Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 13

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Systematic Review

Authors Khalili F , Najafi B , Mansour-Ghanaei F , Yousefi M, Abdollahzad H , Motlagh A

Received 26 May 2020

Accepted for publication 22 July 2020

Published 10 September 2020 Volume 2020:13 Pages 1499—1512

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S262171

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Marco Carotenuto

Farhad Khalili,1 Behzad Najafi,2 Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei,3 Mahmood Yousefi,4 Hadi Abdollahzad,5 Ali Motlagh6

1Department of Health Economics, School of Management and Medical Informatics, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran; 2Iranian Center of Excellence in Health Management, School of Management and Medical Informatics, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran; 3Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran; 4Department of Health Economics, Iranian Center of Excellence in Health Management, School of Management and Medical Informatics, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran; 5Research Center for Environmental Determinants of Health, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran; 6National Cancer Control Secretariat, Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Tehran, Iran

Correspondence: Mahmood Yousefi Email [email protected]

Introduction: Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a significant health problem with an increasing incidence worldwide. Screening is one of the ways, in which cases and deaths of CRC can be prevented. The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the different CRC screening techniques and to specify the efficient technique from a cost-effectiveness perspective.

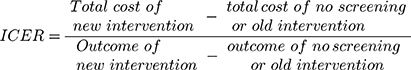

Methods: The economic studies of CRC screening in general populations (average risk), aged 50 years and above were reviewed. Two reviewers independently reviewed the titles, abstracts, and full-texts of the studies in five databases: Cochrane, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science and PubMed. The disagreements between reviewers were resolved through the authors’ consensus. The main outcome measures in this systematic review were the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of screening versus no-screening and then in comparison with other screening techniques. The ICER is defined by the difference in cost between two possible interventions, divided by the difference in their effect.

Results: Eight studies were identified and retained for the final analysis. In this study, when screening techniques were compared to no-screening, all CRC screening techniques showed to be cost-effective. The lowest ICER calculated was $PPP − 16265/quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) (the negative ICERs were between purchasing power parity in US dollar ($PPP) − 16265/QALY to $PPP − 1988/QALY, whereas the positive ICERs were between $PPP 1257/QALY to $PPP 55987/QALY). For studies comparing various screening techniques, there was great heterogeneity in terms of the structures of the analyses, leading to diverse conclusions about their incremental cost-effectiveness.

Conclusion: All CRC screening techniques were cost-effective, compared with the no-screening methods. The cost-effectiveness of the various screening techniques mainly was dependent on the context-specific parameters and highly affected by the framework of the cost-effectiveness analysis. In order to make the studies comparable, it is important to adopt a reference-based methodology for economic evaluation studies.

Keywords: incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, screening techniques, economic evaluation, colorectal cancer

Introduction

Among the world mostly diagnosed cancers, colorectal cancer (CRC) takes the third place in males and the second in females, worldwide.1

In 2018, there were an estimated 1.8 million new CRC cases and 861,663 deaths in both sexes at all ages (0–85+ years). This is already becoming a major public health problem across the world.1,2 The attributable cases and deaths of CRC can be avoided through early diagnosis. Screening for finding cases at the early stages of the disease is a well-known strategy of controlling disease, in fact, early detection of cancer helps to remove precancerous lesions and prevent cancer from reaching advanced stages. While the European Union recommends screening by a fecal occult blood test (FOBT), in the US the guidelines recommend people older than 50 years, to choose among several recommended strategies.3,4

Screening programs often target people with apparently healthy conditions, and active screening tends to be delivered collectively. Thus, the number of people using screening services is usually higher than the true number of patients. This in turn has implications for high costs per diagnosed patient. In an optimal situation, the return of benefits to society due to the implementation of screening should outweigh the associated costs. In essence, understanding this situation depends on some basic factors like the prevalence of the disease, accuracy of screening methods, target population, and cost of each strategy.5 Economic evaluation is a systematic and formal way of assessing the costs and benefits of screening interventions. There are several techniques for screening of CRC; colonoscopy, which is one of the most popular interventions, has been associated with relatively high but better accuracy performance;6 in contrast, the FOBT has advantages over colonoscopy in terms of being less costly and easy to perform. The fecal immunochemical test (FIT), which is also called either immunochemical FOBT or IFOBT, is usually favored because it does not need any dietary restriction, and it has higher specificity when it is compared to guaiac-based FOBT (G-FOBT).7,8 Furthermore, the non-invasive hybrid screening techniques, which is a stool DNA test (S-DNA test), have recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).9,10 The characteristics of different types of screening techniques are presented in Appendix 1.

We performed a systematic review to retrieve the evidence on the cost-effectiveness of the various CRC screening methods. The study was designed to focus on the most recent studies, which have been conducted worldwide, since 2012.

This review aimed to explore the cost-effectiveness of the different screening strategies, either in comparison with no-screening or other techniques, in the average-risk population.

Methods

Search Strategy

We conducted this systematic review based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines,11 and following the Cochrane Handbooks for systematic reviews.12 The search strategy used in this review was registered in Prospero13 (registration number: CRD42018081676). The approach for identifying studies and extracting the data has been described in earlier studies, and performed in the economic evaluation of CRC screening techniques.14,15 Five databases were searched for identifying relevant studies, including Cochrane, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed. We used a specific search strategy for each database and the following key terms were used: “colorectal cancer”, “cost-effectiveness” and “screening”. Our search was restricted to studies written in English and published between January 2012 and December 2018, and then updated until June 2020. In order to find the studies not covered by our database searches and studies in gray literature, we manually looked at the reference lists of the studies and contacted the authors of the concerned studies. The studies were chosen, according to the similar inclusion and exclusion criteria, as in the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) review.16

The inclusion criteria were: 1) Studies that focused on CRC screening, 2) Studies that aimed at average risk17 populations, aged 50 years and above, 3) Studies that reported the Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER) or provided data for ICER calculation, 4) Studies that outlined cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained or cost per life-year gained, 5) Studies that had full economic evaluations, and 6) Studies published in English.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) Articles that reported only cost per cancer detected, cost per patient screened and cost per death prevented, 2) Non-original studies, 3) Opportunistic screening, and 4) Short-term decision trees.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Firstly, two reviewers independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies and then excluded the irrelevant studies based on the developed criteria. When the articles could not be located based on the title and abstract, the full-text was evaluated. The disagreements between reviewers about inclusion and exclusion of studies were resolved through the authors’ consensus or by the third reviewer. For data collection, we designed a data extraction form containing 1) Details of bibliography, 2) Study design, including aim and cases of studies, time horizon, interventions and alternatives, costs included in the study, sources of screening cost, outcome measures for effectiveness, data sources that are relevant to the outcome, study’s perspective, modeling sensitivity analysis and discount rate for both costs and outcomes, and 3) Main results and conclusions. Data extracted from each article were included in the table for each of the techniques under consideration such as FIT, Flexible Sigmoidoscopy (FS), FOBT, Multi-target Stool DNA (MT- S-DNA), colonoscopy, double-contrast barium enema (based on the age of the subjects and the time intervals of 2, 5 and10 years). To compare different alternatives, costs were updated to purchasing power parity (PPP) in 2017, using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for medical care and PPP conversion factor. The ICER was the primary outcome measure in this systematic review, for comparing the screening and no-screening methods, and then in comparison with other screening techniques. The ICERs calculated as either cost per life-year gained or cost per QALY.

In this systematic review, the threshold is defined as a standard threshold in the country of origin where the paper was published, while for the countries that did not report any threshold, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended guideline was used.18–20 The criterion for assessing the cost-effectiveness was based on the recommended WHO threshold for cost-effectiveness analysis. According to this criterion, if the value of an ICER for a given intervention falls below the specified value of three-time the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, then it is considered as a cost-effective strategy.

We used the Drummond 10-point checklist, which is a standard procedure for the quality assessment of economic evaluation studies, for qualitative assessment of studies, in order to confirm their methodological quality.21 All questions had three options for the answer, including “yes”, “cannot tell” and “no”, and the corresponding value for each item was 1, 0.5 and 0, respectively. The reason for choosing a 0.5 value for the “cannot tell” response was that the information about that item was not complete. For items that were not relevant, we considered score 1.

Results

Study Selection

A flow diagram, based on the PRISMA, for choosing the relevant studies has been shown in Figure 1. In primary search, we identified 1701 relevant studies, which were published after January 2012. Removing the duplicates (841 papers) resulted in 830 articles for further analysis. After examining the title and abstracts of these studies, 92 articles were identified for full-text review and additional analysis. Finally, we found eight studies from 92 fully reviewed articles, which met our criteria. In Table 1, we have introduced the characteristics of these studies. Table 1 represents the details of methods and results, such as the lists of the models, study population, time horizon, screening techniques, the perspective of the study and outcome measure for each study, sources of cost information, type of costs, currency (type and year), discount rate, side effects, approach for expressing uncertainty and important variables in the sensitivity analysis. The results show that one study reported costs per life years saved (LYS) from CRC screening,22 six reported costs per QALYs only,23–28 and two reported both costs per LYS and costs per QALY.29 All studies examined one or more of the available screening techniques, as well as a no-screening alternative. The perspectives of the analyses were societal or third-party payers.

|  |  |

Table 1 The Characteristics of the Included Studies |

|

Figure 1 The methods to identify studies based on the inclusion criteria.Note: Adapted from Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097.30 |

Cost-Effectiveness of Common Alternative Techniques of Screening vs No-Screening

The results of the present study showed that the screening for CRC led to a decrease in the deaths from CRC in adults above 50 years of age, who were at average risk for CRC. The results demonstrated that screening by any technique was cost-effective. For one study, the cost of screening techniques ($PPP 2028 per person to $PPP 2428 per person) was less than the cost of no-screening ($PPP 3580 per person).23 In the remaining of the studies, the costs of no-screening were between $PPP 240 per person and $PPP 8422 per person, and for the alternative screening techniques, the costs were exceeding these ranges. In this systematic review, all the studies revealed that any type of screening strategies is more effective than the no-screening technique. The minimum ICER calculated in $PPP was −16265/QALY (the negative ICERs were between $PPP −16265/QALY to $PPP –1988/QALY, whereas the positive ICERs were between $PPP 1257/QALY to $PPP 55987/QALY).23 Table 2 shows the details of extracted data for alternative techniques, in comparison to the no-screening strategy.

|  |  |

Table 2 The Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratios of Different Techniques for CRC, in Contrast to the No-Screening Method |

Overall, from the studies that examining only one method of screening, in four studies, the FIT was more effective and less costly than the no-screening strategy. The FIT every 2-year and FIT yearly screening techniques were more effective and less costly than the no-screening, among all techniques.

Studies also assessed the mixed method screening and found that annual FIT/COLOx1 (colonoscopy once) and FIT/sigmoidoscopy were more effective and less costly than the no-screening method (FIT/COLOx1 and FIT/sigmoidoscopy, gained 0.11 and 0.112 QALYs per person, and saved $PPP 1396 and 1371 per person, respectively).23

In two studies, sigmoidoscopy was dominant, compared to the no-screening technique.23–25 In fact, sigmoidoscopy once and sigmoidoscopy every 5 years were less costly and more effective than the no-screening method. Single sigmoidoscopy had an ICER below $28,000/QALY, indicating the dominance of this technique to no-screening technique, in the given context-specific threshold.27

Colonoscopy every 10-year, beginning at either 50 or 70 years of age, for both sexes also dominated the no-screening.29 Only one out of seven studies showed that performing colonoscopy every 10-year was more effective and less costly than no-screening.23 Actually, this technique had an ICER lower than other techniques. In addition, only one out of seven studies reported a single colonoscopy technique. We found that the single colonoscopy was cost-effective, in comparison to the no-screening strategy, according to the given threshold.27 The studies that reported the cost-effectiveness analysis for the newer technologies of stool DNA and virtual colonography every 5-year, revealed that both techniques were cost-effective, in comparison to the no-screening strategy.24,27,28

Comparison of Different Screening Techniques

We identified eight studies, examined multiple screening methods (FOBT, FIT, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and the combination of S-DNA test, FIT and sigmoidoscopy) and reached diverse conclusions about their ICER. In three studies, annual/biennial FIT was compared to annual/biennial FOBT, showing that the ICER for annual/biennial FIT in all studies was below the accepted threshold, and thus suggesting a cost-effective strategy. Also in two out of three studies, the annual FIT was more effective and less costly than annual FOBT. The analysis performed by Ladabaum et al24 showed that yearly FIT was cost-effective when it was compared to FIT performed every 2 years (see Table 3). The comparisons made between annual FIT and sigmoidoscopy every 5-year showed that annual FIT was dominant in four out of five studies. In two of those studies, annual FIT showed less cost and more effectiveness, in comparison with sigmoidoscopy every 5-year.22,25 Only in the analysis conducted by Dan and colleagues,27 the annual FIT dominated by both single sigmoidoscopy and sigmoidoscopy every 5-year or had an ICER higher than $50,000/per QALY (see Table 4). When FOBT was compared to sigmoidoscopy of every 5-year and sigmoidoscopy once, it was observed that all the studies had an ICER below $50000/per QALY. In the study of Sharaf et al25 the annual FOBT was more effective and less costly than sigmoidoscopy once (see Table 5). When sigmoidoscopy every 10-year or sigmoidoscopy every 5-year plus annual FIT was compared to FIT yearly, it was revealed that in four out of five studies the sigmoidoscopy every 10-year or sigmoidoscopy every 5-year plus annual FIT had an ICER of above $50000/per QALY and was dominated (see Table 6).25,27 Colonoscopy every 10-year in one out of five studies was cost-effective, in comparison with the FIT yearly and annual FOBT. A study by Wong et al represented that colonoscopy every 10-year was more effective and less costly than annual FOBT (see Table 7).22 Also in one out of two comparisons, colonoscopy every 10-year was dominant, compared to the sigmoidoscopy every 5-year plus annual FIT.27 However, in another study that sigmoidoscopy every 5-year plus annual FIT considered as a base technique, and was compared to colonoscopy every 10-year, we observed less cost and more effectiveness, in comparison to the colonoscopy every 10-year (see Table 8).25

|

Table 3 The Calculated Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratios When Using FIT Yearly vs FIT Every 2-Year, and FOBT Yearly |

|

Table 4 The Calculated Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratios When Using FIT Alone vs Flexible Sigmoidoscopy (FS) |

|

Table 5 The Calculated Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratios When Using FOBT Alone vs Flexible Sigmoidoscopy (FS) |

|

Table 6 The Calculated Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratios When Using FIT+ Sigmoidoscopy vs FIT |

|

Table 7 The Calculated Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratios When Using Colonoscopy vs FIT and FOBT |

|

Table 8 The Calculated Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratios When Using Colonoscopy vs FIT + Sigmoidoscopy |

When colonoscopy every 10-year was compared with S-DNA test (3-year and 5-year), colonoscopy test had an ICER below $50000/per QALY and was dominant with 100% of the certainty. Only one study showed that the virtual colonography every 5-year was less cost-effective when compared to the established technique (see Table 9).27

|

Table 9 The Calculated Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratios When Using Colonoscopy vs Stool DNA |

Discussion

There are multiple methods, policies, and interventions for screening for CRC. These methods are used in combination or alone. These mean that we have numerous strategies for the screening of CRC, and evaluating of those strategies in terms of costs and effectiveness is, to some extent, a complex task.

As the results of this systematic review demonstrated, the CRC screening by any technique is cost-effective, in comparison with the no-screening method.

Three studies reported the cost-effectiveness analysis for the S-DNA test. The results showed that the S-DNA test was cost-effective, in comparison to the no-screening. However, this technique was less cost-effective when compared with other screening techniques (namely, colonoscopy every 10-year, barium enema 5-year, sigmoidoscopy, FIT and virtual colonography every 5-year). In our systematic review, only one study reported that the virtual colonography every 5-year was cost-effective, in comparison to the no-screening method. However, the virtual colonography every 5-year was not cost-effective when it was compared to other techniques.27 Virtual colonography every 5-year is a non-invasive procedure that potentially can be ideal for subjects who avoid invasive procedures, such as colonoscopy and FS. Although this technique has advantages, such as a reduction in complications of colonoscopy (bowel perforation, major bleeding, and deaths due to perforation), more resources need to be allocated to get the same effectiveness, in comparison with the colonoscopy.

Based on our results, there was no consensus about starting and endpoint screening ages, but it seems that the age of 50 years was the most appropriate for initiation. Kingsley et al28 examined the starting and stopping ages of screening in their analysis from the age 50 until age 100 or death, but in conclusion, they did not recommend any type of screening for people above the age of 80. The prevalence and incidence rates of CRC at different ages determine which screening technique is the most cost-effective.

In this study, two out of eight studies had reported the prevalence rate of CRC at age 50, and the decrease of CRC incidence in different screening techniques had been discussed. However, there has been no examination of the prevalence rate of CRC at different ages and the choice of age-appropriate screening techniques, which have an impact on the cost-effectiveness of screening techniques.

Overall, changes in the sensitivity and specificity of screening tests will have a different effect on the cost-effectiveness of CRC screening techniques. In the current review, four out of eight studies have demonstrated that the changes in sensitivity and specificity of the screening tests have a moderate impact on ICER, and for the other studies, this impact is minimal. For instance, in the study of Dan et al27 it is shown that when the specificity and sensitivity of CRC screening tests varied from 50% to 99%, moderate impacts were observed on the cost-effectiveness of CRC screening techniques. Thereby, screening techniques may be dominated or may no longer be cost-effective.

Although most of the models used in the studies are the same (Markov model), due to the differences in cost and effectiveness of screening strategies such as time horizon, variety of techniques in different studies, differences in sensitivity and specificity rate, it is not feasible in practice to determine which strategy is the optimal technique. Dinh et al and Kingsley et al analyzed the colonoscopy but the cost of complications was not included in the model.23,28 These factors may be one of the main reasons, leading to inconsistency in the results of the different studies.

In addition, our findings showed that all studies conducted the sensitivity analysis with alternative assumptions to examine the uncertainty with parameters. Five studies used the Monte Carlo simulation to investigate the uncertainty of the model. Uncertainty among various parameters was assessed in each study by one-way, multi-way, and probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA). In 37.5% of cases with sensitivity analysis, there was no change in the results or the effect of change in parameters was not significant. For instance, in the study by Dinh et al23 changes in the variables had not had a significant effect on the ICER, when the FIT/COLOx1 was compared to FIT and COLO.

In 62.5% of the studies, it was found that changing the parameters had a significant effect on the results. A study conducted by Dan and colleagues showed that the risk of CRC and the cost of colonoscopy accompanied by uncertainty.27 When the cost of colonoscopy was less than $300 regardless of the risk of CRC, colonoscopy was the dominant technique. When the cost of colonoscopy was above the $300, the IFOBT was considered the dominant technique in lower incidence levels of CRC, whereas, for the higher incidence level, the sigmoidoscopy revealed to be more cost-effective than the other techniques.

Limitation

One limitation when evaluating the cost-effectiveness and costing is that studies take place in different countries with different contexts, prices, and costs and at different times. Therefore, these need to be considered when decision-makers interested to use the overall results or some components of the cost-effectiveness analyses for different settings and times. It is recommended that in order to compare and value the cost differences over time, it should be adjusted by the inflation rate, and across countries should be adjusted by PPP. These adjustments are apart from the adjustment required for the differences in conducting processes. The magnitude of indirect costs in cancers is outstanding, and theoretically, the sum of the direct and indirect costs is almost a reflection of the cost of opportunity lost due to cancer.

Even though indirect costs constitute a significant part of the cancer costs and it is about a societal perspective, but only few studies included these types of costs in their analyses. This leads to an underestimation of the cancer costs and heterogeneity arises when there is an intention for comparing the results. In this review, we found that there are also other heterogeneous parameters such as time horizons, perspectives, and types of the models and included states that make it difficult to compare various outcomes one by one in different contexts.

One of the less paid subjects in a cost-effectiveness analysis is the threshold level for different countries. There is a general agreement that the threshold level for each country should be context-specific, but there is a discrepancy among the methods used for the implementation of the thresholds for different health systems. Furthermore, even for the same health systems, the threshold is kept constant for quite a long time. In some countries, it might be necessary to adjust the threshold in relation to the inflation rate.

Since the feasibility and acceptability of using screening tests according to the context of the study, is one of the important factors, but it was discussed in just one out of eight studies. For example, colonoscopy is an invasive method for screening and many people do not prefer to use it in the first step. Therefore, future studies should examine the feasibility of using screening tests and consider patient preference in the selection of alternative tests.

Conclusion

Our review showed that all CRC screening techniques are cost-effective when compared with no-screening, but there is no agreement between the results of the various studies to determine the optimal technique. The newer technologies of virtual colonography and S-DNA were not cost-effective, compared with conventional techniques (FIT, sigmoidoscopy, and conventional colonoscopy). Although both techniques were less cost-effective than other techniques, S-DNA and virtual colonography are non-invasive procedures, making them a potentially ideal choice for subjects who like to avoid any invasive procedures. Finally, additional analyses are necessary to determine the optimal technique.

To compare and utilize the results of the different studies, there should be some observations like inflation, PPP, threshold levels and the subject preference for accepting the interventions.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere thanks to all authors who responded to our communications and shared with us their original data and documents. This paper was extracted from the master’s thesis of FK, supervised by MY and supported by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Approval ID: IR.TBZMED.REC.1396.936)

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi:10.3322/caac.21492

2. Vekic B, Dragojevic-Simic V, Jakovljevic M, et al. A correlation study of the colorectal cancer statistics and economic indicators in selected Balkan countries. Front Public Health. 2020;8:29. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00029

3. Albreht T, Conroy F, Dalmas M, et al. European Guide for Quality National Cancer Control Programmes. Ljubljana, Slovenia: National Institute of Public Health; 2015.

4. European Council. Council recommendation of 2 December 2003 on cancer screening (2003/878/EC). Off J Eur Union. 2003;327.

5. Keshvari-Shad F, Hajebrahimi S, Laguna Pes M, et al. A systematic review of screening tests for chronic kidney disease: an accuracy analysis. Galen Medical J. 2020;9:e1573. doi:10.31661/gmj.v9i0.1573

6. Schoenfeld P. Quality in colorectal cancer screening with colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2020;30(3):541–551. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2020.02.014

7. Ouyang DL, Getzenberg RH, Schoen RE. Noninvasive testing for colorectal cancer: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(6):1393–1403. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41427.x

8. Redwood D, Asay E, Roberts D, et al. Comparison of fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer screening in an Alaska Native population with high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection, 2008–2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11. doi:10.5888/pcd11.130281

9. Imperiale TF, Itzkowitz SH, Levin TR, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1287–1297. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1311194

10. Administration USFaD. FDA approves first non-invasive DNA screening test for colorectal cancer. 2014. Available from: http://wwwfdagov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm409021htm.

11. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

12. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions [Internet]. 2018. Available from: http://handbook–5–1.cochrane.org/webcite.

13. International prospective register of systematic reviews. 11 February 2018. ID:CRD42018081676V. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/.

14. Smith H, Varshoei P, Boushey R, Kuziemsky C. Use of simulation modeling to inform decision making for health care systems and policy in colorectal cancer screening: protocol for a systematic review. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(5):e16103–e16103. doi:10.2196/16103

15. Heydari M, Yousefi M, Derakhshani N, Khodayari-Zarnaq R. Factors affecting the satisfaction of medical tourists: a systematic review. Health Scope. 2019;8(3):e80359. doi:10.5812/jhealthscope.80359

16. Pignone M, Saha S, Hoerger T, Mandelblatt J. Cost-effectiveness analyses of colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:96–104.

17. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines). CNS Cancer Ver. 2011;2:19–21.

18. Table W. Threshold values for intervention cost-effectiveness by region. 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/choice/costs/CER_levels/en/.

19. Ladabaum U. Cost-effectiveness of current colorectal cancer screening tests. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2020;30(3):479–497. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2020.02.005

20. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Overview of the ICER value assessment framework and update for 2017–2019. 2018.

21. Mf D. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes.

22. Wong CK, Lam CL, Wan YF, Fong DY. Cost-effectiveness simulation and analysis of colorectal cancer screening in Hong Kong Chinese population: comparison amongst colonoscopy, guaiac and immunologic fecal occult blood testing. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:705. doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1730-y

23. Dinh T, Ladabaum U, Alperin P, Caldwell C, Smith R, Levin TR. Health benefits and cost-effectiveness of a hybrid screening strategy for colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(9):1158–1166. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.013

24. Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A. Comparative effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a multitarget stool DNA test to screen for colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:427–439. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.003

25. Sharaf RN, Ladabaum U. Comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening colonoscopy vs. sigmoidoscopy and alternative strategies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:120–132. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.380

26. Sharp L, Tilson L, Whyte S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of population-based screening for colorectal cancer: a comparison of guaiac-based faecal occult blood testing, faecal immunochemical testing and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:805–816. doi:10.1038/bjc.2011.580

27. Dan YY, Chuah BY, Koh DC, Yeoh KG. Screening based on risk for colorectal cancer is the most cost-effective approach. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(3):

28. Kingsley J, Karanth S, Revere FL, Agrawal D. Cost effectiveness of screening colonoscopy depends on adequate bowel preparation rates - A modeling study. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0167452. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0167452

29. Wong MC, Ching JY, Chan VC, et al. Colorectal cancer screening based on age and gender: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Medicine. 2016;95(10):e2739. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002739

30. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.