Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 13

Determinants of Frequency and Contents of Postnatal Care Among Women in Ezha District, Southern Ethiopia, 2020: Based on WHO Recommendation

Received 16 November 2020

Accepted for publication 4 February 2021

Published 16 February 2021 Volume 2021:13 Pages 189—203

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S291731

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Professor Elie Al-Chaer

Aklilu Habte,1 Samuel Dessu2

1Department of Reproductive Health, School of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wachemo University, Hosanna, Southern Ethiopia; 2Department of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wolkite University, Wolkite, Southern Ethiopia

Correspondence: Aklilu Habte Hailegebireal Tel +251912744786

Email [email protected]

Background: Postnatal care is a constellation of preventive care, practices, and assessments intended to detect and treat complications for both the mother and the newborn in the first six following birth. Monitoring of the content and frequency of the PNC is required to make the service provision more successful. However, several studies centered on the general PNC visits, and pieces of evidence were limited at the country level on the core content of the PNC, including the current study area. Therefore, this study aimed to identify determinants of the frequency and content of PNC visits among women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Ezha district, Southern Ethiopia.

Methods and Materials: A community-based cross-sectional survey was conducted in the Ezha district to collect data from 568 respondents by using pre-tested, interviewer-administered questionnaires. Data were entered into EpiData3.1 and exported to SPSS version 23 for analysis. To determine the wealth status of the respondents, the Principal Component Analysis was undertaken. To evaluate the determinants of frequency and the content of PNC, both binary logistic regression and generalized linear regression with Poisson type were applied respectively.

Results: Nearly a quarter (23.9%) of respondents received three or more postnatal visits, and only 81 (14.6%) respondents received all the PNC service contents suggested by WHO. Identified predictors of the core content of PNC were, frequencies of ANC (AOR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.15– 1.35), enrollment in community-based health insurance scheme (AOR: 0.69 (95% CI: 0.64– 0.75), and PNC frequency (AOR: 0.64, (95% CI (0.57– 0.73).

Conclusion: A low level of WHO-recommended frequency and content of the PNC were identified in the study area. To achieve better utilization, strengthening efforts to improve adequate ANC uptake, enrollment in the CBHI scheme, and working on a model household creation were, therefore, should be crucial measures.

Keywords: postnatal care, contents of postnatal care, determinants

Background

Despite several global and national initiatives aimed at improving maternal and newborn health, death continues to be a global challenge.1 In the low and middle-income countries (LMICs), the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) was approximately 20 times higher compared to mortality in high-income countries.2 In 2015, around 303,000 maternal deaths occurred worldwide, and more than 65% of maternal deaths occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in Ethiopia is 353 out of 100,000 live births, with a neonatal mortality ratio of 29 out of 1000 live births.3 Ethiopia was sorted among five countries signifying 50% of global neonatal deaths, such as India, Pakistan, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, according to the 2017 UNICEF report.4 Although there are several reasons, most of those deaths were occurred at birth or during the postnatal period due to insufficient visits and contents care.5,6

Postnatal care (PNC) services are described by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a constellation of preventive care, practices, and assessments aimed at recognizing and handling complications for both the mother and the newborn in the period between the expulsion of the placenta and the first six weeks of childbirth.7 The WHO recommended a minimum of three PNC visits with nine basic contents of care to mothers and babies to improve their survival by recognizing the role of appropriate PNC uptake during this critical period. The recommended postnatal visits are: within the first 24 hours, 3–4days, 7–14 days, and 6 weeks of delivery.7,8

To make it successful, monitoring of the content of PNC is needed, which include, assessment of newborns for key clinical danger signs and referral as required, promotion of early and exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), mother’s assessment, supplementation of iron and folic acid (IFAS), advice on reproductive health issues, provision of prophylactic antibiotics, provision of psychosocial support, addressing key messages among families and mothers regarding newborn care, and use of chlorhexidine for baby’s umbilical cord care.7,9

Receiving the recommended visits and core contents care promotes and maintains the well-being of mothers and newborns through the identification and management of complications caused by pregnancy and childbirth.7,9,10 Therefore, within the first 42 days of postpartum, all women should ideally have at least three contacts from skilled healthcare providers.7,11 PNC should be provided with multiple visits, rather than a single encounter, to optimize the health of women and infants, by addressing acute postpartum problems.12 Pieces of evidence have shown that achieving these recommended visit regimes and contents of care by skilled health care providers at a 90% coverage level could prevent up to 310,000 newborn deaths per year in Africa.5,13

Although the use of PNC has all increased in the last 20 years, there are enormous inequalities in timing, frequency, and comprehensiveness of care.14,15 Just about 41% of Sub-Saharan African mothers visit the PNC within 48 hours of childbirth and too few of them have complied with recommended frequency and contents of care.16 Although improvements in the accessibility of most maternal and child health services have been made, reports have shown that the national prevalence of the use of PNC services in Ethiopia is still low, with 17% coverage.17 Studies conducted in countries such as Myanmar, India, Ghana, Tanzania, and Ethiopia have shown that the use of WHO-recommended PNC visits is between 10% and 60%.18–22 Insufficient uptake of PNC visits and contents of care could result in significant ill health for both mother and newborn.4,9

The provision of adequate PNC visits and contents of care to postpartum women is one of the key strategies of the Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality (EDPMM) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) as a strategy to achieve the global target of reducing maternal mortality (70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births).23,24 In recent years, many high-impact interventions have been implemented by the Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia to improve maternal and child health services and adequate PNC provision is among those interventions with a 95% coverage plan by 2020.25

Existing studies have focused on the general PNC assessment of at least one visit26–31 and little has been done on the WHO-recommended minimum of three visits.18,20–22 Besides, the average and range of visits and content of care by skilled health care providers during postpartum visits (PPVs) were not well addressed. Although this research was limited to a district in southern Ethiopia, it considered women who did not receive WHO’s recommended PNC visits and contents of care which might make the study the first in type at the national level. To assist in the development and implementation of evidence-based approaches to service improvement, a clear understanding of the factors associated with the frequency and content of PNC services is important. The study, therefore, aimed to identify determinants of the use of WHO-recommended PNC visits and contents of care among rural women of Ezha district, Southern Ethiopia, 2020. The findings of this study could help to improve maternal and Child health program planning and policymaking.

Methods and Materials

Study Setting, Design, and Period

In the Ezha District, located 198 km South of Addis Ababa (the capital city of Ethiopia), a community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from march 1–30, 2020. The district has 28 rural Kebeles (Kebele: the smallest administrative unit in the current Ethiopian government structure under the district). The total population of the district in 2019 was 112,948, based on the 2007 CSA estimate. The primary health care units offering maternal and child health services in the district were four health centers, one non-profitable NGO clinic, and 28 health posts (one in each kebele).

Populations of the Study

The source populations were all women in Ezha district who gave birth in the last 12 months. The study populations were women from the selected Kebeles of the district who stayed six or more weeks after delivery. The research excluded mothers who have been living in the study area for less than 6 months, who have given birth at home, and who have been critically ill during the time of data collection.

Sample Size Determination

Initially, the sample size for this study was determined using the stat calc menu of Epi-info software version 7 using the single population proportion parameters with an estimated PNC prevalence of 28.4% obtained from a study conducted in Northern Ethiopia,22 95% confidence level, 5% degree of precision.

After using the 1.5 design effect and 10% non-response rate, the sample size for the first objective was 515.

Then, with consideration of factors affecting PNC frequency, assumptions for a two-population proportion were made. The largest sample size (n=568) was obtained among those factors chosen by considering: percent of PNC among women who did not attend secondary education (16.06%), AOR of 2.16,18 80% power, 95% confidence level, the ratio of unexposed to exposed equally to 1, 10% non-response rate, and design effect pf 1.5. Finally, the sample size obtained using two population proportion considerations (n=568) was larger than the sample size for a single population proportion (n=515) and it was taken as the final sample size for the study.

Sampling Techniques

To get study participants, a two-stage sampling technique was used. The district consists of 28 Kebeles, and ten Kebeles were randomly chosen by the lottery method. The list of women who gave birth in the last 12 months and stayed six or more weeks after delivery was obtained from each Kebele’s health post record. Eligible women in each selected Kebele were enumerated and reassured with the aid of health extension workers. For those houses with eligible study participants, codes/numbers were then given and a sampling frame was created. The sample size was determined by proportional allocation for each Kebele. Finally, by using a computer-generated random number, study participants were selected and interviewed at the household level. If more than one eligible woman were living in the same home, only one study participant was chosen by the lottery method. When the chosen households were closed during data collection, the interviewers revisited the households at least three times at various time intervals. The interviewer moves on to the next household assigned by the field supervisor if participants could not be accessed within three visits.

Data Collection Tools, Methods, and Personnel

Six trained diploma nurses with expertise in data collection have collected the data through face-to-face interviews with the supervision of two public health officers working in the district. By reviewing relevant literature with appropriate adjustments, a pre-tested standardized questionnaire was created.7,20–22 Structured questionnaires were used to collect information about respondents’ socio-economic and demographic, obstetric, knowledge, and health care system-related characteristics. The socio-economic status of households was assessed using an adapted tool from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2016 Report.17 Supervisors and data collectors used guidance to access selected women’s homes from the local Health Development Army and community volunteers in each Kebele. Finally, at their residential home, study participants were interviewed.

Data Quality Management

Initially, the questionnaire used to collect data was prepared in English and translated by an expert in that language into the local language and eventually back-translated to English to verify its continuity with the original meanings. Both data collectors and supervisors were given intensive training, lasting one day, on data collection methods and instruments. One week before the actual data collection, a pre-test was performed for 5% of the sample size (29 women) in the Cheha district. All the necessary corrections were made based on the pre-test result. A day-to-day follow-up was carried out by the principal investigator and supervisor over the entire data collection period. Every day, after data collection, each questionnaire was reviewed and checked by the supervisors and the principal investigator for completeness, supplemented with feedback. To minimize social desirability bias, study participants were interviewed privately.

Data Analysis

Using Epi-data software version 3.1, the data was entered and coded and then exported to the SPSS version23 for further analysis. To measure variables, descriptive statistics such as frequency distributions, mean and standard deviation have been computed. By using principal component analysis (PCA), the wealth status of the individual household was analyzed. Initially, 28 products were used. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin’s sampling adequacy measure (≥0.6), Bartlett’s Sphericity test (p-value < 0.05), and anti-image correlations (> 0.4) were tested for sampling adequacy of individual variables to comply with PCA assumptions.

A binary logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with the primary outcome variable (frequency of WHO-recommended PNC visit). The Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit tests and Nagelkerke R Square were used to test model fitness and were 0.64 and 0.548 respectively. Multicollinearity between the explanatory variables was checked using the variance inflation factor (VIF>10). Variables having a p-value of < 0.25 in bivariable logistic regression were chosen as candidates for multivariable logistic regression analysis. To report the association between the outcome and explanatory variables, the adjusted odds ratio and its 95% confidence interval were used, and the statistical significance of each variable was declared at a p-value < 0.05 in the multivariable logistic regression model.

ANOVA and independent t-tests were used to verify statistical significance between explanatory variables and the content of the PNC received, which was the secondary outcome variable in this study. To classify the determinants of the PNC content, multivariate statistical analysis using the Generalized Linear Models (GLM) approach was carried out. Since the contents of the PNC were count variables, Poisson regression was used. The assumption of equal dispersion is fulfilled when the assumption for the Poisson regression model is checked. Finally, to report the statistical significance of the independent variables, the odds ratios and their 95% confidence CI were used.

Measurement of Variables

Outcome Variables

Primary outcome variable: Postnatal care frequency is a dichotomous variable that was assessed as to whether or not mothers had three or more of the four recommended PNC visits by the WHO. These visit schedules are: within 24 hours, on 3–6 days, within 7–14 days and subsequently at 6th week via a home or facility-level visits by skilled health care providers.7,18,22

Secondary outcome variable: The contents of PNC services which are nine. These are an assessment of newborns for key clinical danger signs and referral as necessary, promotion of early and exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), assessment of maternal health for danger signs, iron and folic acid supplementation (IFAS), counseling on reproductive health issues, provision of prophylactic antibiotics, provision of psychosocial support, addressing key messages to mothers and families on newborn treatment and the use of chlorhexidine for the umbilical cord of the baby.7,9 The response categories were defined as “YES=1” and “NO=0” for each service item. A composite index was created, with a minimum and maximum of 0 and 9 scores, respectively. She did not use any services if the mother scored zero and if she scored nine, she used all services during PNC visits.7,18

Explanatory Variables

Skilled health care providers: Health care professionals working in health facilities, such as doctors, nurses, midwives, health officers, or health extension workers, who have the necessary competencies to provide postnatal care service.17

Knowledge about PNC: This is the familiarity or awareness of respondents of having PNC information, post-natal care content, PNC advantages, and consequences of not receiving PNC, frequency, and timing of PNC, maternal and newborn danger signs during PPP. A composite index has been developed that summarizes the level of knowledge. Finally, it was deemed that a respondent who scored at least the mean value (4.47) was knowledgeable; if not, she was categorized as not knowledgeable.

Being a model household (MHH): Those respondents who implemented all health extension packages and received certificates of recognition and appreciation from the concerned bodies.32

Autonomy to maternity care: These are ways of deciding and managing resources when women can access maternal health care services and are classified as autonomous if she chose to seek maternal and child health care alone or with her husband (jointly); otherwise non-autonomous, meaning a husband alone or a third party decided to use the service.17

Accessible distance to nearby health facility: if a mother travels for no more than one hour on foot or by local means to reach health facilities.33

Community-based health insurance (CBHI) scheme enrollment status: Acceptance to be a member of the system and paid a fee for a full year and have an updated service card.34

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. The maternal age was ranged from 18–42 with an average of 28.8 ± 5.3 years. The majority (93.5%) of respondents were married. More than two-fifth (41.7%) of study respondents did not have formal education. Almost half (49.5%) of them were orthodox by religion and Gurage was the predominant ethnic group (93.2%)

|

Table 1 Sociodemographic Characteristics of Respondents in Ezha District, Southern Ethiopia, March 1–30, 2020 |

Obstetric Characteristics of Respondents

Table 2 shows the obstetric characteristics of respondents. Almost half (50.4%) of the respondents in the study were multi-parous. Around nine out of ten mothers (89.2%) received at least one ANC visit during their last pregnancy, and 124 (22.3%) of them received four or more visits. Regarding the place of ANC visit, 414 (83.5%), 61 (12.3%), and 21 (4.2%) got the service at the health center, Hospital, and Health post respectively. Concerning the place of delivery, more than three-quarters (75.7%) of respondents gave their last birth in health centers. Forty-one (7.4%) of mothers delivered their last child by Caesarean section.

|

Table 2 Obstetric Characteristics of Respondents in Ezha District, Southern Ethiopia, March 1–30, 2020 |

Maternal and Neonatal Health Conditions During Pregnancy and Post-Partum Period

The last pregnancy was complicated in more than a quarter (n=147, 26.8%) of respondents with at least one danger sign reported. The major complaints mentioned by them were persistent vomiting 58 (38.9%) and a gush of fluid before the onset of labor 31 (20.8%) (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Danger signs reported by respondents during their last pregnancy in Ezha district, Southern Ethiopia, March 1–30, 2020 (n=149). |

Of the total respondents, 132 (23.7%) testified that they experienced at least one maternal health problem during the post-partum period. Breast conditions (31.8%), abnormal vaginal bleeding (34.4%), high-grade fever (26.2%), severe abdominal pain (7.7%), and swelling of extremities (2.5%) were the main health problems pointed out by the respondents. On the other hand, 141 (25.0%) of respondents stated that they have already faced at least one newborn illness during the postpartum period. Major newborn complaints were unable to of breastfeeding (53.1%) and breathing difficulty (30.4%), followed by umbilical area infections (11.7%), vomiting (9.4%), and high-grade fever (8.6%).

Level of Knowledge of Respondents on PNC Service

A composite knowledge indicator was built, whereby 136 (24.5%) of women had good knowledge about PNC service. About information exposure, 355 (63.8%) of respondents heard about PNC service. Nearly three quarters (74.9%) and 156 (43.9%) obtained information from health extension workers and other health care providers, respectively. Nearly half (49.2%) of mothers knew at least one advantage of receiving PNC. Around a quarter (23.3%) of respondents knew the time for PNC service delivery (ie following delivery and lasts till six weeks) whereas only 102 (18.4%) knew the recommended frequency of postnatal visits (ie at least three visits). Furthermore, 54.9% and 57.4% of mothers knew at least one maternal and newborn danger signs during postpartum periods respectively. Almost two-fifths (39.7%) of respondents can mention at least one type of care provided during PNC visits.

Health System-Related Characteristics of Respondents

The average time on foot to access the nearest health facility was 52.41 minutes with a range of 10–120 minutes, and 361 (64.9%) of respondents accessed the health facility within an hour. The majority (87.4%) of respondents were autonomous concerning autonomy for the use of maternal health services. For their completion of health extension packages, almost half (48.4%) of respondents were accredited as a model household (MHH). Of the study participants, more than six out of ten (63.1%) were enrolled in the community-based health insurance (CBHI) scheme.

Frequency of WHO-Recommended Postnatal Care (PNC) Service

From a total of 556 respondents, 109[23.9%; 95% CI: (19.9, 27.5)] received at least three postnatal visits by skilled health care providers. Regarding the timing of PNC visits, 392 (70.5%) mothers received their postnatal contact within the first 24 hours of delivery. Also, 296 (53.2%) and 248 (44.1%) respondents received a postnatal visit on 3–6th days and 7–14 days respectively. Relatively few mothers (27.3%) got the service in the sixth week. Regarding the service delivery platform, nearly three-quarters (74.9%) of respondents got the service by health extension workers through a home-to-home visit and/or at the health post level while the remaining (25.1%) got the service at the health center and hospital level. The main reason mentioned by respondents for not complying with the recommended PNC visit schedules would have been to feel safe during that period (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 Reasons for non-compliance with the prescribed PNC visit schedules among respondents in Ezha District, Southern Ethiopia, March 1–30, 2020 (n=447). |

Determinants of the Frequency of PNC Service

In bivariate analysis, twelve variables showed a significant association and were eligible for multivariable logistic regression. Maternal education, frequency of antenatal care, mother’s knowledge of PNC, having enrolled in community-based health insurance (CBHI) scheme, and being a model household were found to be significantly associated with PNC frequency in the multivariable logistic regression analysis.

In comparison to mothers lacking formal education, the odds of receiving at least three PNC visits were 4.3 times higher for those pursuing a college education and above (AOR: 4.34, 95% CI: 2.25–9.21]. Similarly, for mothers who have received four or more ANC visits, the odds of receiving at least three PNC visits are 4.2 times higher than for those who have received at most one (AOR: 4.23, 95% CI: 1.93–8.85). Being a model household was significantly associated with receiving adequate PNC visits. Compared to their counterparts, the chances of receiving adequate PNC (three or more visits) among mothers from the model household were 3.3 times greater (AOR: 3.33, 95% CI: 1.75–6.35). In contrast to those with poor knowledge, women with good knowledge of postnatal care also had a higher chance of complying with PNC visit schedules (AOR: 3.18, 95% CI: 1.72, 5.87). Those mothers who were enrolled in the CBHI scheme were 4.8 times more likely to experience PNC visit schedules recommended by the WHO (AOR: 4.81, 95% CI: 2.38, 8.73) (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Determinants of Frequency of Postnatal Care of Women in Ezha District, Southern Ethiopia, March 1–30, 2020 |

Contents of Postnatal Care

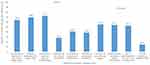

In the current study, the mean PNC content uptake score was 4.91, with an SD of 2.2. All the nine selected elements of PNC services were received by only 81 (14.6%) of mothers. Promoting early and exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) was the most common item taken by 402 (72.3%) of mothers among the core elements of PNC, closely followed by an assessment of maternal danger signs by 69.6% of mothers (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3 Percentages of respondents getting each WHO-recommended contents of care during PNC visit in Ezha district, Southern Ethiopia, March 1–30, 2020 (n=556). |

Determinants of Contents of Antenatal Care

Using a generalized linear model (GLM) with Poisson type, the analysis of this study found that three variables, namely the frequency of postnatal care, the receipt of four or more ANC visits, and enrolment in community-based health insurance (CBHI) scheme, were a significant predictor of receiving contents of PNC.

Mothers who had less than three PNC visit schedules were 36% less likely to receive items of PNC content (AOR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.57–0.732). It has also been established that being a member of the CBHI scheme is an essential determinant of the usage of the contents of PNC. Those mothers who were not a part of the CBHI scheme were 31% less likely to receive PNC content (AOR: 0.69, CI 95%: 0.64–0.75). The likelihood of adoption of the core contents of PNC was higher among mothers who received all the recommended ANC visits. In contrast to mothers with at most one visit, those mothers who had four and more ANC visits were 1.25 times more likely to get core contents of PNC (AOR: 1.25, 95% CI:1.15–1.35) (Table 4).

Discussion

It is recognized that maternal and newborn complications can be minimized by the timely and quality delivery of maternal and newborn interventions at high coverage. However, the contents of postnatal care given to the mother and newborn in the study area by skilled health care providers, in general, was 14.6% (95% CI: 11.7–17.6) with a mean score of 4.91 and is lower compared to a previous study conducted in Uganda.35 This could be due to little attention given by HEWs and government officials to core elements of postnatal services; as illustrated by our finding and concerted effort is required in advance.

Compared to studies conducted in rural Myanmar and China, most of the figures from the research were higher for each item of care during visits.18,36 A study conducted in Myanmar indicated that information on exclusive breastfeeding and postnatal danger signs was provided to 48.1% and 51.6% of mothers, respectively.18 Both figures were 72.3% and 69.6% correspondingly in the current study. Similarly, in China, where 37%, 32%, and 18% of respondents received EBF promotion, cord care, and education on danger signs, which are lower than the current study, respectively.36 These discrepancies in contents of care may be attributable to differences in the utilization of maternal health care (ANC, skilled delivery, and early PNC), in which the uptake of such services in the current study area was higher. In contrast, the Myanmar study reported that postnatal iron supplements were given to almost all mothers (98.8%). This could be due to changes in health policy, in which the country promotes IFAS as a compulsory PNC service.18

As a factor that affects the use of PNC content, the number of postnatal visits is identified. This is clarified as the higher number of visits to the PNC will improve the likelihood of PNC items. A study carried out elsewhere supports this.18 So that this finding implies that local managers and policymakers should strengthen the implementation of WHO-recommended postnatal visit schedules. Besides, there should be awareness creation sessions to help mothers appreciate the effects of frequent visits, as recommended by a health professional.

This study finds low levels (23.9%) of WHO’s recommended minimum PNC visits by mothers. Maternal education, frequency of antenatal care, awareness of mothers on PNC, and being a model household have been identified as important determinants of frequency of PNC. The minimum recommended PNC frequency in the area was lower than documented in studies conducted in India, rural Ghana (districts of Builsa and Mamprusi), and northern Ethiopia.19,20,22 This suggests the frequency of PNC in the study area is not satisfactorily consistent with WHO guidelines on optimal PNC visits.7 On the other hand, compared to the study of a survey conducted in three rural districts of Tanzania in which only 10.4% of mothers complied with the minimum PNC visits recommended by the WHO, the result in the current study was higher.21 The disparity may be due to the difference in time gap, as access to healthcare and understanding of the program might improve over time.

In this study, as compared to those women without formal education, the likelihoods of receiving adequate PNC visits were higher among women attending college education and above. This result was supplemented by studies that have been conducted elsewhere.18,19,21,22 This could be explained by the notion that education is one of the key factors that improve maternal autonomy which in turn improves maternal and child health services seeking behavior.37 In conjunction, mothers with higher education levels may be able to be exposed to different sources of information with satisfactory information processing skills, which may lead mothers to comply with the recommended visits.

According to this study, women’s knowledge of postnatal care was one of the factors that boosted the odds of receiving adequate PNC visits. This is supported by studies undertaken elsewhere.18,19,31 This is plausible because the more adequate postnatal care knowledge a mother has (such as its benefits, care content, the timing of the visit, the consequence of not receiving the service, and danger signs in the postpartum period), the more she complies with the prescribed PNC visits.27,28,38 Therefore, there is a need for concerted efforts by the concerned bodies to enhance women’s awareness of the PNC so that women and newborns can benefit from service adoption.

In the current study, the likelihood of receiving adequate PNC was greater among women who were from the model household (MHH) than their counterparts. This finding is supported by the study conducted in Ethiopia.32 This may be because Health Extension Workers (HEWs) invest more time on capacity building for model HHs through intensive training, support, and follow-up with practical demonstration and family education on maternal and child health services for those chosen to be role models.25,39,40 Such practices may lead to the development of skills to make recommended postnatal visits too well practiced compared to their counterparts. Findings from previous studies have shown that mothers from MHHs have good use of maternal health services.32,41,42 These explanations might be well supported by the evidence from the current study in which 83.5% of mothers who got WHO-recommended PNC visits were from MHHs.

One of the variables positively associated with both the frequency and content of PNC is the frequency of antenatal care. This result was in tandem with a previous study in Ghana.20 The potential reason for this finding could be that adequate antenatal care allows women the opportunity to be advised on the value, availability, scheduling, and content of the recommended PNC service scheme, which might contribute to the uptake of adequate PNC visits and content of care. We strongly suggest, thus, that the provision of appropriate ANC is an essential input for improving the PNC’s accessibility and quality. On the other hand, the finding is inconsistent with findings from Myanmar, Tanzania, and northern Ethiopia.18,21,22 This may be attributed to the variation in the proportion of women attending adequate ANC, in which the majority of 70.6% of adequate PNC uptake was experienced by those mothers with three or more prenatal visits.

The enrollment status of mothers in the community-based health insurance (CBHI) scheme was another predictor that demonstrates a significant association with both frequency and contents of PNC. While a lack of information on the association of this variable with PNC frequency and content was found, some pieces of evidence showed that if the mother is a member of CBHII, the maternal postnatal visit is more likely.43 This may be, once they were enrolled in the program, all costs were covered and, as a result, the demand for maternal health services might be increased. As there is no fear/concern for payment, their contact and engagement with the community health workers and health facilities have been improved. These possible justifications have been supported by numerous studies elsewhere.44–46 Therefore, the local administrative authorities should make efforts to enroll mothers in the CBHI scheme.

There were both strengths and shortcomings of this study. There was insufficient evidence based on the latest WHO guideline (2013) on the determinants of both the frequency and the content of PNC.7 Thus, it could be used at the local and policy level as an input. Since this study is cross-sectional, there was no relationship between cause and effect reported. Although more recent births were considered, due to the recall bias, it may be difficult to remember the exact content and visits given by skilled health care providers during the postnatal period. Finally, the study was based on self-reports and this might have resulted in social desirability bias.

Conclusion

A low level of WHO-recommended frequency and core content of the PNC were identified in the study findings. This result suggests that not only does the government concentrate on the frequency of PNC visits, but also pay attention to the content of care to boost the quality of the service. In this study Frequency of ANC and enrollment in the CBHI scheme were identified as a determinant for both frequencies of the ANC and the contents of ANC care. To achieve better utilization, strengthening efforts to improve adequate ANC uptake, enrollment in the CBHI scheme, and working on a model household creation were, therefore, should be crucial measures. As this analysis is cross-sectional, as the frequency of PNC certainly affects the content of the PNC, it is hard to bring it to a close. For that reason, these results could be supported by further study with analytic and experimental design.

Abbreviations

ANC, antenatal care; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CBHI, community-based health insurance; HEWs, health extension workers; MMR, maternal mortality ratio; PCA, principal component analysis; PNC, postnatal care; SDG, sustainable development goal; SPSS, statistical product and service solutions; WHO, world health organization.

Data Sharing Statement

The data used to strengthen the results of this study are to be had from the corresponding author based on reasonable request via the email address of [email protected].

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was approved and conducted per the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board/IRB of Welkite University, College of Medicine and Health Science, School of Public Health. Respondents have been told of the study’s intent and procedure. For those aged 18 and over, written informed consent was obtained from study participants. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardian using normal disclosure procedures for those participants aged less than 18 years. A specific ID number was issued to preserve the questionnaire’s anonymity. Privacy and confidentiality of participants were guaranteed before data collection. Also, respondents were well aware that the data they provided during the study would be used solely for study and would not be revealed to anyone outside the research team. A formal letter of permission was obtained from Ezha district health office.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Wolkite University College of medicine and health science, department of public health for giving Ethical clearance to undertake the study. Our appreciation also goes to the managers and healthcare providers who worked in the Ezha district Health Office for their assistance and cooperation during the study. Finally, for their efforts, we want to thank our supervisors, data collectors, and study participants.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. WHO. Global Strategies for Women, Children, and Adolescents (2016–2030). 2016.

2. Stenberg K, Sheehan AH, Sheehan P, et al. Advancing social and economic development by investing in women’s and children’s health: a new global investment framework. Lancet. 2014;383(9925):1333–1354. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62231-X

3. UNICEF. Maternal and newborn health disparities in Ethiopia, UNICEF for every child; 2017. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/country_profiles/Ethiopia/country%20profile_ETH.pdf.

4. UNICEF, W. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality, Estimates Developed by the UN Interagency Group for Child Mortality Estimation United Nations Report. 2017.

5. Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, et al. Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet. 2005;365(9463):977–988. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71088-6

6. WHO, UNICEF. Home Visits for the Newborn Child: A Strategy to Improve Survival. 2010.

7. WHO. Recommendations on Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn. World Health Organization; 2014.

8. Organization, W.H. WHO Recommendations on Newborn Health: Guidelines Approved by the WHO Guidelines Review Committee. World Health Organization; 2017.

9. WHO. Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A Guide for Essential Practice.

10. Organization, W.H. WHO Technical Consultation on Postpartum and Postnatal Care. World Health Organization; 2010.

11. ACOG. American college of obstetricians and gynecologists, optimizing pnc, the presidential task force on redefining the postpartum visits committee on obstetric practice; 2018. Available from: https://www.Acog.Org/-/media/committee-opinions/committee-on-obstetric-practice/co736.Pdf?Dmc=1&ts=20180522t1442482827.

12. Organization, W.H. Health in 2015: From MDGs, Millennium Development Goals to SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. 2015.

13. Aboubaker S, Qazi S, Wolfheim C, et al. Community health workers: a crucial role in newborn health care and survival. J Glob Health. 2014;4(2). doi:10.7189/jogh.04.020302.

14. Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(6):e323–e333. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X

15. WHO, U., UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Population Division. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF. Geneva: UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Population Division; 2015.

16. Organization, W.H. World Health Statistics 2014: A Wealth of Information on Global Public Health. World Health Statistics 2014: A Wealth of Information on Global Public Health. 2014.

17. Central statistics agency of Ethiopia, Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey(EDHS) 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF; 2016. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR328/FR328.pdf.

18. Mon AS, Wilaiphorn Thinkhamrop MKP, Thinkhamrop B. Utilization of full postnatal care services among rural Myanmar women and its determinants: a cross-sectional study. FlooResearch. 2018;7.

19. Paudel DP, Nilgar B, Bhandarkar M. Determinants of postnatal maternity care service utilization in rural Belgaum of Karnataka, India: a community-based cross-sectional study. Int J Med Public Health. 2014;4(1):96. doi:10.4103/2230-8598.127167

20. Sakeah E, Aborigo R, Sakeah JK, et al. The role of community-based health services in influencing postnatal care visits in the Builsa and the West Mamprusi districts in rural Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):295. doi:10.1186/s12884-018-1926-7

21. Kanté AM, Chung CE, Larsen AM, et al. Factors associated with compliance with the recommended frequency of postnatal care services in three rural districts of Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):341. doi:10.1186/s12884-015-0769-8

22. Akibu M, Tsegaye W, Megersa T, et al. Prevalence and determinants of complete postnatal care service utilization in Northern Shoa, Ethiopia. J Pregnancy. 2018;2018:2018. doi:10.1155/2018/8625437

23. UN-DESA. “Sustainable Development Goal 3: Ensure Healthy Lives And Promote Well-Being For All At All Ages,”,2017. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform; 2017.

24. Jolivet RR, Moran AC, O’Connor M, et al. Ending preventable maternal mortality: Phase II of a multi-step process to develop a monitoring framework, 2016–2030. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):258. doi:10.1186/s12884-018-1763-8

25. Health, E.F.M.O. Health Sector Transformation Plan (2015/16–2019/20). 2015.

26. Tesfaye TAAA. Postnatal care utilization and associated factors among women of reproductive age group in Halaba Kulito Town, Southern Ethiopia. Arch Public Health. 2018;76(9).

27. Angore BN, Tufa EG, Bisetegen FS. Determinants of postnatal care utilization in the urban community among women in Debre Birhan Town, Northern Shewa, Ethiopia. J Health Popul Nutr. 2018;37(10). doi:10.1186/s41043-018-0140-6

28. Belachew T, Taye A, Belachew T. Postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among mothers in Lemo Woreda, Ethiopia. J Womens Health Care. 2016;5(3):1–7. doi:10.4172/2167-0420.1000318

29. Fikirte Tesfahun WW, Mazengiya F, Kifle M, Kifle M. Knowledge, perception, and utilization of postnatal care of mothers in Gondar Zuria district, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(10):2341–2351. doi:10.1007/s10995-014-1474-3

30. Moreda TB, Gebisa K. Assessment of postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among mothers attending antenatal care at ambo health facilities. Epidemiol Int J. 2018;2(2).

31. Limenih MA, Endale ZM, Dachew BA. Postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among women who gave birth in the last 12 months prior to the study in Debre Markos Town, Northwestern Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Med. 2016;2016:7. doi:10.1155/2016/7095352

32. Darega B, Dida N, Tafese F, et al. Institutional delivery, and postnatal care services utilization in Abuna Gindeberet district, West Shewa, Oromiya Region, Central Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):149. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-0940-x

33. Heyi WD, Deshi MM, Erana MG. Determinants of postnatal care service utilization in Diga district, East Wollega zone, wester Ethiopia: case-control study. Ethiopian J Reprod Health. 2018;10(4).

34. Shibeshi S. Assessment of Factors Affecting Uptake of Community-Based Health Insurance Among Sabata Hawas Woreda Community, Oromiya Region. Addis Ababa University; 2017.

35. Namazzi G, Okuga M, Tetui M, et al. Working with community health workers to improve maternal and newborn health outcomes: implementation and scale-up lessons from eastern Uganda. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(sup4):1345495. doi:10.1080/16549716.2017.1345495

36. Chen L, Qiong W, van Velthoven MH, et al. Coverage, quality of and barriers to postnatal care in rural Hebei, China: a mixed-method study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):31. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-14-31

37. Sharma B, Shekhar C, Ranjan M, Chaurasia H. Effect of women’s empowerment on reproductive and child health services among south Asian women. Demogr India. 2017;46(2):95–112.

38. Workineh YG, Hailu DA. Factors affecting utilization of postnatal care service in Jabitena district, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2014;23(3):169–176. doi:10.11648/j.sjph.20140203.15

39. Wang H. Ethiopia Health Extension Program: An Institutionalized Community Approach for Universal Health Coverage. The World Bank; 2016.

40. Desta SH, Basha SY. The role of health extension workers in primary health care in AsgedeTsi’mbla District: a case of Lim’at T’abya health post. Int J Soc Sci Manag. 2017;4(4):248–266. doi:10.3126/ijssm.v4i4.18504

41. Karim AM, Admassu K, Schellenberg J, et al. Effect of Ethiopia’s health extension program on maternal and newborn health care practices in 101 rural districts: a dose-response study. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65160. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065160

42. Medhanyie A, Spigt M, Kifle Y, et al. The role of health extension workers in improving utilization of maternal health services in rural areas in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):352. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-352

43. DiBari JN, Yu SM, Chao SM, Lu MC. Use of postpartum care: predictors and barriers. J Pregnancy. 2014;2014:1–8. doi:10.1155/2014/530769

44. Tesfau YB, Kahsay AB, Gebrehiwot TG, et al. Postnatal home visits by health extension workers in rural areas of Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study design. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):305. doi:10.1186/s12884-020-03003-w

45. Comfort AB, Peterson LA, Hatt LE. Effect of health insurance on the use and provision of maternal health services and maternal and neonatal health outcomes: a systematic review. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31(4 Suppl 2):S81–S105.

46. Browne JL, Kayode GA, Arhinful D, et al. Health insurance determines antenatal, delivery, and postnatal care utilization: evidence from the Ghana demographic and health surveillance data. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e008175–e008175. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008175

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.