Back to Journals » Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology » Volume 14

Effect of Disease Severity on the Quality of Life and Sense of Stigmatization in Psoriatics

Authors Kowalewska B , Jankowiak B, Cybulski M , Krajewska-Kułak E, Khvorik DF

Received 12 October 2020

Accepted for publication 5 January 2021

Published 2 February 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 107—121

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S286312

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Jeffrey Weinberg

Beata Kowalewska,1 Barbara Jankowiak,1 Mateusz Cybulski,1 Elżbieta Krajewska-Kułak,1 Dzmitry Fiodaravich Khvorik2

1Department of Integrated Medical Care, Medical University of Bialystok, Bialystok, Poland; 2Department of Dermatovenerology, Medical University in Grodno, Grodno, Belarus

Correspondence: Beata Kowalewska

Department of Integrated Medical Care, Medical University of Bialystok, 7A Curie-Skłodowskiej Str., Bialystok, 15-096, Poland

Tel +48 85 748 55 28

Email [email protected]

Introduction: Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the skin having a profound effect on the quality of life and contributing to the sense of stigmatization in the affected patients. The aim of this study was to analyze the effect of psoriasis severity on the quality of life and sense of stigmatization in psoriatics and to investigate relationships between these measures and sociodemographic variables.

Patients and Methods: The study included 111 patients with psoriasis. The inclusion criteria of the study were the diagnosis of psoriasis and written informed consent to participate. The study was based on a short survey prepared by the authors and four validated scales: Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), 6-item Stigmatization Scale, 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire, and Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI).

Results: Mean PASI score for the study group was 14 pts. Most respondents presented with low DLQI scores, with the mean value of 10.8 pts suggesting that the disease-related ailments were not extremely burdensome for the majority of the patients. Mean stigmatization scores for the 6- and 33-item scale were 7– 8 and 81– 82 pts, respectively.

Conclusion: The severity of psoriasis was the strongest determinant of the quality of life measured with the DLQI. Also, the levels of stigmatization determined with the 6- and 33-item scale correlated significantly with PASI scores.

Keywords: psoriasis, quality of life, stigmatization, psoriasis severity, psychodermatology, DLQI, PASI

Introduction

Chronic diseases of the skin with no doubt affect the quality of life of the patients. Psoriasis, an inflammatory, recurrent, and incurable dermatological disease, is a leading condition from this group. Psoriasis manifests with scaling skin lesions resulting from epidermal hyperproliferation. Aside from affecting the skin, the disease may also cause damage to the nails and joints, with psoriatic arthritis diagnosed in approximately every third patient with psoriasis.1 The prevalence of psoriasis is estimated at approximately 2% worldwide; also, in Poland, psoriatics constitute about 2–3% of the general population.2,3 Typical psoriatic lesions are well-demarcated patches with scales on top that heal entirely without leaving a scar. The lesions show a tendency to recur, involving previously unaffected skin or the same region as before, albeit with markedly higher severity.4 The development of psoriasis can be triggered by a plethora of extrinsic and intrinsic factors, among them genetic and immune predispositions, diet, some medications, infections, mechanical injuries, psychological stress, and traumatizing experiences.5–8

Social stigmatization is a specific problem experienced by psoriatics. Mass culture promoted via various media created the concept of a socially desirable body image. Hence, people strive for perfection in every aspect of their life, including physical appearance. Furthermore, a deviation from such an ideal body image may become socially unacceptable, and as a result, individuals who do not fit in are frequently socially marginalized. One reason behind the social exclusion may be the presence of dermatological pathologies, as healthy skin is considered a necessary attribute of the ideal body image. Many laypeople believe that all skin lesions are contagious, result from poor hygiene or inadequate care; this may eventually result in social exclusion and stigmatization of dermatological patients.9–14

Skin lesions being visible to others may stimulate aversion or disgust, which inevitably leads to social marginalization of affected persons. The social exclusion may frequently be a source of emotional problems in the patients, triggering depression and fear of stigmatization, disrupting their self-image, evoking the sense of being inferior, worthless, and unattractive.15–18 In turn, stress and negative emotions associated with the illness may cause exacerbation of skin lesions in a mechanism of emotional stimulation addressed previously by many researchers.15–20 Along with somatic ailments related to the primary disease, the psychosocial problems experienced by patients with psoriasis and other chronic dermatoses may eventually lead to the lack of illness acceptance, deterioration of the quality of life, and a whole spectrum of comorbidities, such as obesity, cardiovascular disorders, depression, substance abuse, to mention a few.19,21–29 Moreover, patients with chronic dermatoses were shown to present with various sexual disorders such as erectile problems, decreased libido and reluctance to have sex due to distorted body image and unpleasant experiences associated with the presence of skin lesions in the genital area.17,30–32

The aim of this study was to analyze the effect of psoriasis severity on the quality of life and sense of stigmatization in psoriatics.

Research hypothesis: Severity of psoriasis determines the quality of life and stigmatization level in patients with this disease.

Research question 1. Is an increase in psoriasis severity associated with a decrease in the quality of life of the patients?

Research question 2. Is an increase in psoriasis severity associated with an increase in the level of stigmatization associated with this dermatological disease?

Research question 3. Is a decrease in the quality of life associated with an increase in social stigmatization experienced by psoriatics?

Patients and Methods

Participants

The study included patients recruited at two private clinics of dermatology and medical cosmetology in Bialystok (Poland), headed by Prof. Wiaczesław Niczyporuk and Dr. Piotr Aleksiejczuk, respectively. The study group consisted of 111 patients with plaque psoriasis, among them 46.8% of women and 53.2% of men.

The inclusion criteria of the study were the presence of skin lesions typical for plaque psoriasis, duration of the disease longer than six months, and written informed consent to participate. Patients in remission, with the disease lasting less than six months and those who did not express their consent to participate were excluded from the study.

The study participants were recruited by experienced dermatologists who determined their PASI scores and recorded them in the patients’ documentation. Each respondent could withdraw from the study at any time without specifying the reason.

We reasoned that patients treated at randomly selected centers were representative for the entire population of Polish psoriatics. In the case of a widespread disease, such as psoriasis, patient’s decision to refer to a given center is primarily determined by the location of the latter in relation to one’s place of residence. We initially planned to enroll approximately 200 patients with plaque psoriasis. However, the enrollment period coincided with the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Poland, and hence, the target number of completed questionnaires could not be reached. Assuming some dropouts, a total of 200 patients were eventually recruited, but some respondents withdrew from the study after receiving the study questionnaire. Final response and rejection rates were 55.5% (n=111) and 44.5% (n=89), respectively.

The study was conducted in January and March 2020. The respondents received printed questionnaires along with the instructions on how to complete them. The responses were self-reported or filled in by an investigator, either at the clinic or home. The respondents who decided to complete the questionnaire at home were provided with a pre-addressed stamped return envelope. The research conformed with the Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and the procedures followed were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (concerning the ethical principles for the medical community and forbidding the release of the patient’s name and initials or the hospital evidence number). The study was reviewed and approved by the Local Bioethics Committee at the Medical University in Bialystok (decision no. R-I-002/285/2018).

Measures

The study was based on a short survey prepared by the authors, and four validated scales, among them three instruments measuring the impact of psoriasis: Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) developed by Finlay and Khan25 and adapted to Polish conditions by Szepietowski et al33 6-item Stigmatization Scale by Lu et al34 in Polish adaptation by Hrehorów et al35 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire by Ginsburg and Link36 in Polish version by Hrehorów et al35 and Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) by Fredriksson and Pettersson.37,38

Sociodemographic Survey

The survey prepared by the authors contained questions about sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents (gender, age, marital status, education, place of residence), the time elapsed since the diagnosis of psoriasis.

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

PASI is an objective measure which takes into account the severity of psoriatic lesions and the area affected, rather than subjective feelings of the patient. The result can range from 0 to 72 pts, with higher scores corresponding to more severe psoriasis. The results below 10 pts are interpreted as mild psoriasis, whereas the PASI scores of 10–50 pts and more than 50 pts correspond to moderate to severe and severe disease, respectively.38,39

Dermatology Life Quality Index

DLQI is the most commonly used instrument to measure the impact of skin diseases on the quality of life.25,33 The questionnaire refers to patient’s condition within a week preceding the study, in particular to disability and functional impairment caused by the dermatological disease, and to a lesser extent, to the emotional aspect of the condition (only 1 out of 10 items).25,33 The scale consists of 10 questions with the answers scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale: “very much” (3 pts), “a lot” (2 pts), “a little” (1 pt), and “not at all” (0 pts). The overall score can range between 0 and 30 pts. DLQI measures the negative impact of skin disease on the quality of life, and hence, the higher the score, the more deteriorated the quality of life in a given patient.25,33

6-Item Stigmatization Scale

The 6-item stigmatization scale consists of six single-choice questions, with the answers from “not at all”, to “sometimes”, “very often”, and “always” scored from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 pts (“always”). The overall score can range between 0 (lack of stigmatization) and 18 pts (maximum stigmatization level). The higher the score, the higher the level of stigmatization, rejection, and embarrassment associated with the dermatological disease.34,35

The Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire

The 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire consists of 33 single-choice questions, with the answers from “definitely yes”, to “yes”, “rather yes”, “rather no”, “no” and “definitely no” scored from 0 (“definitely no”) to 5 pts (“definitely yes”). The overall score can range from 0 (lack of stigmatization) to 165 pts (maximum stigmatization level). The higher the score, the stronger the sense of stigmatization in the respondent. Aside from the overall score, the instrument measures the levels of stigmatization in six domains: Anticipation of Rejection, Feeling of Being Flawed, Sensitivity to the Opinions of Others, Guilt and Shame, Positive Attitudes, and Secretiveness.35,36

Statistical Analysis

The results were subjected to statistical analysis with Statistica 7 package (StatSoft, Poland). Qualitative characteristics of the study group are presented as percentages, and quantitative variables are shown as descriptive statistics: arithmetic means, standard deviations, medians, lower and upper quartiles, minimum and maximum values. Statistical significance of between-group differences in the values of normally distributed variables was verified with Student’s t-test for two groups or analysis of variance (ANOVA) or its more advanced form, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for three and more groups. The relationships between two quantitative (ordinal) variables were interpreted based on Spearman’s coefficients of rank correlation (R) and relevant tests for statistical significance. The relationships between the quality of life, stigmatization, and other variables expressed on a ratio scale were determined based on Pearson’s coefficients of linear correlation. The effects of independent variables (eg, gender) on the values of numeric dependent variables were verified on regression analysis. The threshold of statistical significance for all analyses was set at p<0.05.39,40

Results

The respondents were divided into two age groups, 30 to 50 years (53.2%) and older than 50 years (46.8%). The largest proportion of the study participants (46.8%) completed secondary education, and every third respondent (33.3%) had higher education; the proportion of participants with primary or vocational education was 19.8%. The largest group of the respondents (55.9%) were married persons; the remaining 44.1% of the patients were singles, including 19 (17.1%) divorcees. The vast majority of the participants (82.9%) were city-dwellers. The largest occupational group were blue-collar workers (39.6%), followed by white-collar workers (29.7%) and retirement pensioners (19.8%). The remaining 10.8% of the participants who received a disability or unemployment benefits were farmers or students.

Duration of psoriasis in the study group varied considerably, from half a year to more than 50 years. However, based on the lower and upper quartile values, the majority of the participants were diagnosed with psoriasis within 4 to 20 years.

Only 1.8% of the respondents had never sought a dermatological consultation; nearly two-thirds (64.9%) visited their dermatologist whenever necessary (most likely in the case of the disease exacerbation), and one-third (33.3%) were seen by the physician regularly.

Emotional relationship of the respondents to their illness varied. The most common response to the diagnosis of psoriasis was astonishment (27%), followed by a sense of horrible stigma (17.1%), exhaustion (16.2%), indifference (14.4%), and considering the disease as a fate (12.6%). Some respondents were unable to specify their relationship to the illness.

PASI

Mean PASI score for the study group was 14 pts, with a median value of 11.3 pts (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Statistical Characteristics of Psoriasis Severity, Quality of Life and Stigmatization Levels Determined with the 6- and 33-Item Scale |

Psychometric Measures Associated with Psoriasis-Related Ailments

DLQI

Most respondents presented with relatively low DLQI scores, with the mean value of 10.8 pts suggesting that the disease-related ailments were not extremely burdensome for the majority of the patients. The individual DLQI scores ranged from 0 to 28 pts (Table 1).

Stigmatization Measured with the 6- and 33-Item Scale

Mean stigmatization scores for the 6- and 33-item scale were 7–8 and 81–82 pts, respectively (Table 1).

The largest proportion of the respondents scored 60–69 pts (16%), 70–79 pts (14%), or 90–95 pts (17%) on the 33-item scale (Figure 1A). The most frequently observed scores for the 6-item scale were 9–11 pts (24%), 3–5 pts (20%), and less than 3 pts (18%) (Figure 1B). The most common DLQI scores were 5–9 pts (25%), less than 5 pts (23%), and 10 to 14 pts (19%) (Figure 1C).

|

Figure 1 Distributions of the quality of life (C) scores and stigmatization levels determined with the 6- (B) and 33-item scale (A). |

Relationship Between the Severity of Psoriasis and the Psychometric Measures

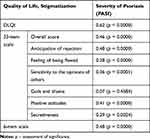

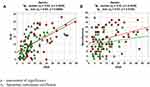

Analysis of correlations between PASI scores and the quality of life and stigmatization measures demonstrated that the severity of psoriasis exerted the strongest effect on the DLQI scores (R=0.62; p=0.0000). Also, the stigmatization levels measured with both scales (whether the overall scores or the scores for the domains of the 33-item scale) correlated significantly with PASI scores. However, these associations were weaker, with none of the correlation coefficients greater than 0.50. The only relationship which did not reach the threshold of statistical significance was the association between PASI scores and the score for the Guilt and Shame domain (R=0.07; p=0.4584) (Table 2). Correlations of PASI scores with DLQI (Figure 2A) values and overall scores for the 33-item scale are depicted as scatter plots (Figure 2B).

|

Table 2 Relationships of Psoriasis Severity with the Quality of Life and Stigmatization Levels (Spearman Correlation Coefficient) |

|

Figure 2 Distributions of DLQI scores (A) and overall scores for the 33-item scale (B) according to PASI. |

Relationship Between Demographic Factors and Quality of Life in Psoriasis

We verified if and to what extent demographic factors, such as gender, age, and education, as well as the duration of psoriasis, correlated with the quality of life measured with DLQI, and what was the relationship between the stigmatization levels and the severity of psoriasis.

Univariate Analysis

A significant relationship was found between gender and psoriasis severity (p=0.0082). The severity of psoriasis among women was significantly higher than in men (mean PASI scores of 16.6 and 11.6 pts, respectively). Moreover, women had significantly higher scores for the Secretiveness domain of the 33-item scale (p=0.0143). The effect of gender on the overall scores for both stigmatization scales was at a threshold of statistical significance (p-values below 0.10) (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Univariate Analysis. Relationships of Psoriasis Severity, Stigmatization and Quality of Life with Sociodemographic Variables |

Age of the respondents did not exert a significant effect on the severity of the disease (p=0.7017), quality of life in psoriasis (DLQI) (p=0.7230), and stigmatization levels (p=0.4446 and p=0.2975 for the 33-item and 6-item scale, respectively). However, visual inspection of the scatter plots suggested that respondents aged 31–50 years might present with more severe psoriasis, higher stigmatization levels, and lower quality of life (Table 3).

Education exerted significant effects on the quality of life in psoriasis (DLQI) (p=0.0212) and the scores for the two domains of the 33-item scale: Anticipation of Rejection (p=0.0413) and Feeling of Being Flawed (p=0.0197) (Table 3).

No statistically significant correlations were found between the duration of psoriasis, PASI scores, DLQI values, and stigmatization levels (Table 3).

Analysis of Covariance

Because the quality of life in psoriasis was shown to be affected by the severity of the disease, the effects of gender, age, and education on DLQI values were controlled for the PASI scores during the analysis of covariance. In the case of education and age, the analysis was carried out after stratification of the respondents into those with higher and non-higher education and those aged 31–50 years and older than 50 years, respectively.

After the results were controlled for PASI scores, gender no longer exerted a significant effect on the stigmatization levels. Only in the case of the scores for the Secretiveness domain of the 33-item scale, the relationship with gender was at a threshold of statistical significance, with men presenting with slightly lower (by 1.5 pts on average) stigmatization levels than women (p=0.0779) (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Effect of Selected Demographic Factors on Stigmatization Levels and Quality of Life After the Adjustment for Disease Severity (PASI Scores) – The Results of Covariance Analysis |

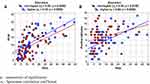

Regardless of the severity of psoriasis (PASI), no significant differences in DLQI values were found between male and female patients, with nearly identical regression lines for either gender (Figure 3A). In the case of the scores for the Secretiveness domain of the 33-item scale, visual inspection of scatter plots suggested that the effect of gender increased proportionally to the severity of psoriasis (Figure 3B).

|

Figure 3 Analysis of regression; relationships of the quality of life (A) and secretiveness (B) scores with PASI, stratified according to patient gender. |

As differences in disease severity might modulate relationships between demographic factors and quality of life, a series of additional covariance analyses (ANCOVA) were carried out with PASI score as a covariate. Table 4 contains information about the statistical significance of analyzed demographic factors in covariance models adjusted for PASI score (for simplicity, the results for PASI score, used only as a covariate, were not shown in the table; nevertheless, PASI score turned out to be a significant variable in all models). Most relationships that reached the threshold of statistical significance on univariate analysis were no longer significant after the adjustment for PASI scores (Table 4).

However, the PASI-controlled analysis of covariance identified also one statistically significant association. After controlling the results for the severity of psoriasis, patients with higher education presented with lower (by 1.5 pts on average) stigmatization scores for the Positive Attitudes domain of the 33-item scale, which implies that they had a more positive attitude to life than the respondents with non-higher education (Table 4).

The results for the analysis of the effects of education on the scores for the Positive Attitudes domain of the 33-item scale (Figure 4B) and DLQI values are depicted on scatter plots (Figure 4A).

|

Figure 4 Analysis of covariance; relationships of the quality of life (A) and positive attitudes (B) scores with patient education. |

Regression Analysis

The regression model including DLQI values as the outcome variable, and PASI score, gender, education (higher vs non-higher), age (31–50 years vs more than 50 years), and duration of psoriasis as independent variables was used. Also, interactions between PASI scores, gender, education, and age were considered during the regression analysis.

Except for PASI scores (p=0.0000), none of the independent variables and interactions turned out to be a significant predictor of the DLQI values (Table 5).

|

Table 5 Analysis of Regression. Relationships Between DLQI (Quality of Life) and Independent Variables – Results for Models with All Independent Variables |

Based on beta-values, the effect of PASI was the strongest in the case of DLQI. The DLQI values were not modulated significantly by any factor other than the severity of psoriasis. The severity of the disease explained approximately 35% of the variance in DLQI values (coefficient of determination calculated for a model with one significant predictor, PASI score). Based on the regression coefficient, each one-point increment in PASI score was associated with a 0.425-point increase in DLQI value, ie, with a deterioration of the quality of life.

Discussion

Skin plays multiple functions in the human body, among others, separating internal organs from the environment; this largest organ of the body is vital from a perspective of its esthetic perception. The symptoms of dermatological diseases are usually visible to others, which causes psychological discomfort of the patients, decreases their self-esteem and quality of life, and eventually, leads to social stigmatization.41

Mean PASI score for our study group was 14 pts, with median, minimum and maximum values of 11.3, 1.7, and 49.2 pts, respectively. The severity of psoriasis was significantly higher in women than in men, with mean PASI scores of 16.6 and 11.6 pts, respectively. In the study conducted by Kanikowska et al42 mean PASI score for 120 psoriatics was 15.2 pts (range 0.3–41.9 pts). In another study, carried out by Bronikowska-Kolasa et al43 in a group of 110 patients, PASI scores ranged from 1 to 27.3 pts, with the mean value of 12.7±5.6 pts corresponding to moderate to severe psoriasis. Jin et al44 followed 85 patients with psoriasis for six months of etanercept treatment, assessing their PASI 75/90 response at each visit. The study demonstrated that depression symptoms at the baseline were associated with worse clinical response to etanercept, as shown by reduced PASI 75/90 response rates.

A limitation of the PASI stems from the fact that this scale neither measures the effect of psoriasis on the quality of life nor considers subjective ailments reported by the patients.37,38 To overcome this limitation, aside from the PASI, we also used the Dermatology Life Quality Index, a scale measuring the impact of skin ailments on the quality of life.

The DLQI scores for our study group ranged from 0 to 28 pts, with a mean score of 10.8 pts. The scores for women were higher than for men (11.8 vs 10.0 pts.) In the study conducted by Kanikowska et al42, the DLQI values varied between 0 and 30 pts, with the mean result of 11.0 pts. Similar to our present study, those authors also found higher DLQI values in women than in men. Mean DLQI score for 161 psoriatics examined by Jung et al45 was 12.4 pts (SD=7.6), with 53.8% of the study participants showing a considerable deterioration of the quality of life. In the study carried out by Petraškienė et al8 a severe deterioration of the quality of life (DLQI ≥10 pts) was shown to be 1.8 times more likely among women than in men, and 2.7 times more likely in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis (PASI >10) than in those with mild disease (PASI ≤10).

In the study conducted by Sendrasoa et al among psoriatics from Madagascar,46 mean DLQI was 13.8 pts; deterioration in the quality of life was more evident in young patients, single persons, and those with medium level education. Importantly, an increase in PASI scores was associated with a significant deterioration of the quality of life in the study patients (p = 0.002). The effect of psoriasis severity on the quality of life in patients from Kuwait was analyzed by Al-Mazeedi et al47. The disease turned out to disrupt social relationships, sexual life, and physical activity of the respondents and deteriorated their quality of life.

Other authors, among them Sakson-Obada,48 demonstrated that gender is a significant moderator of the relationship between psoriasis and disturbances in several aspects of body self, and should be considered during a therapeutic intervention. Body self consists of three dimensions: function, representation, and body identity. The functions of body self include perception of experiences, interpretation thereof in terms of emotions and body needs, and finally, regulation. The second aspect of body self is representation, namely self-satisfaction with one’s body image and physical fitness, and acceptance of biological gender. Disease, especially the one associated with long-term physical discomfort and changes in body image, such as psoriasis, may cause significant disturbances in one’s body self with resultant aggravation of skin lesions. According to the literature, women are adjusted to their illness worse than men, assess their health-related quality of life lower,42,49 more often present with depression symptoms50 and regardless of the disease severity, suffer from higher levels of related stress.51 Women are also less satisfied with their physical appearance, with a substantial increase in this phenomenon observed in the second half of the 20th century.52,53 Clinical reports on the acceptance of gender-related body features suggest that women more often present with self-criticism and lack of satisfaction.54 Compared with men, women consider their appearance as more important component of self-image and self-esteem.50 All the gender-specific features mentioned above seem to be reflected by the severity of psoriasis and PASI scores in female and male patients.

In an American study conducted in 2002, 74% of psoriatics declared that the disease had a negative effect on their self-confidence at least often.55 According to Ginsburg et al36, the sense of stigmatization showed a strong correlation with bleeding from psoriatic lesions and was often associated with treatment non-compliance and resultant worsening of patient’s condition. Physicians are not infrequently concerned that the evaluation of patient’s quality of life may prolong the duration of control visits. Such an approach is unjustified given than in three out of four studies dealing with the problem in question, duration of the visits was the same, and in one increased by merely 0.5–2.7 min.36 The results of randomized studies analyzing the effect of information about patient’s quality of life on the treatment effectiveness and outcome are inconclusive. Some of those studies showed an improvement in both quality of life and emotional status of the patients. However, in other studies, the outcomes were similar as in patients whose physicians were kept ignorant about their quality of life. Perhaps, these discrepancies were associated with too short time allocated to the analysis of information obtained from patients, the use of an inappropriate method for quality of life assessment, insufficient education of physicians in terms of the use and interpretation of the quality life scales, or too short follow-up time. Regardless of their reason, the discrepancies mentioned above warrant further research on the problem in question, to identify appropriate methods for quality of life assessment in psoriasis, and to popularize the quality of life as a prognostic factor and/or outcome measure in the therapeutic process.56

Furthermore, the fact that psoriasis manifests periodically, and its exacerbations are separated by periods of nearly complete remission, may contribute to the lack of treatment compliance. Not infrequently, psoriatics tend to “forget” to follow a proper diet and lifestyle, quit smoking, and refrain from drinking alcohol; this eventually leads to exacerbation of the disease, complications, and resultant deterioration of the quality of life. Thus, education of patients is an inevitable component of the therapeutic process; noticeably, the patients should be provided not only with relevant knowledge, skills, and psycho-emotional motivation but also equipped with a set of new personal and moral values.

Not only the influence of psoriasis on the quality of life but also its effect on social stigmatization of the patients need to be emphasized. Not infrequently, the quality of life indices, the measures of disease severity and stigmatization levels correlate and modulate one another in psoriatics. It needs to be stressed that the quality of life is a highly subjective measure which depends not only on the underlying disease but also on the psychological condition of the patient.

The analysis of a relationship between PASI scores, quality of life, and stigmatization levels demonstrated that the severity of the disease was the strongest determinant of DLQI values in our patients (R=0.62). However, also the stigmatization levels measured with both questionnaires (either the overall scores or the scores for specific domains of the 33-item scale) correlated significantly with PASI. An increase in PASI by one point was associated with a 0.425-point increase in DLQI score, ie, with a deterioration in the quality of life. Vardy et al57 demonstrated that the severity of skin lesions expressed as PASI score correlated inversely with the quality of life in psoriatics, but not in the control group consisted of persons with mixed skin problems. Moreover, psoriatics presented with higher levels of stigmatization than the controls, which had an unfavorable effect on both severity of the disease and quality of life. Böhm et al58 examined 381 inpatients treated for psoriasis. Similar as in the study conducted by Vardy et al,57 presence of more severe symptoms was associated with greater discomfort, higher level of stigmatization, and worse quality of life.

Ginsburg et al36 identified characteristic traits of persons who experience stigmatization: sensitivity to others’ attitudes, the anticipation of rejection, lower self-esteem, feeling of being flawed, guilt and shame, and secretiveness.

In our present study, the stigmatization levels were shown to be significantly modulated by the gender and education of the respondents. Compared to men, women presented with significantly higher scores for the Secretiveness domain of the 33-item scale (p=0.0143*), and the gender-related differences in the overall scores for both stigmatization scales were at a threshold of statistical significance (p-values lesser than 0.10). Education exerted a significant effect on the scores for two domains of the 33-item scale: Anticipation of Rejection (p=0.0413) and Feeling of Being Flawed (p=0.0197). Moreover, patients with higher education presented with lower (by 1.5 pts on average) stigmatization scores for Positive Attitudes domain than the respondents with non-higher education. A stronger sense of stigmatization among women was previously reported by Zięciak et al11. Hawro et al13 and Schmid-Ott et al12 probably, this phenomenon should be linked to the fact that women pay more attention to their physical appearance than men. However, the effect of patient gender on the stigmatization was not confirmed by other authors, namely Kowalewska et al,59 Hrechorów et al,14 and Lu et al34. This, in turn, implies that the groups of patients examined by those authors might include a certain proportion of men who also followed current trends and strived for perfection in their body image. In the case of men, this tendency may be inter alia reflected by seeking professional cosmetology services to improve their physical appearance. In the study conducted by Böhm et al58 social consequences of psoriasis in female and male patients differed, but the effect of stigmatization on the quality of life in both groups was similar.

Because of impaired esthetic, communicative, and perceptive function of the skin, psoriatics are particularly sensitive about their appearance. As shown by Zacharie et al,23 Kowalewska et al,24 Türel Ermertcan et al,30 Hrehorów et al,35 and Zarek,60 dermatological diseases may have a profound impact on all areas of patients’ life, including occupational and social activities and interpersonal relationships. Dermatological patients have a sense of social stigmatization and rejection by others and suffer from deteriorated quality of life. Importantly, psoriasis may also negatively affect patients’ sexuality and make their partners avoid intimate contacts, as demonstrated by Dauendorffer et al31.

In the study conducted by van Beugen et al,61 up to 73% of psoriatics experienced stigmatization to some degree. Stigmatization turned out to be associated with lower education, higher disease visibility, severity and duration, higher levels of social inhibition, having a type D personality, and not having a partner.

Schmid-Ott et al62 followed-up a group of 166 psoriatics for one year; while the level of stigmatization in male patients correlated with actual condition of their skin, in women this parameter was also modulated by other, psychological factors.

In our present study, mean stigmatization scores obtained with the 6-item and 33-item scale were 7–8 and 81–82 pts, respectively. After the scores measured with the 6-item scale were transformed into an adjective scale, the study group was shown to consist predominantly of patients with low to moderate stigmatization levels (42.3% each), with persons with a strong sense of stigmatization constituting 15.4% of the sample. Presumably, this distribution of stigmatization scores reflected both the severity of psoriasis in the study group and individual experiences of the patients who presented with skin lesions being visible to others.

In the study conducted by Liasides et al63 9.8% of psoriatics did not experience stigmatization at all, and another 18.3% presented with minimum stigmatization levels measured with the 6-item scale; all other participants suffered from various degree of stigmatization. The analysis of the results obtained within the same group with the 33-item scale demonstrated that the primary domains in which the respondents experienced stigmatization were Anticipation of Rejection and Guilt and Shame.

A strength of this study stems from the fact that it analyzed the quality of life and stigmatization in psoriasis in relation to PASI scores, an objective measure of the disease-related ailments. However, it needs to be stressed that due to potential limitations, such as a relatively small sample size, the results of this study should be verified in a larger, more representative group of patients, and perhaps also expanded onto other areas, eg, to verify whether the location of skin lesions modulates the quality of life and stigmatization levels in psoriatics. Another potential direction of future research is a comparative analysis of the results obtained with the instruments used in this study in other groups of patients, eg, in persons before and after an anti-psoriatic treatment.

Conclusion

- The severity of psoriasis was the strongest determinant of the quality of life measured with the DLQI. Also, the levels of stigmatization determined with the 6- and 33-item scale correlated significantly with PASI scores.

- Gender exerted a significant effect on the disease severity, with significantly higher PASI scores found in women than in men. Moreover, women presented with significantly higher scores for Secretiveness domain of the 33-item scale.

- Duration of psoriasis did not exert a significant effect on PASI and DLQI scores and stigmatization levels.

- The education-related differences in DLQI values and stigmatization levels were not statistically significant when the results were controlled for PASI scores. Hence, lower quality of life and stronger sense of stigmatization observed in patients with university education seem to result from higher severity of psoriasis in this group.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics

Compliance with ethics guidelines: the protocol of the study was approved by the Local Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Bialystok. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in the survey.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Beata Kowalewska was a major contributor in writing the manuscript and supervised this study. Was responsible for patient recruitment, data collection, data analysis, and drafting the manuscript.

Barbara Jankowiak was a major contributor in writing the manuscript, was involved in the development of the idea, data analysis, and drafting the manuscript.

Dzmitry F. Khvorik was involved in the development of the idea and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Elżbieta Krajewska-Kułak was involved in the development of the idea and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Mateusz Cybulski was involved in the development of the idea and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Funding

This study and the Rapid Service Fee were funded by Medical University of Bialystok, Poland. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Neither honoraria nor other forms of payments were made for authorship.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. Hong J, Koo B, Koo J. The psychosocial and occupational impact of chronić skin disease. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:54–59. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00170.x

2. Inanir I, Aydemir O, Gündüz K, Danaci AE, Türel A. Developing a quality of life instrument in patients with psoriasis: the Psoriasis Quality of Life Questionnaire (PQLQ). Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:234–238. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02448.x

3. Kisielnicka A, Szczerkowska -dobosz A. Łuszczyca a otyłość - implikacje kliniczne. Dermatol Dypl. 2019;2:1–4.

4. Langner A, Ambroziak M, Stąpór W. Łuszczyca - etiopatogeneza i leczenie. Przewodnik Lekarza/Guide GPs. 2003;6(3).

5. Wolska H, Langner A. Łuszczyca. Lublin: Wyd. Czelej; 2006.

6. Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 2):ii18–ii23. doi:10.1136/ard.2004.033217

7. Jabłońska S, Chorzelski T. Choroby Skóry. Warszawa: PZWL; 2002.

8. Petraškienė R, Valiukevičienė S, Macijauskienė J. Associations of the quality of life and psychoemotional state with sociodemographic factors in patients with psoriasis. Medicina. 2016;52:238–243. doi:10.1016/j.medici.2016.07.001

9. Czykwin E. Stygmat Społeczny. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN; 2020.

10. Dimitrov D, Matusiak Ł, Szepietowski JC. Stigmatization in Arabic psoriatic patients in the United Arab Emirates - a cross sectional study. Adv Dermatol Allergol. 2019;36:425–430. doi:10.5114/ada.2018.80271

11. Zięciak T, Rzepa T, Król J, Żaba R. Stigmatization feelings and depression symptoms in psoriasis patients. Psychiatr Pol. 2017;51:1153–1163. doi:10.12740/PP/68848

12. Schmid-Ott G, Schallmayer S, Calliess IT. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis and psoriasis arthritis with a special focus on stigmatization experience. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:547–554. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.08.008

13. Hawro T, Janusz I, Zalewska A, Miniszewska J. Jakość życia i stygmatyzacja a nasilenie zmian skórnych i świądu u osób chorych na łuszczycę. In: Rzepa T, Szepietowski J, Żaba R, editors. Psychologiczne I Medyczne Aspekty Chorób Skóry. Wrocław Poland: Cornetis; 2011:42–51.

14. Hrehorów E, Salomon J, Matusiak Ł, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Patients with psoriasis feel stigmatized. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:67–72. doi:10.2340/00015555-1193

15. Zill JM, Dirmaier J, Augustin M, et al. Psychosocial distress of patients with psoriasis: protocol for an assessment of care needs and the development of a supportive intervention. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018;7:e22. doi:10.2196/resprot.8490

16. Kostyła M, Tabała K, Kocur J. Illness acceptance degree versus intensity of psychopathological symptoms in patients with psoriasis. Adv Dermatol Allergol. 2013;30:134–139. doi:10.5114/pdia.2013.35613

17. Hrehorów E, Reich A, Szepietowski J. Jakość życia chorych na łuszczycę: zależność od świądu, stresu i objawów depresyjnych. Dermatol Klin. 2007;9:19–23.

18. Martínez-Ortega JM, Nogueras P, Muñoz-Negro JE, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, González-Domenech P, Gurpegui M. Quality of life, anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with psoriasis: a case-control study. J Psychosom Res. 2019;124:109780. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109780

19. Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Psychiatric and psychological comorbidity in patients with dermatologic disorders: epidemiology and management. An J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4(12):833–842. doi:10.2165/00128071-200304120-00003

20. Fortune DG, Richards HL, Griffiths CE. Psychologic factors in psoriasis: consequences, mechanisms, and interventions. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23(4):681–694. doi:10.1016/j.det.2005.05.022.

21. Miękoś-Zydek B, Ryglewska A, Lassota-Falczewska M, Czyż P, Kaszuta A. Quality of life in psoriatic patients. Adv Dermatol Allergol. 2006;23(6):273–277.

22. Rapp DA, Brenes GA, Felman SR, et al. Anger and acne: implications for quality of life, patient satisfaction and clinical care. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(1):183–189. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06078.x

23. Zacharie R, Zacharie C, Ibsen H, Morternsen JT, Wulf HC. Dermatology life quality idem: data Danish inpatients and outpatients. Acta Derm Venerol. 2003;(suppl 2):78–86.

24. Kowalewska B, Krajewska-Kułak E, Wrońska I, Niczyporuk W, Sobolewski M. Self-assessment of quality of life in patients with dermatological disorders. Dermatol Klin. 2010;12(2):106–113.

25. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) – a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x

26. Gerdes S, Zahl VA, Weichenthal M, Mrowietz U. Smoking and alcohol intake in severely affected patients with psoriasis in Germany. Dermatology. 2010;220:38–43. doi:10.1159/000265557

27. Fortes C, Mastroeni S, Leffondré K, et al. Relationship between smoking and the clinical severity of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1580–1584. doi:10.1001/archderm.141.12.1580

28. Kirby B, Richards HL, Mason DL, Fortune DG, Main CJ, Griffiths CE. Alcohol consumption and psychological distress in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:138–140. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08299.x

29. Komorowska OR, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Purzycka-Bohdan D, Rawicz-Zegrzda D, Dudziak M. Łuszczyca jako czynnik ryzyka rozwoju chorób serca i naczyń. Przegl Dermatol. 2014;101:500–506.

30. Türel Ermertcan A, Temeltaş G, Deveci A, et al. Sexual dysfunction in patients with psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2006;33:772–778. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00179.x

31. Dauendorffer JN, Ly S, Beylot-Barry M. Psoriasis and male sexuality. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2019;146:273–278. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2019.01.021

32. Yang EJ, Beck KM, Sanchez IM, Koo J, Liao W. The impact of genital psoriasis on quality of life: a systematic review. Psoriasis. 2018;8:41–47. doi:10.2147/PTT.S169389

33. Szepietowski J, Salomon J, Finlay AY, et al. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): Polish version. Dermatol Klin. 2004;6(2):63–70.

34. Lu Y, Duller P, van der Valk PGM, Evers AWM. Helplessness as predictor of perceived stigmatization in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Dermatologie und Psychosomatik. 2003;4:146–150. doi:10.1159/000073991

35. Hrehorów E, Szepietowski J, Reich A, Evers AWM, Ginsburg IH. Narzędzia do oceny stygmatyzacji u chorych na łuszczycę: polskie wersje językowe. Derm Klin. 2006;8:253–258.

36. Ginsburg IH, Link BG. Feelings of stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:53–63. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(89)70007-4

37. Bożek A, Reich A. W jaki sposób miarodajnie oceniać nasilenie łuszczycy? Forum Derm. 2016;2(1):6–11.

38. Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis–oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica. 1978;157(4):238–244. doi:10.1159/000250839

39. Stanisz A. Przystępny Kurs Statystyki z Zastosowaniem STATISTICA PL Na Przykładach z Medycyny. Tom 1. Kraków: Wyd. StatSoft Polska; 2007.

40. Stanisz A. Przystępny Kurs Statystyki z Zastosowaniem STATISTICA PL Na Przykładach z Medycyny. Tom 2. Kraków: Wyd. StatSoft Polska; 2007.

41. Szepietowski J, Pacan P, Reich A, Grzesiak M. Psychodermatologia. Wrocław: Uniwersytet Medyczny im. Piastów Śląskich we Wrocławiu; 2015.

42. Kanikowska A, Michalak M, Pawlaczyk M. Zastosowanie oceny jakości życia chorych na łuszczycę w praktyce lekarskiej. Nowiny Lekarskie. 2008;77(3):195–203.

43. Bronikowska-Kolasa A, Szponar A, Maciąg J, Cielica W. Ocena wybranych aspektów jakości życia pacjentów z łuszczycą za pomocą kwestionariusza WHOQOL-100. Nowa Medycyna. 2008;3:4–11.

44. Jin W, Zhang S, Duan Y. Depression symptoms predict worse clinical response to etanercept treatment in psoriasis patients. Dermatology. 2019;235:55–64. doi:10.1159/000492784

45. Jung S, Lee M, Suh D, Shin HT, Suh DC. The association of socioeconomic and clinical characteristics with health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16:180. doi:10.1186/s12955-018-1007-7

46. Sendrasoa FA, Razanakoto NH, Ratovonjanahary V, et al. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis seen in the department of dermatology, Antananarivo, Madagascar. Biomed Res Int. 2020;14. doi:10.1155/2020/9292163.

47. Al-Mazeedi K, El-Shazly M, Al-Ajmi HS. Impact of psoriasis on quality of life in Kuwait. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(4):418–424. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02502.x.

48. Sakson-Obada O, Wycisk J, Pawlaczyk M, Gerke K, Adamski Z. Łuszczyca jako czynnik ryzyka dla zakłóceń w ja cielesnym – moderująca rola płci. Polskie Forum Psychologiczne. 2017;22(3):459–477.

49. Sampogna F, Chren MM, Melchi CF, Pasquini P, Tabolli S, Abeni D. Age, gender, quality of life and psychological distress in patients hospitalized with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:325–331. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06909.x

50. Wojtyna E, Łakuta P, Marcinkiewicz K, Bergler-Czop B, Brzezińska-Wcisło L. Gender, body image and social support: biopsychosocial deter minants of depression among patients with psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(1):91–97. doi:10.2340/00015555-2483

51. Finzi A, Colombo D, Caputo A, et al. Psychological distress and coping strategies in patients with psoriasis: the PSYCHAE Study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1161–1169. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02079.x

52. Feingold A, Mazzella R. Gender differences in body image are increasing. Psychol Sci. 1998;9(3):190–195. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00036

53. Brytek-Matera A. Obraz Ciała – Obraz Siebie. Wizerunek Własnego Ciała w Ujęciu Psychospołecznym. Warszawa: Difin; 2008.

54. Cross L. Body and self in feminine development: implications for eating disorders and delicate self-mutilation. Bull Menninger Clin. 1993;57(1):41–68.

55. Weiss SC, Kimball AB, Liewehr DJ, et al. Quantifying the harmful effect of psoriasis on health-related quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:512–518. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.122755

56. Guyatt GH, Ferrans CE, Halyard MY, et al. Jakość życia zależna od stanu zdrowia – od badań klinicznych do praktyki lekarskiej. Med Dypl. 2008;17:24–38.

57. Vardy D, Besser A, Amir M, Gesthaletr B, Biton A, Buskila D. Experiences of stigmatization play a role in mediating the impact of disease severity on quality of life in psoriasis patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(4):736–742. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04899.x

58. Böhm D, Stock Gissendanner S, Bangemann K, et al. Perceived relationships between severity of psoriasis symptoms, gender, stigmatization and quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(2):220–226. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04451.x

59. Kowalewska B, Cybulski M, Jankowiak B, Krajewska-Kułak E. Acceptance of illness, satisfaction with life, sense of stigmatization, and quality of life among people with psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Ther. 2020;10:413–430. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00368-w

60. Zarek A. Factors influencing body image in individuals with selected dermatological diseases. Ann Acad Med Stetin. 2014;60(1):75–87.

61. van Beugen S, van Middendorp H, Ferwerda M, et al. Predictors of perceived stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(3):687–694. doi:10.1111/bjd.14875

62. Schmid-Ott G, Künsebeck HW, Jäger B, et al. Significance of the stigmatization experience of psoriasis patients: a 1-year follow-up of the illness and its psychosocial consequences in men and women. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85(1):27–32. doi:10.1080/000155550410021583

63. Liasides J, Apergi FS. Predictors of quality of life in adults with acne: the contribution of perceived stigma. Eur Proc Social Behav Sci. 2015;1:2357. doi:10.15405/epsbs.2015.01.17.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.