Back to Journals » Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology » Volume 12

Challenges and Solutions in Oral Isotretinoin in Acne: Reflections on 35 Years of Experience

Authors Bettoli V , Guerra-Tapia A , Herane MI, Piquero-Martín J

Received 12 October 2019

Accepted for publication 12 November 2019

Published 30 December 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 943—951

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S234231

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Jeffrey Weinberg

Vincenzo Bettoli,1,2 Aurora Guerra-Tapia,3–5 Maria Isabel Herane,2,5,6 Jaime Piquero-Martín2,5,7

1Department of Clinical Medicine and Oncology, O.U. Dermatology, Teaching Hospital, Azienda Ospedaliera – University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy; 2Member of Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 3Department of Dermatology, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; 4Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain; 5Member of GILEA/GILER (Grupo Ibero-Latinoamericano para el Estudio del Acné/Rosácea; Ibero-Latin American Group for the Study of Acne/Rosacea), Buenos Aires, Argentina; 6Department of Dermatology, Universidad de Chile, Santiago de Chile, Chile; 7Department of Dermatology, Instituto de Biomedicina, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela

Correspondence: Vincenzo Bettoli

Department of Clinical Medicine and Oncology – O.U. of Dermatology -Teaching Hospital, Azienda Ospedaliera – University of Ferrara, Via A.Moro 8, Cona, Ferrara, Italy

Tel +39 335 6588455

Fax +39 05321 4075390

Email [email protected]

Abstract: Acne vulgaris affects more than 80% of adolescents and young adults and forms a substantial proportion of the dermatologist’s and general practitioner’s caseload. Severity of symptoms varies but may result in facial scarring and psychological repercussions. Oral isotretinoin is highly effective but can only be prescribed by specialists. Side effects are recognized and mostly predictable, ranging from cosmetic effects to teratogenicity. These can affect patients’ quality of life and treatment adherence. This article provides a commentary on 4 key areas: the use of oral isotretinoin vs oral antibiotics, including the importance of early recognition of nonresponse to treatment, the psychological effects of acne and isotretinoin treatment, the side effects of isotretinoin therapy, and cosmetic treatment options that can help alleviate predictable side effects. The authors, who have all participated in various international expert groups, draw on relevant literature and their extensive professional experience with oral isotretinoin in the treatment of acne. The aim of this article is to provide an informative and practical approach to managing oral isotretinoin treatment in patients with acne, to help optimize treatment of this skin disease.

Keywords: acne vulgaris, side effect, psychological, cosmetic, management, antibiotic

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is one of the most common skin diseases in Europe,1 and the most common in the USA,2 affecting more than 80% of adolescents and young adults,1 and persisting for decades in many cases.3 It is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit, presenting with symptoms of inflammation – erythema, swelling, discomfort – with scarring reported in 43% of patients.4 As often occurs with dermatological conditions,5 such symptoms have inevitable psychological and social repercussions.6

Treatments vary according to severity, from topical therapy (retinoids, benzoyl peroxide, antibiotics) in mild cases to oral antibiotics, hormonal treatments, and oral isotretinoin in moderate to severe cases. Current European guidelines7 strongly recommend the use of oral isotretinoin -in moderate or severe papulopustular/nodular acne, at a dose of 0.3–0.5 mg/kg/day, and acne conglobata, at a dose of ≥ 0.5 mg/kg/day. Systemic therapy, including isotretinoin, is not usually recommended for mild-to-moderate papulopustular acne.7,8

Early reported side effects of oral isotretinoin9,10 appeared alarming and probably influenced prescribing habits. Despite more recent studies and reviews showing a good safety profile,11 there may be some persistent reluctance to prescribe the drug. Yet a delay in adequate treatment of acne can lead to physical scarring and affect quality of life – a balance must be struck to avoid undertreatment of this highly prevalent condition.

We describe our experience of oral isotretinoin use in patients with acne vulgaris, drawing on relevant publications to address key points relating to isotretinoin use, namely: the use of oral isotretinoin vs antibiotics, the psychological effects of acne and oral isotretinoin treatment, the side effects of oral isotretinoin treatment, and cosmetic approaches that can be used concurrently to alleviate predictable side effects.

Use of Isotretinoin vs Antibiotics

Management of acne vulgaris should aim to treat all factors involved: abnormal follicular keratinization, sebum production, bacterial flora, and especially inflammation. Patients should be offered a simple treatment regimen to increase acceptability and adherence.12

Oral antibiotics are generally used to treat moderate to severe acne; they should be used along with a topical treatment,13 preferably containing benzoyl peroxide.14 In recent years, the exponential increase in antibiotic resistance has led to limitations on the use of antibiotics – oral antibiotics should be used for no longer than 3 months15 – and appropriate alternatives are required.16 One alternative is oral isotretinoin,17 which has led the management of severe acne since Peck reported complete clearance in 13 of 14 patients treated.18 Traditionally, it has been used in the management of acne that meets the following criteria:

- Severe nodulocystic acne

- Severe papulopustular acne

- Moderate to severe nodular acne

- Minimal response to previous treatments

- Prone to significant scarring

- Sudden relapse after stopping therapy

- Patients with significant psychological distress

More recently, the use of oral isotretinoin has been extended to include moderate inflammatory acne with resulting physical or psychological scarring. Low-dose isotretinoin is effective in the control of hyperseborrhea and moderate inflammatory acne that does not respond to systemic antibiotics as a consequence of acquired resistance.

Early recognition of failure to respond to antibiotics is important.19 Nagler and colleagues carried out a clinical study at the University of New York, in 137 patients who received oral isotretinoin between 2005 and 2014, looking at systemic antibiotic use in these patients prior to isotretinoin. They reported a mean duration of antibiotic therapy of 331.3 days; 15% of antibiotics were prescribed for 3 months or less, 64% for 6 months or more, and 34% for 1 year or longer. The study concluded on the importance of early recognition of patients with failure to respond to oral antibiotics, urging a decision at 6 to 8 weeks to continue or discontinue antibiotics and consider isotretinoin.20

Our Experience and Recommendations

For 30 years, we (Piquero et al)21 have been using isotretinoin at low doses or 0.2–0.3 mg/kg/day for a period of 12 months, then maintaining with topical therapy, with an excellent response in more than 80%, in moderate inflammatory acne in patients prone to physical or psychological scarring. In severe inflammatory acne, we continue to use the doses recommended in international guidelines. Based on the evidence and on our experience, patients should be offered a simple treatment regimen to increase acceptability and adherence. The indication for and duration of systemic antibiotics should be limited, particularly when effective alternatives are available.22

Psychological Aspects of Acne Vulgaris and the Role of Oral Isotretinoin

Acne has a substantial psychological impact on most patients with the condition, manifesting mainly as depressive symptoms.23,24 Oral isotretinoin treatment has had the greatest therapeutic impact on acne, improving symptoms markedly. However, a study published in 1983 asserted that oral isotretinoin could cause depressive symptoms,9 and since then multiple publications have fueled controversy on this subject. Those that found a positive association between isotretinoin and depression concluded that it was an idiosyncratic effect occurring in a minority of patients, who often had a past history or family history of depression.25,26 However, most studies have not found an association between oral isotretinoin and depression, but rather, have found a beneficial effect of reduced depressive symptoms with the treatment.27–32

In 2017, a systematic review and meta-analysis was published on the association between oral isotretinoin and depression.33 It included 31 controlled or prospective non-controlled studies with ≥ 15 patients who had received oral isotretinoin for acne. With these criteria, the authors evaluated data from 2939 patients. The scores on the multiple depression scales used before and at the end of treatment did not show a significant increase in depressive symptoms in patients treated with isotretinoin compared with those on other treatments. Rather, the scores that were close to indicating depression decreased significantly in patients treated with isotretinoin after completing treatment, and this improvement began when treatment began.

In 2004, we (Guerra-Tapia and colleagues)34 developed a questionnaire on treatment satisfaction, which included an evaluation with depression and anxiety scales before, during, and after isotretinoin treatment. The questionnaire was delivered to approximately 4000 patients. All of the respondents reported substantial psychological benefits, giving high satisfaction scores for oral isotretinoin treatment. All said they would be willing to repeat the treatment if necessary in the future.34

Our Experience and Recommendations

Treatment of acne with oral isotretinoin does not appear to be associated with increased depression for the majority of patients; in fact, it appears to be associated with a reduction in depressive symptoms.11 There will be a small subset of patients who have increased depression and suicidal thoughts while on this medication. With this in mind, and given the increased predisposition - independently of other factors - to depression during adolescence, it would be prudent to recommend close monitoring of all patients with acne, to identify those who, due to individual susceptibility, have a high risk of depression.

Side Effects of Oral Isotretinoin

Isotretinoin is a physiologically active metabolite of vitamin A (retinol).35 Almost all patients treated with oral isotretinoin experience disease clearance,7,9 but at therapeutic doses, it can have side effects. Most, with the exception of teratogenicity, are dose-related. A recent Cochrane review36 of 31 randomized control trials involving 3836 participants concluded that non-serious side effects were more common in isotretinoin than oral antibiotics plus topical agent, but no conclusion was drawn on serious adverse events due to the low number of events.

Oral isotretinoin should only be prescribed under the supervision of physicians with expertise in the use of systemic retinoids for the treatment of acne and with a full understanding of the risks and monitoring requirements. General practitioners may also be consulted by patients during their isotretinoin treatment, so awareness of relevant issues is advantageous.

Side effects may be categorized as: 1) teratogenic, 2) clinical: cutaneous or extracutaneous, and 3) laboratory findings. Oral isotretinoin has also been associated with nonspecific side effects involving various body systems, but generally these are sporadic or isolated descriptions whose clinical relevance appears to not be significant compared to the huge amount of prescriptions issued worldwide. In addition, it is likely that there is a tendency to overestimate the incidence and severity of side effects in the information sheets of oral isotretinoin, as frequently happens with other drugs.37

Teratogenicity

This is the most important side effect.38 Ingestion of oral isotretinoin in female patients of childbearing potential, independently of the dose, may induce major fetal malformations, premature birth, or spontaneous abortion in a high percentage of cases. Pregnancy prevention programs (PPPs), in their various forms,39,40 have generally proved successful to an extent, as unplanned pregnancies while on treatment with oral isotretinoin still occur, albeit in small numbers. Female patients undergo laboratory pregnancy testing before starting treatment, then monthly at the beginning of each menstrual cycle during treatment, and one month after finishing treatment. They receive detailed verbal and written information on isotretinoin treatment in general and contraception methods in particular. Contraception use must begin one month before starting treatment and continue throughout treatment until one month after stopping treatment. Unfortunately, there is some initial evidence to suggest that even the most stringent PPPs, like iPLEDGE, the system currently used in the USA, do not decrease the number of fetal exposures to oral isotretinoin in comparison with previous, less stringent PPPs.41 Consequently, it is extremely important to ensure patients receive accurate information and remain in close contact with their specialist. Furthermore, two recent articles have highlighted the potential unintended barriers that such stringent compulsory programs can have, and indeed the potential effect of delay to starting treatment or premature stopping treatment in some cases, particularly in certain population groups, due to the inconvenient nature of the programs.42,43 In 2018, the European Medicines Agency completed its review of retinoid medicines and confirmed that an update of pregnancy prevention measures was needed.44

Cutaneous Side Effects

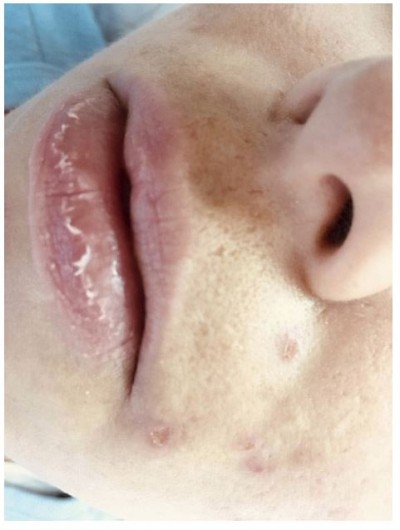

Side effects such as dryness and desquamation of the skin and mucous membranes are very frequent; indeed, their absence may raise the question of under-dosing. They occur secondary to a pharmacologically-induced sebum-suppressive effect45 and epidermal dyscohesion46,47 that results in xerotic and desquamative changes.45–47 The most common clinical side effect is cheilitis (Figure 1), a dryness of the lips that may range from simple xerosis to painful fissures.48 Dry skin and desquamation are frequently experienced in a dose-dependent manner where sebaceous glands are most prevalent, namely the face, chest, and back. Dryness of the nose and eyes may also be seen when patients receive a dose that is too high for them. Severe skin reactions (eg erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis) have very rarely been observed.49 Some patients experience an initial worsening of their acne in the first month of treatment; less commonly, isotretinoin can induce acne fulminans.50 This is probably related to a dose of isotretinoin too high for that individual patient.

|

Figure 1 Side effects of oral isotretinoin treatment. Cheilitis, dry skin, impetigo lesions and melasma. Image courtesy of MI Herane. |

Extracutaneous Side Effects

Headache, tiredness, and eye disorders including visual disturbances at night, keratitis, and corneal opacities, may be experienced during treatment and can sometimes be drug-related and dose-related. Benign intracranial hypertension has been reported when isotretinoin has been used together with certain antibiotics.51 Gastrointestinal disorders associated with colitis and inflammatory bowel disease may occur during treatment with isotretinoin, but a causal relationship has not been demonstrated.52,53 Indeed, meta-analyses have found no association between increased risk of IBD and isotretinoin use.54 The psychiatric effects of oral isotretinoin are discussed elsewhere in this article.

Laboratory Abnormalities

Lipids: oral isotretinoin may induce a dose-related increase in blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels. A large meta-analysis review53 of this topic found that oral isotretinoin was associated with a statistically significant change in the mean value of these parameters, but the mean increase did not meet criteria to be considered high risk. In addition, the proportion of patients with such laboratory abnormalities was low enough that it was deemed not necessary to check this on a monthly basis (as stated in the EU summary of product characteristics55) but rather to check before starting treatment, after 6 weeks, and subsequently every 3 months during therapy.56 Oral isotretinoin should be discontinued if hypertriglyceridemia cannot be controlled.

Liver transaminases may also increase while on treatment, with a clearly dose-dependent effect. It should be borne in mind that there are many possible causes for elevated transaminases, and these should be excluded. In a recent review, the increase in transaminases due to oral isotretinoin was defined as transient and not typically requiring discontinuation of the treatment.57 Transaminases should be checked before treatment, after 6 weeks, and subsequently at 3 monthly intervals unless more frequent monitoring is clinically indicated.

Creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) is a muscle enzyme that is physiologically increased by exercise. Oral isotretinoin has been considered a further possible inducer, and the effect may be dose-dependent. There are few clinical studies on CPK and oral isotretinoin, and most of the published articles are case reports.58 The prevalence of increased CPK levels ranges between 10% and 50%58 but the causative role of the drug should be assessed on a case by case basis. Moderate physical exercise, as many adolescents do, is a well-known cause of elevated CPK levels. Muscle symptoms are occasionally reported, and very rarely evidence of muscle damage has been recorded.10,58 Bone changes have occasionally occurred after several years of administration at very high doses in patients affected by disorders of keratinization or pediatric cancers, although the dose, duration of treatment, and total cumulative dose in these patients generally far exceeded those recommended for the treatment of acne.59–62

Monitoring for full blood count abnormalities is of low value, as abnormalities occur infrequently and are unlikely to affect management.63

Our Experience and Recommendations

Appropriate management of the dosage is critical. Each patient has unique characteristics in terms of drug absorption, bioavailability, and presentation of side effects. Dermatologists must keep in mind the differences in the production of the active agent, and the wide-spread use of oral isotretinoin generics available.

The literature clearly shows that a low starting daily dose of 0.1–0.2 mg/kg/day, or around 10 mg daily, and a progressive increase to the highest dose tolerated by the patient is a successful way to get good clinical results while minimizing side effects in comparison with a standard dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day.64

All drugs have the potential to cause side effects. Clearly, the balance between positive clinical effects and side effects must be weighted towards the first, and this is indeed the case in the vast majority of patients treated with oral isotretinoin. A review of the efficacy and adverse events of oral isotretinoin, including only randomized control trials, with a total of 760 patients, found that only 12 patients stopped treatment because of side effects.49

Oral isotretinoin is undoubtedly the most effective drug in the management of severe acne that is refractory to other therapies. It is sometimes erroneously described in broad brush-strokes as a dangerous drug, without specifying that the only real aspect of concern is teratogenicity in female patients of childbearing age, for which risk management plans are in place, as described above. Until the discovery of new active anti-acne molecules, oral isotretinoin remains the drug on which to focus and accumulate further expertise in the treatment of severe acne.

Cosmetic Issues

The cosmetic management of acne is of great importance and should be viewed as part of the treatment recommendations in patients treated with topical and oral products.65 Naturally, patients want good therapeutic results in the shortest time possible. Oral isotretinoin, which is so useful in the management of inflammatory acne, alters the barrier function of skin, sebaceous lipids, and skin microflora. Appropriate advice and cosmetic treatment help to diminish the adverse effects, thus favoring adherence to treatment, which contributes to better therapeutic efficacy and quality of life for patients.66 In dermatology in general, and especially in acne, dermocosmetics have a very important role in minimizing the adverse effects of pharmacological treatment.67

Adherence to prescribed treatment has a large impact on treatment outcome. Multiple studies have shown that adherence to acne medications is particularly low and is associated with a suboptimal response to treatment, particularly when an individual is prescribed a combination of topical and systemic treatments.3,68 It is important to add dermocosmetics at the start of oral isotretinoin treatment to minimize side effects and improve adherence. They should be chosen according to their ingredients, to align with the specific needs of the patient and their environment. Oral isotretinoin is associated with the following structural and functional changes in the skin:46,69

Altered Barrier Function

Xerosis, fissures, and eczematous dermatitis are common side effects due to altered barrier function. As a consequence, there is loss of the homeostatic control of water content and flux (barrier permeability), low recognition and neutralization of microbes (antimicrobial barrier) and loss of the antioxidant barrier. Consequently, there is increased risk with solar exposure (photoprotection barrier) and altered response to exogenous allergens and haptens (immune barrier).46

Corneocyte Decohesion

Oral isotretinoin causes an increase in epidermal turnover and skin fragility, making it susceptible to intradermal separation. There is loss of desmosomes and reduced tonofibrils. Corneocytes are easily separated from the most external layer of the stratum corneum, which explains the desquamation experienced by patients, and transepidermal water loss (TEWL) may increase, depending on the oral isotretinoin dose.70 The changes trigger a cycle of pro-inflammatory cytokine release that causes epidermal hyperproliferation and hyperkeratosis.46,71

In 2007, we (Herane and colleagues) conducted a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled study72 of an adjuvant therapy to oral isotretinoin (0.4–0.7 mg/kg) with a specific moisturizing gel-cream formulated with actives including biosaccharide gum-2, hyaluronic acid and glycerin. After one month of treatment, compared to the placebo group, the group treated with the adjuvant had 19% higher hydration levels and lower TEWL levels (barrier effect) than those on isotretinoin alone.

Changes in Cutaneous Lipids

It is important to differentiate between lipids that are physiologically integrated in the intercellular lipid membrane (ILM) and those derived from sebum that are secreted in the follicular canal and flow to the skin surface. Studies in mice showed that isotretinoin did not alter the ILM.46,70 The sebum-suppressive effect of oral isotretinoin (at a recommended total dose of 100–120 mg/kg) begins after one month of treatment and subsides around 4–5 months after completing treatment. At 6 weeks, the change in lipid composition begins, with a reduction in the proportion of glycerides (by 36%), increase in free sterols (34%) and total ceramides (19%), and increase in the free sterol: cholesterol ratio (86%).73 Cholesterol increases 10–25% and the proportion of waxy esters and squalene decreases.45,46 This translates to a reduction in comedogenesis and number of comedones.71,74

Skin Microflora

Oral isotretinoin induces changes in the type and number of microorganisms that colonize the skin and anterior nasal mucosa, with increased colonization by Staphylococcus aureus and a marked reduction in Propionibacterium acnes from the start of treatment that continues after treatment ends.75

Our Experience and Recommendations

Appropriate skin care in acne vulgaris treated with retinoids involves gentle cleansing, repair of the cutaneous barrier and maintenance of barrier function.72 Cleansing should use gentle soaps, cleansing emulsions or micellar cleansing lotions.66 Abrasive cleansers and those containing sulfur, glycolic acid, or similar, should be avoided. Hydrating and emollient products should be noncomedogenic, hypoallergenic, non-irritating, and non-greasy, with an aqueous base.76 It is highly important to use specific moisturizers that contain active ingredients of a sufficient quality and concentration to protect and repair the skin. Products with hyaluronic acid, glycerin, biosaccharides, oligosaccharides, or similar, are suitable.72,77

During periods of high solar exposure and particularly in countries with thinning of the ozone layer, dermatitis, eczema, cheilitis, and other signs of solar sensitivity are common in photoexposed areas: mainly the face, hands and arms. An SPF 50+ UVA/UVB solar protector that has been specifically tested for comedogenicity in oily, acne-prone skin, should be used when exposed to sun, reapplied every 2 hrs and after swimming or sweating.

For the lips and mucous membranes, petroleum jelly at night and lip balms with an SPF 30–50 filter during the day, reapplied several times per day, are recommended. Eye drops and gels are particularly helpful for patients who wear contact lenses or live in areas with high air pollution levels. Sunglasses should be worn, especially in summer and if taking part in any outdoor activities.

Regarding hair removal, cold waxes or razors are preferable to hot waxing or lasers, and moisturizer and sun protection should be applied afterwards. Intensive pulsed light (IPL) hair removal can be performed with caution.

Peeling treatments should be reserved for scarring and residual marks once treatment is completed. There is controversy regarding this and procedures such as elective surgery, dermabrasion, chemical abrasives, CO2 laser, and fractionated radiofrequency: some practitioners delay such procedures until more than 6 months55 after stopping oral isotretinoin, and others wait 20 to 30 days, the normal time required for the drug to be eliminated. Two recent reviews78,79 concluded that mechanical dermabrasion and fully ablative laser were not recommended,78 but that there was insufficient evidence to delay manual or microdermabrasion, superficial chemical peels, cutaneous surgery, fractional ablative and fractional nonablative laser resurfacing for patients currently or recently (6–12 months) exposed to isotretinoin.78,79 Our current practice is to wait for around 2 months after stopping isotretinoin before starting such procedures.

In summary, use of specific cosmetic adjuvant treatments increases compliance with topical and oral pharmacological treatments 2.2-fold with a clear reduction in the number and severity of inflammatory lesions and a reduction in adverse effects.66

Conclusions

Acne has a substantial psychological impact, frequently manifesting as depressive symptoms. Timely, effective treatment not only helps minimize risk of permanent physical scarring, but helps with psychological aspects, and such improvement in quality of life is appreciated by patients. Appropriate cosmetic advice and treatments should be considered alongside pharmacological treatment to diminish the adverse effects and encourage adherence to treatment, thus improving outcomes. Oral isotretinoin represents a milestone in the treatment of acne; it really has changed patients’ lives. The most serious side effect is teratogenicity, so adherence to existing pregnancy prevention programs is paramount, regardless of the isotretinoin dose. Other side effects, in the vast majority of the cases can be easily prevented and/or treated. Oral isotretinoin, appropriately managed, may be considered a reasonable alternative in cases of acne that fails to respond to therapies such as antibiotics.

Acknowledgements

ISDIN Spain funded the publication costs of this article.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

MIH has been a speaker for Galderma, and has participated in investigations for Galderma, Isdin, and La Roche Posay. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Bhate K, Williams HC. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(3):474–485. doi:10.1111/bjd.2013.168.issue-3

2. American Academy of Dermatology [Website]. Available from: https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/acne#overview.

3. Dréno B, Layton A, Zouboulis CC, et al. Adult female acne: a new paradigm. JEADV. 2013;27:1063–1070. doi:10.1111/jdv.12061

4. Tan J, Kang S, Leyden J. Prevalence and Risk factors of acne scarring among patients consulting dermatologists in the USA. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(2):97–102.

5. Dalgard F, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(4):984–991. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.530

6. Guerra-Tapia A, Asensio Martínez Á, García Campayo J. The emotional impact of skin diseases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106(9):699–702. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2015.06.002

7. Nast A, Dreno B, Bettoli V, et al. European Evidence-based (S3) guideline for the treatment of acne – update 2016. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1261. doi:10.1111/jdv.13776

8. Thiboutot D, Dreno B, Abanmi A, et al. Practical management of acne for clinicians: an international consensus from the global alliance to improve outcomes in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:S1–S23. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.078

9. Hazen PG, Carney JF, Walker AE, Stewart JJ. Depression–a side effect of 13-cis-retinoic acid therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9(2):278–279. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(83)80154-6

10. Hodak E, Gadoth N, David M, Sandbank M. Muscle damage induced by isotretinoin. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293(6544):425–426. doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6544.425

11. Li C, Chen J, Wang W, Ai M, Zhang Q, Kuang L. Use of isotretinoin and risk of depression in patients with acne: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e021549. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021549

12. Asai Y, Baibergenova A, Dutil M, et al. Management of acne: Canadian clinical practice guideline. CMAJ. 2016;188(2):118–126. doi:10.1503/cmaj.140665

13. Ribera M, Guerra A, Moreno-Giménez JC, de Lucas R, Pérez-López M. Treatment of acne in daily clinical practice: an opinion poll among Spanish dermatologists. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102(2):121–131. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2010.07.003

14. Guerra-Tapia A. Effects of benzoyl peroxide 5% clindamycin combination gel versus adapalene 0.1% on quality of life in patients with mild to moderate acne vulgaris: a randomized single-blind study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(6):714–722.

15. Zouboulis CC, Piquero-Martin J. Update and future of systemic acne treatment. Dermatology. 2003;206:37–53. doi:10.1159/000067821

16. Dréno B. Bacteriological resistance in acne: a call to action. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26(2):127–132. doi:10.1684/ejd.2015.2685

17. Herane MI. Resistencia bacteriana. In: Kaminsky A y Flórez-White M; cols, editors. Acne: Un Enfoque Global.

18. Peck GL, Olsen TG, Yoder FW, et al. Prolonged remissions of cystic and conglobate acne with 13 cis retinoic acid. N Engl J Med. 1979;300(7):329–333. doi:10.1056/NEJM197902153000701

19. Ozolins M, Eady EA, Avery A, et al. Randomised controlled multiple treatment comparison to provide a cost-effectiveness rationale for the selection of antimicrobial therapy in acne. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9(1):iii–212. doi:10.3310/hta9010

20. Nagler AR, Milam EC, Orlow SJ. The use of oral antibiotics before isotretinoin therapy in patients with acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:273–279. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.046

21. Piquero-Martin J, Misticone S, Piquero-Casals V, Piquero-Casals J. Topic therapy-mini isotretinoin doses vs topic therapy-systemic antibiotics in the moderate acne patients. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2002;129:S382.

22. Barbieri JS, Bhate K, Hartnett KP, et al. Trend in oral antibiotic prescription in dermatology, 2008 to 2016. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:290. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4944

23. Guerra Tapia A, Camacho FM. Aspectos psíquicos del acné. Influencia Terapéutica. Monogr Dermatol. 2008;21:11–123.

24. Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(5):846–850. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02511.x

25. Azoulay L, Blais L, Koren G, LeLorier J, Bérard A. Isotretinoin and the risk of depression in patients with acne vulgaris: a case-crossover study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):526–532. doi:10.4088/JCP.v69n0403

26. Bremner JD, Shearer KD, McCaffery PJ. Retinoic acid and affective disorders: the evidence for an association. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):37–50. doi:10.4088/JCP.10r05993

27. Kaymak Y, Kalay M, Ilter N, Taner E. Incidence of depression related to isotretinoin treatment in 100 acne vulgaris patients. Psychol Rep. 2006;99(3):897–906. doi:10.2466/PR0.99.7.897-906

28. Strahan JE, Raimer S. Isotretinoin and the controversy of psychiatric adverse effects. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(7):789–799. doi:10.1111/ijd.2006.45.issue-7

29. Marqueling AL, Zane LT. Depression and suicidal behavior in acne patients treated with isotretinoin: a systematic review. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26(4):210–220. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2008.03.005

30. Hahm BJ, Min SU, Yoon MY, et al. Changes of psychiatric parameters and their relationships by oral isotretinoin in acne patients. J Dermatol. 2009;36(5):255–261. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00635.x

31. Gnanaraj P, Karthikeyan S, Narasimhan M, Rajagopalan V. Decrease in “Hamilton rating scale for depression” following isotretinoin therapy in acne: an open-label prospective study. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60(5):461–464. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.164358

32. Singer S, Tkachenko E, Sharma P, Barbieri J, Mostaghimi A. Psychiatric adverse events in patients taking isotretinoin as reported in a food and drug administration database from 1997 to 2017. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;3.

33. Huang YC, Cheng YC. Isotretinoin treatment for acne and risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(6):1068–1076.e9. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.028

34. Alomar A, Guerra Tapia A, Perulero N, Badía X, Canals L, Álvarez C. Desarrollo de un cuestionario de evaluación de la satisfacción con el tratamiento en pacientes con acné. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2004;95(8):491–495. (). doi:10.1016/S0001-7310(04)76865-9

35. Cañete A, Cano E, Muñoz-Chápuli R, Carmona R. Role of vitamin A/retinoic acid in regulation of embryonic and adult hematopoiesis. Nutrients. 2017;9(2):159. doi:10.3390/nu9020159

36. Costa CS, Bagatin E, Martimbianco ALC, et al. Oral isotretinoin for acne (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:

37. Sonthalia S, Sahaya K, Arora R, et al. Nocebo effect in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81(3):242–250. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.155573

38. Holst H, Muhari-stark E, Lava SA. Teratogenicity of systemic isotretinoin. Minerva Pediatr. 2018;70:107.

39. Kowitvanichkanont T, Driscoll T. A comparative review of the isotretinoin pregnancy risk management programs across four continents. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(9):1035–1046. doi:10.1111/ijd.13950

40. Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, et al. Oral isotretinoin and pregnancy prevention programmes. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:466. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10686.x

41. Shin J, Cheettham TC, Wong L, et al. The impact of the iPLEDGE program on isotretinoin fetal exposure in an integrated health care system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1117. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.09.017

42. Mori WS, Houston N, Moreau JF, et al. Personal burden of isotretinoin therapy and willingness to pay for electronic follow-up visits. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(3):338–340. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.4763

43. Charrow A, Xia FD, Lu J, Waul M, Joyce C, Mostaghimi A. Differences in isotretinoin start, interruption, and early termination across race and sex in the iPLEDGE era. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0210445. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0210445

44. European Medicines Agency. Updated measures for pregnancy prevention during retinoid use. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/medicines/human/referrals/retinoid-containing-medicinal-products.

45. Ward A, Brogden RN, Heel RC, Speight TM, Avery GS. Isotretinoin. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in acne and other skin disorders. Drugs. 1984;28(1):6–37. doi:10.2165/00003495-198428010-00002

46. Del Rosso JQ. Clinical relevance of skin barrier changes associated with the use of oral isotretinoin: the importance of barrier repair therapy in patient management. J Drug Dermatol. 2013;12:626.

47. Elias PM. Epidermal effects of retinoids: supramolecular observations and clinical implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(4 Pt 2):797–809. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(86)70236-3

48. Ornelas J, Rosamilia L, Larsen L, et al. Objective assessment of isotretinoin-associated cheilitis: isotretinoin Cheilitis Grading Scale. J Dermatol Treat. 2016;27:153. doi:10.3109/09546634.2015.1086477

49. Vallerand IA, Lewinson RT, Farris MS, et al. Effficacy and adverse events of oral isotretinoin for acne: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:76. doi:10.1111/bjd.15668

50. Brelsford M, Beute TC. Preventing and managing the side effects of isotretinoin. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008;27(3):197–206. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2008.07.002

51. Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1(3):162–169. doi:10.4161/derm.1.3.9364

52. Crockett SD, Porter CQ, Martin CF, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD. Isotretinoin use and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(9):1986–1993. doi:10.1038/ajg.2010.124

53. Lee SY, Jamal MM, Nguyen ET, Bechtold ML, Nguyen DL. Does exposure to isotretinoin increase the risk for the development of inflammatory bowel disease? A meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:210. doi:10.1097/MEG.0000000000000496

54. Etminan M, Bird ST, Delaney JA, Bressler B, Brophy JM. Isotretinoin and risk for inflammatory bowel disease: a nested case-control study and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(2):216–220. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.1344

55. Roche. Summary of product characteristics, isotretinoin 10 mg capsules. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1114/smpc.

56. Lee YH, Scharnitz TP, Muscat J, Chen A, Gupta-Elera G, Kirby JS. Laboratory monitoring during isotretinoin therapy for acne: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:35. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3091

57. Bauer LB, Ornelas JN, Elston DM, Alikhan A. Isotretinoin: controversies, facts, and recommendations. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9:1435. doi:10.1080/17512433.2016.1213629

58. Kaymak Y. Creatine phosphokinase values during isotretinoin treatment for acne. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:398. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03491.x

59. DiGiovanna JJ. Isotretinoin effects on bone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(5):S176–82. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.113721

60. DiGiovanna JJ, Langman CB, Tschen EH, et al. Effect of a single course of isotretinoin therapy on bone mineral density in adolescent patients with severe, recalcitrant, nodular acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(5):709–717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.04.032

61. Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. High-dose treatment with vitamin A analogues and risk of fractures. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(5):478–482. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.59

62. Kocijancic M

63. Barbieri JS, Shin DB, Wang S, Margolis DJ, Takeshita J. The clinical utility of laboratory monitoring during isotretinoin therapy for acne and changes to monitoring practices over time. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.025

64. Borghi A, Mantovani L, Minghetti S, Virgili A, Bettoli V. Acute acne flare following isotretinoin administration: potential protective role of low starting dose. Dermatology. 2009;218:178. doi:10.1159/000182270

65. González Guerra E, Guerra Tapia A. Application of cosmeceuticals to dermatological practice. Monogr Dermatol. 2012;25:63–67.

66. De Lucas R, Moreno-Arias G, Pérez-López M, et al. Adherence to drug treatments and adjuvant barrier repair therapies are key factors for clinical improvement in mild to moderate acne: the ACTUO observational prospective multicenter cohort trial in 643 patients. BMC Dermatol. 2015;15:17. doi:10.1186/s12895-015-0036-8

67. Araviiskaia E, Dréno B. The role of topical dermocosmetics in acne vulgaris. JEADV. 2016;30:926–935. doi:10.1111/jdv.13579

68. Mc Donald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288:2868–2879. doi:10.1001/jama.288.22.2868

69. Dall’oglio F, Tedeschi A, Fabbrocini G, Veraldi S, Picardo M, Micali G. Cosmetics for acne: indications and recommendations for an evidence-based approach. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2015;150(1):1–11.

70. Elias PM, Fritsch PO, Lampe M, et al. Retinoid effects on epidermal structure, differentiation, and permeability. Lab Invest. 1981;44(6):531–540.

71. Del Rosso JQ, Levin J. The clinical relevance of maintaining the functional integrity of the stratum corneum in both healthy and diseased skin. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4(9):22–42.

72. Herane MI, Fuenzalida H, Zegpi E, et al. Specific gel-cream as adjuvant to oral isotretinoin improved hydration and prevented TEWL increase-a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Cosm Dermatol. 2009;8:181–185. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2009.00455.x

73. Melnik B, Kinner T, Plewig G. influence of oral isotretinoin treatment on the composition of comedonal lipids: implications for comedogenesis in acne vulgaris. Arch Dermatol Res. 1988;280(2):97–102. doi:10.1007/BF00417712

74. Greene RS, Downing DT, Pochi PE, et al. Anatomical variation in the amount and composition of human skin surface lipid. J Invest Dermatol. 1970;54(3):240–247. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12280318

75. Basak PY, Cetin ES, Gurses I, et al. The effects of systemic isotretinoin and antibiotic therapy on the microbial floras in patients with acne vulgaris. JEADV. 2013;273:332–336.

76. Ch L G, Nopakun N, Micali G, et al. Meeting the challenges of acne treatment in Asian patients: a review of the role of dermocosmetics as adjunctive therapy. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2016;9:85–92. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.184043

77. Capitanio B, Sinagra JL, Weller RB, et al. Randomized controlled study of a cosmetic treatment for mild acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(4):346–349. doi:10.1111/ced.2012.37.issue-4

78. Spring LK, Krakowski AC, Alam M, et al. Isotretinoin and timing of procedural interventions: a systematic review with consensus recommendations. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(8):802–809. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2077

79. Waldman A, Bolotin D, Arndt KA, et al. ASDS guidelines task force: consensus recommendations regarding the safety of lasers, dermabrasion, chemical peels, energy devices, and skin surgery during and after isotretinoin use. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(10):1249–1262. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001166

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.