Back to Journals » Journal of Healthcare Leadership » Volume 13

Defence Healthcare Engagement: A UK Military Perspective to Improve Healthcare Leadership and Quality of Care Overseas

Authors Tallowin S, Naumann DN , Bowley DM

Received 20 January 2020

Accepted for publication 6 October 2020

Published 29 January 2021 Volume 2021:13 Pages 27—34

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S224906

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Russell Taichman

Simon Tallowin, David N Naumann, Douglas M Bowley

Academic Department of Military Surgery and Trauma, Royal Centre for Defence Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TH, UK

Correspondence: Douglas M Bowley

Royal Centre for Defence Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TH, UK

Tel +44 7810 308 167

Email [email protected]

Abstract: Defence Healthcare Engagement (DHE) describes the use of military medical capabilities to achieve health effects overseas through enduring partnerships. It forms a key part of a wider strategy of Defence Engagement that utilises defence assets and activities, short of combat operations, to achieve influence. UK Defence Medical Services have significant recent DHE experience from conflict and stabilisation operations (e.g. Iraq and Afghanistan), health crises (e.g. Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone), and as part of a long-term partnership with the Pakistan Armed Forces. Taking a historical perspective, this article describes the evolution of DHE from ad hoc rural health camps in the 1950s, to a modern integrated, multi-sector approach based on partnerships with local actors and close civil-military cooperation. It explores the evidence from recent UK experiences, highlighting the decisive contributions that military forces can make to healthcare leadership and quality of care overseas, particularly when conflict and health crisis outstrips the capacity of local healthcare providers to respond. Lessons identified include the need for long-term engagement with partners and the requirement for DHE activities to be closely coordinated with humanitarian agencies and local providers to prevent adverse effects on the local health economy and ensure a sustainable transition to civilian oversight.

Keywords: military medicine, conflict, humanitarianism, coaching

Introduction

Defence Engagement (DE) is the means by which the UK uses Defence assets and activities, short of combat operations, to achieve influence.1 It has been defined within Ministry of Defence doctrine as

An approach to relationship building through direct assistance and shared endeavour that creates the right conditions, spirit and capabilities to achieve a formal and enduring partnership.2

Relatively recently, a medical perspective to DE has been defined: Defence Healthcare Engagement (DHE) is the use of UK military medical capabilities to achieve Defence Engagement effects in the health sector, and since 2018, DHE has been considered a core task of the UK Defence Medical Services (DMS).3 The primary aim of DHE activities with overseas partners is to help improve healthcare leadership and quality of care. Healthcare is a universal need and therefore sincere efforts to help improve quality of healthcare are a non-contentious point of contact between UK assets and partner nations. In this way, healthcare can contribute to the wider aims of identification of early signs of instability and crisis, mitigation against their effects, and contribution to the efforts to (re-)establish security and stability.

Here we will explore how the concept of DHE has evolved from the counterinsurgency campaigns in South East Asia in the 1950s and 60s, through the conflict and stabilisation operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, and towards the more modern Humanitarian Assistance Operations such as the response to the West African Ebola epidemic.

DHE During Conflict and Stabilisation

Medical Civil Action Programmes

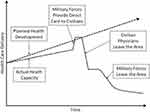

Over the past 50 years, DHE during conflict has evolved from isolated health camps providing direct healthcare for host nation populations to more structured coaching programmes working in partnership with local security forces and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). The former began as Medical Civil Action Programmes (MEDCAPs) during the counterinsurgency campaigns by the UK in Malaya (1948–60) and by the US in Vietnam (1955–75). These MEDCAP facilities provided temporary outpatient care to civilians in isolated rural areas with limited access to conventional healthcare. The perceived benefit of these camps from the command perspective was that they served a dual purpose—fulfilling obligations under international humanitarian law to ensure sufficient medical care was provided to the local population, whilst helping to win the battle for “hearts and minds” (a quote attributed to General (later Field Marshal) Sir Gerald Templer) and encouraging them to back the “legitimate” authorities.4 Whilst MEDCAPs had potential utility as a counterinsurgency strategy, there has been justification for concerns about quality of care and the impact on existing host nation health services. Although well-intentioned, interventions were often brief and rudimentary, with limited training provided to local providers.5 MEDCAPs have been described in the literature as a classic representation of “impatience and naivety”5 with potential to “undermine civilian confidence in their own providers, introduce competition, [and] skew the local healthcare market.”6 Figure 1 illustrates some of the unintended consequences of this style of military health development.

|

Figure 1 The unintended consequences of military health development. Reproduced from Wilson RL, Moawad FJ, Hartzell JD. Lessons for conducting health development at the tactical level. Mil Med. 2015;180(4):368–373, by permission of Oxford University Press.7 |

Provincial Reconstruction Teams

MEDCAPs continued to be used during the stabilisation campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan but were increasingly brought under the control of Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs). Developed by the US, and later extended into the UK’s area of operations in Basra (Iraq) and Helmand province (Afghanistan), PRTs were combined civilian-military organisations staffed by military officers, diplomats and subject-matter experts who coordinated the delivery of aid as “a means to extend the reach and enhance the legitimacy of the central government”.8 The structure and activities varied by lead-nation and administrative province. UK-led PRTs tended to have a greater proportion of civilian staff, and a more focussed security and governance agenda, with healthcare projects largely involving infrastructure development (e.g. establishing health clinics) rather than direct healthcare provision. The PRTs projects contributed to a numerical increase in healthcare facilities from 34 to 57 between 2006 and 2014, resulting in 80% of the Helmand civilian population being within 10km of a healthcare facility.9

In contrast, the US engaged more directly in the civilian health sector. In Ghazni province (Afghanistan) for example, the PRT held monthly meetings with the provincial health director and NGOs to identify priorities for public health. This led to bi-monthly village medical outreach operations (VMOP) to rural communities as a means of training to local healthcare providers, and the building of a new Emergency Room. In time, the public health directorate began to run its own VMOP and the number of local civilian trauma cases referred to the military field hospital dropped to zero, as patients were managed at the PRT-funded Emergency Department of the provincial hospital.10 These PRTs were able to improve access and quality of care available to local populations, whilst supporting health directorate leaders to improve health information systems and health sector governance.

One aim of the PRTs was to extend the legitimacy of the elected government by developing their capacity to deliver essential services to the local population—something that required close cooperation with local leaders and government bodies. This politicisation of aid was not without controversy, and was cited as a contributing factor for NGOs such as Médicin Sans Frontières (MSF) to leave Afghanistan after 24 years of operations there.11

Partnership and Coaching Host Nation Forces

During stabilisation operations, reform of the security sector is undertaken in order to enhance the capability of the government to manage its own security and defence affairs. The recent UK DMS contribution to such an effort has been to work to ensure the host nation military medical services are capable of providing sufficient medical care to sustain their fighting force. During the early stages of the Afghanistan campaign, medical coaching was limited to training Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) medics in Combat Lifesaver and tactical casualty extraction skills. As the conflict progressed, it became necessary to support the ANSF to develop independent field hospitals capable of providing care to their force following the coalition withdrawal. The UK provided the majority of the medical liaison staff to support the establishment of a surgical capability and treatment facility in the ANSF Shorabak Hospital, Helmand, Afghanistan. Whilst considered relatively successful, there were challenges delivering coaching and partnership because of the lack of institutional knowledge in this field.12 Indeed, one of the key lessons identified from the Afghanistan campaign for the future was the need for a capability to develop host nation military medical systems through a multi-agency approach.13 Furthermore, the development of a host nation facility presented ethical challenges during the withdrawal phase – ANSF and civilian casualties were increasingly evacuated to Shorabak, which lacked the technology and infrastructure (in particular critical care support) of Camp Bastion Hospital, raising the possibility that casualties would experience treatment in facilities of varying capability based on their nationality, rather than clinical need as had been the case throughout the campaign.

DHE During Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief Operations

Humanitarian assistance (HA) has been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “aid to an affected population that seeks, as its primary purpose, to save lives and alleviate suffering of a crisis-affected population”.14 The UK Armed Forces have responded to numerous such crises in recent years including natural disasters (the Nepalese Earthquake in 2015 and Hurricane Irma in the Caribbean in 2017), and health crises such as the UN Mission in South Sudan supporting internally displaced persons, and the West African Ebola Crisis, 2014/15.

Relationship Between the Military and NGOs

The majority of HA is provided by non-military affiliated humanitarian Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) who deliver support to affected people based on need, guided by the core humanitarian principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality and independence.15 These principles aim to keep aid separate to all political affiliation, allowing NGOs to negotiate access to all locations and provide support to those most in need. Military forces in contrast are not so readily separated from national or political agendas, and must balance efforts to alleviate suffering with overarching defence, foreign policy and national security objectives. This contrasting approach continues to stimulate debate about how and when military assets should be used to support humanitarian efforts.16,17 As a result, the United Nations Office of Humanitarian Affairs has published guidelines on the use of military assets in HA, including a requirement for HA to retain a “civilian character”, engaging military assets only as a “means of last resort” that is “limited in time and scope” until handover to a civilian agency.18 Military forces do however bring significant capabilities that can be of use during a humanitarian response; this includes a large contingent of rapidly deployable, disciplined and trained personnel with expertise in security, engineering, healthcare and logistics, backed by significant resources and well-established command and control mechanisms. When the impact of a humanitarian crisis outstrips the resources and capabilities of local providers and NGOs, military providers have the capability to make a decisive contribution.

The Ebola Epidemic and Operation GRITROCK

One recent crisis in this context was the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) epidemic that spread from Guinea across West Africa, leading to the largest UK DMS deployment in support of HA for many years. In August 2014 the EVD outbreak became the largest in history. A Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) was declared, calling on the international community to act to contain the epidemic, which stood at over 1000 confirmed cases in four countries and was spreading rapidly. This call to action was echoed by a prominent NGO in the region who called on states to “immediately deploy civilian and military assets with biohazard containment” to curb the epidemic.19 The international community responded, with the UK taking the lead supporting Sierra Leone, the USA undertaking the same for Liberia, and France supporting the effort in Guinea.20 The UK response was a cross-government approach led by the Department for International Development (DfID).21 The UK Armed Forces contribution was known as Operation GRITROCK and focussed on three key areas: (i) training of local healthcare workers; (ii) the provision of UK-quality healthcare to infected healthcare workers; and (iii) strategic support to the Sierra Leonean leaders coordinating the response.20

Within six weeks of the PHEIC being declared, a British Army medical team deployed to Sierra Leone and were helping to deliver training to local staff on the correct use of personal protective equipment (PPE) to prevent transmission, based on an agreed curriculum derived from existing WHO resources. By the time of handover to the International Organisation for Migration in December 2014, the Training Academy had trained 4000 healthcare staff from across the country to WHO standards enabling them to more safely deliver care.22

In Kerrytown, an Ebola Treatment Centre (ETC) had been constructed, co-located with the NGO Save the Children, and was receiving patients within six weeks of activation – the first in-country ETC dedicated to providing care to international and local healthcare workers infected with Ebola. The care provided included advanced techniques usually only available in critical care environments such as ultrasound-guided fluid management and specialised medications delivered via central venous lines.23 The care provided by the ETC was backed by specialist medical support provided by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and Royal Navy. The RAF provided biohazard aeromedical evacuation capable of providing care in transit whilst containing further spread of the virus. The Royal Fleet Auxiliary Ship Argus, as the Primary Casualty Receiving Facility, provided a 100-bed medical treatment facility afloat complete with CT-scanner and specialist medical and surgical support. This significantly higher quality of care and specialist capabilities could not have been provided by local staff or NGOs alone. In this regard, it also contributed significantly to the “moral component” of the mission – providing reassurance to organisations that those willing to volunteer would be well cared for.

At a strategic level, UK military staff were integral to developing the organisational architecture to coordinate the health response, developing the National (NERC) and District Ebola Response Centres (DERC) which gathered data and coordinated activities in partnership with Sierra Leonean colleagues. Military officers and diplomats were deeply embedded in the NERC and worked alongside Sierra Leonean partners developing the healthcare leadership structures, policies and processes to bring the transmission rate to zero, progressively handing over responsibility to the Sierra Leoneans as capacity developed and processes matured.24

Op GRITROCK highlighted that the UK DMS are the only part of the UK health sector that is trained, equipped, manned and available to rapidly deploy and operate a complete medical unit as part of an international response to a health crisis. Through the rapid delivery of healthcare training, and support to healthcare leadership, the military is capable of contributing significantly to the quality of care being delivered and overall effectiveness of the response to a health crisis overseas, before effectively handing over care to civilian partners. Key to success was the ability to work effectively with other government agencies—a skill developed during previous stabilisation operations, added to the deep relationships that existed between the two countries as a result of previous DE activities. Despite concerns that military involvement would deter or endanger NGOs, an article published in Lancet reported that many individuals only returned or established operations once Western governments had announced they were deploying military teams to help contain the epidemic, and that the training and healthcare services provided by the UK military were an important component of the response.25

DHE Outside of Crisis and the Future of Defence Healthcare Engagement

During recent operations, the model for DHE has evolved from ad hoc outreach programmes with limited integration, to a joint multi-agency approach, working at a strategic level alongside local partners. Whether in response to conflict or acute health crisis, the ability of the military to impact healthcare leadership and quality of care overseas is dependent on an understanding of the local healthcare environment. This includes an awareness of the specific health threats, and when they may emerge, the structure of available healthcare provision, and the levers available to policymakers to effect change. This reflects a step change for DMS and sets the challenge to develop the institutional capacity to not only deliver healthcare to UK forces but to engage constructively in health sector reform and quality improvement programmes with partner nations in a wide variety of political and economic contexts.

Centre for Defence Healthcare Engagement

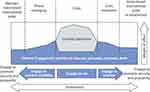

The Centre for DHE was established in 2015 to coordinate these efforts and share best practice with partners and allies.26 As a non-contentious, relatively politically low-risk activity with broad support, DHE can play an important role in helping to establish and develop links with other nations. Through coaching and quality improvement programmes with partners overseas, the UK may be able to identify growing instability or health crises and be better placed to respond to help resolve the situation. In this way, DHE makes a contribution across the spectrum of security stages (Figure 2).27

|

Figure 2 Defence Engagement throughout the spectrum of international security stages. Reproduced with permission from Ministry of Defence. Joint doctrine note 1/15: defence engagement. 2015. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/570579/20160104-Defence_engagement_jdn_1_15.pdf.2 |

Partnership in Pakistan

The first DHE task coordinated by the Centre for DHE involved a team of UK DMS doctors and nurses deploying to a 1000-bed hospital in Pakistan to work alongside host nation healthcare workers. The focus of the engagement was on peer-to-peer engagement and understanding with emphasis on education, quality improvement process and female empowerment. Utilising the DMS nursing development model (Figure 3), UK DMS supported the Pakistani team as they developed their organisational culture to ensure that everyone felt able to contribute to safety and quality improvement initiatives. This was particularly important for nurses, who had not previously felt empowered to engage in quality improvement work in a doctor-centric environment.

|

Figure 3 The DMS nursing development model. Adapted from Lamb D, Hofman A, Clark J, Hughes A, Sukhera AM. Taking a seat at the table: an educational model for nursing empowerment. Int Nurs Rev. 2019. © 2019 Crown copyright. International Nursing Review © 2019 International Council of Nurses.28 |

This was achieved through an education programme, the introduction of practice development nurses, and a “model ward” that was staffed and structured to demonstrate what could be achieved by appropriately engaged and supported nursing staff. The ward was led by a senior Pakistani nurse who was coached by UK DMS nurses experienced in ward management and quality improvement. It was staffed by a mix of UK DMS and Pakistani nurses who worked together to deliver patient care in a culture of constant quality improvement. Nurses visited for short placements from other healthcare facilities and left feeling better able to lead change in their own hospitals.28 Initial quality improvement programmes (QIPs) centred on compliance with WHO hand hygiene guidance, surveillance for hospital-associated infections related to indwelling venous catheters and engagement with the WHO Safer Surgery project. Each QIP demonstrated significant and sustained improvement during the deployment, raising the quality of care and helping to prevent hospital-associated infections. During the deployment, new quality improvement targets were identified, host quality improvement champions were identified and a hospital oversight committee was established to help sustain improvement and identify new areas for development.29

Leadership in the Defence Medical Services

Leadership within Defence is embedded within the concept of command – the authority vested in an individual of the armed forces for the direction, coordination and control of military forces. Command is understood to incorporate three functions – leadership, decision-making and control30 (Figure 4). These functions form the basis of military command, leadership and management training which is a core component of career development for DMS personnel.

|

Figure 4 Functions of command. Reproduced with permission from Ministry of Defence. Army doctrine publication: land operations. 2019. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/605298/Army_Field_Manual__AFM__A5_Master_ADP_Interactive_Gov_Web.pdf.31 |

The manner in which command is exercised—the command philosophy—used by UK military commanders (including within the DMS) is known as mission command. This philosophy is “founded on a clear expression of intent by commanders, and the freedom of subordinates to act to achieve that intent”31 In other words, members of the team are given a clear picture of the intended outcome and boundaries within which they must act, then empowered to take appropriate actions to achieve the task, using initiative to respond to changing local circumstances as they deem necessary. The approach is designed to allow commanders the flexibility to respond to a rapidly evolving battlefield but is equally relevant to the dynamic environment of acute healthcare. Whether developing Ebola Response Centre strategy in Sierra Leone, or implementing nurse-led quality improvement projects in Pakistan, it can be argued that the application of the philosophy of mission command underpins much of the early success in DHE. In each case, DMS personnel supported host nation teams to develop clear objectives, set boundaries for action, and then provided coaching whilst local teams completed the task, utilising deep local knowledge of the healthcare environment to respond to local challenges as they saw fit. In this way, the external expertise of DMS staff (in planning, command and control and quality improvement methodologies) has helped maximise the potential of local actors to deliver lasting change. In return, DMS staff developed skills in cross-cultural communication, strategic planning and change management – useful skills for implementing change in NHS practice and defence healthcare alike.

Conclusion

There is increasing involvement of military forces in healthcare overseas as part of a Defence Healthcare Engagement strategy. The unique capabilities of the military have the potential to facilitate improvements in healthcare leadership and quality of care. This is particularly the case where large-scale deployments are required to rapidly scale up healthcare training, provision and coordination in response to an unprecedented health crisis outstripping the capacity of host nation health sectors. During conflict and stabilisation, the impact on healthcare can be significant but must be balanced against the potential to undermine local healthcare provision and endanger humanitarian providers through the politicisation of aid. Military support may therefore be best limited to infrastructure support and indirect assistance—delivered in partnership with aid agencies and local partners—or the development of the security sector via coaching of host nation military medical services. Outside of a crisis response, DHE can enhance bilateral cultural understanding, facilitate peaceful co-operation and healthcare quality improvement, benefiting the UK and international partners alike.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Ministry of Defence. UK’s international defence engagement strategy. 2017. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/596968/06032017_Def_Engag_Strat_2017DaSCREEN.pdf.

2. Ministry of Defence. Joint doctrine note 1/15: defence engagement. 2015. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/570579/20160104-Defence_engagement_jdn_1_15.pdf.

3. Bricknell M, Sullivan R. The centre for defence healthcare engagement: a focus for defence engagement by the defence medical services. J R Army Med Corps. 2018;164(1):5–7. doi:10.1136/jramc-2017-000798

4. Dixon P. ‘Hearts and minds’? British counter-insurgency from Malaya to Iraq. J Strateg Stud. 2009;32(3):353–381. doi:10.1080/01402390902928172

5. Owens MD, Rice J, Moore D, Adams AL, Global Health A. Engagement Success: applying evidence-based concepts to create a rapid response team in Angola to Combat ebola and other public health emergencies of international concern. Mil Med. 2019;184(5–6):113–114. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz005

6. Cameron EA. Do no harm - the limitations of civilian medical outreach and MEDCAP programmes based in Afghanistan. J R Army Med Corps. 2011;157(3):209–211. doi:10.1136/jramc-157-03-02

7. Wilson RL, Moawad FJ, Hartzell JD. Lessons for conducting health development at the tactical level. Mil Med. 2015;180(4):368–373. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00319

8. Bebber RJ. The Role of Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) in counterinsurgency operations: Khost Province, Afghanistan. Small Wars J. 2008;10:1–18.

9. HM Government. The UK’s work in Afghanistan. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uks-work-in-afghanistan/the-uks-work-in-afghanistan#development-in-helmand-province-since-2006.

10. Malkasian C, Meyerle G. Provincial Reconstruction Teams: How Do We Know They Work? Fort Belvoir, VA: Defense Technical Information Center; 2009. doi:10.21236/ADA496359

11. MSF pulls out of Afghanistan. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International. Available from: https://www.msf.org/msf-pulls-out-afghanistan.

12. Vassallo D. A short history of camp bastion hospital: the two hospitals and unit deployments. J R Army Med Corps. 2015;161(1):79–83. doi:10.1136/jramc-2015-000414

13. Bricknell MCM, Nadin M. Lessons from the organisation of the UK medical services deployed in support of operation TELIC (Iraq) and operation HERRICK (Afghanistan). J R Army Med Corps. 2017;163(4):273–279. doi:10.1136/jramc-2016-000720

14. World Health Organization. Glossary of humanitarian terms. 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/hac/about/reliefweb-aug2008.pdf?ua=1.

15. Horne S, Burns DS. Medical civil–military interactions on United Nations missions: lessons from South Sudan. J R Army Med Corps. 2019;

16. Michaud J, Moss K, Licina D, et al. Militaries and global health: peace, conflict, and disaster response. Lancet. 2019;393(10168):276–286. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32838-1

17. Bristol N. Military incursions into aid work anger humanitarian groups. Lancet. 2006;367(9508):384–386. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68122-1

18. United Nations. Guidelines on the use of foreign military and civil defence assets in disaster relief. Available from: https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/OSLO%20Guidelines%20Rev%201.1%20-%20Nov%2007_0.pdf.

19. Forestier C, Cox AT, Horne S. Coordination and relationships between organisations during the civil–military international response against ebola in sierra leone: an observational discussion. J R Army Med Corps. 2016;162(3):156–162. doi:10.1136/jramc-2015-000612

20. Bricknell M, Hodgetts T, Beaton K, McCourt A. Operation GRITROCK: the defence medical services’ story and emerging lessons from supporting the UK response to the ebola crisis. J R Army Med Corps. 2016;162(3):169–175. doi:10.1136/jramc-2015-000512

21. HM Government. UK action plan to defeat ebola in sierra leone. 2014. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/357569/UK_action_plan_to_defeat_Ebola_in_Sierra_Leone_-_background_paper.pdf.

22. Eardley W, Bowley D, Hunt P, Round J, Tarmey N, Williams A. Education and ebola: initiating the cascade of emergency healthcare training. J R Army Med Corps. 2016;162(3):203–206. doi:10.1136/jramc-2014-000394

23. Rees P, Ardley C, Bailey M, et al. Operational. Op GRITROCK: the royal navy supports defence efforts to tackle ebola. J R Nav Med Serv. 2014;100(3):228.

24. Ross E. Command and control of sierra leone’s ebola outbreak response: evolution of the response architecture. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2017;372(1721):1721. doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0306

25. Kamradt-Scott A, Harman S, Wenham C, Smith F. Civil–military cooperation in Ebola and beyond. Lancet. 2016;387(10014):104–105. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01128-9

26. Ministry of Defence. SDSR 2015 defence fact sheets. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/492800/20150118-SDSR_Factsheets_1_to_17_ver_13.pdf. 2015.

27. Whitaker J, Bowley D. Beyond bombs and bayonets: defence engagement and the defence medical services. J R Army Med Corps. 2019;165(3):140–142. doi:10.1136/jramc-2017-000838

28. Lamb D, Hofman A, Clark J, Hughes A, Sukhera AM. Taking a seat at the table: an educational model for nursing empowerment. Int Nurs Rev. 2019. doi:10.1111/inr.12549

29. Bowley DM, Lamb D, Rumbold P, Hunt P, Kayani J, Sukhera AM. Nursing and medical contribution to defence healthcare engagement: initial experiences of the UK defence medical services. J R Army Med Corps. 2019;165(3):143–146. doi:10.1136/jramc-2017-000875

30. Ministry of Defence. JDP 01: UK joint operations doctrine. 2014. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/389755/20141208-JDP_0_01_Ed_5_UK_Defence_Doctrine.pdf.

31. Ministry of Defence. Army doctrine publication: land operations. 2019. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/605298/Army_Field_Manual__AFM__A5_Master_ADP_Interactive_Gov_Web.pdf.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.