Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Care Need Combinations for Dementia Patients with Multiple Chronic Diseases

Authors Jhang KM, Wang WF, Cheng YC, Tung YC, Yen SW, Wu HH

Received 1 September 2022

Accepted for publication 30 December 2022

Published 19 January 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 179—195

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S388394

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Kai-Ming Jhang,1,* Wen-Fu Wang,1,2,* Yu-Ching Cheng,3,* Yu-Chun Tung,4,* Shao-Wei Yen,5 Hsin-Hung Wu3,6,7

1Department of Neurology, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan; 2Department of Holistic Wellness, Ming Dao University, Changhua, Taiwan; 3Department of Business Administration, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, Taiwan; 4Department of Pharmacy, Taichung Veterans General Hospital Puli Branch, Nantou, Taiwan; 5Department of Information Management, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, Taiwan; 6Department of M-Commerce and Multimedia Applications, Asia University, Taichung City, Taiwan; 7Faculty of Education, State University of Malang, Malang, East Java, Indonesia

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Hsin-Hung Wu, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to find care need combinations for dementia patients with multiple chronic diseases and their caregivers.

Patients and Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted with 83 patients who had multiple chronic diseases. Variables from patients included age, gender, severity of clinical dementia rating, feeding, hypnotics, mobility, getting lost, mood symptoms, and behavioral and psychological symptoms. Moreover, 26 types of care needs were included in this study. The Apriori algorithm was employed to first identify care need combinations and then to find the relationships between care needs and variables from dementia patients with multiple chronic diseases.

Results: Six rules were generated for care need combinations. Four care needs could be formed as a basic care need bundle. Moreover, two additional care needs could be added to provide a wider coverage for patients. In the second stage, 93 rules were found and categorized into three groups, including 2, 6, and 28 general rules with support of 30% but less than 40%, 20% but less than 30%, and 10% but less than 20%, respectively. When the support value is 10% but less than 20%, more variables from patients were found in rules which help the dementia collaborative care team members provide tailor-made care need bundles.

Conclusion: Four basic care needs were social resources referral and legal support (Care (1)), drug knowledge education (Care (3)), memory problem care (Care (5)), and fall prevention (Care (8)). Besides, disease knowledge education (Care (2)) and hypertension care (Care (16)) were frequent unmet needs in this specific population. Moreover, care for the mood of the caregiver (Care (11)) should be considered especially in dementia patients with preserved ambulatory function or with symptoms of hallucination. The collaborative care team should pay more attention to those care needs when assessing this specific population.

Keywords: multiple chronic diseases, care need, dementia, dementia collaborative care team, Apriori algorithm

Introduction

Population aging is happening worldwide. By 2030, Asia will contain up to 60% of the world’s older adults aged 60 years or above and 50% of the world’s oldest-old.1 The number of older people in Taiwan has grown rapidly in the past decades, with the percentage of the population over the age of 65 years increasing from 6.8% in 1992 to 16.9% in 2022.2 Dementia is a neurodegenerative illness strongly associated with aging. The prevalence of all-cause dementia and mild cognitive impairment were 8.04% and 18.76%, respectively, in Taiwanese people aged 65 years or above in 2013.3 Dementia is still incurable; therefore, appropriate care intervention to satisfy the unmet needs of people living with dementia (PLWD) and their caregivers is important.4,5

Black et al6 found that more than 95% of PLWD and caregivers have one or more unmet needs. The most common needs for PLWD were safety needs, meaningful activities, legal issues/concerns, and nursing or pharmacological treatment and care. On the other hand, the most common needs for caregivers were memory disorder education, care skills and knowledge of resources, caregiver’s mental health, and access to informal support.6–9 Decreased levels of unmet needs were associated with better outcomes in both PLWD and their care partners.7 Case managers in collaboration with primary physicians have a pivotal role in identifying and addressing the needs of the patient–caregiver dyad.4 A systematic review showed that case managers and primary care providers partnership models effectively improved the severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms, as well as caregiver burden, distress, and mastery.10

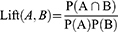

Grouping frequent care needs makes the work of dementia case managers more efficient. A previous report from our dementia collaborative team revealed five care needs as a basic care need bundle when a patient with dementia was first diagnosed, including appropriate scheduling of activities, regular outpatient follow-up treatment, introduction and referral of social resources, referral to family support groups and care skills training, and health education for dementia and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD).11 More than 40% of PLWD and their caregivers needed care involved in the basic bundle. In male patients with vascular cognitive impairment, care for the mood of the caregiver was the sixth care need which should be addressed in addition to the basic care need bundle.12 To further help elementary case managers make an appropriate regular assessment, our case manager-based dementia collaborative team adjusted the unmet needs and defined when and how to use those needs since September 2020, ie, care need 2.0 (Table 1). Our team arranged a face-to-face assessment every 6 months including cognition, function, living status, home environment, and behavior and psychological symptoms of the patient, as well as the stress, mood, and preference of the caregiver in order to elucidate their unmet needs. Case managers then performed monthly follow-up by phone to check if the unmet needs were satisfied.

|

Table 1 Care Needs Addressed by Changhua Christian Hospital |

Multiple chronic diseases increased the risk of dementia in older adult; therefore, PLWD were always accompanied with multimorbidity.13 Eighty-three percent of PLWD had two or more chronic comorbid conditions, which increased the care load and complicated caregivers’ transition experiences.14,15 PLWD with multiple chronic conditions had a more rapid progression and worse outcomes than those with fewer conditions.16 PLWD with co-occurring chronic conditions also negatively impacted hospitalization, emergency department visit, mortality, institutionalization, and functional outcomes.17,18 Caregivers usually experienced worse health conditions, decreased social life, and higher responsibility while taking care of PLWD with multiple chronic conditions.15 Successful strategies in caring for PLWD and their caregivers would rely on not only clinical treatments but also evaluation of the whole-person including addressing the combination of dementia and multimorbidity.19 No literatures have been found to focus on the care needs of caregivers and PLWD with multiple chronic diseases. The aim of the present study was to find the combination of care needs in PWLD with multiple chronic diseases and their care partners.

Patients and Methods

Patients who were diagnosed with dementia at the memory clinic of Changhua Christian Hospital and used care need 2.0 from September 2020 to July 2021 were enrolled in this study. The diagnosis of dementia for each patient was based on clinical dementia rating (CDR) scale by a clinical psychologist.20 The clinical trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Changhua Christian Hospital (CCH IRB 160615). The need for informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Changhua Christian Hospital because this study used a retrospective study design. All data were recorded in the electronic medical chart with the highest confidentiality and compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Initially, there were 176 patients who used care need 2.0 as shown in Table 1 but only 83 patients who had multiple chronic diseases. In this study, when a patient had two or more chronic diseases from a list of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, anemia, and hearing impairment, then the patient had multiple chronic diseases.

Variables such as age, gender, and the severity of clinical dementia rating for each patient were summarized in Table 2. In addition, the follow-up information for patients including feeding, hypnotics, mobility, getting lost, mood symptoms, and behavioral and psychological symptoms are provided in Table 3. Nearly 60% of the patients were aged 75–84 years, and the percentage of female patients were slightly higher than that of male patients. Hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and hearing impairment were the top four chronic diseases among the patients. Moreover, nearly 50% of the patients had a very mild dementia. On the other hand, the majority of the patients could feed independently (89.2%), did not need to use hypnotics (75.9%), could walk independently (56.6%), and did not get lost (60.2%). The highest frequency in mood symptoms was anger (22.9%) followed by dysthymia (15.7%), depression (14.5%), and emotional liability (14.5%). Finally, the highest frequency in behavioral and psychological symptoms was delusion (22.9%) followed by hallucination (14.5%). It is worth to note that the presence of BPSD was evaluated by psychologists or trained nursing case managers, and most of the BPSD listed in the neuropsychiatric inventory were recorded. Other abnormal behaviors frequently observed in dementia patients such as wandering, pathological crying or laughing, cursing others, akathisia, and akinesia were noted by trained nursing case managers. The frequencies of 26 care needs used among 83 dementia patients with multiple chronic diseases are summarized in Table 4, where social resources referral and legal support (Care 1), disease knowledge education (Care 2), care for the mood of the caregiver (Care 11), memory problem care (Care 5), fall prevention (Care 8), and adjusting home environment safety (Care 9) were the care needs with top 6 frequencies. In the present study, only 18 of 26 care needs were used due to a smaller sample of size for dementia patients with multiple chronic diseases.

|

Table 2 Demographic Variables of Dementia Patients with Multiple Chronic Diseases |

|

Table 3 Follow-Up Variables of Dementia Patients with Multiple Chronic Diseases |

|

Table 4 Frequencies of 26 Care Needs Used Among 83 Dementia Patients with Multiple Chronic Diseases |

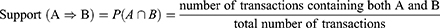

The purpose of this study was to find the care need combinations for PLWD with multiple chronic diseases. Studies such as Jhang et al11,12 showed that the Apriori algorithm was an effective approach to identify care need bundles for PLWD by revealing statistical correlation through setting up support, confidence, and lift. Therefore, this study employed the Apriori algorithm to find care need bundles for PLWD with multiple chronic diseases. The support, confidence, and lift are defined below.21–24 The support of an association rule A ⇒ B calculates the percentage of transactions containing both A and B in the database depicted in Equation (1):

The confidence of the association rule A ⇒ B evaluates the accuracy of the rule by computing the percentage of transactions containing A and also containing B simultaneously in the database depicted in Equation (2):

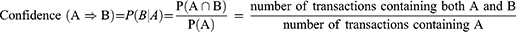

Lift measures if the correlation of A and B is to be independent or dependent depicted in Equation (3). If a lift is equal to 1, A and B are independent and no rule will be generated containing either event. If a lift is greater than 1, A and B are positively dependent.

The Apriori algorithm in IBM SPSS Modeler 14.1 was applied. Data type for each variable was defined by the numerical values as shown in Tables 2 and 3. In addition, each care need used a two-point scale. If a care need was applied, a value of 1 was assigned. If not, a value of 0 was given. This study had twofold. The first stage was to find care need combinations. Therefore, 26 care needs were the input variables for both antecedents and consequents. In the second stage, the purpose was to find care need combinations along with the associations of variables listed in Tables 2 and 3. Specifically, the input variables for antecedents included age, gender, and CDR from Table 2 and feeding, hypnotics, mobility, getting lost, 10 types of mood symptoms, and 15 types of behavioral and psychological symptoms from Table 3. Moreover, 26 care needs were the input variables for both antecedents and consequents. The minimum support, confidence, and lift values based on the suggestions from Jhang et al11,12 were set to 10%, 90%, and greater than 1, respectively.

Results

In the first stage, there were six rules generated as shown in Table 5. Memory problem care (Care (5)) was associated with social resources referral and legal support (Care (1)). In addition, fall prevention (Care (8)) was associated with Care (1). The higher support value indicated the more frequent the care need combinations were from the database. Thus, Care (1), Care (3), Care (5), and Care (8) could be bundled together to form a basic care need combination for dementia patients with multiple chronic diseases when support was set to greater than 19%. In addition to these four care needs, disease knowledge education (Care (2)) and hypertension care (Care (16)) could be implemented to provide a more comprehensive combination if needed.

|

Table 5 Six Rules in the First Stage of the Study |

In the second stage, there were 80 rules generated with the support values ranging from 10% to less than 40%. In order to show the rules in a practical viewpoint, these rules were classified into three groups, namely 30% to less than 40%, 20% to less than 30%, and 10% to less than 20%. For each group, general rules were summarized based on the similarities of rules. In Table 6, there were three rules which could be further summarized into two general rules with 30% to less than 40%. The first general rule indicated that a patient with very mild dementia who did not use hypnotics would require social resources referral and legal support (Care (1)) regardless if the patient’s feeding was independent. The second general rule containing only one rule showed that a patient who did not use hypnotics but required disease knowledge education (Care (2)) needed Care (1).

|

Table 6 Two General Rules with Support of 30% but Less Than 40% |

Table 7 summarizes 10 rules which were categorized into 6 general rules with the support of 20% but less than 30%. To further explain the meanings of these general rules, the second and third general rules consisting of four and two rules, respectively, were illustrated. The second general rule showed that a patient who could get lost would require social resources referral and legal support (Care (1)) no matter whether the patient could feed independently, did not use hypnotics, or both. The third general rule indicated that a male patient with very mild dementia who did not use hypnotics would need Care (1) regardless if the patient’s feeding was independent.

|

Table 7 Six General Rules with Support of 20% but Less Than 30% |

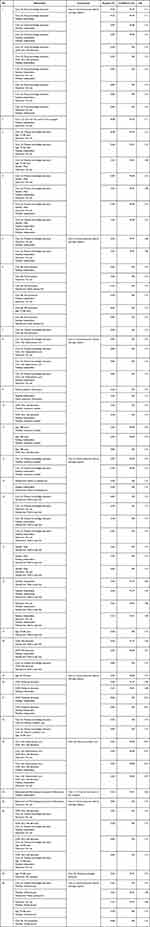

Eighty rules with the support value of 10% but less than 20% were further summarized into 28 general rules as shown in Table 8. The lower support value indicated the less frequent in the database. However, these rules were still important for certain groups because of high confidence values. In fact, more demographic variables were appeared in general rules. For instance, the term “65–74 years old” was found in general rule 19. That is, if a patient whose age was 65–74 years, the patient needed social resources referral and legal support (Care (1)). By the same token, “75–84 years old” was found in general rules 3, 6, 17, 22, 26, 27, and 28. For instance, if a patient whose age was 75–84 years had a fair response for hypnotics, this patient needed disease knowledge education (Care (2)) based on 27th general rule. For the patient whose age was ≥85 years, Care (1) would be needed when the patient needed assistance in mobility regardless of feeding independently or had very mild dementia. For 23rd general rule, when the patient with very mild dementia who needed hypertension care (Care (16)) would require memory problem care (Care (5)) regardless of hypnotics, feeding, or both. It is worth to note that 24th general rule had care for the mood of the caregiver (Care (11)), which was not included in the basic care need combinations. This rule depicted that a patient would require Care (11) when hallucination and feeding independently were incurred simultaneously for the patient.

|

Table 8 28 General Rules with Support of 10% but Less Than 20% |

Setting a lower support value enabled the dementia collaborative care team members to find more rules containing more care needs as well as variables such as age, gender, and the severity of dementia. In doing so, care team members could be easily to identify what care need combinations should be provided for a particular dementia patient. In contrast, rules with higher support values indicated that more PLWD with multiple chronic diseases would need care need bundles. In fact, there would be a trade-off between a higher or lower support value. In our study, if the support value was reduced from 10% to 5% with the confidence of 90% and lift >1, there were 2720 rules available. Obviously, these rules might be complicated in practical uses because several smaller groups of PLWD with multiple chronic diseases might need a wide variety of care needs. These rules might become less valuable for care team members to put into practice.

Discussion

This study found a care need bundle combining four care needs for PLWD with multiple chronic diseases and their caregivers. They were social resources referral and legal support (Care (1)), drug knowledge education (Care (3)), memory problem care (Care (5)), and fall prevention (Care (8)). In addition to the basic care need bundles, disease knowledge education (Care (2)) and hypertension care (Care (16)) were also frequent care needs in PLWD with multiple chronic diseases. In patients with dementia and preserved ambulatory function or with the symptom of hallucination, care for the mood of the caregiver (Care (11)) should be considered as a frequent unmet need.

A previous study in Germany found the most frequent unmet need in PLWD was “nursing treatment and care”, in which “mobility limitation/risk of fall” and “daycare and ambulant care” were the two most common needs.8 The second and third common unmet needs were “social counseling and legal support” and “pharmaceutical treatment and care.” Studies in the United States using Johns Hopkins Dementia Care Needs Assessment disclosed memory disorder education, care skills and knowledge of resources, legal issues/concerns, caregiver mental health, and access to informal support were most prevalent unmet needs for care partners of PLWD.7 For community-living PLWD, home/personal safety, general health care, and maintenance of daily activities were the most frequent unmet needs.9 Both groups also demonstrated that “diagnosis of dementia” was a common need in community-residing individuals with dementia.6,8,25 The present study used a scientific method to combine four care needs for both PLWD and their caregivers as a care need bundle. The four domains included frequent care needs listed in previous literatures. On the other hand, “diagnosis of dementia” was not considered as an unmet need because participants in this study have been diagnosed as dementia patients by neurology or psychiatric specialists.

Hypertension care (Care (16)) was a frequent care need in the present study because 78.3% of PLWD with multiple chronic diseases had hypertension. Hypertension was also the most common comorbid in PLWD as well as in a geriatric population with multiple chronic conditions.18,26 Sufficient evidence showed that moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment had no impact on hypertension medication use in PLWD with co-occurring hypertension.17 In mild dementia patients treated with anti-hypertensive medications, the rate of adverse health events was higher compared with the randomized controlled trials of anti-hypertensive medications.27 Appropriate blood pressure goal setting and prevention of medication related side effects were important in PLWD with hypertension.

Compared with our previous reports, the care needs were adjusted from 15 to 26 items by six categories.11,12 Similar care needs in the basic care need bundle for all dementia population and PLWD with multiple chronic diseases included disease education, care skills training, and referral of social resources.11 Fall prevention should be included into a basic care need bundle in patients with vascular dementia as well as with multiple chronic diseases.11

Care for the mood of the caregiver (Care (11)) should be taken into consideration as an unmet need in multimorbidity dementia patients especially for whom had hallucination or had dementia with preserved ambulatory function. Caregivers of PLWD with multiple chronic conditions experienced a high caregiving load, taken on responsibility for managing multiple complex conditions, and felt worse healthy condition.15 Previous studies also found caregiver’s mental health was a frequent unmet needs,7,25 which was also an element included in the basic care need bundle for male patients with vascular cognitive impairment.12 Preserved ambulatory function or neuropsychiatric symptoms were associated with a high caregiving burden.21,26 Our previous report also found caregivers who cared for patients with moderate Alzheimer’s disease experienced severe depression.23 Dementia care team should watch for caregiver’s mental health and provide suitable education or support group to relieving their stress.

Multimorbidity was often accompanied with frailty, polypharmacy, and dementia.28,29 Hung et al30 found that the comprehensive geriatric assessment guided multidisciplinary interventions (including physical therapy, psychotherapy, pharmacist education, and social resources linkage) were effective to improve frail severity, physical function, and depressive and nutritional status in elderly (45% with dementia). Appropriate intervention toward frail status and polypharmacy maybe also a solution to deal with this complex population.

The strength of this study was forming a care need bundle through combining care needs in a specific population through a scientific method. No studies have been found to discuss the unmet needs, especially for PLDW with multimorbidity. Another strength was the precise selection of care needs through a proper evaluation and shared decision-making between care teams and PLWD and their caregivers. Elementary dementia case managers could efficiently catch the care focus by using the result identified by our study.

There were some study limitations in this study. First, only eight chronic diseases were included into analysis. Some of the comorbidities frequently co-occurring in PLWD such as arthritis, heart failure, pulmonary diseases, cancers, and mood disorders were not collected in our database.18 Because of fewer chronic diseases listed into counting, the study participants were supposed to contain at least three kinds of chronic conditions. Second, there was no universal approach to set up support and confidence values in order to generate association rules when applying the Apriori algorithm. In general, a higher confidence value, say 90% or above, is typically recommended when a conditional probability is applied to study the associations of attributes. In contrast to confidence, setting a higher support value would reduce the number of rules that might result in missing some essential rules with low frequencies. Obviously, there is a trade-off between either higher or lower support values. In this study, we displayed the results by using different intervals of support values to balance this condition. Third, the present study did not include caregiver’s characteristics, which may also influence the choice of care needs. Fourth, the study sample was relatively small and may not represent the true needs of the target population. Also, the study only included patients newly diagnosed of dementia, the care needs in the following period may change.

Conclusion

Four basic care need combinations for PLWD with multiple chronic diseases and their caregivers found in this study were social resources referral and legal support (Care (1)), drug knowledge education (Care (3)), memory problem care (Care (5)), and fall prevention (Care (8)). Disease knowledge education (Care (2)) and hypertension care (Care (16)) were also frequent unmet needs in this specific population. Care for the mood of the caregiver (Care (11)) should be considered especially in PLWD with preserved ambulatory function or with the symptom of hallucination. The collaborative care team should pay more attention to those care needs when assessing this specific population.

Data Sharing Statement

According to our hospital’s regulation, individual de-identified data should pass both the Research and Development Committee and Institutional Review Board (IRB). Researchers should write a research proposal and apply a clinical trial for the IRB of our hospital. All data listed in the present manuscript can be obtained through email if both committees agree the application.

Disclosure

Kai-Ming Jhang, Wen-Fu Wang, Yu-Ching Cheng, and Yu-Chen Tung are co-first authors for this study. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–2734. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6

2. Statistical yearbook of interior; 2018. Available from: https://www.moi.gov.tw/stat/news_detail.aspx?sn=13742.

3. Sun Y, Lee HJ, Yang SC, et al. A nationwide survey of mild cognitive impairment and dementia, including very mild dementia, in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100303. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100303

4. Khanassov V, Vedel I. Family physician-case manager collaboration and needs of patients with dementia and their caregivers: a systematic mixed studies review. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):166–177. doi:10.1370/afm.1898

5. Molony SL, Kolanowski A, Van Haitsma K, et al. Person-centered assessment and care planning. Gerontologist. 2018;58(suppl_1):S32–S47. doi:10.1093/geront/gnx173

6. Black BS, Johnston D, Rabins PV, et al. Unmet needs of community-residing persons with dementia and their informal caregivers: findings from the maximizing independence at home study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(12):2087–2095. doi:10.1111/jgs.12549

7. Antonsdottir IM, Leoutsakos JM, Sloan D, et al. The associations between unmet needs with protective factors, risk factors and outcomes among care partners of community-dwelling persons living with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2022;1–9. doi:10.1080/13607863.2022.2046698

8. Eichler T, Thyrian JR, Hertel J, et al. Unmet needs of community dwelling primary care patients with dementia in Germany: prevalence and correlates. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51(3):847–855. doi:10.3233/JAD-150935

9. Black BS, Johnston D, Leoutsakos J, et al. Unmet needs in community-living persons with dementia are common, often non-medical and related to patient and caregiver characteristics. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(11):1643–1654. doi:10.1017/S1041610218002296

10. Frost R, Walters K, Aw S, et al. Effectiveness of different post-diagnostic dementia care models delivered by primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(695):e434–e441. doi:10.3399/bjgp20X710165

11. Jhang KM, Chang MC, Lo TZ, et al. Using the Apriori algorithm to classify the care needs of patients with different types of dementia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:1899–1912. doi:10.2147/PPA.S223816

12. Jhang KM, Wang WF, Chang HF, et al. Care needs of community-residing male patients with vascular cognitive impairment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:2613–2621. doi:10.2147/NDT.S277303

13. Grande G, Marengoni A, Vetrano DL, et al. Multimorbidity burden and dementia risk in older adults: the role of inflammation and genetics. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(5):768–776. doi:10.1002/alz.12237

14. Griffith LE, Gruneir A, Fisher K, et al. Patterns of health service use in community living older adults with dementia and comorbid conditions: a population-based retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):177. doi:10.1186/s12877-016-0351-x

15. Lam A, Ploeg J, Carroll SL, et al. Transition experiences of caregivers of older adults with dementia and multiple chronic conditions: an interpretive description study. SAGE Open Nurs. 2020;6:2377960820934290. doi:10.1177/2377960820934290

16. Melis RJ, Marengoni A, Rizzuto D, et al. The influence of multimorbidity on clinical progression of dementia in a population-based cohort. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e84014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084014

17. Snowden MB, Steinman LE, Bryant LL, et al. Dementia and co-occurring chronic conditions: a systematic literature review to identify what is known and where are the gaps in the evidence? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(4):357–371. doi:10.1002/gps.4652

18. Mondor L, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB, et al. Multimorbidity and healthcare utilization among home care clients with dementia in Ontario, Canada: a retrospective analysis of a population-based cohort. PLoS Med. 2017;14(3):e1002249. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002249

19. Quinones AR, Kaye J, Allore HG, et al. An agenda for addressing multimorbidity and racial and ethnic disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2020;35:1533317520960874. doi:10.1177/1533317520960874

20. Morris JC. Clinical dementia rating: a reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(Suppl1):173–6; discussion 177–8. doi:10.1017/S1041610297004870

21. Yan GJ, Wang WF, Jhang KM, et al. Association between patients with dementia and high caregiving burden for caregivers from a medical center in Taiwan. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:55–65. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S187676

22. Jhang KM, Wang WF, Chang HF, et al. Characteristics predicting a high caregiver burden in patients with vascular cognitive impairment: using the Apriori algorithm to delineate the caring scenario. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:1335–1351. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S297204

23. Chen YA, Chang CC, Wang WF, et al. Association between caregivers’ burden and neuropsychiatric symptoms in female patients with Alzheimer’s disease with varying dementia severity. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:929–940. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S298196

24. Chang CC, Wang WF, Li YY, et al. Using the Apriori algorithm to explore caregivers’ depression by the combination of the patients with dementia and their caregivers. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:2953–2963. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S316361

25. Johnston D, Samus QM, Morrison A, et al. Identification of community-residing individuals with dementia and their unmet needs for care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(3):292–298. doi:10.1002/gps.2527

26. Lim E, Gandhi K, Davis J, et al. Prevalence of chronic conditions and multimorbidities in a geographically defined geriatric population with diverse races and ethnicities. J Aging Health. 2018;30(3):421–444. doi:10.1177/0898264316680903

27. Welsh TJ, Gordon AL, Gladman JRF. Treatment of hypertension in people with dementia: a multicenter prospective observational cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(9):1111–1115. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2019.03.036

28. Canaslan K, Bulut EA, Kocyigit SE, et al. Predictivity of the comorbidity indices for geriatric syndromes. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22:440. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-03066-8

29. Koch G, Belli L, Lo Giudice T, et al. Frailty among Alzheimer’s disease patients. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013;12(4):507–511. doi:10.2174/1871527311312040010

30. Hung YY, Wang WF, Chang MC, et al. The effectiveness of an outpatient personalized multidisciplinary intervention model, guided by comprehensive geriatric assessment, for pre-frail and frail elderly. Intl J Gerontol. 2022;16(2):89–94.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.