Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Effect of Organizational Socialization of New Employees on Team Innovation Performance: A Cross-Level Model

Authors Liao G , Zhou J, Yin J

Received 29 January 2022

Accepted for publication 10 April 2022

Published 21 April 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 1017—1031

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S359773

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Ganli Liao, Jiao Zhou, Jielin Yin

School of Economics and Management, Beijing Information Science and Technology University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Ganli Liao, School of Economics and Management, Beijing Information Science and Technology University, No. 12, Xiaoying East Road, Haidian District, Beijing, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 18810295416, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Based on the Social Information Processing Theory, a cross-level model was conducted to analyze the influence of new employees’ organizational socialization on team innovation performance via the mediating effect of employee voice behavior and the moderating effect of servant leadership.

Methods: Survey data were collected from 352 new employees and 88 leaders at two stages in major Chinese innovation companies. Samples were involved technology and development, production and operation, marketing and sales, and functional management departments. The software Mplus 7.0 and AMOS 22.0 were used to test the hypotheses.

Results: The cross-level results indicated that organizational socialization directly enhances new employee voice behavior and, accordingly, promotes team innovation performance. Additionally, servant leadership plays a moderating role between organizational socialization and prohibitive voice behavior but has no moderating effect on the relationship between organizational socialization and promotive voice behavior.

Conclusion: The results enrich the research on the influencing mechanism of organizational socialization on team innovation performance and provide a theoretical basis and practical guidance for innovation enterprise leaders on how to promote team innovation performance.

Keywords: new employees, organizational socialization, employee voice behavior, servant leadership, team innovation performance, cross-level model

Introduction

With rising labor mobility, the psychology, attitudes, and behaviors of new employees, as important human capital, have drawn much attention in organizational development.1 Undoubtedly, new employees, including both fresh graduates and those who experience career changes, might face problems such as uncertainty in the organizational environment, team adaptability, or expectation deviations.2 At this stage, organizational socialization tactics such as organizational norm learning, organizational culture exposure, or job skill training are essential for new employees to adapt to new jobs, and learn to take on new roles in the organization.3,4 Organizational socialization is a vital process for facilitating individuals to enhance their understandings of organizational goals, behavioral norms, and responsibilities as well as to become insiders of the organization through providing new employees with learning opportunities.5 It has attracted extensive attention from scholars as a key source of the competitive advantages of organization.6

Current studies related to organizational socialization focus more on the levels of individual and organization-individual interaction.7 At the individual level, studies show that organizational socialization has positive effects on individuals’ attitudes, cognition and behaviors.8–10 When individuals perceive various strategies implemented by the organization, they can generate greater organizational identification,11 thus improving their job involvement and satisfaction.12,13 These will further promote positive behaviors of employees, such as organizational citizenship behavior, knowledge sharing behavior, and information search behavior.14,15 Moreover, scholars have also found that organizational socialization has a significant negative relationship with individual turnover intention,16 which motivates employees’ work initiative17 and contributes to the improvement of individual and organizational performance.18–20 Regarding the level of organization-individual interaction, Kim et al and Xu et al proposed that organizational socialization could enhance the person-organization fit of new employees.21,22 Yang et al revealed that employees who constantly adapt to organizational roles, the environment and culture in the socialization process would significantly enhance the trust between organizational members, increasing an individual’s knowledge sharing behavior and innovation performance.23 Evidently, most scholars focus on the influence of new employees’ socialization on individual or organizational innovations.24 However, the impact of socialization tactics on team behavior has rarely been studied. With the advent of a new round of technological and industrial revolution, enterprises have engaged in innovative activities with the team as a basic organizational form.25 As a result, the study of team innovation has become a major focus in the industrial and academic fields. Scholars such as Deng (2019) have studied the mechanism of various antecedent variables and team innovation from the perspectives of the external environment, team culture, and leadership style in accordance with the Social Exchange Theory.26–28 In that case, will team innovation performance be improved by strengthening new employees’ innovative behaviors in the organizational socialization process?

To answer this question, this study investigated the relationship between organizational socialization and team innovation performance based on the Social Information Processing Theory first proposed by Maanen and Schein.29 They posited that the work attitudes and motivations of an employee are the results of the influence of the social environment and previous choices rather than a process of rational decision-making.30 Individuals adjust their work attitudes and behaviors based on self-perception and motivation formed by information that is acquired from the work environment. New employees can identify attitudes and behaviors that are accepted by the organization through various continuously processing tactics.31 Moreover, after interpreting and analyzing the socialization tactics, new employees will focus on specific tactics and amplify the significance of this socialized information to their current state and future career development. Hence, they will pay more attention to those behaviors corresponding to the specific socialized information. Previous studies have shown that organizational socialization tactics can help new employees attain more organizational resources, such as normative organizational learning, organizational culture adaptation, and job skill training.6 New employees can assimilate into the organization quickly by processing those organizational resources, acquiring a sense of recognition and establishing extensive social connections with team members. All of these contribute to creating an environment for team innovation.32 In addition, the influence of organizational socialization on employee voice behavior is exactly the prerequisite and guarantee for employee innovation, which also has a direct impact on team innovation performance. Therefore, this study argues that new employees who interpret and process organizational socialization tactics and establish a strong social network with the team can enhance their voice behavior, thus improve team innovation performance. In addition, the Social Information Processing Theory is also one of the important theoretical bases of leadership behavior research.28 Leadership is a process in which the leader aims to influence subordinates through a series of personalized behaviors using the leadership activity process as a carrier, the pursuit of leadership effectiveness as an objective, and leadership behavior as the main form.33,34 Therefore, as the principal receiver of voice behavior, servant leadership can directly affect the employee’s assessment of risks and profits of voice behavior.35

In sum, this study attempts to make three major contributions. First, this study examines the relationship between organizational socialization tactics and team innovation performance based on Social Information Processing Theory, which enriches the research on organizational socialization and team innovation performance. Second, this study estimates the cross-level mediating effect between organizational socialization and team innovation performance, which helps people better understand the relationship between these factors. Third, the study uses servant leadership as the moderating variable between organizational socialization and employee voice behavior, which expands the application scope of servant leadership in innovative enterprises. Therefore, this study provides further guidance on new employees’ organizational socialization and team innovation performance.

Theory and Hypotheses

Organizational Socialization and Team Innovation Performance

Organizational socialization, which was proposed by Maanen and Schein, mainly refers to the process of new employees becoming insiders from outsiders of the organization.29 It is a process in which individuals acquire attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge before becoming members of an organization, and a process of developing roles and their social identities. Studies have confirmed the leading role of organizational socialization, suggesting that it is conducive to promoting new employees to continuously become familiar with organizational culture, recognize organizational values, adapt to organizational goals, and comply with the behavioral norms of the organization.36,37 According to Jones, organizational socialization is a range of management systems that facilitate new employees’ integration into the organization, which is divided into situational tactics, content tactics, and social tactics.38 They are associated with the background of strategy implementation, the information provided, and the content of interpersonal communication in the socialization process. Moreover, organizational socialization emphasizes the interaction between new employees and the organization. In other words, new employees shall proactively integrate themselves into the organization by learning the enterprise system and adapting to the team role.39

Innovation performance is the main indicator for evaluating the implementation effect of organizational socialization, which has drawn wide attention from scholars in the contextual study of socialization, and a consistent conclusion has been reached.40 This study proposes that team innovation performance can be effectively enhanced by organizational socialization. In fact, team innovation performance is not a simple summary of team members’ innovation performance, but is gradually manifested by team members in the process of interaction between the environment, individual and society. According to the Social Information Processing Theory, individuals will input, encode and store organizational information. Then, they adjust their behaviors according to the organizational context, and continuously interact in a specific external environment and cultural background before taking corresponding actions.41,42 While receiving socialization strategies and positive interaction, new employees can establish benign interpersonal interactions with team members and gradually become team members by weakening interpersonal communication barriers.30 This means that the higher the organizational socialization of new employees, the greater the employees’ awareness of the identity of a team member. Other individuals on the team are observers of employee behavior performance. When others are present, they aim to arouse employees’ competitive instincts.43 In addition, new employees expect to acquire positive feedback from team members.44 Therefore, they will enhance internal motivation, stimulate their innovative abilities, and contribute to improving team innovation performance. According to previous research findings, when new employees join a team, those with high organizational socialization will develop strong social network relationships and provide favorable conditions for fusing innovative ideas and knowledge between members.45 This kind of interactive communication allows team members to address problems using extensive perspectives, skills, and information, and to propose better solutions for enhancing team innovation performance.46,47 Besides, situational tactics and content tactics are suitable for new employees to adapt to the dynamic organizational environment, which can help them recognize the organizational values. At the same time, new employees will have a higher level of identification with the organization.39 The matching and identification of employees with organizational values are significant factors affecting individuals’ innovation behaviors.7,48 Since the team is a symbol of the organization’s identity, new employees’ belonging and identification of the organization are associated with the belonging and identification of the team. New employees’ innovative behaviors will ultimately improve team innovation performance. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1. Organizational socialization of new employees is positively related to team innovation performance.

Mediating Effect of Employee Voice Behavior

Voice behavior is an employee’s conduct of promoting organizational innovation and adapting to a dynamic organizational environment by expressing constructive opinions, concerns or ideas.49 Liang et al divided voice behavior into promotive voice behavior and prohibitive voice behavior according to the voice content.50 Promotive voice behavior refers to the behavior of proposing innovative ideas and solutions for teams or organizations. Prohibitive voice behavior refers to employees’ concerns about potential disadvantages of the organization. Although voice behavior is obviously beneficial to the development of organization, it is a deliberate process for employees who consider both positive and negative consequences.51 Employees’ choice of withholding or sharing ideas is affected by various factors, such as concerns about negative performance evaluation or their own reputation. Thus, employees need to evaluate whether the organizational environment contributes to improving the effectiveness of voice behaviors before making behavioral decisions. This means that the organizational environment has a significant impact on the frequency of employees’ voice behaviors.52

Organizational socialization, consisting of organizational culture, organizational climate, and work team norms, is an interactive process between new employees and the organization. It has a significant impact on new employees’ voice behavior because it is a stage for them to adjust and adapt to the new workplace and form a preliminary understanding of the organization.53 Based on Social Information Processing Theory, new employees will gradually identify and internalize organizational norms and culture after processing various organizational socialization tactics and accomplishing role transitions from outsiders to insiders. Employees with a high level of organizational socialization tend to keep their personal interests in line with organizational interests.54 When organizational interests are damaged, those who identify with the organization are inclined to protect organizational interests. When the organization encounters problems, those who identify with the organization are more willing to offer constructive ideas.55 Organizational socialization contributes to raising the organizational identity perceived by new employees and lowering their risk assessments of voice behavior.56 This can also increase the possibility of new employees solving problems, thereby promoting their voice behaviors. Meanwhile, effective organizational socialization can also enable new employees to readjust their expectations to balance themselves with reality and promote job satisfaction. Those who are more satisfied with the organization or team are more interested in offering constructive suggestions to promote organizational development.57,58 Moreover, activities related to the enhancement of employees’ innovation ability in the process of organizational socialization can help employees to improve their innovation capability and increase their innovation willingness, which plays a positive role in promotive voice behavior.59 Thus, we propose that,

H2. Organizational socialization of new employees is related to employee voice behavior. H2a. Organizational socialization of new employees is positively related to promotive voice behavior. H2b. Organizational socialization of new employees is positively related to prohibitive voice behavior.

In today’s complicated and volatile work environments, team innovation requires more contributions not only from team leaders but also from employees involved in daily operations. Voice behavior is one of the critical paths for employees to promote team innovation.60 According to the different definitions of promotive and prohibitive voice behavior, this study investigates how these two different voice behaviors affect team innovation performance.

Promotive voice behavior focuses on the ideal state of the team in the future by proposing innovative solutions and suggestions, which can positively affect team learning and creativity and improve team innovation performance.61–63 This influence mechanism includes three aspects. First, promotive voice behavior, in general, puts forward innovative approaches for perfecting the work process and enhancing the team climate. This not only improves teamwork efficiency but also promotes the creation of an innovative atmosphere and increases the possibility of team innovative behavior.64 Next, the knowledge, perspectives and experiences shared by employees, as well as new ideas generated in the process of their work, expose other team members to a diverse information environment. This will promote the possibility of team learning and cross-border behavior, which will have a positive impact on team innovation performance.65,66 Third, leaders will give more support to employees who develop innovative and forward-looking ideas. By doing so, positive interaction can be formed between employees and leaders, not only enhancing employee self-efficacy and team trust but also promoting employee innovation and resource sharing, and ultimately, increasing team innovation performance.67,68

The relationship between prohibitive voice behavior and team innovation performance includes the following four aspects. First, various new problems will emerge from the traditional context in the innovation process.69 In this case, prohibitive voice behavior is a good way for the team to identify harmful internal factors, promote the solution of problems and reduce the risk of failure, to enhance team innovation performance.70,71 Second, the key to prohibitive voice behavior lies in uncovering negative situations. Namely, prohibitive voice behavior is a channel available for employees to release their complaints, facilitating employees in maintaining a positive working state.72 Such a state is more beneficial to producing innovative ideas and behaviors, and better elevating team innovation performance. Third, Liang et al believe that employees propose the prohibitive voice behavior is based on psychological factors such as safety and discretion. Employees tend to adopt prudent strategies in their work and consciously avoid factors that may cause losses and failures.50 Moreover, employee performance and team performance can be improved since adopting a prudent strategy can increase work accuracy and lower the possibility of making mistakes. Finally, team leaders can make a correct decision in the face of possible problems in team innovation based on the information they obtained from the employees. Even in some cases, prohibitive voice behavior is more effective than promotive voice behavior, since the prohibitive voice can easily point out problems in the organization. Obviously, prohibitive voice behavior is more “cost-effective” from the cost-benefit perspective. Thus, we propose that,

H3. Employee voice behavior mediates the relationship between organizational socialization and team innovation performance. H3a. Promotive voice behavior mediates the relationship between organizational socialization and team innovation performance. H3b. Prohibitive voice behavior mediates the relationship between organizational socialization and team innovation performance.

Moderating Effect of Servant Leadership

Servant leadership is a leadership style that priorities subordinates’ future development and personal needs and that always puts the interests of the organization and employees first.73 Those leaders communicate and interact with employees in a timely manner, trust and respect employees, and focus on individual initiative; they also engage in teamwork in an attempt to achieve organizational goals in a friendly and harmonious working environment. Servant leadership provides organizational supports to subordinates by means of serving others, positive dedication and reasonable authorization, so that they can positively interact with employees. Furthermore, they have a positive impact on employee performance by motivating employees to engage in positive behaviors such as innovative behaviors, voice behaviors, and organizational citizenship behavior.

Referring to the Social Information Processing Theory, Lu et al found that servant leadership influences the superficial and deep behaviors of subordinates.74 Leaders in the workplace are role models imbued with complex information and social cues, who are crucial for guiding employees to perceive the environment according to their ways of doing things and leadership styles.75 Servant leadership is typically characterized by modesty, sincerity, interpersonal acceptance, and authorization.73 Leaders with these characteristics can easily generate high-quality relationships with employees, create a relaxed and pleasing working atmosphere in the organization, and convey an inclusive leadership model to employees. In addition, individuals are provided with greater autonomy and tend to work hard to identify and address problems as well as contribute ideas to the team.76 Meanwhile, servant leaders who are approachable and open-minded are more likely to create an environment filled with trust as well as a variety of formal and informal voice environments. In this way, employees are immersed in a secured work environment under the synergy of organizational socialization, allowing them to hold a positive attitude towards the efficiency and safety of voice behavior.77 Furthermore, servant leadership can provide effective listening with considerations in new employees of various backgrounds, strengths, and interests, which can lead to a harmonious interpersonal atmosphere, thereby effectively improving employee satisfaction with the team. Those with high satisfaction are more willing and more likely to propose constructive suggestions for team development.78 The study found that new employees will be willing to take risks, and to be sensitive to the positive characteristics of the environment under a high level of servant leadership with an active and open attitude. Employees will initiatively respond to leadership with a sincere attitude and achieve their ideal goals and conditions by adopting proactive strategies and increasing voice behavior in a harmonious and friendly working atmosphere. Thus, we propose that,

H4. Servant leadership moderates the relationship between organizational socialization and employee voice behavior. H4a. Servant leadership moderates the relationship between organizational socialization and promotive voice behavior. H4b. Servant leadership moderates the relationship between organizational socialization and prohibitive voice behavior.

The theoretical model is shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Theoretical model. |

Methods

Data Collection and Sample Description

The samples were collected from 8 innovation enterprises in China, involved in new energy, new materials, information technology and other innovation enterprises. Before conducting the survey, we obtained formal approval from the Ethics Committee for Research at the School of Economics and Management, Beijing Information Science and Technology University. In this study, no vulnerable populations were involved. In addition, our researchers and the HR directors of the enterprise introduced the survey and informed the participants of the study’s aim, duration, and how to obtain information on the results. Those who agreed to participate in this study signed an informed consent form. Responses were kept completely confidential, to the extent permitted by law. This study was performed in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Through the above series of statements, 94 innovation teams and new employees with an average tenure of fewer than 6 months were invited to participate in the data collection process. To avoid Common Methods Bias, the sample data were collected from new employees and their leaders in two periods.79 At Time T1, 442 questionnaires were sent to new employees to measure their demographic information and the perception of organizational socialization. Then, 413 questionnaires (93.4%) consisting of 94 teams were returned. Three months later (Time T2), the 413 new employees reported their voice behavior, and 94 team leaders reported their servant leadership and team innovation performance. A total of 378 employee questionnaires and 91 leader questionnaires were collected. After invalid questionnaires with a deletion rate over 10% and a repetition rate over 90% were eliminated, 352 questionnaires (consisting of 88 teams) were returned, with recovery rates of 85.2% and 93.6%, respectively.

Among the 88 team samples, in terms of team leaders, 73.6% were male and 26.4% were female. In addition, 24.2% had college degrees, 54.9% had bachelor’s degrees and 20.9% had master’s degrees or above. In terms of new employees, 60.2% were male, 39.8% were female, 17.3% had junior college degrees, 47.7% had bachelor’s degrees, and 35.0% had master’s degree or above.

Measures

All variables in this study were measured from mature scales published in top journals. To ensure the reliability and validity of the scale, the back-translation method was adopted by researchers and Ph. D. students. All variables were measured using a Likert 5-point scale.

Organizational Socialization

At time T1, we assessed organizational socialization using Jones’ scale (1983) with three dimensions.38 The scale includes situational tactics (4 items), content tactics (4 items) and social tactics (4 items), which are reported by new employees. Sample items of situational tactics items such as “Some experienced colleagues will try their best to help me adapt to the new working environment”. The Cronbach’s α for situational tactics, content tactics and social tactics were 0.845, 0.892, and 0.896, respectively.

Employee Voice Behavior

At time T2, voice behavior was assessed with a two-dimensional scale developed by Liang et al, which is suitable for the Chinese context. The scale includes promotive voice behaviors (5 items) and prohibitive voice behaviors (5 items), which are reported by new employees.50 Sample items of promotive voice behaviors items such as “I actively propose new projects that will benefit our organization”, and prohibitive voice behaviors items such as “I dare to voice out opinions that might affect efficiency in the organization, even if that would embarrass others”. The Cronbach’s α for promotive voice and prohibitive voice were 0.899 and 0.875, respectively.

Servant Leadership

At time T2, this scale was developed by Liden’s 7-items scale, which is reported by the team leader.80 For example, “I give my subordinates freedom to deal with difficult problems in the best way they think”. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.701.

Team Innovation Performance

At time T2, this scale was measured with Janssen’s 9-items scale (2000).81 Team innovation performance is evaluated by the team leader. A sample item is “The team solves problems from a new perspective”. In this study, team innovation performance also showed good reliability with a Cronbach’s α of 0.897.

Controlling Variables

Due to the similar entry time and position of new employees, only employee gender and education were selected as control variables. In addition, the gender and education level of the leader were also taken as control variables at the team level.

Data Analysis

In this study, we used Mplus 7.0 and AMOS 22.0 for data analysis and hypothesis testing. First, a descriptive statistical method was used to analyze the basic demographic characteristics of the sample, and the Pearson correlation coefficient was used to examine the relationship between all variables. Second, two sets of Confirmatory Factor Analysis were performed to verify the validity of our measurement model at the individual level and team level. Then, we aggregate individual perceived situational tactics, content tactics and social tactics to the team level, and verify the convergent validity of organizational socialization. Finally, to test the hypothesized cross-level model, the Hayes multiple mediation method (bootstrap analysis=5000 times) was constructed.82 In addition, a Simple Slope test proposed by Aiken et al was conducted to analyze the effect of moderating variables at different levels (Mean±Standard deviations).83 All the data were analyzed with a significant level of p<0.05.

Results Analysis

Descriptive Analysis and Reliability Analysis

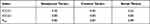

The means, standard deviations (SDs), correlation coefficients and reliability test values of all variables in this study are shown in Table 1. The results show that all the Cronbach’s α values (on the diagonal) are above 0.7, indicating that each variable has good internal consistency. In the correlation analysis, situational tactics, content tactics and social tactics are significantly positively correlated with promotive voice behavior (r=0.560, 0579, 0.630; p<0.01) and prohibitive voice behavior (r=0.542, 0.540, 0.603; p<0.01), respectively. They are also significantly positively correlated with team innovation performance (r=0.190, 0.247, 0.235; p<0.01). These results provide preliminary evidence to support our hypotheses in this study.

|

Table 1 Results of Descriptive Analysis and Reliability Analysis |

Measurement Model

Two sets of Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA) with AMOS 22.0 were conducted to test the validity of the individual-level scales and the team-level scales. At the individual level, we first estimated the proposed model with all latent variables (organizational socialization, promotive voice behavior, prohibitive voice behavior) into a model. The three-factor model had a good fit (X2/df =2.03, p<0.001, GFI=0.95, CFI=0.98, NFI=0.97, RMSEA=0.06). All the factor loadings were above the suggested threshold of 0.50 and were significant at the p <0.001 level. This result suggested that the scales had acceptable internal validity. Next, a two-factor model (combining promotive voice behavior and prohibitive voice behavior) was created to assess the distinctiveness of organizational socialization (X2/df =3.45, p<0.001, GFI=0.89, CFI=0.92, NFI=0.93, RMSEA=0.10). And one-factor model was also tested to estimate the discriminant validity (X2/df =5.51, p<0.001, GFI=0.86, CFI=0.91, NFI=0.90, RMSEA=0.13). At the team level, the CFA results indicated that the proposed model with two latent variables (servant leadership, team innovation performance) had a better fit (X2/df =2.53, p<0.001, GFI=0.89, CFI=0.92, NFI=0.86, RMSEA=0.07) than the one-factor model (X2/df =5.92, p<0.001, GFI=0.71, CFI=0.72, NFI=0.77, RMSEA=0.14). The results demonstrated that the model fit of the alternative models was poorer than that of the proposed factor model.

Convergent Validity

Since the organizational socialization variable was collected at the individual level, we need to aggregate situational tactics, content tactics and social tactics to the team level. The reliability of the ICC(1), ICC(2) and Rwg were calculated to test group variability and homogeneity. As seen from Table 2, the values of ICC(1), ICC(2) and Rwg of situational tactics, content tactics and social tactics were all greater than 0.7, 0.12 and 0.5, respectively. Therefore, situational tactics, content tactics and social tactics meet the aggregation criteria and can be analyzed at the team level.

|

Table 2 Results of Aggregation Test |

Tests of Hypotheses

In this study, cross-level structural equation models were developed using Mplus 7.0 to calculate the within-group effects and between-group effects. The Hayes multiple mediation method (bootstrap analysis=5000 times) was used to test the hypothesis.82 The results are shown in Table 3. In Model 1, after controlling for gender and education level of employees and their leaders, there was a positive relationship between organizational socialization and team innovation performance (β=0.376, p<0.01). Thus, H1 was supported. In Model 2, the coefficient between organizational socialization and promotive voice behavior was significant (β=0.594, p<0.001). In Model 3, the coefficient between organizational socialization and prohibitive voice behavior was also significant (β = 0.562, p<0.001). Thus, H2a and H2b were supported. Namely, H2 was supported. In Model 4, after entering the demographic variables and organizational socialization, the relationship between promotive voice behavior and team innovation performance was significant (β=0.417, p<0.001), as was the relationship between prohibitive voice behavior and team innovation performance (β=0.459, p<0.001). The results show that the path coefficients of organizational socialization and employee voice behavior, as well as voice behavior and team innovation performance were significant.

|

Table 3 Results of Cross-Level Structural Equation Model |

Furthermore, bootstrap analyses were also used to examine the indirect effect of organizational socialization on team innovation performance via employee voice behavior. A bootstrap sample (=5000 times) and a bias-corrected 95% confidence interval (CI) were examined. The results indicated that promotive voice behavior has a significant mediating effect between organizational socialization and team innovation performance (β=0.30, p<0.05, CI= [0.016, 0.585], excluding 0). Prohibitive voice behavior has a significant mediating effect between organizational socialization and team innovation performance (β=0.28, p<0.05, CI= [0.014, 0.546], excluding 0). Thus, H3a and H3b were supported, confirming that employee voice behavior mediated the effect of organizational socialization and team innovation performance.

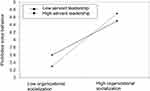

H4 proposed that servant leadership moderates the relationship between organizational socialization and employee voice behavior. We conducted Model 5 and Model 6 to test these proposals. As presented in Table 3, the interaction of organizational socialization and servant leadership was significantly related to prohibitive voice behavior (β=0.116, p<0.05); thus, H4b was supported. However, this interaction was insignificantly associated with promotive voice behavior (β=0.038, p>0.05). Thus, H4a was rejected. Moreover, to analyze the moderating effect of servant leadership at different levels (Mean ± 1SD), a Simple Slope test which proposed by Aiken et al was conducted.83 As shown in Figure 2, organizational socialization has a stronger positive effect on prohibitive voice behavior when servant leadership is at a higher level (Simple slope β = 0.687, p< 0.001). Meanwhile, organizational socialization has a weaker positive effect when servant leadership is at a lower level (Simple slope β = 0.455, p< 0.01).

|

Figure 2 The interactive effect of organizational socialization and servant leadership on prohibitive voice behavior. |

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to estimate the relationship between the organizational socialization of new employees and team innovation performance. The mediating role of employee voice behavior and the moderating role of servant leadership are also investigated. This study develops a cross-level structural equation model based on Social Information Processing Theory to test the above relationships. Through 2-stage matching data analysis, the following three findings are obtained in this paper.

First, our findings provide experimental evidence that the organizational socialization of new employees has a significant positive effect on team innovation performance. One logical explanation may be that organizations create a favorable climate for innovation by providing more organizational socialization tactics.5,84 This will contribute to the improvement of individual positive behaviors and further enhance team innovation performance.27,53 This finding is consistent with previous studies.48,66 Moreover, organizational socialization can help team members quickly establish formal and informal interpersonal networks32 so that new employees can obtain more organizational support. In turn, they will show a positive attitude and behavior towards the team and improve team innovation performance.25,26

Then, this study sheds light on the mediating role of employee voice behavior in the relationship between organizational socialization and team innovation performance. That is, organizational socialization is positively related to employee voice behavior, and employee voice behavior is positively related to team innovation performance. These findings are in line with previous studies, in which employees who perceived a higher level of organizational socialization showed more employee voice.53,85,86 A possible explanation for these results might be that when new employees perceive all kinds of organizational socialization tactics, they will gradually put forward proposals to the organization and share a large amount of their knowledge, opinions and experience.18 Accordingly, this effective advice obtained by team leaders from subordinates can help them build a good climate for team voice behavior to make the right decision, so as to improve team innovation performance.63,71

Finally, servant leadership has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between organizational socialization and prohibitive voice behavior. Previous studies have shown that servant leadership, as a moderating variable, can strengthen the positive relationship between organizational tactics and individual behaviors.51,74 Our findings are consistent with these studies. This means that servant leadership is helpful in forming a high-quality relationship and creating an inclusive environment.35,87 When new employees become members of the organization, highly socialized employees have stronger social network relationships, which provides favorable conditions for the voice behaviors among members.51,77,78 However, servant leadership has no significant moderating effect on the relationship between organizational socialization and promotive voice behavior. A possible explanation for this result might be that promotive voice behavior is different from prohibitive voice behavior. Compared with proposing innovative ideas and thoughts, it is obviously easier to call out current problems. That is, promotive voice behavior places higher demands on teams and employees. The relationship between organizational socialization and promotive voice behavior will not be affected regardless of the level of servant leadership.

Theoretical Implication

First, previous studies have shown that organizational socialization has a positive effect on individual behavior and organizational performance, such as job satisfaction, organizational identification, organizational commitment, but there has been little empirical research on the positive predictive relationship between organizational socialization and team-level outcomes.88,89 This study examines the impact of the organizational socialization of new employees on team innovation performance, which further enriches the empirical research on the organizational socialization. In addition, the current research on team innovation behavior is mainly based on Resource Exchange Theory, Social Learning Theory and Resource Conservation Theory, which has some limitations.90,91 This study has adopted the perspective of Social Information Processing Theory, which enriched the relevant theoretical achievements. Theoretically, socialization strategies such as normative learning, organizational acculturation and job skill training help new employees promote their adaptability to the organization, enhance organizational identity and establish a wide range of social connections with team members, which create an environment for innovative behaviors and improve team innovation performance. Therefore, this study not only expands the empirical research on the impact of organizational socialization on team-level outcomes but also enriches the understanding of the antecedents of team innovation performance.

Second, this study revealed that employee voice behavior played a cross-level mediating role between organizational socialization and team innovation performance. Based on the Social Information Processing Theory, new employees process all kinds of organizational socialization strategies, and gradually comply with organizational norms, cultural identity and internalization, thus realizing role transformation from an outsider to an insider of the organization.39 Employees with a high degree of organizational socialization tend to align their personal interests with the interests of the organization. When the organization encounters problems, they are more willing to put forward proposals to the organization and share a large amount of their personal knowledge, opinions and experiences. Therefore, these findings not only reveal the cross-level mechanism linking organizational socialization and team innovation performance but also provide a new theoretical perspective.

Third, some researchers have proposed that servant leadership is positively related to employee voice behavior.92 We use Social Information Processing Theory to extend this line of research. This study investigated the cross-level moderating effect of servant leadership on the relationship between organizational socialization and employee voice behavior, which further deepens the understanding of the organizational socialization. Our results revealed that organizational socialization has a stronger positive effect on prohibitive voice behavior when servant leadership is at a higher level. It means that servant leadership with humility, sincerity, and authorization is helpful to forming high-quality relationships and creating an inclusive environment, which enhances employees’ internal motivation and promotes positive behaviors. This finding not only provides a new theoretical perspective for exploring the boundary conditions of organizational socialization affecting employee voice behavior, but also enriches the theoretical research on servant leadership from the perspective of Social Information Processing.

Practical Implication

Research has shown that the strategies implemented by the organization significantly affect new employees’ attitudes, cognition and behavior, which are important antecedents of team outcomes. Therefore, this study offered several practical implications for newcomer management.

First, the results revealed that organizational socialization of new employees has a positive impact on team innovation performance. Enterprises need to pay more attention to constructing systematic organizational socialization strategies and carry out the implementation step by step according to the different stages when new employees join the team. For example, for new employees, the organization should strengthen the tactics of organizational regulations, organizational culture or job-related skills, while for new employees who have settled into their normal working life, the organization should focus more on the tactics of interpersonal relationships and job promotion.

Second, the cross-level results show that higher employee voice behavior can improve team innovation performance. Therefore, team leaders need to take measures to increase new employee voice behavior. In addition to the content tactics, situational tactics and social tactics, a fair and just organizational system should be established, and reasonable incentives should be adopted. Moreover, the organization needs to facilitate effective communication and cultivate friendly interpersonal relationship so that employees can feel the organizational support and identification.93 In such an organizational system, employees will have more voice behavior, and the possibility of improving team innovation performance is also higher.53

Third, team leaders should provide a series of support services to new employees, such as paying attention to their career development and strengthening communication and interaction. For example, in the team decision-making process, leaders should trust and respect new employees and give them full authority. At work, leaders should provide them with emotional support to satisfy their affiliation needs. These services would help to create a voice behavior friendly environment and further improve team innovation performance.

Limitations

Although the mechanism of the organizational socialization and team innovation performance was confirmed by the cross-level model, there are also several limitations to this study. First, based on the Social Information Processing Theory, the positive influence of organizational socialization on team innovation performance was demonstrated. In the future, other theories, such as Social Interaction Theory and Social Contagion Theory may be used to examine the relationship.94,95 Second, the employee voice behavior was selected as a mediating variable. To investigate the potential mediating effect, future research should examine other variables, such as organizational commitment, tacit knowledge sharing and other individual-level or team-level factors.96,97 Third, the moderating effect of servant leadership should be compared with other leadership styles, such as transformational leadership and platform leadership, to motivate individual voice behavior and increase team innovation performance. Last but not least, the sample size in this study was quite small. 352 employee questionnaires and 88 leader questionnaires were collected from innovative enterprises in China. Future research should examine whether such conclusions can be extended to other countries and cultures.

Conclusion

Drawing on Social Information Processing Theory, we proposed a cross-level model clarifying the mechanism and boundary of new employees’ organizational socialization influencing team innovation performance. We tested our research model with data from 352 new employees and 88 leaders using Mplus 7.0 and AMOS 22.0. Our results showed that the organizational socialization of new employees has a significant positive effect on team innovation performance. Both promotive and prohibitive voice behaviors play significant mediating roles between organizational socialization and team innovation performance. Additionally, servant leadership significantly moderates the relationship between organizational socialization and prohibitive voice behavior, but does not moderate the relationship between organizational socialization and promotive voice behavior.

Funding

This research was funded by the Project of Beijing Social Science (18GLC064, 19GLB025), National Natural Science Foundation of China Project (71801017, 71901031, 72002016) and Beijing Knowledge Management Institute.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Nifadkar SS, Bauer TN. Breach of belongingness: newcomer relationship conflict, information, and task-related outcomes during organizational socialization. J Appl Psychol. 2016;101(1):1–13. doi:10.1037/apl0000035

2. Lu SC, Tjosvold D. Socialization tactics: antecedents for goal interdependence and newcomer adjustment and retention. J Vocat Behav. 2013;83(3):245–254. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2013.05.002

3. Hart J. Global political economy: understanding the international economic order global political economy: understanding the international economic order. J Polit. 2003;65(1):264–265. doi:10.1111/1468-2508.00006

4. Vazifehdust H, Khosrozadeh S. The effect of the organizational socialization on organizational commitment and turnover intention with regard to moderate effect of career aspirations intention. Manag Sci Lett. 2014;277–286. doi:10.5267/j.msl.2013.12.027

5. Cooper-Thomas H, Anderson N. Newcomer adjustment: the relationship between organizational socialization tactics, information acquisition and attitudes. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2002;75(4):423–437. doi:10.1348/096317902321119583

6. Fang RL, Duffy MK, Shaw JB. The organizational socialization process: review and development of a social capital model. J Manag. 2011;37(1):127. doi:10.1177/0149206310384630

7. Song Z, Chathoth PK. Intern newcomers’ global self-esteem, overall job satisfaction, and choice intention: person-organization fit as a mediator. Int J Hosp Manag. 2011;30(1):119–128. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.03.003

8. Coldwell DAL, Williamson M, Talbot D. Organizational socialization and ethical fit: a conceptual development by serendipity. Pers Rev. 2019;48(2):511–527. doi:10.1108/PR-11-2017-0347

9. Nasr MI, El Akremi EA, Coyleshapiro J. Synergy or substitution? The interactive effects of insiders‘ fairness and support and organizational socialization tactics on newcomer role clarity and social integration. J Organ Behav. 2019;40(6):758–778. doi:10.1002/job.2369

10. de Vos A, Buyens D, Schalk R. Psychological contract development during organizational socialization: adaptation to reality and the role of reciprocity. J Organ Behav. 2010;24(5):537–559. doi:10.1002/job.205

11. Zhang Y, Yongzhou LI, Zhou Y, Zou Q. The mechanism of newcomer organizational socialization process from perspective of relationship resource. Adv Psychol Sci. 2018;26(4):584–598. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2018.00584

12. Moura G, Abrams D, Retter C, Gunnarsdottir S, Ando K. Identification as an organizational anchor: how identification and job satisfaction combine to predict turnover intention. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2010;39(4):540–557. doi:10.1002/ejsp.553

13. Gautam T, Dick RV, Wagner U. Organizational identification and organizational commitment: distinct aspects of two related concepts. Asian J Soc Psychol. 2004;7(3):301–315. doi:10.1111/j.1467-839X.2004.00150.x

14. Ge J, Su X, Yan Z. Organizational socialization, organizational identification and organizational citizenship behavior:an empirical research of Chinese high-tech manufacturing enterprises. Nankai Bus Rev. 2010;1(2):166–179. doi:10.1108/20408741011052573

15. Adil A, Kausar S, Ameer S, Ghayas S, Shujja S. Impact of organizational socialization on organizational citizenship behavior: mediating role of knowledge sharing and role clarity. Curr Psychol. 2021;1:1–9. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-01899-x

16. Slattery JP, Selvarajan TT, Anderson JE. Influences of new employee development practices on temporary employee work-related attitudes. Hum Resour Dev Q. 2006;17(3):279–303. doi:10.1002/hrdq.1175

17. Kelley SW. Developing customer orientation among service employees. J Acad Market Sci. 1992;20(1):27–36. doi:10.1007/BF02723473

18. Bauer TN, Bodner T, Erdogan B, Truxillo DM, Tucker JS. Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: a meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(3):707–721. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.707

19. Chen Y, Liu P. The information seeking behavior and organizational socialization among “Porcelain Bowl” staff: a moderated mediation model. J Forecast. 2019;38:31–37. doi:10.11847/fj.38.2.31

20. He H, Huang Y. How organizational socialization tactics affects millennial newcomer adjustment: a moderating effect of proactive behavior and newcomer identity. Chin J Manag. 2015;12:1457–1464. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-884x.2015.10.007

21. Kim TY, Cable DM, Kim SP. Socialization tactics, employee proactivity, and person-organization fit. J Appl Psychol. 2005;90(2):232–241. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.232

22. Xu X, Huang Y, Wu Z. The influence of organizational socialization strategy on new employee individual-organization matching-Mediating effect of active socialization behavior. J S China Normal U S. 2018;3:65–73.

23. Yang C, Wang Y, Guo N, Zhang H. A study on the mechanism of the impact of organizational socialization tactics on knowledge sharing in employees’ adaptation period: the mediating effect of organizational fit. Hum Resour Dev C. 2018;25:19–26. doi:10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2018.01.002

24. Luo J, Hu W, Zhong J. The dual path influence mechanism of ambidextrous leadership on newcomer socialization and innovative behavior. Sci Sci Manag S. 2016;37:161–173.

25. Ali A, Bahadur W, Wang N, Luqman A, Khan AN. Improving team innovation performance: role of social media and team knowledge management capabilities. Technol Soc. 2020;61:101259. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101259

26. Deng X, Wang Y. Theoretical discussion about the influence of dynamic team environment on venture team innovation and the mechanism. Sci Manag Res. 2019;37:21–23. doi:10.19445/j.cnki.15-1103/g3.2019.02.005

27. Sun H, Teh P-L, Ho K, Lin B. Team diversity, learning, and innovation: a mediation model. J Comput Inform Syst. 2016;57(1):22–30. doi:10.1080/08874417.2016.1181490

28. Lei S, Qin C, Ali M, Freeman S, Shi-Jie Z. The impact of authentic leadership on individual and team creativity: a multilevel perspective. Leadersh Org Dev J. 2021;42:644–662. doi:10.1108/LODJ-12-2019-0519

29. Maanen JV, Schein EH. Toward a theory of organizational socialization. Working papers. 1, 163–185. In: Staw BM, editor. Res Organ Behav. Vol. 1. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1979:209–264. doi:10.1108/S2046-410X(2013)0000001006

30. Salancik GR, Pfeffer J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Admin Sci Q. 1978;23(2):224. doi:10.2307/2392563

31. Kim K, Moon HK. How do socialization tactics and supervisor behaviors influence newcomers’ psychological contract formation? The mediating role of information acquisition. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2019;1–27. doi:10.1080/09585192.2018.1521460

32. Wen B. The role of social networks in open innovation: an empirical analysis. Mod Inform. 2017;37:68–74. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1008-0821.2017.09.010

33. Atan JB, Mahmood NHN. The role of transformational leadership style in enhancing employees’ competency for organization performance. Manag Sci Lett. 2019;2191–2200. doi:10.5267/j.msl.2019.7.033

34. Shafait Z, Yuming Z, Sahibzada UF. Emotional intelligence and conflict management: an execution of organizational learning, psychological empowerment and innovative work behavior in Chinese higher education. Middle East J Manag. 2021;8(1):1–22. doi:10.1504/MEJM.2021.111988

35. Lan Y, Qu X, Xia N. The influence of servant leadership on employee creativity: the mediating role of knowledge sharing behavior and the moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Hum Resour Dev C. 2020;37:37–49. doi:10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2020.11.003

36. Vancouver JB, Tamanini KB, Yoder RJ. Using dynamic computational models to reconnect theory and research: socialization by the proactive newcomer as example. J Manag. 2010;36(3):764–793. doi:10.1177/0149206308321550

37. Saks AM, Gruman JA. Manage employee engagement to manage performance. Ind Organ Psychol. 2011;4(2):204–207. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9434.2011.01328.x

38. Jones GR. Psychological orientation and the process of organizational socialization: an interactionist perspective. Acad Manage Rev. 1983;8(3):464–474. doi:10.5465/amr.1983.4284600

39. Gruman JA, Saks AM, Zweig DI. Organizational socialization tactics and newcomer proactive behaviors: an integrative study. J Vocat Behav. 2006;69(1):90–104. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2006.03.001

40. Huang S, Chen J, Mei L, Mo W. The effect of heterogeneity and leadership on innovation performance: evidence from university research teams in China. Sustainability. 2019;11(6):4441. doi:10.3390/su11164441

41. Ashforth BE, Sluss DM, Saks AM. Socialization tactics, proactive behavior, and newcomer learning: integrating socialization models. J Vocat Behav. 2007;70(3):447–462. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2007.02.001

42. Afshan G, Kashif M, Khanum F, Khuhro MA, Akram U. High involvement work practices often lead to burnout, but thanks to humble leadership. J Manag Dev. 2021;40(6):503–525. doi:10.1108/jmd-10-2020-0311

43. Harkins SG. Mere effort as the mediator of the evaluation-performance relationship. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91(3):436–455. doi:10.1111/1468-2508.00006

44. Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge U Press; 1991. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511815355

45. Choi Y. New employee socialization: the roles of social networks. Acad Manag Ann. 2014;1:12218. doi:10.5465/AMBPP.2014.12218abstract

46. Amabile TM, Conti R, Coon H, et al. Assessing the work environment for creativity. Acad Manag J. 1996;39(5):1154–1184. doi:10.2307/256995

47. Sarros JC, Woodman DS. Leadership in Australia and its organizational outcomes. Leadersh Org Dev J. 1993;14(4):3–9. doi:10.1108/01437739310039424

48. Khazanchi S, Lewis MW, Boyer KK. Innovation-supportive culture: the impact of organizational values on process innovation. J Oper Manag. 2007;25(4):871–884. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2006.08.003

49. Dyne LV, Ang S, Botero IC. Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. J Manag Stud. 2003;40(6):1359–1392. doi:10.1111/1467-6486.00384

50. Liang J, Farh CIC, Farh JL. Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: a two-wave examination. Acad Manag J. 2012;55(1):71–92. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.0176

51. Detert JR, Burris ER. Leadership behavior and employee voice: is the door really open? Acad Manag J. 2007;50(4):869–884. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2007.26279183

52. Dutton JE, Ashford SJ, Lawrence KA, Miner-Rubino K. Red light, green light: making sense of the organizational context for issue selling. Organ Sci. 2001;13(4):355–369. doi:10.1287/orsc.13.4.355.2949

53. Wu W, Tang F, Dong X, Liu C. Different identifications cause different types of voice: a role identity approach to the relations between organizational socialization and voice. Asia Pac J Manag. 2014;32(1):251–287. doi:10.1007/s10490-014-9384-x

54. Yan H, Tu H, Li J. The definition, dimensionality and content of newcomer’s organizational socialization: a perspective from identity theory. Adv Psychol Sci. 2011;19(5):624–632. doi:10.1111/j.1759-6831.2010.00112.x

55. Xu G, Huang Y, Tan L. Interactional justice and employee sharing hiding behavior: the mediating role of organizational identification and the moderating role of justice sensitivity. China Soft Sci. 2015;1:125–132. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-9753.2020.z1.016

56. Ashford SJ, Rothbard NP, Piderit SK, Dutton JE. Out on a limb: the role of context and impression management in selling gender-equity issues. Admin Sci Q. 1998;43(1):23. doi:10.2307/2393590

57. LePine JA, Van Dyne L. Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: evidence of differential relationships with Big Five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(2):326–336. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.2.326

58. Burris ER, Detert JR, Chiaburu DS. Quitting before leaving: the mediating effects of psychological attachment and detachment on voice. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(4):912–922. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.93.4.912

59. Savino T, Messeni Petruzzelli A, Albino V. Teams and lead creators in cultural and creative industries: evidence from the Italian haute cuisine. J Knowl Manag. 2017;21(3):607–622. doi:10.1108/jkm-09-2016-0381

60. Morrison EW. Employee voice behavior: integration and directions for future research. Acad Manag Ann. 2011;5(1):373–412. doi:10.1080/19416520.2011.574506

61. Edmondson AC. Speaking up in the operating room: how team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. J Manag Stud. 2003;40(6):1419–1452. doi:10.1111/1467-6486.00386

62. Zhou J, George JM. When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: encouraging the expression of voice. Acad Manag J. 2001;44(4):682–696. doi:10.2307/3069410

63. Xie XY, Ling CD, Mo S-J, Luan K. Linking colleague support to employees’ promotive voice: a moderated mediation model. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132123. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132123

64. Liu X, Chen C. The effect of team motivational climates on team creativity: from a perspective of the motivated information processing in groups model. Sci Sci Manag S. 2017;38:170–180.

65. Vegt GSVD, Bunderson JS. Learning and performance in multidisciplinary teams: the importance of collective team identification. Acad Manag J. 2005;48(3):532–547. doi:10.2307/20159674

66. Guo A, Ye C. Research on the influence of team learning on innovation performance under regulation of motivation. Sci Technol Manag. 2018;38:224–231. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-7695.2018.12.031

67. Cheng J, Lu K, Chang Y, Johnstone S. Voice behavior and work engagement: the moderating role of supervisor-attributed motives. Asia Pac J Hum Resou. 2013;51(1):81–102. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7941.2012.00030.x

68. Xu L. Boundary spanning behavior, team trust and Team innovation performance: mediation effect of resource depletion. Sci Technol Prog. 2019;36:11–18. doi:10.6049/kjjbydc.2018100115

69. Agrell A, Gustafson R. The Team Climate Inventory (TCI) and group innovation: a psychometric test on a Swedish sample of work groups. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1994;67(2):143–151. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1994.tb00557.x

70. Lin SHJ, Johnson RE. A suggestion to improve a day keeps your depletion away: examining promotive and prohibitive voice behaviors within a regulatory focus and ego depletion framework. J Appl Psychol. 2015;100(5):1381–1397. doi:10.1037/apl0000018

71. Li AN, Liao H, Tangirala S, Firth BM. The content of the message matters: the differential effects of promotive and prohibitive team voice on team productivity and safety performance gains. J Appl Psychol. 2017;102:1259–1270. doi:10.1037/apl0000215

72. Avery DR, Quiñones MA. Disentangling the effects of voice: the incremental roles of opportunity, behavior, and instrumentality in predicting procedural fairness. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(1):81–86. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.81

73. van Dierendonck VD, Nuijten I. The servant leadership survey: development and validation of a multidimensional measure. J Bus Psychol. 2011;26(3):249–267. doi:10.1007/s10869-010-9194-1

74. Lu J, Zhang Z, Jia M. Does servant leadership affect employees’ emotional labor? A social information-processing perspective. J Bus Ethics. 2019;159:507–518. doi:10.1007/s10551-018-3816-3

75. Rogers DP. Crucial decisions: leadership in policymaking and crisis management. Acad Manag Rev. 1989;15(3):542. doi:10.2307/258025

76. Volmer J, Spurk D, Niessen C. Leader–member exchange (LMX), job autonomy, and creative work involvement. Leadersh Q. 2012;23(3):456–465. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.10.005

77. Tan X, Liu B. Servant leadership, psychological ownership, and voice behavior in public sectors: moderating effect of power distance orientation. J Shanghai Jiaotong. 2017;25:49–58. doi:10.13806/j.cnki.issn1008-7095.2017.05.006

78. Duan J, Zeng K, Yan H. Dual mechanism of servant leadership affecting employee voice behavior. Chin J Appl Psychol. 2017;23:210–220.

79. Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

80. Liden RC, Wayne SJ, Meuser JD, Hu J, Wu J, Liao C. Servant leadership: validation of a short form of the sl-28. Leadersh Q. 2015;26(2):254–269. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.12.002

81. Janssen O. Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behavior. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2000;73:290–293. doi:10.1348/096317900167038

82. Hayes A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J Educ Meas. 2013;51(3):335–337. doi:10.1111/jedm.12050

83. Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions-institute for social and economic research. Eval Pract. 1991;14(2):167–168. doi:10.2307/2583960

84. Perrot S, Bauer TN, Abonneau D, Campoy E, Erdogan B, Liden RC. Organizational socialization tactics and newcomer adjustment. Group Organ Manag. 2014;39(3):247–273. doi:10.1177/1059601114535469

85. Rasheed MA, Shahzad K, Conroy C, Nadeem S, Siddique MU. Exploring the role of employee voice between high–performance work system and organizational innovation in small and medium enterprises. J Small Bus Enterp D. 2017;24(4):670–688. doi:10.1108/jsbed-11-2016-0185

86. Guo Y. A study on the influence of new employees’ organizational socialization on voice behavior: the mediating role of organization identification. Cont Ec Manag. 2017;39(2):73–77. doi:10.13253/j.cnki.ddjjgl.2017.02.013

87. Song C, Lee CH. The effect of service workers’ proactive personality on their psychological withdrawal behaviors: a moderating effect of servant leadership. Leadersh Org Dev J. 2020;41(5):653–667. doi:10.1108/LODJ-04-2019-0149

88. Wang Y, Lin G, Yang Y. Organizational socialization and employee job performance: an examination on the role of the job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

89. Hong G, Wang J. A study on Effects of organizational socialization on organizational identification and voice behavior—the moderating effect of traditionality.

90. Bandura A. Social learning theory. Scotts Valley Califo. 1977;1(1):33–52. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5614-7_3246

91. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44:513–524. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.44.3.513

92. Yang C, Zhang W, Wu S, Kee DMH, Liu P, Deng H. Influence of chief executive officer servant leadership on middle managers’ voice behavior. Soc Behav Pers. 2021;49(5):1–13. doi:10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2018.01.002

93. Dutton JE, Dukerich JM, Harquail CV. Organizational images and member identification. Admin Sci Q. 1994;39(2):239–263. doi:10.2307/2393235

94. Becker GS. A theory of social interactions. J Polit Econ. 1974;82(6):1063–1093. doi:10.1086/260265

95. Burt RS. Social contagion and innovation: cohesion versus structural equivalence. Am J Sociol. 1987;92(6):1287–1335. doi:10.1086/228667

96. Zhao D, Tian F, Sun X, Zhang D. The effects of entrepreneurship on the enterprises’ sustainable innovation capability in the digital era: the role of organizational commitment, person–organization value fit, and perceived organizational support. Sustainability. 2021;13:6156. doi:10.3390/su13116156

97. Miguel LAP, Popadiuk S. The semiotics of tacit knowledge sharing: a study from the perspective of symbolic interactionism. Cad EBAPE BR. 2019;17(3):460–473. doi:10.1590/1679-395172519x

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.