Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 9

Current perspectives on the role of body painting in medical education

Authors Finn GM

Received 18 May 2018

Accepted for publication 31 July 2018

Published 25 September 2018 Volume 2018:9 Pages 701—706

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S142212

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Gabrielle M Finn

Health Professions Education Unit, Hull York Medical School, University of York, York, UK

Abstract: Body painting is a popular teaching and learning tool within medical education. Art-based approaches, such as body painting, allow students to learn in a fun and engaging manner. They are particularly useful for students who struggle with cadaveric study of anatomy. Body painting is not only limited to use for anatomical study, but it can also be beneficial as a mechanism for introducing clinical examination and associated communication skills. The use of vibrant color adds to its appeal and is often cited as the mechanism through which students effectively learn.

Keywords: anatomy, medical education, art, surface anatomy, body painting, medical student

Review

Curricula reforms, governance and policy changes have all driven changes in medical education.1,2 Specifically, within anatomy education there is an ongoing evolution in the teaching methods utilized. These changes are in response to a number of factors including fewer cadavers, time constraints, reduced budgets and limited numbers of trained staff.3 Furthermore, agendas to promote student experience and relate teaching to the future clinical practice have motivated anatomists to formulate new approaches to teaching.1 At many institutions globally, the use of pre-dissected cadaveric specimens (prosection) has replaced student-led dissection; self-directed learning has replaced formal instructor-led teaching. In order to counter the aforementioned challenges, institutions now opt to use methods of teaching that are novel and innovative.4 These are frequently adapted from outside of the medical context and include wearable anatomical garments, virtual dissection, clay modeling and life drawing classes. These methods are all reported to add a new dimension to the classroom.1 Among the most well researched and popular approaches is body painting.

The origins of body painting stem from tribal cultures where it was used for ceremonial purposes and it is an ancient form of art.1,5,6 Within the context of popular culture and entertainment, the face is most frequently painted with typical examples being seen at events such as children’s parties or within the sports arena. In recent years, body painting has been used within the medical field.1,7–12

Within medical education literature, body painting is described as the process of painting internal structures on the surface of the body, typically with a high degree of detail.9 During teaching back in 1999, Op Den Akker et al9 first used body painting, described as the painting of internal structures on the surface of the human body with high verisimilitude. Demarcating the body is not new, marking the body with simple outlines can be traced back at least a century,13 the body painting described by Op Den Akker9 significantly differs from this in terms of detail. Paintings range from simple outlines of viscera and demarcations of bones or vasculature9,14 to the marveled and works of artists such as Danny Quirk,15,16 the latter more widely used for public engagement than traditional anatomy education.

In the decades since Op Den Akker’s seminal paper,9 many have supported the use of body painting within the anatomical education setting, in particular, the efficacy of its use in conjunction with clinical skills and peer-examination,10–12,17–19 both procedures underpinned by a sound knowledge of surface anatomy.

Surface anatomy

Surface anatomy is defined as the anatomical structures or features that are identifiable on the outside of the body as surface projections. These might include, for example, bony landmarks or musculature. An understanding of the surface anatomy and markings of the body is imperative when introducing clinical sciences.20,21 Ganguly20 describes how an obvious connection is formed between basic gross anatomy and clinical practice through surface anatomy, as surface anatomy is the basis of physical examination.18

Some institutions have reported the primary learning method for surface anatomy as being the demarcation of such structures on cadavers,8 however, this is not common practice in current medical education. Historically, gross anatomy has been taught by either dissection or the use of prosections.1 Cadaveric anatomical study is useful for studying the anatomy of viscera22 and provides an opportunity for an overview of spatial orientation.23,24 The issue with a reliance on cadaveric anatomy is that, within clinical practice, human anatomy is typically encountered by health care professionals in the living form or via common forms of medical imaging such as X-ray.25 In response to a call for anatomy teaching to reflect the clinical context, there has been a shift to engage students in learning opportunities which provide an increased emphasis upon living anatomy; body painting being a prime example of this. Within literature there has been a culture of blame, whereby clinical colleagues often accuse anatomists of teaching students too much detail and not spending enough time teaching the structures they perceive to be most clinically relevant,26 body painting allows the clinical relevance of the gross anatomy to be emphasized to students. Body painting is of particular use as a method for introducing students to surface anatomy within the classroom. Painting complements the teaching of a number of clinical skills, including palpation and auscultation.7,9,11 Surface anatomy is a way of bringing cadaveric anatomy to life1,27 and body painting helps to achieve that goal. Similarly, body painting has been reported as a tool to make learning surface anatomy more interesting and enjoyable.1,8 Furthermore, the process enables students to connect anatomical structures with clinical diagnoses and thus excel during their subsequent clinical practice.8

Within literature, teaching sessions which contain body painting are described as frequently requiring students to palpate bony landmarks in order to demarcate the associated anatomical structures. Some papers attribute this process of painting and examining as being beneficial for future clinical practice.1,7–9,11,12,28,29 Moreover, many body features such as the boundaries of the lobes of the lungs or positions of the different heart valves can be painted on to a volunteer; a subsequent clinical examination can be performed such as listening to the heart or lungs with the stethoscope. When students are dealing with simulated patients, healthy volunteers or their peers, who may be required to be in a state of undress and are completing palpation and examination they must communicate in an appropriate manner, empathize with their volunteer canvas, and approach them with professionalism; thus, the clinical skills required in the workplace environment are developed during participation. Such body painting sessions allow integration between anatomy and clinical examination skills and thus ensure the future patient is at the epicenter of teaching.

A key example of the use of body painting for the purposes of learning surface anatomy include the osteology of the hand. This example demonstrates how individuals can either paint on to their own skin, rather than having to work in pairs, or can paint a peer. The hand is an easily accessed area of the body, the painting of which does not require undressing. It has been reported as being a painting activity ideal for use with outreach and groups of school children, recruitment days or for other types of public engagement or widening access events.1

The nature of learning associated with body painting

Color and the fun nature of body painting are consistently linked to its success as a tool within anatomy education.1,11,12,19,28 Qualitative data has shown that students attribute memorization of the associated anatomy to the use of bold color.11 Literature also reports the perceived value of body painting as a learning tool as being derived from the kinesthetic nature6,7,11 of the painting process. It is thought to be the active participation and kinesthetic nature of body painting, alongside the visually striking and thus, memorable imagery of the associated underlying anatomy, that contribute to its positive reputation as a successful learning tool.7,9,11,25

Body painting is reported by students to be a highly motivating exercise.11 A significant advantage for students is reported to be the creation of what could be called “learning landmarks”: “vivid experiences which are memorable in themselves, and which then provide access to the educational content associated within that context”.11 Students report acquiring a good understanding of both the dimensionality and positions of anatomical structures while using body painting.9 Current research supports the position that body painting is a memorable exercise that provides students with an understanding of the link between the differing visual, tactile and auditory elements of anatomy.17

Retention of anatomical knowledge is one of the most educationally advantageous attributes of body painting. Through active engagement in the process of painting, rather than passive learning in a traditional didactic teaching session, students’ learning transitions from surface to deep.11 The use of bold color aids the students’ memory of the painted.8,19 The multi-sensory painting process utilizes all learning styles and approaches simultaneously as students visualize, paint (kinesthetic), read aloud the instructions (auditory) and for the student who acts as the canvas, they feel the paint on their own skin (sensory). Thus, students claim that retention of knowledge is promoted. An additional source of positive impact on recall stems from the fact that students often photograph their painting for revision and sentiment.1 Studies to statistically measure the retention of knowledge using body painting have shown limited results.10,30 Jariyapong et al, found that there was no statistically significant difference in knowledge retention between control and experimental groups using body paint to learn anatomy of the hand.30 Finn et al also reported that there was no difference in retention of knowledge over the long-term between those who only used black outlines and those who used color when learning abdominal anatomy.10 That being said, in both studies students remained advocates of using body painting and were unanimous in their attributing body painting to be an asset when retaining anatomical knowledge

Non-anatomical lessons

Body painting is not only utilized for teaching surface anatomy and clinical examination, but also provides a platform for the development of other skills.11,21,30 These skills are frequently related to the conduct of the student, and the future professional role they aspire to have.11,19,28 They include communication skills, appropriate professional touch and examination skills, as well as the development of associated scripts to request undressing within clinical examinations.

Aka et al, argue that the non-anatomical skills developed when students utilize body painting are primarily developed through the hidden curriculum.28 The social processes associated with the act of body painting provide a mechanism by which the hidden curriculum can be exposed, considered and reflected upon.28 The hidden curriculum is the unplanned curriculum transmitting tacit messages to students on values, attitudes, principles and organisation.28,31 It is comprised of multiple facets which often include organizational and institutional contexts. In addition, the cultural subtexts that shape both what and how students learn outside the formal anatomy and intended anatomy curriculum are encompassed.28,31,32

A recent qualitative study28 explored faculty perceptions of the use of body painting as a teaching tool, finding that the hidden curriculum appeared spontaneously as a major advantage of utilizing painting. From their data, four major themes emerged; trait development, socialization, tacit learning and script formation. Anatomy education lends itself to an environment in which one can study the hidden curriculum. The hidden curriculum encompasses things that are learned but not openly intended including behaviors, values and social practices28 – things that body painting sessions are sometimes reported to develop. Results from Aka’s study demonstrated faculty awareness of, and deliberate use of, the hidden curriculum as a method to “teach by stealth”, meaning that they exploited the painting sessions as a way to deliver professionalism teaching without didactic input. By actively employing the hidden curriculum they were pushing at the boundaries of the hidden curriculum concept as it is hard to manipulate something that is meant to be hidden by its very nature.

Aka et al, reported the development of professionalism as a trait, mostly through the process of peer examination and the doctor patient style encounter that body painting requires.28 This mirrors the findings of Finn and McLachlan in 2010, who explored the student viewpoint.11 Aka et al28 asserted that it is suggested that through peer examination and being subjected to tacit messages through the hidden curriculum, coupled with learning from peers by socialization, students become more confident in themselves when adopting the role of a doctor and approaching patients. They conclude that opportunities to undertake body painting activities are therefore imperative within an anatomy curriculum.28

Body painting is reported to be a valuable tool for diminishing the anxiety frequently exhibited by students when conducting physical examinations, particularly with peers.7 A fear of death may be oppressive for students when studying in dissection room and may be correlated to poor academic performance; using alternative approaches, such as body painting could, therefore, present a beneficial learning opportunity for students who struggle with cadaveric work.10,11,33 These attributes may not be the intended learning outcomes of a body painting session but are useful by products of the experience.

In a study looking at the general use art-based approaches (drawing, creative writing and drama) within medical education, students reported that arts made a valued contribution to the medical curriculum.34 In particular, students felt the arts training could reduce performance anxiety in situations such as new placements, during examinations or even presentations. The study reported that the group work involved in art-based approaches helped students to develop camaraderie.34 Similarly, advocates of body painting praise key features such as a positive learning environment and close working relationships that body painting helps to establish.1,8,11

Utility

Body painting is deemed to be cost effective.1,30,35 This is an important consideration for any institution considering implementing a new teaching method. Paints are inexpensive, and paint brushes and pots can be reused. All materials are readily available.12 Entirely new supplies are also not a necessity as old storage containers can be used for water pots; the brushes do not need to be special.1 Makeup products such as eyeliners can also be used, again making cost non-prohibitive.12,36 As for the delivery of body painting teaching sessions, studies report that large numbers of students can engage with the activity at the same time meaning iterative cycles of teaching are not required. Furthermore, students require minimal direction once instruction sheets have been disseminated, thus it is effective in terms of both staff time, cost and physical resources.1,30

Another well cited advantage of body painting is that it promotes a positive learning environment.7,11,19 Reserved students find it difficult not to positively engage with body painting sessions,1 body painting helps establish positive relationships with peers.8,19 The activity is fun and therefore becomes a welcome break from the tedium of the traditional learning environments such as the dissecting room or lecture theater. There is no longer a need to rely on cadavers which have restricted access issues associated with their use8 as body painting can be conducted outside of the classroom setting. This can be particularly beneficial for students who struggle with cadaveric work and the notion of death.

Student enjoyment creates a positive learning environment and peer-lead teaching typically results.8 Body painting is not a didactic modality for teaching delivery, therefore, it can create a positive and relatively relaxed set of relationships within the classroom between faculty and students alike.1 This is similar to reports from other art-based group work within medical education, such as drama and creative writing34 where group work promoted camaraderie and thus a positive environment.

A major advantage associated with the use of body paint is that it offers an alternative to cadaveric study when learning gross anatomy.1,8 Understandably, the dissecting room is an alien environment and it can be an environment in which students who have emotional difficulties with cadaveric material may find both challenging and hostile. Learning taking place outside the dissecting room context can be beneficial for such students educationally and from a student support perspective.1 Another limitation with cadaveric anatomy is that surface anatomy is difficult to demonstrate on prosections and whole cadavers, thus body painting is useful; it places emphasis upon living anatomy throughout and can be conducted on a range of living bodies with differing morphologies. When time is limited for active dissection, cadaveric material or laboratory access are in limited supply, educators may consider implementing body painting into their curricula. While body painting cannot entirely replace cadaveric study, it has a powerful role to play in emphasizing the living nature of anatomy.1

As with all learning tools, body painting has its limitations. Firstly, it is a time-consuming exercise8 as painting require time to apply, as well as the time associated with delivering any related teaching and for students to change clothing and clean up. This can be countered by utilizing body painting within a flipped classroom approach. Additionally, there are obvious religious and cultural issues related with the need to undress for some painting activities.12 Recommendations in literature suggest that same sex groups, painting on top of old clothing, chaperones and allowing students to choose their peer group for activities helps maximize participation in such instances.

Body painting isn’t suitable for everything; it is well suited for large, superficial structures such as muscles. It is more limited for demarking the relationship between structures.9 Documented use includes dermatomes, neurovasculature, areas of referred pain and musculoskeletal anatomies.1,7,9 It is important to emphasize that body painting is not an ideal method for teaching gross anatomy in isolation, but more for providing context and application, as well as a method by which to introduce surface anatomy. It is best used as an adjunct as opposed to a sole teaching modality. A further consideration is that painting is messy both in terms of the physical classroom environment and the students’ bodies. Time and resource needs need to be factored in for cleaning the room and equipment. Additionally, students may need to remove paintings from their skin before leaving a session.

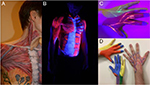

Another disadvantage is that the neutral and lighter colored paints are often difficult to see on some skin tones.1,6 This can be addressed by offering a wide range of colors for students to work with or by working with ultraviolet (UV) paints. UV fluorescent body paints can be used as an adjunct to regular body paints (non-fluorescent). They offer the advantage of being able to layer and thus show superficial and deep structures simultaneously. The limitation is that using UV light has obvious health and safety considerations and thus its use should be limited. UV paint is more visually striking than normal paints and overuse could limit its impact and thus use in a limited capacity is recommended. For example, demonstrations of multilayer anatomy (superficial/deep) or functional anatomy are most appropriate. Examples of normal and UV body paintings are shown in Figure 1.

Conclusion

Anatomical body painting is an effective and popular art-based approach to anatomy education.1 Its popularity is based upon its adaptability as a tool for learning both gross and surface anatomy, as well as for introducing clinical examination skills. Through active engagement coupled with the use of bold color, students report that it promotes long-term retention of knowledge. The assumed hidden curriculum of body painting is reported to encourage students to develop professional attributes such as communication skills and professional conduct. In addition, students confront issues associated with clinical examination including vulnerability and body image, in a positive, fun, safe and stimulating learning environment.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Finn G. Using body painting and other art-based approaches to teach anatomy. Teaching Anatomy: A Practical Guide. Chan LK, Pawlina W, editors. Germany: Springer; 2015:155–164. | ||

Drake RL, Mcbride JM, Lachman N, Pawlina W. Medical education in the anatomical sciences: the winds of change continue to blow. Anat Sci Educ. 2009;2(6):253–259. | ||

Drake RL. Anatomy education in a changing medical curriculum. Anat Rec. 1998;253(1):28–31. | ||

Azer SA, Eizenberg N. Do we need dissection in an integrated problem-based learning medical course? Perceptions of first- and second-year students. Surg Radiol Anat. 2007;29(2):173–180. | ||

Hintner M. Bodypainting; 2008. | ||

Finn GM. Twelve tips for running a successful body painting teaching session. Med Teach. 2010;32(11):887–890. | ||

Mcmenamin PG. Body painting as a tool in clinical anatomy teaching. Anat Sci Educ. 2008;1(4):139–144. | ||

Nanjundaiah K, Chowdapurkar S. Body-painting: a tool which can be used to teach surface anatomy. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6(8):1405. | ||

Op den Akker JW, Bohnen A, Oudegeest WJ, Hillen B. Giving color to a new curriculum: bodypaint as a tool in medical education. Clin Anat. 2002;15(5):356–362. | ||

Finn GM, White PM, Abdelbagi I. The impact of color and role on retention of knowledge: a body-painting study within undergraduate medicine. Anat Sci Educ. 2011;4(6):311–317. | ||

Finn GM, Mclachlan JC. A qualitative study of student responses to body painting. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3(1):33–38. | ||

Finn GM. Twelve tips for running a successful body painting teaching session. Med Teach. 2010;32(11):887–890. | ||

Eisendrath D. A Text-book of Clinical Anatomy. 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 1904. | ||

Cody J. Painting anatomy on anatomy. J Biocommun. 1995;22(2):14–17. | ||

Quirk D. Immaculate Dissection. Available from: https://www.immaculatedissection.com. Accessed July 4, 2018. | ||

Bennett C. Anatomic body painting: where visual art meets science. J Physician Assist Educ. 2014;25(4):52–54. | ||

Mclachlan JC, Regan de Bere S. How we teach anatomy without cadavers. The Clinical Teacher. 2004;1(2):49–52. | ||

Sugand K, Abrahams P, Khurana A. The anatomy of anatomy: a review for its modernization. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3(2):83–93. | ||

Cookson NE, Aka JJ, Finn GM. An exploration of anatomists’ views toward the use of body painting in anatomical and medical education: An international study. Anat Sci Educ. 2018;11(2):146–154. | ||

Ganguly P, Chan L. Living anatomy in the 21st century: how far can we go? South East Asian Journal of Medical Education. 2008;2:52–57. | ||

Ganguly PK. Teaching and Learning of Anatomy in the 21st Century: Direction and the Strategies. The Open Medical Education Journal. 2010;3. | ||

Parker LM. Anatomical dissection: why are we cutting it out? Dissection in undergraduate teaching. ANZ J Surg. 2002;72(12):910–912. | ||

Mccormack WT, Lazarus C, Stern D, Small PA. Peer nomination: a tool for identifying medical student exemplars in clinical competence and caring, evaluated at three medical schools. Acad Med. 2007;82(11):1033–1039. | ||

Granger NA. Dissection laboratory is vital to medical gross anatomy education. Anat Rec B New Anat. 2004;281(1):6–8. | ||

Mclachlan JC, Patten D. Anatomy teaching: ghosts of the past, present and future. Med Educ. 2006;40(3):243–253. | ||

Pabst R. Gross anatomy: an outdated subject or an essential part of a modern medical curriculum? Results of a questionnaire circulated to final-year medical students. Anat Rec. 1993;237(3):431–433. | ||

Aggarwal R, Brough H, Ellis H. Medical student participation in surface anatomy classes. Clin Anat. 2006;19(7):627–631. | ||

Aka JJ, Cookson NE, Hafferty F, Finn GM. Teaching by stealth: utilising the hidden curriculum through body painting within anatomy education. European Jounral of Anatomy. 2018;22(2):173–182. | ||

Cookson NE, Aka JJ, Finn GM. An exploration of anatomists’ views toward the use of body painting in anatomical and medical education: An international study. Anat Sci Educ. 2018;11(2):146-154–154. | ||

Jariyapong P, Punsawad C, Bunratsami S, Kongthong P. Body painting to promote self-active learning of hand anatomy for preclinical medical students. Med Educ Online. 2016;21:30833. | ||

Hafferty FW, Finn GM. The hidden curriculum and anatomy education. Teaching Anatomy. Springer; 2015:339–349. | ||

Lempp H, Seale C. The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: qualitative study of medical students’ perceptions of teaching. BMJ. 2004;329(7469):770–773. | ||

Skidmore JR. The case for prosection: comment on R.L.M. Newell’s paper. Clin Anat. 1995;8(2):128–130. | ||

de La Croix A, Rose C, Wildig E, Willson S. Arts-based learning in medical education: the students’ perspective. Med Educ. 2011;45(11):1090–1100. | ||

Estai M, Bunt S. Best teaching practices in anatomy education: A critical review. Ann Anat. 2016;208:151–157. | ||

Bergman EM, Sieben JM, Smailbegovic I, de Bruin AB, Scherpbier AJ, van der Vleuten CP. Constructive, collaborative, contextual, and self-directed learning in surface anatomy education. Anat Sci Educ. 2013;6(2):114–124. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.