Back to Journals » Biologics: Targets and Therapy » Volume 9

Effect of mild aerobic training on the myocardium of mice with chronic Chagas disease

Authors Preto E, Lima N, Simardi L, Fonseca FLA, Filho AAF, Mesiano Maifrino LB

Received 23 March 2015

Accepted for publication 15 July 2015

Published 23 September 2015 Volume 2015:9 Pages 87—92

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/BTT.S85283

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Doris Benbrook

Emerson Preto,1 Nathalia EA Lima,1 Lucila Simardi,2 Fernando Luiz Affonso Fonseca,2,3 Abílio Augusto Fragata Filho,4 Laura Beatriz Mesiano Maifrino1,4

1Universidade São Judas Tadeu, São Paulo, 2Faculdade de Medicina do ABC, Santo André, 3Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Diadema, 4Instituto Dante Pazzanese de Cardiologia, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Background: Chronic chagasic heart disease represents extensive remodeling of the cardiovascular system, manifested as cardiac denervation, interstitial mononuclear infiltrate, myocyte and vascular degenerative changes, fibrosis, and hypertrophy. Moreover, aerobic exercises are widely indicated for the treatment of various disorders of the cardiovascular system.

Purpose: To evaluate the right and left ventricles of BALB/c mice with chronic Chagas disease, undergoing mild exercise, by using morphometric and stereological methods.

Materials and methods: A total of 20 male mice at 4 months of age were used for experiments. The animals were divided into four groups (n=5 in each group): untrained control, trained control, untrained infected (UI), and trained infected (TI). Animals of UI and TI groups were inoculated with 1,000 trypomastigote forms of Trypanosoma cruzi (Y strain), and after 40 days, animals entered chronic phase of the disease. Physical exercise, which included swimming, was performed for 30 minutes daily, five times a week for 8 consecutive weeks at a bath temperature of 30°C. After the trial period, euthanasia and subsequent withdrawal of the heart were done. The organ was prepared by histological staining procedures with hematoxylin–eosin and picrosirius red.

Results: We found that the physical training used in our experimental model promoted increase in volume density of capillaries and decrease in volume density of collagen fibers and cross-sectional area of cardiomyocytes in chagasic animals (TI group). By histopathological analysis, we found differences in the inflammatory infiltrate, which was lower in animals of TI group. The training program promoted a recovery of these parameters in the TI group.

Conclusion: Our results suggest that low-intensity aerobic exercise acts on morphological and morphometric parameters of the left and right ventricles in mice infected with T. cruzi, reducing the changes caused by the organism and making the results comparable to those of the uninfected control group.

Keywords: Chagas disease, myocardium, aerobic exercise, morphometry

Introduction

Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis, is a disease caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. It is found mainly in Latin America, from Chile to the Southern United States. In Brazil, it is the fourth leading cause of death from parasitic infection.1,2 According to the World Health Organization (WHO),3 over 12 million people are infected, and approximately 7–8 million are estimated to be infected worldwide, causing approximately 20,000 deaths annually. The main clinical manifestations of Chagas disease are cardiac and/or digestive disturbances.

Chronic chagasic heart disease represents extensive remodeling of the cardiovascular system, manifested as cardiac denervation and interstitial mononuclear infiltrate. Myocyte and vascular degenerative changes, fibrosis, and hypertrophy characterize the main pathologic features of chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy.1,3,4 These morphological alterations coexist and are associated with abnormalities of the electrical and contractile cardiac activities, which are characterized mainly by conduction faults, frequent and complex ventricular arrhythmias, and systolic ventricular dysfunction.5,6 In general, they are of ten biventricular pattern and frequent mode with greater impact on the right side, characterized by dilation and dysfunction of the right ventricle (RV), resulting from particular anatomical and functional changes of the left ventricle (LV) on the right side.7

Physical exercise is recognized as a hypotensive agent in both humans and animals,8,9,10 especially when training is carried out at low and moderate intensity, and acts as a powerful stimulus for the cardiovascular structural remodeling. Studies in animals and humans show positive results of physical exercise practice in the T. cruzi infection.11,12

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of an exercise program in the myocardium of mice with chronic chagasic heart disease, thus creating a basis for the practice of regular exercise as an additional medical therapy for this illness.

Materials and methods

Animals and procedures

Experimental animals

The study included 20 young, male, BALB/c mice (20–25 g, 5–7 weeks old) from the Animal House of the Dante Pazzanese Institute of Cardiology, São Paulo, Brazil. The animals were housed in collective polycarbonate cages in a temperature-controlled room (22°C) with a 12-hour dark–light cycle (light: 07:00–19:00 hours). Mice were fed standard laboratory chow. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee in Research of the São Judas Tadeu University (Proto 060/2007), and this investigation was conducted in accordance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care formulated by the National Institutes of Health. The mice were randomly assigned into four groups: untrained control (UC, n=5), trained control (TC, n=5), untrained infected (UI, n=5), and trained infected (TI, n=5).

Parasitemia and exercise training

Inoculum and strains of T. cruzi

Ten 20-day-old BALB/c mice (groups UI and TI) were infected with 1,000 trypomastigotes forms of Y strain of T. cruzi per animal. Parasites were obtained from the blood of infected mice, washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline by centrifugation, and inoculated intraperitoneally.

Parasitemia

Parasitemia curve and parasite peak were determined by collecting 5 μL of blood samples from the tail of the animal by using Brenner’s13 protocol. The blood was collected daily from the 2nd day of infection until no parasites were observed (~40 days), characterizing the chronic phase of infection.

Exercise training

After 60 days, all animals were adapted in a liquid medium in individual tanks (50 cm high × 30 cm diameter) for 5 days – 15 minutes daily – with the purpose of reducing the stress of animals when performing physical exercise in water. The training protocol, modified by Lancha Jr,14 included swimming and was performed with animals of TC and TI groups for 8 weeks, 5 days a week, lasting 30 minutes per day. There was no extra weight added to the training because of the animals’ fragility. The animals of the untrained groups (UC and UI) held a 15-minute session per week, intending to undergo the stress similar to that experienced by the trained animals. This protocol was characterized as training of low intensity and long duration.

Tissue sample preparation

At the end of the experiment, the animals (~120 days old) were sacrificed by decapitation, and an incision was made in their chests to expose the hearts of each animal. The hearts were removed and weighed on an analytical balance; then the atria were separated from the ventricles at the level of the atrioventricular groove, and the RV and LV were sectioned at the level of the papillary muscles, including the interventricular septum. The tissue thus obtained was weighed and fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution (pH 7.2) for 48 hours.

After fixation, the material was subjected to the process of dehydration, diafanization, and inclusion in paraffin. For every animal, five nonconsecutive histological sections, 6 μm thick cross sections, of the fragments of RV and LVwere used. After the hematoxylin–eosin and picrosirius red staining, the sections were examined by light microscopy and polarized light microscopy, respectively.

Morphological/morphometric analysis

The images were captured and used for morphometric and stereological studies with the AxioVision (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) software.

In total, ten images per group, under ×30 magnification, were captured. Four measures per image were obtained at 0°, 90°, 180°, and 270° to estimate the thickness of LV and RV. The area (a) of the left ventricular cavity was estimated by drawing a line over the circle delimited by the inner interface. The lumen diameter (D) was calculated as: D=2 v a/π.

A total of 480 photomicrographs (×400) were used for the quantitative analysis of the muscle tissue composition in LV and RV. The computerized program, AxioVision (Zeiss), analyzed each micrograph. The myocyte mean cross-sectional area (CSA [my]) was determined for every animal in each group. The myocardium was analyzed by a stereological test system with 442 points, which are delimited by lines of inclusion and exclusion, systematic and evenly allocated, and superimposed on the micrographs. The volume density was estimated for the myocyte (Vv [my]), capillaries (Vv [cap]), and connective tissue (Vv [ct]); Vv [structure] = PP [structure]/partial points (PP) counted on a section in relation to the total possible points or test-points (PT). To determine volume density of the picrosirius red-stained collagen fibers, the photomicrographs of the LV and RV were analyzed by using a stereological test system with 200 points, and values were expressed as a percentage.15

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM (standard error of mean). After confirming that all continuous variables were normally distributed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, statistical differences between the groups were obtained by one-way analysis of variance. When a significant difference was detected, comparisons were made by Tukey’s post hoc test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Biometrical analysis

The animals of the UI group showed a 24% decrease in the weight variation (initial weight–final weight, P<0.01) and physical training reversed this situation by 20% when compared to the control group (UC) (Table 1).

Histopathological analysis

The semiquantitative findings reveal differences between the groups and text, as shown in Figure 1.

Morphometric analysis

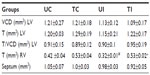

In the study groups, no significant difference was observed in the parameters such as thickness (T), diameter (D), and in the relation T/D in the LV. We observed a decrease (−6%) in the thickness of interventricular septum in the TI group when compared to that in the UI group. We noted that training caused a significant increase in the thickness of the right ventricular myocardium both in the control group (+24%) and the infected group (+66%) (Table 2).

When the myocardium of infected animals that did not undergo training (UI group) was analyzed and compared with that of the animals in the UC group), we found that the chronic Chagas disease promoted decrease (P<0.05) in the volume densities of capillaries and cardiomyocytes in the LV, and significant increase in the volume densities of collagen, interstitium, and the CSA of cardiomyocytes was observed. In the RV, we observed an increase (P<0.05) in the volume densities of collagen and capillaries and decrease in the interstitium and the CSA of cardiomyocytes (Table 3, Figures 1 and 2).

After performing the aerobic training protocol of low intensity, we found that exercising caused an increase in Vv [cap] (P<0.05) and a decrease in Vv [int], volume density of collagen fibers (Vv [col]), and CSA of cardiomyocytes (P<0.05) in infected animals, when compared to those in UI animals (Table 3, Figures 1 and 2).

Discussion

Our results showed that low-intensity aerobic exercise decreased the body weight to a little extent in the group of animals infected with T. cruzi. The decrease in body mass, associated with heart failure, caused by Chagas disease can characterize the cardiac cachexia. Perhaps, mild aerobic exercise training can promote improvements in this condition, which can be visualized by increased body mass.16

Besides the effect on body mass, the low-intensity aerobic exercise promoted thinning of the interventricular septum and increased the RV thickness. However, we found no differences in regard to the thickness and diameter, and in the relation between these parameters in the LV between the groups. The morphological reorganization of the parenchyma and stroma myocardium seems to be intrinsically induced as a result of the infection with T. cruzi. Novaes et al reported that such infection can induce an overall structural remodeling of the right atrium and LV in animals infected with T. cruzi.17 Furthermore, another study reported that remodeling occurs and the parasite infection may also compromise the tolerance to physical exercise.18 The positive effects of regular light aerobic exercise in patients with Chagas disease have been reported in the literature, Fialho et al found improvement of the cardiac functional capacity in these patients when they were subjected to regular physical exercise.19 Our results verified such effects on morphological and morphometric parameters. Debessa et al while studying the cardiac muscle tissue, especially collagen fibers, demonstrated that there are differences in the amount and types of collagen fibers between young and elderly subjects.20 The loss of cardiomyocytes is related to the accumulation of collagen. Another possible mechanism for the accumulation of collagen with age could be an inhibition of collagen degradation. Thus, the increase in myocardial collagen may contribute to the decrease of ventricular elasticity with age. Similar data were found by Marques et al in the myocardium of spontaneously hypertensive animals.21 Hypertension leads to hypertrophy in the cardiomyocytes, and the blood supply is affected; this in turn leads to ischemia and consequent cell loss by apoptosis and/or necrosis, promoting remodeling by reparative fibrosis.21

The present study showed changes in the chagasic untrained group (UI group) and similar data were observed by the aforementioned authors, corroborating our findings, which are as follows: cardiomyocyte hypertrophy is associated with 1) an increase in CSA [myo] (27%), perhaps to compensate the loss of cardiomyocytes; and 2) an increase in Vv [col] (106%) and Vv [ct] (77%) and decrease in Vv [cap] (41%), thus leading to an increase in the ratio. Tassi et al studied the relationship between fibrosis and ventricular arrhythmias in Chagas heart disease, without ventricular dysfunction, by cardiac magnetic resonance and found that the presence of myocardial fibrosis is closely related to arrhythmia. Furthermore, perhaps the parasitemia has a similar effect with advancing age and the effects of exercise on collagen fibers appear to be similar.22

Thus, we found that physical training used in our experimental model promoted increase in Vv [cap] and decrease in Vv [int], Vv [col], and CSA of cardiomyocytes in chagasic animals (TI group). In addition, the histopathological evaluation showed differences in the inflammatory infiltrate, which was lower in this group of animals. Similar results on the effects of physical exercise in chagasic animals were obtained in the enteric nervous system.23

The direct action of the parasitemia in the cardiac muscle in the above parameters was not reported in the literature. Finally, we note that our results suggest that the application of low-intensity physical training has positive effects on morphological and morphometric parameters of the LV and RV in mice infected with T. cruzi and minimizes the changes caused by the organism, making the results comparable to those of the uninfected control group. Further studies are needed to determine whether such activities can contribute to functional improvement of the heart muscle in the Chagas disease.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Biolo A, Ribeiro AL, Clausell N. Chagas cardiomyopathy – where do we stand after a hundred years? Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;52:300–316. | |

Rassi AJR, Rassi A, Marin-Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet. 2010;375:1388–1402. | |

World Health Organization. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs340/en/. Accessed September 15, 2014. | |

Marin-Neto JA, Cunha-Neto E, Maciel BC, Simões MV. Pathogenesis of chronic Chagas’ heart disease. Circulation. 2007;115:1109–1123. | |

Carod-Artal FJ, Vargas AP, Falcao T. Stroke in asymptomatic Trypanosoma cruzi-infected patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;31:24–28. | |

Carod-Artal FJ, Gascon J. Chagas disease and stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:533–542. | |

Simões MV, Almeida Filho OC, Pazin Filho A, Pereira RB, Schmidt A. Insuficiência cardíaca na doença de Chagas. Soc Cardiol Estado de São Paulo. 2000;1:50–64. | |

Morvan E, Lima NEA, Machi JF, et al. Metabolic, hemodynamic and structural adjustments to low intensity exercise training in a metabolic syndrome model. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12:89. | |

Chrysohoou C, Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Kokkinos PF, Stefanadis C, Toutouzas P. The association between physical activity and the development of acute coronary syndromes in treated and untreated hypertensive subjects. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2003;5:115–120. | |

Kokkinos PF, Narayan P, Papademetriou V. Exercise as hypertension therapy. Cardiology Clinics. 2001;19:507–516. | |

Schebeleski-Soares C, Occhi RC, De Moraes F, Marta SD, De Oliveira M, Almeida FN. Preinfection aerobic treadmill training improves resistance against Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2009;34:659–665. | |

Occhi RC, Soares CS, Franzói-De-Moraes SM, Batista MR, Kwabara HN, Sousa AMR. Infecção experimental pelo Trypanosoma cruzi em camundongos: influência do exercício físico versus linhagens e sexos. Ver Brás Méd Esp. 2012;18:51–57. | |

Brener, Z. Therapeutic activity and criterion of cure on mice experimentally infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1962:Nov-Dec;4:389–396. | |

Lancha Jr AH. Resistência ao esforço físico: efeito da suplementação nutricional de carnitina, aspartato e asparagina. São Paulo, 1991. Dissertação de Mestrado. Universidade de São Paulo, USP, Brasil. | |

Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Stereological tools in biomedical research. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2003;75:469–486. | |

Barbosa-Ferreira JM, Fernandes F, Dabarian A, Mady C. Leptin in heart failure. Expert Opin Med Diagn. 2013;7(1):113–117. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2013.735229. | |

Novaes RD, Penitente AR, Gonçalves RV, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi infection induces morphological reorganization of the myocardium parenchyma and stroma, and modifies the mechanical properties of atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes in rats. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2013;22(4):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2012.12.001. | |

Novaes RD, Penitente AR, Gonçalves RV, et al. Effects of Trypanosoma cruzi infection on myocardial morphology, single cardiomyocyte contractile function and exercise tolerance in rats. Int J Exp Pathol. 2011;92(5):299–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2011.00781.x. | |

Fialho PH, Tura BR, Sousa AS, et al. Effects of an exercise program on the functional capacity of patients with chronic Chagas’ heart disease, evaluated by cardiopulmonary testing. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012;45(2):220–224. | |

Debessa CRG, Maifrino LBM, Souza RR. Age related changes of the collagen network of the human heart. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122(10):1049–1058. | |

Marques CMM, Nascimento FAM, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA, Aguila MB. Exercise training attenuates cardiovascular adverse remodeling in adult ovariectomized spontaneously hypertensive rats. Menopause. 2006;13(1):87–95. | |

Tassi EM, Abramoff M, Nascimento EM, Pereira BB, Pedrosa RC. Relationship between fibrosis and ventricular arrhythmias in Chagas heart disease without ventricular dysfunction. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2014;102(5):456–464. | |

Moreira NM, Zanoni JN, de Oliveira Dalálio MM, de Almeida Araújo EJ, Braga CF, de Araújo SM. Physical exercise protects myenteric neurons and reduces parasitemia in Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Exp Parasitol. 2014;141:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2014.03.005. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.