Back to Journals » Clinical Ophthalmology » Volume 10

Comparison between the EX-PRESS P-50 implant and trabeculectomy in patients with open-angle glaucoma

Authors Mendoza Mendieta ME, López-Venegas A, Valdes-Casas G

Received 21 August 2015

Accepted for publication 31 October 2015

Published 4 February 2016 Volume 2016:10 Pages 269—276

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S94850

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

María Elena Mendoza-Mendieta,1 Ana Paola López-Venegas,2 Gerardo Valdés-Casas3

1Department of Anterior Segment, Dr Luis Sánchez Bulnes Hospital, Association to Prevent Blindness, Mexico City, Mexico; 2Institute of Ophthalmology, Conde de Valenciana, Mexico City, Mexico; 3Department of General Ophthalmology, Institute of Ophthalmology, Conde de Valenciana, Mexico City, Mexico

Purpose: To evaluate the EX-PRESS P-50 implant compared to standard trabeculectomy (TBC).

Methods: Single-center prospective randomized study; 20 eyes of 20 patients were treated with the EX-PRESS P-50 implant, and 20 eyes of 20 patients with TBC, over a 19-month period. Records of all patients were reviewed and compared. Success was defined as intraocular pressure (IOP) <21 and >5 mmHg or a decrease of 30% of IOP. Failure was defined as >21 mmHg or decline in visual acuity. Statistical analysis was made with Student’s t-test and χ2 test analyzed with SPSS version 13.0.

Results: The average follow-up was 8.6 months (±4.9 months) for the EX-PRESS P-50 group and 9.6 months (±5.3 months) for the TBC group. The postoperative visual acuity and IOP were not significantly different. We report more complications in the EX-PRESS P-50 group. At 3, 6, and 12 months follow-up, the control group was found to be free of complications, whereas multiple complications were observed in the EX-PRESS P-50 group at 3 and 6 months follow-up. We found no differences in either group with respect to success.

Conclusion: Both procedures are equally effective for the treatment of glaucoma, with 80% success in the EX-PRESS P-50 group and 72.7% in the control group.

Keywords: glaucoma, IOP, EX-PRESS, trabeculectomy

Introduction

Glaucoma is defined as a chronic, progressive, and irreversible neuropathy with loss of ganglion cells and nerve fibers, along with characteristic structural changes in the optic nerve.1 With an estimated 64.3 million people affected worldwide in 2013, and an expected increase to 76 million by 2020 and 111.8 million by 2040, glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness in the world and the leading cause of irreversible blindness.2

Filtering surgery is indicated when medical or laser treatments are not enough to control intraocular pressure (IOP) to prevent progression of the damage caused by glaucoma. Trabeculectomy (TBC) was introduced by Cairns in 1968 as a surgical procedure for glaucoma, and it is the procedure of choice for surgical open-angle glaucoma treatment.3

Early postoperative complications associated with this condition include hyphema, excessive filtration, wound leak, flat chamber, choroidal detachment, hypotony, suprachoroidal hemorrhage, and cataract.4,5 These complications have motivated the development of alternative techniques and devices, including the EX-PRESS® glaucoma filtration device.3,6

EX-PRESS P-50 implant

The EX-PRESS glaucoma filtration device was originally developed by Optonol Ltd. (Neve Ilan, Israel). It is an alternative procedure to TBC filtration surgery. It is made of stainless steel, is valveless, is 2–3 mm long, has a 0.4 mm external diameter and 50 μm internal diameter,7,8 is placed under a scleral flap,4 and shunts the aqueous humor from the anterior chamber to the intrascleral space and subsequently to the bulla. It is similar to TBC, but with the following benefits. The conjunctival incision is smaller, allowing the implant to be placed in eyes with previous scars, since it only needs 2-hour zones of healthy conjunctiva to properly place the device.6 The 3 mm sclerectomy made with the scleral punch in conventional TBC is replaced by the 27-gauge needle foramen that makes a self-sealing ostium, maintaining the stability of the anterior chamber during the procedure.6 The fistula has a 50 μm lumen that is more resistant to flow compared to the 750 μm of the sclerectomy in TBC. In both, the scleral sutures are flow resistant, but it is greater in the implant due to the added inherent resistance of the lumen,5 which theoretically would reduce the number of patients with flat chamber.6 With the EX-PRESS P-50 implant, it is not necessary to perform iridectomy, thus reducing the risk of bleeding, inflammation, pigment release, and vitreous collapse, thereby decreasing the number of revisions.5,7,8

The goal of this study was to compare surgical results of the EX-PRESS P-50 implant to TBC in patients with open-angle glaucoma, as well as IOP, visual capacity, and surgical complications in the short and medium term.

Methods

This study was a clinical, experimental, single-center prospective randomized study, including patients consulting at the Glaucoma Department, Institute of Ophthalmology ‘Conde de Valenciana’, with the following inclusion criteria: patients over 18 years of age with open-angle glaucoma diagnosis, intolerant to topical medications, or those who had poor compliance to topical treatment and were scheduled for surgery. The Institution’s Ethics Committee of Conde de Valenciana approved this study. After signing an informed consent form and expressing their willingness to attend the follow-up visits, these patients were enrolled in the study over a 19-month period.

Surgical treatment was indicated when it was not possible to reach the IOP goal, that is, the pressure measurements under which it is thought that there would be no progression of the disease, in spite of the maximum tolerated or recommended dose, considered as two first-line medications and one second-line medication.

Subjects with a history of eye surgery, except cataract phacoemulsification, or with a single functional eye, aphakic, with eye diseases in the last 6 months such as active blepharitis, severe dry eye, uveitis, autoimmune diseases, cicatricial conjunctivitis, and cheloid scarring, were excluded.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using a formula that adjusts sampling from finite populations,9 requiring 31 patients with 5% alpha error and 20% beta error, with a 95% confidence interval.

Forty eyes were studied, which were randomly assigned to two surgical treatment groups:

- TBC with mitomycin C.

- EX-PRESS P-50 implant with mitomycin C.

Procedure

Data were obtained from the clinical files; subsequently, a baseline evaluation of the visual capacity was performed, IOP was measured using a Goldmann tonometer (Haag-Streit AG, Könis, Switzerland) twice, and a third time if there was more than 2 mmHg difference from the two previous measurements. The eye surface and the anterior segment were examined; gonioscopy and fundoscopy were performed and increased eye pressure or open-angle glaucoma was diagnosed. Topical treatment was adjusted.

TBC surgical procedure

The surgical procedure reported by Skuta et al10 was used.

EX-PRESS P-50 implant surgical procedure

The surgical procedure reported by Sarkisian6 was used.

Postoperative follow-up

A first postoperative visit was at 24 hours, and topical antibiotic was prescribed (Ciprofloxacin), one drop four times a day; 1% prednisolone acetate, one drop six times a day; and dilator and/or cycloplegic agent, one drop two times a day. Subsequently, the patients were checked at 1 week, and first, third, sixth, and 12th postoperative month.

The following outcomes were defined:

Complete success: When the IOP was equal to or <21 mmHg but >5 mmHg or showed a 30% decrease in pressure from preoperative IOP, with no hypotensive medical treatment at 3 months follow-up.

Qualified success: IOP ≤21 mmHg or showing a 20% decrease from preoperative IOP, with hypotensive medical treatment at 3 months follow-up.

Failure: IOP >21 mmHg, or ≤5 mmHg; or less visual acuity than in the preoperative period.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used. Subsequently, bivariate analysis of the variables of interest (Student’s t-test) and nonparametric tests (χ2 test) were done. The significance for testing the hypothesis was P<0.05. The data were analyzed using the SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) statistical program.

Results

The EX-PRESS P-50 implant was placed in 20 eyes in 20 patients, and compared to a control group of 20 eyes in 20 patients who underwent TBC, excluding one patient in the TBC group who did not comply with follow-up.

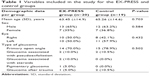

The mean follow-up was 8.6 months (standard deviation [SD] ±4.9 months) for the EX-PRESS P-50 group and 9.6 months (SD ±5.3 months) for the TBC group. The subjects from the first group, on average, were slightly younger, 63.45 years (SD ±14.9 years), than the control group, 65.2 years (SD ±14.6 years); this was not a statistically significant difference (Table 1).

| Table 1 Variables included in the study for the EX-PRESS and control groups |

There was greater prevalence in male subjects and left-eye procedures, 61.9% in males and 38.1% in females. So, a bivariate analysis was performed with the operated eye and sex of the patient as variables, and no significant differences were found (P=0.75). There was also no difference between the operated eye and the surgical procedure (P=0.621) since out of the left eyes, 47.6% were from the EX-PRESS P-50 group and 52.4% were from the TBC group.

Visual acuity per treatment group

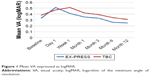

The mean of visual capacity measured in logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR), per group of treatment during the study period (1 day, 1 week, 1 month, 3, 6, and 12 months), showed on the first day a significant difference in visual acuity between the EX-PRESS P-50 and TBC groups, with P=0.049. There was no significant difference in visual capacity in subsequent controls (Figure 1 and Table 2).

| Figure 1 Mean VA expressed as logMAR. |

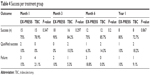

| Table 2 Visual acuity per treatment group |

Intraocular pressure

There were no significant differences in the mean IOP evaluated with Student’s t-test at the established time points (baseline, 1 day, 3, 6, and 12 months). In both groups, the IOP reduction on the first day was 0–34 mmHg and in the first week was 2–30 mmHg, with no significant differences (P=0.189 and P=0.357, respectively). In the first month, the range of pressure reductions in the control group were 5–42 and 6–30 mmHg (P=0.380) in the EX-PRESS P-50 group and control group, respectively; in the third month, the pressures were 8–22 mmHg in the control group and 5–23 mmHg (P=0.145) in the EX-PRESS P-50 group; and in the sixth month, pressures were 8–19 mmHg in the control group and 5–44 mmHg (P=0.783) in the EX-PRESS P-50 group, with no significant differences between groups. Finally, pressures were 7–19 mmHg in the control group and 9–18 mmHg in the EX-PRESS P-50 group, with no significant differences (P=0.627; Table 3 and Figure 2).

| Table 3 Mean IOP |

| Figure 2 Mean IOP. |

Surgical success

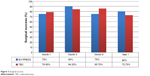

Regarding surgical success per treatment group, in the first month, 75% of subjects in the EX-PRESS P-50 group were successful, while 78.9% in the control group were successful (P=0.347); in the third month, 90% in the EX-PRESS P-50 group were successful, while 84.2% with TBC were successful (P=0.297); and in the sixth month, 75% of subjects with EX-PRESS P-50 were successful and 85.7% with TBC were successful (P=0.200). Finally, 80% were still successful with EX-PRESS P-50, while 72.7% with TBC were successful (P=0.867; Table 4 and Figure 3).

| Table 4 Success per treatment group |

| Figure 3 Surgical success. |

Surgical complications

No significant differences were found in the bivariate analysis, among the complications in both groups in the first week (P=0.247), with 45% in the EX-PRESS P-50 group and 42.1% in the TBC group. Among the complications in the EX-PRESS P-50 group, we found hypotony 15%, but no choroidal detachment, whereas in the TBC group, there was no hypotony but 10% of patients had choroidal detachment. This could be associated with the sudden changes in IOP during the surgery of patients who underwent TBC. In terms of the Seidel test and resuture, the TBC group more often had a positive Seidel test, with 26.3% versus 20.0%; however, 4.7% more subjects had resuture in the EX-PRESS P-50 group.

In the first month, there was no significant difference in complications between both groups (P=0.502), 25% in the EX-PRESS P-50 and 15.8% in the TBC group. In the first group, 5% had hypotony and 5% choroidal detachment. In contrast, the second group had no hypotony, but 10.5% of the subjects had choroidal detachment. Both groups continued with the same positive Seidel test rate. The positive Seidel test and resuture is still greater in the EX-PRESS P-50 group found in 10% of cases.

In the third month, there were no complications in the TBC group, but 5% in the EX-PRESS P-50 group required resuture. The difference was not significant between the groups (P<0.513).

Neither was there any significant difference found (P=0.405) in the sixth month. The TBC group still had no complications, and the other group presented hypotony, Seidel, resuture, and choroidal detachment. At 1-year follow-up, there were no complications in any of the groups (Table 5 and Figures 4 and 5).

| Table 5 Complications per treatment group |

| Figure 4 EX-PRESS P-50 complications. |

| Figure 5 TBC complications. |

Discussion

In terms of visual acuity, this study shows a significant reduction of vision from baseline levels of logMAR on the first day after surgery, but an improvement of vision to near baseline levels of logMAR by the first month in the EX-PRESS P-50 group, and by the third month in the TBC group. Vision continued to improve in both groups, and after the sixth month, slight improvements above baseline levels of logMAR were observed. These results are in accordance with those of Netland et al,11 who also found a reduction of visual acuity on the day following the procedure and recovery by the first month in the EX-PRESS patients and by the third month in TBC patients. Similarly, Seider et al12 noted a return to baseline levels of vision at the third month in both groups.

Likewise Good and Kahook13 reported a very fast recovery of vision in the EX-PRESS group where vision near baseline levels of logMAR were achieved 1 week postoperation. In our study, the TBC group returned to baseline vision within 1 month.

Intraocular pressure

In assessing IOP, our study found similar changes in IOP between the two groups, without significant differences at any point. The mean preoperatory IOP in the EX-PRESS P-50 was 22.95 mmHg (SD 9.22), in the trabeculectomy (TBC) group 23.79 mmHg (SD 12.46); at the final follow up visit the IOP was 13.09 mmHg (SD 3.36) in the EX-PRESS P-50 group and 13.4 mmHg (SD 3.2) in the TBC group. These results are similar to the ones reported by Maris et al,8 in which preoperative pressure was 26.2±10.5 and 25.5±9.9 mmHg. In the EX-PRESS and TBC groups, at the final follow-up visit, IOP was 13.7±6.4 and 12.9±8.5 mmHg, respectively. In addition, the mean IOP in both groups did not differ statistically from the third month to the end of their study.

Our results are consistent with previous published work about comparable success rates for each treatment group. At the last follow-up visit, the success rate of this study for EX-PRESS P-50 group was 90% (80% complete success and 10% qualified success), while the TBC success rate was 90.9% (72.7% complete success and 18.2% qualified success). Our results confirm those of Maris et al,8 who had 90% success in the EX-PRESS group and 92% in the TBC group.

Marzette and Herndon5 also documented surgical success rates of 82% for EX-PRESS and 71% for TBC, but without statistical significance (P=0.182). The lower success rates in their study compared to this study may be explained by the sample of patients that were included, among them previous failed glaucoma surgeries, which according to Mariotti et al14 is one of the principal risk factors for failure (P=0.02). Presumably the reason for the lower success within previously failed glaucoma surgeries is the increased earlier conjunctival scarring near the second filtration surgery.

Furthermore, Good and Kahook’s13 study did not find statistically significant differences in the success rates between the groups, but his study revealed slightly lower rates of success in both groups, with 82.85% success rate for EX-PRESS and 82.86% for TBC (unqualified success of 77.14% for EX-PRESS versus 74.29% for TBC [P=1.00], and qualified success of 5.71% and 8.57% [P=0.99], respectively). A plausible reason for the different rates of success might be the definition of success, considered to be an IOP of more than 5 mmHg but less than 21 mmHg.

In contrast to previous studies, de Jong et al15 declared that control of the IOP in the first year was more effective with an EX-PRESS device than with TBC (86.6% success versus 61.5%, respectively), although the definition of success used by de Jong et al was different than ours, with a threshold pressure of 15 mmHg instead of 21 mmHg. The difference in success rates between his groups was statistically significant (P=0.01).

With regard to complications, the hypotony rate was higher in the EX-PRESS group than in the control, even though the rate of hypotony of this study was within the values previously reported for EX-PRESS in the range from 4%5,8 to 47.2%.12 This reduction of hypotony rates on TBC group compared with previous studies could be explained by the use of ophthalmic viscosurgical devices during the TBC procedure. An alternative explanation for this finding includes less suture tension on the flap in the EX-PRESS group, or a looser seal of the flap against the EX-PRESS implant.

On the other hand, similar to other studies, choroidal detachment was more frequent after TBC. The rate of this complication was also in the range previously published (from 3%5 to 38%).8

Conclusion

According to the study and the results obtained, we can conclude that both procedures for open-angle glaucoma treatment are equally efficacious, since there was no significant difference in IOP control or surgical success at 1 year, which was 80% in the EX-PRESS P-50 group and 72.7% in the TBC group.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interests in this work. The authors have no commercial interest in the materials discussed.

References

Yanoff M, Duker JS. Epidemiology of glaucoma. In: Ramulu P, Friedman DS, editors. Ophthalmology. China: Elsevier; 2009:1095–1101. | ||

Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081–2090. | ||

Chan JE, Netland PA. EX-PRESS glaucoma filtration device: efficacy, safety, and predictability. Med Devices (Auckl). 2015;8:381–388. | ||

Dahan E, Carmichael TR. Implantation of a miniature glaucoma device under a scleral flap. J Glaucoma. 2005;14(2):98–102. | ||

Marzette L, Herndon LW. A comparison of the Ex-PRESS™ mini glaucoma shunt with standard trabeculectomy in the surgical treatment of glaucoma. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2011;42(6):453–459. | ||

Sarkisian SR. The ex-press mini glaucoma shunt: technique and experience. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2009;16(3):134–137. | ||

Nyska A, Glovinsky Y, Belkin M, Epstein Y. Biocompatibility of the Ex-PRESS miniature glaucoma drainage implant. J Glaucoma. 2003;12(3):275–280. | ||

Maris PJ Jr, Ishida K, Netland PA. Comparison of trabeculectomy with Ex-PRESS miniature glaucoma device implanted under scleral flap. J Glaucoma. 2007;16(1):14–19. | ||

Velazco RV, Martinez OV, Roiz HJ, et al. Cálculo del tamaño de muestra. Muestreo y Tamaño de muestra. Buenos Aires, Argentina. Editorial e-libro.net; 2003:45. | ||

Skuta GL, Beeson CC, Higginbotham EJ, et al. Intraoperative mitomycin versus postoperative 5-fluorouracil in high-risk glaucoma filtering surgery. Ophthalmology. 1992;99(3):438–444. | ||

Netland PA, Sarkisian Sr Jr, Moster MR, et al. Randomized, prospective, comparative trial of EX-PRESS glaucoma filtration device versus trabeculectomy (XVT study). Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(2):433–440. | ||

Seider MI, Rofagha S, Lin SC, Stamper RL. Resident-performed Ex-PRESS shunt implantation versus trabeculectomy. J Glaucoma. 2012;21(7):469–474. | ||

Good TJ, Kahook MY. Assessment of bleb morphologic features and postoperative outcomes after ex-press drainage device implantation versus trabeculectomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(3):507–513. | ||

Mariotti C, Dahan E, Nicolai M, Levitz L, Bouee S. Long-term outcomes and risk factors for failure with the EX-press glaucoma drainage device. Eye (Lond). 2014;28(1):1–8. | ||

de Jong L, Lafuma A, Aguadé AS, Berdeaux G. Five-year extension of a clinical trial comparing the EX-PRESS glaucoma filtration device and trabeculectomy in primary open-angle glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:527–533. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.