Back to Journals » International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease » Volume 9 » Issue 1

Ease-of-use preference for the ELLIPTA® dry powder inhaler over a commonly used single-dose capsule dry powder inhaler by inhalation device-naïve Japanese volunteers aged 40 years or older

Authors Komase Y , Asako A, Kobayashi A, Sharma R

Received 15 August 2014

Accepted for publication 20 October 2014

Published 11 December 2014 Volume 2014:9(1) Pages 1365—1375

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S72762

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 5

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Russell

Yuko Komase,1 Akimoto Asako,2 Akihiro Kobayashi,3 Raj Sharma4

1Department of Respiratory Internal Medicine, St Marianna University School of Medicine, Yokohama City Seibu Hospital, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan; 2MA Respiratory Department, Development and Medical Affairs Unit, GlaxoSmithKline KK, Tokyo, Japan; 3Biomedical Data Sciences Department, GlaxoSmithKline KK, Tokyo, Japan; 4Global Respiratory Franchise Medical Department, GSK, Stockley Park, UK

Background: In patients receiving inhaled medication, dissatisfaction with and difficulty in using the inhaler can affect treatment adherence. The incidence of handling errors is typically higher in the elderly than in younger people. The aim of the study was to assess inhaler preference for and handling errors with the ELLIPTA® dry powder inhaler (DPI), (GSK), compared with the established BREEZHALER™, a single-dose capsule DPI (Novartis), in inhalation device-naïve Japanese volunteers aged ≥40 years.

Methods: In this open-label, nondrug interventional, crossover DPI preference study comparing the ELLIPTA DPI and BREEZHALER, 150 subjects were randomized to handle the ELLIPTA or BREEZHALER DPIs until the point of inhalation, without receiving verbal or demonstrative instruction (first attempt). Subjects then crossed over to the other inhaler. Preference was assessed using a self-completed questionnaire. Inhaler handling was assessed by a trained assessor using a checklist. Subjects did not inhale any medication in the study, so efficacy and safety were not measured.

Results: The ELLIPTA DPI was preferred to the BREEZHALER by 89% of subjects (odds ratio [OR] 70.14, 95% confidence interval [CI] 33.69–146.01; P-value not applicable for this inhaler) for ease of use, by 63% of subjects (OR 2.98, CI 1.87–4.77; P<0.0001) for ease of determining the number of doses remaining in the inhaler, by 91% for number of steps required, and by 93% for time needed for handling the inhaler. The BREEZHALER was preferred to the ELLIPTA DPI for comfort of the mouthpiece by 64% of subjects (OR 3.16, CI 1.97–5.06; P<0.0001). The incidence of handling errors (first attempt) was 11% with ELLIPTA and 68% with BREEZHALER; differences in incidence were generally similar when analyzed by age (< or ≥65 years) or sex.

Conclusion: These data, obtained in an inhalation device-naïve population, suggest that the ELLIPTA DPI is preferred to an established alternative based on its ease-of-use features and is associated with fewer handling errors.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dry powder inhaler, ELLIPTA®, BREEZHALER™

Introduction

Current treatment guidelines for chronic obstructive airways disease (COPD) recommend the use of long-acting bronchodilators to relieve symptoms and reduce exacerbations, and these therapies are commonly delivered using hand-held aerosol inhalers.1 Inhalers are the preferred mode of delivery as they allow the medication to be deposited directly into the lungs, thus reducing the chance of systemic adverse reactions.2

Patients with COPD are generally older than those with asthma; the risk of COPD increases five-fold in individuals over 65 years of age compared with those younger than 40 years of age.3 Patients with COPD are therefore more likely to have impaired dexterity and hence to make handling errors,4 and experience difficulties in achieving correct inhaler technique.5 A systematic review of inhaler use has shown that, depending on the type of inhaler, between 4% and 94% of patients do not use their inhalers correctly.2 The clinical effectiveness of inhaled medications may be compromised by suboptimal inhaler technique6,7 and dissatisfaction with the inhaler, which can result as a consequence of experiencing difficulty in using the inhaler correctly.8 Therefore, there is a need for inhalers that are easy to use correctly, thus ensuring successful drug delivery.

The ELLIPTA® multidose dry powder inhaler (DPI) (ELLIPTA is a trademark of the GSK group of companies) can hold sufficient medication for one month (30 doses) without having to replace cartridges or capsules. Separate multidose blister strips can also be used in the ELLIPTA DPI, allowing two separate drug formulations to be administered simultaneously. The ELLIPTA DPI is used to deliver once-daily combination therapies: the corticosteroid fluticasone furoate with the long-acting beta agonist vilanterol, a combination which is approved for COPD in the USA and Canada, for asthma in Japan, and for COPD and asthma in Europe; and the long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist umeclidinium with vilanterol, approved for COPD in the USA, Canada, Europe, Japan, and in several other countries.

The ELLIPTA DPI was designed to be easily operated by patients of all ages, including the elderly (>70 years), and a previous study demonstrated that it can be operated correctly by the majority of volunteers aged 20 years or older without previous experience of inhaler use and without verbal or demonstrative instruction.9 Using a self-completed questionnaire, these volunteers also reported that the inhaler was easy to operate.

BREEZHALER™ (BREEZHALER is a trademark of Novartis) is a single-dose capsule inhaler that delivers medication (indacaterol and glycopyrronium bromide) contained in a blister pack of capsules. The inhaler is prepared for use by tilting the mouthpiece open and placing a single capsule from the blister pack into the capsule chamber and closing the inhaler until a “click” is heard. The capsule is then pierced by pressing together both side buttons at the same time until a “click” is heard. The side buttons must then be released fully before the inhaler is ready for use.10 Previous research has shown that patients with COPD prefer the BREEZHALER over the HANDIHALER™ (Boehringer Ingelheim) DPI, which is commonly used in Japan for the delivery of COPD maintenance therapy.11 The BREEZHALER DPI was chosen as the comparator for the ELLIPTA DPI because BREEZHALER is the most recently introduced capsule DPI, was at the time of the study about to be introduced in Japan as the first inhaler available for long-acting beta agonist/long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist delivery, and shares similarities with the HANDIHALER DPI.

This study assessed inhaler preference and handling errors in inhalation device-naïve Japanese volunteers ≥40 years of age, a population in which these endpoints have not been assessed previously. The primary objective of the study was to compare preference for the ELLIPTA DPI versus the BREEZHALER DPI, based on ease-of-use criteria after two attempts to use each inhaler. A secondary objective was to determine the incidence of handling errors in the first and second attempts to use each inhaler. Handling errors were assessed before any demonstration or verbal instructions were given, an outcome that has not previously been evaluated.

Materials and methods

Design and subjects

This was a single-center, randomized, open-label, two-period crossover study of the ELLIPTA DPI versus the BREEZHALER DPI (control), conducted between November 19, 2013 and November 27, 2013 at Shiba Palace Clinic, Tokyo, Japan (GSK study number 200372). Male and female Japanese volunteers ≥40 years of age who were capable of giving written informed consent were eligible for the study. The clinic supplied study recruitment information to volunteers on their research panel who did not necessarily attend the clinic regularly. There were both healthy volunteers and volunteers who had one or more recorded diagnoses, since health status was not assessed as part of the study eligibility criteria. Though study subjects were not required to be healthy, those who had regularly used a DPI or who had any previous experience of using the BREEZHALER, HANDIHALER, or ELLIPTA DPI were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included any condition that affected the subject’s ability to operate the inhaler (eg, rheumatism, eye disorder, dementia, and finger disorder or injury).

Subjects aged 40–64 years and ≥65 years of age were enrolled into the study in a ratio of 1:2, and males and females in a ratio of 1:1. Subjects were stratified by sex and age, and randomized 1:1 to the two inhalers using the permutation block method (block size 4).

Treatment

Each subject was randomized to begin with one of two DPIs (ELLIPTA [GSK KK, Tokyo, Japan] or BREEZHALER [Novartis Pharma KK, Tokyo, Japan]) and to perform a sequence of assessments (Figure 1). The study was designed to assess the subjects’ technique and preference for inhaler use up until just before the point of inhalation. It was not designed to examine efficacy, so the inhalers were not loaded with any active treatment. After completing their first sequence of assessments, subjects then performed the sequence again using the other inhaler. Subjects used the two DPIs one after the other on the same day and in the order designated by the randomization procedure. Each subject was assessed by the same assessor through both sequences. All assessors underwent a standardized detailed training session in how to evaluate subjects’ handling of the inhalers.

| Figure 1 Study schema showing the crossover design and sequence of activities undertaken. |

The ELLIPTA DPI containing no blister strip was used for subject-reported assessment of inhaler operability and for subject assessment of inhaler mouthpiece comfort. For assessment of inhaler handling technique and unpacking, the ELLIPTA DPI with strips containing lactose monohydrate and magnesium stearate was used. Empty capsules were prepared for assessing the use of the BREEZHALER DPI.

All subjects were given two attempts to use each inhaler. The first attempt was made after reading the patient information leaflet. A trained assessor recorded any errors in technique using a pre-prepared checklist, which was based upon the patient information leaflet. Because different techniques are required to use the two inhalers, it was necessary to use a different checklist for each inhaler. A total of eight distinct errors were listed on the checklist for the BREEZHALER DPI, compared with six for the ELLIPTA DPI. After nonverbal demonstration of the correct technique by the assessor, a second attempt at using the inhaler was then made and the assessor again recorded any errors. Subjects who were not able to use the inhaler correctly even at the second attempt were provided with verbal handling instruction, and the mean time from start of handling instruction to acquiring ability to use was recorded. The subjects then crossed over to use the alternative inhaler and the same sequence of activities was performed.

After completion of the inhaler handling technique assessments for both inhalers, the subjects completed a questionnaire to determine inhaler preference. The questionnaire assessed subject preference according to a range of ease-of-use features, as summarized in the next section.

The subjects’ ability to remove the ELLIPTA DPI from the aluminum tray packaging was assessed and categorized as: could unpack without instruction, could unpack with instruction, or could not unpack with instruction. If the subject was unable to unpack without instruction, the assessor recorded the actual instruction given, and described what prevented the subject from opening the pack without instruction.

Outcome measurements

The primary outcome was the odds ratio of preference for ease-of-use between the ELLIPTA DPI and the BREEZHALER DPI. The secondary outcomes were the proportion of subjects with any handling error, proportion of subjects with each error, mean time from start of handling instruction to being able to use the inhaler, level of unpacking operation attained, and preference rates for ease of use, ease of knowing how many doses remain in the inhaler, comfort of mouth piece, handling steps, and handling time.

Statistical analysis

The target sample size was planned on the basis of statistical power to detect a significant difference in inhaler preference with 90% power, assuming a two-sided 5% significance level. Based on an a priori estimated odds ratio (OR) of preference for the ELLIPTA DPI over the BREEZHALER DPI ranging from 1.8 to 2.2, the required sample size ranged from 130 to 74 subjects.

A priori subgroup analyses according to age (<65 years old versus ≥65 years) and sex were conducted. Taking into account the age and sex subgroup analyses, a target total sample size of 150 subjects was sought to provide sufficient statistical power for detecting differential preference with an OR of approximately 2.

Any difference in ease of use between the ELLIPTA DPI and BREEZHALER DPI was determined by calculating the OR and 95% confidence interval (CI) of the number (percentage) of subjects with each answer, based on a logistic model that included sex, age, and sequence. Descriptive statistics were used to record the difference in time (minutes) from the start of the handling instruction to acquiring ability, and the percentage of subjects who were able to unpack the ELLIPTA DPI according to the three categories described above. SAS version 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

The full analysis set comprised all subjects who fulfilled the inclusion criteria, did not meet any of the exclusion criteria, provided consent, handled both inhalers, and had preference data.

Results

One hundred and fifty subjects were recruited and comprised the full analysis set. The mean (± standard deviation) overall age was 62.8±10.66 years. A total of 100 participants in the study were aged ≥65 years and there were equal numbers of male and female subjects (Table 1).

| Table 1 Age and sex of participants |

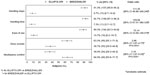

For “ease of use”, the ELLIPTA DPI was preferred over the BREEZHALER DPI by 134 versus 16 subjects, respectively (OR 70.14, 95% CI 33.69–146.01; P-value not applicable for this inhaler, Figure 2). The ELLIPTA DPI was preferred to the BREEZHALER DPI by 137 versus 13 subjects for the number of steps needed and by 139 versus 11 subjects for the time needed to operate the inhaler (Figure 2). The ELLIPTA DPI was preferred by 63% of all subjects for ease of knowing how many doses of medication are left in the inhaler (Figure 2). The BREEZHALER DPI was preferred over the ELLIPTA DPI for comfort of mouthpiece (96 versus 54 subjects, Figure 2). All of these observations were unchanged when the results were analyzed by age and sex (Figure S1).

| Figure 2 Overall subject preference for the ELLIPTA® DPI versus BREEZHALER™. |

Types of handling error observed at the first attempted use of the inhalers are shown in Table 2. Overall, the number of subjects with at least one error was lower with the ELLIPTA DPI (n=17 [11.3%], 95% CI 6.7–17.5) compared with the BREEZHALER DPI (n=102 [68.0%], 95% CI 59.9–75.4); (OR 16.62, 95% CI 9.03–30.61). The number of subjects with at least one error at the first attempt was also lower with the ELLIPTA DPI compared with the BREEZHALER DPI in both the age and sex subgroups (Table 3).

At the second attempt, after nonverbal demonstrative instruction, the overall number of handling errors was lower than at the first attempt for both the ELLIPTA DPI (n=3 [2.0%], 95% CI 0.4–5.7) and the BREEZHALER DPI (n=49 [32.7%], 95% CI 25.2–40.8; Table S1).

While using the BREEZHALER DPI, several subjects were reported to have replaced the cap after removing it, which occurred at around the timing of pressing the side buttons. Of these, eight subjects ultimately moved the BREEZHALER close to their mouth without removing the cap. Also using the BREEZHALER DPI, one subject was reported to have dropped a capsule three times. In the ELLIPTA DPI group, one subject moved the ELLIPTA DPI close to their mouth while holding it in a vertical orientation against the mouth.

For subjects who were unable to use the inhaler after two attempts (ELLIPTA DPI, n=3; BREEZHALER, n=49), the mean duration of handling instruction required to achieve correct use was shorter among those using the ELLIPTA DPI when compared with those using the BREEZHALER DPI (1.2 minutes versus 1.9 minutes, respectively). All subjects were able to open the aluminum tray containing the ELLIPTA DPI without instruction.

Discussion

Bronchodilators used to treat pulmonary diseases such as asthma and COPD are administered using inhalers. The ease of use of an inhaler is important in minimizing the likelihood of handling errors. Incorrect use of inhalers may result in diminished therapeutic effects, poor control of symptoms, and inadequate control of the disease resulting from suboptimal dosing,6 and can also give rise to patient dissatisfaction with the inhaler.8 Ease of use is therefore an important factor in encouraging patient persistence with therapy.7 Verbal instruction in inhaler use may support correct use of the inhaler,12 but is not applied consistently in clinical practice; it has been reported that up to 25% of patients never receive verbal instruction on inhaler technique.2 An inhaler that patients are able to use correctly with little or no verbal instruction is therefore desirable, but we recognize that patient education in inhaler use and reinforcement is important.

The findings of our study are consistent with previously reported data. In our study, the ELLIPTA DPI was preferred to the BREEZHALER DPI for ease of use, number of steps needed, and time taken to operate the inhaler by 89%, 91%, and 93% of the inhalation device-naïve subjects, respectively. In previously reported qualitative interviews of patients with COPD in the USA, 85%–95% preferred the ELLIPTA DPI to their current inhalers (DISKUS™ [GSK], HANDIHALER, or metered dose inhalers); among patients with asthma, 60%–71% preferred the ELLIPTA DPI to the DISKUS or metered dose inhaler.13 Subjects in our study also reported that they found the visual dose indicator of the ELLIPTA DPI to be helpful and clear. In a separate patient-reported ease-of-use study in patients with asthma participating in three multinational, randomized, controlled trials of fluticasone furoate/vilanterol combination therapy, 94% of participants reported that the ELLIPTA DPI was “easy or very easy to use”.14

The majority of subjects in our study preferred the BREEZHALER DPI over the ELLIPTA DPI for mouth piece comfort (64% versus 36%, respectively), which may reflect the differences in mouthpiece shape and size. The mouthpiece of the BREEZHALER DPI is larger than that of the ELLIPTA DPI, and some patients may find this more comfortable when forming a seal.

Our ease-of-use data for subjects <65 and ≥65 years of age was similar between groups. In the older subgroup, 87% of subjects preferred the ELLIPTA DPI to the BREEZHALER DPI on the basis of ease of use, compared with 94% of subjects in the younger group. The current study provides new evidence to support the preference for the ELLIPTA DPI by older subjects, which is important given that the incidence of COPD increases with age.

Handling errors were assessed using pre-prepared checklists designed to categorize all errors that could potentially be made by users of the ELLIPTA and BREEZHALER DPIs. Because the BREEZHALER DPI is more complex to use compared with the ELLIPTA DPI, more error categories were listed in the BREEZHALER checklist than that used for the ELLIPTA DPI (eight versus six). At first attempt, the proportion of subjects with at least one handling error was lower for the ELLIPTA DPI compared with the BREEZHALER DPI (11% versus 68%). At this attempt, the subjects had read the patient information leaflet, but had not received any verbal instruction and had no previous experience of DPI use. These results suggest that use of the ELLIIPTA DPI is simpler and more intuitive versus the BREEZHALER DPI. At the second attempt, after a nonverbal demonstration by the study assessor, the proportion of subjects with handling errors for the ELLIPTA DPI decreased from 11% to 2%; for the BREEZHALER DPI, the proportion decreased from 68% to 33%. A previous study, reporting the results of indepth interviews of asthma and COPD patients who had used the ELLIPTA DPI in clinical trials,13 showed that most patients felt that after a demonstration they did not need to refer to the instructions or ask further questions in order to use the inhaler correctly. Moreover, in a subanalysis of ease-of-use and inhaler competence data in patients with asthma,14 95% of patients used the ELLIPTA DPI correctly after the initial demonstration of correct usage at randomization; the most common error (2% of patients) was opening the cover incorrectly. A further 4% of patients were able to use the inhaler correctly at randomization after one additional instruction.14 In our study, the time of handling instruction needed was shorter for the ELLIPTA DPI compared with the BREEZHALER DPI in subjects who were not able to use the inhaler following nonverbal instruction. Finally, for the eight subjects in the BREEZHALER group who moved the BREEZHALER close to their mouth without removing the cap and the one subject in the ELLIPTA DPI group who moved the ELLIPTA DPI close to their mouth while holding it in a vertical orientation against the mouth, these events may have been influenced by the study design, which was to evaluate the subjects’ performance up to the time just before inhalation – study subjects did not place the mouthpiece in their mouths when handling the inhalers.

This study has strengths and limitations. A crossover study design was used to reduce bias resulting from potential variations between study groups, and to balance possible order and carryover effects. As study subjects were inhalation device-naïve, ease of handling could be assessed irrespective of pharmacological efficacy and without the influence of prior experience or knowledge of inhalers confounding the results. The population demographics enable the study findings to be extrapolated to patients with COPD and to elderly patients with asthma; however, it is also important to consider that the study subjects did not have a long history of DPI use.

The results reported here do not reflect all the factors that may influence inhaler preference in a real-world setting in patients with respiratory disease, where treatment efficacy, number of inhaler(s)/daily inhalation(s), or other patient-specific factors may also be important. For example, BREEZHALER users are able to determine if they have inhaled the medication correctly by listening for a whirring sound when breathing in and subsequently checking the empty capsule; this property is specific to this inhaler and may influence patient assessment of ease of use and ease of determining the number of doses remaining. Subjects responded to the questionnaire without having used the inhaler repeatedly as a patient would in clinical practice; therefore, it was not within the scope of the study to identify recurrent usage errors and drivers of patient preference in everyday use. In a real-world setting, patient and clinician evaluations of some aspects of inhaler use may, therefore, vary from the findings presented here.

Thus, further investigations in real-life settings will be important for a more thorough understanding of all the factors affecting inhaler preference. Such data may also be useful for assessing whether errors in using an inhaler can affect clinical outcomes. In this study, the inhalers did not contain any active drug and therefore no clinical effectiveness or safety data could be gathered.

In conclusion, among inhalation device-naïve Japanese volunteers aged ≥40 years, the ELLIPTA DPI is simple to use and is preferred to the BREEZHALER DPI for several reasons, including ease of use. The proportion of subjects who made handling errors when using the inhaler without prior verbal instruction was lower with the ELLIPTA DPI than with the BREEZHALER DPI. Although further real-world studies are needed, these findings in people without previous inhaler experience suggest that the ELLIPTA DPI is associated with fewer handling errors and is preferred for its ease of use.

Author contributions

YK, AK, and RS participated in the conception and design of the study, and in analysis and interpretation of the data. AA participated in the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors revised the manuscript and read and approved the final version.

Disclosure

YK provided paid consultancy services to GSK for administration of this study and has received financial reimbursement from GSK for providing lecture services. AA, AK, and RS are employed by GSK, and RS also owns stocks in GSK. This study was funded by GSK (study number 200372). Editorial support in the form of development of the draft outline in consultation with the authors, development of the first draft of the manuscript in consultation with the authors, editorial suggestions to draft versions of this paper, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, copyediting, fact checking, referencing, and graphic services were provided by David Cutler at Gardiner-Caldwell Communications (Macclesfield, UK) and was funded by GSK.

References

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD – updated January 2014. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org. Accessed July 30, 2014. | |

Lavorini F, Magnan A, Dubus JC, et al. Effect of incorrect use of dry powder inhalers on management of patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med. 2008;102:593–604. | |

Raherison C, Girodet PO. Epidemiology of COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2009;18:213–221. | |

Vincken W, Dekhuijzen R, Barnes P; ADMIT group. The ADMIT series – issues in inhalation therapy. 4) How to choose inhaler devices for the treatment of COPD. Prim Care Respir J. 2010;19:10–20. | |

Jarvis S, Ind PW, Shiner RJ. Inhaled therapy in elderly COPD patients; time for re-evaluation? Age Ageing. 2007;36:213–218. | |

Giraud V, Roche N. Misuse of corticosteroid metered-dose inhaler is associated with decreased asthma stability. Eur Respir J. 2002;19: 246–251. | |

Chrystyn H, Small M, Milligan G, Higgins V, Gil EG, Estruch J. Impact of patients’ satisfaction with their inhalers on treatment compliance and health status in COPD. Respir Med. 2014;108:358–365. | |

Shikiar R, Rentz AM. Satisfaction with medication: an overview of conceptual, methodologic, and regulatory issues. Value Health. 2004;7: 204–215. | |

Komase Y, Akimoto A, Kobayashi A. [Evaluation of operability of a novel inhaler – A study of handling errors in inhalation therapy-naive subjects]. Allergy Meneki. 2014;21:146–160. Japanese. | |

Breezhaler patient information leaflet. Available from: http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/23261/PIL/Onbrez+Breezhaler+150+and+300+microgram+inhalation+powder,+hard+capsules. Accessed September 17, 2014. | |

Chapman KR, Fogarty CM, Peckitt C, et al. Delivery characteristics and patients’ handling of two single-dose dry-powder inhalers used in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:353–363. | |

Nimmo CJ, Chen DN, Martinusen SM, Ustad TL, Ostrow DN. Assessment of patient acceptance and inhalation technique of a pressurized aerosol inhaler and two breath-actuated devices. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:922–927. | |

Svedsater H, Dale P, Garrill K, Walker R, Woepse MW. Qualitative assessment of attributes and ease of use of the Ellipta™ dry powder inhaler for delivery of maintenance therapy for asthma and COPD. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:72. | |

Svedsater H, Jacques L, Goldfrad C, Bleecker ER. Ease of use of the Ellipta dry powder inhaler: data from three randomised controlled trials in patients with asthma. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14019. |

Supplementary materials

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.