Back to Journals » Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity » Volume 13

Clinical Significance of Diabetic Dermatopathy

Authors Naik PP , Farrukh SN

Received 14 October 2020

Accepted for publication 26 November 2020

Published 8 December 2020 Volume 2020:13 Pages 4823—4827

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S286887

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Antonio Brunetti

Piyu Parth Naik,1 Syed Nadir Farrukh2

1Department of Dermatology, Saudi-German Hospitals & Clinics, Dubai, United Arab Emirates; 2Department of Internal Medicine, Adam-Vital Hospital, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Correspondence: Piyu Parth Naik

Department of Dermatology, Saudi-German Hospitals & Clinics, Hessa Street 331 West, Al Barsha 3, Exit 36 Sheikh Zayed Road, Opposite of American School, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Tel +971562173323

Email [email protected]

Abstract: Diabetic dermopathy is a cutaneous manifestation commonly seen in diabetes patients and was initially described by Melin in 1964. These lesions are well-demarcated, hyperpigmented macules or papules with atrophic depression and were commonly sighted on shins of the tibia with bilateral asymmetrical distribution and rarely seen on arms, thighs and abdomen. The incidence of DD ranges from 0.2 to 55%. It has been frequently associated with microangiopathic complications of diabetes such as nephropathy, retinopathy and polyneuropathy. Although the exact mechanism of occurrence is unknown, it may be related to impaired wound healing due to decreased blood flow, local thermal trauma or local subcutaneous nerve degeneration. Diagnosis is made by clinical examination and the differential diagnosis includes stasis dermatitis, early lesion of necrobiosis lipoidica and purpuric dermatitis. Prevention of dermopathy lesions includes optimized glucose control. No active treatment is recommended or proven effective and DD is known to resolve on its own as time passes. Modified collagen and high glycerine-based lotion have shown marked improvement in skin color changes due to diabetic dermopathy. Diabetic dermopathy is known to have a strong association with microangiopathic complications; the presence of such lesions must raise strong suspicion and prompt investigation for severe underlying pathology. Enhanced scrutinized glycemic control in diabetic dermatopathy patients can even lead to abatement in further progression to microvascular complications and improved long-term patient outcomes.

Keywords: diabetic dermopathy, diabetes mellitus, pretibial patches, cutaneous lesions in diabetics, microvascular disease

Introduction

Diabetic dermopathy was first reported by Hans Melin in 1964 and the term was coined by Binkley in 1965.1,2 Other phrases used interchangeably with diabetic dermopathy were shin spots, pigmented pretibial patches, diabetic dermangiopathy and spotted leg syndrome. These lesions have been reported to occur in 0.2–55% of diabetic patients. The lowest incidence was noted in a study conducted in India with 500 diabetic subjects, out of which only one was found to have diabetic dermopathy and the reason suggested was the darker skin complexion of Indians however, an exception was noted in a study from the western Himalayas with 36% diabetics showed DD.1,3,4 Melin described DD as small, circumscribed, brownish, atrophic skin lesions commonly seen on lower extremities.1 These lesions are asymptomatic, non-contagious and develop as single or clusters and are often asymmetric and bilateral. In his original article, Melin stated that these lesions were more or less specific to diabetes mellitus. Most of the reports published later agreed to his findings; however, other authors suggested finding similar lesions in non-diabetics.3 It is a frequent finding in older patients with a history of diabetes for a long duration and coexists with the microvascular disease.5 It is uncertain whether it has more predilection to type 1 or type 2 diabetes;6 no difference in prevalence among males or females was observed.7

Pathogenesis/Causes

The underlying pathogenesis of Diabetic dermopathy is unclear; however, several theories have been postulated. Melin suggested that DD’s occurrence was secondary to trauma as the lesions are asymptomatic and often go unnoticed by patients with the presumption that lesions might have arisen due to trauma.2 Experiments were conducted to mimic the lesions in vivo by striking the skin with a rubber hammer that was unsuccessful.

Binkely proposed that shins’ predilection was due to lower skin temperature, slow blood flow, increased plasma viscosity, and vessel fragility.2 Attempts to experimentally induce DD lesions with thermal stimuli induced atrophic, circumscribed skin lesions in people with diabetes; however, similar lesions were elicited in patients with amyloidosis.8

DD is neither caused by decreased local perfusion; instead, the lesion occurs due to the scarring process resulting from poor wound healing.9 The authors discovered that blood flow in lesions was increased rather than decreased, making local ischemia theory unlikely.

Subcutaneous nerve degeneration as the causative factor for dermopathy lesions was also suggested; however,10 the relation of microvascular complications of Diabetes and DD is the most acceptable explanation (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Pathogenesis of diabetic dermatopathy. |

Clinical Presentation

- Physical finding: Diabetic dermopathy is a clinical diagnosis. Biopsy of the lesions is rarely done due to poor wound healing concerns in diabetic patients’ lower extremities. Lesions are asymptomatic and the distribution is bilateral and asymmetric and commonly occur on shins and rarely found on thighs, arm, abdomen and trunk. The clinical findings stated in the original article of Melin and Binkely reported spontaneous onset of lesions as non-blanching, scaly, round or oval, red or purple macule or papules of size 1 to 2.5 cm with sclerosis and central depression or vesiculation might be found.1,2 These lesions, in due course, appear as characteristic scar-like lesions of diabetic dermopathy rather than ischemia.9 In established lesions, there may be a thin keratin scale.11,12 Each lesion usually lasts for about two years and the intensity of pigmentation corresponds to the degree of atrophy. New lesions appear as older lesions fade away.13,14

- Histopathology: Tissue specimens obtained and examined under a microscope after staining revealed epidermal and dermal changes.15 Atrophy with obliteration of rete ridges, hyperkeratosis and variable pigmentation in basal cells were seen in the epidermis. Increased collagen density, fragmentation of collagen fibers, thickening of collagen bundles, fibroblastic proliferation, and dermal edema were found in the dermis.1,2 There is increased hemosiderin and melanin deposition.15 Partial occlusion of vessel lamina, hyalinization of arterioles, increased capillaries and periodic deposition of Schiff stain was noted.12

- Cutaneous blood flow in dermopathy lesions: Patients with diabetic dermopathy showed reduced skin blood flow, which is due to increased duration of diabetes compared to non-diabetic, but flow levels were considerably higher in dermopathy sites when compared to contiguous uninvolved sites and did not show relative ischemia.9,16 Flow values over lesions were similar to those found in scar sites. It has been documented that blood flow increases over hypertrophic but not atrophic scars.16 These suggest that DD lesions are scars.

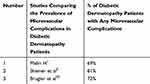

- Association of dermopathy with retinopathy and neuropathy: Diabetic dermopathy usually occurs before the onset of retinopathy and nephropathy.17,18 Melin’s original study reported increased predilection to retinopathy in inpatient with dermopathy lesions.1 69% of patients with DD reported retinopathy, whereas 25% without dermopathy presented with retinopathy. Dermopathy association with nephropathy (27%) and neuropathy (57%) was observed.1 Most studies conducted over time have shown similar results to Melin’s study.19 Shemer et al study showed that the incidence of diabetic dermopathy increased with an increasing number of complications, ie Diabetic dermopathy occurred in 21% of those with no microvascular complications, 52% with one complication, 57% of those with two complications and 81% of those with all three complications.5 It was reported by Brugler et al that nephropathy was observed in 72% patients of Type 1 diabetes and dermopathy.20 (Table 1)

- Association of Dermopathy with demographic characteristics: The number of dermopathy lesions shows a significant association with the duration of diabetes.15,18,21,22 Dermopathy is significantly associated with age and has shown more prevalence in 45–70 years.5,23,24

|

Table 1 Comparison of Studies Showing the Association of Diabetic Dermatopathy with Micro-Vascular Complications |

The number of dermopathy lesions showed an association with HbA1C levels.23,24 Lower incidence of dermopathy was reported in patients taking insulin when compared to oral medication users.5

Differential Diagnosis

- Early-stage lesions should be differentiated from fungal infections.

- Late-stage lesions should be differentiated from Pigmented purpuric dermatosis, Purpura annularis telangiectasia, Purpuric lichenoid dermatitis, Pigmented stasis dermatitis and Papulonecrotic tuberculid.2

- Other: Melanocytic lesion, Dermatofibroma, Pretibial pigmented lesions due to prolonged use of Minocycline or Quinolones

All lesions resulting in scarring process or poor wound healing come in differential diagnosis of Diabetic dermatopathy.25 The presence of a minimum of four classical lesions was considered diagnostic of Diabetic dermopathy.4

Treatment and Current Scenario

Diabetic dermopathy lesions are asymptomatic and known to resolve on its own hence, no treatment is required. Lesions typically last for 12 to 24 months and new lesions appear as older ones’ fades. Also, Diabetic dermopathy and HbA1C were found unrelated or in other words, variable improvement of lesions was found on glycaemic control.7,26 Due to a lack of clarity of pathogenesis, no measure has proven effective in treating these lesions. Cosmetic camouflage can disguise the lesions.

In 2019, Southwest technologies sponsored a product containing modified collagen plus glycerine lotion efficacy was evaluated among ten patients with DD. Furthermore, the lotion has shown promising results with no adverse events.

Conclusion and Future Prospects

The discovery of peculiar dermatological findings at classical sites, suspicious of diabetic dermatopathy, should spark the lightbulb in clinicians’ minds to investigate for diabetes in hitherto concealed cases.

Diabetic dermopathy is known to have a strong association with microangiopathic complications, the presence of such lesions must raise strong suspicion and prompt investigation for severe underlying pathology. There is a significant association between dermopathy and age, duration of diabetes, retinopathy and nephropathy; thus, it is recommended that patients with DD be examined for retinopathy, neuropathy and nephropathy.

Enhanced scrutinized glycemic control in diabetic dermatopathy patients can even lead to abatement in further progression to microvascular complications and improved long-term patient outcomes.

A non-invasive diagnostic tool called nail fold videocapillaroscopy has been used to evaluate dermal microvasculature in diabetics with retinopathy. This investigation tool can help study vasculature in relatively early stage of diabetes and have prospects for further study in dermopathy patients and associate findings with retinopathy.27 Also, infrared thermography studies can be done to evaluate the difference in temperature in the lesion and normal skin as there is a probability that higher temperature in lesions can indicate the probability of neuropathy, peripheral arterial disease of neuro-ischemia.28

Author Details

Dr. Piyu Parth Naik is a practicing dermatologist and Dr. Syed Nadir Farrukh is a practicing physician with a particular interest in endocrinology.

Ethical Approval

No ethical approval was required.

Funding

This article was self-funded and no other source of funding present.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. Melin H. An atrophic circumscribed skin lesion in the lower extremities of diabetics. Acta Med Scand. 1964;176(Suppl.423):9–75.

2. Binkley GW. Dermopathy in the diabetic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92(6):625–634. doi:10.1001/archderm.1965.01600180017003

3. Danowski TS, Sabeh G, Sarver ME, et al. Shin spots and diabetes mellitus. Am J Med Sci. 1966;251(5):570–575. doi:10.1097/00000441-196605000-00011

4. Ngo BT, Hayes KD, DiMiao DJ, et al. Manifestations of cutaneous diabetic microangiopathy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6(4):225–237. doi:10.2165/00128071-200506040-00003

5. Shemer A, Begman R, Linn S, Kantor Y, Friedman-Birnbaum RL. Diabetic dermopathy and internal complications in diabetes mellitus. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(2):113–115. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00273.x

6. Morgan AJ, Schwartz RA. Diabetic dermopathy: a subtle sign with grave implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(3):447–451. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.013

7. Romano G, Moretti G, Di Benedetto A, et al. Skin lesions in diabetes mellitus: prevalence and clinical correlations. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1998;39(2):101–106. doi:10.1016/S0168-8227(97)00119-8

8. Lithner F. Cutaneous reactions of the extremities of diabetics to local thermal trauma. Acta Med Scand. 1975;198(1–6):319–325. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820.1975.tb19548.x

9. Wigington G, Ngo B, Rendell M. Skin blood flow in diabetic dermopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(10):1248–1250. doi:10.1001/archderm.140.10.1248

10. Kiziltan ME, Benbir G, Akalin MA. Is diabetic dermopathy a sign for severe neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus? Nerve conduction studies and symptom analysis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(8):1862–1869. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2006.05.007

11. Port M. Diabetic dermopathy: a controversy in dermatology. J Am Podiatry Assoc. 1982;72(8):418–423. doi:10.7547/87507315-72-8-418

12. Bauer MF, Levan NE, Frankel A, Bach J. Pigmented pretibial patches. A cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Arch Dermatol. 1966;93(3):282–286. doi:10.1001/archderm.1966.01600210018003

13. Houck GM, Morgan MB. A reappraisal of the histologic findings of pigmented pretibial patches of diabetes mellitus. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31(2):141–144. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2004.00133.x

14. Stulberg DL, Clark N, Tovey D. Common hyperpigmentation disorders in adults, part II: melanoma, seborrheic keratoses, acanthosis nigricans, melasma, diabetic dermopathy, tinea versicolor, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1963–1968.

15. McCash S, Emanuel PO. Defining diabetic dermopathy. J Dermatol. 2011;38(10):988–992. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01251.x

16. Timar-Banu O, Beauregard H, Tousignant J, et al. Development of noninvasive and quantitative methodologies for the assessment of chronic ulcers and scar in humans. Wound Repair Regen. 2001;9(2):123–132. doi:10.1046/j.1524-475x.2001.00123.x

17. Ahmed K, Muhammad Z, Qayum I. Prevalence of cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus. J Ayub Med Coll. 2009;21(2):76–79.

18. George SM, Walton S. Diabetic dermopathy. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis. 2014;14(3):95–97. doi:10.15277/bjdvd.2014.027

19. Abdollahi A, Daneshpazhooh M, Amirchaghmaghi E, et al. Dermopathy and retinopathy in diabetes: is there an association? Dermatology. 2007;214(2):133–136. doi:10.1159/000098572

20. Brugler A, Thompson S, Turner S, Ngo B, Rendell M. Skin blood flow abnormalities in diabetic dermopathy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(3):559–563. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.010

21. Juturu V. Skin Health and Metabolic Complications.Bioactive Dietary Factors and Plant Extracts in Dermatology. Springer; 2013:39–47.

22. Brzezinski P, Chiriac AE, Pinteala T, Foia L, Chiriac A. Diabetic dermopathy (“shin spots”) and diabetic bullae(“bullosis diabeticorum”) at the same patient. Pak J Med Sci. 2015;31(5):1275–1276. doi:10.12669/pjms.315.7521

23. Zoungas S, Chalmers J, Ninomiya T, et al. Association of HbA1c levels with vascular complications and death in patients with type 2 diabetes: evidence of glycaemic thresholds. Diabetologia. 2012;55(3):636–643. doi:10.1007/s00125-011-2404-1

24. Chatterjee N, Chattopadhyay C, Sengupta N, Das C, Sarma N, Pal SK. An observational study of cutaneous manifestations in diabetes mellitus in a tertiary care Hospital of Eastern India. Indian J Endocrinol Metabol. 2014;18(2):217–220. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.129115

25. Jelinek JE. Skin disorders associated with diabetes mellitus. In: Rifkin H, Porte D, editors. Ellenberg and Rifkin’s Diabetes Mellitus, Theory and Practice. New York: Elsevier; 1990:

26. Mahajan S, Koranne RV, Sharma SK. Cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:105–108.

27. Bakirci S, Celik E, Acikgoz SB, et al. The evaluation of nailfold videocapillaroscopy findings in patients with type 2 diabetes with and without diabetic retinopathy. North Clin Istanb. 2018;6(2):146–150. doi:10.14744/nci.2018.02222

28. Sibbald RG, Mufti A, Armstrong DG. Infrared skin thermometry: an underutilized cost-effective tool for routine wound care practice and patient high-risk diabetic foot self-monitoring. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2015;28(1):37–44. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000458991.58947.6b

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.