christensen MC, Schmidt S, Grande I. Effectiveness of vortioxetine in patients with major depressive disorder comorbid with generalized anxiety disorder: results of the open-label RECONNECT study. J Psychopharmacol. 2022;36(5):566–577. doi:10.1177/02698811221090627

62. Italian National Institute of Statistics (Istat). Households and population projections: 1/1/2020. Available from: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2021/11/Households-and-population-projections.pdf.

63. IsHak WW, Mirocha J, Pi S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes before and after treatment of major depressive disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2014;16(2):171–183. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.2/rcohen

64. Demyttenaere K, Donneau AF, Albert A, Ansseau M, Constant E, van Heeringen K. What is important in being cured from depression? Discordance between physicians and patients. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:390–396. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.004

65. Baune BT, Christensen MC. Differences in perceptions of major depressive disorder symptoms and treatment priorities between patients and health care providers across the acute, post-acute, and remission phases of depression. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:335. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00335

66. Christensen MC, Wong CMJ, Baune BT. Symptoms of major depressive disorder and their impact on psychosocial functioning in the different phases of the disease: do the perspectives of patients and healthcare providers differ? Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:280. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00280

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.