Back to Journals » Clinical Ophthalmology » Volume 8

Combined corneal allotransplantation and vitreoretinal surgery using an Eckardt temporary keratoprosthesis: analysis for factors determining corneal allograft survival

Authors Lee DS, Heo JW, Choi HJ, Kim MK, Wee WR, Oh JY

Received 2 January 2014

Accepted for publication 10 January 2014

Published 25 February 2014 Volume 2014:8 Pages 449—454

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S60008

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Dae Seung Lee,1 Jang Won Heo,1 Hyuk Jin Choi,2 Mee Kum Kim,1 Won Ryang Wee,1 Joo Youn Oh1

1Department of Ophthalmology, Seoul National University Hospital, 2Seoul National University Hospital Healthcare System Gangnam Center, Seoul, Korea

Purpose: To evaluate the outcome of corneal allotransplantation in combined penetrating keratoplasty and vitreoretinal surgery using a temporary keratoprosthesis, and to determine the factors affecting corneal allograft survival.

Methods: We reviewed the medical charts of eleven patients who had undergone combined corneal allotransplantation and pars plana vitrectomy using an Eckardt temporary keratoprosthesis, for the treatment of corneal opacification and vitreoretinal disease. The survival rates of the corneal grafts were assessed, and patient demographics, the diagnosis of corneal and retinal disease, the preoperative ocular characteristics, and surgical methods were compared between the group with graft survival and that with graft failure.

Results: The causes of corneal opacification were corneal laceration (four eyes), infectious keratitis (four eyes), atopic keratitis (one eye), rejected corneal graft (one eye), and uveitis-related bullous keratopathy (one eye). The preoperative diagnoses included endophthalmitis (six eyes), posterior uveitis (one eye), vitreous opacity or hemorrhage (two eyes), and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (two eyes). The survival rate of the corneal allografts was 27.3% (3/11 eyes). The mean survival time was 391 days during the mean follow-up period of 687 days. The retinal surgery was successful in 81.8% (9/11 eyes) of cases. The presence of active inflammation in the cornea at the time of surgery was significantly correlated with graft rejection (P=0.004). Other factors, including age, the presence of glaucoma, type of corneal and retinal disease, or type of retinal surgery, such as silicone oil injection and gas tamponade, had no significant correlation with graft rejection.

Conclusion: Combined corneal allotransplantation and pars plana vitrectomy using a temporary keratoprosthesis allowed for successful surgical intervention in vitreoretinal disease. However, only 27.3% of corneal allografts survived, depending on the presence of active inflammation in the cornea.

Keywords: corneal transplantation, vitrectomy, inflammation

Introduction

The combination of vitreoretinal surgery with penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) is a useful method for treating patients with vitreoretinal disorders complicated by corneal opacification. Previous studies have reported on favorable outcome of combined PKP and vitreoretinal surgery using a temporary keratoprosthesis.1−9 However, most of the studies focused on the retinal outcome after surgery, and few studies evaluated the factors positively or negatively affecting the outcome of corneal allografts, in combined corneal allotransplantation and vitreoretinal surgery.

We here investigated the survival of corneal allografts as well as the outcome of retinal surgery in patients who underwent combined corneal allotransplantation and vitreoretinal surgery using an Eckardt temporary keratoprosthesis (Heinrich Woehlk Kontaktlinsen, Kiel, Germany), for the treatment of corneal opacification and vitreoretinal disorders. In addition, we analyzed clinical, ocular, and surgical factors, to identify the factors affecting the outcome of corneal allotransplantation.

Subjects and methods

Study population and data collection

We reviewed the medical records of eleven patients who had undergone combined PKP and pars plana vitrectomy using an Eckardt temporary keratoprosthesis in our hospital between 2009 and 2012. An Institutional Review Board (IRB)/Ethics Committee approval was obtained (Seoul National University Hospital). The patients with follow- up of more than 4 months were included. The following data were collected: demographic data, including age and sex; which of the two eyes was involved; diagnosis of corneal and retinal disease; the preoperative ocular characteristics, including corneal vascularization, corneal inflammation, infection, glaucoma, or phakic status; the surgical method; the postoperative complications, such as rejection, infection, glaucoma, or phthisis; the time to graft failure; causes of graft failure; and the resolution or recurrence of retinal diseases. The survival rates of corneal allografts were assessed as the primary outcome measure. Clinical, ocular, and surgical factors were compared between patients with graft survival and those with graft failure, to identify the factors affecting the survival of corneal allografts.

Surgical procedures and postoperative care

The procedure was performed, under general anesthesia, as follows: a Flieringa ring (Storz Ophthalmics, Heidelberg, Germany) was secured to the sclera with four 6-0 black silk interrupted sutures (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA). The corneal button was excised using a 6.5 to 7.0 mm trephine (Kai industries Co, Ltd, Seki City, Japan), and the removal of either the cataract or intraocular lens, and anterior or posterior synechiolysis were done, as necessary. Next, an Eckardt temporary keratoprosthesis was inserted in the corneal window and tightly sutured onto the recipient bed to minimize leakage. Then, a standard three-port pars plana vitrectomy was performed. Depending on the status of the retina, pneumatic retinopexy (Samkwang Gas tech Co Ltd, Seoul, Korea), endophotocoagulation (Quantel Medical, Auvergne, France), transscleral cryopexy (ERBE Elektromedizin GmbH, Tuebingen, Germany), or silicone oil injection (Oxane 1300; Bausch & Lomb Inc., Rochester, NY, USA) was also performed, with the keratoprosthesis in place. After the vitreoretinal surgery, the Eckardt keratoprosthesis was removed, and donor cornea that was 0.25–1.0 mm larger than the recipient trephine was secured in place with 10-0 nylon interrupted sutures (Ethicon). After completion of the keratoplasty, intraocular gas (Samkwang Gas Tech Co, Ltd,) exchange or silicone oil injection (Oxane 1300; Bausch & Lomb Inc.), to supplement the loss of oil during the keratoplasty, was performed. When necessary, scleral fixation of intraocular lens was also performed.

Postoperatively, topical prednisolone acetate and topical antibiotics were applied four times per day (QID). Topical prednisolone acetate was applied QID for the first 12 months after the operation and tapered to two times per day thereafter. Oral prednisolone 30 mg was administered every day (QD) for the first postoperative week and tapered to 20 mg QD for the second week and 10 mg QD for the third week. Loosened sutures were immediately removed.

“Graft failure” was defined as the occurrence of epithelial or stromal edema and irreversible loss of corneal clarity under slit-lamp examination. “Graft survival time” was defined as the period from the surgery until the day when the graft failure was first noted. “Graft rejection” was defined as the sudden loss of the corneal clarity, with the presence of a rejection line or keratic precipitates on the graft.

Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analyzed using SPSS software version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method to estimate the median time to graft rejection. The logrank test was used to assess the statistical significance of the differences in the median survival time between the groups. Comparison between the groups was also performed, using the Mann–Whitney test and Fisher’s exact test. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The patient demographics and detailed profiles were summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Eight patients were male, and three patients were female. The mean age at the time of surgery was 49.0 years (range 3–75 years). The mean postoperative follow-up period was 687±309 days (range 130–1,052 days). Causes of corneal opacification included corneal laceration (four eyes), infectious keratitis (four eyes), atopic keratitis (one eye), rejected corneal graft (one eye), and uveitis-related bullous keratopathy (one eye) (Table 1). Diagnoses of vitreoretinal diseases included endophthalmitis (six eyes), posterior uveitis (one eye), retinal detachment (two eyes), and vitreous opacity or hemorrhage (two eyes) (Table 1).

The combined surgical procedures performed were (Table 2): lensectomy (five eyes), extracapsular cataract extraction (one eye), intraocular lens removal (one eye), laser photocoagulation (six eyes), silicone oil injection (six eyes), and intravitreal gas tamponade (two eyes).

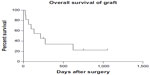

The overall survival rate of corneal allografts was 27.3% during the mean follow-up period of 687±309 days (range 130–1,052 days) (Figure 1). In total, eight out of eleven grafts underwent immune rejection. All the patients with rejection were on topical steroids QID or BID at the time that the rejection developed. After rejection, oral prednisolone was administered 30 mg QD, and topical prednisolone acetate was applied every 2 hours for 4 weeks. However, none of the cases with rejection were reversed by medication, and one eye had repeat PKP (patient 7). The median survival time to graft rejection was 391±124 days. Resolution of the vitreoretinal pathologies and retinal attachment were achieved in all eyes immediately after surgery. However, one eye required additional surgery with vitrectomy, silicone oil injection, and encircling because of the recurrence of retinal detachment 29 days after the primary surgery (patient 8). Two eyes eventually developed phthisis bulbi (patients 4 and 10). The overall success rate of vitreoretinal surgery was 81.8% (9/11 eyes). Secondary glaucoma developed in one eye (patient 3).

Regarding the visual outcome, nine eyes (81.8%) attained equal or better visual acuity at the end of follow-up compared with preoperative visual acuity: the final visual acuity improved in two eyes and remained unchanged in seven eyes. On the other hand, the visual acuity decreased in two eyes after surgery. All two eyes with poorer final visual acuity were cases with endophthalmitis (patients 4 and 8), where phthisis bulbi developed in one eye (patient 4) and corneal graft rejection developed irreversibly in one eye (patient 4).

To identify the factor(s) affecting the surgical outcome of corneal allografts, clinical and ocular characteristics, and surgical methods were compared between patients with graft survival and those with graft rejection (Tables 2 and 3). As a result, the presence of active inflammation or infection in the cornea at the time of surgery was significantly associated with the occurrence of graft rejection. Seven out of eight eyes that had active inflammation in the cornea before surgery underwent graft rejection, whereas eyes without corneal inflammation were not rejected (P=0.024) (Table 2). The mean graft survival time was 117±36 days in eyes with corneal inflammation and 909±116 days in eyes without corneal inflammation (P=0.004) (Table 3 and Figure 2A). When analyzed for patients with corneal neovascularization, the mean graft survival time was 136±38 days in eyes with corneal neovascularization and 520±171 days in eyes without corneal neovascularization, but the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.223) (Table 3 and Figure 2B). Also, regarding retinal detachment, the mean graft survival time was 261±148 days in eyes with retinal detachment and 474±121 in eyes without retinal detachment (P=0.266) (Table 3 and Figure 2C). Other factors, such as history of previous PKP or types of retinal surgery, including silicone oil injection and gas tamponade, had no significant correlation with the graft failure or with the graft survival time (Tables 2, 3 and Figure 2D−F).

| Table 3 Analysis for factors affecting the survival time of corneal allografts |

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that 27.3% of corneal grafts (3/11 eyes) survived following combined corneal allotransplantation and pars plana vitrectomy using temporary a Eckardt keratoprosthesis, and the retinal surgery was successful in 81.8% (9/11 eyes). Previous studies have reported that the survival rates of corneal grafts ranged from 65%–83% in corneal allotransplantation combined with vitrectomy, and the success rates of retinal surgeries ranged from 71%–100%.1−7 Compared with previous reports, the survival rate of corneal allografts in our patients was lower, while the outcome of retinal surgery was compatible with other studies. Also, considering that an overall survival rate of corneal allografts in the Korean population has been reported to be 80.3%,10 the corneal allograft survival rate was markedly reduced in combined allotransplantation with vitreoretinal surgeries.

When we analyzed for factors affecting corneal allograft survival, we found that the presence of active inflammation in the cornea at the time of surgery was significantly associated with the graft survival rate and time. Our study population included more severe cases of corneal and vitreoretinal disease, with seven of eleven patients having active inflammation in the cornea and six having endophthalmitis that was not controlled by medication. Hence, the high rate of active corneal inflammation in our study group may account for the low rate of corneal graft survival in our study compared with previous reports. However, considering that early surgical treatment is essential for preserving vision and the eyeball in patients with endophthalmitis or retinal detachment, the combined surgery of corneal allotransplantation and vitrectomy would be a useful and effective method for treating vitreoretinal diseases in patients with corneal opacification. This is also reflected by our observation that resolution of the vitreoretinal pathologies and retinal attachment was achieved in all eyes immediately after surgery and that the overall retinal outcome was a success in 76.9% of patients.

Of note, surgical procedures such as gas tamponade or silicone oil injection did not have a significant effect on corneal graft survival in our study. However, since gas or silicone oil might negatively affect corneal endothelium,10,11 further studies, including more patients and longer follow-up, would be necessary to identify surgical factors impacting the outcome of corneal grafts.

In summary, combined corneal allotransplantation and pars plana vitrectomy using a temporary Eckardt keratoprosthesis allowed for early and successful surgical intervention in vitreoretinal diseases in patients with coexisting corneal opacity. However, the corneal allografts survived in only 27.3% of the patients, largely depending on the preoperative status of the cornea, such as the presence of active inflammation. Hence, patients with active corneal inflammation should be informed prior to surgery and carefully followed after surgery for development of corneal graft rejection.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant of the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A111609).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Gross JG, Feldman S, Freeman WR. Combined penetrating keratoplasty and vitreoretinal surgery with the Eckardt temporary keratoprosthesis. Ophthalmic Surg. 1990;21(1):67–71. | |

Khouri AS, Vaccaro A, Zarbin MA, Chu DS. Clinical results with the use of a temporary keratoprosthesis in combined penetrating keratoplasty and vitreoretinal surgery. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010;20(5):885–891. | |

Roters S, Hamzei P, Szurman P, et al. Combined penetrating keratoplasty and vitreoretinal surgery with silicone oil: a 1-year follow-up. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241(1):24–33. | |

Dong X, Wang W, Xie L, Chiu AM. Long-term outcome of combined penetrating keratoplasty and vitreoretinal surgery using temporary keratoprosthesis. Eye (Lond). 2006;20(1):59–63. | |

Roters S, Szurman P, Hermes S, Thumann G, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Kirchhof B. Outcome of combined penetrating keratoplasty with vitreoretinal surgery for management of severe ocular injuries. Retina. 2003;23(1):48–56. | |

Garcia-Valenzuela E, Blair NP, Shapiro MJ, et al. Outcome of vitreoretinal surgery and penetrating keratoplasty using temporary keratoprosthesis. Retina. 1999;19(5):424–429. | |

Yan H, Cui J, Zhang J, Chen S, Xu Y. Penetrating keratoplasty combined with vitreoretinal surgery for severe ocular injury with blood-stained cornea and no light perception. Ophthalmologica. 2006;220(3):186–189. | |

Gallemore RP, Bokosky JE. Penetrating keratoplasty with vitreoretinal surgery using the Eckardt temporary keratoprosthesis: modified technique allowing use of larger corneal grafts. Cornea. 1995;14(1):33–38. | |

Gelender H, Vaiser A, Snyder WB, Fuller DG, Hutton WL. Temporary keratoprosthesis for combined penetrating keratoplasty, pars plana vitrectomy, and repair of retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(7):897–901. | |

Noorily SW, Foulks GN, McCuen BW. Results of penetrating keratoplasty associated with silicone oil retinal tamponade. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(8):1186–1189. | |

Ikeda T. Pars plana vitrectomy combined with penetrating keratoplasty. Semin Ophthalmol. 2001;16(3):119–125. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.