Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 16

Chilean Patients’ Perception of Their Oral Health-Related Quality of Life After Bichectomy

Authors Velasquez F, Nuñez E, Gutiérrrez JD, Aravena PC

Received 29 January 2022

Accepted for publication 11 August 2022

Published 29 September 2022 Volume 2022:16 Pages 2721—2726

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S360471

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Fabiana Velasquez,1 Evelyn Nuñez,1 Juan Diego Gutiérrrez,2 Pedro Christian Aravena3

1School of Dentistry, Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia, Chile; 2Private Practice, Clinica Oi, Santiago, Chile; 3Institute of Anatomy, Histology and Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia, Chile

Correspondence: Pedro Christian Aravena, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Austral de Chile, #1640 Rudloff Street, Valdivia, Chile, Tel/Fax +56 63293751, Email [email protected]

Objective: To describe the quality of life associated with oral health in patients who have had bichectomy surgery in Chile using the Spanish version of the health-Related Quality of Life instrument (HRQOL-sp).

Material and Methods: We designed a cross-sectional study. The HRQOL-sp scale was administered to dental patients in a private clinic who had bichectomy surgery between December 2020 and June 2021. The HRQOL-sp instrument has four domains: oral function, general activity, postoperative signs, symptoms or complications, and pain level. The instrument was administered by telephone survey on days 1, 3, 5 and 7 post-surgery. Interference in quality of life was defined as when patients selected the options “quite a few problems” or “many problems” for oral function and general activity. Signs and symptoms related to post-surgical complications and pain were also described with a verbal rating scale from one to ten. All results were compared between postoperative days according to the domains of the HRQOL-sp scale.

Results: Seventy-three patients (age 27.75 ± 8.06 years; 93.15% female) participated. Bichectomy patients report the highest interference in quality of life on the first postoperative day because most were unable to chew (71.23%). On the first and third postoperative days, the most frequent complication was swelling (97.26%), and on the fifth day was ecchymosis (42.47%). The average worst perceived pain was 3.34± 2.32 on the verbal analogue scale. The rest of the evaluated items significantly decreased towards the seventh postoperative day (p< 0.05).

Conclusion: Interference in quality of life associated with bichectomy surgery is greatest on the first postoperative day. Complications and pain levels decreased significantly over time.

Keywords: quality life, complications, bichectomy, dentistry, oral surgery

Introduction

Bichectomy surgery is the excision of the adipose pouch of the cheek located between the masseter and buccinator muscle. It is an aesthetic and functional surgery that improves facial harmony and mastication1 with a decrease in the volume of the buccal region, achieving a safe facial recontouring, increase of the malar prominence.2 Bichectomy surgery is an increasingly common treatment in dental practice for functional or aesthetic problems. However, the size of the excision varies between patients. In most cases, the excision is very small, but it can be very large in patients with an oval or rounder face. Large adipose pouches can cause occlusal interference by forcing the internal face of the cheek in the occlusion, generating ulcerations or hyperkeratosis of the mucosa called “morsicatio buccarum”.3

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is defined as “those aspects of self-perceived well-being that are related to or affected by the presence of a disease or treatment.4 Oral health-related quality of life reflects people’s comfort in eating, sleeping, participating in social interaction, self-esteem, and satisfaction with their oral health.5 Psychometric instruments, such as the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP), have been used to describe the quality of life associated with oral health.2,6 The original instrument has 49 items representing 7 domains7 and has been validated in Spanish,8 Italian9 and even reduced and simplified to 5 items.10 However, there are no records on the HRQOL of bichectomy patients in Spanish-speaking databases, so longitudinal studies and large numbers of participants are impossible.

A previous report on the quality of life associated with oral health has made it possible to evaluate the post-surgical quality of life in third molar surgery using the Oral Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) instrument in Spanish (HRQOL-sp).5,11,12

Considering this background, the aim of our study is to describe the quality of life related to the perception of oral health according to the HRQOL-sp scale and to quantify post-surgical complications during seven postoperative days in patients of Chilean population under bichectomy surgery. In other hand, this report outlines how bichectomy surgery affects the different domains that influence patient quality of life and can adequately inform them.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was designed in patients treated in a private dental clinic in the city of Valdivia, Chile, who underwent bichectomy surgery between December 2020 and June 2021. Male and female patients who were over 18 years old, belonged to the American Society of Anesthesiologists ASA I classification, and who had signed an informed consent form were selected to participate. Patients taking antibiotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or corticosteroids and those who did not comply with the protocol and time required by the study were excluded. This study was approved by the Ethics and Scientific Committee of the Health Service of Valdivia (n° 414/2020) complying with the ethical commitments of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample Size

We calculated our minimum sample size considering the preliminary results of Aravena et al11 who observed 51% of subjects with oral opening problems associated with oral surgery on the first postoperative day. Therefore, we considered that at least 25% of our patients would present these problems, with an alpha value of 5% and a power of 20%. We also estimated that we would lose an additional 25% of subjects during follow-up, so our minimum sample size was 38 participants (algorithm: “power one proportion 0.25 0.51, test (wald)” STATA v.14.0. StataCorp, TX, USA).

HRQOL-Sp Scale

The HRQOL-sp instrument was adapted to Spanish11 and measured the perception of quality of life associated with oral health patients’ postoperative recovery. It has four domains: oral function (eating, chewing, opening the mouth and being able to speak), general activity (sleep, daily routine, social life and hobbies or sports), postoperative signs or symptoms and pain level (measured by the Verbal Rating Scale [VRS ). For oral function and general activity, four alternatives were presented on a Likert scale: “no problems”, “little problems”, “quite a lot of problems”, and “many problems.11 The presence of signs and symptoms was assessed dichotomously (yes/no), and the pain level was assessed using average VRS values on the follow-up day (VRS values were from 0 [no pain] to 10 points [worst pain imaginable]).

). For oral function and general activity, four alternatives were presented on a Likert scale: “no problems”, “little problems”, “quite a lot of problems”, and “many problems.11 The presence of signs and symptoms was assessed dichotomously (yes/no), and the pain level was assessed using average VRS values on the follow-up day (VRS values were from 0 [no pain] to 10 points [worst pain imaginable]).

Bichectomy Surgery Procedure

Bichectomy surgery was performed by only one surgeon (PA). All patients were medicated with a dose of Amoxicillin 500 mg and Naproxen 550 mg one hour before surgery and used mouthwash with 0.12% chlorhexidine digluconate and 0.05% cetylpyridinium chloride (Perio-Aid® Treatment, alcohol-free; Dentaid, Spain) for thirty seconds. Local anesthesia with 1.8mL (one cartridge) of Lidocaine 2% with Epinephrine 1:80,000 (Xylonor 2% Special, Septodont®, France) was used on the posterosuperior alveolar nerve and buccal nerve in the internal face of the cheek around the parotid excretory duct. After local anesthesia, the incision site was located at the maximum opening of the mouth, one centimeter posterior to the parotid excretory duct, and at the level of the second upper molar on the occlusal side. A vertical incision of 1 cm in length was made with a scalpel blade n° 15C until the cheek adipose pocket’s bright yellow buccal fat pad was observed. The fat was avulsed using Kelly forceps, and the blunt instrument was extended towards the temporal and genian region until mobile fat was obtained. Care was taken not to damage the vascular pedicle. The fat was removed, the wound was cleaned with 0.9% saline irrigation and hemostasis, and the wound was closed with two 4.0 silk stitches (Ethicon, USA), indicating local compression with gauze.

All patients were prescribed relative rest for 3 days, a cold diet for 24 hours and a soft diet for 3 days. All patients were also prescribed Naproxen 550 mg every 8 hours for 3 days, a mouthwash of 10 mL of chlorhexidine 0.12% for 30 seconds every 12 hours for 6 days, and local compression of the cheeks with local cold for one day.

HRQOL-Sp Scale Application

Before surgery, a researcher (FV) presented the scale and gave a printed copy to each patient, along with a verbal explanation of its content and how to answer it. Telephone calls were made to obtain the responses on the first, third, fifth and seventh postoperative days. The same researcher read the questions and gave the patient response options for oral function, general activity, signs or symptoms and quantification of pain. If the patient did not respond to phone calls during follow-up or responded incompletely, their data and records were discarded from the study.

On the seventh postoperative day, patients returned to the clinical office for a review. Finally, the data were stored in an electronic database in Google Drive (Google Inc. Mountain View, CA, USA), coding the patients’ registration numbers and personal data.

Data Analysis

Patients’ sociodemographic variables such as: age, sex (male/female), schooling (primary/secondary/higher), tobacco use and contraceptive use (in women) were recorded. Substantial interference in quality of life was considered when patients answered “many problems” or “quite a lot of problems” to the questions in the oral function and general activity domains. The presence of signs or symptoms (yes/no) and the average pain level were quantified with the verbal rating scale (VRS) (range 0 to 10).

The mean and standard deviation was calculated for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentage distribution were used for categorical variables. The frequency of items that substantially interfered with quality of life, postoperative signs and symptoms and the average pain between postoperative days were compared (chi-square and Anova p<0.05). The results were presented as means in tables and graphs using the Stata v.14.0 program (STATA Corp. TX, USA).

Results

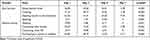

Eighty-seven patients agreed to participate. Fourteen did not respond to telephone calls, so 73 were selected for the study. 68 (93.15%) were women. The mean age of participants was 27.75 ± 8.06 years (range 18–55 years). Details of characteristics and clinical data of the study subjects are in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Sociodemographic Characteristics and Clinical Data of the Patients Included in the Study (n=73) |

First, we analyzed the “Oral Function” and “General Activity” domains. The number of patients who reported substantial interference in the quality of life significantly decreased between the first postoperative day and the following days (p<0.01) for all items in these domains. On the first postoperative day, the item that caused the most interference in quality of life was “Chewing” (71.23%), followed by “Opening the mouth to the maximum” (61.64%). Conversely, sleeping was the item that caused the least interference (10.96%) (Table 2).

Inflammation was the most frequent complication but decreased significantly on the seventh postoperative day (81.94%; p=0.001). Ecchymosis was significantly more frequent on the fifth day (42.47%; p<0.001). Most patients did not report bleeding, nausea, bad taste, or food accumulation (less than 7% on all postoperative days (p<0.05) (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Percentage of Patients with Signs or Symptoms per Postoperative Day (n=73) |

Patients reported the worst perceived pain on the first postoperative day (mean 3.34±2.32 points of VRS) (Figure 1). Perceived pain decreased significantly on the third, fifth and seventh postoperative days compared to the first (mean 2.56, 2.01 and 1.46 point of VRS, respectively [p<0.001; Anova-Bonferroni test]). The maximum worst pain recorded was 10 on day 1 and decreased towards the end of the follow-up.

|

Figure 1 Mean and 95% Confidence Interval of the worst pain perceived according to the verbal rating scale (VRS) per postoperative day (n=73). |

Discussion

The purpose of our study was to determine the quality of life associated with oral health according to HRQOL-sp in a Chilean population. As a result, participants’ quality of life related to their oral function and general activity was most affected in the first 3 postoperative days. Signs and symptoms and pain levels decreased significantly over time. From the above, it can be concluded that bichectomy is a surgery with a rapid recovery. There were no reports of significant interferences in the quality of life on the seventh postoperative day, and all participants returned to their daily activities without major problems.

The purpose of bichectomy surgery is to improve facial harmony and mastication of patients.2 For this purpose, a previous multidisciplinary evaluation is important to achieve esthetic harmony between the face, teeth, lips and gums, with several dental specialties to solve the complexity of each patient’s case.13

Most bichectomy patients were female or under 30 years old. Women are more connected to self-care and seek more health services and cosmetic procedures than men.2 All participants reported they were undergoing the procedure to improve the harmony of their faces.

Corso et al2 found the most common postoperative complications reported by their participants were oedema and trismus. However, the most frequent complications reported by our participants were chewing problems, swelling or oedema. Additionally, ecchymosis was the second most prevalent postoperative sign in our study, with 45.9% of patients reporting it on postoperative day.5

The data collected from the HRQOL-sp scale through telephone calls could have contributed to the patient’s recovery.11 Our participants reported feeling accompanied during their recovery and more reassured during their postoperative period because their health status was constantly verified. Additionally, although bichectomy is a safe surgery without major post-surgical complications and a good prognosis, correct patient evaluation before surgery is essential for accurate diagnoses and avoiding unrealistic patient expectations. For example, according to Faría et al3 there is still doubt about recommending the surgery in cases of asymmetry between the Bichat fat pads because there is a risk of asymmetry in the postoperative period. Furthermore, when the fat pad volume is small, the surgeon must discuss the subtle outcomes with the patient.

Our study is limited because it cannot be compared with previous studies. Additionally, there has been little previous research on bichectomy surgery, and there is no way to compare studies.2 However, we used a validated instrument to measure quality of life in oral health used to evaluate other oral surgeries. We avoided interviewer bias by giving all participants a paper copy of the scale, which was explained to them after surgery. Additionally, the patients’ understood and became familiar with all the items during the telephone calls.

In conclusion, the HRQOL-sp instrument found that bichectomy surgery produces substantial interference to quality of life during the first three postoperative days. Signs and symptoms and pain levels decreased significantly towards the end of the postoperative period. Further studies assessing oral health quality of life-related to bichectomy are needed.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in relation to this work. This article was financially supported by the Graduate School of the School of Medicine and the Rectory of Research, Development and Artistic Creation of the Universidad Austral de Chile (VIDCA) of the Universidad Austral de Chile.

References

1. Dean A, Alamillos F, García-López A, Sánchez J, Peñalba M. The buccal fat pad flap in oral reconstruction. Head Neck. 2001;23(5):383–388. doi:10.1002/hed.1048

2. Cotait de Lucas Corso P, Bonetto L, Tórtora G, et al. Evaluation of quality of life profile of patients submitted to bichectomy. RSBO. 2019;16(1):11–15. doi:10.21726/rsbo.v16i1.529

3. Faria C, Dias R, Daher CA, Caetano R, Barcelos L. Bichectomy and its contribution to facial harmony”. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2018;33(4):446–452.

4. Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(7):645–649. doi:10.1007/s40273-016-0389-9

5. Conrad SM, Blakey GH, Shugars DA, Marciani RD, Phillips C, White RP. Patients’ perception of recovery after third molar surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57(11):1288–1294. doi:10.1016/S0278-2391(99)90861-3

6. Calixto da Silva D, Da Silva Almeida F, Melo NT, Guimaraes D, Santos FK. Effects of dexamethasone and Low-level laser therapy on pain, swelling and quality of life after buccal fat pad removal: a clinical trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;78(11):

7. Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Health. 1994;11(1):3–11.

8. Lopez R, Baelum V. Spanish version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-Sp). BMC Oral Health. 2006;6:11. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-6-11

9. Covello F, Ruoppolo G, Carissimo C, et al. Multiple sclerosis: impact on oral hygiene, dysphagia, and quality of life. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3979. doi:10.3390/ijerph17113979

10. Simancas-Pallares M, John MT, Enstad C, Lenton P. The Spanish language 5-item oral health impact profile. Int Dent J. 2020;70(2):127–135. doi:10.1111/idj.12534

11. Aravena PC, Delgado F, Olave H, Ulloa-Marin C, Perez-Rojas F. Chilean patients’ perception of oral health-related quality of life after third molar surgery. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;6(10):1719–1725. doi:10.2147/PPA.S106814

12. Shugars DA, Benson K, White RP, Simpson KN, Bader JD. Developing a measure of patient perceptions of short-term outcomes of third molar surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54(12):1402–1408. doi:10.1016/S0278-2391(96)90253-0

13. Espíndola-Castro LF, de Melo Monteiro GQ, Ortigoza LS, da Silva CHV, Souto-Maior JR. Multidisciplinary approach to smile restoration: gingivoplasty, tooth bleaching, and dental re-anatomization. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2019;40(9):590–599.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.