Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Construction of Shame-Proneness Scale of Employee Malay People: A Study from Indonesia

Authors Cucuani H, Agustiani H, Sulastiana M, Harding D

Received 17 December 2021

Accepted for publication 30 March 2022

Published 16 April 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 927—938

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S354439

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Hijriyati Cucuani,1,3 Hendriati Agustiani,1,2 Marina Sulastiana,1 Diana Harding1

1Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia, Sumedang, West Java, Indonesia; 2Center for Psychological Innovation and Research, Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia, Sumedang, West Java, Indonesia; 3Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Islam Negeri Sultan Syarif Kasim Riau, Pekanbaru, Riau, Indonesia

Correspondence: Hijriyati Cucuani; Hendriati Agustiani, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Purpose: Culture plays a role in determining how individuals interpret their experiences. In previous studies, the experience of shame has been associated with negative behavior. However, for Malays who interpret shame more positively, the experience of shame serves to inhibit negative behavior. Therefore, shame-proneness in Malays cannot be measured as it is measured in different cultures. Two studies in this research aimed to construct a measure of shame-proneness for Malays in a work context. This measuring instrument is devoted to the work context because so many situations cause shame in everyday life. By limiting the measurement of shame for employees, the conditions that arise in the measuring instrument can be more specific.

Methods: In the first study, a qualitative study was conducted to explore the experience of shame in Malays. The second study used a quantitative method to construct a measuring instrument of shame that has good psychometric properties.

Results: The results of in-depth interviews with nine Malay employees resulted in four indicators of shame in Malay people in the work context, namely, negative self-evaluation, withdrawal, perceiving negative evaluation from others, and motivation to change the self. In the second study, 456 Malay civil servants in Pekanbaru, Indonesia, were asked to respond to a 27-item shame-proneness scale based on these four indicators. Based on the exploratory factor analysis results, the four indicators narrowed down to three factors. Confirmatory factor analysis showed that the 18-item proneness scale with three factors was the best and showed acceptable goodness of fit.

Conclusion: Shame-proneness scale of Malay employees scale was conducted in order to compose an instrument using a more comprehensive psychological approach. This has satisfactory psychometric properties and thus potentially measures the shame-proneness of Malay employees in Indonesia more accurately.

Keywords: shame-proneness, measurement, employee Malay people

Introduction

Moral emotions play an important role in encouraging moral behavior1,2 because they can direct people to behave in ways consistent with what society considers moral and appropriate.3 Shame and guilt are the best represent moral emotions because they inhibit morally inappropriate behaviour.4 Several previous studies explained that shame and guilt as moral emotions are not equivalent, where guilt motivates individuals in a positive direction, while shame makes individuals feel awry,5 escape,6 blame externally,4 and other negative impacts. Shame as a painful feeling usually accompanied by feelings of worthlessness and helplessness5 tend to make workers take counterproductive actions.7

Several other studies on shame in the workplace came up with different results. Murphy & Kiffin-Petersen8 found that shame is a discrete emotion that is considered influencing ethical behavior in the workplace because of its function in promoting interpersonal harmony and supporting social conformity and compliance with moral standards. Daniels and Robinson9 explain that shame in the context of work is something powerful, showing how a person is aware of his identity as a worker and the important standards they must meet. Failure to meet standards attached to one’s identity as a member of a profession or organization will cause embarrassment. Moreover, the negative self-evaluation after committing a moral violation that makes individuals feel ashamed positively correlates with moral identity. Therefore, people prone to shame are less likely to commit immoral acts at work like corruption.10

One of the causes of the differences in the results of shame research is cultural differences. Su11 emphasizes that culture plays an important role in determining how individuals interpret shame and guilt. Pyle12 explains that culture has a major impact on individuals in their growth, development, and learning from their environment, including how they interpret shame. Individuals from individualist cultures with independent self-construal see guilt as an internal standard that leads to adaptive consequences, while shame is seen as an external standard that leads to maladaptive consequences. However, in individuals from collectivist cultures with dependent self-construal, shame and guilt are not very different because both are associated with adaptive consequences.13 Therefore, the collectivist Asian society, including the Malay-cultured society in Indonesia, interprets shame in a more positive way.

Malay is one of the many ethnic groups in Indonesia. What is meant by Malay people are Muslims, applying Malay customs, and using the Malay language.14 Riau Province is an area with indigenous Malay culture. Thus, Malay cultural values have become the primary reference in norms and ethics in society in this area. The values developed and applied in Malay culture are rooted in Islamic religious values. In Islam, shame is considered an honorable trait that shows the level of one’s faith.15 The shame in an individual indicates that he understands religious teachings about virtues and sins and shows self-control. In Malay culture, it is explained that the presence of shame will protect one’s self from bad qualities, be careful in behavior and maintain the dignity of oneself and others.16 Therefore, research on shame proneness in Malays is a critical issue.

Although still a few, some researchers have tried to dig into the shame of Malay people. Fessler17 demonstrated in his cross-cultural research that the Malay people in Bengkulu, Indonesia (representing a collective culture) use the term shame more often than other emotions than Californians (representing an individualist culture) do. Collins and Bahar18 research on shame in Malay cultured people in Indonesia found two interpretations of shame. One of these interpretations supports Islamic morality that distinguishes haram (forbidden) and halal (permitted) practices. The other makes shame it self as the basis for a moral conscience that instills concern for others and eliminates egoism. Therefore, shame plays a role in overcoming the loss of morality in Indonesian society during a moral crisis. At least from these two studies, it is known that shame is an emotion often felt by Malays and explained as an emotion that tends to be positive. Therefore, to explore shame in Malay people, it is impossible to use concepts and measurements as is generally used so far.

Most shame studies use the Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA) measurement which also measures guilt.19 In TOSCA-3 (for adult subjects) compiled by Tangney and Dearing,2 shame is measured as a maladaptive emotion. According to Cohen et al19 shame can also lead to corrective behavior, whereas guilt can lead to withdrawal behavior. Dansie20 also conveyed the same thing, ie, TOSCA is questioned by several researchers because it failed to measure the adaptive aspect of shame or the maladaptive aspect of guilt.

Bedford and Hwang21 stated that various data show that the current conceptualization of guilt and shame (developing in American and European countries) is no longer adequate. A cross-cultural framework is needed to understand shame related to racial and cultural differences in cross-cultural studies because there is a problem in conceptualizing shame when the existing concept is applied to non-western cultures. Therefore, a shame-proneness concept for Malay people is needed to develop an appropriate measuring instrument to describe their shame-proneness more accurately.

Shame-proneness measurement for Malay employees is needed to get a description about shame-proneness on employees which can then be seen the relationship and its impact on various things in order to get the best intervention in dealing with various work behavior problems. The shame-proneness of the Malays is expected to prevent employees from taking counterproductive actions such as corruption which is currently a problem for civil servants in Pekanbaru City, Riau. Riau is one of the provinces in Indonesia that is of concern to the Corruption Eradication Commission, where civil servants are heavily involved in corruption.22 Most of the civil servants in this province are Malays. The increase in corruption among civil servants in this province may have occurred because of the erosion of shame in Malay society due to technological advances and general openness. Actions that used to cause shame are now no longer the case because more and more people are doing it, and there is no firm action from the management. Therefore, in one of these studies, Malay civil servants were used as participants. It is hoped that the shame proneness scale can later be used to explore and find solutions to these problems through this project.

The construction of the shame-proneness measurement that have previously existed in the Malay context are conducted by examining texts about shame in Malay23,24 or Muslim people, as one of the characteristics of the Malay people.25 While this research was conducted in order to compose an instrument using a more comprehensive psychological approach to measure shame in Malay employees in Indonesia more accurately. The term “employee” used in this study includes workers with various professions, including civil servants. The word “employee” in Indonesia has a different connotation from ‘civil servants.

This research consisted of two studies with different methods. By using the exploratory sequential technique of mixed method, qualitative studies are carried out at the beginning and followed by quantitative studies. Study 1 aimed to identify the indicators of shame-proneness in Malays by using a qualitative method. Study 2 used a quantitative method to construct a measuring instrument of shame that has good psychometric properties.

Study 1

Method

This study based in a thematic analysis approach aimed to explores the participant’s experience of shame at work context.26 Braun and Clarke26 suggest that Thematic analyse is a valuable and flexible method in qualitative research in psychology. The thematic analysis allows researchers to offer a rich and detailed, flexible yet complex data account through its theoretical freedom.

Participants

The participants in this study were obtained based on convenience and snowball technique. All participants were nine Malay employees judged as employees with shame proneness both in their daily life and work activities by colleagues/people who know them. Five of the nine participants are male. Five participants work in government agencies, but only four are civil servants, one is a contractor, one is an employee at a regional government-owned enterprise, and three work at private institutions. The age of the participants was in the range of 24–42 years (M = 38.67, SD = 7.14).

Procedures

Before signing the informed consent, participants were given a brief explanation of the study and data collection which was delivered orally. The informed consent contains information about the confidentiality and security of the participant’s data during the research and publication process. The participants were given several open-ended questions related to their experience of shame, including events where they experienced shame as an employee; what they felt, thought, and did when they experience shame, and; what they interpreted as shame. Semi-structured interviews were used to get an in-depth picture in a more flexible way. The interviews were conducted at the workplace in a privacy-conscious setting. To maintain the credibility of the results, the researchers conducted member checking and peer review/peer debriefing on the results of the data analysis.27 Member checking was done by asking the participants to check the accuracy of the theme drawing. Closed interviews with participants carried out this process. The next stage will only be carried out after all participants state that the overall description of the theme given is appropriate and accurately describes what they have conveyed. Later, the researcher asked an expert in the field of qualitative methods to review the drawing of the theme carried out. In addition to asking questions, peers also help improve research by accommodating criticism and input from peers.

Data Analysis

This study used a thematic analysis approach with a content analysis design that included inductive and deductive analytical methods.26 The participants’ answers regarding their feelings, thoughts, and behaviors when experiencing shame were coded based on the indicators of shame from Tangney28 as a theory driven. The process of analyzing this research data generally follows the steps of thematic analyses described by Braun and Clarke,26 namely: preparing raw data in the form of interview transcripts, reading the entire data, and coding. Qualitative data transcripts were analyzed and coded manually (low-order themes) using Microsoft word by highlighting words from respondents’ answers that match the research questions. The lower-order themes are then grouped inductively into higher-order themes. This coding process is described in a summary table containing snippets of words from the transcripts of respondents’ answers following the research questions, lower-order themes, and higher-order themes, checked by all research members. Furthermore, each theme obtained is described, interpreted and reported.

Results

Based on the results of interviews regarding events that cause the participants to experience shame, they could be categorized into the following: (1) violating the prevailing rules; (2) making mistakes at work; (3) Not being professional at work; (4) Failing to achieve/maintain performance standards; (5) Not giving the rights of others as it should; (6) Being humiliated because of a mistake made in front of others/in public. The six general causes of shame could be divided into doing inappropriate actions (breaking the rules/making mistakes) and experiencing failure.

There were four categories obtained regarding the indicators of shame, including what the participants feel, think and do when experiencing shame. Based on their experiences, the participants described the indicators of shame include: (1) negative self-evaluation (NSE); (2) withdrawal (WDR); (3) perceiving negative evaluation from others (NOE); (4) motivation to change the self (MCS).

The awareness of making mistakes or violations makes individuals judge themselves negatively, including feeling bad, incompetent, inappropriate, stupid, irresponsible, and disappointing. Such a negative self-evaluation was expressed by almost all participants, as described in the following interview excerpts:

I can’t deny … It was like … You know … It’s inappropriate … It’s … not professional. [Male, 43 years old, civil servant]

Oh, Allah, what a stupid I was … I was like …. Well, when recalling that, I think it was so bad, so very bad, too bad … I felt so sorry. [Female, 30 years old, an employee in a private institution]

Painful feelings individuals felt when experiencing a shameful event make them withdraw from the environment associated with the thing that caused that shame (leaving, avoiding the person who caused that shame and the persons who witnessed the shameful event, and the place where the shame experience occurred). Withdrawal reactions were indicated by several participants as described in the following example:

It was like, like wanting to run …. going upstairs, away from others. I felt ashamed and sad too, so I needed to be left alone for a while. [Male, 24 years old, an employee in a private institution]

Because I felt bad, so I left for a while … to calm myself down, taking a deep breath, drinking some water, then I would be more ready to face the reality. [Female, 39 years old, civil servant]

In addition, the participants also thought that other people who know the mistakes or violations they have committed would judge them negatively (although that is not necessarily the case). Although in some cases, the participants did not do the shame-causing thing intentionally or did not even think that what they did was wrong by rules for which they did not feel guilty, they felt ashamed because they were worried that other people would think negatively of them. The focus on negative evaluations of others is illustrated in the following interview excerpts:

I am a teacher, you know … It seems that the parents question how we teach their children. I think they don’t trust me. [Male, 43 years old, civil servant]

I felt ashamed because …. I think other people would think that I am an unreliable person, not reading the invitation carefully, careless … Of course, I was ashamed for not reading the invitation thoroughly. [Female, 42 years old, a regional government institution employee]

The data obtained also showed that people who experienced shame from violating the rules or failed to achieve the set standards would feel required to fix the perceived negative perceptions from other people and try to become better individuals by improving themselves or fixing the mistakes they have made. Individuals are motivated to fixing their errors and the condition so that they can cope with their shame (to be forgotten/forgiven by others), and similar incidents will not happen again, as shown in the following quotes:

To perform better in the future to make people forget that shameful incident …. Yes, I need to make a more convincing presentation, presenting better, and making sure that there are no errors. [Female, 42 years old, a regional government institution employee]

I keep trying to perform better. When I have finished something, I would ask my co-workers to check … to make corrections … even from my subordinates … (Male, 43 years old, civil servant]

Based on the participants’ descriptions of the experience of shame, what they feel when they experience shame, and what they mean by shame, we drew a general conclusion that shame is an emotion in which a person feels uncomfortable and uneasy for making a mistake or violating some ethics, rules, religious values, and social norms and failing to achieve the standards set. Individuals may still feel ashamed although no one else knows about the shameful incident, and they might feel a more intense shame if the incident is known to others. In addition, the intensity of shame and the proneness to feel ashamed decrease with the length of the work period. Over time, individuals would think that other people can accept and get used to these conditions.

Study 2

Study 2 was conducted in several stages to compile and empirically prove that The Shame-Proneness Scale for Malay Employee (SSME) constructed based on the dimensions of shame identified in Study 1 is valid and reliable.

Stage 1. Item Construction

The items were constructed based on the four indicators of shame in Malays. Each indicator consisted of eight items. The items were constructed arranged in the form of scenarios based on the experience of shame at work told by the participants in Study 1. The researcher requested five experts including doctors and doctoral students in psychology to evaluate each item. Based on the qualitative expert evaluation, several items needed to be reworded to make them easier to understand, and five items were discarded because they were judged not to be in accordance with the indicators. At this stage, 27 items on the Shame-Proneness Scale for Malay Employees resulted, consisting of seven items measuring negative self-evaluation, seven items of withdrawal, seven items of perceiving negative evaluation from others, and six items of motivation to change the self.

Stage 2. Factor Analysis

Participants

The study was carried out with 456 Malay civil servants in Pekanbaru City, Indonesia, who had worked for at least one year in their respective agencies. The participants were employees in 5 of 36 agencies under the Provincial Government in Pekanbaru City selected through cluster random sampling. Most (67.38% of 374 participants who provided information about gender) were women; their age was 39 years (SD = 9.47, from 442 participants who provided information about age) and had worked for 13.38 years (SD = 8.8, from 397 who participants who provided information about the length of work measured in years), on average.

Measurement

The Shame-Proneness Scale for Malay Employee (SSME) consisted of 27 items with four subscales (negative self-evaluation, withdrawal, perceiving negative evaluation from others, and motivation to change the self). Each item’s score ranged from 1 to 5 (1 = very-unlikely; 5 = very likely). The raw data of this study can be accessed on https://osf.io/acy75/?view_only=9bb4f35c48b548aaa639905dab2e3226.

Procedures

This research was conducted from June to July 2021. Before filling out the scale, participants were asked to read the explanation of the scale and sign the informed consent if they were willing to be involved. The participants completed the measurement anonymously to avoid bias, beginning with providing demographic information. Every participant was given a multi-purpose pouch as a souvenir to appreciate their participation in the research. This research has received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Commission of Padjadjaran University Bandung, No. 345/UN6.KEP/EC/2020.

Analysis

In the first stage, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out to identify the data structure and reduce the data.29 Principal axis factoring (PAF) was the extraction technique chosen because the multivariate normality assumption could not be met,30 and varimax rotation was used to maximize the variance within each factor. Factor analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 23, with factor extraction determined by an eigenvalue of 1.0. Eigenvalues of greater than 1.0 are considered meaningful to explain factors.30

The results of the EFA analysis showed that the KMO was 0.935, and the Bartlett test result was 4565.172 (p = 0.000). Thus, the sample is sufficiently representative of the population, and the next process could be carried out. In the initial test, based on the number of eigenvalues of more than 1.0, four factors were obtained with eigenvalues of over Kaiser’s criterion 1.0, explaining 58.79 of the total variation. There was one factor that contained items from three dimensions whose intercorrelation could not be explained theoretically. Based on this, an EFA test was carried out again by removing eight items with loading factors of less than 0.4 and items with loading factors of above 0.4 on more than one factor (cross-loading). The EFA of the 19 SSME items resulted in three factors with eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of 1.0 and a cumulative variation of 60.884%. Negative self-evaluation and perceiving negative evaluation from others were combined into factor 1 and were referred to as negative evaluation, while factors 2 and 3 were motivation to change the self and withdrawal, respectively. Table 1 shows the factor loadings of SSME items with three factors (eight items measuring negative evaluation, five items measuring withdrawal, and six items measuring motivation to change the self).

|

Table 1 Factor Loadings of the SSME’s Items Resulting from the Exploratory Factor Analysis |

In the next stage, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed on the 19 shame-proneness items. Since the data were not normally distributed the CFA was performed by estimating robust maximum likelihood (RML) using Lisrel version 8.8. The determination of the fit indices was based on the Hu and Bentler’s standard requiring that the model has at least the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value of 0.06 or lower, the comparative fit index (CFI) as well as the Tucker Lewis index (TLI) (indicated by the value of the non-normed fit index) of above 0.95, and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) of below 0.08.31

Initially, the CFA of the 19 shame proneness items showed fit indices that slightly deviated from Hu and Bentler’s standard. Based on the loading factor values, one withdrawal item (WDR3) that had the lowest value (0.5) was discarded to improve the model fit. The CFA was then repeated on the 18 shame-proneness items. Table 2 shows the fit indices of the 18 shame-proneness items with three factors and an alternative model.

|

Table 2 Fit Indices of Three-Factor Models and an Alternative Model |

It could be concluded from Table 2 that, compared to the other two models, the three-factor model with 18 items was the best. Based on the CFA for the model, each item had a t-value of greater than 1.96 and a factor loading in the range of 0.52 to 0.82 as shown in Figure 1 and more detail in the Table 3.

|

Table 3 The Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results of the SMME |

|

Figure 1 Confirmatory factor analysis of the 18 shame-proneness items (with standardized parameter estimates). |

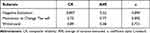

The three-factor proneness scale with 18 items had composite reliability (CR) values ranging from 0.73 to 0.89, average of variance extracted (AVE) values ranging from 0.52 to.77, and Cronbach’s alphas ranging from 0.731 to 0.894. Thus, in general, it could be said that the SSME has good reliability as shown in Table 4.

|

Table 4 Reliability of the SSME |

Discussion

Shame is an emotion that exists in every society, but cultural differences cause shame to play a different role in different societies.32 The Malays consider shame important because it acts as a social benchmark, indicating appropriateness.33 The shame individuals feel indicates that they realize that what they did was inappropriate. Therefore, shame is marked by a negative evaluation.

Negative self-evaluation occurs as an awareness that one has deviated from social values and standards. Such an awareness then becomes a reference in forming self-standard values. Individuals engaging in shameful behavior and understand the rules and values held by their society in general (including religious values and social norms) evaluate themselves negatively and perceive that other people do not like their behaviors either and thus judge them negatively. This feature distinguishes SSME from the previous shame-proneness measurement tool developed by Tangney28 because, according to Tangney, the negative evaluation only comes from the individuals themselves. In this present study, the participants perceived that negative evaluation also comes from other people who knew about the shameful incident. This finding is in line with Cook’s indicator of shame referred to as other-focused self-evaluation.34

Perceiving negative evaluation from others (NOE) is a finding of this study, where previously existing shame measurement is not described and measured. Therefore, based on the interviews in Study 1, NOE is a separate indicator. However, Gilbert34 described perceiving negative evaluation from others as a form of shame. Shame is consists of internal and external. Internal shame is an evaluation that focuses on how a person values and evaluates himself. While external shame is explained as an emotion that comes from how the self is in what other people think.

How individuals are in the eyes of others is important to people from collectivist cultures. Negative evaluations from others indicate a rejection that is felt like a punishment and means that the individuals are no longer loved. Pyle12 explains that Asian societies often used as an example of collective cultures tend to think and act by emphasizing inter-group interdependence. Based on the factor analysis, both NSE and NOE are clustered in one group, which indicates both can be drawn in a larger category. Therefore we combined negative self-evaluation and perceiving negative evaluation from others into one factor because they are both about negative evaluation; this factor was referred to as negative evaluation.

In this present study, we found the withdrawal indicator that is also suggested by Tangney.28 Although Tangney initially described that, overall, withdrawal is maladaptive, in his more recent research, shame, especially its withdrawal indicator, is seen from its more positive face. During the withdrawal process, individuals use the rest time to rethink what has happened and think about what to do next, thereby preventing future violations.35 During a withdrawal period, an individual does not just run away temporarily from what makes him feel uncomfortable until they feel calmer but there is a thought process that ultimately makes the individual understand the event, accept what has happened, forgive themselves and think about what they must then do to be re-accepted in their social environment.

Furthermore, negative evaluations and withdrawal that are felt uncomfortable make individuals try to change themselves, their ways of working, and their conditions so that they can be accepted and no longer feel the same way. Thus, individuals who have shame-proneness show motivation for self-change, which is in line with the explanation of Lickel et al36 that shame can better explain why someone has the desire to change themselves. The self at the time individuals experienced shame is different from the ideal self according to them. Such discrepancy of self causes individuals motivated to make changes to the self that they think is not as good as it should be. In addition, related to relationships, Su11 explains that the experience of shame and guilt that accompany a violation motivates individuals to try to repair damaged relationships.

Negative evaluations, withdrawals, and motivation to change the self in Malay people who experienced shame suggest the importance of social harmony in society. Collectivist culture pay more attention to relationships and emphasize social harmony than individual freedom.11 The importance of harmony makes Malay people teach their children shame from childhood.16 Children are taught to preserve their honor and that of others (especially their family and group). Aknouche and Noor37 explain that shame affects Malays in two ways: maintaining each other’s dignity and worth and the tendency to behave politely; and refraining from engaging in immoral behavior and behaviors that bring individuals to public attention. Therefore, shame for Malays is considered an indicator of awareness of norms and prevents individuals from taking actions that violate the rules/norms.

Through these three shame indicators, individuals who are more prone to shame can be distinguished from those who are not so that we can further test the impact and role of shame-proneness in the work environment. Based on the validity testing with CFA, the 3-factor SSME with 18 items model is fit. The factor loading value of each item also meets the standard and is classified as good. Based on the results, both item and factor are appropriate to measure shame-proneness. In addition, Cronbach’s alpha value that is often used to demonstrate reliability shows that the SSME has a fairly good internal consistency and so do the CR and AVE values of each factor.

Two studies have been performed to support the construction of the shame-proneness scale for Malay employees. Starting with a qualitative exploration of the content of shame in the Malay context in Study 1, it gives the results of four shame-prone factors. Some of the indicators found in this study have been found in several previous research results separately. But the results of this study confirm that Malay people’s shame is negative evaluations originating from themselves and their perceptions of other people’s evaluation. The most critical indicator is that shame also encourages self-change for the better. Furthermore, based on the explanatory factor analysis in study 2, there is a gap where only 3 factors are confirmed by combining two of the four factors proposed in study 1 in one. Negative evaluation, withdrawal, and motivation to change the self as measured by the SSME 18 items meet the validity and reliability criteria and thus can be used to measure shame in Malay people in the work context.

Shame-proneness Scale for Malay Employees is the first shame-proneness measurement instrument based on the psychological aspects and principles of preparing a psychological measuring instrument in Indonesia. This measuring instrument can be used to know the shame-proneness of Malays in a more precise work context. Once shame-proneness has been clearly described, it can be examined for its relationship to employee behaviors that are problematic in the workplace. Furthermore, cultural-based interventions can be designed to solve problems more accurately and readily accept and apply to Malay employees. These interventions can be carried out within the scope of character education, employee attitudes and behavior, work culture, management systems such as monitoring systems, giving rewards and punishments by utilizing the shame-proneness of employees, and within the scope of a more appropriate leadership style.

Limitations and Future Research

This study describes the construction and validation process of SSME tested on a sample that was not large but considered sufficient for standard psychometric property testing of the instrument. The validation was limited to confirmatory factor analysis. In the future, it will be necessary to carry out more stringent testing, including convergent and divergent validity testing and test-retest reliability testing to substantiate the empirical evidence. In addition, to improve the benefits of the SSME, it needs to be tested and developed for a wider group of Indonesian people who are known to be mostly rooted in Malay culture. Furthermore, SSME has the potential to be used to examine the relationship of shame-proneness and other psychological attributes in the workplace to improve employees’ well-being and organizational effectiveness.

Conclusions

We conducted this research to obtain a measurement of shame-proneness that takes the cultural context into account so that we hope it can measure shame-proneness more accurately specifically for workers with Malay culture. The study found that negative evaluation, withdrawal, and motivation to change the self are indicators that describe shame in Malay people. The 18-item Shame-proneness Scale for Malay Employees (SMME) based on these three indicators proved to have good psychometric properties so that it can be used to measure shame-proneness and in further research related to shame-proneness of Malay people in the work context.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

All participants gave their informed consent to be involved before they participated in this study. Informed consent included the publication of anonymized responses. All procedures performed were by the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standard. All procedures performed in this study were by ethical standards and the procedures were approved by the ethics committee of Padjadjaran University, Bandung, Indonesia.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the “5000 Doctors” scholarship program of the Ministry of Religion of the Republic of Indonesia as part of the funding for the first author’s doctoral study program at the Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia.

Disclosure

Dr Marina Sulastiana II reports a patent Measurements pending to Intellectual Property Patents & Copyrights Indonesia. The author declares no other potential conflicts of interest in this article.

References

1. Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self-control predict good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers. 2004;72(2):271–324. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x

2. Tangney JP, Dearing RL. Shame and Guilt. Salovey P, ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002.

3. Ausubel DP. Relationships between shame and guilt in the socializing process. Psychol Rev. 1955;62(5):378–390. doi:10.1037/h0042534

4. Ghorbani M, Liao Y, Cayköylü S, Chand M. Guilt, shame, and reparative behavior: the effect of psychological proximity. J Bus Ethics. 2013;114:311–323. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1350-2

5. Tangney JP, Tracy JL. Self-Conscious Emostions. In: Leary MR, Tangney JP, editors. Handbook of Self and Identity.

6. Eyre HL. The shame and guilt inventory: development of a new scenario-based measure of shame- and guilt-proneness; 2004.

7. Bauer JA, Spector PE. Discrete negative emotions and counterproductive work behavior. Hum Perform. 2015;28(4):307–331. doi:10.1080/08959285.2015.1021040

8. Murphy SA, Kiffin-Petersen S. The exposed self: a multilevel model of shame and ethical behavior. J Bus Ethics. 2017;141:657–675. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3185-8

9. Daniels MA, Robinson SL. The shame of it all: a review of shame in organizational life. J Manage. 2019;45(6):2448–2473. doi:10.1177/0149206318817604

10. Abraham J, Sari MY, Azizah A, Ispurwanto W. Guilt and shame proneness: the role of work meaning and perceived unethical of no harm no foul behavior among private sector employees. J Psychol Educ Res. 2017;25(2):90–114.

11. Su C. A cross-cultural study on the experience and self-regulation of shame and guilt. Toronto; 2010.

12. Pyle MB. Culture and regulation: examining collectivism and individualism as predictors of self-control; 2011.

13. Wong Y, Tsai J. Cultural models of shame and guilt. In: Tracy JL, Robins RW, Tangney JP, editors. The Self-Conscious Emotions: Theory and Research. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2007:209–223.

14. Suwardi MS. Dari Melayu Ke Indonesia: Peranan Kebudayaan Melayu Dalam Memperkokoh Identitas Dan Jati Diri Bangsa. Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar; 2008.

15. Al-Muqaddam MI. Fikih malu: menghiasi hidup dengan malu. Nakhlah Pustaka; 2008. Available from: http://files/1219/al-Muqaddam_2008.pdf.

16. Effendy T. Tunjuk Ajar Melayu. Pekanbaru: Dinas Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Pemerintah Propinsi Riau bekerja sama dengan Tenas Effedy Foundation; 2015.

17. Fessler DMT. Shame in two cultures: implications for evolutionary approaches. J Cogn Cult. 2004;4(2):207–262. doi:10.1163/1568537041725097

18. Collins EF, Bahar E. To know shame: malu and its uses in Malay societies. J Southeast Asian Stud. 2000;14(1):35–69.

19. Cohen TR, Wolf ST, Panter AT, Insko CA. Introducing the GASP scale: a new measure of guilt and shame proneness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;100(5):947–966. doi:10.1037/a0022641

20. Dansie EJ. An empirical investigation of the adaptive nature of shame. ProQuest Diss Theses; 2009. Available from: http://search.proquest.com/docview/305016046?accountid=17192.

21. Bedford O, Hwang K. Guilt and shame in Chinese culture: a cross-cultural framework from the perspective of morality and identity. J Theory Soc Behav. 2003;33(2):127–144. doi:10.1111/1468-5914.00210

22. Tim penyusunan Laporan Tahunan KPK 2017. Laporan tahunan 2017: demi Indonesia untuk Indonesia. Komisi pemberantasan korupsi; 2018. Available from: www.kpk.go.id/Laporan.

23. Hanifah J, Aiyuda N, Ramadhan NH, et al. Tunjuk Ajar Melayu: shame and guilt of MALAY population in Riau. In:

24. Ihsani INM, Suadana S, Muis IA, Aiyuda N, Nasution IN. Shame and guilt toward cyberloafing of Malay students in Pekanbaru, Riau. In:

25. Chairani L, Cucuani H, Priyadi S. Al-Haya’ instrument construction: shame measurement based on the Islamic concept. J Psikol Islam Dan Budaya. 2021;4(1):1–14.

26. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

27. Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mix Methods Approaches.

28. Tangney JP. Conceptual and methodological issues in the assessment of shame and guilt. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34(9):741–754.

29. Joseph F, Hair J, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate Data Analysis: Multivariate Data Analysis: Why Multivariate Data Analysis ?

30. Osborne JW, Costello AB, Kellow JT. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis. Sage; 2011. doi:10.4135/9781412995627.d8

31. Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model a Multidiscip J. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

32. Bedford OA. Culture & psychology the individual experience of guilt and shame in Chinese culture. Cult Psychol. 2004;10:29. doi:10.1177/1354067X04040929

33. Goddard C. The “Social Emotions” of Malay (Bahasa Melayu). Ethos. 1996;24(3):426–464. doi:10.1525/eth.1996.24.3.02a00020

34. Gilbert P. What is shame? Some core issues and controversies. In: Gilbert P, Andrews B, editors. Shame: Interpersonal Behavior, Psychopathology, and Culture. New York: Oxford Universiry Press; 1998:3–38.

35. Tangney JP, Stuewig J, Martinez AG. Two faces of shame. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(3):799–805. doi:10.1177/0956797613508790

36. Lickel B, Kushlev K, Savalei V, Matta S, Schmader T. Shame and the motivation to change the self. Emotion. 2014;14(6):1049–1061. doi:10.1037/a0038235

37. Aknouche N, Noor NM. The primacy of the self in shame: can shame be benevolent? Am Int J Soc Sci. 2014;3(1):59–79.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.