Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 10

Comparison of adherence and persistence among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus initiating saxagliptin or linagliptin

Authors M. Farr A , Sheehan J, Davis BM, Smith D

Received 12 May 2016

Accepted for publication 1 July 2016

Published 3 August 2016 Volume 2016:10 Pages 1471—1479

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S112598

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Amanda M Farr,1 John J Sheehan,2 Brian M Davis,1 David M Smith1

1Life Sciences, Truven Health Analytics, an IBM Company, Cambridge, MA, 2Health Economics and Outcomes Research – Diabetes, AstraZeneca, Fort Washington, PA, USA

Background: Adherence and persistence to antidiabetes medications are important to control blood glucose levels among individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D).

Objectives: The objective of this study was to compare adherence and persistence over a 12-month period between patients initiating saxagliptin and patients initiating linagliptin, two dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors.

Methods: This retrospective cohort study was conducted in MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Supplemental claims databases. Patients with T2D initiating saxagliptin or linagliptin between January 1, 2009, and June 30, 2013, were selected. Patients were required to be at least 18 years old and have 12 months of continuous enrollment prior to and following initiation. Adherence and persistence to initiated medication were measured over the 12 months after initiation using outpatient pharmacy claims. Patients were considered adherent if the proportion of days covered was ≥0.80. Patients were considered nonpersistent (or to have discontinued) if there was a gap of >60 days without initiated medication on hand. Multivariable logistic regression and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were fit to compare adherence and persistence, respectively, between the two cohorts.

Results: There were 21,599 saxagliptin initiators (mean age 55 years; 53% male) and 5,786 linagliptin initiators (mean age 57 years; 54% male) included in the study sample. Over the 12-month follow-up, 46% of saxagliptin initiators and 42% of linagliptin initiators were considered adherent and 47% of saxagliptin initiators and 51% of linagliptin initiators discontinued their initiated medication. After controlling for patient characteristics, saxagliptin initiation was associated with significantly greater odds of being adherent (adjusted odds ratio =1.212, 95% CI 1.140–1.289) and significantly lower hazards of discontinuation (adjusted hazard ratio =0.887, 95% CI 0.850–0.926) compared with linagliptin initiation.

Conclusion: Compared with patients with T2D who initiated linagliptin, patients with T2D who initiated saxagliptin had significantly better adherence and persistence.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, saxagliptin, linagliptin, adherence, discontinuation

Introduction

In the US, the incidence and prevalence of diabetes mellitus have risen dramatically.1 Using 2012 data, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 29 million individuals in the US have diabetes mellitus.2 Among individuals with diabetes mellitus, the majority have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D).3 T2D is managed with lifestyle modifications, such as diet and exercise, and with medications.4–6 Controlling diabetes mellitus by maintaining low blood glucose levels, measured with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), is important to reduce serious complications associated with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.2 Therefore, adherence and persistence to antidiabetes medications are key. Better adherence to antidiabetes medications has been associated with a number of positive clinical outcomes in addition to lowering HbA1c,7–10 including a lower risk of hospitalization and death.9 In turn, better adherence and better clinical outcomes are associated with lower health care expenditures.11–15

One medication class approved for treatment of T2D is the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i).4–6 Within the DPP-4i medication class, two medications are saxagliptin, approved in 2009,16 and linagliptin, approved in 2011.17 Although they belong to the same medication class, these medications have different active ingredients with different side effects and dosing instructions.16,17 We know of no head-to-head published studies comparing saxagliptin and linagliptin. Of the existing literature, most analyses indirectly compare saxagliptin and linagliptin using data from randomized controlled trials or adverse events reporting databases.18–22 Real-world studies are necessary to assess if medication differences affect adherence and persistence between the two drugs. Previous claims-based research comparing saxagliptin and sitagliptin initiators by Farr et al23 found that saxagliptin initiators were more adherent and more persistent to initiated DPP-4i; given the data period analyzed and the date of Food and Drug Administration approval, linagliptin was not included in that analysis. However, a recently presented analysis by Rascati et al24 found better adherence and persistence among saxagliptin initiators compared with linagliptin initiators over 12 months, although the number of linagliptin patients was small. Therefore, the objective of this analysis was to build upon the previous literature by comparing adherence and persistence over 12 months and 24 months following initiation between patients with T2D initiating saxagliptin and patients with T2D initiating linagliptin in large US administrative databases.

Methods

Data source

This retrospective cohort analysis was conducted using Truven Health MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters and Medicare Supplemental Databases. The commercial data consist of claims from self-insured employers and health plans, while the Medicare data consist of claims from individuals with Medicare supplemental insurance paid for by their former or current employers. The databases include enrollment information, inpatient and outpatient medical claims, and outpatient pharmacy claims for enrollees. Many health insurance plans of different types are included. These databases have been used to study a variety of diseases.25 Variables are created based on enrollment records and medical and pharmacy claims using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes, Current Procedural Terminology codes, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes, and National Drug Codes.

The data were previously collected and deidentified and were compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act privacy regulations. Therefore, Institutional Review Board approval and written informed consent were not sought for this study because no data collection occurred and the data used contains no identifying information.

Patient selection

Patients with at least one outpatient prescription claim with a National Drug Code for saxagliptin or linagliptin with at least a 28 days supply of medication between January 1, 2009, and June 30, 2013, were identified from the outpatient pharmacy claims with the date of the first qualifying claim defined as the index date. The drug initiated was referred to as the index drug. Patients were required to be at least 18 years old on the index date and have continuous enrollment in the 12 months prior to the index date (preperiod) and the 12 months after the index date (follow-up period). To limit the sample to new initiators, patients with a claim for a DPP-4i medication in the preperiod were excluded. Finally, patients were required to have at least one nondiagnostic medical claim with a diagnosis of T2D (ICD-9-CM 250.x0, 250.x2), whereas patients with a claim with a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM 250.x1, 250.x3) or gestational diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM 648.8x) were excluded.

Patient subgroups

The following three patient subgroups were analyzed: monotherapy patients, nonmail-order patients, and patients with 24 months of continuous enrollment following the index date. Patients were categorized as monotherapy or combination therapy initiators based on claims for other classes of antidiabetes medications around the index date. If a patient met one of the following three definitions, the patient was classified as initiating combination therapy: 1) an outpatient prescription claim in the 60 days prior to the index date and a second outpatient prescription claim in the 45 days following index for a non-DPP-4i medication; 2) an outpatient prescription claim for a non-DPP-4i drug that overlapped with index drug for at least 30 days in the first 45 days following index date; and 3) initiated fixed-dose metformin combination drug on the index date.24 Patients not meeting any of the three criteria were classified as monotherapy initiators and were evaluated in sub-analyses, as these patients have the simplest treatment regimens. The second patient subgroup comprised those who did not fill their index prescription via mail-order pharmacy. As mail-order prescriptions typically have longer days’ supply, claim-based calculations of persistence may be inflated for patients who fill their prescriptions in that way. The last subgroup of patients comprised those who had at least 24 months of continuous enrollment following the index date. For this subgroup, outcomes were measured over 12-month and 24-month follow-up periods.

Variables

The explanatory variable in this analysis was the index drug: saxagliptin or linagliptin. The outcome variables were adherence and persistence to the initiated DPP-4i for 12 months following the index date. These were also measured over the 24 months following the index date for patients with sufficient continuous enrollment. Both adherence and persistence were calculated using the service date and days’ supply fields on saxagliptin and linagliptin outpatient pharmacy claims. Adherence was defined as the proportion of days covered (PDC) over the fixed follow-up period calculated as the number of days patients had their index drug “on hand” divided by 365 days (or 730 days for the 24-month follow-up). Patients with PDC ≥0.80 were considered adherent. This is consistent with the Medicare Part D antidiabetes medication adherence quality measure for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid.26 Persistence was measured as the time from index date to the last day with the index drug on hand prior to a continuous gap of >60 days, or the end of follow-up. Patients with evidence of a gap of >60 days without their index drug were considered nonpersistent, meaning that they discontinued.

Several patient characteristics were also captured as covariates. A complete list is found in Tables 1 and 2. Demographic characteristics were measured on the index date and included age, sex, and region. Clinical characteristics were evaluated in the preperiod using diagnosis and procedure codes and included the Deyo Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)27 and evidence of macrovascular or microvascular disease. Renal impairment was defined as the presence of at least one claim with a diagnosis, a procedure, or a revenue code indicative of renal impairment, including diabetes with renal manifestations, acute renal failure, chronic kidney disease, and dialysis. Health care utilization and expenditures were also captured during the preperiod. Finally, characteristics of initiated treatment regimen were measured, including combination therapy and mail-order pharmacy use, as described earlier, and plan-level cost sharing for DPP-4i medications. The methods to derive the cost-sharing index have been previously described; briefly, the measure is the average cost-sharing value for 30-day DPP-4i prescription for the plan in which a patient is enrolled.28 All claims from patients who filled a prescription for DPP-4i but were not included in the study sample still contributed to the plan-level cost-sharing value.28 This removes variation in patient-level cost sharing, as each patient is assigned a plan-level cost-sharing value.28

Statistical analyses

Patient characteristics and outcomes were compared between the two cohorts in unadjusted analyses using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Following the descriptive analysis, multivariable models were fit to control for the following potential confounders: age, sex, presence of capitated services, payer, region, urbanicity, plan type, initiation of fixed-dose metformin combination pill on index, mail-order prescription on index, index drug regimen, preperiod total and antidiabetes prescription expenditures, cost sharing, preperiod visit to an endocrinologist or cardiologist, preperiod renal impairment, macrovascular or microvascular disease, number of unique three-digit ICD-9-CM diagnoses and Deyo CCI in the preperiod, and pregnancy during follow-up (Tables 1 and 2). These covariates were thought to impact the provider’s choice of antidiabetes medication as well as the patient’s adherence and persistence to the index drug. The odds of being adherent (PDC ≥0.80) were modeled using multivariable logistic regression, and hazards of discontinuation were modeled using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression. Additionally, adjusted Kaplan–Meier curves were generated for discontinuation. Models were run for the overall sample and in patient subgroups to test the robustness of the findings. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study sample

There were 21,599 saxagliptin initiators and 5,786 linagliptin initiators identified from January 1, 2009, through June 30, 2013, who met the study inclusion criteria. Average age was ~55–57 years old (SD 11.2–11.8), and slightly more than half of the patients were men. Significantly more saxagliptin initiators than linagliptin initiators were enrolled in a commercial insurance plan (84.0% vs 80.1%, P<0.001) (Table 1). Compared with saxagliptin initiators, linagliptin initiators had more comorbid conditions, as indicated by significantly higher proportions of patients with macrovascular (17.7% vs 22.7%, P<0.001) and microvascular disease (11.3% vs 15.4%, P<0.001). This translated into greater preperiod health care expenditures (mean $10,097 [SD $20,531] vs $14,105 [SD $31,546], P<0.001) for linagliptin initiators. Significantly more saxagliptin patients initiated their index drug as part of a fixed-dose combination with metformin (36.5% vs 14.2%, P<0.001), and therefore, fewer initiated monotherapy (29.9% vs 42.5%, P<0.001) (Table 2).

Adherence and persistence

Descriptively, a significantly higher proportion of saxagliptin patients were adherent to the index drug compared with linagliptin patients (45.9% vs 42.4%, P<0.001). The proportion of patients who discontinued their index drug during the 12-month follow-up was significantly lower for saxagliptin initiators (46.8% vs 50.9%, P<0.001) (Table 3).

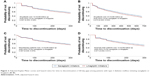

After controlling for the covariates listed in the “Statistical analyses” section, saxagliptin initiators had 21% greater odds of being adherent than linagliptin initiators (adjusted odds ratio =1.212, 95% CI 1.140, 1.289) (Figure 1). Over 12 months, saxagliptin initiators had 11% lower hazards of discontinuation than linagliptin initiators (adjusted hazards ratio =0.887, 95% CI 0.850, 0.926) (Figure 2A). Both findings were statistically significant and were similar when limited to patients initiating monotherapy (Figure 2B), or patients who did not fill their index prescription via mail-order pharmacy (Figure 2C). Findings over the 24-month follow-up period for the subset of patients with sufficient enrollment following the index date were of the same direction and magnitude (Figure 2D).

Discussion

In this claims-based analysis of patients with T2D, patients who initiated saxagliptin were more adherent and persistent to their index drug than patients who initiated linagliptin in the 12 months following initiation. These findings were consistent among patients initiating monotherapy, patients who did not fill their index prescription via mail-order pharmacy, and the subgroup of patients with 24 months of enrollment after initiation. These results indicate that although both saxagliptin and linagliptin are DPP-4is, the treatment patterns for these two medications are different in a real-world population. In both groups, adherence and persistence were suboptimal, and more research is needed to examine pathways of nonadherence and nonpersistence among adults with T2D.

Adherence and persistence with antidiabetes medications are essential for patients to experience optimal clinical outcomes, primarily glycemic control.7–10 Therefore, potential differences in adherence and persistence between antidiabetes medications using real-world data may be used to inform prescribing decisions. A similar analysis in the MarketScan claims databases by Farr et al23 found differences in adherence and persistence between patients initiating DPP-4i medications as a class compared with sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones over 12 months and 24 months following initiation. The same analysis found that within the DPP-4i initiators, patients who initiated saxagliptin had better adherence and persistence than patients who initiated sitagliptin.23 The patient sample included few linagliptin initiators, and therefore, no comparisons with linagliptin were made.23 Using more recent data from a different claims database, Rascati et al24 did compare linagliptin initiators with both saxagliptin and sitagliptin initiators over a 12-month follow-up period. The researchers identified patients with T2D in the Humana claims data who initiated a DPP-4i medication between July 1, 2011, and March 31, 2013.24 Patients insured through commercial and Medicare plans were analyzed separately.24 Adherence was measured using PDC, and patients who had a gap of ≥31 days without their initiated medication were considered nonpersistent.24 In models controlling for diabetes severity, age, and sex, linagliptin initiation was associated with lower mean PDC and higher risk of nonpersistence compared with both saxagliptin initiation and sitagliptin initiation among Medicare enrollees.24 There were no significant differences found among patients insured through commercial plans.24 However, the number of commercially insured linagliptin patients was small (218 patients).24 The results of the analysis presented here are consistent with the findings of Rascati et al that saxagliptin initiators have better adherence and persistence than linagliptin initiators. The clinical impact of these differences in adherence and persistence was not assessed in this analysis.

One possible reason for the differences noted between saxagliptin and linagliptin is dose adjustment for renal impairment. For patients with mild renal impairment, no dose adjustment is needed for saxagliptin.16 For patients with moderate to severe renal impairment, including end-stage renal disease, and those taking cytochrome P450 3A45 inhibitors, a one-step dose adjustment from 5.0 mg to 2.5 mg dose of saxagliptin is recommended.16 Saxagliptin 2.5 mg does not require dose adjustment in any situation.16 Similarly, linagliptin does not require dose adjustment among patients with renal impairment; however, for patients who are also taking a cytochrome P450 3A4 or p-glycoprotein inducer, alternative treatment is strongly recommended.17 These dosing recommendations could result in an increased adherence because saxagliptin 2.5 mg requires no adjustment and saxagliptin 5 mg can be managed with dose adjustment, but linagliptin should be discontinued entirely in some patients, which would manifest as lower adherence and persistence. Another potential explanation for differences in adherence and persistence are differences in effectiveness, although results from meta-analyses, as discussed later in this paper, are inconclusive and no head-to-head analyses have been conducted.

Several published analyses have compared outcomes other than adherence and persistence between patients treated with the two medications. An analysis by Craddy et al18 found no differences between saxagliptin and linagliptin in terms of change in HbA1c. However, using the same data but different methods, Messori et al19 found that monotherapy with linagliptin had a larger effect on HbA1c compared with placebo than monotherapy with saxagliptin, but the two drugs were therapeutically equivalent when used in combination with metformin. Esposito et al20 found that across clinical trials, the mean percentage change in HbA1c was greater for saxagliptin than linagliptin, but no statistical comparison could be made to test the significance. These three analyses relied on indirect comparisons using data from randomized controlled trials, and their inconsistent findings highlight the need for further assessments of the comparative effectiveness of these two agents using observational data or head-to-head randomized controlled trials.

The analysis presented here has limitations. First, this study was conducted using administrative claims data. Claims are originally collected for billing purposes and not for research. Therefore, miscoding or undercoding of diagnoses may occur. Second, adherence and persistence measures were based on the service dates and day supply fields on outpatient pharmacy claims. These measures assume that patients take the medication as directed. Third, clinical measures, such as HbA1c, lifestyle characteristics, such as diet and exercise, prescribing physician information, and reasons behind provider prescribing choices are not available in claims data. If there are differences in patient characteristics, which are associated with the given DPP-4i a patient was prescribed, and also associated with adherence and persistence, then the study findings may be biased by uncontrolled confounding. Also, the reasons for discontinuation are not available in claims databases. Patients may have been instructed to discontinue their medication and put on different therapies by their health care providers. The next antidiabetes medication used by patients was not captured in this analysis. Fourth, linagliptin was not on the market for the entire study period, and therefore, the sample of linagliptin patients is smaller and represents early adopters who may be different than the larger population of linagliptin users who began to use the medication in later years. Fifth, this analysis did not attempt to quantify the clinical impact of the statistically significant differences in adherence and persistence between saxagliptin and linagliptin at the patient level. This is an area for future research. At the health plan level, prior research of the Medicare diabetes medication adherence quality measure has shown that a two-percentage point increase in PDC among members with diabetes could advance the plan up to 123 positions in rank order.29 Finally, the results of this analysis may not be generalizable to patients who are uninsured or those who are insured through other types of insurance, such as Medicaid.

Conclusion

In this real-world claims-based analysis, among adults with T2D who initiated a DPP-4i medication, patients who initiated saxagliptin were more adherent and persistent to their initiated medication than patients who initiated linagliptin. Explaining the reasons for these differences, examining the potential clinical and economic impact for patients and payers, and exploring factors resulting in suboptimal adherence and persistence and interventions to improve compliance are topics for future research.

Acknowledgments

The analysis was funded by AstraZeneca. Portions of this analysis were presented at AMCP Nexus 2015, October 26–29, 2015, Orlando, FL, USA. The poster’s abstract was published in the Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, supplement volume 21, number 10-a and may be found here: http://www.amcp.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=20165.

Disclosure

JJS was an employee of AstraZeneca, which funded this analysis, at the time it was conducted. AMF, BMD, and DMS are employees of Truven Health Analytics, which received funding for this analysis. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Centers for Disease Control [webpage on the Internet]. Crude and Age-Adjusted Rates of Diagnosed Diabetes Per 100 Civilian, Non-Institutionalized Population, United States, 1980–2014. 2015. Available from: www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/prev/national/figage.htm. Accessed December 3, 2015. | ||

Centers for Disease Control [webpage on the Internet]. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. 2014. Available from: www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2016. | ||

American Diabetes Association [webpage on the Internet]. Statistics About Diabetes: Overall Numbers, Diabetes, and Prediabetes. 2014. Available from: www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/. Accessed December 3, 2015. | ||

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(suppl 1):S14–S80. | ||

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach. Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2012;55(6):1577–1596. | ||

Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden Z, Grunberger G, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology – clinical practice guidelines for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan – 2015. Endocr Pract. 2015;21: 1–87. | ||

Asche C, LaFleur J, Conner C. A review of diabetes treatment adherence and the association with clinical and economic outcomes. Clin Ther. 2011;33:74–109. | ||

Donnelly LA, Morris AD, Evans JM; DARTS/MEMO Collaboration. Adherence to insulin and its association with glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. QJM. 2007;100:345–350. | ||

Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, et al. Effect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1836–1841. | ||

Rozenfeld Y, Hunt JS, Plauschinat C, Wong KS. Oral antidiabetic medication adherence and glycemic control in managed care. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:71–75. | ||

Breitscheidel L, Stamenitis S, Dippel FW, Schoffski O. Economic impact of compliance to treatment with antidiabetes medication in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review paper. J Med Econ. 2010;13:8–15. | ||

Curkendall SM, Thomas N, Bell KF, Juneau PL, Weiss AJ. Predictors of medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:1275–1286. | ||

Roebuck MC, Liberman JN, Gemmill-Toyama M, Brennan TA. Medication adherence leads to lower health care use and costs despite increased drug spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:91–99. | ||

White TJ, Vanderplas A, Chang E, Dezii CM, Abrams GD. The costs of non-adherence to oral antihyperglycemic medication in individuals with diabetes mellitus and concomitant diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease in a managed care environment. Dis Manage Health Outcomes. 2004;12:181–188. | ||

Jha AK, Aubert RE, Yao J, Teagarden JR, Epstein RS. Greater adherence to diabetes drugs is linked to less hospital use and could save nearly $5 billion annually. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:1836–1846. | ||

AstraZeneca [webpage on the Internet]. Onglyza Prescribing Information. 2015. Available from: www.azpicentral.com/onglyza/pi_onglyza.pdf#page=1. Accessed December 3, 2015. | ||

Boehringer Ingelheim [webpage on the Internet]. Tradjenta Prescribing Information. 2015. Available from: docs.boehringer-ingelheim.com/Prescribing%20Information/PIs/Tradjenta/Tradjenta.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2015. | ||

Craddy P, Palin HJ, Johnson KI. Comparative effectiveness of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and mixed treatment comparison. Diabetes Ther. 2014;5(1):1–41. | ||

Messori A, Fadda V, Maratea D, Trippoli S, Marinai C. Testing the therapeutic equivalence of alogliptin, linagliptin, saxagliptin, sitagliptin, or vildagliptin as monotherapy or in combination with metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2014;5(1):341–344. | ||

Esposito K, Chiodini P, Maiorino MI, et al. A nomogram to estimate the HbA1c response to different DPP-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 98 trials with 24,163 patients. BMJ Open. 2015;5(2):e005892. | ||

Yang W, Cai X, Han X, Ji L. DPP-4 inhibitors and risk of infections: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(4):391–404. | ||

Nagel AK, Ahmed-Sarwar N, Werner PM, Cipriano GC, Van Manen RP, Brown JE. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor-associated pancreatic carcinoma: a review of the FAERS database. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(1):27–31. | ||

Farr AM, Sheehan JJ, Curkendall SM, Smith DM, Johnston SS, Kalsekar I. Retrospective analysis of long-term adherence to and persistence with DPP-4 inhibitors in US adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Adv Ther. 2014;31(12):1287–1305. | ||

Rascati K, Worley K, Meah Y, Everhart D. Characteristics of and medication adherence for diabetic patients receiving dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in US Medicare and commercial insurance plan. Presented at: the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Nexus, October 26–29, 2015; Orlando, FL. | ||

Truven Health Analytics [webpage on the Internet]. MarketScan Bibliography. 2014. Available from: sites.truvenhealth.com/bibliography/2014TruvenHealthMarketScanBibliography.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2015. | ||

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [webpage on the Internet]. Part C and D Performance Data. 2015. Available from: www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/PerformanceData.html. Accessed December 17, 2015. | ||

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. | ||

Gibson TB, Jing Y, Kim E, et al. Cost-sharing effects on adherence and persistence for second-generation antipsychotics in commercially insured patients. Manag Care. 2010;19(8):40–47. | ||

Farr AM, Sheehan J, Johnston SS, Kalsekar I. Simulation study of switching among diabetes medications associated with differential adherence: impact on prescription drug plan rankings for Medicare Star Ratings Measure D13-Medication Adherence for Diabetes Medications. Presented at: AMCP 2014 Nexus, October 7–10, 2014; Boston, MA. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.