Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 12

Characteristics of physicians who prescribe opioids for chronic pain: a meta-narrative systematic review

Authors Hooten WM , Dvorkin J , Warner NS, Pearson ACS , Murad MH , Warner DO

Received 21 January 2019

Accepted for publication 25 June 2019

Published 24 July 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 2261—2289

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S202376

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Erica Wegrzyn

W Michael Hooten,1 Jodie Dvorkin,2 Nafisseh S Warner,1 Amy CS Pearson,3 M Hassan Murad,4 David O Warner1

1Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN, USA; 2Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, Minneapolis, MN, USA; 3Department of Anesthesia, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA, USA; 4Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN, USA

Background: The primary objective of this systematic review was to identify the characteristics of physicians who prescribe opioids to adults with chronic pain. This review was limited to studies examining fully-trained physicians, as relevant characteristics of resident physicians and non-physician clinicians may differ.

Methods: A comprehensive search of databases from January 1, 1980 to December 5, 2017 was conducted. Eligible study designs included (1) randomized trials; (2) nonrandomized prospective and retrospective studies; and (3) cross-sectional observational studies. The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using an adapted version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional studies. A total of 2508 records were screened and 22 studies met inclusion criteria. The majority of studies were cross-sectional (n=20) and the total number of participants was 8433.

Results: The risk of bias was high overall. The majority of physicians were confident managing and prescribing opioids for chronic pain but had high levels of dissatisfaction. Physicians reported high awareness of the potential for opioid misuse and were concerned about inadequate prior training in pain management. The majority of physicians were less likely to prescribe for patients with a history of substance abuse and reported major concerns about regulatory scrutiny.

Conclusion: This systematic review provides the foundation for the development of prospective studies aimed at further elucidating the constellation of mechanisms that influence physicians who manage pain and prescribe opioids.

Keywords: systematic review, opioid, prescription, physician characteristics

Introduction

Nonmedical use of prescription opioids remains a public health crisis.1 Despite recent reductions in opioid prescribing, the quantity of prescribed opioids remains substantially elevated compared to the quantities prescribed prior the year 2000.2,3 The decline in opioid prescribing has been accompanied by a sharp rise in overdose deaths attributed to illicitly manufactured fentanyl while overdose deaths attributed to heroin have plateaued.4 As national prescribing guidelines5 and public health campaigns6 heighten awareness of the risks associated with long-term opioid therapy initiated for chronic pain, it is apparent that some opioid prescriptions originally intended for short-term use lead to unintended prolonged opioid use (UPOU).7–16

Our group has recently published a conceptual framework for understanding UPOU.17 The overall goal of a conceptual framework is to provide a working schema to drive future hypothesis generation. In the absence of standardized methods for developing a conceptual framework, the process involves identifying corroborative evidence and coalescing expert opinion during the adjudication of factors intended for framework inclusion. The UPOU framework is comprised of 3 domains, including patient characteristics, practice environment characteristics, and opioid prescriber characteristics. The framework posited that characteristics of physicians that could influence prescribing behaviors include (1) training in pain management and opioid use; (2) personal attitudes and beliefs about opioids; and (3) perceived professional obligation to treat patients with chronic pain. As prescribers serve as the gatekeepers to prescription opioid access, the focal point of the framework is the opioid prescriber domain; the effects of the other two domains are ultimately mediated by individual prescribing behavior.

The primary objective of this systematic review was to identify the characteristics of physicians who prescribe opioids to adults with chronic pain. Secondary objectives included describing patient and practice environment factors that affect physicians who manage and prescribe opioids for chronic pain. This review was limited to studies examining fully-trained physicians, as relevant characteristics of resident physicians and non-physician clinicians may differ.

Methods

This systematic review was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.18 An a priori protocol was followed.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search of databases from January 1, 1980 to December 5, 2017 was conducted. The databases included MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, Medline In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus. The search strategy was designed and conducted by a medical reference librarian with input from the principal investigator. No language restrictions were applied. Controlled vocabulary supplemented with keywords was used to search for studies on practitioner characteristics influencing opioid prescribing practices. The actual search strategy is provided in Supplementary materials.

Study selection process

Eligible study designs included (1) randomized-, crossover-, and parallel-designed clinical trials; (2) nonrandomized prospective and retrospective longitudinal studies; and (3) cross-sectional observational studies. Based on our conceptual framework, inclusion criteria included all studies that reported information about (1) physician attitudes and beliefs about opioid use; (2) previous training in pain and opioid management; (3) professionalism; or (4) physician demographics. Exclusion criteria included (1) studies that mixed physician and non-physician data; (2) studies that reported data derived from physician responses to clinical vignettes; (3) data from medical students and residents-in-training; (4) studies of non-physicians and non-US physicians; and (5) qualitative studies that reported data from individual physician interviews.

The studies identified by the search strategy were screened in two phases. First, two independent pairs of reviewers screened all titles and abstracts. Second, the full text of all studies identified in the first phase were screened by two independent pairs of reviewers.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by four independent reviewers using a templated electronic database. Based on the study inclusion criteria and conceptual framework, abstracted data were initially organized into four main categories (attitudes and beliefs; previous training in pain management; professionalism; physician demographics). Following abstraction, data were reorganized into four main categories and several subcategories: (1) physician factors (main category) with subcategories including attitudes and beliefs about opioid use, pain training and knowledge, awareness of adverse events, and opioid management practices; (2) patient factors (main category) with subcategories including pain etiology and comorbid conditions, and patient satisfaction; (3) practice environment (main category) with subcategories including regulatory scrutiny and clinical resources; and (4) physician demographics. No information was identified about physician professionalism. Other data abstracted included (1) author and year of publication; (2) study design; (3) survey type; (4) total number of study participants targeted for recruitment; (5) number of participants completing the study; (6) overall response rate; and (7) physician demographics including age, sex, years of practice, practice environment (ie, group, solo, hospital-based) and practice location (ie, rural, urban); (8) source of study funding.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed by two independent reviewers using an adapted version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional studies.19 The adapted version is comprised of 3 domains (eg, selection, comparability and outcome) and has been

used in previous systematic reviews that involved cross-sectional studies.20–22 We did not calculate an overall score because this practice has been discouraged; rather, we made an overall judgement about the risk of bias focusing on the comparability domain. Reviewer discrepancy was resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer.

Evidence synthesis

Due to the heterogeneity in study characteristics, settings, and outcomes a meta-analysis was not feasible; thus, results are presented using a meta-narrative approach. A meta-narrative review can be used when an area in inquiry has been researched using disparate methods by different groups of investigators.23,24 This approach is particularly useful when the definition of key terms or clinical factors vary between studies. Meta-narrative methods have been used to study various populations of patients with chronic pain.25–29 Data were summarized using themes drawn from our conceptual framework and using descriptive statistics.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

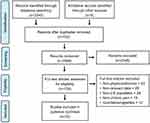

A flow diagram of the study selection process is depicted in Figure 1. A total of 22 studies met inclusion criteria (Table 1). The majority of studies were cross-sectional (n=20) where participants completed a survey at a single time point. Two studies used a repeated measures design; one study assessed participants pre-, post- and 6-months following a pain focused educational module30 and one study assessed participants pre- and 2-years following an initiative to improve opioid prescribing safety.31 The surveys were completed using email or internet-based software (n=10),30,32–40 postal system (n=7),41–47 in-person completion of a paper version (n=2),31,48 and a combination of postal and email approaches (n=3).49–51 Three studies pilot tested surveys in small groups of physicians prior to use41,48,49 and a single study used a validated survey.39 A total of 23,726 physician participants [median =1042; 25th to 75th interquartile range (IQR), 271 to 2492; range, 46 to 6962] were targeted for study recruitment and 8433 (median =254; 25th to 75th IQR, 189 to 418; range, 33 to 1912) completed the surveys. Six studies did not report the total number of targeted participants32–34,39,40,50 and a single study did not report the number of participants completing the survey.50 The median response rate for completion of the surveys was 35% (25th to 75th IQR, 26 to 58; range, 9 to 74); the response rate was not reported in 3 studies.32–34

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1 Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow chart of the study selection process. Note: Reproduced from Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. Creative Commons license and disclaimer available from: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode"http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode.18 |

Study funding

The sources of funding were reported in 15 studies. Four studies received funding from the National Institutes of Health,48,49 or a combination of state and federal government agencies.33,37 Private foundations or universities provided funding for 5 studies.30,42,45,47,51 A single study received funding from a state government agency and a private foundation.50 Five studies received funding from industry; 4 of the 5 funding sources were from the pharmaceutical industry32,40,41,46 and the remaining study was funded by a health information company.34 The funding source for 1 study was not reported but 2 co-authors were employed by a pharmaceutical company.39

Risk of bias evaluation

Table 2 contains the judgements made about each item of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for each study. The studies had major limitations in the comparability domain because of variations in study design and lack of study controls. Limitations were also noted in the selection domain due to variations in sample size and response rates. Similarly, limitations were noted in the outcome domain due to differences in methods used to perform the outcome assessment and variations in statistical analyses. Overall, the risk of bias was considered to be high across this body of evidence.

|

Table 2 Quality assessment using the adapted Newcastle-Ottawa scale for cross-sectional studies |

Prescriber characteristics

Demographics

A national sample was used in 9 studies32,34,35,39–41,46,49,51 and the 13 studies with state-level data were drawn from Massachutes,43 Michigan,42 Minnesota,31 Ohio,45 Pennsylvania,30,38 Texas,36 Utah,37 Washington,33,50 West Virginia,44 and Wisconsin.47,48 The majority of participants (range, 70% to 100%) were primary care physicians in 6 studies,35–38,44,48 and the participant samples were comprised of mixed specialties in 8 studies.30,32,34,39,41–43,49 The mean or median age of participants was reported in 5 studies41,42,45,48,51 and ranged from 41 to 51 years. The age range was reported in 3 studies32,39,44 in which the majority of participants were 35 to 60 years of age. Participant sex was reported in 11 studies30,32,35,36,39,41,42,44,45,48,51 with the proportion of male participants ranging from 49% to 86%. Race was reported in 4 studies35,36,42,51 with the majority of physicians identified as “white” (range, 70% to 84%). The mean years of practice reported in 5 studies30,32,43–45 ranged from 16 to 20 years and the majority of physicians in a single study had been in practice greater than 15 years.39 In 4 studies,36,38,41,49 the majority of participants resided in urban areas (range, 52% to 91%) and, in 3 studies,39,41,44 the majority of participants were in private or group practice.

Attitudes about pain and opioids

The majority of participants (73% to 88%) in 4 studies,32,35,43,50 which represented a mixture of primary care physicians and specialists, reported feeling confident, comfortable or competent prescribing opioids and managing pain. Several studies described physician satisfaction treating patients with chronic pain. Five studies that reported information related to the physician’s beliefs about pain and opioids were published between 2011 and 201531,35,37,38,50 and 2 studies were published earlier in 200142 and 2005.44 High levels of dissatisfaction treating chronic pain were reported in 2 studies where 81% were not satisfied prescribing opioids35 and 85% were frustrated treating patients with chronic pain.44 In a single study of university-based community physicians in Utah, satisfaction treating patients with chronic pain was assessed using a zero to 100 point visual analog scale where zero indicated no satisfaction and 100 indicated “much” satisfaction.37 The median response of the 47 physicians was 16.37 Alternatively, the majority of participants in a physician sample from Michigan were satisfied treating patients with chronic pain,42 and 42% to 52% of physicians from Washington were moderately to extremely satisfied treating chronic pain.50

Pain training and knowledge

Information about training in pain management was reported in 12 studies30,31,33,37,38,40,42,44–48 but the level of detail about training varied. In 5 studies30,31,37,47,48 published between 2006 and 2016, 32% to 72% of participants reported previous training in pain management. More specifically, in a study that involved 47 physicians working in a university-based community clinic system, 39% reported previous training about opioids during medical school, 70% reported training during residency, and 72% reported receiving opioid-related continuing medical education (CME).37 Despite previous training, 54% continued to report inadequate training about opioids and 85% reported the need for additional training in addiction.37 Similarly, in another study, 51% reported previous pain management training but only 43% reported having “good” to “excellent” knowledge about pain management.47 An earlier study published in 200142 reported that 10% of participants had received pain management training and younger age was associated with a greater likelihood of receiving previous training. In 3 studies that span 19 years,40,44,46 the majority of participants reported that previous pain management training was inadequate.

Physician participation and support of CME for chronic pain varied. In a national study,31 pain specialists had devoted an average of 76 hrs of CME to pain management in the past three years compared to an average of 10 hrs for primary care providers (PCPs). For PCPs, there was a significant correlation between the number of CME hours and the level of confidence in treating musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain, being in favor of mandatory pain education, and treating with NSAIDs and tramadol.31 In a separate study,37 72% of physicians in a Utah university-based community clinic system (70% were PCPs) reported participating in an average of 5.25 hrs of pain management CME activities over the past 2 years. In one study in Washington,33 79% to 84% of participants agreed that internet-based CME about pain management would be helpful.

Awareness of adverse events

The majority of participants (54–87%) reported some level of concern about opioid misuse, addiction, overdose, or diversion.32,33,35,36,43,44,47–49,51 Opioid tolerance was identified as an impediment to long-term efficacy in 3 studies.40,46,48 In a single study, 81–92% of participants reported that lost medications, request for early refills, persistent requests for opioids, and modifying opioid prescriptions were predictive of abuse.37 Concerns about other adverse effects were described in 2 studies including nausea and vomiting, constipation, dizziness, drowsiness, and drug interactions.32,48 In a study from Ohio’s Appalachian counties, 36–40% of physicians perceived that patient fear of addiction and other adverse opioid effects were barriers to successful management of chronic pain.45

Opioid management

Important areas about opioid management included knowledge and use of prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMP), urine drug screen (UDS), and opioid contracts. In 3 studies published between 2011 and 2016,33,37,51 77–91% endorsed use of PDMP. However, there was greater variability regarding the use of opioid contracts. In a study published in 2016, 98% of respondents “somewhat” or “strongly” supported use of opioid contracts.51 A 2011 study demonstrated that 64% of participants reported requiring patients to sign agreements38 and 89% of participants in a 2013 study reported “always” or “sometimes” having documentation of a medication contract.37 In 2 studies published in 2015,34,50 only 32–51% reported always requiring opioid contracts. Similarly, less consensus was observed for use of UDS. In 3 studies published between 2010 and 2016,37,38,50 19–47% of participants reported use of UDS but in a single study published in 2016,51 88% of a national sample “somewhat” or “strongly” support use of UDS.

Patient factors

Pain etiology and co-existing conditions

Pain etiology and comorbid conditions influenced physicians' prescribing practices. In 2 studies,44,47 over 90% endorsed not prescribing to patients with a substance abuse history, and 60% to 81% reported reviewing the patient’s history for a substance abuse disorder prior to prescribing opioids.50 The majority of physicians were more likely to prescribe opioids to patients with cancer-related pain compared to individuals with chronic nonmalignant pain.48,49 In one study, 62% of physicians did not prescribe opioids for fibromyalgia and 49% did not prescribe opioids for chronic headache.49

Patient satisfaction

Although 74% of physicians in a national survey reported that pain management was a priority, 62% were concerned about “disagreement” with patients about opioids.35 In a study from a Veterans Affairs hospital, the majority of physicians reported concerns that lowering opioid doses would upset patients.31 In a single study, other physician perceived barriers to chronic pain management included patient reluctance to make lifestyle changes (88%), financial burden for the patient (73%), and lack of patient transportation (57%).45

Practice environment

Regulatory scrutiny

Varying levels of concern about regulatory scrutiny were reported to influence prescribing practices. For example, 53–68% of participants in 3 studies based on state level data from Ohio,45 West Virginia,44 and Wisconsin47 reported that regulatory concerns influenced opioid prescribing practices. Alternatively, in 2 studies35,41 based on national samples, 16–32% reported that potential regulatory scrutiny influenced prescribing practices.

Clinical resources

In 2 studies, 78–85% of physicians reported that access to a pain specialist would be helpful.32,33 Lack of access to pain specialists was identified as a barrier to chronic pain management by 53–78% physicians in 3 studies.35,37,45 The use of clinical guidelines and standardized approaches to manage opioids varied. In a 2013 study,37 26% reported lack of agreement among physicians and clinic staff regarding prescription of opioids for chronic pain. However, 100% of physicians (n=48) working at a Veterans Affairs hospital agreed that it was important to have a consistent standard for prescribing opioids.31 In 2 studies, 56–68% reported that opioid prescribing policies, guidelines, algorithms or an opioid tracking system were available in their clinical setting.33,48 The presence of a clinical system to track patients using opioids was associated with a 2.5 greater odds of performing UDS.48 Managing chronic pain was considered time consuming by 89% of physicians in a single study from West Virginia,44 and in a study from Texas, 65% reported that prescribing continuous release opioids lengthened clinic visits.36 In one study, 21% of participants reported that time constraints and limited staff support was the greatest barrier affecting implementation of patient-provider agreements.34

The main findings of this systematic review are summarized in Figure 2 which highlight physician views on chronic pain and opioids.

|

Figure 2 Factors associated with prescribing opioids for chronic pain (reported by >50% of physicians). |

Discussion

This systematic review provides clinically relevant information and views of physicians who manage and prescribe opioids for chronic pain. Many physicians reported feeling at least somewhat confident or competent prescribing opioids and managing pain. In two studies,25,40 over 80% of respondents reported feeling confident and competent, while a much smaller proportion (19–52%) reported satisfaction treating pain and prescribing opioids. Further research is needed to elucidate how this dissatisfaction affects provider practices (eg prescriptions, care plans, communication, referrals) and to develop interventions to improve provider satisfaction treating chronic pain.

Inadequate training in pain management and opioids was also identified. For example, despite 51–70% of physicians reporting previous training in pain management and opioid prescribing, 54% reported that previous training was inadequate and only 43% reported having good to excellent knowledge about pain management. Other reports describing the associations between physician confidence and training in pain management and opioid prescribing have been mixed. These studies were not included in the systematic review because they included resident physicians and non-physician clinicians. In a study where the Opioid Therapy Provider Survey was completed by a mixed group of 69 clinicians (physicians =56%) attending a pain and opioid focused CME course, clinician confidence in managing chronic pain was not associated with previous training in pain management or mandated opioid-related CME.52 However, in a study that involved 572 primary care physicians and residents-in-training, the intensity of post-residency education about pain management was associated with greater levels of comfort managing chronic pain.53

Our findings suggest that despite perceived confidence, physicians could benefit from ongoing education and training about pain management and opioid prescribing. While one study reported a need for further training in addiction,27 most of the studies in this review did not ask participants about the type of training needed. Because some of the findings suggest good knowledge about adverse events of opioids, additional research is needed to understand the specific training physicians would find beneficial. One study found that the number of CME hours correlated with greater levels of confidence in treating chronic pain.41 Given this finding, voluntary participation in CME activities may be one approach to delivering ongoing pain-related education. The intensity of CME activity may need to be tailored to successfully meet the diverse expectations of individual physicians.

In addition to inherent prescriber characteristics, the results describe several patient and environmental factors that affect the physician. Patient diagnosis and patient satisfaction may play a role in physician decision to prescribe opioids. Physicians were more likely to prescribe opioids to patients with cancer than those with nonmalignant chronic pain. These provider views are in line with recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines that recommend opioids should be avoided for treatment of nonmalignant chronic pain when possible.54 However, the two studies with these findings were published in 2006 and 2011, well before publication of the 2016 CDC guidelines.38,39 Further exploration is needed to understand how physicians perceive pain related to the patient’s diagnosis and whether these perceptions affect care management.

Physicians also reported that concern about regulatory scrutiny and limited resources influenced opioid prescribing practices. Regulatory scrutiny was found to negatively affect opioid prescribing. As regulatory oversight expands with the current opioid epidemic, it is important to understand the intended and unintended consequences on physician behavior.

This review found some factors which were directly reported to affect opioid prescribing but not to the extent anticipated in our original hypothesis. While we suspect that other physician-related factors affect opioid prescribing, more research is needed to specifically examine prescribing patterns of physicians by looking at actual prescription data. Although our conceptual framework was developed to better understand UPOU, the results of this review, which were centered around long-term opioid therapy, could be used to refine key components of the framework (Figure 2).

This review has limitations. The literature search strategy was limited to studies comprised of practicing physicians; thus, the study findings may not represent the opioid prescribing practices of resident physicians or non-physician clinicians. The majority of physician participants were white men greater than 40 years of age who had been in clinical practice greater than 15 years and self-identified as residing in urban areas. Therefore, the findings may not be generalizable beyond the sociodemographic parameters of the study participants. The median response rate to the various surveys was 35% and 3 studies did not report a response rate. The methodological quality of all studies was low. As a result, the study findings may not be fully representative of the opioid prescribing practices of all physicians targeted for recruitment in the 22 studies identified in our literature search. The majority of surveys used in the identified studies were not validated which could jeopardize the accuracy and reproducibility of individual study results. Similarly, the characteristics of physician prescribing practices were assessed and described using a variety of methods, which limited the ability to consistently compare outcomes across studies. Finally, although heroin and illicitly manufactured fentanyl are important public health problems,4 investigating the potential relationships between prescriber characteristics and individual use of illicitly acquired opioids are beyond the scope of this review.

In summary, this systematic review leveraged a conceptual framework to investigate the characteristics of physicians who prescribe long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain. The long-term goal of this area of research is to develop, test, and deploy interventions to mitigate the risks of long-term opioid use. The summary data from this systematic review provides the foundation for the development of prospective studies aimed at further elucidating the constellation of mechanisms that influence physicians who manage pain and prescribe opioids. It is anticipated that the outcomes of future studies will reveal the need for a range of time-dependent interventions to effectively attenuate the various clinician factors that contribute to long-term opioid use.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this study.

References

1. Califf RM, Woodcock J, Ostroff S. A proactive response to prescription opioid abuse. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1480–1485. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr1601307

2. Guy GP

3. Jeffery MM, Hooten WM, Henk HJ, et al. Trends in opioid use in commercially insured and medicare advantage populations in 2007–16: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;362:k2833. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2833

4. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1419–1427. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1

5. Chang HY, Lyapustina T, Rutkow L, et al. Impact of prescription drug monitoring programs and pill mill laws on high-risk opioid prescribers: A comparative interrupted time series analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;165:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.033

6. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Substance Misuse Prevention Media Campaigns. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/capt/tools-learning-resources/prevention-media-campaigns

7. Hooten WM, St Sauver JL, McGree ME, Jacobson DJ, Warner DO. Incidence and risk factors for progression from short-term to episodic or long-term opioid prescribing: A population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:850–856. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.04.012

8. Callinan CE, Neuman MD, Lacy KE, Gabison C, Ashburn MA. The initiation of chronic opioids: a survey of chronic pain patients characterizing chronic opioid use. J Pain. 2017;18:360–365.

9. Stumbo SP, Yarborough BJH, McCarty D, Weisner C, Green CA. Patient-reported pathways to opioid use disorders and pain-related barriers to treatment engagement. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;73:47–54. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2016.11.003

10. Deyo RA, Hallvik SE, Hildebran C, et al. Association between initial opioid prescribing patterns and subsequent long-term use among opioid-naive patients: a statewide retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:21–27. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3810-3

11. Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Bell CM. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:425–430. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1827

12. Clarke H, Soneji N, Ko DT, Yun L, Wijeysundera DN. Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1251. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1251

13. Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1286–1293. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3298

14. Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Characteristics of initial prescription episodes and likelihood of long-term opioid use - United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:265–269. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6610a1

15. Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-prescribing patterns of emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:663–673. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1610524

16. Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:e170504. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504

17. Hooten WM, Brummett CM, Sullivan MD, et al. A conceptual framework for understanding unintended prolonged opioid use. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.10.010

18. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2651

19. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-analyses. Ottawa, ON: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2011. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed May 1, 2018.

20. Brady JE, Giglio R, Keyes KM, DiMaggio C, Li G. Risk markers for fatal and non-fatal prescription drug overdose: a meta-analysis. Inj Epidemiol. 2017;4:24. doi:10.1186/s40621-017-0118-7

21. Herzog R, Alvarez-Pasquin MJ, Diaz C, Del Barrio JL, Estrada JM, Gil A. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:154. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-154

22. Patra J, Bhatia M, Suraweera W, et al. Exposure to second-hand smoke and the risk of tuberculosis in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 observational studies. PLoS Med. 2015;12:

23. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhort G, Pawson R. Development of methodological guidance, publication standards and training materials for realist and meta-narrative reviews: the RAMESES (Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses - Evoling Standards) project. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2014;2:1–278. doi:10.1177/1742395313476901

24. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O, Peacock R. Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: a meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:417–430. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.001

25. MacNeela P, Doyle C, O’Gorman D, Ruane N, McGuire BE. Experiences of chronic low back pain: a meta-ethnography of qualitative research. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9:63–82. doi:10.1080/17437199.2013.840951

26. Sim J, Madden S. Illness experience in fibromyalgia syndrome: a metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:57–67. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.003

27. Snelgrove S, Liossi C. Living with chronic low back pain: a metasynthesis of qualitative research. Chronic Illn. 2013;9:283–301. doi:10.1177/1742395313476901

28. Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, et al. Patients’ experiences of chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain: a qualitative systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e829–e841. doi:10.3399/bjgp13X675412

29. Wong AYL, Forss KS, Jakobsson J, Schoeb V, Kumlien C, Borglin G. Older adult’s experience of chronic low back pain and its implications on their daily life: study protocol of a systematic review of qualitative research. Syst Rev. 2018;7:81. doi:10.1186/s13643-018-0742-5

30. Donovan AK, Wood GJ, Rubio DM, Day HD, Spagnoletti CL. Faculty communication knowledge, attitudes, and skills around chronic non-malignant pain improve with online training. Pain Med. 2016;17:1985–1992. doi:10.1093/pm/pnw029

31. Westanmo A, Marshall P, Jones E, Burns K, Krebs EE. Opioid dose reduction in a VA health care system-implementation of a primary care population-level initiative. Pain Med. 2015;16:1019–1026. doi:10.1111/pme.12699

32. Duensing L, Eksterowicz N, Macario A, Brown M, Stern L, Ogbonnaya A. Patient and physician perceptions of treatment of moderate-to-severe chronic pain with oral opioids. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:1579–1585. doi:10.1185/03007991003783747

33. Franklin GM, Fulton-Kehoe D, Turner JA, Sullivan MD, Wickizer TM. Changes in opioid prescribing for chronic pain in Washington State. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:394–400. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2013.04.120274

34. Kraus CN, Baldwin AT, Curro FA, McAllister RG. Clinical implications of patient-provider agreements in opioid prescribing. Curr Drug Saf. 2015;10:159–164.

35. Macerollo AA, Mack DO, Oza R, Bennett IM, Wallace LS. Academic family medicine physicians’ confidence and comfort with opioid analgesic prescribing for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. J Opioid Manag. 2014;10:255–261. doi:10.5055/jom.2014.0213

36. Nwokeji ED, Rascati KL, Brown CM, Eisenberg A. Influences of attitudes on family physicians’ willingness to prescribe long-acting opioid analgesics for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Clin Ther. 2007;29(Suppl):2589–2602. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.12.007

37. Porucznik CA, Johnson EM, Rolfs RT, Sauer BC. Opioid prescribing knowledge and practices: provider survey following promulgation of guidelines-Utah, 2011. J Opioid Manag. 2013;9:217–224. doi:10.5055/jom.2013.0162

38. Slevin KA, Ashburn MA. Primary care physician opinion survey on FDA opioid risk evaluation and mitigation strategies. J Opioid Manag. 2011;7:109–115.

39. Turk DC, Dansie EJ, Wilson HD, Moskovitz B, Kim M. Physicians’ beliefs and likelihood of prescribing opioid tamper-resistant formulations for chronic noncancer pain patients. Pain Med. 2014;15:625–636. doi:10.1111/pme.12352

40. Wilson HD, Dansie EJ, Kim MS, Moskovitz BL, Chow W, Turk DC. Clinicians’ attitudes and beliefs about opioids survey (CAOS): instrument development and results of a national physician survey. J Pain. 2013;14:613–627. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2013.01.769

41. Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103:738–747. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181e74ede

42. Green CR, Wheeler JR, Marchant B, LaPorte F, Guerrero E. Analysis of the physician variable in pain management. Pain Med. 2001;2:317–327. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4637.2001.01045.x

43. Nishimori M, Kulich RJ, Carwood CM, Okoye V, Kalso E, Ballantyne JC. Successful and unsuccessful outcomes with long-term opioid therapy: a survey of physicians’ opinions. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:50–56. doi:10.1089/jpm.2006.9.50

44. Ponte CD, Johnson-Tribino J. Attitudes and knowledge about pain: an assessment of West Virginia family physicians. Fam Med. 2005;37:477–480.

45. Remster EN, Marx TL. Barriers to managing chronic pain: perspectives of Appalachian providers. Osteopathic Family Physician. 2011;3:141–148. doi:10.1016/j.osfp.2010.07.003

46. Turk DC, Brody MC, Okifuji EA. Physicians’ attitudes and practices regarding the long-term prescribing of opioids for non-cancer pain. Pain. 1994;59:201–208.

47. Wolfert MZ, Gilson AM, Dahl JL, Cleary JF. Opioid analgesics for pain control: wisconsin physicians’ knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and prescribing practices. Pain Med. 2010;11:425–434. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00761.x

48. Bhamb B, Brown D, Hariharan J, Anderson J, Balousek S, Fleming MF. Survey of select practice behaviors by primary care physicians on the use of opioids for chronic pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1859–1865. doi:10.1185/030079906X132398

49. Chen L, Houghton M, Seefeld L, Malarick C, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain: physicians’ attitude and current practice patterns. J Opioid Manag. 2011;7:267–276.

50. Howell D, Kaplan L. Statewide survey of healthcare professionals: management of patients with chronic noncancer pain. J Addict Nurs. 2015;26:86–92. doi:10.1097/JAN.0000000000000075

51. Hwang CS, Turner LW, Kruszewski SP, Kolodny A, Alexander GC. Primary care physicians’ knowledge and attitudes regarding prescription opioid abuse and diversion. Clin J Pain. 2016;32:279–284. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000268

52. Pearson AC, Moman RN, Moeschler SM, Eldrige JS, Hooten WM. Provider confidence in opioid prescribing and chronic pain management: results of the opioid therapy provider survey. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1395–1400. doi:10.2147/JPR.S136478

53. O’Rorke JE, Chen I, Genao I, Panda M, Cykert S. Physicians’ comfort in caring for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Am J Med Sci. 2007;333:93–100.

54. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain–United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315:1624–1645. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.1464

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.