Back to Journals » International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease » Volume 10 » Issue 1

Continuing to Confront COPD International Physician Survey: physician knowledge and application of COPD management guidelines in 12 countries

Authors Davis K, Landis S, Oh YM , Mannino D, Han M, van der Molen T, Aisanov Z , Menezes A , Ichinose M, Müllerová H , Hollingworth K

Received 28 June 2014

Accepted for publication 5 September 2014

Published 30 December 2014 Volume 2015:10(1) Pages 39—55

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S70162

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Russell

Kourtney J Davis,1 Sarah H Landis,2 Yeon-Mok Oh,3 David M Mannino,4 MeiLan K Han,5 Thys van der Molen,6 Zaurbek Aisanov,7 Ana M Menezes,8 Masakazu Ichinose,9 Hana Muellerova1

1Worldwide Epidemiology, GlaxoSmithKline, Wavre, Belgium; 2Worldwide Epidemiology, GlaxoSmithKline, Uxbridge, UK; 3University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea; 4University of Kentucky College of Public Health, Lexington, KY, USA; 5Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; 6University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands; 7Pulmonology Research Institute, Moscow, Russia; 8Federal University of Pelotas, Pelotas, Brazil; 9Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Sendai, Japan

Aim: Utilizing data from the Continuing to Confront COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) International Physician Survey, this study aimed to describe physicians’ knowledge and application of the GOLD (Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD diagnosis and treatment recommendations and compare performance between primary care physicians (PCPs) and respiratory specialists.

Materials and methods: Physicians from 12 countries were sampled from in-country professional databases; 1,307 physicians (PCP to respiratory specialist ratio three to one) who regularly consult with COPD, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis patients were interviewed online, by telephone or face to face. Physicians were questioned about COPD risk factors, prognosis, diagnosis, and treatment, including knowledge and application of the GOLD global strategy using patient scenarios.

Results: Physicians reported using spirometry routinely (PCPs 82%, respiratory specialists 100%; P<0.001) to diagnose COPD and frequently included validated patient-reported outcome measures (PCPs 67%, respiratory specialists 81%; P<0.001). Respiratory specialists were more likely than PCPs to report awareness of the GOLD global strategy (93% versus 58%, P<0.001); however, when presented with patient scenarios, they did not always perform better than PCPs with regard to recommending GOLD-concordant treatment options. The proportion of PCPs and respiratory specialists providing first- or second-choice treatment options concordant with GOLD strategy for a GOLD B-type patient was 38% versus 67%, respectively. For GOLD C and D-type patients, the concordant proportions for PCPs and respiratory specialists were 40% versus 38%, and 57% versus 58%, respectively.

Conclusion: This survey of physicians in 12 countries practicing in the primary care and respiratory specialty settings showed high awareness of COPD-management guidelines. Frequent use of guideline-recommended COPD diagnostic practices was reported; however, gaps in the application of COPD-treatment recommendations were observed, warranting further evaluation to understand potential barriers to adopt guideline recommendations.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, physician beliefs, adherence to guidelines

Introduction

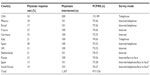

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic inflammatory lung disease that is complex and progressive, but which is also considered preventable and treatable.1 The multicomponent nature of COPD is now reflected in several regional and international management guidelines2,3 and the recently released Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD released by GOLD (Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease).1 The GOLD global strategy outlines preferred diagnosis methods for COPD, including evaluation of signs/symptoms, assessment of patient history and past exposure to risk factors, and postbronchodilator spirometric confirmation. Once a COPD diagnosis is confirmed, the GOLD global strategy also recommends a new disease-classification approach that combines symptoms (modified Medical Research Council [mMRC] dyspnea grade or COPD Assessment Test) and exacerbation risk (airflow limitation and/or history of exacerbations) to categorize patients into four groups from A (low risk, fewer symptoms) to D (high risk, more symptoms). Pharmacological treatment recommendations for disease management are provided for these groups, ranging from a short-acting anticholinergic and/or short-acting β2-agonist for group A patients to combined therapy with an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) or long-acting anticholinergic (long-acting muscarinic antagonist [LAMA]) for groups C and D (with the possibility of triple therapy with LAMA + ICS/LABA for group D) (Table 1).

| Table 1 Initial pharmacological management of COPD* |

Despite the availability of international disease-management guidelines, including those specifically aimed at primary care, COPD often remains underdiagnosed and inappropriately treated.4–7 A large web-based survey in 2011 of primary care physicians (PCPs) across the regions of Asia Pacific, Africa, Eastern Europe, and Latin America showed limited knowledge of COPD guidelines, including underutilization of spirometry for diagnosis of COPD and a general lack of awareness about the significance of exacerbations as an important factor in the management of COPD.8 Country-specific surveys largely conducted in primary care in Western Europe,5,6,9–11 Japan,12 Mexico,13 and the USA14–16 have also shown that despite knowledge of guidelines, there is a lack of adherence to guideline recommendations for the treatment of COPD. In the USA, the main barriers to guideline implementation have been reported as low familiarity, low ability or confidence in interpreting recommendations, time constraints, and low outcome expectancy among physicians.15,16

The Continuing to Confront COPD International Physician Survey aimed to describe physician beliefs and behaviors related to COPD risk factors, prognosis, diagnosis, and treatment in a broad sample of PCPs and respiratory specialists across 12 countries worldwide. The objective of this analysis was to describe physicians’ knowledge and application of the GOLD global strategy (2011 version) diagnosis and treatment recommendations and compare performance between PCPs and respiratory specialists.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

The Continuing to Confront COPD International Physician Survey was a survey of PCPs and respiratory specialists in 12 countries (Brazil, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, Russia, South Korea, Spain, the UK, and the USA) conducted between January and May 2013. Physicians were required to consult with five or more patients with COPD, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis per month, on average.

The sample of physicians was drawn from in-country databases of professional associations (eg, American Medical Association) and registries with the aim of having a national sample of PCPs and respiratory specialists at a ratio of three to one. This ratio was determined a priority in order to ensure an adequate sample size of each physician type within each country, and was not intended to represent the ratio of these physicians types practicing, or treating patients with COPD in an individual country. Each sample was proportionate to the subnational regions in each country, with the exception of Russia, where the sample was drawn to be roughly representative of the general population of the 12 most developed and populous cities.

Data collection

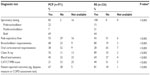

A standardized questionnaire was used in all countries to assess physician knowledge of COPD-management guidelines, diagnosis and treatment practices for COPD, and beliefs about COPD risk, natural history, and treatment effectiveness. The standardized questionnaire was translated into local languages in-country and reviewed by an independent translator and a local GlaxoSmithKline clinical advisor for accuracy and cultural relevance. The surveys were conducted online, by telephone, or face to face according to cultural preferences in each country, and were approximately 20 minutes in duration. Where possible, more than one mode of survey methodology was offered to accommodate the preferences of the physicians and to minimize the rate of refusal (Table 2). Modest payments to physicians for their time completing the survey were permitted in line with country regulations. For quality-control purposes, a minimum of 10% of interviews (all sampling methods) were validated by recontact or review of recorded interviews.

The sampling and screening process identified 1,307 physicians who agreed to be interviewed, comprising 200 physicians from the USA and approximately 100 each in the remaining countries (Table 2). The response rate by country ranged from 10% (USA) to 38% (Spain). No association was observed between poor response rates and type of interview technique used (telephone/internet/face to face); countries with the lowest response rates had the highest rates of “noncontact” issues (data not shown). For the total study population, the proportion of PCPs and respiratory specialists was 74% and 26%, respectively. The sample size of 1,307 physicians allowed for a sample precision of ±3.1% for population responses or proportions around 50%.

Outcome definitions

The primary objective of the present analysis was to describe physicians’ knowledge and application of the GOLD global strategy diagnosis and treatment recommendations and compare performance in applying these guidelines between PCPs and respiratory specialists.

To evaluate physician knowledge about COPD-management guidelines, respondents were queried about whether they were aware of any local/countrywide COPD guidelines, and if so, to what degree these guidelines influenced their everyday treatment practice. Respondents were similarly queried about the GOLD global strategy recommendations and its influence on their practice.

Physician-diagnosis practices were assessed by presenting respondents with a predefined list of diagnostic tests and instructing them to indicate which test(s) they normally conduct in order to establish a diagnosis of COPD (physicians could answer “Yes”, “No”, or “Test not available” for each test). Respondents were also asked to name the three most important factors in a patient’s history when establishing a diagnosis of COPD.

Lastly, physician concordance with prescribing a GOLD global strategy-recommended treatment for different types of COPD patients was evaluated using patient case scenarios (see Table S1 for scenario descriptions). Each patient vignette was emblematic of a typical GOLD B, C, or D patient (respondents were not told the patients’ GOLD classification as part of the descriptive text). After the scenario was read to the respondents (or displayed online), they were asked to consider which medication(s) they would typically prescribe to such a patient. Respondents could pick one or more of the medication options from a prespecified list that included: 1) short-acting bronchodilator, 2) LAMA, 3) LABA, 4) ICS/LABA combination inhaler, 5) theophylline, 6) roflumilast, 7) triple therapy (LAMA + LABA/ICS fixed-dose combination in two inhaler devices), or 8) oral corticosteroids (chronic use). Respondents could also specify other medications not included in the predefined list; these were reviewed, and those that matched one of the eight prespecified classes of drugs were recoded prior to data analysis. “Concordance” with GOLD strategy for this analysis was defined as selecting a GOLD global strategy first- or second-choice treatment option for the specific type of patient, regardless of whether a medication from the alternative choice was also selected (Tables 1 and S1). Respondents could select multiple first- (or second)-choice options and still be considered concordant. The second-choice option “LAMA and LABA” (for GOLD B, C, or D) was not evaluated, because this combination was not included in the prespecified list (no LAMA/LABA fixed-dose combination products were commercially available at the time of survey development). Given the prespecified response categories, we could not ascertain if a physician who selected both 1) LABA and 2) LAMA intended for the products to be used concomitantly or separately. For similar reasons, we did not evaluate the second-choice option of “LAMA and ICS” (for GOLD D). For the GOLD D patient scenario, if a respondent selected either LABA/ICS or LAMA and also selected roflumilast, we assumed that the physician intended to use these in combination, consistent with the indication for roflumilast for use as an add-on therapy to bronchodilator treatment.17 Respondents were considered “discordant” with GOLD strategy if they 1) selected neither a first- nor second-choice option, 2) selected a first- or second-choice option(s) along with additional nonrecommended therapies, or 3) selected a medication from the alternative choice alone.

Statistical analysis

In order to evaluate the hypothesis that PCPs and respiratory specialists vary with regard to key outcomes (utilization of GOLD global strategy-recommended diagnostic tests and guideline-concordant behavior), all countries were combined to obtain a sufficient sample size. While there was some heterogeneity observed across countries, the direction of association was similar (see Supplementary materials for country-specific data). These physician sample data are not weighted because standardized and reliable estimates of the key demographic parameters of the universe of physicians in each country were not readily available. Multivariate logistic regression models, built for each outcome separately, considered physician type as the main exposure and included potential confounding variables. While several potential confounders were considered (knowledge and influence of local/professional guidelines, knowledge and influence of GOLD global strategy, sex, year since graduated medical school, and participation in COPD-based continuing education courses), only awareness of the GOLD global strategy was significantly associated with each outcome and with physician type in univariate analyses. Therefore, all models were adjusted for awareness of the GOLD global strategy and country, and the statistical tests reported herein represent the P-value of the physician-type β-coefficient from this final adjusted model.

Results

Demographics of physician sample

In the global sample from 12 countries, approximately three-quarters of the physicians were male and about half graduated from medical school after 1990, with a similar pattern observed for PCPs and respiratory specialists (Table 3). The proportion of physicians in a multispecialty practice was slightly higher for PCPs (56%) compared with respiratory specialists (48%). Respiratory specialists were more likely to be practicing in urban/city areas (55% versus 37% of PCPs) and to report that they treated COPD patients in an inpatient or hospital-based clinic (33% versus 14% of PCPs). Respiratory specialists had a higher case mix of COPD patients (59% reported at least a third of all patients they treat regularly have COPD versus 8% of PCPs). The majority of physicians had received some continuing education on COPD (88% of respiratory specialists, 71% of PCPs), and most reported using the term “COPD” when discussing the diagnosis with their patients.

Across countries, the proportion of male physicians was greater in Japan and South Korea and lower in Russia compared with the total population; Russia had very few single-specialty practices, and fewer physicians in Japan reported that they received some continuing education on COPD (19% of PCPs; 43% of respiratory specialists). The type, setting, and location of practices showed some variation across countries (Table 3).

Knowledge of guidelines

Across all countries, a high awareness of any professional guidelines for COPD diagnosis/management, including local guidelines, was reported for both PCPs (85%) and respiratory specialists (97%) (P<0.001, Figure 1A). Results were generally consistent across countries, with the exception of France, where less than half of PCPs reported familiarity with any guidelines. The majority of physicians disclosed that professional guidelines informed their practice (88% of PCPs, 91% of respiratory specialists). Among those who stated that guidelines did not inform their practice (n=123 [11%]), the reasons most frequently given were: “I prefer to use my clinical experience” (n=41), “Guidelines do not allow for tailoring treatment to different patient circumstances” (n=35), “Guideline-suggested choice is not available” (n=31), “Guideline is not relevant/disagree with them” (n=27), and “Patient does not prefer/will not adhere to guideline-suggested choice” (n=18).

Respiratory specialists were statistically significantly more likely to report awareness of the GOLD global strategy (58% of PCPs versus 93% of respiratory specialists, P<0.001, Figure 1B); some variability across countries was observed. Despite lower awareness of the GOLD global strategy, PCPs were more likely to report they had made changes to their management of COPD patients based on these guidelines (61% of PCPs versus 51% of respiratory specialists). Among all physicians who reported that they had made changes to their management as a result of the GOLD global strategy (n=500 [57%]), changes included “Using different therapies than those previously used” (59%), “Incorporating lung function measurements” (25%) and “Incorporating the use of the COPD Assessment Test patient-reported outcome instrument” (20%).

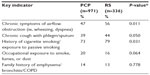

Establishing a COPD diagnosis

Both PCPs and respiratory specialists reported frequently using spirometry testing to establish a COPD diagnosis (100% of respiratory specialists indicated they use spirometry versus 82% of PCPs [P<0.001]) (Table 4). An average of 16% of PCPs reported that spirometry was not available in their practice, ranging from 0 to 5% (Russia, UK, Spain, Netherlands, Germany, Brazil) to 46% in France and 82% in Italy (Table S2). Despite the GOLD global strategy recommendation that postbronchodilator spirometry is required for diagnosis and assessment of COPD severity, 22% and 15% of PCPs and respiratory specialists, respectively, indicated that they only use prebronchodilator spirometry. Patient-reported outcomes (eg, dyspnea measure or COPD Assessment Test) were used frequently by both PCPs (67%) and respiratory specialists (81%) as part of assessing COPD. Significantly greater proportions of respiratory specialists than PCPs reported the use of chest X-ray, blood tests/oximetry, bronchodilator responsiveness, computerized tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scans, and patient-reported outcome instruments. Diagnostic practices varied somewhat by country (Table S2).

In response to an open-ended question asking physicians to state up to three top patient factors they consider when establishing a COPD diagnosis, the most frequently reported indicators, as referenced in the GOLD global strategy, were “History of smoking/exposure to passive smoking” (PCPs 73%, respiratory specialists 79%, P=0.031), and “Chronic symptoms of airflow obstruction” (PCPs 47%, respiratory specialists 56%, P=0.011) (Table 5). This pattern was generally consistent across countries, with the exception of Russia, where “Chronic symptoms of airflow obstruction” followed by “Chronic cough with phlegm” were most frequently reported, and Mexico and Germany, where “History of smoking/exposure to passive smoking” followed by “Occupational exposure to smoke/fumes/dust” were most frequently reported (Table S3).

Application of GOLD global strategy management guidelines using patient scenarios

For the GOLD category B patient scenario, only one in three PCPs (38%) provided a response that was concordant with treatment recommendations, with respiratory specialists statistically significantly more likely to provide a concordant answer (67%, P<0.001, Figure 2). The most commonly selected concordant option among both types of physicians was LAMA (PCP 22%, respiratory specialists 39%). PCPs were far more likely to report a discordant option of either an ICS-containing regimen or alternative option (short-acting bronchodilator or theophylline alone) than respiratory specialists. Across countries, a similar pattern was observed, with the exceptions of Germany, Italy, and Japan, where the concordance was similar for PCPs and respiratory specialists (Table S4).

In contrast to the GOLD category B patient, PCPs and respiratory specialists performed similarly (40% and 38%, respectively; P=0.181) for the GOLD category C patient scenario (Figure 3). PCPs indicated that they would most likely prescribe ICS/LABA combination inhalers alone (16%), while respiratory specialists commonly selected LAMA alone (13%). The most commonly mentioned discordant option reported by both physician types was triple therapy, which is only recommended for the more severe GOLD D-type patient (PCPs 16%, respiratory specialists 23%). Country-specific data were consistent with the main findings, other than in Spain, Germany, and Japan, where PCPs demonstrated higher levels of concordance versus respiratory specialists, and in Russia respiratory specialists were substantially more concordant than PCPs (Table S4).

For the GOLD category D patient scenario, both physician types performed similarly, with slightly over half providing a concordant response (P=0.513, Figure 4). The most commonly selected concordant option was triple therapy (27% of PCPs and 33% of respiratory specialists); ICS/LABA was also commonly selected. Discordant answers commonly included triple therapy in combinations not recommended by GOLD, including oral corticosteroids (PCPs 7%) and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors (respiratory specialists 10%). Countries that were not consistent with the overall pattern of concordance were the USA and Russia (less than 50% of PCPs and respiratory specialists were concordant) and Brazil and Germany (less than 50% of respiratory specialists were concordant) (Table S4).

Discussion

The Continuing to Confront COPD International Physician Survey aimed to describe PCPs’ and respiratory specialists’ beliefs and behaviors in relation to COPD diagnosis and treatment. Most PCPs and respiratory specialists reported that professional guidelines for COPD diagnosis/management informed their practice, which was widely reflected in the frequent self-reported use of spirometry to establish a diagnosis of COPD. However, with respect to the application of the GOLD global strategy for COPD management, a large proportion of both PCPs and respiratory specialists chose nonconcordant treatments for different patient scenarios.

In the current survey of 12 countries, 85% of PCPs and 97% of respiratory specialists reported an awareness of any professional guidelines for COPD diagnosis/management, including local guidelines, which is higher than that reported in a PCP survey in the USA, which showed that only between a third and a half are highly familiar with GOLD and/or American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines.14,15 We observed that significantly fewer PCPs (58%) were familiar with the GOLD global strategy compared with respiratory specialists (93%), similar to findings in previous surveys.8,10 This may be related to perceptions that the new GOLD categories have limited application in primary care and the previous suggestion that development of new treatment algorithms should involve the primary care community in order to fully engage their support.18

Despite the GOLD global strategy recommendation that spirometry is required to make a clinical diagnosis of COPD, barriers to using spirometry have previously been cited as a lack of access to spirometers, cost of testing/inadequate reimbursement for testing, patient reluctance to have the test, lack of familiarity with recommendation, and time constraints.15,16 The self-reported use of spirometry by physicians in the Continuing to Confront COPD International Physician Survey was 80%–100%, which is among the highest reported in similar surveys. In Aisanov et al, 10%–48% of physicians self-reported using spirometry as a COPD diagnostic tool,8 while other studies show that even when physicians agree on the importance of spirometry, the actual use is only 23%–54%.10,15 Self-reported spirometry use in our study is also higher than benchmarks of actual use captured in population-based electronic medical records and health care-claims databases in the USA and UK.19,20 In our population, only 16% of PCPs and 0 respiratory specialists reported that they did not have access to spirometry, which may in part explain the higher rate of spirometry use in our survey. However, we did observe a large variation in lack of access by country, ranging from 0 (Russia, UK) up to 46% (France) and 82% (Italy), reported by PCPs. While there are likely some true intercountry differences in the availability of spirometry, some of the variability observed may have been due to differences in understanding of the questionnaire (ie, some respondents interpreted a lack of access as no direct access to spirometry in their clinic, while others interpreted it as no direct access plus no access via a specialist).

While reported diagnostic practices appear largely to reflect guideline recommendations, application of the GOLD global strategy management guidelines was considerably lower. Despite respiratory specialists being significantly more likely to report knowledge of the GOLD global strategy, they did not perform appreciably better than PCPs in providing guideline-concordant answers, possibly suggesting that awareness does not necessarily translate into implementation, given the many variables that factor into the ultimate prescribing decision (eg, physician experience, local formulary, costs, and patient preferences). These findings are similar to those reported in a survey of PCPs and practice nurses in the UK, which showed high awareness levels of national COPD guidelines were not reflected in diagnoses or management strategies when presented with several case scenarios.9

However, these concordance findings must be interpreted within the limitations of the data available, as clinical scenarios are incomplete reflections of the complexity of physicians’ treatment decision making in the clinic, including the role of constraints faced by physicians with regard to formularies or local guidelines. For example, respiratory specialists in our survey showed a greater reluctance to change their practice or fully adopt guidelines, with many stating they prefer to rely on their clinical experience or feel that guidelines do not adequately account for individual patient symptoms or circumstances, including ability to adhere to recommended medications. Further, our definition of a “concordant response” required a detailed knowledge of both the GOLD patient-severity schema (A–D) and the paired treatment recommendation for each patient type. PCPs in our sample were more likely to report following local guidelines, many of which have yet to adopt the GOLD patient-severity schema or have incorporated different multidimensional indices to define disease severity.21 As the GOLD global strategy evolves and is further incorporated into local guidelines, it will be of interest to repeat this type of analysis to evaluate improvement in concordance among PCPs and respiratory specialists.

Another limitation of the data that may have affected the percentage reporting a concordant response was that we could not ascertain if a physician who selected the GOLD second-choice options of “LAMA and LABA” or “LAMA and ICS” intended for the products to be used together or as individual therapies. The impact of this limitation was likely to be minimal, however, as such combinations as “LABA and LAMA” were not commercially available in a single device, and concomitant prescriptions of the two medication classes were infrequent at the time of the survey.22

The inclusion of both PCPs and respiratory specialists in the Continuing to Confront COPD International Survey provides a unique opportunity to compare physician types with regard to attitudes and behaviors. However, the overall sample from each country was fairly small, making intercountry comparisons challenging statistically. Further, the representativeness of the sample within certain countries may be limited due to low response rates. Such low response rates did not appear attributable to the type of interview technique used in the survey, but were most notable in countries with the greatest issues relating to physician “contact”, and this, together with incentivizing respondents with a modest financial reward, may have introduced some responder bias. However, low physician response rates and varied response by country (10% in the USA to 38% in Spain) were broadly consistent with ranges previously reported in published surveys of representative physician samples,10,23,24 and may reflect the two-stage process of this survey (initial contact by post/email that invited the physician to contact the survey research organization for an appointment to complete the questionnaire at their convenience).

In summary, this global survey of PCPs and respiratory specialists showed high awareness of COPD-management guidelines. These guidelines appear to be widely followed by both PCPs and respiratory physicians with regard to diagnostic practices, including reported use of spirometry and frequent consideration of risk factors, including smoking history, symptom presentation, and family history. However, there appears to be less adoption of guidelines when applied to COPD treatment choice, with fewer physicians of both types selecting a suggested GOLD global strategy treatment choice in patient scenarios. Further research is needed to better understand the barriers to implementing treatment recommendations and rationale for alternative treatment choices using a tailored approach for different medical specialties. These data can inform physician-education strategies and public health infrastructure relevant to country-specific/local guidelines with the aim to improve COPD disease management and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The survey was conducted by Abt SRBI, a global survey research firm that specializes in health surveys. The authors would like to acknowledge editorial support in the form of draft manuscript development, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, and copyediting, which was provided by Kate Hollingworth of Continuous Improvement Ltd. The authors would like to further acknowledge the analytical support provided by Joe Maskell. This support was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK).

Disclosure

This study was funded by GSK. All authors meet the International Committee for Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship. SL, KD, and HM are employees of GSK and hold GSK shares. YMO, DM, MH, TvdM, ZA, AM, and MI served on the Scientific Advisory Committee for the Continuing to Confront COPD Survey and were paid for advisory services. Scientific Advisory Committee members were not paid for authorship services.

References

Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. Bethesda (MD):GOLD; 2014. | |

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care (Partial Update). London: NICE; 2010. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg101/resources/guidance-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-pdf. Accessed November 13, 2013. | |

Bellamy D, Bouchard J, Henrichsen S, et al. International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) Guidelines: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Prim Care Respir J. 2006;15: 48–57. | |

Sobradillo-Peña V, Miravitlles M, Gabriel R, et al. Geographic variations in prevalence and underdiagnosis of COPD: results of the IBERPOC multicentre epidemiological study. Chest. 2000;118:981–989. | |

Corrado A, Rossi A. How far is real life from COPD therapy guidelines? An Italian observational study. Respir Med. 2012;106:989–997. | |

Jones RC, Dickson-Spillmann M, Mather MJ, Marks D, Shackell BS. Accuracy of diagnostic registers and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the Devon primary care audit. Respir Res. 2008;9:62. | |

Rennard S, Decramer M, Calverley PMA, et al. Impact of COPD in North America and Europe in 2000: subjects’ perspective of Confronting COPD International Survey. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:799–805. | |

Aisanov Z, Bai C, Bauerle O, et al. Primary care physician perceptions on the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in diverse regions of the world. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:271–282. | |

Halpin DM, O’Reilly JF, Connellan S, Rudolf M. Confidence and understanding among general practitioners and practice nurses in the UK about diagnosis and management of COPD. Respir Med. 2007;101:2378–2385. | |

Glaab T, Banik N, Rutschmann OT, Wencker M. National survey of guideline-compliant COPD management among pneumologists and primary care physicians. COPD. 2006;3:141–148. | |

Glaab T, Vogelmeier C, Hellmann A, Buhl R. Guideline-based survey of outpatient COPD management by pulmonary specialists in Germany. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:101–108. | |

Fukuhara S, Nishimura M, Nordyke RJ, Zaher CA, Peabody JW. Patterns of care for COPD by Japanese physicians. Respirology. 2005;10: 341–348. | |

Laniado-Laborín R, Rendón A, Alcantar-Schramm JM, Cazares-Adame R, Bauerle O. Subutilization of COPD guidelines in primary care: a pilot study. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4:172–176. | |

Yawn BP, Wollan PC. Knowledge and attitudes of family physicians coming to COPD continuing medical education. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:311–317. | |

Salinas GD, Williamson JC, Kalhan R, et al. Barriers to adherence to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease guidelines by primary care physicians. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:171–179. | |

Perez X, Wisnivesky JP, Lurslurchachai L, Kleinman LC, Kronish IM. Barriers to adherence to COPD guidelines among primary care providers. Respir Med. 2012;106:374–381. | |

Takeda. Daxas [summary of product characteristics]. Oranienburg, Germany: Takeda; 2010. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/001179/WC500095209.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2013. | |

Jones R, Price D, Chavannes N, et al. GOLD COPD categories are not fit for purpose in primary care. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:e17. | |

Müllerová H, Lu C, Li H, Tabberer M. Prevalence and burden of breathlessness in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease managed in primary care. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85540. | |

National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Improving Quality and Patient Experience: The State of Health Care Quality 2013. Washington: NCQA; 2013. Available from: http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/Newsroom/SOHC/2013/SOHC-web_version_report.pdf. Accessed September 16, 2014. | |

Miravitlles M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Calle M, et al. A new approach to grading and treating COPD based on clinical phenotypes: summary of the Spanish COPD guidelines (GesEPOC). Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22:117–121. | |

Wurst K, St Laurent S, Muellerova H, Davis KJ. Characteristics of patients with COPD newly prescribed a long-acting bronchodilator: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:1021–1031. | |

Barr RG, Celli BR, Martinez FJ, et al. Physician and patient perceptions in COPD: the COPD Resource Network Needs Assessment Survey. Am J Med. 2005;118(12):1415. | |

Hernandez P, Balter MS, Bourbeau J, Chan CK, Marciniuk DD, Walker SL. Canadian practice assessment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: respiratory specialist physician perception versus patient reality. Can Respir J. 2013;20(2):97–105. |

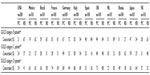

Supplementary materials

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.